Abstract

Objective

To assess the clinical, endoscopic, and functional results in a group of patients with Barrett’s esophagus undergoing classic antireflux surgery in whom dysplasia and adenocarcinoma were found at a late objective follow-up.

Summary Background Data

There have been isolated reports of patients with Barrett’s esophagus undergoing antireflux surgery who show dysplasia or even adenocarcinoma on follow-up.

Methods

Of 161 patients undergoing surgery, dysplasia developed in 17 (10.5%) at late follow-up and adenocarcinoma developed in 4 (2.5%). These 21 patients represent the group assessed and were compared with 126 surgical patients with long-segment Barrett’s in whom dysplasia did not develop. They were evaluated by clinical questionnaire, multiple endoscopic procedures and biopsy specimens, 24-hour pH studies, and 24-hour bilirubin monitoring.

Results

Of the 17 patients with dysplasia, 3 were asymptomatic at the time that dysplastic changes appeared; all patients with adenocarcinoma had symptoms. Two patients (12%) in the dysplasia group had short-segment Barrett’s; all patients with adenocarcinoma had long-segment Barrett’s. Manometric studies revealed an incompetent lower esophageal sphincter in 70% of the dysplasia group, similar to nondysplasia patients with recurrence, and in 100% of the adenocarcinoma group. The 24-hour pH study showed pathologic acid reflux in 94% of the patients with dysplasia, similar to patients with recurrence without dysplasia, whereas bilirubin monitoring showed duodenal abnormal reflux in 86% of the patients. Among patients with dysplasia, three different histologic patterns were identified. All patients with adenocarcinoma had initially intestinal metaplasia, with appearance of this tumor 6 to 8 years after surgery.

Conclusions

Patients with Barrett’s esophagus who undergo antireflux surgery need close and long-term endoscopic and histologic surveillance because dysplasia or even adenocarcinoma can appear at late follow-up. Metaplastic changes from fundic to cardiac mucosa and then to intestinal metaplasia and later to dysplasia or adenocarcinoma can clearly be documented. There were no significant differences in terms of clinical, endoscopic, manometric, 24-hour pH, and bilirubin monitoring studies between patients with recurrence of symptoms without dysplastic changes, and patients with dysplasia. Therefore, the high-risk group for the development of dysplasia is mainly the group with failed antireflux surgery.

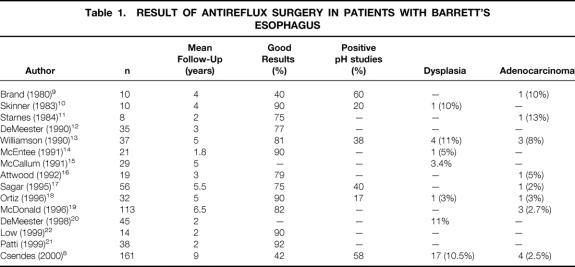

Classic antireflux surgery is highly effective in patients with pathologic gastroesophageal reflux. 1–6 However, among patients with Barrett’s esophagus, these results are not so effective, and based on the length of follow-up, the recurrence rate of symptoms and complications can increase. We recently documented in two studies a high recurrence rate (60%) at a follow-up of almost 10 years; at 2 years this figure had been only 10%. 7,8 The main concern in patients with Barrett’s esophagus (defined as having intestinal metaplasia at the distal esophagus) is the eventual appearance of dysplastic changes and finally adenocarcinoma. In addition to our data, other such patients have been described in the population of patients with Barrett’s undergoing antireflux surgery (Table 1). 9–22 The purpose of the present prospective study was to determine the incidence, the clinical and functional results, and the results of histologic studies in a group of patients with Barrett’s undergoing classic antireflux surgery and in whom dysplasia or adenocarcinoma appeared at late follow-up, compared with similar patients in whom no dysplasia appeared at late follow-up.

