Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the authors’ first 100 patients treated for achalasia by a minimally invasive approach.

Methods

Between November 1992 and February 2001, the authors performed 95 laparoscopic and 5 thoracoscopic Heller myotomies in 100 patients (age 49.5 ± 1.5 years) with manometrically confirmed achalasia. Before presentation, 51 patients had previous dilation, 23 had been treated with botulinum toxin (Botox), and 4 had undergone prior myotomy. Laparoscopic myotomy was performed by incising the distal 4 to 6 cm of esophageal musculature and extended 1 to 2 cm onto the cardia under endoscopic guidance. Fifteen patients underwent antireflux procedures.

Results

There were eight intraoperative perforations and only four conversions to open surgery. Follow-up is 10.8 ± 1 months; 75% of the patients have been followed up for at least 14 months. Outcomes assessed by patient questionnaires revealed satisfactory relief of dysphagia in 93 patients and “poor” relief in 7 patients. Postoperative heartburn symptoms were reported as “moderate to severe” in 14 patients and “none or mild” in 86 patients. Fourteen patients required postoperative procedures for continued symptoms of dysphagia after myotomy. Esophageal manometry studies revealed a decrease in lower esophageal sphincter pressure (LESP) from 37 ± 1 mm Hg to 14 ± 1 mm Hg. Patients with a decrease in LESP of more than 18 mm Hg and whose absolute postoperative LESP was 18 or less were more likely to have relief of dysphagia after surgery. Thirty-one patients who underwent Heller alone were studied with a 24-hour esophageal pH probe and had a median Johnson-DeMeester score of 10 (normal <22.0). Mean esophageal acid exposure time was 3 ± 0.6% (normal 4.2%). Symptoms did not correlate with esophageal acid exposure.

Conclusions

The results after minimally invasive treatment for achalasia are equivalent to historical outcomes with open techniques. Satisfactory outcomes occurred in 93% of patients. Patients whose postoperative LESP was less than 18 mm Hg reported the fewest symptoms. After myotomy, patients rarely have abnormal esophageal acid exposure, and the addition of an antireflux procedure is not required.

Heller first described cardiomyotomy for the treatment of achalasia in 1914 1 using an abdominal approach with an anterior and posterior esophageal myotomy. This approach was modified to a single myotomy by the Dutch surgeon Zaaijer in 1923, which is still in use today. 2 The thoracic approach was popularized by Ellis in 1958 3 and was the most commonly used surgical procedure in North America for achalasia for many years. This approach used a single cardiomyotomy performed through the left chest without an accompanying antireflux procedure.

Minimally invasive approaches were introduced in the past decade for many general surgical procedures. Initially, thoracoscopic myotomy was most commonly performed because of the influence of prevailing technique by thoracic surgeons. However, this technique was cumbersome due to the need for double-lumen endotracheal tubes, single lung ventilation, and postoperative chest tubes. Surgeons found the laparoscopic abdominal approach to the esophagus to be a simpler method. Laparoscopic cardiomyotomy was first reported in 1991 by Cuschieri et al. 4 Once laparoscopic myotomy was found to be technically feasible, it became the preferred surgical approach. 5 We report our first 100 patients treated with a minimally invasive approach.

METHODS

Ninety-five laparoscopic and five thoracoscopic Heller myotomies were performed in 100 consecutive patients (47 female patients, 53 male patients) at Vanderbilt University Medical Center by three surgeons between November 1992 and February 2001. Perioperative data on patients were prospectively collected and maintained in a database. All patients underwent preoperative manometry, endoscopy, and barium swallow study. Patients had the diagnosis of achalasia confirmed manometrically with simultaneous esophageal body contractions and a nonrelaxing lower esophageal sphincter (LES). Before presentation, 51 patients had undergone previous dilation, 23 had been treated with botulinum toxin (Botox), and 4 had undergone prior myotomy.

Patients were asked to return for a 24-hour pH study and manometry at least 6 weeks after the procedure as part of an institutional review board-approved study. Standard esophageal manometry was performed using a six-channel probe (Sandhill Scientific, Highlands Ranch, CO) using a pull-through technique. pH testing in the esophagus was performed using a standard two-channel probe placed 5 and 10 cm above the LES for 24 hours. Patients returning for study completed validated gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)-specific Quality of Life in Reflux and Dyspepsia (QOLRAD) or Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS) questionnaires after surgery. The QOLRAD is measured on a scale of 1 to 7, with 7 being the best score (no reflux symptoms). The GSRS is on a scale of 0 to 100, with the lowest score (0) reflecting no symptoms. All patients were also asked about subjective improvement in dysphagia and heartburn symptoms in the postoperative period.

Surgical Technique

Patients were placed supine on the operating room table in steep reverse Trendelenburg position. After an early patient had a postoperative pneumonia from aspiration at the induction of anesthesia, we asked the anesthesiologists to treat all patients as if they had a full stomach. Consequently, careful measures were taken to avoid aspiration of retained food contents in the esophagus. All patients received general endotracheal anesthesia for the procedure.

Using a Hasson technique, the abdomen was initially entered through a midline incision placed halfway between the umbilicus and the tip of the xiphoid process. A 30° laparoscope was introduced through this trocar to allow placement of the remaining 5-mm trocars under direct visualization. A self-retaining, table-mounted retractor placed through a 5-mm port in the right upper quadrant was used to elevate the lateral segment of the left lobe of the liver superiorly (without dividing the attachments of the left lateral segment) to expose the gastroesophageal junction. Two additional 5-mm working ports were placed in the right upper quadrant, and one was placed in the left upper quadrant.

