Abstract

Objective

To analyze the results of different strategies for restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch–anal anastomosis (IPAA) in ulcerative colitis.

Summary Background Data

No commonly accepted criteria exist for choosing between the one-stage or the two-stage procedure (with or without temporary diverting ileostomy) for IPAA. The authors analyzed the outcome of patients principally suitable for either of the two alternative surgical strategies.

Methods

A matched-pair control study was performed, comparing surgical details and the early and late outcome of the one-stage (study group, n = 57) versus the two-stage procedure (control group, n = 114), for IPAA.

Results

No differences were found between the study group and the control group regarding the matching criteria gender, median age at IPAA, systemic corticoid medication, or activity of colitis. Comparing the patients who underwent a one-stage procedure with those who underwent a two-stage procedure, the proportion of patients without complications was significantly higher (P = .0042) and the frequency of late complications was significantly lower (P = .0022) in patients who underwent the one-stage procedure. The percentage of patients with anastomotic strictures was significantly higher in the control group than in the study group (P = .0022). No significant difference was found between the two groups regarding early complications, pouch-related septic complications, pouchitis, median duration of surgery for IPAA, median blood loss, need for transfusion, or median hospital stay.

Conclusions

In patients with ulcerative colitis in whom there is a choice between a one-stage procedure or a two-stage procedure with a defunctioning ileostomy, the one-stage procedure is clearly superior. This finding is of great clinical relevance both for the subjective interests of the patient and from an economic point of view.

Surgical treatment is indicated in a certain number of patients with ulcerative colitis (UC), either as emergency treatment for acute complications or electively for a variety of reasons. 1 Total proctocolectomy with construction of an ileal pouch–anal anastomosis (IPAA) offers the chance of eliminating the underlying disease 2–5 and preserving anal continence. This procedure has, therefore, evolved as the therapy of choice for patients with UC requiring surgical treatment. 6–11

However, the early and late outcomes of IPAA may be compromised by several pouch-related complications, among which pouch-related septic complications (PRSCs) 12–15 and pouchitis 16–19 are most frequent. Hence, there is an ongoing debate on whether the results of IPAA may be influenced by different technical procedures 20–28 and strategies 1,29–31 for IPAA. Of these strategies, the choice between the one-stage or the two-stage procedure for performing IPAA has the most apparent implications for patients and has been the subject of comparative studies in the literature. 31–43 In the two-stage procedure, a defunctioning ileostomy is established to divert the fecal stream until the ileoanal anastomosis and the reservoir are securely healed. 31–33

In our experience, a number of patients are principally suitable for both the one- and the two-stage procedure under certain favorable conditions. However, a clear framework for choosing between the alternatives is lacking in the literature. Therefore, we compared the outcome between the one- and the two-stage procedure in a matched control study of a large series of consecutive patients. This retrospective study followed the hypothesis that patients fulfilling certain conditions allow the choice between the two procedures and might profit from the less extensive one because the outcome is either equal or superior, the duration of the operation and total hospital stay are shorter, and the overall risk of intra- and postoperative complications is equal or lower.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The IPAA procedure was introduced at the Department of Surgery, University of Heidelberg, in 1982 and was performed in 703 patients until December 2000. In the present study, results from the 10-year period from January 1991 to December 2000 were analyzed; during this time, 503 patients underwent IPAA for UC at our hospital. The one-stage procedure for IPAA was introduced at our hospital in 1996 and has been performed in 24.8% of all patients since then. In two patients, Crohn’s disease was unexpectedly diagnosed after surgery; these patients were excluded from the analyses.

Data were entered into a clinical registry at the time of surgery and at each follow-up. The registry was maintained and statistical analysis of the data was performed by a biostatistician. In all patients, activity of colitis was measured by clinical features, using the Colitis Activity Index introduced by Rachmilewitz. 44 Patient demographics, diagnosis and duration of disease, indication for colectomy, and early (within 30 days after surgery) and late complications were documented prospectively.

The surgical procedure was standardized and consisted of abdominal proctocolectomy and complete transanal mucosectomy, which involved leaving a short rectum cuff with a length of 3 to 4 cm. A 15-cm ileal J-pouch was constructed using two 90-mm linear staplers (GIA 90 Premium, U.S. Surgical Corp., Norwalk, CT). The IPAA was hand-sewn with 14 to 18 stitches. During the operation, each of the surgeons explicitly documented the state of the IPAA with regard to blood supply and absence of tension.

