Abstract

Objective

To study the relationship of mammographic appearance of nonpalpable breast cancer to the pathologic characteristics.

Summary Background Data

The mammographic appearance of nonpalpable breast cancer may be associated with pathologic variables having prognostic significance, which could influence clinical management.

Methods

The authors correlated the mammographic appearance and pathologic characteristics of 543 nonpalpable malignancies diagnosed in a single institution between July 1993 and July 1999. Cancers were divided into four groups based on mammographic presentation: mass, calcification, mass with calcification, and architectural distortion.

Results

The majority of masses (95%), masses with calcifications (68%), and architectural distortions (79%) were due to invasive cancers, whereas the majority of calcifications (68%) were due to ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). Among invasive cancers, calcifications were associated with more extensive intraductal carcinoma, more Her2/neu immunoreactivity, and more necrosis of DCIS. Lymphatic invasion was more common in cancers presenting as a mass with calcifications. Sixty-nine percent of DCIS associated with invasive cancers presenting as calcifications were of high grade according to the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer. Calcifications in noninvasive tumors were associated with necrosis in DCIS. Two thirds of cancers presenting as architectural distortion had positive margins (65%) compared with 35% to 37% of other mammographic presentations. Mammographic presentation was not significantly related to tumor differentiation or estrogen or progesterone receptor status. The ratio of invasive to noninvasive malignancies increased progressively with increasing age from 1:1 in patients younger than 50 years of age to 3:1 in patients older than 70 years, whereas the proportion presenting as calcifications declined from 63% in patients younger than 50 years to 26% in patients older than 70 years.

Conclusions

Malignancies presenting as calcifications on mammography are most commonly DCIS. When invasive malignancies presented as calcifications, the calcifications were associated with accompanying high-grade DCIS, and the invasive cancers were often Her2/Neu positive. Mammographic masses with calcifications were associated with lymphatic invasion. Excisional biopsy margins were most commonly positive with architectural distortions. The mammographic appearance of nonpalpable malignancies is related to pathologic characteristics with prognostic value, which varies with patient age and influences clinical management.

Screening mammography has markedly increased the number of breast cancers detected when nonpalpable and often when noninvasive. Consequently, there has been a decline in the size and stage of breast cancers at presentation, resulting in improved survival, with more patients treated with breast conservation. Nonpalpable breast cancers may present radiographically as masses, calcifications, masses with calcifications, or architectural distortion. Numerous variables influence the radiologic appearance of nonpalpable breast cancers. Because breast density declines with increasing age, radiologic findings become more readily apparent, particularly for masses and architectural distortions. The radiographic appearance is also due to the biology of the tumors. Differences in the radiologic appearance of malignancies at different ages may be due to the biologic difference or to differences in the surrounding breast. Because the clinical behavior of a breast cancer is due to its biologic properties, the radiographic appearance of a nonpalpable breast cancer should predict the clinical course of the disease.

Several studies have noted an association between age and pathologic characteristics of both palpable and nonpalpable breast cancers, 1–7 and others have noted differences in the mammographic appearance of malignancies at different ages. 8–11 The relationship between the appearance of nonpalpable breast cancer and pathologic characteristics, which may have prognostic value, has not been well studied with consideration for changes with age in the mammographic appearance or pathology. 8–13 We studied the relationship between the mammographic appearance of nonpalpable breast cancers and their pathologic characteristics at different ages to determine whether mammographic appearance could have potential prognostic value or influence clinical management.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The pathology database of the Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City was used to identify women with breast cancer who underwent surgical biopsy after needle localization between July 1993 and July 1999. These data were matched to the records of the Department of Radiology. Five hundred forty-three patients who had both available mammographic reports and pathologic results corresponding to the mammographic lesion made up this study. Pathologic information was prospectively collected concerning patient age, tumor size, histopathologic type, differentiation, lymphatic invasion, extensive intraductal component, estrogen and progesterone receptor levels, Her2/neu immunoreactivity, involvement of axillary lymph nodes, surgical margin status, and type of surgery. In patients with multiple primary invasive tumors, the size of the largest infiltrating lesion was used. Margins were considered involved when invasive or noninvasive ductal carcinoma or invasive lobular carcinoma was present at the inked margin. Close margins represented tumor within 1 mm of the inked margin. Margins were considered clear when the distance between the tumor and the inked margin was at least 1 mm. Her2/neu immunoreactivity was measured in 118 instances. Histologic slides were initially read or, in a minority of instances, retrospectively reviewed by one of the authors (I.J.B.). Mammograms were read by five radiologists who specialize in breast radiology at the Department of Radiology, without knowledge of the pathologic findings.