Table 1. RESULT OF ANTIREFLUX SURGERY IN PATIENTS WITH BARRETT’S ESOPHAGUS

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

This prospective study, which started in March 1978 and ended in December 1992, included 161 patients with Barrett’s esophagus who underwent classic antireflux surgery. Follow-up ended in December 1999. At late follow-up, dysplasia had developed in 17 patients (10.5%) in the specialized columnar epithelium lining the distal esophagus, and adenocarcinoma had developed in 4 patients (2.5%) in the distal esophagus. These 21 patients represent the group under study in the current assessment and were compared with the 126 patients who underwent the same antireflux surgery but in whom no dysplasia or adenocarcinoma had appeared at late follow-up. The other 14 patients not included in this study comprised 1 patient who died after surgery and 13 (8.1%) lost to follow-up. Patients with dysplasia or adenocarcinoma at the time of initial surgery were not included. To be included in this study, patients had to have several biopsy specimens taken distal to the squamocolumnar junction that excluded the presence of dysplasia at the time of the initial antireflux surgery. All of these patients had more than 3 cm of the distal esophagus lined by columnar epithelium. This study started in 1978, and the concept of Barrett’s at that time included the presence of columnar-lined distal esophagus. Therefore, of the 161 patients, 5 had fundic mucosa and 8 had cardiac mucosa lining the distal esophagus. Given the present concept of Barrett’s, only 148 patients (92%) had intestinal metaplasia before initial surgery.

Clinical Assessment

A careful clinical assessment was performed in each patient before surgery, asking about the presence of typical gastroesophageal reflux symptoms. They were graded on a scale from 1 to 3 according to previously described criteria. 23 For the late clinical evaluation, a modified Visick gradation was used:24 Visick I, no symptoms; Visick II, mild or episodic symptoms, easily controlled by medical treatment or diet adjustment with no need for permanent medication; Visick III, frequent, daily symptoms requiring permanent medical treatment and frequent medical consultations; Visick IV, failure of surgery, with recurrence of reflux symptoms or severe symptoms requiring reoperation. Clinical recurrence was considered to be present when Visick grade III or IV was present at late follow-up.

Endoscopic Examination

Most of the endoscopic procedures were performed by two of the authors (A.C., I.B.), using an Olympus GIF XQ-20 endoscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Special care was taken to measure the exact location of the squamocolumnar junction at the beginning and end of the procedure, avoiding the “push and pull” effect of the endoscope. 25 The presence of an esophageal peptic ulcer was carefully determined 26,27 and the location and size of the ulcer were also measured. In case of a stricture, its internal diameter and length were also determined. In addition, several consecutive biopsy samples were taken distal to the squamocolumnar junction to determine the type of epithelium lining the distal esophagus (fundic, cardiac, or specialized epithelium with intestinal metaplasia). This procedure was performed in all patients before and several times after surgery. Endoscopic recurrence was defined when erosive esophagitis or active peptic ulcer was present at late follow-up.

Histologic Analysis

Four biopsy specimens were taken 5 mm distal to the squamocolumnar junction. Then, according to the endoscopic length of the Barrett’s, four biopsy samples, each 2 cm distally, were taken at each endoscopic procedure. They were immediately submerged in a 10% formalin solution and sent for histologic examination. They were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and Alcian blue stain at pH 2.5. The type of epithelium lining the distal esophagus was carefully determined, including the presence of intestinal metaplasia. Fundic mucosa was identified by the presence of parietal and chief cells at the deep glandular layer. Cardiac mucosa was identified by the presence of mucous-secreting columnar cells. Specialized intestinal metaplasia was defined by the presence of well-defined goblet cells, confirmed by positive staining with Alcian blue at pH 2.5.

The finding of dysplasia at the specialized columnar epithelium was classified in accordance with previous reports. 28,29 It was considered low grade if the nuclear cytoplasmic ratio was slightly increased with stratification of the underlining epithelium, with loss of polarities and mitotic figures with an increased nuclear cytoplasmic ratio. It was considered high grade if the above abnormalities were markedly present, with the addition of architectural changes such as glandular crowding and proliferation. Our protocol established that if any typical dysplastic change appeared, biopsy specimens were repeated 2 weeks later; only if the same changes appeared again was the patient was defined as having dysplasia.

