Abstract

Objective

To examine the long-term outcomes of patients with melanoma metastatic to regional lymph nodes.

Summary Background Data

Regional lymph node metastasis is a major determinant of outcome for patients with melanoma, and the presence of regional lymph node metastasis has been commonly used as an indication for systemic, often intensive, adjuvant therapy. However, the risk of recurrence varies greatly within this heterogeneous group of patients.

Methods

Database review identified 2,505 patients, referred to the Duke University Melanoma Clinic between 1970 and 1998, with histologic confirmation of regional lymph node metastasis before clinical evidence of distant metastasis and with documentation of full lymph node dissection. Recurrence and survival after lymph node dissection were analyzed.

Results

Estimated overall survival rates at 5, 10, 15, and 20 years were 43%, 35%, 28%, and 23%, respectively. This population included 792 actual 5-year survivors, 350 10-year survivors, and 137 15-year survivors. The number of positive lymph nodes was the most powerful predictor of both overall survival and recurrence-free survival; 5-year overall survival rates ranged from 53% for one positive node to 25% for greater than four nodes. Primary tumor ulceration and thickness were also powerful predictors of both overall and recurrence-free survival in multivariate analyses. The most common site of first recurrence after lymph node dissection was distant (44% of all patients).

Conclusions

Patients with regional lymph node metastasis can enjoy significant long-term survival after lymph node dissection. Therefore, aggressive surgical therapy of regional lymph node metastases is warranted, and each individual’s risk of recurrence should be weighed against the potential risks of adjuvant therapy.

Regional lymph node metastasis is regarded as a major determinant of outcome for many malignancies, including melanoma. Particularly for melanoma, however, the risk of recurrence and death for patients with regional metastasis varies widely. Overall 10-year survival rates range from 25% to 40%, and survival rates for various subgroups of patients range from 10% to 70%. 1–7 Numerous clinical and pathologic variables have been examined with the goal of identifying factors that distinguish high-risk from low-risk patients. Many of these studies were published in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when the roles of adjuvant therapy and elective lymph node dissections were two of the most controversial issues in surgical oncology. A decade and several important clinical trials later, interferon-α (IFN-α) has been approved by the U.S. Food & Drug Administration, sentinel lymph node biopsy has largely replaced elective lymph node dissection as a lymph node staging procedure, and the role of adjuvant therapy remains a controversial issue. Therefore, it is more important than ever to be able to accurately assess the risk of recurrence for patients with regional lymph node metastasis. Recently, the Melanoma Staging Committee of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) published the largest prognostic factor analysis to date, including 1,500 patients with regional lymph node metastasis at the time of initial staging. 8 Our study—an analysis of recurrence and survival in 2,505 patients with regional lymph node metastasis either synchronous or metachronous to their primary disease—further describes the long-term outcomes of patients with node-positive melanoma.

METHODS

Between 1970 and 1998, more than 10,000 patients were referred to the Duke University Melanoma Clinic with cutaneous melanoma. Retrospective review of a prospectively maintained database identified 2,505 patients who met the following criteria: only one melanoma primary (known or unknown site); histologic confirmation of regional lymph node metastasis before clinical evidence of distant metastasis; and documentation of full lymph node dissection within 6 weeks of confirmed lymph node metastasis. Patients with confirmed lymph node metastasis but without documented full lymph node dissection (n = 706) within the specified time period were excluded. Inguinal and iliac nodes were considered to be regional metastases for lower extremity and lower trunk primaries; axillary nodes, for upper extremity, upper trunk, head, and neck primaries; and cervical (including supraclavicular and parotid) nodes, for upper trunk, head, and neck primaries. Other patterns of lymph node metastasis were considered to be distant and were excluded. Patients with local or in-transit recurrence (6.1%) before or concurrent with regional lymph node metastasis were not excluded.

