Abstract

Objective

To audit the results of endoscopic transanal resection of tumor (ETAR) performed by a single surgeon at a specialized colorectal unit during a 10- year period.

Summary Background Data

A minimally invasive surgical technique, ETAR has enabled much progress to be made in the development of local treatment strategies for rectal neoplasia. It can be used in both the curative and palliative management of rectal lesions and is a treatment option for patients who would be unable to tolerate major surgery.

Methods

The surgical outcome of 104 patients (43 women, 61 men) undergoing ETAR under the care of a single surgeon between 1989 and 1999 was reviewed. Patients were identified from the consultant’s personal records and cross-referenced with operating room logs. Data were collected retrospectively and no patients were lost to follow-up.

Results

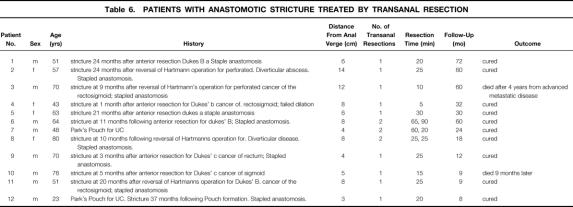

One hundred four patients underwent 163 procedures during the study period. Follow-up ranged from 6 months to 10 years. Seventy-five patients with a pre-ETAR diagnosis of benign rectal adenoma underwent resection. In 60 patients, the diagnosis was confirmed to be benign; 30 of these were treated with a single resection and 28 with multiple resections. There were two technical failures, both a result of high mobility of the lesion. In no patients did carcinoma subsequently develop. In the remaining 15 patients the final histology demonstrated a malignancy; 9 patients underwent an open surgical rectal resection and 5 had complete endoscopic resection of their lesion. No carcinomas that were fully resected endoscopically have recurred (follow-up 13 months to 8years). The final patient had an extensive rectal cancer and was palliated for 2 months by ETAR. Twelve patients (8 men, 4 women) underwent ETAR for anastomotic strictures; successful treatment was achieved in 11. The one failure was in a Park’s pouch that was subsequently refashioned. Seventeen patients underwent 30 ETARs for palliation of nonresectable rectal adenocarcinoma. Successful palliation of symptoms was achieved in 13 patients and the remainder underwent colostomy formation.

One patient died of a myocardial infarction. There were two further complications (blood transfusion for postoperative bleeding, postoperative cerebrovascular accident).

Conclusions

Endoscopic transanal resection of tumor is safe and effective and offers successful palliation or definitive treatment of rectal lesions with low rates of death and complications when performed by a dedicated surgeon.

Rectal neoplasms, both benign and malignant, have traditionally been managed by radical open surgical procedures, including anterior and abdominoperineal resections, posterior proctectomies (Kraske’s approach), and the posterior transsphincteric York-Mason approach. 1 However, these are major surgical procedures with associated complications and may be unsuitable for elderly, frail patients and unnecessary if the purpose of the intervention is to resect early benign lesions or achieve palliative symptom control. 2–5 In recent years, local treatment procedures have been developed to manage benign lesions and offer palliation in nonresectable tumors where the risks of open surgery would be unjustifiable. 2,3,6

Endoscopic transanal resection of tumor (ETAR), using urologic resectoscopes, 2,7 is a local approach for either the palliation or the definitive treatment of rectal neoplasms or symptomatic control of anastomotic strictures without the risks of major surgery. The technique of ETAR is particularly useful when the lesion lies below the peritoneal reflection but not within reach of rectal examination 2 and has been used during a 10-year period by one surgeon at our specialized colorectal unit. The data presented are a retrospective audit of the results of this surgeon’s experience.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

A retrospective audit was undertaken to review the surgical outcome of 104 patients who underwent ETAR between 1989 and 1999.

All patients were under the care of one consultant surgeon at a specialized colorectal unit and were identified by using the consultant’s personal records cross-referenced with operating room logs. All patients undergoing ETAR for definitive treatment, for palliative resection, or in the management of anastomotic strictures were included. No patients were lost to follow-up.

As previously described elsewhere, 1,2,5,7,8 the procedure consists of inserting a 24F 30° urologic rectoscope into the rectum with the patient in the Trendelenburg lithotomy position. Metronidazole (500 mg) and cefuroxime (750 mg) are used as antibiotic prophylaxis; 1.5% glycine solution is used as irrigant. The loop-cutting electrode is used to resect the lesion without breaching the muscular wall of the rectum. The resection site is then sealed using a 26F Foley balloon catheter, which also allows the remaining fluid to drain. The catheters are removed the next day and the patient is allowed home once bowel action recommences.