The IPAA was performed as a one-stage procedure (without diverting ileostomy) in 64 (12.8%) patients, as a two-stage procedure (with diverting ileostomy) in 297 (59.3%) patients, and as a three-stage procedure (colectomy with closure of the rectum 3–6 months before IPAA) in 78 (15.6%) patients. Sixty-four patients undergoing IPAA had previously been treated with subtotal colectomy in other hospitals.

After IPAA, patients were enrolled in a long-term follow-up program with standard intervals of 3, 6, and 12 months in the first year, once yearly for another 4 years, and then once every 2 years. In addition, patients were asked to return to the outpatient department of our hospital if any pouch-related symptoms developed, independently of the scheduled appointments. Pouchitis was diagnosed according to clinical, histologic, and endoscopic criteria as described previously. 16 PRSCs presented as anastomotic leaks, parapouchal abscesses, and pouch–anal fistulas, as reported in detail in a previous publication. 12

Early and long-term outcomes, together with intraoperative features and duration of hospital stay, were compared in a matched-pair control study between patients in whom IPAA had been performed as a one- versus a two-stage procedure. The patients were individually matched with regard to age (± 5 years), gender, Colitis Activity Index (± 4 points), and systemic corticoid medication (0 mg, 1–40 mg, >40 mg prednisolone equivalent dose).

Data were incomplete in seven patients of the study group; they were therefore excluded from the analysis. At our hospital patients with an imperfect IPAA, those in whom toxic colitis, perforation, or perirectal fistula developed, or those with a Colitis Activity Index greater than 16 points are principally regarded as being unsuitable for the one-stage procedure. These patients were therefore not suitable for the control group either and were excluded from the analysis.

Fifty-seven patients were included in the study group, and 114 patients were included in the matched control group. All patients included in the study group and in the control group were principally suitable for both the one- and the two-stage procedure. The decision to omit ileostomy was made individually by the operating surgeon at the end of the operation. No policy existed regarding the dependency of this decision from the individual surgeon’s level of experience.

Statistical Analysis

The significance of differences in proportions between the study group and the control group was calculated by the chi-square test, if appropriate, or the Fisher exact test. The distribution of quantitative parameters was presented as the median with interquartile range (IQR). Quantitative parameters were compared between the study group and the control group using the Mann-Whitney test. Because the cumulative rate of pouchitis and that of PRSC depended on follow-up after IPAA, the distributions of pouchitis and of PRSC were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method. 45 The study group and the control group were matched in a 1:2 relation with the intent of minimizing the chance of selection bias in the control group caused by disregarded parameters. Differences between the study group and the control group were evaluated by the log-rank test. P < .05 was considered as indicating statistical significance. Analyses were performed with SAS software (Release 8.01, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

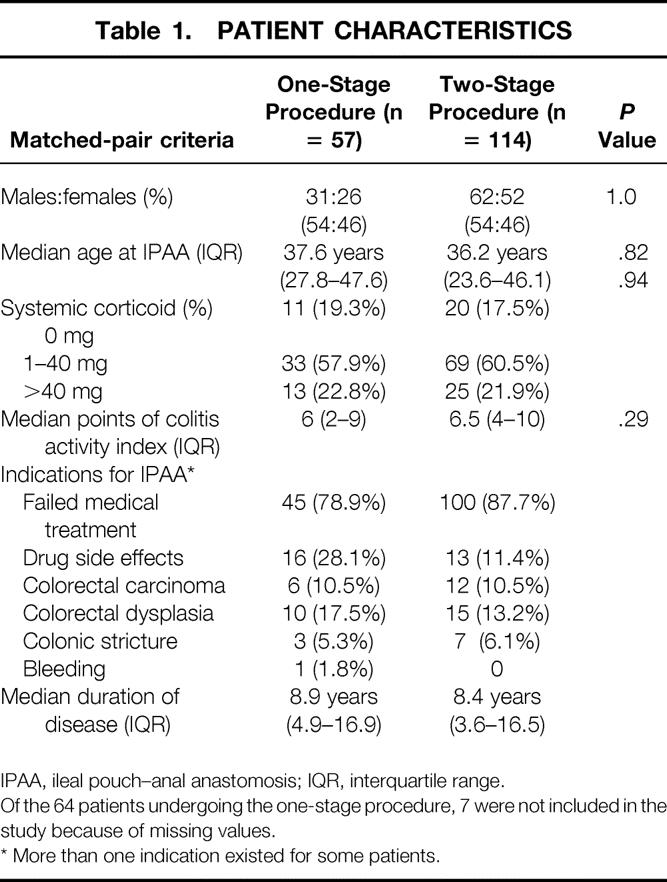

Failed medical treatment was the predominant indication for IPAA in the study group and in the control group, followed by oncologic indications, drug side effects, and colonic stricture. Median duration of UC was 8.9 years (4.9–16.9) in the study group and 8.4 years (3.6–16.5) in the control group (Table 1).

