Abstract

Objective

To determine the clinical features, natural history, and role of surgery for gastrointestinal manifestations of the multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (MEN 2) syndromes.

Summary Background Data

The MEN 2 syndromes are characterized by medullary thyroid carcinoma and other endocrinopathies. In addition, some patients with MEN 2A develop Hirschsprung’s disease (HD), and all patients with MEN 2B have intestinal neuromas and megacolon that can cause significant gastrointestinal problems.

Methods

From 83 families with MEN 2A, eight patients with HD were identified (MEN 2A-HD). These and all patients with MEN 2B followed at the authors’ institution (n = 53) were sent questionnaires to describe the onset and type of gastrointestinal symptoms and treatment they had before the diagnosis of MEN 2. Records of all patients responding were reviewed, including radiographic imaging, histology, surgical records, and genetic testing.

Results

Thirty-six of the 61 patients (59%) responded (MEN 2A = 8, MEN 2B = 28) to the questionnaires. All patients with MEN 2A-HD were operated on for HD 2 to 63 years before being diagnosed with MEN 2. All patients responding were underweight as infants and had symptoms of abdominal pain, distention, and constipation. Eighty-eight percent had hematochezia, 63% had emesis, and 33% had intermittent diarrhea before surgery. All patients with MEN 2A-HD had rectal biopsies with a diverting colostomy as the initial surgical procedure. This was followed by a colostomy takedown and pull-through procedure at a later interval. Ninety-three percent of patients with MEN 2B had gastrointestinal symptoms 1 to 24 years before the diagnosis of MEN 2. Symptoms included flatulence (86%), abdominal distention or being underweight as a child (64%), abdominal pain (54%), constipation or diarrhea (43%), difficulty swallowing (39%), and vomiting (14%). Seventy-one percent of patients with MEN-2B with gastrointestinal symptoms had radiographic imaging, 32% were admitted to the hospital, and 29% underwent surgery.

Conclusions

Patients with MEN 2A-HD had a typical HD presentation and always required surgery. Patients with MEN 2B have significant gastrointestinal symptoms, but less than a third had surgical intervention. Understanding the clinical course and differences in these patients will improve clinical management.

The multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) type 2 syndromes include MEN 2A, MEN 2B, and familial, non-MEN medullary thyroid carcinoma. These are autosomal dominant inherited syndromes that are caused by germline mutations in the RET protooncogene. The hallmark of these syndromes is the development of medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC), which is multifocal and bilateral and usually occurs at a young age. MTC occurs in almost all patients with the MEN 2 syndromes. Other features are variably expressed. In MEN 2A, pheochromocytomas develop in approximately 42% of affected patients; they may also be multifocal and bilateral, and are associated with adrenal medullary hyperplasia. Hyperparathyroidism occurs in 25% to 35% of patients. Hirschsprung’s disease (HD) is infrequently associated with MEN 2A. 1–3 This disease is characterized by absence of autonomic ganglion cells within the distal colonic parasympathetic plexus, resulting in obstruction and megacolon.

The co-occurrence of MEN 2A and HD (MEN 2A-HD) is associated with mutations in codon 609, 618, or 620 of the RET protooncogene. 4–8 Most patients with these RET mutations have MEN 2A or familial MTC and do not develop HD. The biologic basis for the development of HD in some patients with MEN 2A is not known.

In MEN 2B, pheochromocytomas develop in 40% to 50% of patients, and all patients have neural gangliomas, particularly in the mucosa of the digestive tract, conjunctiva, lips, and tongue. Patients with MEN 2B also have skeletal abnormalities and markedly enlarged peripheral nerves but do not develop hyperparathyroidism. MTC in these patients develops at a very young age (infancy) and appears to be the most aggressive form of hereditary MTC, although its aggressiveness may be more related to the extremely early age of onset rather than the biologic virulence of the tumor. All patients with MEN 2B have megacolon.

Most patients with MEN 2B and those with MEN 2A-HD have gastrointestinal symptoms as infants, often before the development of MTC and other endocrine disorders. Many of these patients require surgery or medical treatment. 5–11 The goal of this study is to describe the clinical features and treatment of gastrointestinal problems in a large number of patients with MEN 2B and MEN 2A-HD followed up at our institution. Most patients with MEN 2A-HD had colostomy and pull-through procedures at a very young age, whereas only a few patients with MEN 2B and megacolon had surgery for their gastrointestinal disease. Surgeons should recognize the possibility of MEN 2 in patients, especially infants and children, who present with HD or megacolon.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Records of all 83 MEN 2A kindreds followed up at Washington University School of Medicine and the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center were reviewed to determine which patients had pathologic evidence of HD (n = 8). After approval from the institutional review board and human studies committee, questionnaires were sent to the eight patients with MEN 2A-HD and to 53 patients with MEN 2B followed up at this institution. Patients were questioned about clinical symptoms including the age of presentation, type of initial gastrointestinal symptoms, and age of diagnosis of MEN. In addition, the questionnaires documented any medications, radiographic examinations, hospital admissions, and surgical procedures related to gastrointestinal symptoms.