Any small residual nodules or areas of recurrence can be subsequently fulgurated on an outpatient basis using the rigid or flexible sigmoidoscope. Large lesions are managed with further transanal resection or open surgery as required.

RESULTS

One hundred four patients underwent 158 procedures during the 10-year period. The results are categorized according to the pre-ETAR diagnoses in Table 1.

Table 1. PATIENTS UNDERGOING ETAR OVER A 10-YEAR PERIOD

ETAR, endoscopic transanal resection.

Adenomas

Seventy-five patients (44 men, 31 women; mean age 68.5 years [range 31–90]) underwent ETAR for a pre-ETAR diagnosis of benign rectal adenoma.

Confirmed Benign

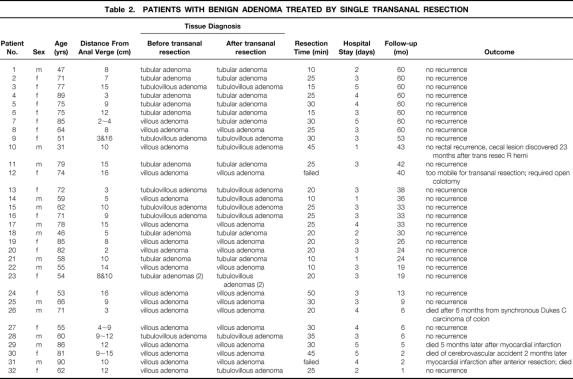

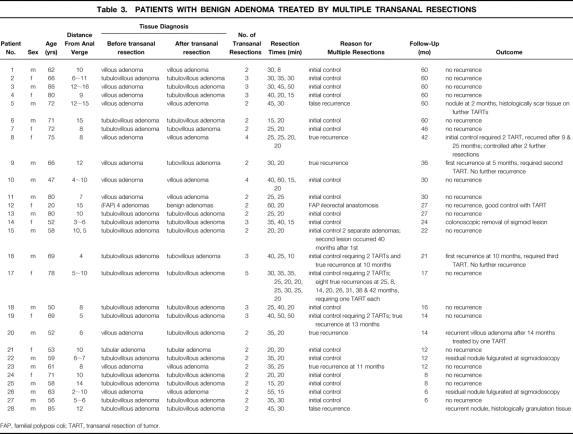

Sixty were confirmed as being benign on histologic examination and were managed as follows. Thirty-two patients (14 men, 18 women; mean age 67.6 years [range 31–90]) underwent a single ETAR (Table 2). The median distance of lesions from the anal verge was 10 cm (range 2–16) and the median resection time was 25 minutes (range 10–50). After a 3-day median hospital stay, patients were discharged. There were no recurrent adenomas and in no patients did adenocarcinoma develop during 5 years of follow-up. There were two technical failures because the lesions were highly mobile; these required open surgery. Twenty-eight patients (18 men, 10 women; mean age 64.68 years [range 47–86]) underwent a mean of three ETARs (range 2–10) (Table 3). Lesions ranged from 2 to 16 cm from the anal verge (mean 9). The reasons underlying the multiple resections included initial control (n = 21), false recurrence (n = 2), true recurrence (n = 7), secondary lesions (n = 1), and familial polyposis coli (n = 1). The median resection time for the first procedure was 30 minutes; all subsequent procedures took a median time of 20 minutes. The following outcomes were noted: no recurrence (n = 19), true recurrence (n = 4), nodules of granulation tissue (n = 4), and colonoscopic removal of sigmoid lesion (n = 1).

Table 2. PATIENTS WITH BENIGN ADENOMA TREATED BY SINGLE TRANSANAL RESECTION

Table 3. PATIENTS WITH BENIGN ADENOMA TREATED BY MULTIPLE TRANSANAL RESECTIONS

FAP, familial polyposi coli; TART, transanal resection of tumor.