The phrenoesophageal ligament was divided, exposing the anterior esophagus and cardia. Laparoscopic myotomy was performed by incising the distal 4 to 6 cm of esophageal musculature and extended 1 to 2 cm onto the gastric cardia using bipolar cautery scissors or an ultrasonic scalpel. Fifteen patients underwent a Dor fundoplication. Eight of these 15 fundoplications were performed to buttress an intraoperative esophageal perforation.

Intraoperative endoscopy was performed simultaneously with the myotomy to assess the adequacy of the myotomy and to detect mucosal perforations. The transillumination provided was very helpful in identifying the proper submuscular plane as well as in gauging how far to carry the myotomy onto the gastric cardia.

All patients were kept overnight and underwent a water-soluble contrast swallow on postoperative day 1 before initiation of a liquid diet. Most patients were discharged the same afternoon on a clear liquid diet.

Statistical Analysis

STATA Statistical software (College Station, TX) was used to perform statistical analyses. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests and paired t tests were used where appropriate. Chi-square analysis was used for nonpaired data. Spearman correlation was used to correlate pH data with subjective heartburn symptoms. Linear regression was also used to correlate reflux time with postoperative GERD scores. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. P ≤ .05 was used to determine statistical significance.

RESULTS

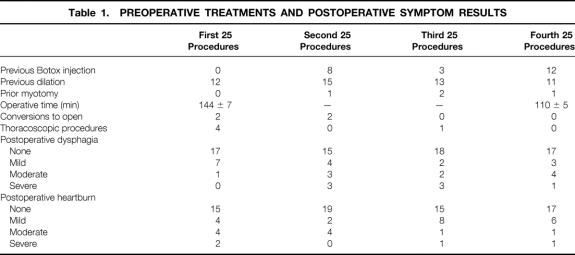

Patient ages ranged from 13 to 80 years (49.5 ± 1.5 years). The average hospital stay was 1.5 ± 0.1 days. Ninety-two patients who underwent laparoscopic procedure had a mean stay of 1.3 ± 0.1 days. The three patients who had the laparoscopic procedure converted to open stayed 5 ± 0.1 days. Patients who had a thoracoscopic procedure (n = 5) had a hospital stay of 3.2 ± 1.3 days. There were eight intraoperative perforations, six in the first 50 procedures and two in the last 50. Four conversions to an open procedure occurred within the first 50 patients; there were no conversions in the last 50 patients. Only two postoperative complications occurred: aspiration pneumonia developed in one patient after a laparoscopic procedure, and a lung abscess developed in another after a thoracoscopic myotomy. Both patients recovered and are doing well. No perioperative deaths occurred. Follow-up is 10.8 ± 1 months, with 75% of the patients being followed up for at least 14 months (median 14 months). Operative times improved significantly with experience. The first 20 procedures took 144 ± 7 minutes; the last 20 took 110 ± 5 minutes (P < .03;Table 1). No patient had a perforation revealed on the postoperative contrast swallow.

Table 1. PREOPERATIVE TREATMENTS AND POSTOPERATIVE SYMPTOM RESULTS

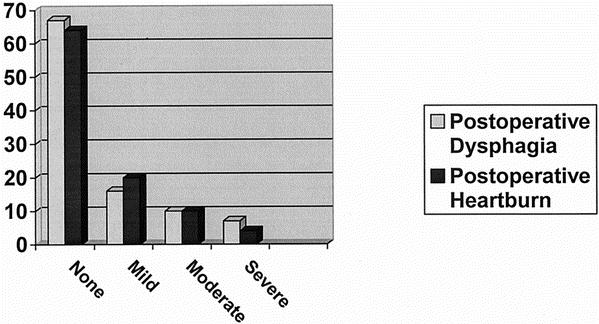

Outcomes assessed by patient questionnaires revealed “excellent” relief of dysphagia in 67 patients, “good” relief in 16, “fair” relief in 10, and a “poor” result in 7. Subjective postoperative heartburn symptoms revealed 66 patients having no heartburn, “mild” heartburn in 20, “moderate” in 10, and “severe” in 4 (Fig. 1). No correlation was found between symptom outcomes and preoperative treatment with Botox, dilation, or prior myotomy (see Table 1).

Figure 1. Most patients reported minimal postoperative heartburn and dysphagia.

Fourteen patients required one or more postoperative procedures for continued symptoms of dysphagia after myotomy. Eight patients underwent bougie dilation, three had pneumatic dilation, three had Botox injections, and three had redo myotomies. Two patients ultimately required total esophagectomy after failing to respond to two and three prior myotomies.