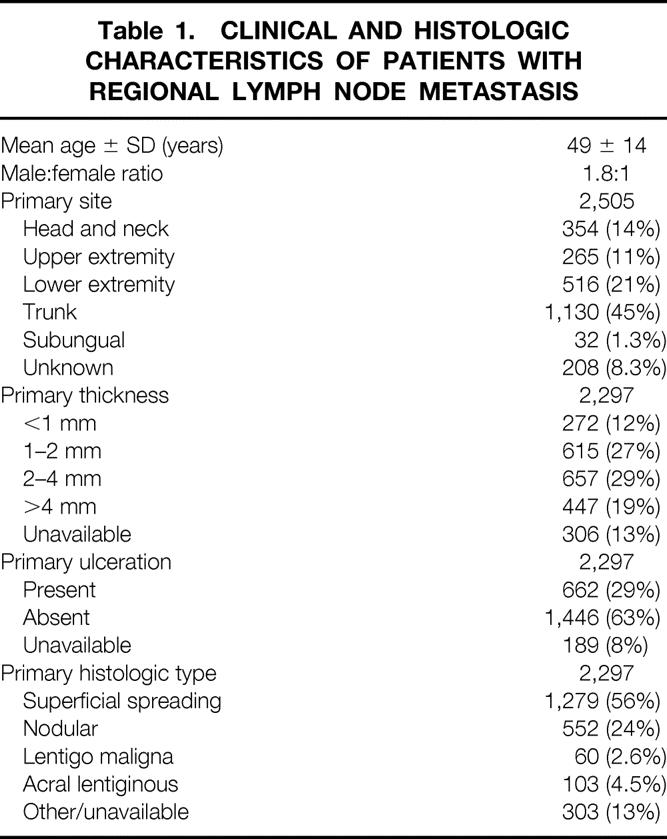

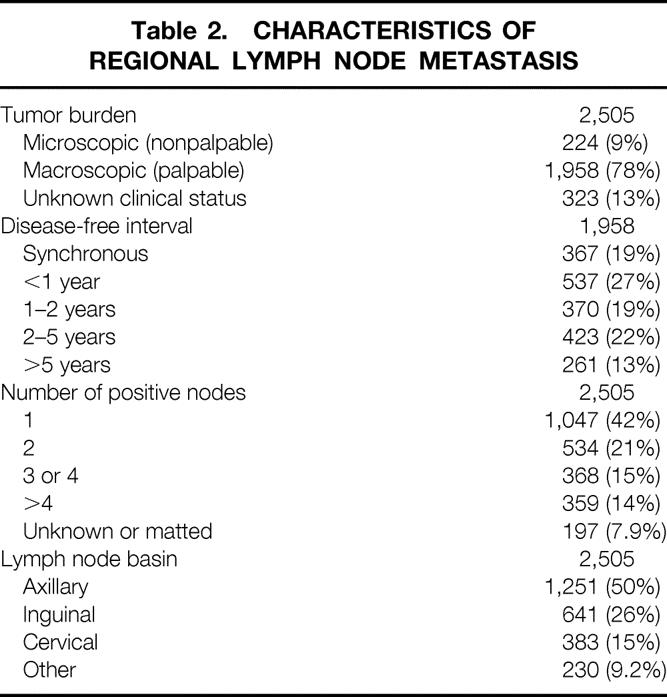

The clinical characteristics of these 2,505 patients and the histologic characteristics of the 2,297 known primary tumors are listed in Table 1. The characteristics of their regional lymph node metastases are listed in Table 2. Microscopic tumor burden was defined as the detection of metastasis by routine histology or immunohistochemistry in clinically nonpalpable lymph nodes. Disease-free interval (from the diagnosis of primary to the diagnosis of regional lymph node disease) was calculated only for patients with macroscopic tumor burden (palpable lymph nodes).

Table 1. CLINICAL AND HISTOLOGIC CHARACTERISTICS OF PATIENTS WITH REGIONAL LYMPH NODE METASTASIS

Table 2. CHARACTERISTICS OF REGIONAL LYMPH NODE METASTASIS

Standard practice at our institution during most of this time period was observation of nonpalpable lymph nodes and therapeutic lymph node dissection for palpable lymph nodes. However, microscopic lymph node metastases were detected by elective lymph node dissections (at Duke or referring institutions) in 191 patients (8% of study population) and, since 1995, by sentinel lymph node biopsy followed by completion lymph node dissection in 33 patients (1.3%). Experimental adjuvant specific active immunotherapy was received by 95% of patients at some time during their course of treatment. This therapy was offered to high-risk (≥ 1mm thick primary or stage 2) patients rendered disease-free by surgery and consisted predominantly of vaccination with irradiated, cultured allogeneic or autologous melanoma cells. The details of the various vaccine strategies used have been described elsewhere. 1,9–11

Overall survival and recurrence-free survival were measured from the date of histologic confirmation of regional lymph node metastasis to the date of death due to any cause or date of first recurrence after lymph node dissection, respectively. Survival probabilities were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method, and the Cox-Mantel rank test was used to compare survival between subgroups. For multivariate analyses of survival, Cox simultaneous proportional hazards models were constructed, incorporating factors that were statistically significant (P < .05) on univariate analysis. Recurrence patterns were compared between subgroups by chi-square analysis.

RESULTS

Survival

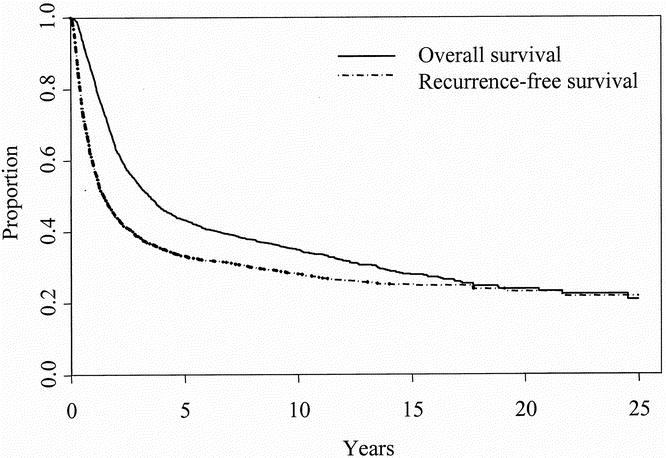

For 2,505 patients undergoing full lymph node dissection for regional lymph node metastases, the median overall survival was 3.4 years, compared with a median recurrence-free survival of 1.5 years. Estimated overall survival rates (95% confidence limits) at 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 years were 43% (41–45%), 35% (33–37%), 28% (25–30%), 23% (20–26%), and 19% (13–24%), respectively (Fig. 1). Estimated recurrence-free survival rates at 5, 10, 15, and 20 years were 33% (31–35%), 28% (26–30%), 25% (23–27%), and 22% (18–26%) respectively, with patients dying of causes unrelated to melanoma not counted as recurrences. Both curves appeared to plateau at approximately 20%, with no first recurrences after 21 years. Further, although greater than 90% of deaths before 10 years were attributable to melanoma or its treatment, most deaths after 15 years were unrelated to melanoma.

Figure 1. Overall and recurrence-free survival of patients with regional lymph node metastasis treated with full lymph node dissection (n = 2,505).