All responses were objectively evaluated and categorized. Genetic testing was performed in all patients. Objective data from the same category used in comparison between patients with MEN-2A and those with MEN 2B were tested for significance using the Fisher exact test, with significance defined at P ≤ .05.

All patients in this study were asked to describe the types of gastrointestinal symptoms or problems they experienced, including abdominal pain, distention, flatulence, dysphagia, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, and hematochezia, and whether they were underweight as children. All questionnaires were completed by patients and/or their parents regarding symptoms present in early childhood and infancy. Patients also reported the type of medical management, gastrointestinal radiographic studies, and hospital admissions or surgery performed for these problems.

RESULTS

Demographics

Responses to questionnaires were received from all 8 patients with MEN 2A-HD (100%) and 28 patients with MEN 2B (52%), for a total response rate of 59%. Of the 36 patients responding, 20 were female (MEN 2A-HD, n = 3; MEN 2B, n = 17) and 16 were male (MEN 2A-HD, n = 5; MEN 2B, n = 11). The average age of diagnosis for MEN 2 was 12.8 ± 11.6 years (17.3 ± 19.7 years for MEN 2A-HD and 11.5 ± 7.4 years for MEN 2B;Table 1).

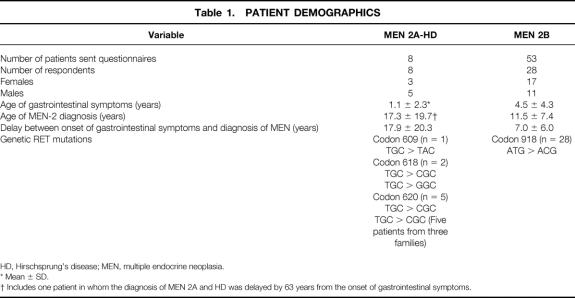

Table 1. PATIENT DEMOGRAPHICS

HD, Hirschsprung’s disease; MEN, multiple endocrine neoplasia.

* Mean ± SD.

† Includes one patient in whom the diagnosis of MEN 2A and HD was delayed by 63 years from the onset of gastrointestinal symptoms.

All patients with MEN 2B had codon 918 mutations of RET on exon 16, whereas patients with MEN 2A-HD had mutations at codons 609 (c609 TGC > TAC, n = 1), 618 (c618 TGC > CGC, n = 1; c618 TGC > GGC, n = 1), and 620 (c620 TGC > CGC, n = 5). A history of gastrointestinal symptoms was described in all patients. For patients with MEN 2A-HD, the onset of gastrointestinal symptoms occurred 1 to 63 years before the diagnosis of MEN (average 17.9 ± 20.3 years). One patient with MEN 2A-HD had undergone a partial colectomy for gastrointestinal obstruction as an infant but was not diagnosed with HD by rectal biopsy until age 63, when she was also diagnosed with MEN 2A.

For patients with MEN 2B, gastrointestinal symptoms presented 1 to 24 years before genetic testing for MEN was performed (average 7.0 ± 6.0 years). All patients were followed up by members of the Department of Surgery at Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO.

Clinical Findings and Radiographic Data

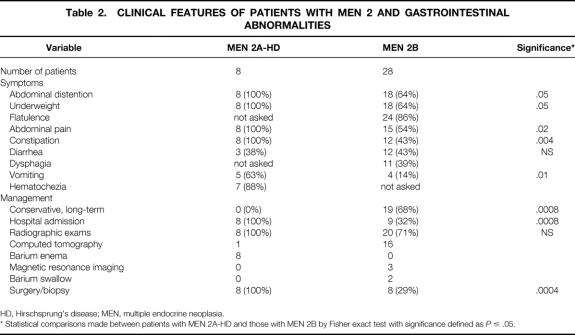

For patients with MEN 2A-HD, 100% of respondents (n = 8) described symptoms of abdominal pain, distention, constipation, and being underweight as children. Seven of eight patients (88%) had hematochezia before surgery for their HD; 63% (5/8) had evidence of vomiting and 38% (3/8) had intermittent diarrhea (Table 2). All of these patients had barium enema examinations before surgery. Typical findings seen on abdominal radiographs and contrast enemas in two patients with MEN 2A-HD are shown in Figure 1.