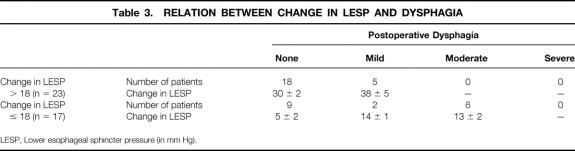

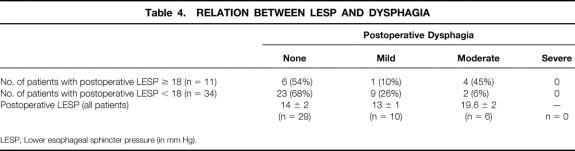

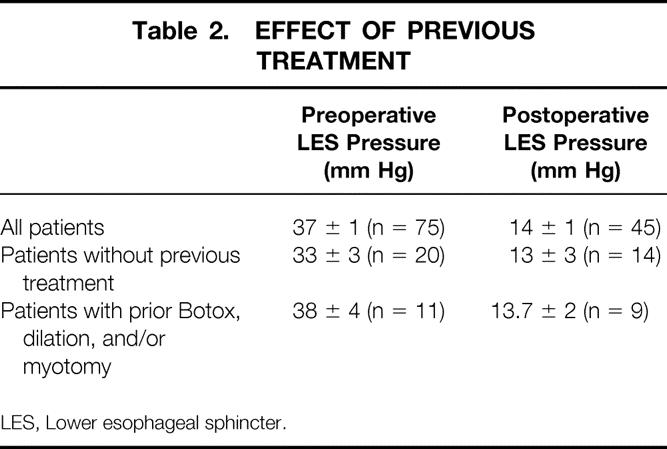

Preoperative esophageal manometry studies in 75 patients revealed a lower esophageal sphincter pressure (LESP) of 37 ± 1 mm Hg. In 15 patients, the manometry catheter could not be passed beyond the tight LES to perform the study. Forty-five patients studied with postoperative manometry had an LESP of 14 ± 1 mm Hg. The mean decrease in LESP for all patients was 22 ± 2 mm Hg. Patients who had received preoperative Botox or pneumatic dilatation had no difference in their preoperative and postoperative LESP measurements compared with patients who had no definitive preoperative treatment (Table 2). Patients with a decrease in LESP of more than 18 mm Hg were more likely to have no or only mild dysphagia after surgery compared with those who had a change in LESP of less than 18 mm Hg (Table 3). In addition, patients whose absolute postoperative LESP was 18 mm Hg or less were more likely to have good or excellent relief of dysphagia. Patients who had no or mild dysphagia after surgery had a postoperative LESP of less than 18, whereas patients with a fair or poor result had a mean LESP of 19.6 (Table 4).

Table 2. EFFECT OF PREVIOUS TREATMENT

LES, Lower esophageal sphincter.

Table 3. RELATION BETWEEN CHANGE IN LESP AND DYSPHAGIA

LESP, Lower esophageal sphincter pressure (in mm Hg).

Table 4. RELATION BETWEEN LESP AND DYSPHAGIA

LESP, Lower esophageal sphincter pressure (in mm Hg).

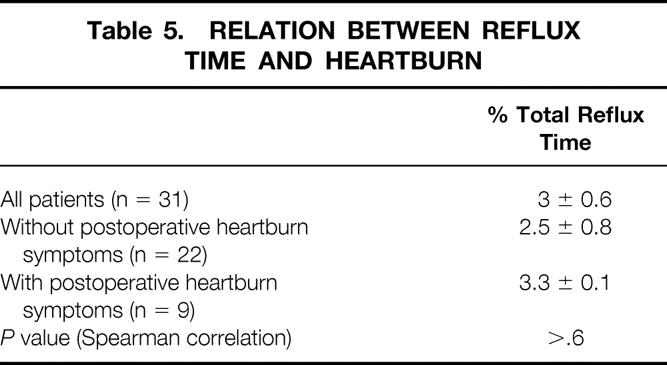

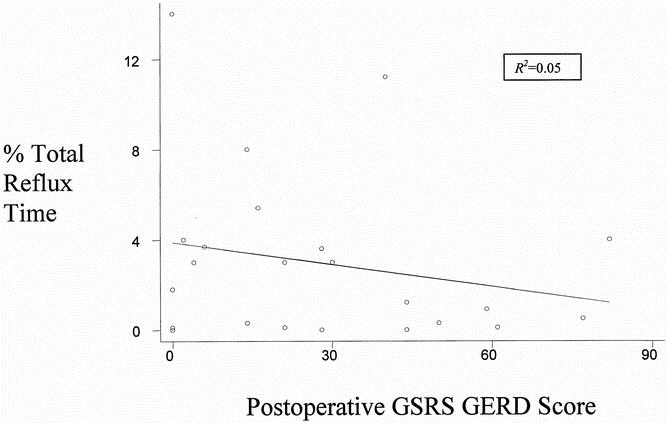

Thirty-one patients who did not have a fundoplication at the time of the procedure were studied after surgery with a 24-hour esophageal pH probe. Mean esophageal acid exposure time was 3 ± 0.6%. Patients without symptoms (n = 22) had 2.5 ± 0.8% total reflux time versus 3.3 ± 1% for those with symptoms (Table 5). Only four of the patients studied had abnormal total reflux time. Symptoms correlated poorly with esophageal acid exposure (R2 = 0.05 by regression analysis;Fig. 2).

Table 5. RELATION BETWEEN REFLUX TIME AND HEARTBURN

Figure 2. No correlation was seen between postoperative total percentage reflux time and postoperative gastroesophageal reflux disease score measured by the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS GERD).

Preoperative and postoperative GSRS GERD scores were available for 24 patients. Postoperative GERD scores decreased significantly compared with preoperative scores: 48 ± 1 to 27 ± 1 (P = .0004). Midway through the study, the GERD-related questionnaires used by our practice changed from the GSRS to the QOLRAD because the QOLRAD is shorter and easier to complete by patients and score by investigators. Therefore, patients early in the experience completed the GSRS and patients later in the experience completed the QOLRAD. Postoperative GERD scores were normal for most patients (n = 39, 30 ± 4), as were QOLRAD scores (n = 15, 6.2 ± 0.2).

DISCUSSION

This large single-institution series provides a unique perspective on the surgical treatment of achalasia. No other series reports as many patients with follow-up manometry and 24-hour pH results. This unique experience has given us insight into some of the controversial issues, and we will address them individually.