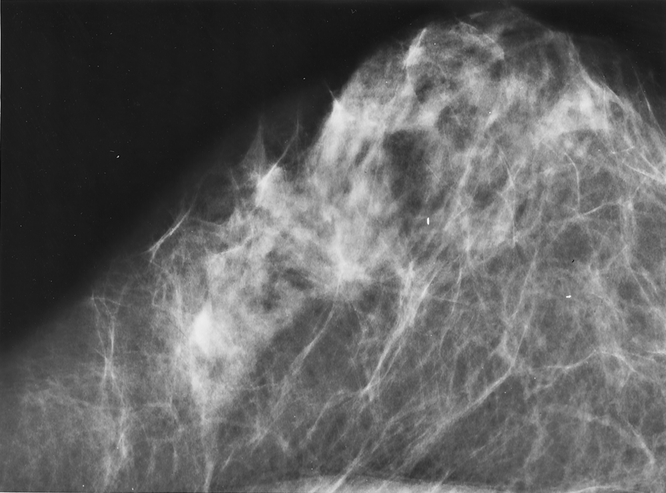

Patients were divided into four groups based on mammographic presentation: mass (Fig. 1), calcification (Fig. 2), mass with calcification (Fig. 3), and architectural distortion (Fig. 4). Pathologic findings were correlated with mammographic presentation. The data were analyzed using the SPSS statistical program (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The significance of differences in categorical variables was evaluated using the chi-square test. The significance of differences in continuous variables was evaluated using one-way analysis of variance followed by t tests if the one-way analysis was significant.

Figure 1. Malignant breast tumor presenting as a mass on mammogram.

Figure 2. Malignant breast tumor presenting as calcifications on mammogram.

Figure 3. Malignant breast tumor presenting as a mass with associated calcifications on mammogram.

Figure 4. Malignant breast tumor presenting as an architectural distortion on mammogram.

RESULTS

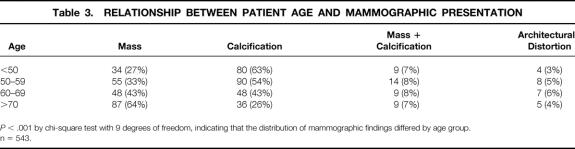

The 543 patients ranged in age from 30 to 92 years (mean 59). Forty-one percent (n = 224) of the patients had a mammographic mass, 47% (n = 254) had calcifications, 8% (n = 41) had a mammographic mass with calcifications, and 4% (n = 24) had architectural distortion (Table 1). Initial tissue sampling of the mammographic abnormality was performed with surgical biopsy in 90% (n = 489) of the patients and core needle biopsy in 10% (n = 54).

Table 1. PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS

* Denominator is all invasive tumors (infiltrating ductal plus infiltrating lobular).

† Denominator is all infiltrating ductal tumors.

‡ Denominator is all surgical biopsies where surgical margin status was known.

Fifty-six percent (n = 302) of the 543 cancers were infiltrating ductal, 8% (n = 43) were infiltrating lobular, and 36% (n = 198) were ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). The invasive tumors (infiltrating ductal plus infiltrating lobular) ranged in size from microscopic (<1 mm) to 3 cm (mean 1 cm). Eight percent (n = 23) of the invasive ductal tumors were well differentiated, 53% (n = 145) were moderately differentiated, and 39% (n = 105) were poorly differentiated. Thirty-two percent (n = 110) of the 344 invasive tumors were associated with an extensive intraductal component. Lymphatic invasion was identified in 21% of the invasive cancers (n = 71), and 25% (n = 62) had axillary lymph node metastasis (248 patients had axillary node dissection at Mount Sinai Hospital). Eighty percent of the tumors (n = 435) were positive for estrogen receptor, and 68% (n = 367) were positive for progesterone receptor. Thirty-five percent (n = 147) of the surgical specimens that were removed by needle localization had negative margins pathologically, 37% (n = 156) had positive margins, and 28% (n = 116) had close margins. Margin status was unknown in 70 specimens.