The median length of follow-up in surviving patients was 6.3 years, and only 5% of surviving patients had follow-up of less than 2 years. This population included 792 actual 5-year survivors, 350 actual 10-year survivors, 137 actual 15-year survivors, and 46 actual 20-year survivors. For 5-year survivors, the probability of surviving an additional 10 years was 64% (60–69%). For 10-year survivors, the probability of surviving an additional 10 years was 68% (61–76%).

Univariate Analyses

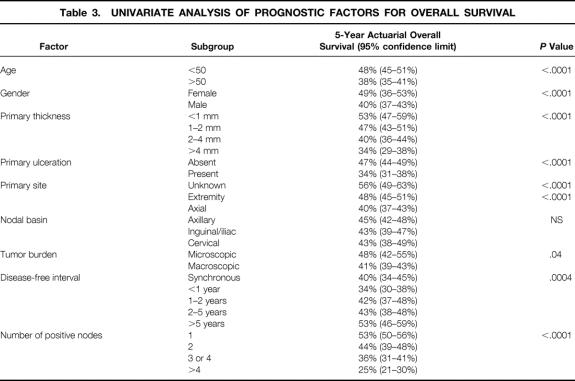

Estimated 5-year overall survival data for several subgroups are summarized in Table 3. Age was highly significant as a continuous variable, with 50 years of age representing an obvious breakpoint after which risk increased rapidly. Gender, primary tumor thickness (as a continuous variable or by T stage), and primary tumor ulceration all remained significant predictors of overall survival after the development of regional lymph node metastasis. Unknown primary tumor site was associated with a significantly better prognosis than known primary site, in general, and extremity tumors were associated with a better prognosis than axial (trunk, head, and neck) tumors.

Table 3. UNIVARIATE ANALYSIS OF PROGNOSTIC FACTORS FOR OVERALL SURVIVAL

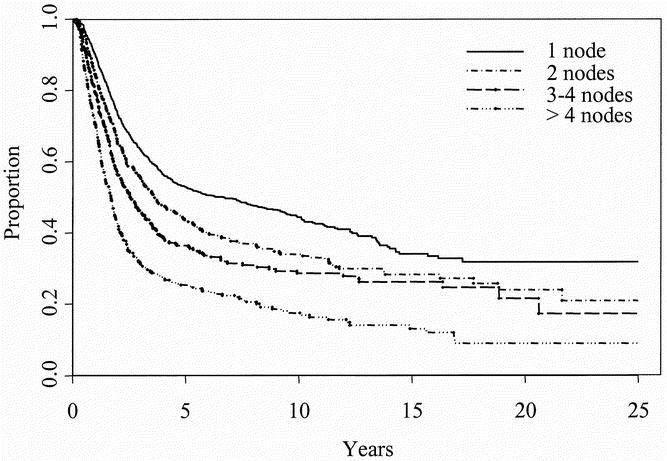

No differences in overall survival were observed based on the location of the regional lymph node metastasis (axillary, inguinal/iliac, or cervical). Improved overall survival was noted in patients with microscopic tumor burden (elective lymph node dissection or sentinel lymph node biopsy with selective lymph node dissection). When only patients with macroscopic tumor burden were considered, disease-free interval before lymph node dissection was positively associated with improved survival after lymph node dissection; the worst survival was noted in patients with metachronous lymph node metastasis presenting within 1 year of their primary disease. Finally, the number of positive lymph nodes was the most powerful factor by which to stratify patients (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Overall survival in subsets of patients with one (n = 1,047), two (n = 534), three or four (n = 368), and greater than four (n = 359) positive lymph nodes.

In general, prognostic factors for recurrence-free survival were similar to those for overall survival. Notable exceptions were the findings that inguinal or iliac lymph node dissection was associated with worse recurrence-free survival than axillary lymph node dissection (P = .039), microscopic tumor burden was a more significant predictor of recurrence-free survival than of overall survival (P = .007), and age was a less significant predictor of recurrence-free survival than of overall survival (P = .025).

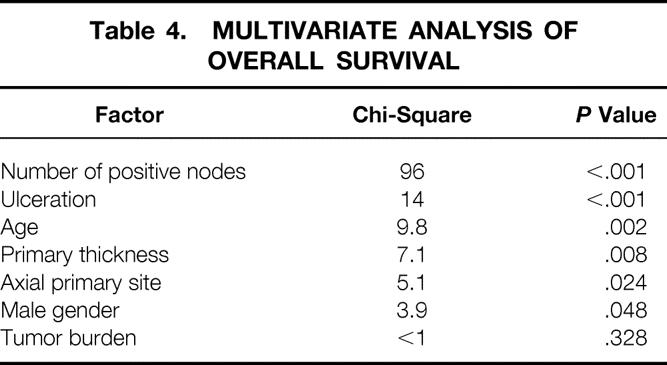

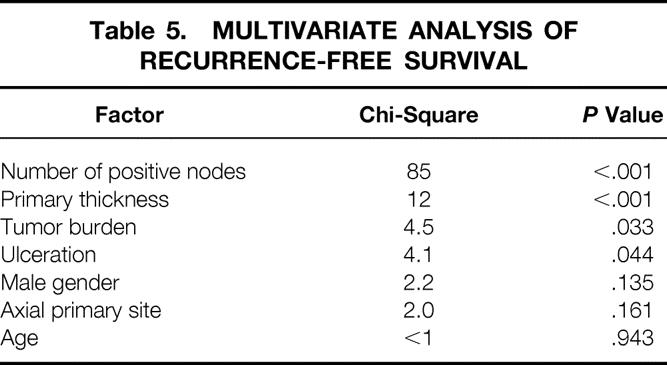

Multivariate Analyses

Significant factors in the univariate analysis of overall survival (age, gender, primary tumor thickness, primary tumor ulceration, primary tumor site, tumor burden, and number of positive nodes) were used in multivariate analyses of overall and recurrence-free survival. Due to the interaction between tumor burden and disease-free interval (all patients with microscopic tumor burden underwent lymph node dissections during their initial staging period), the latter factor was excluded from these analyses. All data were available for 1,730 patients. Patients with unknown primaries were excluded from the multivariate analysis, because ulceration and primary thickness data were not available.

