Abstract

Objective

To compare laparoscopic with open hernia repair in a randomized clinical trial at a median follow-up of 5 years.

Summary Background Data

Follow-up of patients in clinical trials evaluating laparoscopic hernia repair has been short.

Methods

Of 379 consecutive patients admitted for surgery under the care of one surgeon, 300 were randomized to totally extraperitoneal hernia repair or open repair, with the open operation individualized to the patient’s age and hernia type. All patients, both randomized and nonrandomized, were followed up by clinical examination annually by an independent observer.

Results

Recurrence rates were similar for both randomized groups. In 1 of the 79 nonrandomized patients, a recurrent hernia developed. Groin or testicular pain was the most common symptom on follow-up of randomized patients. The most common reason for reoperation was development of a contralateral hernia, which was noted in 9% of patients; 11% of all patients died on follow-up, mainly as a result of cardiovascular disease or cancer.

Conclusions

These data show a similar outcome for laparoscopic and open hernia repair, and both procedures have a place in managing this common problem.

Since the concept of laparoscopic hernia repair was first described by Ger 1 in 1982, the surgical procedure has undergone many changes. Fundamental to these has been a move to the preperitoneal approach, with the use of a large piece of mesh to cover the myopectineal orifice after reduction of the hernia sac. This method of repair can be accomplished either totally extraperitoneally (TEP) or transabdominally (TAPP), depending on the experience or preference of the laparoscopic surgeon.

The successful use of mesh in laparoscopic surgery, along with the excellent results reported from specialist hernia centers, has encouraged the widespread use of mesh for open hernia repair. In some countries 2 more than 90% of hernia repairs are undertaken using mesh, despite concerns about its long-term safety, particularly in young patients. A plea for individualization of hernia repair has been made by authors such as Nyhus, 3 who recommended sutured repair for indirect inguinal hernias in young patients and for femoral hernias, reserving the use of mesh for direct and recurrent hernias. The aim of this study was to compare patient outcome at a median follow-up of 5 years after open hernia repair, individualizing the repair to the patient’s age and type of hernia, with the TEP approach for all hernias in a randomized clinical trial.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

All patients presenting under the care of one surgeon between January 1994 and March 1997 were asked for their consent to be randomized to laparoscopic or open hernia repair. This trial was part of a larger multicenter trial, and approval from the hospital’s ethics committee had been obtained. 4 Patients were excluded if they were medically unfit for a general anesthetic, had a previous lower midline or paramedian incision, had an acute or irreducible inguinoscrotal hernia, had an uncorrected coagulation disorder, or were pregnant. The surgeon had performed 40 TAPPs and 30 TEPs before beginning to randomize patients. Randomization was by sealed envelope with computer-generated random allocation for the first 50 patients and through a centralized telephone randomization service for the remainder.

Patients randomized to the open arm of the trial had the following operations. For those with a primary inguinal hernia who were younger than 30 with a Nyhus type 1 or type 2 hernia, 3 a herniotomy with tightening of the deep internal ring was performed. All other patients with a primary inguinal hernia underwent an open tension-free hernioplasty similar to that described by Lichtenstein et al. 5 Patients with bilateral or recurrent hernias underwent an open preperitoneal repair using mesh; the operation was modified from the original description by Stoppa and Warlaumount 6 in that access was through a lower transverse abdominal incision placed approximately halfway between the level of the anterior superior iliac spine and the pubic symphysis. Patients with a primary femoral hernia underwent a sutured repair through a low approach.

Patients randomized to laparoscopic repair underwent a totally extraperitoneal laparoscopic repair, as previously described. 7 The preperitoneal space was entered just below the umbilicus and enlarged using gentle blunt dissection with a laparoscope. Two 5-mm ports were placed in the midline under direct vision, and reusable cannulas and instruments were used. After the hernia sac was reduced, a 15 × 10-cm polypropylene mesh was used to cover the myopectineal orifice in all patients and was fixed to the pectineal ligament only in patients with a femoral hernia or a large direct inguinal hernia that encroached on the ligament.

Nonrandomized patients underwent open repair; repair was individualized as for the open randomized group unless a laparoscopic repair was requested. All patients unfit for general anesthesia had a local anesthetic Lichtenstein repair.