Manometric Evaluation

Manometry was carried out after 12 hours of fasting with patients in the supine position; details have been published. 26,27 All values were expressed in mm Hg. Three manometric characteristics of the lower esophageal sphincter were determined: resting pressure, total length, and abdominal length. This latter measurement was taken from the distal end of the sphincter up to the respiratory inversion point, the level at which the end-expiratory pressure changes from a positive to a negative deflection. 23,30 In each patient three slow pull-throughs were obtained; therefore, the mean values were taken from 12 determinations per patient. The presence of a mechanically incompetent sphincter was defined if one of the following parameters was present: lower esophageal sphincter pressure 6 mm Hg or less, total length less than 20 mm, and abdominal length less than 10 mm. 30 The amplitude of the distal esophageal contractile waves was also determined.

Intraesophageal pH Study

The 24-hour intraesophageal pH test was performed after 12 hours of fasting. 31,32 The catheter was introduced through the nose into the stomach (Digitrapper, Synectics, Stockholm, Sweden) and was then placed 5 cm above the manometric upper border of the lower esophageal sphincter (manometry was always performed before this procedure). From the six different parameters that could be evaluated, the most useful and practical was the percentage of time during which the intraesophageal pH was less than 4 (normal: <4% per 24 hours [55 minutes]).

Monitoring of Esophageal Exposure to Duodenal Juice

This 24-hour monitoring procedure has been developed to measure spectrophotometrically the intraluminal bilirubin concentration. 33,34 It involves a portable opticoelectronic data logger (Bilitec 2000, Synectics) connected to a fiberoptic probe that is passed transnasally and positioned 5 cm proximal to the lower esophageal sphincter. This sensor is 3 mm in diameter and 140 cm long and contains 30 plastic optical fibers bonded together. The tip of the probe contains a 2-mm space for sampling. The light source is provided by two light-emitting diodes that emit a 460-nm signal light (blue spectrum) and a 565-nm reference light (green spectrum). They are stimulated alternately for a duration of 0.5 seconds. The specific wavelength of absorption for bilirubin is 453 nm, and this is highly reproducible despite pH changes produced by environment or food intake. It allows more than 5,400 measurements to be made during 24 hours. The final calculation is based on the percentage of time that bilirubin is measured in the esophagus with an absorbance of more than 0.2 (normal value: <2% [28 minutes]).

Statistical Analysis

For statistical evaluation we used the Fisher exact test, the chi-square test, and the Mann-Whitney test, with P < .05 as significant.

Surgical Procedure

Patients underwent classic posterior gastropexy and calibration of the cardia (130 patients) as described previously 35–38 or Nissen 360° fundoplication (31 patients), associated with highly selective vagotomy in all.

RESULTS

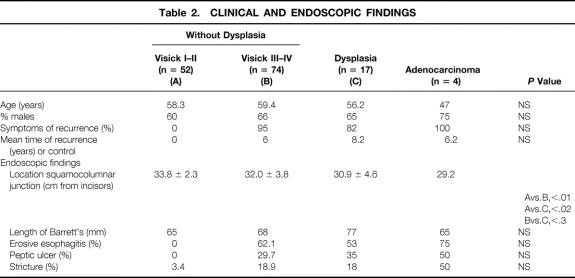

The main clinical and endoscopic findings at the time of appearance of dysplasia or adenocarcinoma compared with patients without dysplasia are shown in Table 2. Patients without dysplasia are separated into two categories (Visick grade I and II vs. grade III and IV) based on late follow-up at a mean of 6 years after surgery. Because of the small number of patients with adenocarcinoma (n = 4), they were not included for statistical evaluation. Fifty-two patients were asymptomatic in Visick grade I or II (41.2%); 74 patients had recurrence of symptoms (58.8%) with Visick grade III or IV. There was no significant difference between the groups undergoing the two different surgical procedures (posterior gastropexy with calibration of the cardia [57% recurrence] or 360° fundoplication [61% recurrence]). In all groups men predominated. In 14 of 17 patients with dysplasia, symptoms of recurrent reflux were present, mainly severe heartburn or regurgitation. However, three patients (18%) had no symptoms and were completely asymptomatic (Visick I). Similarly, 5% of patients with Visick grade III or IV without dysplasia were asymptomatic despite clear endoscopic recurrence. All four patients with adenocarcinoma had reflux symptoms. The mean time for appearance of reflux symptoms after the initial surgery was 6 years for patients without dysplasia, 8 years for patients with dysplasia, and 6 years for patients with adenocarcinoma.