Table 2. CLINICAL FEATURES OF PATIENTS WITH MEN 2 AND GASTROINTESTINAL ABNORMALITIES

HD, Hirschsprung’s disease; MEN, multiple endocrine neoplasia.

* Statistical comparisons made between patients with MEN 2A-HD and those with MEN 2B by Fisher exact test with significance defined as P ≤ .05.

Figure 1. Radiographs of patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A and Hirschsprung’s disease who had abdominal pain, distention, and vomiting. (A) Abdominal radiograph of 1-month-old patient showing dilated loops of bowel with multiple air–fluid levels and absence of air in the rectum. (B) The same patient’s barium enema showing a dilated sigmoid colon resulting from aganglionosis. Arrows designate an area of narrowing at the rectum. (C) Anterior-posterior view of the same patient. (D) Lateral view of contrast enema in a 7-year-old boy with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A and Hirschsprung’s disease showing a dilated descending colon proximal to a contracted distal segment (black arrows).

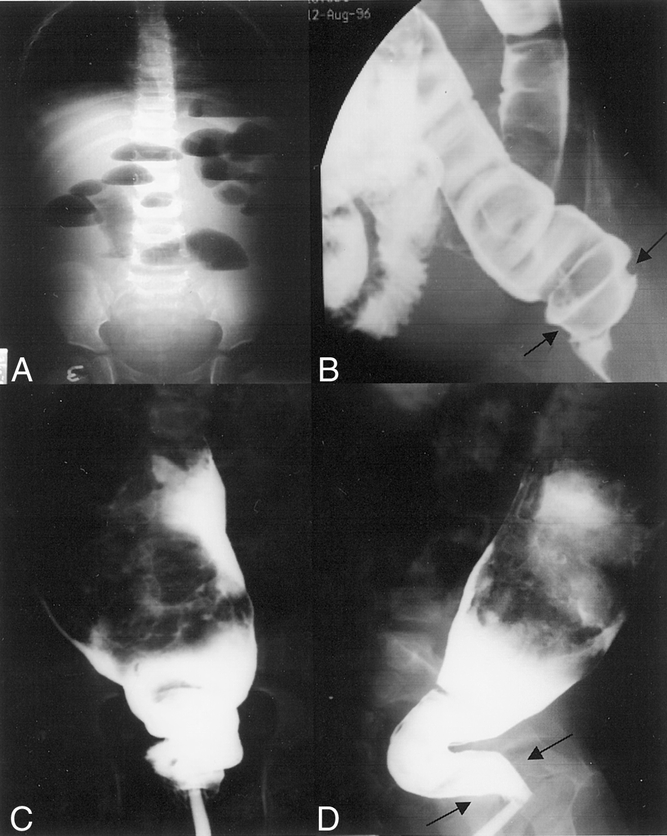

Twenty-six of the 28 (93%) patients with MEN 2B responding to the questionnaires had gastrointestinal symptoms. Eighty-six percent (24/28) described excessive gas or flatulence, 64% (18/28) had abdominal distention, 64% (18/28) noted being underweight during childhood, 54% (15/28) had recurring abdominal pain, 43% (12/28) had frequent diarrhea or constipation, 39% (11/28) noted dysphagia with eating, and 14% (4/28) described intermittent emesis (see Table 2). Twenty patients (71%) had radiographic imaging of their gastrointestinal tract as part of a workup for these symptoms with contrast computed tomography (n = 16), abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (n = 3), and/or barium swallow with small bowel follow-through (n = 2). All patients with MEN 2 who had surgery for gastrointestinal symptoms (MEN 2A-HD = 8, MEN 2B = 8) had preoperative radiographic imaging performed. Typical computed tomography images of megacolon in a patient with MEN 2A-HD and a patient with MEN 2B are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Computed tomography images of megacolon in a patient with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A and Hirschsprung’s disease (top) and a patient with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2B (bottom). The colon is markedly dilated with air in both patients.

Patients with MEN 2A-HD had a significantly higher incidence of abdominal pain, distention, constipation, vomiting, and being underweight as infants compared with patients with MEN 2B (see Table 2).

Patient Management

All of the patients with MEN 2A-HD and 93% of the patients with MEN 2B with gastrointestinal symptoms had medical management initially. Whereas most patients with MEN 2A-HD required surgical resection as infants (7/8), most of the patients with MEN 2B (19/28) were managed conservatively through childhood. These conservative measures included dietary adjustments alone in 15 of 28 patients with MEN 2B (54%), laxatives or enemas in 4 patients (14%), fiber supplements in 4 patients (14%), cisapride in 3 patients (11%), and milk of magnesia in 2 patients (7%). Whereas 68% of patients with MEN 2B (19/28) were managed by conservative measures, 9 patients (32%) had severe symptoms requiring hospital admission.