Confirmed Malignant

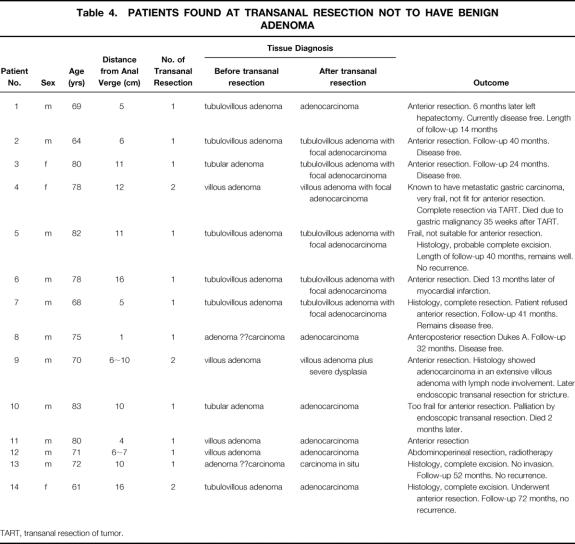

Fourteen patients (11 men, 3 women; mean age 73 years [range 61–83]) with a pre-ETAR diagnosis of benign rectal adenoma were confirmed on histology as having adenocarcinoma of the rectum (Table 4). After ETAR (11 patients had a single resection and 4 patients had two resections), 9 patients had open surgical procedures (7 anterior resections and 2 abdominoperineal resections) and 1 patient had palliation for extensive disease; in 4 patients the lesions had been completely excised. Lesions were 1 to 16 cm from the anal verge (mean 9 cm).

Table 4. PATIENTS FOUND AT TRANSANAL RESECTION NOT TO HAVE BENIGN ADENOMA

TART, transanal resection of tumor.

Carcinomas

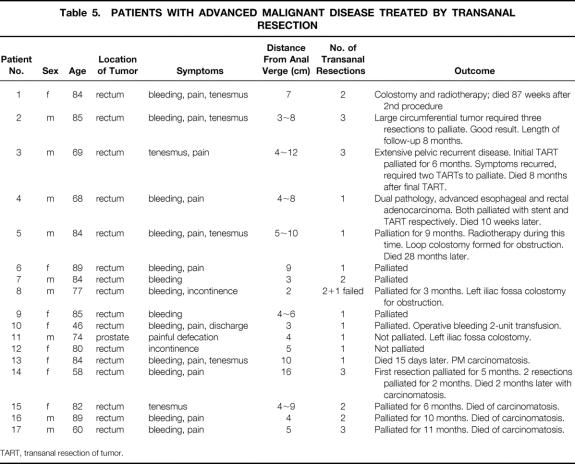

Seventeen patients (eight women, nine men; mean age 76 years [range 35–89]) were treated for advanced malignant disease (Table 5). Sixteen lesions were rectal and one prostatic, with a mean distance from the anal verge of 7 cm (range 2–12). The main presenting symptoms consisted of rectal bleeding, pain, and tenesmus or a combination of these symptoms. A total of 30 ETARs were undertaken; 13 patients were successfully palliated and 4 patients underwent defunctioning colostomies.

Table 5. PATIENTS WITH ADVANCED MALIGNANT DISEASE TREATED BY TRANSANAL RESECTION

TART, transanal resection of tumor.

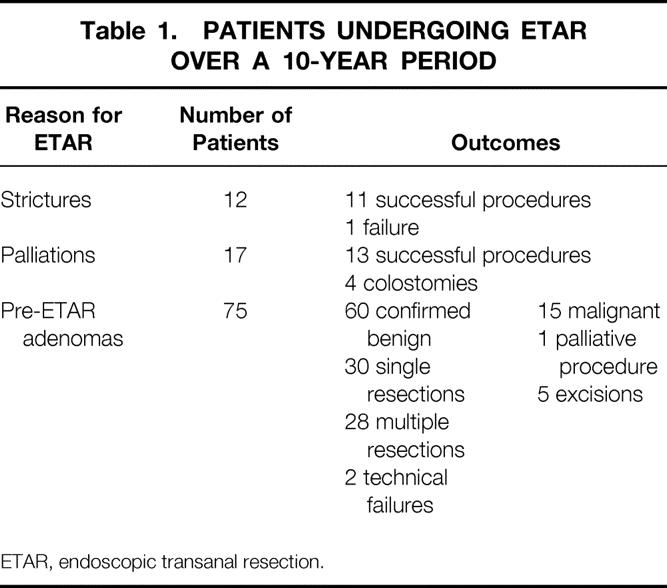

Anastomotic Strictures

Twelve patients (eight men, four women; mean age 58 years [range 23–80]) underwent ETAR for anastomotic strictures that developed after anterior resection in six patients, after reversal of Hartmann’s procedure in four patients, and after the formation of a Park’s pouch in the remaining two patients (Table 6). Nine patients had one resection and the remainder two, averaging 50 minutes and 45 minutes resection time, respectively. Lesions were 3 to 14 cm from the anal verge (mean 7.17). Eleven procedures were successful. The one failure involved an ileoanal Park’s pouch, which was subsequently refashioned.