Table 1. PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS

IPAA, ileal pouch–anal anastomosis; IQR, interquartile range.

Of the 64 patients undergoing the one-stage procedure, 7 were not included in the study because of missing values.

* More than one indication existed for some patients.

Each of the patients in the study group (one-stage procedure) was matched with two patients in the control group (two-stage procedure) (n = 57 vs. n = 114). No significant differences existed between the study group and the control group concerning the matching criteria gender, median age at IPAA, systemic corticoid medication, or disease activity (P = 1.0, P = .82, P = .94, and P = .29, respectively).

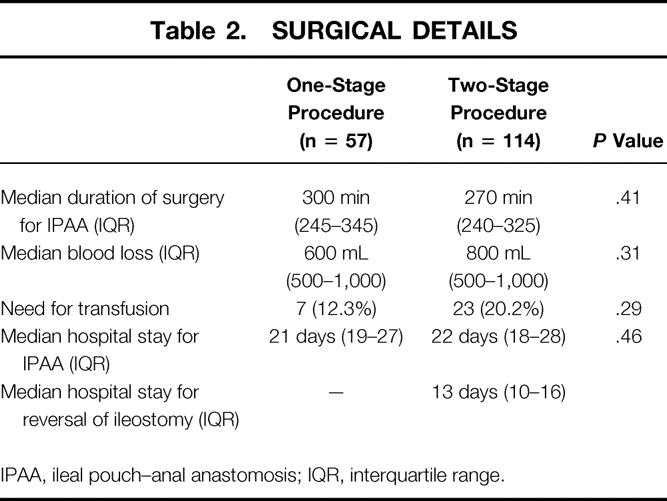

No significant difference existed between the two groups concerning median duration of surgery for IPAA, median blood loss, need for transfusion, or median duration of hospital stay for IPAA (P = .41, P = .31, P = .29, and P = .46, respectively). In the control group, the median duration of hospital stay for reversal of ileostomy was 13 days (10–16) (Table 2).

Table 2. SURGICAL DETAILS

IPAA, ileal pouch–anal anastomosis; IQR, interquartile range.