All eight patients with MEN 2A-HD were admitted to the hospital for their obstructive symptoms, and suction rectal biopsy showed an absence of ganglion cells. Six patients (75%) had diverting sigmoid colostomy followed by colostomy takedown and pull-through procedure (Duhamel, n = 4; Swenson, n = 1; Soave, n = 1). This was performed 3 months to 1 year after the initial colostomy. One patient had total colon aganglionosis and underwent a diverting ileostomy, which was followed at 1 year by an ileostomy takedown and ileal pull-through procedure. The remaining patient had a partial colectomy and diverting colostomy as an infant due to a bowel obstruction. This was followed by a colostomy takedown after 1 year. In this patient, however, a diagnosis of HD was not made until a rectal biopsy and end transverse colostomy was performed for chronic megacolon and obstruction 63 years later.

Nine of 28 patients with MEN 2B (32%) were admitted to the hospital as a result of gastrointestinal symptoms, 8 of whom (29%) had a biopsy or surgical intervention for these symptoms. Four of these nine patients showed evidence of obstruction by clinical and radiographic examination. Three of nine patients had surgical biopsy and removal of large tongue neuromas as their only procedure. One patient had severe dysphagia, vomiting, and gastroparesis requiring gastrostomy tube placement. The remaining patient was admitted for abdominal pain and dysphagia and was discharged home without any procedure performed.

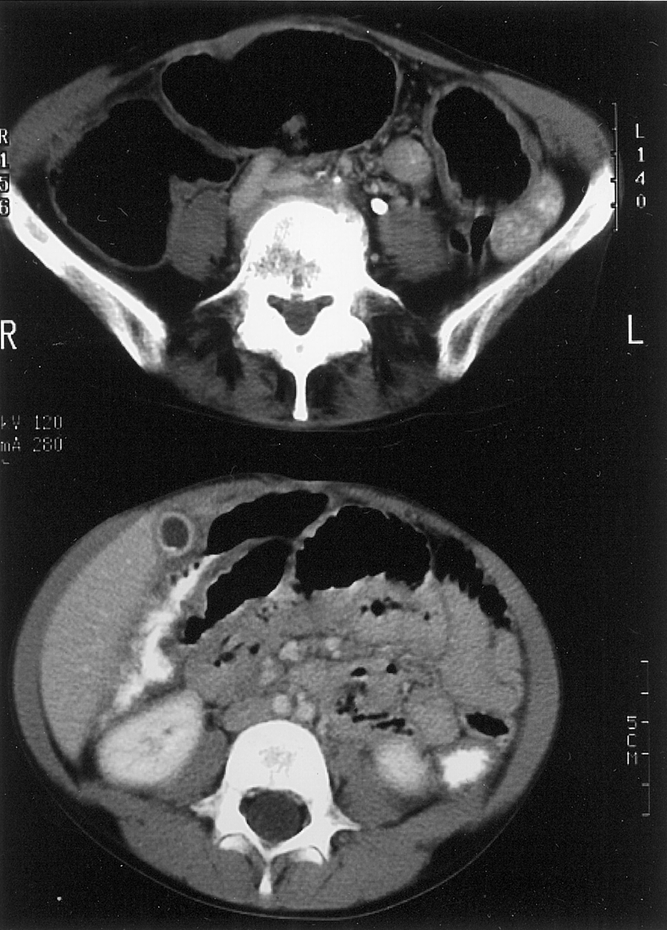

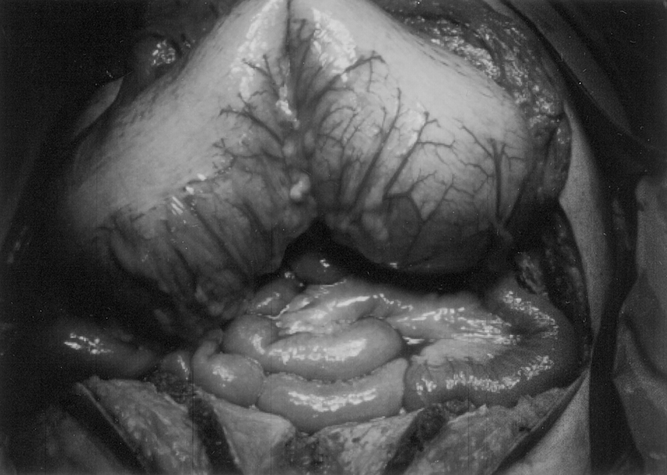

Of the four patients with MEN 2B who underwent surgery for obstruction or perforation, one patient had a left hemicolectomy for megacolon as a child. This patient had two subsequent gastrointestinal operations a laparotomy with a small bowel resection and primary anastomosis for an obstruction secondary to a large intestinal neuroma trapped by adhesions at age 22 and a transverse colectomy and permanent colostomy for a perforated transverse megacolon at age 28. Another patient had a pyloromyotomy as an infant for pyloric stenosis, followed years later by a laparotomy and colectomy for ganglioneuromatosis with megacolon (Fig. 3. The remaining two patients had exploratory laparotomies with small bowel resections and appendectomies for small bowel obstructions secondary to large ganglioneuromas.