Mammographic presentation was predictive of specific pathologic characteristics of both invasive and noninvasive cancers. The majority of masses, masses with calcifications, and architectural distortions were due to invasive cancers, whereas the majority of calcifications were due to DCIS (P < .001, Table 2). Invasive cancers presenting as masses were less likely to have an extensive intraductal component (P < .001). Among invasive cancers, calcifications were associated with extensive intraductal carcinoma (P < .001), increased Her2/neu immunoreactivity (P = .013), and necrosis (P < .001). Invasive cancers presenting as masses with calcifications were associated with lymphatic invasion (P < .001). When calcifications resulting from DCIS were present with invasive cancer, 69% were of high grade according to the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer. Among noninvasive cancers, calcifications were associated with necrosis in the tumor (P < .001). Patients presenting with a mass on mammogram had the highest likelihood of pathologically negative resection margins, and patients with architectural distortion had the highest likelihood of positive margins (P < .001). Mammographic presentation was not significantly related to tumor differentiation or estrogen or progesterone receptor status.

Table 2. VARIABLES SIGNIFICANTLY RELATED TO MAMMOGRAPHIC PRESENTATION

DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ.

*P value is from chi-square test.

† European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer grade in the noninvasive component of invasive tumors.

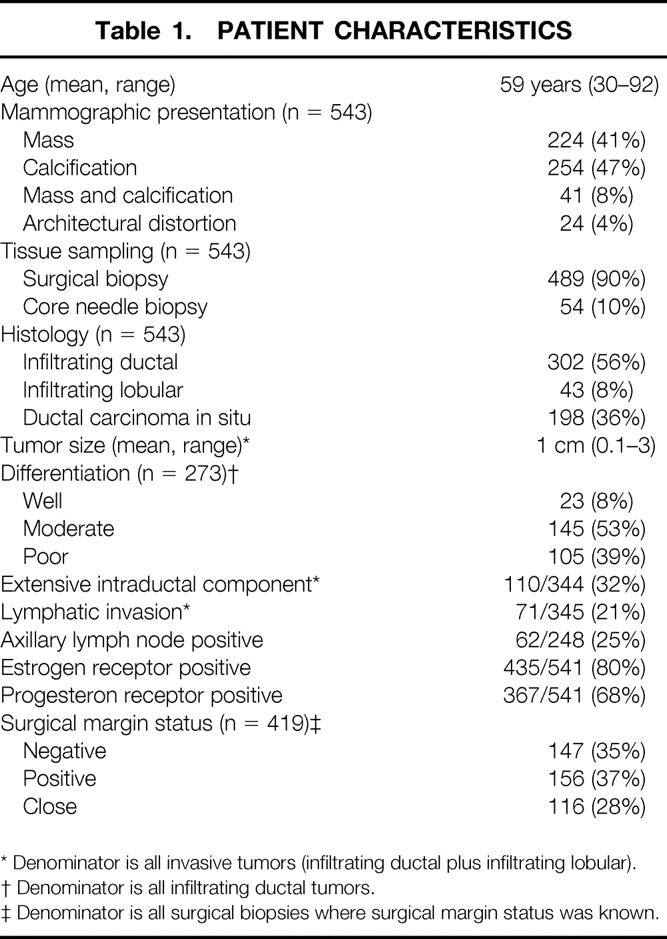

Patient age was predictive of mammographic findings, histology, and invasive tumor size. The proportion of malignancies presenting as masses increased with age, and those presenting as calcifications declined (Table 3). The proportion of invasive malignancies increased progressively with increasing age (Table 4). In addition, patients younger than 40 years were significantly more likely to present with T1c tumors (Table 5).

Table 3. RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PATIENT AGE AND MAMMOGRAPHIC PRESENTATION

P < .001 by chi-square test with 9 degrees of freedom, indicating that the distribution of mammographic findings differed by age group.

n = 543.

Table 4. RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PATIENT AGE AND HISTOLOGY

P = .002 by chi-square test with 6 degree of freedom, indicating that histologic findings differed by age group.

n = 543.

Table 5. RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PATIENT AGE AND INVASIVE TUMOR SIZE

P = .04 by chi-square test with 12 degree of freedom, indicating that tumor size differed by age group.

n = 341.

Mammographic presentation was significantly related to pathologic tumor size (P < .001). Patients presenting with calcifications had significantly smaller invasive tumors (mean [standard error of the mean] = 7.8 [0.7] mm) than patients presenting with masses (10.8 [0.4] mm), masses with calcification (11.3 [1] mm), or architectural distortions (12.6 [2.3] mm). Axillary nodal involvement was not significantly related to mammographic presentation (P = .623). Twenty-three percent of mammographic masses (n = 36), 24% of calcifications (n = 13), 35% of masses with associated calcifications (n = 8), and 29% of architectural distortions (n = 5) had positive axillary lymph nodes.