All patients were followed up at a hernia clinic and examined by a research nurse and research fellow who had not participated in the original operation. Patients were seen at 1 week and annually thereafter. Patients who failed to keep their annual clinic appointment were given the option of a further appointment at a more suitable date or a visit to their home if they could not make it to the outpatient clinic. For those who did not comply with this, all hospital admissions subsequent to their hernia repair were checked to ensure that they did not have a further operation for a recurrent or contralateral hernia.

Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome measures of this study were hernia recurrence and chronic pain at a median follow-up of 5 years. Data were analyzed on an intent-to-treat basis. For analysis of differences between groups that were not normally distributed we used a Mann-Whitney test. Chi-square or Fisher exact test was used to compare proportions. Between-group differences were expressed when appropriate with 90% confidence intervals (CI) and relevant probability values. All data were analyzed using SPSS release 9.0.0 standard version (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Patients entered in this trial were part of a larger multicenter study where funding for clinical follow-up was limited to 1 year; that study has been reported. 4

RESULTS

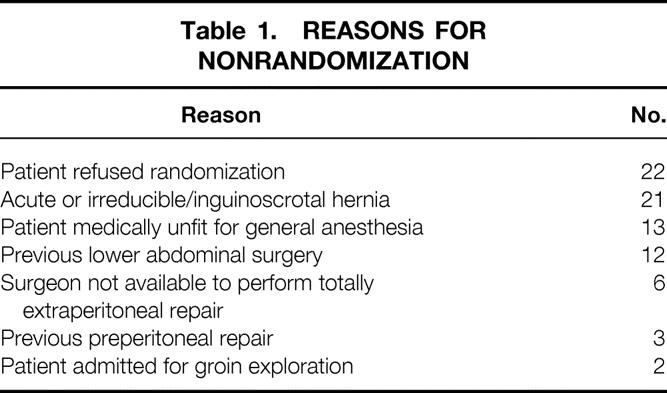

During the study period, 379 consecutive patients with a groin hernia underwent surgery. Three hundred were randomized, 149 to TEP and 151 to open repair; 79 either met the exclusion criteria or refused randomization (Table 1). Because more than a quarter of nonrandomized patients presented acutely and/or had a large irreducible inguinoscrotal hernia, all were followed up clinically as a potential worst-case comparison group.

Table 1. REASONS FOR NONRANDOMIZATION

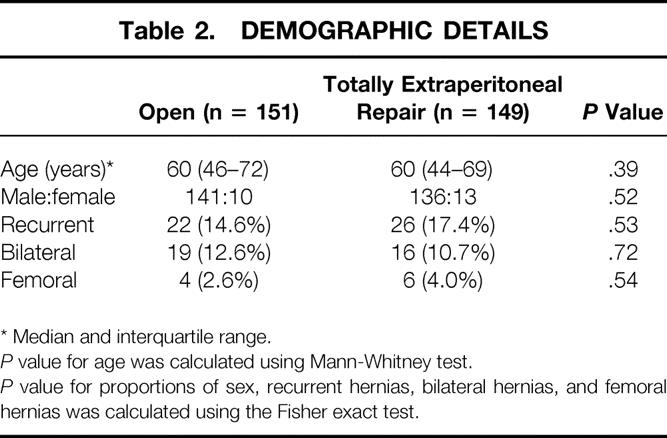

Randomized patients were matched for age, sex, and type of hernia, with approximately 70% of patients in each group having a unilateral primary inguinal hernia (Table 2). All operations in the laparoscopic group were performed or supervised by the consultant. In the open group all operations were performed by a surgical trainee, supervised by the consultant in 90% of operations and by a senior trainee in 10%. In the open group the policy of individualizing repair led to 90% of patients having a mesh repair (Lichtenstein or Stoppa). Six percent of patients in the laparoscopic group were converted to open surgery. The reasons for conversion were large tears in the peritoneum (five patients) and technical difficulty reducing the hernia or placing the mesh (two patients); two patients were randomized in error with a Pfannenstiel incision. In addition, three randomized patients (two in the laparoscopic group and one in the open group) had a failed repair at surgery. Both in the laparoscopic group had a large direct inguinal hernia (>5 cm) and coughed the mesh into the defect on awakening from general anesthesia. In both patients the mesh had been stapled and the operations were converted to an open tension-free mesh repair. One male patient in the open group had a femoral hernia missed at surgery. This error was noticed at the patient’s first clinic visit and the hernia was repaired at a subsequent operation. There were no significant intraoperative or postoperative complications; 2% of patients in both groups had a wound infection and a similar number had acute urinary retention.