Table 2. CLINICAL AND ENDOSCOPIC FINDINGS

The main endoscopic findings showed that the squamocolumnar junction of patients without dysplasia with Visick grade I or II was significantly more distal than in patients without dysplasia with Visick grade III or IV or patients with dysplasia. The length of Barrett’s was similar in all groups. Peptic ulcer and stricture were present in a similar proportion among patients with Visick grade III or IV with or without dysplasia.

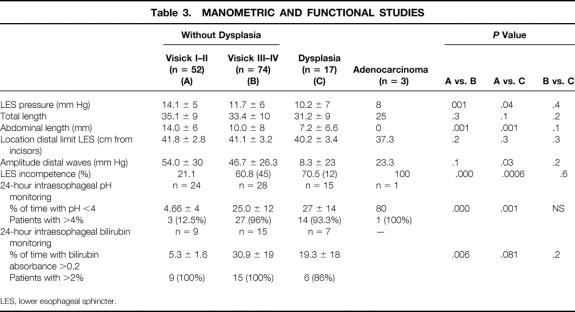

The principal manometric and functional results at the time of appearance of dysplasia or adenocarcinoma are shown in Table 3. Also in this table, patients with adenocarcinoma were not included in the statistical analysis because of the small number of patients evaluated. Patients without dysplasia in Visick grade I or II had significantly different values from patients with recurrence without dysplasia (Visick grade III or IV) or patients with dysplasia with respect to lower esophageal sphincter pressure, abdominal length of the sphincter, percentage of incompetent lower esophageal sphincter, acid reflux, and duodenal reflux into the distal esophagus. In the 24-hour pH studies, only 12.5% of patients with Visick grade I or II had an abnormal value, whereas 96% of patients in Visick grade III or IV without dysplasia, 93% of patients with dysplasia, and the only patient with adenocarcinoma evaluated had abnormal results. Although all patients with Visick grade I or II showed a pathologic duodenoesophageal reflux, the mean value was significantly lower compared with the other groups.

Table 3. MANOMETRIC AND FUNCTIONAL STUDIES

LES, lower esophageal sphincter.

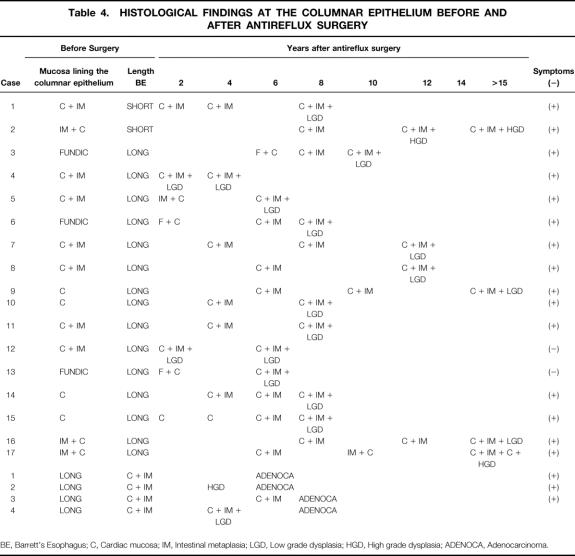

Table 4 shows the main histologic findings, comparing symptoms at the time of recurrence and the length of Barrett’s. In this group, seven patients had two endoscopic and biopsy evaluations after surgery, nine patients had three endoscopic evaluations, and one patient had four endoscopic and biopsy evaluations. Among the patients with dysplasia, two had short-segment specialized columnar epithelium. One of them was asymptomatic at the time of appearance of dysplasia. Among patients with long-segment columnar epithelium, there were two asymptomatic patients. The histologic findings distal to the squamocolumnar junction before the initial antireflux surgery showed three different patterns. Three patients had initially fundic mucosa, but 2 to 6 years later they showed a metaplastic change to cardiac mucosa, then 2 years later they had a second metaplastic change to intestinal metaplasia, and 2 years later they showed low-grade dysplasia (6–10 years after the initial surgery). Four patients had cardiac mucosa at the initial surgery. These patients 4 to 8 years later showed a metaplastic change to intestinal metaplasia; 2 to 4 years later two patients showed low-grade dysplasia and two others presented 5 and 10 years later with low- and high-grade dysplasia. In the third pattern, 10 patients had intestinal metaplasia in cardiac mucosa at the time of the initial surgery. In two of them, low-grade dysplasia developed 2 years after surgery, whereas eight had dysplasia 6 to 20 years after surgery.