Figure 3. Gross intraoperative photograph of a megacolon in a patient with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2B. This patient presented with severe abdominal pain, distention, and vomiting that did not improve with conservative management (Photo courtesy of R. Thompson, MD).

Three of eight patients with MEN 2A (38%) reported complete resolution of their symptoms after surgery. Five patients (62%) reported continuation of intermittent abdominal pain after surgery; four patients (50%) reported recurrent diarrhea; three patients (38%) described periodic incontinence. All patients with MEN 2B stated that their gastrointestinal symptoms were improved after surgery or medical treatment.

DISCUSSION

Gastrointestinal ganglioneuromatosis is the predominant etiology of most alimentary tract symptoms in patients with MEN 2B, resulting in thickening of the myenteric plexi and hypertrophy of ganglion cells. 12–15 These ganglioneuromas may occur anywhere along the gastrointestinal tract and lead to loss of normal bowel tone, distention, segmental dilatation, and megacolon. The number of ganglion cells, however, is not decreased or absent, as with HD. 13

Although the types of symptoms in patients with MEN 2B may vary with the area of the alimentary tract affected, the most frequently reported symptoms in previous studies were constipation and intermittent diarrhea. 15 Constipation may be attributed to hypomotility as a result of ganglionic dysfunction, and abnormal sphincter function at various levels. This symptom usually manifests in infancy and childhood and presents before symptoms of extraintestinal endocrine abnormalities. Diarrhea and constipation were noted in the patients with MEN 2B evaluated in this study, but only 43% described these as frequent symptoms. Most patients documented symptoms of excessive gas, abdominal distention and pain as the most frequent gastrointestinal symptoms they encountered as children and adults.

Patients with MEN 2A and HD present with severe gastrointestinal problems in early childhood or infancy. Abdominal pain, distention, and obstipation dominate the clinical presentation. In children or infants with a suspected diagnosis of HD, the standard diagnostic tools are contrast enema and suction rectal biopsy showing an absence of ganglion cells. The aganglionic segment is removed and a temporary colostomy is constructed. This is usually followed in 3 months to 1 year by a colostomy takedown and pull-through procedure as described by Swenson, Duhamel, or Soave. An alternative to this staged procedure is removal of the aganglionic segment followed by a single-stage pull-through procedure without a colostomy.

All eight patients in this study group have a history typical of HD disease in early life. They underwent surgery with ostomy placement followed by ostomy takedown and pull-through procedures. The symptoms of HD in these patients occurred on average several years before the onset of endocrine neoplasia.

In this study group, all patients with MEN 2A had mutations in codons 609, 618, or 620 of the RET protooncogene. 4 These mutations, described in other patients with MEN 2A-HD, result in a “gain of function” in the RET protein product and are associated with the development of other features of MEN 2. A number of kindreds with familial HD who do not have MEN 2 have germline mutations of RET that are inactivating or “loss-of-function” mutations. 4,7 It is not known why patients with certain gain-of-function RET mutations develop HD in addition to MTC, whereas other patients with familial HD have loss-of-function mutations.

One patient in this study group, in whom the diagnosis of HD was not entertained at the time of her initial bowel surgery as a child, experienced chronic constipation and abdominal pain throughout her life until a rectal biopsy was performed at age 63, when she presented with recurrent megacolon. An end colostomy was performed at this time, as the patient did not wish to have any further surgery. This patient’s late age of diagnosis adds a large standard deviation (± 20.3 years) to the average number of years gastrointestinal symptoms appeared before a diagnosis of MEN 2A was made. If this patient is removed from the calculation for the group of patients with MEN 2A, then the average delay between the onset of gastrointestinal symptoms and the diagnosis of MEN 2A is reduced to 1.2 ± 2.4 years.