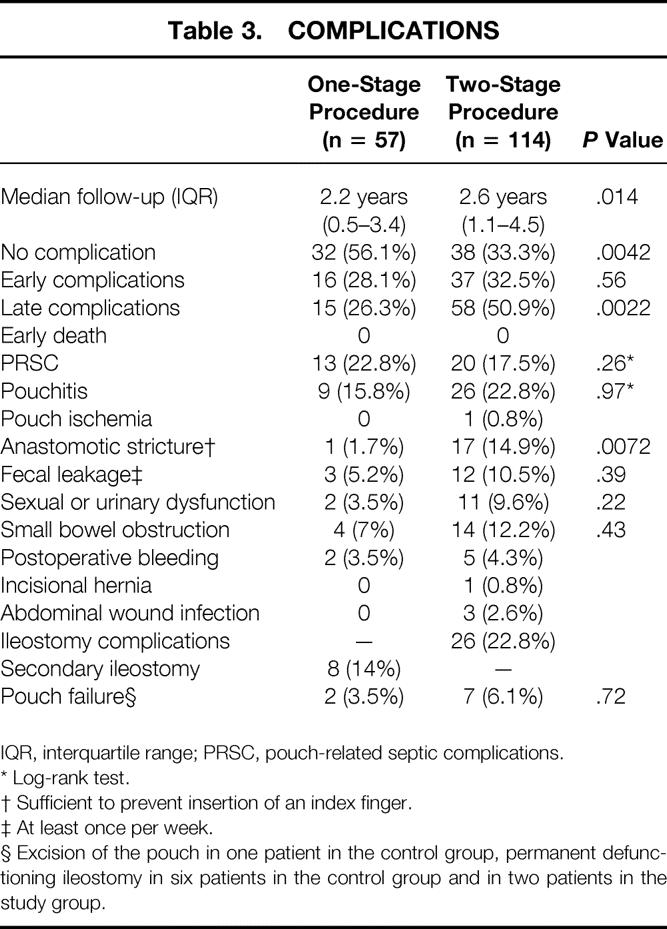

Median duration of follow-up was 2.2 years (IQR 0.5–3.4) in the study group and 2.6 years (IQR 1.1–4.5) in the control group. The percentage of patients without complications was significantly higher in the group who underwent IPAA without ileostomy than in those with ileostomy (56.1% vs. 33.3%, P = .0042) (Table 3). No significant difference between the two groups was found in the occurrence of early complications (P = .56). Late complications were significantly more frequent in the control group than in the study group (P = .0022). The percentage of patients with anastomotic strictures was significantly higher in the control group than in the study group (P = .0072). Fecal leakage, sexual or urinary dysfunction, and small bowel obstruction had a markedly higher frequency in the control group than in the study group, but these differences were not significant (P = .39, P = .22, and P = .43, respectively).

Table 3. COMPLICATIONS

IQR, interquartile range; PRSC, pouch-related septic complications.

* Log-rank test.

† Sufficient to prevent insertion of an index finger.

‡ At least once per week.

§ Excision of the pouch in one patient in the control group, permanent defunctioning ileostomy in six patients in the control group and in two patients in the study group.

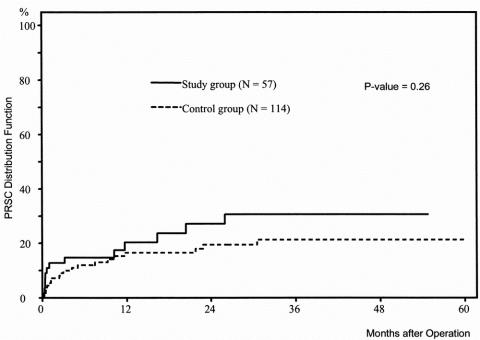

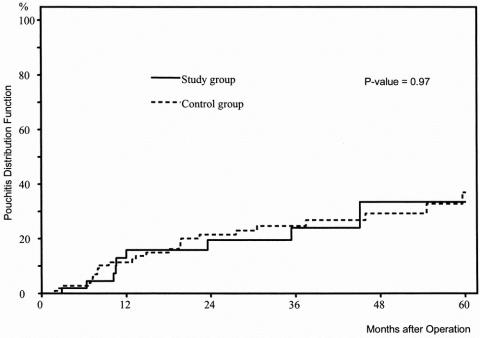

No significant difference was found between the proportion of patients with PRSC (P = .41) or pouchitis (P = .28). As illustrated in the Kaplan-Meier curves (Figs. 1 and 2), the risks of PRSC and pouchitis, respectively, were not significantly different between the study group and the control group (P = .26 and P = .97, respectively). Nevertheless, the Kaplan-Meier curve shows that the increase in the rate of PRSC during the first month of follow-up was higher in patients without ileostomy than in patients with ileostomy.

Figure 1. Distribution function of pouch-related septic complications in 57 patients with ulcerative colitis undergoing ileal pouch–anal anastomosis without ileostomy (study group) versus 114 patients with ulcerative colitis undergoing ileal pouch–anal anastomosis with ileostomy (control group) (Kaplan-Meier estimation).

Figure 2. Distribution function of pouchitis in 57 patients with ulcerative colitis undergoing ileal pouch–anal anastomosis without ileostomy (study group) versus 114 patients with ulcerative colitis undergoing ileal pouch–anal anastomosis with ileostomy (control group) (Kaplan-Meier estimation).

Of the 114 patients in the control group, 12.3% had complications related to reversal of the ileostomy. Secondary ileostomy was performed in eight (14%) of the patients who underwent a one-stage procedure as a result of insufficiency of the IPAA within 30 days after IPAA. In six of these patients, reversal of the secondary ileostomy was possible within 3 months. The frequencies of pouch failure were two (3.5%) and seven (6.1%) in the study and in the control groups, respectively (P = .72). The pouch was excised in one patient in the control group; a permanent defunctioning ileostomy was established in six patients in the control group and in two patients of the study group. No deaths occurred. No cases of peritonitis develop in either group.