Table 4. HISTOLOGICAL FINDINGS AT THE COLUMNAR EPITHELIUM BEFORE AND AFTER ANTIREFLUX SURGERY

BE, Barrett’s Esophagus; C, Cardiac mucosa; IM, Intestinal metaplasia; LGD, Low grade dysplasia; HGD, High grade dysplasia; ADENOCA, Adenocarcinoma.

All four patients with adenocarcinoma initially had intestinal metaplasia with cardiac mucosa. One of them 4 years later developed high-grade dysplasia and 2 years later adenocarcinoma. In the other three patients, carcinoma developed 6 to 8 years after surgery.

DISCUSSION

These results suggest that in some patients with Barrett’s esophagus who undergo antireflux surgery, dysplastic changes and even adenocarcinoma can be seen with late endoscopic and histologic surveillance. These changes can appear even in asymptomatic patients, showing that clinical evaluation alone is not enough; in addition, objective studies should be performed. Patients with dysplasia have similar clinical, endoscopic, and functional behavior compared with patients with Barrett’s who have recurrence of symptoms at late follow-up (Visick grade III or IV) but who do not have dysplasia. We also show the metaplastic changes from fundic mucosa to cardiac mucosa, then to intestinal metaplasia, and later to dysplasia or even adenocarcinoma in sequential studies.

In studies examining patients undergoing surgery for Barrett’s and their late follow-up, we have noticed that most authors combine patients without and with Barrett’s in the same surgical group. We found 15 specific surgical reports concerning the surgical treatment of Barrett’s and eventual regression or appearance of dysplastic changes or adenocarcinoma at late follow-up (see Table 1). Brand et al in 1980 9 described 10 patients with “columnar epithelium” treated with Nissen fundoplication. In four patients, regression to squamous epithelium occurred; in one patient (10%), adenocarcinoma developed 4 years after surgery. Six patients (60%) still had a positive acid reflux test. Skinner et al in 1983 10 reported 13 patients, but only 10 were followed up for 4 years. Of five patients without dysplasia, this histologic change appeared in one. Of another five patients with low-grade dysplasia, it disappeared in two. Twenty percent of patients had a positive acid reflux test. Starnes et al in 1984 11 reported eight patients with long-segment Barrett’s treated by Nissen fundoplication. At 26 months of follow-up, they observed good results in 75% of patients, but adenocarcinoma developed in one patient (13%). Williamson et al in 1990 13 described 37 patients with long-segment “columnar epithelium” (it is not clear how many had intramuscular). At 5 years they found an 81% rate of symptomatic success, but positive pH studies were seen in 38% of the patients. In three patients (8%), adenocarcinoma appeared 1 to 10 years after surgery. All three patients seemed to have had adequate antireflux surgery. McEntee et al in 1991 14 described 21 patients with columnar epithelium who underwent Nissen or Angelchick procedures and who were followed up for 1.8 years. In four patients with low-grade dysplasia, regression occurred. However, in one patient without dysplasia, low-grade dysplasia developed. McCallum et al in 1991 15 reported in an abstract that among 29 patients who underwent Nissen fundoplication and were followed up for 5 years, dysplasia appeared in 3.4%; in contrast, in patients receiving medical treatment only, 20% of patients had low-grade dysplasia. Attwood et al in 1992 16 described 19 patients with long-segment Barrett’s followed up for 3 years. There was a 21% recurrence rate and a 16% complication rate; adenocarcinoma appeared in one patient (5%). Sagar et al in 1995 17 described 56 patients with Barrett’s treated by Nissen fundoplication and followed up for 5.5 years. There was regression of Barrett’s in 24 patients (43%) and progression in 9 patients (16%). Adenocarcinoma developed in one patient (2%). Ortiz et al in 1996 18 compared 32 patients (27 with intramuscular) who underwent Nissen fundoplication with 31 who did not undergo surgery. At 5 years there was a 90% success rate in the surgical group, but 16% had positive 24-hour pH studies. Adenocarcinoma developed in one patient (3%). McDonald et al in 1996 19 reviewed the experience of the Mayo Clinic in 113 patients with Barrett’s. They reported a surgical death rate of 1%, a high incidence of postoperative complications (36%), and a reoperation rate of 4.4%. The follow-up was 6.5 years, with a symptomatic success rate of 81%. However, postoperative endoscopy was performed only once in 64% and not at all in the rest. In the control group, erosive esophagitis was present in 15% and persistent esophageal peptic ulcer in 14%. Radiologic studies could be done in 39 patients and showed hiatal hernia in 23% and reflux in 23%. In three patients, adenocarcinoma developed 1, 2, and 3 years after surgery. DeMeester et al in 1998 19 described 15 patients with intestinal metaplasia of the cardia and 45 patients with Barrett’s who underwent antireflux surgery. Low-grade dysplasia disappeared in one patient with intestinal metaplasia of the cardia (IMC) and in six of nine patients with Barrett’s. However, in 11% of patients, intramuscular progressed to low-grade dysplasia at a mean follow-up of 25 months. Two reports, by DeMeester et al in 1990 12 and Patti et al in 1999, 21 showed neither regression nor progression in their patients with a short follow-up. Finally, Low et al in 1999 22 described 14 patient with long-segment Barrett’s followed up for 25 months after laparoscopic Nissen surgery. They reported a decrease in the results of the 24-hour acid reflux test after surgery, but to values above normal, and regression of low-grade dysplasia in four patients, without progression.

