Abstract

Objective

To assess the efficacy of a novel coloplasty colonic pouch design in optimizing bowel function after ultralow anterior resection.

Summary Background Data

A colonic J-pouch may reduce excessive stool frequency and incontinence after anterior resection, but at the risk of evacuation problems. Experimental surgery on pigs has suggested that a coloplasty pouch (CP) may be a useful alternative. Although CP has recently been shown to be feasible in patients, there is no randomized controlled trial comparing bowel function with the J-pouch.

Methods

After anterior resection for cancer, patients were allocated to either J-pouch or CP-anal anastomoses. Continence scoring, anorectal manometry, and endoanal ultrasound assessments were made before surgery. All complications were recorded, and these preoperative assessments were repeated at 4 months. The assessments were repeated again at 1 year, and a quality of life questionnaire was added.

Results

Eighty-eight patients were recruited from October 1998 to April 2000. Both groups were well matched for age, gender, staging, adjuvant therapy, and mean follow-up. There were no differences in the intraoperative time and hospital stay. CP resulted in more anastomotic leaks. At 4 months, J-pouch patients had 10.3% less stool fragmentation but poorer stool deferment and more nocturnal leakage. However, there were no differences in the bowel function, continence score, and quality of life at 1 year. There were no differences in the anorectal manometry and endoanal ultrasound findings.

Conclusions

Coloplasty pouches resulted in more anastomotic leaks and minimal differences in bowel function. At present, the J-pouch remains the benchmark for routine clinical practice, and due care (including defunctioning stoma) should be exercised in situations requiring CP.

Ultralow anterior resection is a well-recognized surgical technique for effective excision of mid- to low rectal cancer and also restoration of bowel continuity. However, poor bowel function may be expected with a straight coloanal anastomosis. 1,2 This includes excessive stool frequency, urgency, and incontinence. The reservoir function of the excised rectum is not adequately restored, 2,3 and there may be some damage to the anal sphincters. 2–5 In particular, the bowel function decompensates where the anastomosis is less than about 4 cm from the anal verge. 3 In such circumstances, restoration of the rectal reservoir by a colonic J-pouch results in significantly improved early function. 6 Randomized controlled trials have since confirmed the early advantages of the J-pouch, although adaptation may eventually equalize the function of straight coloanal anastomoses and J-pouches during a period of 2 years. 7–10

However, 10% to 30% of J-pouch patients may be afflicted with stool evacuation problems, such as constipation and stool fragmentation. 11,12 The use of a smaller 5- to 6-cm J-pouch (vs. a J-pouch with limbs of 10–15 cm in length) has been shown to improve stool frequency and continence without incurring severe evacuation problems. 8,13–15 A novel alternative coloplasty pouch design (CP) similar to a pyloroplasty or strictureplasty has been tried out in the experimental surgery setting in pigs. 16,17 This technique has recently been reported in patients, where the additional advantage of ease in anastomosing to the anorectal junction in a narrow pelvis was discussed. 18,19 Definite conclusions regarding its bowel function compared with the recognized J-pouch technique could not be reached because of the relatively small numbers, short follow-up, and the comparison with historical controls.

In the meantime, we conducted a randomized, controlled trial to compare bowel function after J-pouch and CP. All patients with mid- and low rectal adenocarcinomas who would normally undergo ultralow anterior resection without leaving residual local disease were included. Assessments were by bowel function questionnaire, clinical outcomes, continence scoring, quality of life measurement, anorectal manometry, and endoanal ultrasound. The study would be stopped by any emerging events that would endanger the patients’ lives or well-being.

METHODS

Patients

Consecutive patients with mid- and low rectal adenocarcinoma consented to recruitment during the 18-month period from October 1998 to April 2000, according to protocol approved by the hospital’s ethics committee. A computed tomography scan was performed to exclude those with extensive local disease, which would preclude ultralow anterior resection. Power calculations suggested that approximately 88 patients (44 per group) would be needed to identify a 30% difference in either stool frequency of 4.5 stools per day or an incontinence rate of 13%, with a power of 80% at the 5% significance level. The mean stool frequency of 4.5 stools per day and an incontinence rate of 13% had previously been reported after colonic J-pouch surgery at 6 months in our locality. 8,13–15

The patients were allocated to J-pouch and CP groups by a computer-generated code. Four specialist colorectal consultants performed the surgery. These surgeons were experienced with the J-pouch technique and had previously performed at least two CP cases without complications. Both J-pouch and CP procedures were standardized according to protocol, and the operative times were recorded. Subsequently, patients with N1 and N2, M0 lesions were offered postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy (4,500–5,000 cGy in 28 fractions over 5 weeks).