DISCUSSION

Restorative proctocolectomy was introduced as the surgical treatment of choice for UC in the early 1980s at several surgical centers, 2–6 and during the first years it was performed almost without exception as a two-stage procedure with a diverting ileostomy. This is presumed to offer the advantage of allowing the IPAA to heal securely without being in contact with the fecal stream. However, studies in the early 1990s yielded the first indications that the outcome after IPAA might, in selected patients, be independent of whether it is performed with protective ileostomy. 33,36,38,42 However, conclusions from these studies are limited because the data were collected retrospectively or because there was considerable inhomogeneity concerning underlying diseases of the patients included in the studies, the pouch design, or the technique for IPAA. The strength of our study lies in the fact that it was performed as a matched-pair analysis, only patients with UC were included, the ileal pouch consistently had a J design, complete mucosectomy was invariably conducted, the IPAA was hand-sewn in all patients, and pre- and postoperative data were collected and documented prospectively. The incidence of PRSC and the incidence of pouchitis were time-dependent during follow-up after IPAA. 12,16 The cumulative risk of these two complications was, therefore, estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method.

Establishment of an ileostomy in IPAA is considered to reduce the incidence and consequences of septic anastomotic complications. 31 It is therefore interesting that no significant difference was observed between patients with ileostomy and patients without ileostomy in terms of both the risk of PRSC, as analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier method, and the consequences of PRSC, such as permanent defunctioning or excision of the pouch. Further, no case of peritonitis occurred in either group of patients. These consequences of PRSC are presumably prevented by our strategy of performing a secondary ileostomy in the early postoperative period as soon as symptoms suspicious of anastomotic insufficiency develop. Despite this aggressive strategy, the rate of secondary ileostomies at our hospital lies within the range reported in the literature. 29,38,40,41 In our experience, patients’ acceptance of this additional surgical measure is high, provided that it has been explained before the beginning of surgical treatment as an implicit risk of IPAA performed primarily as a one-stage procedure.

As in the case of PRSC, the risk of pouchitis was not different between patients with and without ileostomy. The etiology of pouchitis remains unknown. 16,46,47 Our findings suggest that diversion of the fecal stream, which is known to cause diversion colitis, 48,49 does not play a role in the pathogenesis of pouchitis.

The proportion of patients who had no complications was significantly lower in patients receiving IPAA without ileostomy than in those with ileostomy. The occurrence of late complications obviously accounts for this finding, because these are significantly more frequent in patients undergoing the two-stage procedure, whereas no difference was observed in the frequency of early complications between the two groups. The predominantly late complications in the two-stage group were anastomotic strictures, fecal leakage, sexual or urinary dysfunction, and small bowel obstruction. Anastomotic stricture was the only complication developing in a significantly higher proportion of patients in the control group than in the study group. It is conceivable that the passage of the fecal stream accounts for this result, because it begins a few days after IPAA in patients without ileostomy and might have a dilatating effect on the anastomosis, thus preventing the development of strictures.

High doses of systemic corticoid medication have been advocated as a criterion for not omitting ileostomy, 29 and investigations at our hospital showed recently that high corticoid dosage is an independent risk factor for PRSC. 12 However, high doses of systemic corticoid medication were not considered as a strict contraindication for omitting ileostomy in our series of patients by the operating surgeons. It is therefore interesting to see that the establishment of an ileostomy did not prevent the occurrence of PRSC in patients who had been receiving high doses of corticoid medication before surgery.

In deciding whether to perform IPAA with or without ileostomy, the surgeon must take into account operative technical aspects, medical preconditions of the patient, and financial costs. Features of the operative setting, such as duration of surgery or blood loss for IPAA, as well as the length of hospital stay for IPAA, did not differ between the two groups. However, patients treated with IPAA as a two-stage procedure had to undergo another operation for reversal of the ileostomy. In our study, this accounted for another 2 weeks in the hospital, causing an additional risk of perioperative complications, considerable time off work for the patient, and markedly higher overall costs for surgical therapy.

Finally, the choice of the optimal surgical strategy for IPAA must be based on the patient’s subjective preferences. The patient’s choice may be made irrespective of the advantages and disadvantages of omitting ileostomy found in this study.

In conclusion, in patients with UC in whom there is a choice between either a one-stage procedure or a two-stage procedure with a defunctioning ileostomy, the latter has been considered to be a safer procedure in the literature. However, based on our results, the one-stage procedure is clearly superior. This finding is of great clinical relevance both for the subjective interests of the patient and from an economic point of view.