DISCUSSION

Radiographic findings have different significance in younger patients than in older patients because nonpalpable breast malignancies have various radiographic appearances that vary with patient age. Because mammographically detected nonpalpable malignancies in young patients most often present as microcalcifications resulting from DCIS, whereas in older patients nonpalpable malignancies present as masses resulting from invasive ductal carcinoma, 8–11 mammographic calcifications must be viewed with greater suspicion in young women by both surgeons and radiologists. This suggests that with time, the noninvasive tumors in young women become invasive as they age. However, this is unlikely because older patients with invasive cancers had smaller tumors than young patients with invasive cancers. This supports the hypothesis that the biology of breast cancer is different at different ages. 1,3,6,7,14,15

Higher rates of local recurrence after breast conservation in young patients have been attributed to these biologic differences. 2,3,14,15 In addition to young age, the presence of mammographic calcification has also been associated with higher rates of local recurrence. 16 Because we and others 8,9,11 found that calcifications detected by screening mammography in young patients are more frequently a manifestation of DCIS, the value of mammography in young patients may be increasing. In addition, local recurrence is more frequent with cancers with extensive intraductal carcinoma manifesting as calcifications. 17–20 This should cause the clinician to plan wider surgical excision to obtain clear margins when malignancies present as calcifications.

Calcifications have different implications for noninvasive and invasive cancer depending on whether they are associated with a mass. When accompanying invasive cancer, the DCIS is usually of high grade according to the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and the invasive cancer is often Her2/neu positive. Invasive malignancies presenting as calcifications on mammography were associated with extensive intraductal carcinoma, 21,22 and because extensive intraductal carcinoma has been associated with a high rate of positive margins and local recurrence, 17–20 more tissue will also have to be removed with these cancers to obtain clear margins. However, invasive tumors presenting as masses with calcification had the lowest rate of positive margins, but they had the highest rate of lymphatic invasion, which should increase the clinician’s suspicion that nodal involvement may be present.

Patients who had architectural distortion on mammography were more likely to have positive margins than patients with masses or calcifications. This may be because architectural distortion on mammography is most commonly due to benign conditions, causing the surgeon to excise with minimal margins. Tumors presenting as architectural distortions on mammography were also significantly larger than tumors presenting with other mammographic abnormalities. Patients undergoing biopsy for nonpalpable architectural distortions should be excised more widely to reduce the risk of positive margins. Several histopathologic parameters have been related to having clear margins on excisional biopsy, and some of these parameters have been related to subsequent local recurrence. 23–26 However, factors associated with clear margins with palpable cancers are not associated with clear margins with nonpalpable cancers. Clear margins with palpable cancers have been related to preoperative diagnosis by needle biopsy, absence of calcifications, and small tumor size. 23,25 In our study of nonpalpable breast carcinomas, none of the patients were diagnosed by fine-needle biopsy, and the likelihood of clear margins with calcifications was equal to that of masses.

The radiographic appearance of nonpalpable breast cancers reflects the biology of the disease. Because nonpalpable malignancies in young patients most commonly present with calcifications, mammographic calcifications in young women should be viewed with suspicion. Calcifications in nonpalpable invasive cancers reflect high-grade adjacent DCIS. Nonpalpable malignancies presenting as architectural distortions also have a high rate of positive surgical margins on excisional biopsy. The need for wider surgical excision to obtain clear margins should be anticipated with all of these mammographic presentations. Consideration for management of the axillary nodes is indicated for nonpalpable malignancies presenting as masses with calcifications because they have a high rate of lymphatic invasion and positive axillary nodes. Once a mammographic abnormality is diagnosed as carcinoma by core needle or mammotome biopsy, our observations should help clinicians to plan surgical treatment based on mammographic presentation.

Footnotes

Supported by the Susan G. Komen Foundation.

Correspondence: Paul Ian Tartter, MD, The Comprehensive Breast Center, 425 West 59th Street, Suite 7A, New York, NY. 10019.

E-mail: paul_tartter@slrhc.org

Csaba Gajdos, MD, is currently at the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center, Northwestern University Medical School, Chicago, Illinois.

Accepted for publication June 4, 2001.