Surgical Technique

The left colon was mobilized to proximal of the splenic flexure. The inferior mesenteric artery was ligated proximal to the left colic artery, and the inferior mesenteric vein was taken at the pancreas to add tension-free length to the bowel. The rectum was dissected down to the anorectal junction at the pelvic floor, with total mesorectal excision (TME). An Autosuture PI (pneumointestinal) 30-mm transverse stapler (U.S. Surgical Corp., Norwalk, CT) was applied at or just proximal to the anorectal junction and the rectum was removed, with at least 2 cm of distal tumor clearance.

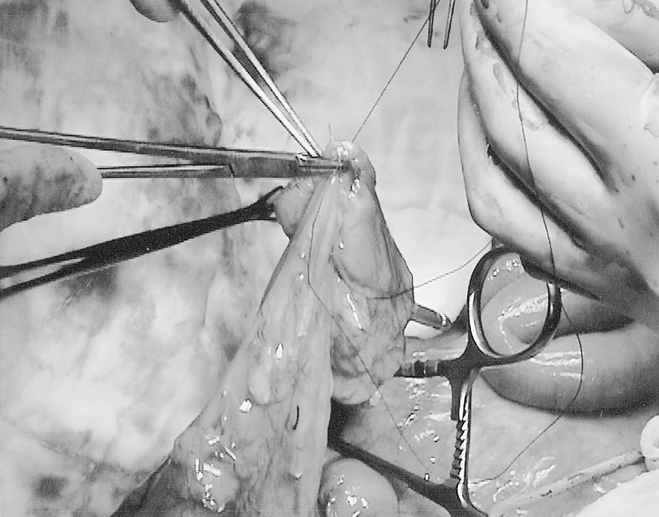

In the J-pouch group, a J-pouch was constructed from the descending colon using an Autosuture ILA (intraluminal anastomosis) 75 linear cutting stapler (U.S. Surgical Corp.), as previously described. 13 (The limbs of the pouch were measured for 6 cm before transection stapling.) The colonic J-pouch was then anastomosed to the stapled anorectal stump by a double stapling technique using an Autosuture Premium CEEA (curved end-to-end anastomosis) Plus 31 intraluminal stapler (U.S. Surgical Corp.). In the CP group, a 7-cm longitudinal incision was made between the tenia along the antimesenteric side of the descending colon, starting 4 cm above the distal cut end. The incision was closed transversely with a single layer of seromuscular 3-0 Vicryl (polyglactin; Johnson & Johnson Intl., Brussels, Belgium;Fig. 1). The coloplasty pouch was then anastomosed to the stapled anorectal stump, also by a double stapling technique with the coloplasty facing anteriorly. Both J-pouch and CP were tested with povidone-iodine insufflation. All patients were defunctioned with a loop ileostomy, which was closed after adjuvant radiotherapy if given and limited barium enema confirmation of anastomosis integrity.

Figure 1. Coloplasty pouch construction from descending colon.

Preoperative and Postoperative Assessments

Before surgery, patients were assessed with fecal continence score, anorectal manometry, and endoanal ultrasound. After surgery, routine clinical follow-up was at 3-monthly intervals. Physical examination, serum carcinoembryonic antigen levels, and colonoscopy (at 1 year) were performed to detect recurrences. Computed tomography scans and other appropriate investigations were done as indicated by the patient’s clinical condition. At 4 months, provided that the defunctioning ileostomies had been successfully closed, masked observers assessed the patients with fecal continence score, bowel function questionnaire, anorectal manometry, and endoanal ultrasound. At 1 year, the above were repeated and a quality of life questionnaire was also administered.

The fecal continence score used has been previously described and is well accepted in use. 20 Anorectal manometry was performed as previously described 3 using a microcapillary perfusion system (Synectics, Stockholm, Sweden). An experienced sonographer performed endoanal ultrasonography using a Leopard 2001 scanning system with a 10-MHz endoanal probe (B&K Medical, Standoffen, Denmark). Another experienced sonographer, who was unaware of the randomization, confirmed all findings on the printed images. The validated Fecal Incontinence Quality of Life Scale 21 was used to assess quality of life.

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS/PC+ package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Bowel function of J-pouch and CP patients was compared on an intention-to-treat basis, provided that bowel continuity was restored by ileostomy. In particular, all patients were included in the analysis regardless of complications otherwise incurred. The Fisher exact probability, Mann-Whitney, Wilcoxon, and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to test for statistical significance as appropriate.