Footnotes

Correspondence: Udo Heuschen, MD, Department of Surgery, University of Heidelberg, Kirschnerstrasse 1, D-69120 Heidelberg, Germany.

E-mail: udo_heuschen@med.uni-heidelberg.de

Accepted for publication April 2001.

References

- 1.Binderow SR, Wexner SD. Current surgical therapy in ulcerative colitis. Dis Colon Rectum 1994; 37: 610–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parks AG, Nicholls RJ. Proctocolectomy without ileostomy for ulcerative colitis. Br Med J 1978; 2: 85–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Utsunomiya J, Iwama T, Imajo M, et al. Total colectomy, mucosal proctectomy, and ileoanal anstomosis. Dis Colon Rectum 1980; 23: 459–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McIntyre PB, Pemberton JH, Wolff BG, et al. Comparing functional results one year and ten years after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for chronic ulcerative colitis. Dis Colon Rectum 1994; 37: 303–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelly KA. Anal sphincter-saving operations for chronic ulerative colitis. Am J Surg 1992; 163: 5–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dozois RR, Kelly KA, Welling DR, et al. Ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: Comparison of results in familial adenomatous polyposis and chronic ulcerative colitis. Ann Surg 1989; 210: 268–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams NS, Marzouk DEMM, Hallan RI, et al. Function after ileal pouch and stapled pouch-anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis. Br J Surg 1989; 76: 1168–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marcello PW, Roberts PL, Schoetz DJ, et al. Veidenheimer MC. Long-term results of the ileoanal pouch procedure. Arch Surg 1993; 128: 500–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Järvinen HJ, Luukkonen P. Experience with restorative proctocolectomy in 201 patients. Ann Chir Gynaecol 1993; 82: 159–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dozois RR, moderator. Symposium: Surgical aspects of familial adenomatous polyposis. Int J Colorect Dis 1988; 3:1–16. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Meagher AP, Farouk R, Dozois RR, et al. J ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for chronic ulcerative colitis: Complications and long-term outcome in 1310 patients. Br J Surg 1998; 85: 800–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heuschen UA, Hinz U, Allemeyer EH, et al. Risk factors for ileoanal J-pouch-related septic complications in ulcerative colitis and familial adenomatous polyposis. Ann Surg 2001 (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Reissman P, Teoh TA, Weiss EG, et al. Functional outcome of the double stapled ileoanal reservoir in patients more than 60 years of age. Am Surg 1996; 62: 178–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mikkola K, Luukkonen P, Järvinen HJ. Long-term results of restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis. Int J Colorect Dis 1995; 10: 10–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tan HAT, Connolly AB, Morton D, et al. Results of restorative proctocolectomy in the elderly. Int J Colorect Dis 1997; 12: 319–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heuschen UA, Autschbach F, Allemeyer EH, et al. Long-term follow-up after ileo-anal pouch procedure: Algorithm for diagnosis, classification and management of pouchitis. Dis Colon Rectum 2001; 44: 487–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sandborn WJ. Pouchitis following ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: definition, pathogenesis, and treatment. Gastroenterology 1994; 107: 1856–1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ, Batts KP, et al. Pouchitis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: a pouchitis disease activity index. Mayo Clin Proc 1994; 69: 409–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kühbacher T, Schreiber S, Runkel N. Pouchitis: pathophysiology and treatment. Int J Colorect Dis 1998; 13: 196–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gozzetti G, Poggioli G, Marchetti F, et al. Functional outcome in handsewn versus stapled ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Am J Surg 1994; 168: 325–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gemlo BT, Belmonte C, Wiltz O, et al. Functional assessment of ileal pouch-anal anastomosis techniques. Am J Surg 1995; 169: 137–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tuckson WB, Lavery IC, Fazio VW, et al. Manometric and functional comparison of ileal pouch anal anastomosis with and without anal manipulation. Am J Surg 1991; 161: 90–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scotte M, Del Gallo G, Steinmetz L, et al. Ileoanal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis: Results of an evolutionary surgical procedure. Hepato-Gastroenterology 1998; 45: 2123–2125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gullberg K, Liljeqvist L. Gains and losses with stapling an omission of loop ileostomy in pelvic pouch surgery: A matched control study. Int J Colorect Dis 1999; 14: 