Surgical management of HD in the patients with MEN 2A in this series corrected the development of megacolon or obstruction but did not resolve significant gastrointestinal symptoms in 62% of patients, who reported continued intermittent abdominal pain after surgery. Fifty percent reported recurrent diarrhea and 38% described a new onset of periodic incontinence after surgery. This complication rate, although higher than that expected by the procedure alone (12–37%), is not uncommon. 16 Although no prospective trials have compared the various operations for HD, a significant complication rate still exists, including the development of colitis, obstruction, infection, leak, stricture, and fistula. Postoperative gastrointestinal symptoms usually involve constipation and incontinence, which has been reported at a relatively high incidence (10–27%) in some studies. 16,17

Patients with MEN 2B develop chronic megacolon, but HD has not been reported in this group of patients. In this study group, 68% of the patients with MEN 2B (19/28) were able to manage their gastrointestinal symptoms conservatively with medication and dietary changes. The remaining nine patients (32%) had symptoms severe enough to require hospital admission, with eight patients (29%) having severe symptoms necessitating surgical biopsy or celiotomy for obstruction. In these patients, surgical management improved symptoms in five of eight patients (63%). The remaining three of eight patients (37%) continued to manage their gastrointestinal symptoms with conservative measures. Radiographic examination of the alimentary tract is helpful in localizing abnormalities and mucosal neuromas as well as characterizing the extent of megacolon. In this study, 71% of patients with MEN 2B had radiographic evaluations (100% for patients requiring surgery for their disease) for gastrointestinal symptoms. In addition to megacolon, these patients may also demonstrate abnormal haustral markings, thickened mucosal folds, and diverticula on radiographic imaging. 13

Patients with MEN 2A-HD also had a significantly higher incidence of abdominal pain, distention, constipation, vomiting, and being underweight as infants compared with patients with MEN 2B (see Table 2). Patients with MEN 2B, however, had a significantly decreased incidence of symptoms requiring hospital admission or surgical management and a significantly higher likelihood of being able to manage their symptoms conservatively. This may be attributed to the higher level of morbidity associated with the absence of ganglion cells in HD compared with the intestinal ganglion hypertrophy seen in MEN 2B. However, the significance of these findings carries a degree of objective bias: the results are derived from patients’ perspectives of their pain and symptoms, which were not normalized or compared with control patients with similar symptoms or operations. Despite this bias, it may be said that in general, the gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with MEN 2A-HD were more severe than those in patients with MEN 2B and always resulted in surgical management.

In patients with MEN 2B who develop gastrointestinal symptoms, conservative measures should be attempted initially because less than a third of patients will develop symptoms requiring surgery, and most gastrointestinal symptoms can be managed with conservative techniques on a long-term basis. In patients with MEN 2A, in contrast, the development of gastrointestinal symptoms, especially in infancy, warrants an investigation to rule out the diagnosis of HD, because its presence will almost certainly result in surgical interventions and a higher severity of symptoms. Of note, this study reviewed only patients with MEN 2A with documented HD. Although other patients with MEN 2A may have occasional gastrointestinal symptoms, these typically do not require lifestyle alterations and are no different than what is encountered in the general population.

Early diagnosis of MEN 2 is important in avoiding unnecessary abdominal surgery and identifying patients at risk for subsequent endocrine malignancies. Because gastrointestinal symptoms usually present in these patients many years before the development of endocrine neoplasia, the diagnosis of MEN 2 is frequently not considered or is delayed. Alternatively, some cases of MEN 2B and MEN 2A-HD become evident at a young age only because of these gastrointestinal manifestations. Because MTC in patients with MEN 2B may develop in infancy, 18 it is important for clinicians managing these patients to understand the presentation of symptoms and the progression of gastrointestinal abnormalities in its two subtypes. For patients from well-documented MEN 2A kindreds, genetic testing may identify those at highest risk for the development of gastrointestinal problems and HD. We recommend that all patients with biopsy-proven HD, as well as infants or children with megacolon, should have genetic testing for the presence of mutations in the RET protooncogene; this may lead to an earlier diagnosis of MEN 2A and MEN 2B, respectively. Identifying these patients at a younger age allows for earlier detection and treatment of MTC and other endocrine abnormalities.

Discussion

Dr. Richard E. Goldstein (Nashville, TN): I appreciate the opportunity to comment on this paper. While most surgeons tend to focus largely on medullary thyroid cancer and pheochromocytomas that are associated with MEN 2A and MEN 2B, this study demonstrates that we also really need to consider the GI manifestations that may significantly affect this population. In order to ferret these manifestations out, it is necessary that a large number of families with MEN 2A and 2B be available for study, and that is precisely why Dr. Moley and colleagues are one of the few groups who can really address this question. Starting with the efforts of Dr. Wells, they have really built up and vigorously studied a large number of kindreds with MEN 2A and MEN 2B. I do have several questions. While a high percentage of the patients with MEN 2B have GI manifestations, we are comparing this to only those MEN 2A patients with Hirschsprung’s. I would assume, although I don’t think it was mentioned in the manuscript, that this was a very small percentage of MEN 2A patients. I would ask Dr. Moley and his colleagues to comment on the prevalence of Hirschsprung’s in this overall MEN 2A group. Second, obviously some of these patients have pheochromocytomas. Does the timing or the presence of the pheo, could that have been a factor as far as the patients stating that they had GI complaints? In other words, could excess epinephrine or norepinephrine have been around that may have altered their answers, and was that factored in? Lastly, as many studies have, there can be some slight selection bias, and while all eight of the MEN 2A Hirschsprung’s disease answered their questionnaire, only 52% of the MEN 2B patients sent theirs back in. Potentially, those patients who have symptoms will want somebody to know that and so they will send it back in, whereas those patients who don’t have symptoms don’t send it back in. Can that be a factor, and has that been taken into account?