Table 2. DEMOGRAPHIC DETAILS

* Median and interquartile range.

P value for age was calculated using Mann-Whitney test.

P value for proportions of sex, recurrent hernias, bilateral hernias, and femoral hernias was calculated using the Fisher exact test.

Follow-Up

All patients, including those who were not randomized, have been followed for a median of 60 months (minimum 40, maximum 80). The rate of clinical follow-up was 91% for year 1, 80% for year 2, 70% for year 3, and 48% for year 5. During follow-up 41 (11%) patients died, including 14 nonrandomized patients, from either cardiovascular disease or cancer. Less than 1% of patients had left the region. For those who did not present for clinical examination, it was possible to check all their hospital admissions to exclude operation for a recurrent or contralateral groin hernia. In 35 patients (including 8 nonrandomized patients) a new contralateral hernia developed. In three patients a paraumbilical hernia developed, and an incisional hernia developed in one at the site of a previous appendectomy scar during the follow-up period. Eighteen of the 35 patients with a contralateral inguinal hernia underwent repair; 4 were medically unfit or refused a further operation, and 13 are asymptomatic and are continuing follow-up.

Hernia Recurrence

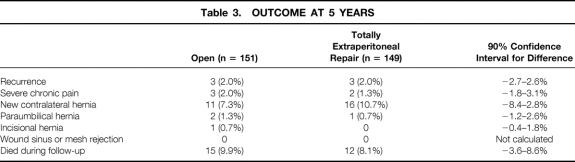

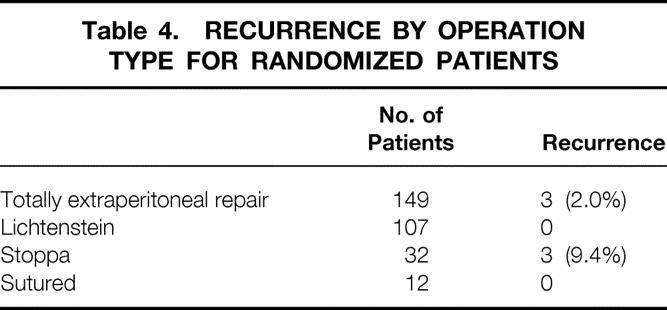

Six hernia recurrences were noted during the 5-year follow-up period in randomized patients, 3 (2%) in the open group versus 3 (2%) in the TEP group (90% CI for difference, −2.7–2.6%, P = .987) (Table 3). All hernia recurrences in patients randomized to the open group occurred after an open preperitoneal repair for bilateral hernias. Two of these were in patients with large indirect inguinal hernias; one was incisional, occurring above the lower transverse abdominal incision used for access to repair these hernias. All recurrences after laparoscopic repair occurred in patients with large direct inguinal defects, with the recurrence appearing above the superior border of the mesh.

Table 3. OUTCOME AT 5 YEARS

In only one patient (1.3%) in the nonrandomized group did a recurrent hernia develop. This also occurred after repair of large bilateral indirect hernias using an open preperitoneal repair. Of the total of seven hernia recurrences in randomized and nonrandomized patients, four were asymptomatic at presentation, and six of the seven have been repaired. The patient with the incisional recurrence is asymptomatic and does not wish a further operation. The pattern and timing of recurrences was as follows: two at year 1, two at year 2, two at year 3, and one at year 4. All recurrent hernias were repaired using an open tension-free hernioplasty. There were no recurrences in the 60 patients undergoing repair for a recurrent hernia, and no patient with a Lichtenstein repair for a primary inguinal hernia had a recurrence (Table 4).