Table 6. PATIENTS WITH ANASTOMOTIC STRICTURE TREATED BY TRANSANAL RESECTION

Complications

Two patients had postoperative complications from the total 158 procedures undertaken. One patient being palliated by ETAR for advanced malignancy required a two-unit blood transfusion for postoperative blood loss; the other patient suffered a cerebrovascular accident. The overall complication rate was 1.3% of ETAR procedures, or 1.9% of patients. The 30-day death rate was 1%: one patient died after a myocardial infarction.

DISCUSSION

Conventional surgical management of rectal lesions usually involves anterior or abdominoperineal resections of the rectum. These are major, invasive procedures with a recognized perioperative death rate of 21% to 38% when used solely for palliative purposes, 5 and they may not be tolerated by frail patients, particularly those with additional comorbidity. 2,4,5 Recovery may be slow, increasing the length of hospital stay, and there is no guarantee of good functional results. Therefore, interest is increasing in the development of local treatment options, and one such approach is ETAR, one of the first minimally invasive techniques in modern surgery. 9

The transanal approach to tumor resection was first documented in 1979 by Zinkin et al, 10 who successfully palliated six patients with low rectal carcinomas. Since then, few large series have been published that detail the uses and outcomes of ETAR, 1,2,5,7 but very encouraging results have been obtained. Our series is the second-largest published to date and is, to our knowledge, the only series specifically relating to a single surgeon’s experience and evaluating the use of ETAR in managing anastomotic strictures (it includes five cases previously published 11).

In this series, 71% of patients underwent ETAR for a preoperative diagnosis of benign rectal adenoma. The upper limit of distance between the tumor and the anal verge was 16 cm, a figure also cited in other series. 1 On 5-year follow-up there were no tumor recurrences and no progression into carcinoma, which challenges the view that local techniques have a high recurrence rate, cited as 10% to 32%. 1,5,12 The 0% death rate for ETAR in benign adenomas compares favorably to that of other series, in which a small death rate (1–3%) has been documented. 5,13

Although in four instances where small carcinomas arose in otherwise benign adenomas, ETAR was used as the sole definitive treatment, this was very much a compromise, because accurate staging of the disease using this technique is impossible. Each patient was offered a standard open resection, and each declined this offer. Although follow-up suggests that they happen to have been right, we would not advocate ETAR as the definitive treatment for malignancy in this way.

In inoperable carcinomas palliative resection can be performed to alleviate symptoms of rectal bleeding, pain, tenesmus, incontinence, and combinations thereof. Three quarters of these patients were successfully ameliorated, thus avoiding major surgical intervention (with its associated rates of death and complications); 23%, however, did require a colostomy. Various methods of palliating advanced rectal malignant disease have been used, including radiotherapy, cryotherapy, fulguration, electrocoagulation, and laser destruction, but they have well-established complications and are often suitable only for small lesions, so their use is limited. 2,5,7 The results of ETAR presented here support the data from other studies 1,7 that ETAR has a valuable role in the palliation of advanced malignant disease.

Another use of ETAR, which to our knowledge has been carried out only in our colorectal unit is the treatment of anastomotic strictures. This series comprises 12 patients with strictures, 50% of which were due to previous anterior resections. A 91% success rate was achieved; the one failure involved a Park’s pouch, which was subsequently refashioned. No complications were recorded.

Our series overall shows low rates of complications (1.9%) and death (1%). Only two complications were associated with the 158 procedures undertaken, and there was only one death. Death rates of 3% to 5% and complication rates of 19% have been reported elsewhere, 5,7 and complications include hemorrhage, perforation, sepsis, rectovaginal fistulas, strictures, and urinary retention. 5,7 Leakage of irrigation fluid from the anus may occur, but it has been shown that an adapted Lord’s dilator can overcome this problem. 14 “TUR syndrome,” originally described after transurethral resection of prostate, is characterized by cardiovascular and neurologic signs caused by electrolyte changes associated with the absorption of glycine; it may be considered a potential complication, but the risk is negligible, as shown by Boyle et al in 1997. 15