I want to thank you for asking me to look this over, and I thank the Southern Surgical for the privilege of the floor.

Dr. Robert Udelsman (New Haven, CT): Dr. Moley and his colleagues have addressed the lesser-known GI manifestations of the MEN syndromes. I agree with Dr. Goldstein that this study emphasizes the power obtained by following a large group of families in a single institution. I have three questions. I was surprised to learn that 93% of the patients with MEN 2B had GI symptoms 1 to 24 years before the diagnosis of MEN 2B. Since these patients have a typical phenotypic expression of their disease, I am curious as to why this long lag period existed in this population. Two, MEN patients from known kindreds are now being diagnosed in childhood due to the availability of RET protooncogene screening. How has the diagnosis of this syndrome modified your evaluation of GI symptoms in patients who are asymptomatic; that is, are you doing anything special once you diagnose either MEN 2A or 2B? Finally, and perhaps the most important aspect that I am curious about, you recommend that all patients with biopsy-proven Hirschsprung’s disease as well as children who manifest megacolon should undergo genetic screening for RET protooncogene mutations. Although this seems to be a prudent recommendation, could you postulate about both the theoretic yield as well as the cost of such screening?

I would like to congratulate the authors on a nicely written and presented manuscript and thank the Society for the privilege of the floor.

Dr. James A. O’Neill, JR. (Nashville, TN): I have a simple question for Dr. Moley. The material may be resident in his excellent material. And that is, in the group that had megacolon and was not clear-cut familial Hirschsprung’s disease, did any of those patients have suction biopsies? And particularly if they did and had acetylcholinesterase staining done, did any of them have intestinal neuronal dysplasia, which is a sort of pseudo-Hirschsprung’s accompaniment in that category of patients?

Dr. Mark S. Cohen (St. Louis, MO): Drs. Carey and Townsend, members and guests of the Association, I thank you for the privilege of the floor. I would also like to thank Dr. Goldstein and Dr. Udelsman for reviewing our manuscript and for their questions.

Dr. Goldstein, with regard to the prevalence of Hirschsprung’s disease in the MEN 2A population, of the 83 kindreds we follow at our institution, which accounts for about 1,200 patients, only 8 patients were found to have biopsy-confirmed Hirschsprung’s disease. This comes to an incidence of about 0.7%. In terms of catecholamine imbalances from endocrine tumors causing the gastrointestinal symptoms in these patients, I don’t believe this is the case, since these patients mostly expressed complaints and symptoms in infancy and early childhood, well before the development of thyroid tumors or pheochromocytomas which could produce such catecholamine-related symptoms. These patients were too young for endocrine tumors to be responsible for their symptoms. Regarding your question on whether the patients who did not return their questionnaires were the patients without symptoms, I do not think that is the case. Although we had a 52% response rate for MEN 2B patients, a few of those that responded stated they had minimal or no gastrointestinal symptoms. While only the questionnaire data were used to objectively tabulate gastrointestinal symptoms in these patients, most of the patients who did not respond to the questionnaire also complained of gastrointestinal symptoms in childhood. This is based on discussions with these patients in the office not included in the data set. In terms of the population of patients in this study, however, I believe the questionnaire responses accurately reflect the gastrointestinal symptoms experienced by MEN 2 patients.

Dr. Udelsman asked about the time delay of up to 24 years between the phenotypic expression of symptoms and the diagnosis of MEN. In our MEN 2B group, 93% of patients expressed gastrointestinal symptoms years before they developed medullary thyroid carcinoma or C-cell hyperplasia. Part of this explanation is that GI symptomatology is not usually associated with MEN 2 syndromes by most physicians. The other part of the explanation is that often the GI symptoms experienced by these patients were treatable by conservative measures and did not require surgical intervention. It was only when endocrine or mucosal tumors of their syndrome developed that the diagnosis of MEN was made.