Laparoscopic Versus Thoracoscopic Approach

This question was answered very early in our experience, as it was in the experience of several surgeons performing cardiomyotomy with minimally invasive techniques in the early 1990s. The first four myotomies at Vanderbilt were performed through the left chest. We experienced difficulties that have been previously described by other authors and quickly adopted the transabdominal laparoscopic approach. Technically, the thoracic approach has been described as problematic because the surgeon cannot very precisely determine the exact length needed for the myotomy onto the cardia, and the surgeon is working orthogonal to the axis of the esophagus. 6 In addition, the thoracic approach requires a longer operative time: a double-lumen tube is needed, the procedure is performed in the lateral decubitus position, and chest drainage is required after surgery. 7 The laparoscopic approach requires no special intubation, positioning, or postoperative drainage, and it is a more ergonomic way to visualize and approach the esophagus parallel to its axis. As these problems were being realized, we began performing an increasing number of laparoscopic antireflux procedures, during which we observed how simply a significant amount of the mediastinal esophagus could be exposed. Thus, for subsequent procedures, the thoracoscopic approach was abandoned and the laparoscopic approach was adopted. Currently, most gastrointestinal surgeons prefer the laparoscopic approach. 6 Stewart et al. 8 also observed multiple advantages with the laparoscopic Heller myotomy compared with the thoracoscopic approach in a comparative retrospective review, noting a decreased operative time, a decreased rate of conversion to open surgery, and a shorter hospital stay. Patients approached through the abdomen also had better long-term outcomes, with less dysphagia and heartburn, which the authors attributed to the improved visualization provided by the laparoscopic approach. 8 An additional benefit of the transabdominal approach is that patients who are high anesthesia risks for the thoracic approach because of the need for single-lung ventilation now are potential candidates for a laparoscopic procedure.

The thoracoscopic approach, however, need not be completely abandoned, because in selected patients the thoracic approach may be beneficial. One patient did undergo thoracoscopic myotomy later in our series because that patient had undergone multiple abdominal operations, including a previous myotomy. The patient with a hostile abdomen or the patient in whom an abdominal myotomy has failed may be considered for a thoracoscopic approach.

Learning Curve

Most of the perforations in our series occurred in the first 50 procedures, with six perforations in the first 50 cases and only two in the last 50 cases, and all conversions to open procedure occurred in the first 50 procedures. Operative times decreased significantly in the last 20 procedures compared with the first 20, from 144 ± 7 minutes to 110 ± 5 minutes (P < .03). As with most advanced laparoscopic procedures, a substantial learning curve is associated with laparoscopic myotomy. We have not noticed a difference in outcome with this learning curve with respect to patient satisfaction or relief of dysphagia.

Technical Issues

Several technical issues have come to light as we have performed more myotomies. We find that minimal dissection of the esophagus is required to perform an adequate myotomy. There is no need to mobilize the entire esophagus and disrupt all of the posterior and lateral attachments of the esophagus and cardia: only the anterior phrenoesophageal fat pad needs to be incised in most patients to expose the anterior esophagus. This preserves the angle of His and may help minimize postoperative reflux. Once the distal anterior esophagus and proximal cardia are exposed, one can proceed to myotomy. We determine the length of the myotomy using intraoperative endoscopy rather than using an arbitrary length of incision on the esophagus and cardia. Our myotomy usually extends 4 to 6 cm up the esophagus and 1 to 2 cm onto the gastric cardia; however, with endoscopic assistance, we have found that some patients had a visually adequate myotomy with less.

We have observed that one of the most important predictors of a good outcome in terms of relief of dysphagia is adequate extension of the myotomy onto the gastric cardia. We assess adequacy both visually and mechanically. Visually, the gastroesophageal junction should appear patulous on intraoperative endoscopy. The ease with which the endoscope can be passed through the gastroesophageal junction is equally important. The use of intraoperative endoscopy has been similarly described by other groups to assess the adequacy of the myotomy and to avoid excessive myotomy onto the cardia. 9

Initially, we routinely performed a contrast study the morning after the procedure because we were concerned about missing occult perforations. We have abandoned this practice because none of these studies ever revealed a perforation. We selectively perform contrast studies only if the patient exhibits an unusual amount of postoperative pain, tachycardia, or fever.

Impact of Prior Treatment

Several authors have commented on the increased difficulty in performing a surgical myotomy in a patient who has had previous nonoperative treatment for achalasia, such as Botox injection or pneumatic dilation. 10 Pneumatic dilation has been identified as a specific risk factor for complication with laparoscopic Heller myotomy in a previous report. 10 In that report, 28% of patients with previous dilation suffered an intraoperative mucosal perforation, whereas none of the patients not previously treated had perforations.

In our series of 100 patients, only eight perforations occurred. No statistically significant correlation was found with previous procedures. Five of the eight patients had undergone a previous therapeutic procedure (Botox injection, pneumatic dilation, or myotomy) for achalasia. Subjectively, we have noticed that the gastroesophageal junction is much more scarred in patients who have been dilated or treated with Botox, resulting in a much more difficult dissection in the submuscular plane over the mucosa. However, the incidence of intraoperative perforation is low if the procedure is performed carefully. This observation has been described by others. 11

Predictors of Outcome

The most important outcome for the patient with achalasia is relief of dysphagia. We did not find that previous treatment with Botox or dilation had any effect on relief of dysphagia (see Table 2). There were no learning curve issues with regard to dysphagia relief: the patients early in our series had as effective relief as those later in the series (see Table 1). We did find that a decrease in the postoperative LESP of 18 mm Hg correlated with better relief of dysphagia (see Table 3), which probably means that patients with a high LESP after surgery had an incomplete myotomy or that patients with low preoperative LESP did not get as much relief, because their relative decrease in outflow obstruction was less. Patients with a postoperative LESP of more than 18 mm Hg had more postoperative dysphagia (see Table 4).