The number of positive lymph nodes was again the most powerful predictor of overall survival (Table 4). Ulceration, age, and primary thickness remained highly significant independent risk factors. Axial primary site (vs. extremity) and male gender also achieved statistical significance. Tumor burden (macroscopic vs. microscopic), however, was not predictive of overall survival when these other factors were incorporated into a multivariate model.

Table 4. MULTIVARIATE ANALYSIS OF OVERALL SURVIVAL

When the same factors were incorporated into a multivariate analysis of recurrence-free survival, the number of positive lymph nodes remained the most powerful predictive factor, and primary thickness and ulceration remained significant independent risk factors (Table 5). In addition, tumor burden, which was not a significant predictor of overall survival, was a significant predictor of recurrence-free survival. Conversely, age, primary site, and gender, which were significant predictors of overall survival, were not significant predictors of recurrence-free survival.

Table 5. MULTIVARIATE ANALYSIS OF RECURRENCE-FREE SURVIVAL

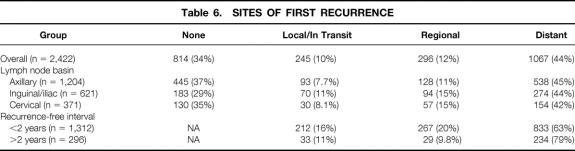

Patterns of Recurrence

Sites of recurrence after lymph node dissection were categorized as local or in transit (occurring near the site of the primary or between the site of the primary and a regional lymph node basin), regional (occurring in the previously dissected nodal basin), and distant. No recurrence was evident at last follow-up or at death in 34% of patients, in whom the site of first recurrence was “none.” The site of first recurrence was unknown in 3% patients, who were excluded from this analysis. The sites of first recurrence for the overall population of patients undergoing lymph node dissection as well as for various subgroups are provided in Table 6. Overall and across all subgroups, the most common site of first recurrence was distant, with distant skin, distant lymph nodes, and lungs being the most common specific sites. In 12% of patients overall, the “distant” site of first recurrence was a regional lymph node basin different than the previously dissected nodal basin, predominantly in patients with trunk primaries. Local or in transit disease and regional lymph nodes were sites of first recurrence in 10% and 12% of patients and sites of recurrence (first or ever) in 12% and 14% of patients, respectively. Local or in transit (P = .01) and regional recurrences (P < .01) were more common after inguinal or iliac lymph node dissection than after axillary lymph node dissection. Local or in transit and regional recurrences also represented a larger proportion of first recurrences within 2 years of lymph node dissection than of first recurrences more than 2 years after lymph node dissection (P < .01). After initial local or regional recurrence, subsequent distant recurrence was recorded in greater than 60% of patients. In contrast, after initial distant recurrence, subsequent local or regional recurrence was recorded in fewer than 5% of patients.

Table 6. SITES OF FIRST RECURRENCE

DISCUSSION

Regional lymph node metastasis is a powerful predictor of recurrence and death in patients with melanoma. Disagreement exists, however, over whether nodal metastasis should be thought of as an orderly progression from local to regional to distant disease or as a marker of systemic disease. Therefore, the respective roles of surgical and systemic therapies in the management of node-positive patients are controversial. Indeed, the therapeutic value of elective lymph node dissections and the role of adjuvant therapy for node-positive disease have been two of the most studied and least agreed on issues in the treatment of melanoma. Since the ECOG 1684 study, published in 1996, showed a survival benefit of adjuvant IFN-α for node-positive melanoma, 12 the presence of regional lymph node metastasis has been commonly used as an indication for systemic, often intensive, adjuvant therapy.

With the advent of sentinel lymph node biopsy, the elective staging of clinically negative lymph nodes has become less morbid and more accurate. 13,14 Meanwhile, experimental adjuvant therapies, including several melanoma vaccines, continue to be developed as less toxic alternatives to IFN-α. Now it is more important than ever to be able to risk-stratify patients with node-positive melanoma to determine which subsets of patients benefit from adjuvant therapy, as well as to compare results between trials of adjuvant therapy. Data have been prospectively collected for 2,505 patients with regional lymph node metastasis treated with full lymph node dissection between 1970 and 1998, allowing sufficient numbers of patients and length of follow-up to examine long-term outcomes in this population.

Survival

The overall survival rates of 43%, 35%, and 28% at 5, 10, and 15 years reported here are similar to those reported for this same database in 1988 1 and are similar or better to the rates reported in other large studies. 2,4,5,8 Endpoints in most studies have been survival rates at 5 and 10 years, intervals during which patients with melanoma continue to recur. Our study found a 20-year overall survival rate of 23%, and survival curves began to plateau after 20 years at approximately 20%. Estimated survival rates can be overly optimistic; however, the significant numbers of actual 15- and 20-year survivors in this population support the possibility of long-term survival and allow for accurate estimation of long-term survival rates, as evidenced by their narrow confidence limits. Further, for 137 actual 15-year survivors, the probability of dying of melanoma was less than 10%, and there were no first recurrences after 21 years. These data suggest that cure is possible in patients with regional lymph node metastases.