Table 4. RECURRENCE BY OPERATION TYPE FOR RANDOMIZED PATIENTS

Chronic Pain

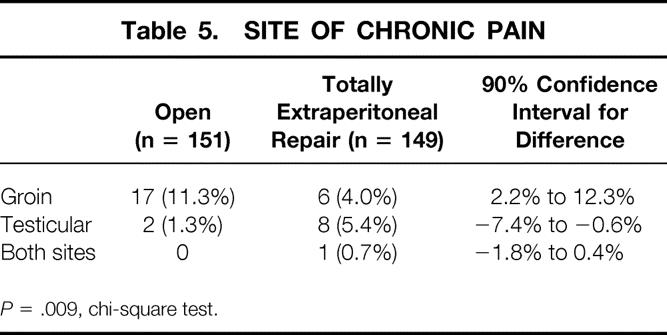

Although there was no significant difference in chronic pain (pain present at year 1 or at subsequent follow-up) between the randomized groups (90% CI for difference, −3.5–8.6%, P = .49), patients undergoing laparoscopic repair were significantly more likely to have testicular pain and those undergoing open repair were significantly more likely to have pain along the inguinal ligament and were maximally tender over the pubic tubercle (Table 5). This pain was made worse by movement and appeared nociceptive (related to tissue damage) in origin. Five randomized patients were referred to a specialized pain clinic for continuing severe pain, three in the open group and two in the TEP group. After treatment, all patients’ chronic pain resolved at a median of 4 years after their hernia repair.

Table 5. SITE OF CHRONIC PAIN

P = .009, chi-square test.

Eight (10%) of the 79 patients in the nonrandomized group had chronic pain. Patients with chronic pain were significantly more likely to report pain at presentation from their hernia compared with those who remained asymptomatic at follow-up (88% vs. 59%, P < .001). These patients were also significantly less likely to have returned to work in the home at 3 months after surgery (80% vs. 97.5%, P < .001) or social activity (78% vs. 94.5%, P < .001) compared with their pain-free counterparts.

DISCUSSION

This study shows a satisfactory outcome for both open and laparoscopic hernia repairs in a randomized clinical trial. The recurrence rate for both operations was low, even if one corrects for the fact that some patients who did not return for clinical examination may have an asymptomatic recurrence. The incidence of severe chronic pain affecting working and leisure activity was also acceptable and significantly lower than that reported by Cunningham et al 8 in their series of nonmesh repairs.

This study differs from other randomized trials evaluating laparoscopic hernia repair in several ways. 9 Follow-up of patients has been for a median of 5 years and has included nonrandomized patients. We believe both aspects are important because recurrence after mesh repairs may occur several years after the primary operation, and continued follow-up of these patients is necessary. It is also likely that the patients with more difficult hernias (e.g., acute or irreducible inguinoscrotal hernias) are excluded from randomization and follow-up in most studies, thus leaving us with little information on the long-term outcome of this group of patients. Clinical examination at follow-up was performed by a surgeon and nurse who had not participated in the patient’s operation; this should eliminate any bias that may occur. Finally, the study was pragmatic and reflects the median age range of patients with a groin hernia in the region. 2 Eleven percent had died of cardiovascular disease or cancer at 5 years, and this is in keeping with the expected death rate for this age group of patients. 10

All patients in the laparoscopic group who had a hernia recurrence did so after repair of a large direct inguinal hernia and in the first year of the trial. Although a mesh size of 15 × 10 cm had been used and was stapled to the pectineal ligament in all instances, it is likely that this is too small for very large direct inguinal hernias (>5 cm in diameter), and a mesh size of 15 × 15 cm might have been more appropriate. It is also likely that technical error was an important factor in the development of hernia recurrence in the open group in that all the recurrences followed open preperitoneal repair for large bilateral indirect inguinal hernias. All occurred lateral to the mesh, which may not have been placed far enough beyond the internal ring to prevent this from happening. The fact that these operations were carried out through a transverse lower abdominal rather than a vertical incision may have contributed to this.

Eleven percent of patients reported chronic groin or testicular pain at some time during follow-up. These patients were significantly more likely to have pain at the hernia site on presentation; of those in whom severe pain developed, all had suffered from other chronic pain syndromes, such as backache or headache, in the past. Notwithstanding this, there was also evidence of a learning curve effect: patients randomized in the first year of the trial were twice as likely to have this problem. In the laparoscopic group this is likely to have resulted from excessive skeletonization of the cord, thereby damaging the genital branches of the genitofemoral nerve. In the open group the reason is less clear; however, in three of the four patients who went on to experience this problem, the operations were not supervised by a consultant.