Patients whose postoperative absolute LESP was less than 18 also reported much better relief of dysphagia than those whose LESP was greater than 18. Again, this indicates that those with a higher postoperative LESP received an incomplete myotomy (see Table 4).

Addition of an Antireflux Procedure

The addition of an antireflux procedure to a Heller myotomy is one of the most controversial topics surrounding surgical treatment for achalasia, but there are few objective data to report. Follow-up pH studies were performed in 10 patients who underwent thoracoscopic cardiomyotomy, and 6 of them had abnormal pH results. 12 Based on small series such as this one, several surgeons believe that an antireflux procedure should be added to the Heller myotomy. 13 Most agree that a complete 360° fundoplication should not be added to a myotomy for achalasia because of the risk of persistent postoperative dysphagia. The two most common antireflux procedures added to the Heller myotomy are the Toupet and Dor partial fundoplications. Proponents of the Toupet fundoplication contend that it helps to hold the cardiomyotomy open and is a better antireflux valve than the Dor fundoplication, 14 and patients have reported few symptoms of heartburn after surgery. 14,15 One study with objective pH data in the follow-up period showed no pathologic reflux in nine of nine patients with Heller plus Toupet, and positive reflux in two of three patients with Heller alone. 16

Some prefer the Dor fundoplication because it does not angulate the distal esophagus like the Toupet, and it does not require the extensive dissection at the gastroesophageal junction. In a large series from Italy, 81 of 206 patients underwent 24-hour pH monitoring after surgery, and 8.6% of patients had abnormal acid exposure. The investigators believed that four of the seven patients with pathologic reflux had the reflux as a result of circumferential dissection of the esophagus at the time of surgery. 17 Anselmino et al. 18 also found pathologic reflux in only 2 of 35 patients studied 1 year after Heller with Dor. Other groups have also reported good symptomatic outcomes with the Heller plus Dor. 5

At Vanderbilt, we have previously reported that an antireflux procedure should not be added to a Heller myotomy. 19,20 We believe that all antireflux procedures, whether partial or complete, add some resistance to the flow of food, thereby reducing the effectiveness of the procedure. If the procedure is performed with minimal dissection of the esophagus and gastric cardia, most of the esophageal attachments remain intact, allowing preservation of the patient’s natural antireflux mechanisms. Patients have minimal reflux with Heller alone in our experience, with a mean acid exposure time of only 3.3 ± 1% in the 31 patients studied (normal <4.2%). Only four (12.9%) of these patients had a total reflux time in a 24-hour period greater than 4.2%. Subjectively, 86% of patients reported “no” or “mild” symptoms of heartburn after surgery. Bloomston and Serafini 9 used a similar technique in a series of 100 patients and noted similar symptomatic results. None of the patients in our series or in any other series reported has gone on to develop a reflux-induced stricture of the esophagus.

We believe that adding an antireflux procedure carries several potential disadvantages for the patient. The effectiveness of the procedure may be compromised by adding an antireflux procedure because the fundoplication by design adds a nonrelaxing artificial LES that may be a problem for patients with achalasia because they have a nonperistaltic esophagus. In a group of patients undergoing Toupet with Heller, patients had a mean postoperative LESP of 22. 13 In our study, patients with Heller alone had a mean postoperative LESP of only 14. Although some of these differences in postoperative LESP may be related to the measurement technique, we believe that a lower LESP contributes to better relief of dysphagia. Others have also noted a postoperative LESP of only 12 after Heller alone and minimal postoperative reflux. 21 These low LESPs are consistent with our finding that the patients with the best symptomatic relief of dysphagia are those who had a postoperative LESP of 18 mm Hg or less.

The addition of an antireflux procedure also adds to the procedure time. Our mean operative time in the last 20 patients was only 110 minutes, whereas those who use an antireflux procedure report times of 192 minutes or more. 13,15

A corollary to whether an antireflux procedure is indicated is whether patient symptoms correlate with the presence of true pathologic reflux. Our group and others have found that patient symptoms of heartburn have no correlation to the presence of pathologic reflux. 6,13 It has been found that patients with achalasia have decreased mechano- and chemosensitivity compared with normal volunteers, showing that patients with achalasia do not sense acid reflux like normals. The investigators suggest that neuropathic defects in achalasia may manifest themselves in visceral sensory as well as motor dysfunction. 22 Perhaps all patients undergoing Heller myotomy should undergo a 24-hour pH study after surgery to assess for pathologic reflux so that those with pathologic reflux can be treated medically. Because these patients do not sense acid reflux normally, it should be noted the subjective symptoms of “heartburn” after surgery should be evaluated with endoscopy or pH monitoring rather than empirically treated with proton pump inhibitors. True postoperative acid reflux can be treated medically, but dysphagia from an antireflux procedure cannot.