The use of ETAR is limited to small, low-lying tumors. More proximally located tumors, however, can be excised by other minimally invasive, local techniques. Indeed, Buess and Mentgues developed transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEMS) in 1984; in this procedure, a sigmoidoscope incorporating a binocular optical system and pressure-regulated insufflation enables the excision of rectal tumors located farther from the anal verge than is possible with ETAR. 16,17 Studies thus far have shown TEMS to be an effective local treatment strategy in tumor excision (because of good field visibility) with few complications. 16–22

The development of minimal-access surgery has enabled the implementation of local management strategies for rectal lesions. Our series has shown that ETAR is effective (no disease recurrence) and safe (minimal complications, one death) when carried out by a dedicated surgeon. Further, we have shown that ETAR achieves excellent symptom control in the palliation of advanced malignant disease and has a useful role in the management of anastomotic strictures. Our findings, in addition to those from other series, highlight the important role of local treatment options for rectal neoplasia and the need for further developments in this field.

Footnotes

Correspondence: Christopher D. Sutton, FRCS, Department of Surgery, Leicester General Hospital, Gwendolen Road, Leicester, LE5 4PW, England.

E-mail: chrisdsutton@msn.com

Accepted for publication September 3, 2001.

References

- 1.Stephenson BM, Ng KJ, Shandall AA, et al. Endoscopic transanal resection of large villous tumours of the rectum. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1992; 74: 54–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wetherall AP, Williams NMA, Kelly MJ. Endoscopic transanal resection in the management of patients with sessile rectal adenomas, anastomotic stricture and rectal cancer. Br J Surg 1993; 80: 788–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mentges B, Buess G, Effinger G, et al. Indications and results of local treatment of rectal cancer. Br J Surg 1997; 84: 348–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Savage AP, Reece-Smith H, Faber RG. Survival after preanal and abdominoperineal resection for rectal carcinoma. Br J Surg 1994; 81: 1482–1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dickinson AJ, Savage AP, Mortensen NJ, et al. Long-term survival after endoscopic transanal resection of rectal tumours. Br J Surg 1993; 80: 1401–1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mentges B, Buess G, Schafer D, et al. Local therapy of rectal tumors. Dis Colon Rectum 1996; 39: 886–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berry AR, Souter RG, Campbell, et al. Endoscopic transanal resection of rectal tumours: a preliminary report of its use. Br J Surg 1990; 77:134–137. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Kelly MJ. Use of the urological resectoscope in benign and malignant rectal lesions: review of 12 cases. J R Soc Med 1989; 82: 588–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buess G. Review. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM). J R Coll Surg Edinb 1993; 38: 239–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zinkin LD, Katz LD, Rosin JD. A method of palliation for obstructive carcinoma of the rectum. Surg Gynaecol Obstet 1979; 148: 427–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hunt TM, Kelly MJ. Endoscopic transanal resection (ETAR) of colorectal strictures in stapled anastomosis. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1994; 76: 121–122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saclarides T. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery. Surg Clin North Am 1997; 77: 229–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thompson JPS. Treatment of sessile villous and tubulovillous adenomas of the rectum. Experience of St Mark’s Hospital 1963–1972. Dis Colon Rectum 1977; 20: 67–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Courtney SP, Nankivell C, Davidson CM. Endoscopic transanal resection of rectal lesions: facilitation by adaptation of Lord’s dilator. J R Coll Surg Edinb 1991; 36: 249–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyle JR, Thompson MM, Lopez B, et al. TUR syndrome and endoscopic transanal resection: no evidence for a clinically important association in 38 procedures. Br J Surg 1997; 84: 831–833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith LE, K. ST, Saclarides T, et al. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery. Dis Colon Rectum 1996; 39:S79–84. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Steele RJC, Hershman MJ, Mortensen NJ, et al. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery: experience from three centres in the United Kingdom. Br J Surg 1996; 83: 207–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swanstrom LL, Smiley P, Zelko J, Cagle L. Video endoscopic transanal-rectal tumour excision. Am J Surg 1997; 173: 383–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saclarides TJ. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery, a single surgeon’s experience. Arch Surg 1998; 133: 595–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lezoche E, Guerrieri M, Paganini A, et al. Transanal endoscopic microsurgical excision of irradiated ans non-irradiated rectal cancer. Surg Laparosc Endosc 1998; 8: 249–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lezoche E, Guerrieri M, Paganini A, et al. Is transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) a valid treatment for rectal tumours? Surg Endosc 1996; 10: 736–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heintz A, Morschel M, Jungiger T. Comparison of results after transanal endoscopic microsurgery and radical resection for T1 carcinoma of the rectum. Surg Endosc 1998; 12: 1145–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]