The summary of all these findings is shown in Table 1. As can be seen, of the 15 reports, in 13 the number of operated patients is small (8–56; mean 27), the follow-up is very short (1.5–5 years; mean 3.4), and no objective evaluations are presented, with few manometric data and only five with acid reflux test studies. What is more worrisome for us is the lack of endoscopic and biopsy follow-up. Dysplasia appeared at this short follow-up in seven reports in 3% to 11% of patients, and progression to adenocarcinoma after antireflux surgery was reported in eight reports in 2% to 13% of patients. We believe that these are convincing data showing that antireflux surgery can decrease but not obviate the risk of dysplasia or adenocarcinoma after classic antireflux surgery. In this study, we show that the longer the follow-up, the greater the possibility of such progression.

We compared clinical, endoscopic, and functional studies in three groups of patients undergoing the same antireflux surgery: patients without dysplasia who were asymptomatic (Visick grade I or II) at late follow-up; patients without dysplasia but with clinical or endoscopic recurrence at late follow-up (Visick grade III or IV); and patients in whom dysplasia appeared at late follow-up. To our knowledge, this is the first time that this kind of comparison has been performed. The results have shown that patients with recurrence (Visick grade III and IV) and patients with dysplasia have similar clinical, endoscopic, and functional behavior; the rates of recurrence of symptoms and the rates of endoscopic and functional failures in both groups were very similar. We found no significant differences comparing the surgical procedures (posterior gastropexy with calibration of the cardia or Nissen fundoplication), as we have reported previously. 7,8 Therefore, it is impossible to distinguish early on patients with Barrett’s who will go to develop dysplasia. From a practical point of view, only close endoscopic and biopsy surveillance can detect dysplasia. Therefore, the “high-risk” group for the development of dysplasia is mainly the group with failed antireflux surgery, although 18% of the patients were asymptomatic. We postulate, as we have previously reported, 7,8 that in these patients with Barrett’s, with a long history of symptomatic reflux, with a lower esophageal sphincter with great structural damage and dilatation, and with reflux of acid and duodenal contents into the distal esophagus, it is difficult to recreate a “normal” or physiologic sphincter. Antireflux surgery can work initially for some years, but after 5 years, the lower esophageal sphincter again becomes incompetent and injurious refluxate to the distal esophagus can recur. 7,8 It is well known that reflux of duodenal contents into the esophagus can produce adenocarcinoma, 39–42 and we believe that this could occur in these patients with Barrett’s. That is why we have changed our surgical approach in patients with long-segment Barrett’s with intestinal metaplasia: we now perform acid suppression (by vagotomy-partial gastrectomy) and duodenal diversion (by a Roux-en-Y loop 60 cm long), as will be reported elsewhere.