RESULTS

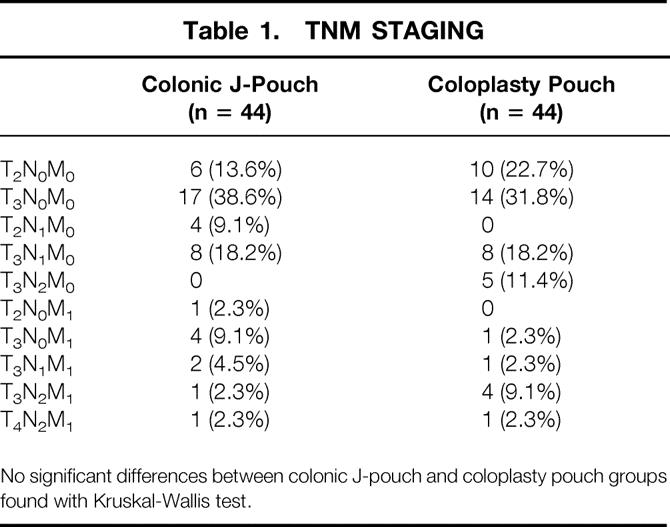

Forty-four patients were allocated to the J-pouch group. The mean age was 68.3 years (standard error of the mean [SEM] 1.2). There were 26 men (59.1%). The tumor level was a mean of 7.2 cm (SEM 0.3) above the anal verge. The TNM staging is shown in Table 1. Operative time was a mean of 143.6 minutes (SEM 30.2), and the postoperative hospital stay was a mean of 8.1 days (SEM 1.2). The mean colonic J-pouch anal anastomotic height was 3.4 cm (SEM 0.2) above the anal verge. Four patients (9.1%) with tumor involvement of the resected regional lymph nodes agreed to undergo postoperative adjuvant therapy. Diverting ileostomies were closed at a mean of 7.9 weeks (SEM 2.1; median 5, range 3–16) after the ultralow anterior resection. Mean follow-up to date was 17.3 months (SEM 1.2).

Table 1. TNM STAGING

No significant differences between colonic J-pouch and coloplasty pouch groups found with Kruskal-Wallis test.

Another 44 patients were allocated to the CP group. The mean age was 65.4 years (SEM 1.6) years. There were 27 men (38.6%). The tumor level was a mean of 7.6 cm (SEM 0.4) above the anal verge, and the TNM staging is shown in Table 1. Operative time was a mean of 110 minutes (SEM 5.2), and the postoperative hospital stay was 9.5 days (SEM 1). The mean coloplasty pouch anal anastomotic height was 3.2 cm (SEM 0.3) above the anal verge. Sixteen patients (36.4%) agreed to undergo postoperative adjuvant therapy. Diverting ileostomies were closed at a mean of 8.6 weeks (SEM 1.4; median 5, range 2–24) after the resection. Mean follow-up to date was 17 months (SEM 1.4).

There were no significant differences in distributions of patient age, gender, tumor level, TNM staging, intraoperative time, postoperative hospital stay, anastomotic height, adjuvant therapy, time to ileostomy closure, and mean follow-up between the two groups.

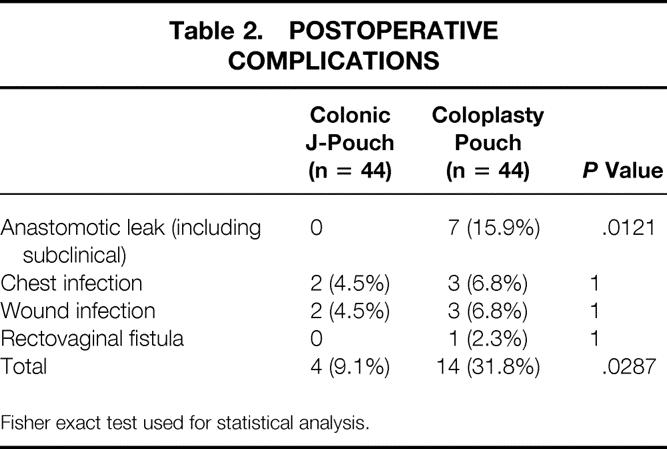

Postoperative complications were significantly higher in the CP group, and this was due to the much higher anastomotic leak rates (Table 2). One of the anastomotic leaks required laparotomy for peritonitis and two required transrectal drainage for well-localized abscesses. The remaining four were asymptomatic and detected only on routine barium enema before considering ileostomy closure. All the leaks were at the anterior of the coloanal anastomoses, below the site of the coloplasty. Anastomotic leaks were not significantly associated with postoperative chemotherapy or radiotherapy (P = .417).