References

- 1.Kollias J, Elston CW, Ellis IO, et al. Early-onset breast cancer: histopathological and prognostic considerations. Br J Cancer 1997; 75: 1318–1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim SH, Simkovich-Heerdt A, Tran KN, et al. Women 35 years of age or younger have higher locoregional relapse rates after undergoing breast conservation therapy. J Am Coll Surg 1998; 187: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fowble BL, Schultz DJ, Overmoyer B, et al. The influence of young age on outcome in early-stage breast cancer. Intl J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1994; 30: 23–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De La Rochefordiere A, Asselain B, Campana F, et al. Age as prognostic factor in premenopausal breast carcinoma. Lancet 1993; 341: 1039–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson BO, Senie RT, Vetto JT, et al. Improved survival in young women with breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 1995; 2: 407–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walker RA, Lees E, Webb M’ B, Dearing SJ. Breast carcinomas occurring in young women (<35 years) are different. Br J Cancer 1996; 74: 1796–1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fisher CJ, Egan MK, Smith P, et al. Histopathology of breast cancer in relation to age. Br J Cancer 1997; 75: 593–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hermann, Janus C, Schwartz IS, et al. Occult malignant breast lesions in 114 patients: Relationship to age and the presence of microcalcifications. Radiology 1988; 169: 321–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wazer DE, Gage I, Horner MJ, et al. Age-related differences in patients with nonpalpable breast carcinomas. Cancer 1996; 78: 1432–1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Papatestas AE, Hermann D, Hermann G, et al. Surgery for nonpalpable breast lesions. Arch Surg 1990; 125: 399–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ewans PW, Starr AL, Bennos ES. Comparison of the relative incidence of impalpable invasive breast carcinoma and ductal carcinoma in situ in cancers detected in patients older and younger than 50 years of age. Radiology 1997; 204: 489–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kopland KH, Hiatt JR, Irving C, Giuliano AE. The pathology of nonpalpable breast cancer. Am Surg 1990; 12: 782–787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yokoe T, Maemura M, Takei H, et al. Efficacy of mammography for detecting early breast cancer in women under 50. Anticancer Res 1998; 18: 4709–4712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nixon AJ, Neuberg D, Hayes DF, et al. Relationship of patient age to pathologic features of the tumor and prognosis for patients with stage I or II breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 1994; 12: 888–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurtz JM, Jacquemier J, Amalric R, et al. Why are local recurrences after breast-conserving therapy more frequent in younger patients? J Clin Oncol 1990; 8: 591–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kini VR, Vicini FA, Frazier R, et al. Mammographic, pathologic and treatment-related factors associated with local recurrence in patients with early-stage breast cancer treated with breast conserving therapy. Intl J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1999; 43: 341–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacquemier J, Kurtz JM, Amalric R, et al. An assessment of extensive intraductal component as a risk factor for local recurrence after breast-conserving therapy. Br J Cancer 1990; 61: 873–876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kurtz JM, Jacquemier J, Amalric R, et al. Risk factors for breast recurrence in premenopausal and postmenopausal patients with ductal cancers treated by conservation therapy. Cancer 1990; 65: 1867–1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Voogd AC, Petersen JL, Crommelin MA, et al. Histological determinants for different types of local recurrence after breast-conserving therapy of invasive breast cancer. Dutch Study Group on Local Recurrence after Breast Conservation. Eur J Cancer 1999; 35: 1828–1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macmillan RD, Purushotham AD, George WD. Local recurrence after breast-conserving surgery for breast cancer. Br J Surg 1996; 83: 149–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Healey EA, Osteen RT, Schnitt SJ, et al. Can the clinical and mammographic findings at presentation predict the presence of an extensive intraductal component in early-stage breast cancer? Intl J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1989; 17: 1217–1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wazer DE, Schmidt-Ullrich R, Homer MJ, et al. The utility of preoperative physical examination and mammography for detecting an extensive intraductal component in early-stage breast carcinoma. Breast Dis 1990; 3: 181–185. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tartter PI, Bleiweiss IJ, Levchenko S. Factors associated with clear biopsy margins and clear reexcision margins in breast cancer specimens from candidates for breast conservation. J Am Coll Surg 1997; 185: 268–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beron PJ, Horwitz EM, Martinez AA, et al. Pathologic and mammographic findings predicting the adequacy of tumor excision before breast- conserving therapy. Am J Radiol 1996; 167: 1409–1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kollias J, Gill PG, Beamond B, et al. Clinical and radiological preditors of complete excision in breast-conserving surgery for primary breast cancer. Aust NZ J Surg 1998; 68: 702–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chinyama CN, Davies JD, Rayter Z, Farndon JR. Factors affecting surgical margin clearance in screen-detected breast cancer and the effect of cavity biopsies on residual disease. Eur J Surg Oncol 1997; 23: 123–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]