The other interesting finding of this prospective study is that we showed, probably for the first time in humans, the progression from fundic to a first metaplastic change to cardiac mucosa, then later a second metaplastic change to intestinal metaplasia, and 2 to 4 years later the appearance of low-grade dysplasia. In many of our patients, several endoscopic procedures and biopsy specimens were taken every 2 years; in this way we could follow the histologic changes. We stress again the importance of close endoscopic and biopsy surveillance in patients with Barrett’s who undergo surgical treatment.

In summary, patients with Barrett’s treated by classic antireflux surgery can progress to dysplastic changes and even to adenocarcinoma in some instances. Not all are symptomatic; therefore, close endoscopic surveillance is needed. We also outlined the metaplastic changes from fundic to cardiac and then to intestinal metaplasia at the distal esophagus.

Footnotes

Correspondence: Attila Csendes, MD, Department of Surgery, Hospital J.J. Aguirre, Santos Dumont No. 999, Santiago, Chile.

Accepted for publication August 7, 2001.

References

- 1.Loustarinen M. Nissen fundoplication for reflux esophagitis. Ann Surg 1993; 217: 329–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosseti ME, Liebermann-Heffert D, Braun RB. The “Rossetti” modification of the Nissen fundoplication: technique and results. Dis Esoph 1996; 9: 251–257. [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeMeester TR. The “DeMeester” modification: technique and results. Dis Esoph 1996; 9: 258–262. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siewert JR, Stein HJ. Technical details, long-term outcome and causes of failure. Dis Esoph 1996; 9: 278–284. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Csendes A, Braghetto I, Korn O, et al. Late subjective and objective evaluation of antireflux surgery in patients with reflux esophagitis. Analysis of 215 patients. Surgery 1989; 117: 374–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hill LD, Tahias JA. An effective operation for hiatal hernia: an eight-year appraisal. Ann Surg 1967; 166: 681–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Csendes A, Braghetto I, Burdiles P, et al. Long-term results of classic antireflux surgery in 152 patients with Barrett’s esophagus: clinical radiologic, endoscopic, manometric and acid reflux test analysis before and late after operation. Surgery 1998; 126: 645–645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Csendes A, Burdiles P, Korn O, et al. Late results of a randomized clinical trial comparing total fundoplication versus calibration of the cardia with posterior gastropexy. Br J Surg 2000; 87: 289–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brand DL, Yenisaker JT, Gelfand M, et al. Regression of columnar esophageal (Barrett’s) epithelium after anti-reflux surgery. N Engl J Med 1980; 302: 844–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skinner DB, Walther BC, Riddell RH, et al. Barrett’s esophagus: comparison of benign and malignant cases. Ann Surg 1983; 198: 554–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Starnes VA, Adkins RB, Ballinger JF, et al. Barrett’s esophagus. A surgical entity. Arch Surg 1984; 119: 563–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeMeester TR, Attwood SEA, Smyrk TC, et al. Surgical therapy in Barrett’s esophagus. Ann Surg 1990; 212: 528–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williamson WA, Ellis HE, Gilb P, et al. Effect of antireflux operation on Barrett’s mucosa. Ann Thorac Surg 1990; 49: 537–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McEntee GP, Stuart RC, Byrne PS, et al. An evaluation of surgical and medical treatment of Barrett’s esophagus. Gullet 1991; 1: 169–172. [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCallum RW, Polepalle S, Dawenport K, et al. Role of antireflux surgery against dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology 1991; 100: A121. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Attwood SEA, Barlow AP, Norris TC, et al. Barrett’s esophagus: effect of antireflux surgery on symptoms control and development of complications. Br J Surg 1992; 79: 1050–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sagar PM, Ackroyd R, Hosie KB, et al. Regression and progression of Barrett’s esophagus after antireflux surgery. Br J Surg 1995; 82: 806–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ortiz A, Martinez de Haro LF, Parrilla P, et al. Consecutive treatment versus antireflux surgery in Barrett’s esophagus: long-term results of a prospective study. Br J Surg 1996; 83: 274–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McDonald ML, Trastek UF, Allen MS, et al. Barrett’s esophagus: does an antireflux procedure reduce the need for endoscopic surveillance? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1996; 111: 1135–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeMeester SR, Campos GMR, DeMeester TR, et al. The impact of antireflux procedure on intestinal metaplasia of the cardia. J Gastro-intest Surg 1998; 228: 547–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patti MG, Arcenito M, Feo CV, et al. Barrett’s esophagus. A surgical disease. J Gastrointest Surg 1999; 3: 397–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Low DE, Levine DS, Dail DM, et al. Histological and anatomic changes in Barrett’s esophagus after antireflux surgery. Am J Gastroentest 1999; 94: 80–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zaninotto G, De Meester TR, Seenger W, et al. The lower esophageal sphincter in health and disease. Am J Surg 1988; 155: 104–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Visick AM. A study of failures after gastrectomy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1948; 3: 266–284. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Csendes A, Coronel M, Avendaño H, et al. Endoscopic location of squamous columnar junction in patients with gastroesophageal reflux. Rev Méd Chile 1996; 124: 1320–1324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Csendes A, Braghetto I, Maluenda F, et al. Peptic ulcer of the esophagus secondary to reflux esophagitis: clinical radiological endoscopic, histologic, manometric and isotopic studies in 127 patients. Gullet 1991; 1: 177–189. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Csendes A, Maluenda F, Braghetto I, et al. Location of the lower esophageal sphincter and the squamous-columnar junction in 109 healthy controls and 778 patients with different degrees of endoscopic esophagitis. Gut 1993; 34: 21–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reid BJ, Haggitt RC, Rubin CE, et al. Observer variation in the diagnosis of dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus. Hum Pathol 1988; 19: 166–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmidt HG, Riddell RH, Walther B, et al. Dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 1985; 110: 145–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Csendes A, Burdiles P, Alvarez F, et al. Manometric features of mechanically defective lower esophageal sphincter in control subjects and in patients with different degrees of gastroesophageal reflux. Dis Esoph 1996; 9: 290–294. [Google Scholar]