Table 2. POSTOPERATIVE COMPLICATIONS

Fisher exact test used for statistical analysis.

Death before hospital discharge occurred in one CP patient (2.3%) as a result of chest infection. Hence, at 4 months after surgery, 39 patients in the CP group were available for functional assessments because three ileostomies (where dehiscence had occurred) remained unclosed. At 1 year after surgery, 32 patients from the J-pouch group and 36 from the CP group were available for functional assessments. In the J-pouch group, 12 patients (27.3%) had died because of residual cancer in 9 and recurrences in another 3. Recurrences had occurred in 4 of 35 (11.4%) curative resections in this group (liver n = 2, liver and peritoneal n = 1, pelvic n = 1). In the CP group, death had occurred in another six patients because of residual cancer (making a total of 7, 15.9%). Recurrences occurred in 3 of 37 (8.1%) curative resections in this group (liver n = 2, iliac node n = 1). In the meantime, a further two of the outstanding ileostomies were closed. The only complication from all ileostomy closures was a wound infection in the CP group (2.5%;P = .4699).

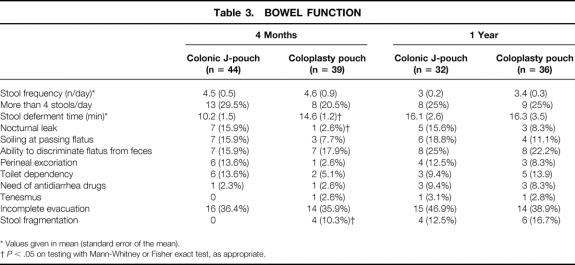

Bowel function at 4 months was different between J-pouch and CP patients. Patients with coloplasty pouches were able to defer their bowel movements better and had less nocturnal leaks, but there was more stool fragmentation (Table 3). However, bowel function equalized in both groups such that no significant differences were noted at 1 year. Where the ileostomies were closed in patients with anastomosis dehiscence, bowel function was not worse than others in the CP group. This may be related to the small size of the leaks and early treatment where clinically indicated.

Table 3. BOWEL FUNCTION

* Values given in mean (standard error of the mean).

†P < .05 on testing with Mann-Whitney or Fisher exact test, as appropriate.

No significant differences were found in the continence and quality of life scoring between groups. There were no significant differences in the continence scores either before surgery (J-pouch mean 0.7 [SEM 0.3], CP 3 [1];P = .45) or at 4 months (J-pouch mean 1.8 [SEM 0.6], CP 3.2 [1];P = .583) or 1 year after surgery (J-pouch mean 1.3 [SEM 0.4], CP 3.2 [1.2];P = .36). Preoperative incontinence was due to five J-pouch and four CJ patients with various degrees of occasional liquid staining. However, the change from the preoperative value was not different between groups at either 4 months (P = .585) or 1 year (P = .487). At 1 year, quality of life scoring showed no differences between groups for the various scales: lifestyle (J-pouch mean 3.5 [SEM 0.2], CP 3 [0.3];P = .106), coping/behavior (J-pouch 3.5 [0.2], CP 3 [0.2];P = .154), depression/self-perception (J-pouch 3.6 [0.2], CP 3.2 [0.2];P = .140), and embarrassment (J-pouch 3.6 [0.2], CP 3.2 [0.3];P = .423).

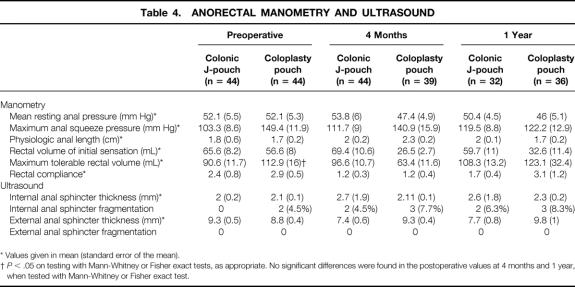

There were no salient differences in the anorectal manometry and endoanal ultrasound findings between the two groups (Table 4). The preoperative maximum tolerable volume in the CP patients was greater, but there were no differences after surgery, and the postoperative changes were not different between groups. The rectosphincteric inhibitory reflex was present in all patients before surgery. Postoperative changes were not different between groups at 4 months (J-pouch rectosphincteric reflex present n = 15 [34.1%], CP n = 14 [31.8%];P = 1) and 1 year (J-pouch n = 14 [43.8%], CP n = 16 [44.4%];P = 1). Two CP patients had occult internal sphincter fragmentations, probably related to previous obstetric history. The postoperative changes were not significantly different between J-pouch and CP patients.