As a tertiary medical center engaged in experimental immunotherapy, our institution is frequently referred patients with regional metastasis and high-risk primary disease from outside institutions, and 95% of patients in this study participated in trials of different vaccine strategies. Therefore, it is not possible to attribute the observed outcomes entirely to lymph node dissection. Several types of melanoma vaccine, including whole cell, peptide, and ganglioside vaccines, have shown promise as adjuvant therapy for stage 3 disease in nonrandomized and small, randomized trials, 1,15–20 but none yet has been effective in a large, randomized controlled trial. 21,22 Therefore, although the survival rates in our study may be in small part attributable to adjuvant therapy, they more likely reflect the tumor biology of regionally metastatic melanoma that has been adequately treated with surgery.

The most powerful predictor of survival in this study, as in most other studies of node-positive melanoma, was the number of positive lymph nodes. Stratification by this factor alone reveals a wide range of estimated 5-year survival rates, from 53% for patients with one positive node to 25% for patients with more than four positive nodes. This observation has been so consistent that the number of positive lymph nodes replaced gross dimension in the N classification of the recently revised AJCC staging system, 23 with N1, N2, and N3 designating one, two or three, and four or more nodes, respectively. However, even in the subgroups of patients with multiple positive nodes, significant long-term survival is possible.

Other studies have also shown that characteristics of the primary tumor remain important independent predictors of survival even after the development of regional lymph node metastasis. Ulceration was one of the most powerful predictors of survival for patients with stage 1, 2, and 3 disease in the recent AJCC study, 8 as it was for regional lymph node metastasis in our study. Primary tumor thickness 4,6 and site 4,7,8 have less consistently been shown to be predictors of survival after lymph node metastasis, but previous studies have varied in the inclusion of metachronous lymph node metastasis, the relative proportions of elective and therapeutic dissections, and in size. The more than 1,700 patients included in our multivariate analysis provided sufficient power to detect these associations. In addition, lymph node metastases from unknown primary sites have previously been associated with equivalent 24 or better 25 survival than metastases from known primary sites. The significant survival benefit associated with an unknown primary site in our study supports the hypothesis that regression of the primary tumor correlates with a strong immunologic response to the tumor. Similarly, our study shows the intuitive theory that a long disease-free interval is associated with less aggressive disease and improved survival. The seemingly paradoxical finding that synchronous lymph node metastasis was associated with better survival than metachronous lymph node metastasis with a disease-free interval of less than 1 year is attributable to the fact that regional metastases from unknown primary sites—with their observed survival benefit—were considered to be synchronous lymph node metastases.

Age is another factor that not surprisingly has been associated with decreased overall survival at every stage of disease: age is positively associated with risk for death. However, that age was not predictive of recurrence-free survival is consistent with the idea that older patients are not necessarily more likely to recur, but that they are more likely to die, from melanoma as well as nonmelanoma causes. Female gender has also uniformly been associated with a better prognosis. This survival benefit is largely accounted for by differences between the genders in primary tumor thickness, ulceration, and site: women are more likely to have thin, nonulcerated melanomas located on the extremities. 26 This study suggests that gender is an independent predictor of overall survival, although not of recurrence-free survival. Similar to older patients, men may not be at greater risk for recurrence when these other risk factors are considered, but they may be at greater risk than women for death from melanoma and nonmelanoma causes.

One of the most controversial prognostic factors is tumor burden. There is little controversy that microscopic tumor burden (nonpalpable metastatic disease) is associated with longer survival than macroscopic tumor burden (palpable metastatic disease). In our study, tumor burden was independently associated with recurrence-free but not overall survival, with a relatively small number of patients (9% of the total population) having microscopic tumor burden. What is controversial is whether this is due to a true therapeutic benefit of elective lymph node dissection or whether this merely reflects the lead-time bias associated with dissecting the nodes before they become palpable. This study or any retrospective study is not able to answer this question definitively. Large randomized controlled trials have shown benefits for only certain subgroups, 27,28 although adjuvant therapy was not uniformly used in these landmark studies. This debate has since been reshaped by sentinel lymph node biopsy; in addition to allowing for elective staging of lymph nodes with less morbidity, sentinel lymph node biopsy has improved the accuracy of lymph node staging. 13,29 The superstaging afforded by sentinel lymph node biopsy has also increased the yield of lymph node staging and created a new category of node-positive disease, reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)-positive, the significance of which is only beginning to be understood. 30–33

Patterns of Recurrence

Most patients with regional lymph node metastasis experienced some type of recurrence within 2 years of lymph node dissection. Recurrence-free survival reached a plateau after 10 years at 20%, similar to overall survival, suggesting that most patients with recurrence eventually died. However, the significant area between the recurrence-free and overall survival curves and the difference of 2 years in median recurrence-free and overall survival show that there is significant survival after recurrence.

Distant recurrence predominated as the site of first recurrence in 44% of patients overall. This is testament to the fact that tumor biology often prevailed despite complete surgical excision of local and regional disease. In 22% of patients, the first site of recurrence was local or regional, and most of these patients subsequently progressed to distant recurrence. Whether local or regional recurrence was the source of or coincident to distant recurrence in these patients cannot be determined. Conversely, when the initial site of recurrence was distant, subsequent local or regional recurrence was rare, and the “lifetime” regional recurrence rate of 14% is comparable to those rates published in other studies with large proportions of therapeutic dissections. 2,34

CONCLUSIONS

Lymph node dissection should be considered more than a staging or palliative procedure for melanoma metastatic to regional lymph nodes. The outcomes of patients with regional lymph node metastasis vary widely, with the most powerful predictor of both overall and disease-free survival after lymph node dissection being the number of positive lymph nodes. However, even patients with multiple positive lymph nodes can enjoy significant long-term survival after lymph node dissection. Therefore, aggressive surgical therapy of regional lymph node metastases is warranted, and each individual’s risk of recurrence should be weighed against the potential risks of adjuvant therapy.