255–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reilly WT, Pemberton JH, Wolff BG, et al. Randomized prospective trial comparing ileal pouch-anal anastomosis performed by excising the anal mucosa to ileal pouch-anal anastomosis performed by preserving the anal mucosa. Ann Surg 1997; 225: 666–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slors JFM, Ponson AE, Taat CW, et al. Risk of residual rectal mucosa after proctocolectomy and ileal pouch-anal reconstruction with the double-stapling technique. Postoperative follow-up study. Dis Colon Rectum 1995; 38: 207–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seow-Choen F, Tsunoda A, Nicholls RJ. Prospective randomized trial comparing anal function after hand-sewn ileoanal anastomosis without mucosectomy in restorative proctocolectomy. Br J Surg 1991; 78: 430–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luukkonen P, Järvinen H. Stapled vs. hand-sutured ileoanal anastomosis in restorative proctocolectomy. A prospective, randomized study. Arch Surg 1993; 128: 437–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fazio VW, Ziv Y, Church JM, et al. Ileal pouch-anal anastomoses: Complications and function in 1005 Patients. Ann Surg 1995; 222: 120–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hawley PR. Emergency surgery for ulcerative colitis. World J Surg 1988; 12: 169–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williamson MER, Lewis WG, Sagar PM, et al. One-stage restorative proctocolectomy without temporary ileostomy for ulcerative colitis. Dis Colon Rectum 1997; 40: 1019–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sugermann HJ, Newsome HH, Decosta G, et al. Stapled ileoanal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis and familial polyposis without a temporary diverting ileostomy. Ann Surg 1991; 213: 606–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Senapati A, Nicholls RJ, Ritchie JK, et al. Temporary loop ileostomy for restorative proctocolectomy. Br J Surg 1993; 80: 628–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tjandra JJ, Fazio VW, Church JM, et al. Similar functional results after restorative proctocolectomy in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis and mucosal ulcerative colitis. Am J Surg 1993; 165: 322–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gullberg K, Liljeqvist L. Gains and losses with stapling and omission of loop ileostomy in pelvic pouch surgery: a matched control study. Int J Colorect Dis 1999; 14: 255–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matikainen M, Santavirta J, Hiltunen K-M. Ileoanal anastomosis without covering ileostomy. Dis Colon Rectum 1990; 33: 384–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Winslet MC, Barsoum G, Pringle W, et al. Loop ileostomy after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis—Is it necessary? Dis Colon Rectum 1991; 34: 267–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sagar PM, Lewis W, Holdsworth PJ, et al. One-stage restorative proctocolectomy without temporary defunctioning ileostomy. Dis Colon Rectum 1992; 35: 582–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Järvinen HJ, Luukkonen P. Comparison of restorative proctocolectomy with and without covering ileostomy in ulcerative colitis. Br J Surg 1991; 78: 199–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mowschenson PM, Critchlow JF, Peppercorn MA. Ileoanal pouch operation. Long-term outcome with or without diverting ileostomy. Arch Surg 2000; 135: 463–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sugerman HJ, Newscome HH. Stapled ileoanal anastomosis without temporary ileostomy. Am J Surg 1994; 167: 58–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tjandra JJ, Fazio VW, Milsom JW, et al. Omission of temporary diversion in restorative proctocolectomy—is it safe? Dis Colon Rectum 1993; 36: 1007–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cohen Z, McLeod RS, Stephen W, et al. Continuing evolution of the pelvic pouch procedure. Ann Surg 1992; 216: 506–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rachmilewitz D. Coated mesalazine (5-aminosalicylic acid) versus sulphasalazine for the treatment of active ulcerative colitis: A randomized trial. Br Med J 1989; 298: 82–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc 1958; 53: 457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nicholls RJ, Banerjee AK. Pouchitis: risk factors, etiology, and treatment. World J Surg 1998; 22: 347–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schmidt MC, Lazenby AJ, Hendrickson RJ, et al. Preoperative terminal ileal and colonic resection histology predicts risk of pouchitis in patients after ileoanal pull-through procedure. Ann Surg 1998; 227: 654–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Glotzer DJ, Glick ME, Goldman H. Proctitis and colitis following diversion of faecal stream. Gastroenterology 1981; 80: 438–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Orsay CP, Kim DO, Pearl RK, et al. Diversion colitis in patients scheduled for colostomy closure. Dis Colon Rectum 1993; 36: 366–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]