In terms of how our institution is handling genetic testing of Hirschsprung patients for MEN, we advocate testing in all children who present with megacolon or Hirschsprung’s disease. If a diagnosis of MEN is made, these children will have prophylactic thyroidectomies. Early genetic testing allows children with MEN 2 to have thyroidectomies before the development of medullary thyroid cancer, which will occur in all of these patients eventually if untreated.

Regarding the cost-effectiveness of genetic testing for MEN in patients with Hirschsprung’s disease, the incidence of Hirschsprung’s disease in the population is approximately 1 in 5,000. Some studies have reported between a third and a half of Hirschsprung’s patients have mutations in the RET protooncogene, with fewer of these being codon 609, 618, or 620 mutations. Because of the small number of patients that would be tested and the potential life-saving benefit of offering MEN 2 patients a thyroidectomy at an early age to decrease or eliminate the risk of developing medullary thyroid cancer later in life, we feel this is a cost-effective measure at this time.

Finally, Dr. O’Neill asked whether any of the MEN 2B patients had biopsies of their megacolon and whether there was evidence of intestinal neuronal dysplasia. In this group, two patients had biopsies and one demonstrated intestinal neuronal dysplasia, so this is seen.

Footnotes

Presented at the 113th Annual Session of the Southern Surgical Association, December 3–5, 2001, Hot Springs, Virginia.

Correspondence: Jeffrey F. Moley, MD, Washington University School of Medicine, Box 8109, 660 S. Euclid Ave., St. Louis, MO 63110.

E-mail: moleyj@msnotes.wustl.edu

Accepted for publication December 2001.

References

- 1.Romeo G, Ronchetto P, Luo Y, et al. Point mutations affecting the tyrosine kinase domain of the RET proto-oncogene in Hirschsprung’s disease. Nature 1994; 367: 377–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edery P, Lyonnet S, Mulligan LM, et al. Mutations of the RET proto-oncogene in Hirschsprung’s disease. Nature 1994; 367: 378–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Decker RA, Peacock ML, Watson P. Hirschsprung disease in MEN 2A: increased spectrum of RET exon 10 genotypes and strong genotype–phenotype correlation. Hum Mol Genet 1998; 7: 129–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kikumori T, Evans D, Lee JE, et al. Genetic abnormalities in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2. In: Doherty GM, Skogseid B, eds. Surgical endocrinology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001: 531–540.

- 5.Caron P, Attié; T, David D, et al. C618R mutation of exon 10 of the RET proto-oncogene in a kindred with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A and Hirschsprung’s disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1996; 81: 2731–2733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mulligan LM, Eng C, Attié; T, et al. Diverse phenotypes associated with exon 10 mutations of the RET proto-oncogene. Hum Mol Genet 1994; 3: 2163–2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borst MJ, VanCamp JM, Peacock ML, Decker RA. Mutational analysis of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A associated with Hirschsprung’s disease. Surgery 1995; 117: 386–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eng C, Clayton D, Schuffenecker I, et al. The relationship between specific RET proto-oncogene mutations and disease phenotype in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2: International RET Mutation Consortium analysis. JAMA 1996; 276: 1575–1579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Romeo G, Ceccherini I, Celli J, et al. Association of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 and Hirschsprung disease. J Intern Med 1998; 243: 515–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verdy M, Weber AM, Roy CC, et al. Hirschsprung’s disease in a family with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1982; 1: 603–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Decker RA, Peacock ML. Occurrence of MEN 2a in familial Hirschsprung’s disease: a new indication for genetic testing of the RET proto-oncogene. J Pediatr Surg 1998; 33: 207–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahaffey SM, Martin LW, McAdams J, et al. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type II B with symptoms suggesting Hirschsprung’s disease: a case report. J Pediatr Surg 1990; 25: 101–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khan AH, Desjardins JG, Youssef S, et al. Gastrointestinal manifestations of Sipple syndrome in children. J Pediatr Surg 1987; 22: 719–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carney JA, Go VL, Sizemore GW, et al. Alimentary-tract ganglioneuromatosis: a major component of the syndrome of multiple endocrine neoplasia, type 2b. N Engl J Med 1976; 295: 1287–1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Demos TC, Blonder J, Schey WL, et al. Multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) syndrome type IIB: gastrointestinal manifestations. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1983; 140: 73–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skinner MA. Hirschsprung’s disease. Curr Probl Surg 1996; 33: 389–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heij HA, de Vries X, Bremer I, et al. Long-term anorectal function after Duhamel operation for Hirschsprung’s disease. J Pediatr Surg 1995; 30: 430–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stjernholm MR, Freudenbourg JC, Mooney HS, et al. Medullary carcinoma of the thyroid before age 2 years. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1980; 52: 252–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]