Discussion

Dr. Kirby I. Bland (Birmingham, AL): President Britt, Secretary Townsend, Fellows and Guests of the Association: I wish to thank Dr. Seigler and his associates for the opportunity to discuss this signal contribution to the surgical literature from the Department of Surgery at Duke University and the Comprehensive Cancer Center database for the management of melanoma metastatic to regional nodes. This contribution is particularly meaningful because it is a prospectively collected database of over 2,500 patients with regional nodal metastasis that were treated with full lymph nodal dissection, with a follow-up of nearly 30 years. This report has provided sufficient numbers and linked follow-up to examine several important factors that pertain to long-term survival and patterns of recurrence. In this presentation, it was emphasized that LND should be considered of primacy as the principal consideration for management of this surgical disease. Thus, LND is more than a staging or palliative procedure for regional disease. While outcomes of the patients included in this database varied widely, as emphasized by the authors, the most powerful predictor of both overall and disease-free survival following lymph node dissection is the number of positive nodes. Moreover, the authors have determined that significant long-term survival is possible, even for patients with multiple, histologically positive nodal disease. I fully agree with the authors that aggressive surgical therapy of regional nodal basins metastasis is essential to provide quality of survival and long-term survival in these patients. Further, while each individual’s prognosis should be carefully evaluated relative to the various demographic features of the presentation (e.g., tumor thickness, ulceration, age, gender for patients with one or more positive lymph nodes), weighing the potential risks and benefits of adjuvant therapy is appropriate, but in virtually all cases, regional LND is requisite and appropriate to successful management. Melanoma is truly a surgical disease. I have a comment and a few questions for the authors.

Comment: As our audience is well advised, melanoma vaccines as adjuvant therapy for stage 3 disease have been associated with increased disease-free and overall survival for several phase 1/2 and early phase 3 studies. Duke and UAB surgeons have contributed to two large randomized controlled trials which at final analysis have failed to confirm significant survival benefit, and we have published the negative outcomes of this double-blind, multicenter vaccinia melanoma oncolysate trial in 1998. However, the interim analysis of ECOG-1694 comparing interferon-α to ganglioside GM2 vaccine confirmed the therapeutic advantage of inter-feron-α. In long-term follow-up of these vaccine and interferon immunotherapy trials, only certain subsets have received benefit from therapy; large impact on the survival of node-positive disease is unlikely. Biology and tumor burden remain as the extant principals of local, regional, and distant recurrence. However, the (controversial) prognostic factor, tumor burden, represents an independently associated factor for recurrence-free but not overall survival. The importance of tumor burden, comparing microscopic versus macroscopic disease, was a 7% differential in actuarial overall 5-year survival (48% vs. 41%) (P = .04). Moreover, the number of positive nodes represents a 9% difference in overall survival to move from one to two positive nodes. Thus, tumor burden, as measured by number of nodes and macroscopic presentation, is a formidable demographic consideration. Questions: In the paper a disclaimer is evident for this series as Dr. Seigler and associates have engaged in the use of experimental immunotherapy. Their data suggest that approximately 95% of patients in this series received at least one course of adjuvant specific active immunotherapy. Can the authors therefore postulate the observed (or potential) outcomes expectant with LND alone? What is the contribution of immunotherapy? Do the investigators continue to utilize the Duke-specific regimen, or interferon-α for node-positive disease? Question 2: Do the authors consider that it is the elective LND, which today can be guided by sentinel lymph node biopsy, to be the true therapeutic effect evident in this analysis? Or is this merely a reflection of the lead-time bias associated with dissection of histologically positive (clinically negative) nodes before they become palpable?

I enjoyed this paper. It is an important contribution to the literature. I thank the authors for forwarding this paper well in advance, and I thank the Association for the privilege of the floor.

Dr. Douglas R. Murray (Atlanta, GA): As Dr. Bland mentioned, the primary strength of this paper is that it represents a retrospective review of a large number of patients, 2,505, derived from 10,000 entries in the hospital over that period. These patients had regional metachronous and synchronous metastases treated at a single institution with a prospective, randomized database over a 28-year period. The series exceeds the 1,500 regionally positive patients assembled at initial staging by the Melanoma Staging Committee. Survival data are comparable, thus providing useful confirmation of the Journal of Clinical Oncology paper. This paper is also a fine testimony to the value of a well-functioning clinical database of which we are all envious. We note that the number of positive lymph nodes was the most powerful predictor of both overall survival and recurrence-free survival, with rates ranging from 53% with one positive node and 25% with greater than four nodes. Yet not all patients with single positive lymph nodes do well, nor do all patients with multiple nodes and high-risk factors do poorly. Question: Do you foresee any new molecular advances in the future to judge tumor virulence, which we so desperately need? We understand the majority of the cases consist of clinically palpable disease; however, lymph node dissection was performed in 191 patients, or 8%, and in 33 patients with sentinel lymph node biopsy with selective lymphadenectomy. The micro-tumor burden was a predictor of recurrence-free survival. It is suggested that this may represent lead-time bias. Could the conclusion be strengthened by analysis of melanoma-specific survival if it is available? Of interest, tumor burden will now be incorporated into the new AJCC staging system. It was of interest to me that in the body of the paper, which Dr. White kindly gave me, 706 patients did not undergo timely node dissections within the designated 6-week grace period. It may be interesting to know what became of them. Did they have lymph node dissection at the time of regional relapse? If their survival is comparable to the study patients, it supports the design of the Sun Belt Melanoma Trial for delayed treatment of the positive PCR patients. This may provide useful information in planning future adjuvant trials. A higher recurrence rate was also observed in the groin, 94 of 621, or 15%. My question generally relates to how does one handle the deep iliac nodes? To what extent were the deep iliac pelvic nodes responsible for the recurrence? It has been a question of one to routinely extend the dissection to include the iliac obturator lymph nodes. This may have special meaning as we move into the sentinel lymph node biopsy era—witness a case last week with intermediate thick melanoma in the leg with two positive sentinel nodes and on completion of full groin dissection has a deep positive node, and no further residual nodes in the inguinal area. Question then: How do we manage the deep nodes? Regional nodes represent site of first recurrence in only 12% of the cases, which is always very remarkable, and raise the question did any receive adjuvant radiation therapy. The most common site of recurrence was distant, as you mentioned, Dr. White, in 44%. If time allows, would you briefly state intervals of follow-up and what screening tests you think are appropriate to discover these distant sites over this long period of follow-up? Experimental adjuvant specific active immunotherapy was given to 95% of the patients, as noted by Dr. Bland. Although you feel that the favorable results achieved depend on altering the biology of the regional metastatic melanoma by adequate surgery rather than by adjuvant therapy, please speak to the future promise of the vaccine approach.