Treatments for Achalasia

Multiple treatments for achalasia exist, including pneumatic dilatation, Botox injection, or surgical myotomy. Because of the rarity of achalasia, no controlled study comparing the different treatments has enough power to make conclusive remarks on which is the most efficacious treatment. However, several small series exist. Botulinum toxin injection, one of the least morbid treatments, has been increasing in popularity as a treatment during the past several years because of its simplicity and safety, even though it is very poor as a long-term treatment for achalasia. Two randomized trials 23,24 comparing Botox injection and pneumatic dilatation revealed high relapse rates with Botox. In one of these studies, a single Botox injection produced remission in only 15% of patients at 1 year; after two injections, however, 60% of the 20 patients had an effect at 1 year of follow-up. Pneumatic dilatation had much more efficacy: 52% of patients were asymptomatic after one treatment. Those with relapse were treated a second time, achieving 100% remission. 23 Another randomized study had similar results, with 70% remission in the dilatation group and 32% remission in the Botox group at 1 year. 24

Historically, dilation has been the most popular way to treat achalasia. Most recent therapy involves pneumatic dilation through rapid dilation of a polyethylene balloon in the distal esophagus to bluntly rupture the muscular layers of the esophagus. The success rate was at least 50% with one treatment and almost doubled with two treatments. 23–25 The problem with pneumatic dilation is that although it can be very effective (especially with repeated treatments), the procedure is associated with a 2% to 7% perforation rate and a death rate of 1% to 2%. 25,26 Surgical myotomy, in contrast, has not been associated with any deaths in our series or in others. 13,14 Another factor in considering treating achalasia with pneumatic dilation is that the outcomes after pneumatic dilation appear to be age-related: patients younger than 40 years of age did not do as well as older patients. 27 Laparoscopic myotomy in our series has a very low complication rate (2%), which is lower than virtually any series of dilated patients.

To find long-term data on pneumatic dilation, we must go to the prelaparoscopic era, where large studies compared surgery with pneumatic dilatation. In 1979, the Mayo Clinic reported on 468 patients followed up for 6.5 years, comparing pneumatic dilation with thoracic myotomy. 28 Sixty-five percent of the patients in the dilation group were asymptomatic at follow-up, whereas 85% of the surgical patients were free of dysphagia at follow-up. The only prospective randomized trial comparing pneumatic dilation and surgery revealed symptomatic relief in 95% of surgical patients versus 65% in dilated patients. 29 Although these studies predate the laparoscopic era, laparoscopic myotomy has been as effective as open myotomy without the associated complications in short-term follow-up. There are as yet no long-term studies of the durability of relief of dysphagia with laparoscopic myotomy, and this will be essential if we are to recommend this as the standard treatment for achalasia.

Based on these results and our own experience, we believe that surgical cardiomyotomy should be the first line of therapy for all patients with achalasia who are acceptable candidates for general anesthesia. Carefully selected patients should have excellent long-term outcomes with few complications.

CONCLUSIONS

Laparoscopic Heller myotomy without an antireflux procedure is a safe and effective treatment for achalasia, with excellent symptomatic relief of dysphagia in most patients and minimal heartburn. There is a small learning curve to this procedure, but with close attention to technical detail, laparoscopic cardiomyotomy can be performed with minimal complications and no deaths. Surgical therapy should be the first line of treatment for patients with achalasia, because laparoscopic Heller myotomy has been shown to have lower rates of death and complications than dilatation. The addition of an antireflux procedure remains controversial, and our series does not effectively answer the question. We believe that the complications added by performing a partial fundoplication are unnecessary. We are conducting a randomized controlled trial to compare the efficacy of performing a Dor fundoplication with a Heller myotomy to see whether this results in decreased objective acid reflux compared with a Heller myotomy alone without increasing postoperative dysphagia. Trials such as this one are necessary to determine whether an antireflux procedure is necessary in these patients.

Discussion

DR. HENRY L. LAWS (Birmingham, AL): I would like to thank Dr. Sharp for providing me with a copy of this manuscript well in advance of the meeting.

His series of 100 patients managed by minimally invasive techniques represents an enormous experience. I am familiar with several surgeons who have treated more than 1,000 patients with gastroesophageal reflux, but very few in the United States who have managed 100 patients with achalasia.

Only four operations required conversion to an open procedure, all in the first 50 patients. Fifteen percent received an added Dor antireflux procedure, and 31 unwrapped patients were studied postoperatively for pathologic gastroesophageal reflux. We noticed most studies were dramatically normal. There were no postoperative deaths. Eighty-three percent of patients experienced an excellent or good result. In the follow-up, symptomatic reflux was not a great problem.

We have been familiar with the work of Dr. Sharp and his colleagues for several years and have copied them in the utilization of endoscopic, intraesophageal monitoring of the completeness of the myotomy and in not adding an antireflux component to the procedure. We are strong advocates of leaving the esophagus in its bed, using intraesophageal surveillance for completeness, adding no Dor or Toupet. It is our practice to use five 5-mm cannulas in addition to the camera port; one for the liver retractor, two for the surgeon’s hands, and two for the assistant’s hands. Since we were able to check at the time of operation and endoscopy for leakage, we do not routinely perform a Gastrografin swallow on postoperative day 1.

I would commend this article to everyone in the audience. In the discussion the authors address the common questions and conundrums in the management of patients with achalasia, answering each based on their experience.

I would like to ask one additional question of Dr. Sharp. How do you handle those individuals with a truly huge megaesophagus which, unfortunately, all of us will encounter occasionally?

DR. BRUCE D. SCHIRMER (Charlottesville, VA): I also wish to congratulate the authors on an excellent presentation and on these outstanding results in the use of the laparoscopic approach to treat achalasia. The manuscript, I can assure you, is of the same high quality as the presentation.