- 31.De Meester TR, Wang CI, Wemly JA. Technique, indications and clinical use of 24-h intraesophageal pH monitoring. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1980; 79: 656–670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Csendes A, Alvarez F, Burdiles P, et al. Magnitude of gastroesophageal reflux measured by 24-h esophageal pH monitoring according to the degree of endoscopic esophagitis. Rev Méd Chile 1994; 122: 59–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bechi P, Pucciani F, Baldini F, et al. Long-term ambulatory enterogastric reflux monitoring. Validation of a new fiberoptic technique. Dig Dis Sci 1993; 38: 1297–1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kauer NKH, Burdiles P, Ireland AP, et al. Does duodenal juice reflux intro the esophagus of patients with complicated GERD? Evaluation of a fiberoptic sensor for bilirubin. Am J Surg 1995; 169: 98–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Csendes A. A modified posterior cardiogastropexy for surgical treatment of gastroesophageal reflux with the adding of highly selective vagotomy and bougie calibration. In Stipa S, Belsey R; Moraldi A, eds. Medical and Surgical Problems of the Esophagus. Symposium No. 43. London: Academic Press; 1981:91–95.

- 36.Oster MT, Csendes A, Funch-Jensen P, et al. PVC and modified Hill procedure as surgical treatment of reflux esophagitis: results in 108 patients. World J Surg 1982; 6: 412–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Csendes A. Highly selective vagotomy, posterior gastropexy and calibration of the cardia. In Jamieson GJ. Surgery of the Esophagus. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1988.

- 38.Csendes A, Braghetto I, Korn O. Combined operation. In Pearson FG, ed. Esophageal Surgery. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1995.

- 39.Attwood SEA, DeMeester TR, Bremner CG, et al. Alkaline gastroesophageal reflux: implications in the development of complications in Barrett’s columnar-lined lower esophagus. Surgery 1989; 106: 764–770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Attwood SEA, Smyrk TC, DeMeester TR. Duodeno-esophageal reflux and the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma in rats. Surgery 1992; 111: 503–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Attwood SEA. Alkaline gastroesophageal reflux and esophageal carcinoma experimental evidence and clinical implications. Dis Esoph 1994; 7: 87–91. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith RRC, Hamilton SR, Boctwolt JK, et al. The spectrum of carcinoma arising in Barrett’s esophagus: a clinico-pathological study of 26 patients. Am J Surg Pathol 1984; 119: 563–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]