Dr. Rebekah White (Durham, NC): I will try my best to address all of your questions. I will start with Dr. Bland’s questions. It is a very important point that since over 95% of patients in this study received our adjuvant vaccine therapy that it is difficult, if not impossible, to sort out the relative effects of lymph node dissection versus adjuvant therapy. We did, since the FDA approval of interferon-α, offer patients interferon-α. But perhaps due to our heavy institutional bias and the way these options were presented to patients, fewer than 3% of the patients received interferon-α. So we are dealing with a population in which essentially all patients received our vaccine therapy. The survival rates we saw are similar or perhaps slightly better than the survival rates seen with lymph node dissection alone, but we are reluctant to attribute any difference in survival to the effect of adjuvant therapy since this was not a randomized trial. We tend to attribute the survival rates primarily to the effects of surgery.

I will start now with Dr. Murray’s questions. The point about melanoma-specific survival is a good one. We used overall survival because it is a hard-and-fast number, whereas it can be difficult to determine what is melanoma-related death. And certainly by using overall survival, we may have underestimated the prognosis of patients in this study. What we did do, though, is analyze cause of death by cohorts of survivorship. And as you might expect, people who died within 10 years of lymph node dissection were over 90% due to melanoma. With deaths after 15 years, less than 50% were related to melanoma or its treatment. We agree that the 12% recurrence rate in the regional lymph node basin is a good one, and, no, adjuvant radiation was not routinely used.

With regard to recommendations for follow-up, I think what I could suggest based on these data are that overall most recurrences occur within the first 2 years; most recurrences after that period are going to be distant, whereas most local and regional recurrences are going to occur within the first 2 years. Therefore, in the first 2 years I think close follow-up with physical exam as well as radiologic imaging is warranted. Beyond 2 years, distant recurrences predominate. But they still tend to be distant skin, distant nodes, and other things that can be detected by physical exam. So I still think that physical exam is going to be the mainstay of follow-up with these patients.

The management of deep iliac nodes. Because it was our general policy to perform therapeutic lymph node dissection only for palpable nodes, the iliac nodal basin was not routinely dissected unless those nodes were grossly involved. I agree, therefore, that that is a likely reason that local regional recurrence was higher following inguinal dissections than following axillary dissections. Another interesting finding that we discovered was that a common site of distant recurrence was actually regional basins which could be considered regional but that were not previously dissected, also supporting a role for lymphatic mapping. Finally, although the number of positive nodes was by far the most powerful predictor of survival, there clearly is not one factor that can be used to absolutely predict who will survive or who won’t survive. Further advances in the molecular staging of the lymph nodes may improve our ability to stratify these patients but are probably going to still incompletely predict the outcomes of these patients, since it is in all likelihood determined by tumor biology.

Footnotes

Correspondence: Hilliard F. Seigler, MD, Duke University Medical Center, Box 3966, Durham, NC, 27710.

E-mail: seigl001@mc.duke.edu

Presented at the 113th Annual Session of the Southern Surgical Association, December 3–5, 2001, Hot Springs, Virginia.

Accepted for publication December 2001.