Dr. Sharp and his colleagues have clearly shown that this approach is associated with excellent outcomes in terms of subjective relief of dysphagia, objective decrease in lower esophageal sphincter pressure, with a concurrent subjectively low incidence of reflux symptoms and a clearly objectively low incidence of measured reflux. I would emphasize to the audience, as Dr. Laws has also, that there are two important aspects of the procedure which we have also found to be essential. The first is that minimal esophageal dissection or mobilization is needed and is actually contraindicated; and the second is that intraoperative endoscopy is really essential to monitor the extent of the myotomy and to look for perforations. I have three questions for the authors.

Dr. Sharp, of the patients who had LES pressure decreases less than 18 and as a whole had a higher dysphagia rate, there were nine patients in the group who had no dysphagia, and they had only an average LES pressure decrease of 5, while there were six patients who were labeled as having moderate dysphagia, and they had an average LES decrease in pressure of 13. This difference in data seems a little bit illogical, and I wonder if you could give us an explanation as to that.

The second question is that it remains unclear to me, having read your manuscript, as to your thoughts on redo myotomies. You seemed to have good results in treating several failed myotomies not done previously by you, but of your 14 patients requiring further treatments for persistent dysphagia only 3 had another myotomy and 2 went on to require esophagectomy. Do you recommend a repeat myotomy if dysphagia persists, and under what circumstances?

Third, your data seemed fairly convincing that an antireflux operation is not needed as part of this procedure. Why, then, are you now conducting a prospective, randomized trial to look at the addition of a Dor fundoplication to a laparoscopic myotomy?

I wish to thank the authors for asking me to comment on their paper and the Association for the privilege of doing so.

DR. C. DANIEL SMITH (Atlanta, GA): As an invited guest, I appreciate the opportunity to have the floor to ask Dr. Sharp a couple of questions. I’m from Emory in Atlanta and we, too, have had some experience with this operation and continue to include an antireflux procedure with it. I have several questions related to that.

Number one, Dr. Sharp has mentioned that the Dor fundoplication was performed in this series to buttress the perforation. I am not sure that qualifies in their application as an antireflux procedure. Could he comment on the difference between the Dor and the Toupet as an antireflux procedure? Many of us continue to perform the Toupet, feeling that it is the better of the antireflux procedures to perform with a Heller myotomy.

My second question has to do with management of the hiatal defect that is created after exposing 6 cm of proximal esophagus on which to perform a myotomy. Without a posterior dissection, obviously you can’t do anything about a hiatal defect. Could you comment on whether you perform crural closure or any type of procedure to manage the hiatal defect that accompanies your procedure?

Finally, to expand a little bit on Dr. Schirmer’s comment about failures, 17 of your patients underwent further procedures for persistent dysphagia, yet you quoted a 4% failure rate. Can you comment on the 17% who went on to further procedures for dysphagia, but only a 4% failure rate?

DR. KENNETH W. SHARP (Nashville, TN): Henry, thank you for your kind comments. How do we handle patients with a megaesophagus? And the answer to that is: No differently. We have found sometimes those are a challenging cut to make. Sometimes the esophagus is very angulated. But we have been able to manage most of those patients in exactly the same manner as the others.

Dr. Schirmer, the patients who had less relief of their dysphagia and who had minimal change in their LES pressure were usually patients who had had a low preoperative LES pressure and oftentimes were patients who have had previous myotomies or previous dilatations. Those patients don’t have as much change in the outflow resistance of their esophageal emptying, and I think their subjective symptoms of dysphagia are not improved as much.

You also asked about my opinion on the redo myotomies. Well, one of the things I have learned as I have reviewed all this data are as I now look at the pressures in the patients as we restudy them, for patients who have persistent complaints of dysphagia and if their postoperative LES pressure is greater than 20, I will strongly consider a redo myotomy. If their pressure is 10, 15, 16 mm Hg after their myotomy and they still have dysphagia, we are unlikely to improve them with another cut, as we are unlikely to lower that LES pressure much more. So I think we have learned a little bit by that.

Why are we doing a randomized study? Well, as Dr. Smith alluded to, there is a lot of debate in this field over, one, should we do an antireflux procedure, and, two, if we are going to do one, what should we do? This may not answer the question of do a Heller versus Heller plus Dor, but at least it is a step. It is going to be difficult to accrue patients here. I firmly believe the differences will be subtle, and we are probably going to have to enroll everybody with achalasia in the country to answer this question. So I am not real optimistic about developing a big difference here.

Your questions are very good. Is a Dor an antireflux procedure? If you read some of the Australian literature, they do this open as an antireflux procedure with decent results. I don’t consider it much of an antireflux procedure. But I don’t think you can do a good antireflux procedure with somebody who has no peristalsis and expect them to be able to swallow.

There is a limited amount of data that would tell us in a few small series that patients who have a Toupet fundoplication after a Heller myotomy have an increased rate of dysphagia compared to our series. I can’t answer that directly. I would certainly agree, I think a Toupet is a better operation than a Dor. But I don’t think a Toupet is a very good operation to begin with.

Second, management of the hiatal defect. I probably should say we forgot to close it, but we felt that was not necessary. We have not done any hiatal closures in these patients. It does look pretty impressive to see that big anterior defect. I am waiting to find a piece of colon up in there one day, but I haven’t yet.

Number three, patients with failed procedures. Seventeen percent of our patients have had investigation and further procedures for dysphagia. Many patients continue to have dysphagia. And I think many of these are the patients who had low preoperative LES pressures. They just don’t get as much relief as the ones with the high LES pressures preoperatively.