All laparoscopic operations in this study were performed using a TEP approach. One of the disadvantages of this operation is the high conversion rate compared with the TAPP approach. These conversions usually occur as a result of tearing the peritoneum, particularly in elderly patients with little extraperitoneal fat. However, with increasing experience and greater use of the Trendelenburg position, this can be overcome. The other disadvantage of this operation compared with the TAPP approach is that unless the contralateral side is dissected, small asymptomatic contralateral hernias will be missed. In this study almost 10% of patients required operation for a contralateral hernia within the 5-year follow-up period. However, this must be balanced against the low but significant incidence of serious complications reported with the TAPP approach. 4,9

The major drawback of laparoscopic hernia repair over the open approach is the added cost, particularly when disposable instruments are used. 4 It has been our experience, however, that disposable instruments are unnecessary, and these operations can be undertaken satisfactorily without the use of balloons and so forth. The other disadvantage of laparoscopy compared with open hernia repair is that a general anesthetic is almost always necessary. Finally, and this may be the most serious problem associated with laparoscopic hernia repair, the learning curve is long. 11 The principal reasons for the long learning curve are the surgeon’s lack of familiarity with the preperitoneal anatomy and the time it takes to develop the skills to operate in a confined space.

The concept of individualizing hernia repair, as was performed for patients randomized to the open arm of this trial, is important. However, just as all patients undergoing groin hernia repair do not need mesh, an open approach is not necessary or desirable for all patients. The laparoscopic approach provides unrivalled views of the preperitoneal space and allows accurate placement of the mesh, completely covering the myopectineal orifice. This makes it an excellent operation for repair of a recurrent hernia after a failed anterior approach. It also has advantages for bilateral hernias and selected patients with a primary hernia requiring a rapid convalescence. These operations should be undertaken by experienced laparoscopic surgeons with an interest in hernia repair, with laparoscopy maintaining a key role in managing patients with this common condition.

Footnotes

Funded in part by the Medical Research Council.

Correspondence: Patrick J. O’Dwyer, MCh, FRCS, Professor of Gastrointestinal Surgery, University Department of Surgery, Western Infirmary, Glasgow, G11 6NT, U.K.

E-mail: pjod2j@clinmed.gla.ac.uk

Accepted for publication August 10, 2001.

References

- 1.Ger R. The management of certain abdominal hernia by intra-abdominal closure of the neck of the sac. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1982; 64: 342–344. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hair A, Duffy K, McLean J, et al. Groin hernia repair in Scotland. Br J Surg 2000; 87: 1722–1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nyhus LM. Individualisation of hernia repair: A new era. Surgery 1993; 114: 1–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MRC Laparoscopic Groin Hernia Trial Group. Laparoscopic versus open repair of groin hernia: A randomised comparison. Lancet 1999; 354: 185–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lichtenstein IL, Shullman AG, Amid PK, et al. The tension-free hernioplasty. Am J Surg 1989; 157: 188–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stoppa RE, Warlaumount CK. The preperitoneal approach and prosthetic repair of groin hernias. In: Nyhus LM, Coldon RE, eds. Hernia, 4th ed. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1995: 118–210.

- 7.O’Dwyer PJ. Laparoscopic hernia repair. In: Devlin BH, Kingsnorth A, eds. Management of abdominal hernias, 2d ed. London: Chapman & Hall, 1998: 177–184.

- 8.Cunningham J, Temple WJ, Mitchell P, et al. Co-operative Hernia Study. Pain in the postrepair patient. Ann Surg 1996; 224: 598–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.EU Hernia Trialists Collaboration. Laparoscopic compared with open methods of groin hernia repair: Systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Br J Surg 2000; 87: 860–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Death rates by sex and age, Scotland 1946–1999. General Registrar Office for Scotland Annual Reports, 1999.

- 11.Wright D, O’Dwyer PJ. The learning curve for laparoscopic hernia repair. In: Cuschieri A, MacFadyen BV Jr, eds. Seminars in laparoscopic surgery. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1998: 227–232. [DOI] [PubMed]