References

- 1.Slingluff CL Jr, Vollmer R, Seigler HF. Stage II malignant melanoma: presentation of a prognostic model and an assessment of specific active immunotherapy in 1,273 patients. J Surg Oncol 1988; 39 (3 Suppl): 139–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calabro A, Singletary SE, Balch CM. Patterns of relapse in 1001 consecutive patients with melanoma nodal metastases. Arch Surg 1989; 124: 1051–1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bevilacqua RG, Coit DG, Rogatko A, et al. Axillary dissection in melanoma. Prognostic variables in node-positive patients. Ann Surg 1990; 212: 125–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morton DL, Wanek L, Nizze JA, et al. Improved long-term survival after lymphadenectomy of melanoma metastatic to regional nodes. Analysis of prognostic factors in 1134 patients from the John Wayne Cancer Clinic. Ann Surg 1991; 214: 491–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coit DG, Rogatko A, Brennan MF. Prognostic factors in patients with melanoma metastatic to axillary or inguinal lymph nodes. A multivariate analysis. Ann Surg 1991; 214: 627–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drepper H, Biess B, Hofherr B, et al. The prognosis of patients with stage III melanoma. Prospective long-term study of 286 patients of the Fachklinik Hornheide. Cancer 1993; 71: 1239–1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Messaris GE, Konstadoulakis MM, Ricaniadis N, et al. Prognostic variables for patients with stage III malignant melanoma. Eur J Surg 2000; 166: 233–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balch CM, Soong SJ, Gershenwald JE, et al. Prognostic factors analysis of 17,600 melanoma patients: validation of the American Joint Committee on Cancer melanoma staging system. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19: 3622–3634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seigler HF, Shingleton WW, Metzgar RS, et al. Non-specific and specific immunotherapy in patients with melanoma. Surgery 1972; 72: 162–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levy NL, Seigler HF, Shingleton WW. A multiphase immunotherapy regimen for human melanoma: clinical and laboratory results. Cancer 1974; 34 (4 Suppl): 1548–1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seigler HF, Cox E, Mutzner F, et al. Specific active immunotherapy for melanoma. Ann Surg 1979; 190: 366–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirkwood JM, Strawderman MH, Ernstoff MS, et al. Interferon alfa-2b adjuvant therapy of high-risk resected cutaneous melanoma: the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Trial EST 1684. J Clin Oncol 1996; 14: 7–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Essner R, Conforti A, Kelley MC, et al. Efficacy of lymphatic mapping, sentinel lymphadenectomy, and selective complete lymph node dissection as a therapeutic procedure for early-stage melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol 1999; 6: 442–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gershenwald JE, Thompson W, Mansfield PF, et al. Multi-institutional melanoma lymphatic mapping experience: the prognostic value of sentinel lymph node status in 612 stage I or II melanoma patients. J Clin Oncol 1999; 17: 976–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wallack MK, McNally KR, Leftheriotis E, et al. A Southeastern Cancer Study Group phase I/II trial with vaccinia melanoma oncolysates. Cancer 1986; 57: 649–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitchell MS, Harel W, Kempf RA, et al. Active-specific immunotherapy for melanoma. J Clin Oncol 1990; 8: 856–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hersey P. Evaluation of vaccinia viral lysates as therapeutic vaccines in the treatment of melanoma. Ann NY Acad Sci 1993; 690: 167–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Livingston PO, Adluri S, Helling F, et al. Phase 1 trial of immunological adjuvant QS-21 with a GM2 ganglioside-keyhole limpet haemocyanin conjugate vaccine in patients with malignant melanoma. Vaccine 1994; 12: 1275–1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsioulias GJ, Gupta RK, Tisman G, et al. Serum TA90 antigen-antibody complex as a surrogate marker for the efficacy of a polyvalent allogeneic whole-cell vaccine (CancerVax) in melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2001; 8: 198–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bystryn JC, Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A, Oratz R, et al. Double-blind trial of a polyvalent, shed-antigen, melanoma vaccine. Clin Cancer Res 2001; 7: 1882–1887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Livingston PO, Wong GY, Adluri S, et al. Improved survival in stage III melanoma patients with GM2 antibodies: a randomized trial of adjuvant vaccination with GM2 ganglioside. J Clin Oncol 1994; 12: 1036–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wallack MK, Sivanandham M, Balch CM, et al. Surgical adjuvant active specific immunotherapy for patients with stage III melanoma: the final analysis of data from a phase III, randomized, double-blind, multicenter vaccinia melanoma oncolysate trial. J Am Coll Surg 1998; 187: 69–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balch CM, Buzaid AC, Soong SJ, et al. Final version of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system for cutaneous melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19: 3635–3648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schlagenhauff B, Stroebel W, Ellwanger U, et al. Metastatic melanoma of unknown primary origin shows prognostic similarities to regional metastatic melanoma: recommendations for initial staging examinations. Cancer 1997; 80: 60–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strobbe LJ, Jonk A, Hart AA, et al. Positive iliac and obturator nodes in melanoma: survival and prognostic factors. Ann Surg Oncol 1999; 6: 255–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balch CM, Soong S, Shaw HM, et al. An anaylsis of prognostic factors in 8,500 patients with cutaneous melanoma. In: Balch CM, Houghton AN, Milton GW, et al, eds. Cutaneous melanoma. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1992: 165.

- 27.Cascinelli N, Morabito A, Santinami M, et al. Immediate or delayed dissection of regional nodes in patients with melanoma of the trunk: a randomised trial. WHO Melanoma Programme. Lancet 1998; 351 (9105): 793–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Balch CM, Soong S, Ross MI, et al. Long-term results of a multi-institutional randomized trial comparing prognostic factors and surgical results for intermediate thickness melanomas (1.0 to 4.0 mm). Intergroup Melanoma Surgical Trial. Ann Surg Oncol 2000; 7: 87–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morton DL, Thompson JF, Essner R, et al. Validation of the accuracy of intraoperative lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymphadenectomy for early-stage melanoma: a multicenter trial. Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial Group. Ann Surg 1999; 230: 453–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gershenwald JE, Colome MI, Lee JE, et al. Patterns of recurrence following a negative sentinel lymph node biopsy in 243 patients with stage I or II melanoma. J Clin Oncol 1998; 16: 2253–2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang X, Heller R, VanVoorhis N, et al. Detection of submicroscopic lymph node metastases with polymerase chain reaction in patients with malignant melanoma. Ann Surg 1994; 220: 768–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shivers SC, Wang X, Li W, et al. Molecular staging of malignant melanoma: correlation with clinical outcome. JAMA 1998; 280: 1410–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bostick PJ, Morton DL, Turner RR, et al. Prognostic significance of occult metastases detected by sentinel lymphadenectomy and reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction in early-stage melanoma patients. J Clin Oncol 1999; 17: 3238–3244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shaw JH, Rumball EM. Complications and local recurrence following lymphadenectomy. Br J Surg 1990; 77: 760–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]