Many of these procedures postoperatively aren’t done under our control. I probably would not have dilated some of these patients that were dilated, and many of these were bougie dilatations done by an endoscopist who just thought, “Well, let’s dilate them and see if they get any better postoperatively.”

Our esophagectomies have been in patients who have failed two and three previous myotomies, so we have given them a pretty good old college try before we have gone to esophagectomy. One was my own series and one was a patient from Memphis who had had two previous failed myotomies.

Footnotes

Presented at the 113th Annual Session of the Southern Surgical Association, December 3–5, 2001, Hot Springs, Virginia.

Correspondence: Kenneth W. Sharp, MD, D5203, MCN, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN 37232.

E-mail: ken.sharp@mcmail.vanderbilt.edu

Accepted for publication December 2001.

References

- 1.Heller E. Extramukose kerkioplastic beim chronischen Kardiospasmus mit Dilatation des Oesophagus Mitt Grenzgeb. Med Chir 1914; 27: 141–149. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zaaijer JH. Cardiospasm in the aged. Ann Surg 1923; 77: 615–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ellis FH, Jr., Olsen AM, Holman CB, et al. Surgical treatment of cardiospasm (achalasia of the esophagus): consideration of aspects of esophagomyotomy. JAMA 1958; 166: 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimi S, Nathanson LK, Cushieri A. Laparoscopic cardiomyotomy for achalasia. J R Coll Surg Edinb 1991; 36: 152–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patti MG, Pellegrini CA, Horgan S, et al. Minimally invasive surgery for achalasia: An 8-year experience with 168 patients. Ann Surg 1999; 230: 587–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hunter JG, Richardson WS. Surgical management of achalasia. Surg Clin North Am 1997; 77: 993–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cade R. Heller’s myotomy: thoracoscopic or laparoscopic. Dis Esoph 2000; 13: 279–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stewart KC, Finley RJ, Clifton JC, et al. Thoracoscopic versus laparoscopic modified Heller Myotomy for achalasia: efficacy and safety in 87 patients. J Am Coll Surg 1999; 189: 164–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bloomston M, Serafini F. Routine fundoplication is not necessary with laparoscopic Heller myotomy and intraoperative endoscopy [abstract]. Gastroenterology 2001; 120: 489. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morino M, Rebecchi F, Festa V, et al. Preoperative pneumatic dilatation represents a risk factor for laparoscopic Heller myotomy. Surg Endosc 1997; 11: 359–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ponce J, Juan M, Garrigues V, et al. Efficacy and safety of cardiomyotomy in patients with achalasia after failure of pneumatic dilatation. Dig Dis Sci 1999; 44: 2277–2282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pellegrini CA. Impact and evolution of minimally invasive techniques in the treatment of achalasia. Surg Endosc 1995; 9: 286–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swanstrom LL, Pennings J. Laparoscopic esophagomyotomy for achalasia. Surg Endosc 1999; 9: 286–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hunter JG, Trus TL, Branum GD, et al. Laparoscopic Heller myotomy and fundoplication for achalasia. Ann Surg 1997; 225: 655–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vogt D, Curet M, Pitcher D, et al. Successful treatment of esophageal achalasia with laparoscopic Heller myotomy and Toupet fundoplication. Am J Surg 1997; 174: 709–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swanstrom LL, Pennings J. Laparoscopic esophagomyotomy for achalasia. Surg Endosc 1995; 9: 286–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonavina L, Nosadini A, Bardini R, et al. Primary treatment of esophageal achalasia. Arch Surg 1992; 127: 222–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anselmino M, Zaninotto G, Constantini M, et al. One-year follow-up after laparoscopic Heller-Dor operation for esophageal achalasia. Surg Endosc 1997; 11: 3–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang PC, Sharp KW, Holzman MD, et al. The outcome of laparoscopic Heller myotomy without antireflux procedure in patients with achalasia. Am Surg 1998; 64: 515–521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richards WO, Clements RH, Wang PC, et al. Prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux after laparoscopic Heller myotomy. Surg Endosc 1999; 13: 1010–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kjellin AP, Granqvist S, Ramel S. Laparoscopic myotomy without fundoplication in patients with achalasia. Eur J Surg 1999; 165: 1162–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brackbill SP, Guoxiang S, Hirano I. Impaired esophageal mechanosensitivity and chemosensitivity in achalasia [abstract]. Gastroenterology 2001; 120 (suppl): 644. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mikaeli J, Fazel A, Montazeri F, et al. Randomized controlled trial comparing botulinum toxin injection to pneumatic dilation for the treatment of achalasia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2001; 15: 1389–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vaezi MF, Richter JE. Current therapies for achalasia: comparison and efficacy. J Clin Gastroenterol 1998; 27: 21–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferguson MK. Achalasia. Current evaluation and therapy. Ann Thorac Surg 1991; 52: 336–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abid S, Champion G, Richter JE, et al. Treatment of achalasia: The best of both worlds. Am J Gastroenterol 1994; 89: 979–985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parkman HP, Reynolds JC, Ouyang A, et al. Pneumatic dilatation or esophagomyotomy treatment for idiopathic achalasia: Clinical outcomes and cost analysis. Dig Dis Sci 1993; 38: 75–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okike N, Payne WS, Neufeld DM, et al. Esophagomyotomy versus forceful dilation for achalasia of the esophagus: Results in 899 patients. Ann Thorac Surg 1979; 28: 119–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Csendes A, Braghetto I, Henriques A, et al. Late results of prospective randomized study comparing forceful dilation and esophagomyotomy in patients with achalasia. Gut 1989; 30: 299–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]