Table 4. ANORECTAL MANOMETRY AND ULTRASOUND

* Values given in mean (standard error of the mean).

†P < .05 on testing with Mann-Whitney or Fisher exact tests, as appropriate. No significant differences were found in the postoperative values at 4 months and 1 year, when tested with Mann-Whitney or Fisher exact test.

DISCUSSION

Our most salient finding was significantly more anastomotic leaks (15.9%) in the CP patients. Seven percent were clinical and 9% were radiologic. A 5% incidence of clinical anastomotic leak was reported in the only other series on CP patients (nonrandomized) to date. 19 Hallböök et al. 7 reported a randomized trial comparing J-pouch with straight coloanal anastomosis. The J-pouch patients had significantly fewer clinical anastomotic leaks (2% vs. 15%;P = .03). Other comparison studies, not all randomized, have reported a clinical anastomotic leak rate ranging from 0% to 4.9% after CP and 0% to 17% after straight coloanal anastomosis. 8,9,13,14,22,23 The lower incidence of anastomotic leak after J-pouch may be due to better proximal anastomotic blood supply, as shown by the laser Doppler technique. 24 This better blood supply at the critical anastomotic site was related to the J-pouch being anastomosed side-to-end to the anal canal, compared with the straight coloanal, which was an end-to-end anastomosis. Hence, our higher leak rates after CP may be due essentially to the coloanal anastomosis being made end-to-end, as in the straight coloanal anastomoses. Our CP leak rates were comparable to the straight anastomosis leak rates mentioned above. Unfortunately, we were not able to ascertain this because there was no straight anastomosis arm in our study protocol. An additional possibility to consider would be some compromise of blood supply to the colonic anastomotic end as a result of the coloplasty. This may account for all the clinical and radiologic leaks occurring anteriorly at the coloanal anastomosis, just distal to the coloplasty. However, all the edges of the incision appeared viable, often with brisk bleeding at the time of coloplasty suturing. Further, there was no clinical evidence of compromise in the bowel distal to the coloplasty, before coloanal anastomosis. Nonetheless, if subtle but significant vascular compromise can be proven, it would have important implications for refining the design of the coloplasty pouch (such as varying the distance of the coloplasty incision from the distal margin). It was unlikely that the CP anastomotic leaks were the result of a learning curve because the leaks were distributed evenly throughout the period of the study. Further, the demographics of the J-pouch and CP patients were well matched. In particular, none of the CP dehiscence patients had received any postoperative radiotherapy or chemotherapy.

The different colonic pouch techniques resulted in subtle early differences in bowel function. J-pouch patients had significantly less stool fragmentation, which required returning to the toilet at least once within 15 minutes of evacuation. However, both groups of patients reported increased stool fragmentation at 1 year. It is known that patients may have difficulty in differentiating stool fragmentation from increased bowel frequency. 10 Hence, further studies are required to confirm these findings. No differences were found with other stool evacuation problems. Minimal evacuation problems have been reported with the smaller 5- to 6-cm J-pouch compared with the larger versions. 8,13,14,25–29 This may be related to the ambulatory anorectal physiologic findings of large contraction waves when the J-pouch size is excessive. 14,30 However, the CP patients had significantly better stool deferment time and less nocturnal liquid stool leakage. No differences were found with other stool incontinence symptoms and with continence scoring. Bowel function in the J-pouch group was comparable to results we have previously reported in our patients. 8,13–15 The only published study on the CP technique compared 20 patients with historical controls consisting of 16 J-pouch and 17 straight coloanal anastomoses. 19 There were no significant differences between CP and J-pouch patients when stool frequency, use of antidiarrheal medication, and continence were compared. This was similar to our findings at 1 year of follow-up, where no differences were found in bowel function. It appeared that adaptation occurred in the CP, probably similar to that previously reported with J-pouch and straight coloanal anastomoses. 8–10,22 As mentioned above, the J-pouch and CP groups were well matched, and therefore bowel function was unlikely to be confounded by factors such as adjuvant therapy, 31 age, use of antidiarrheal medications, or local cancer recurrences. Although not statistically significant, more patients in the CP group received postoperative chemoradiotherapy. It may be possible that larger numbers from further studies would show CP bowel function to be more resistant to the effects of adjuvant therapy. Patients with anastomotic leaks did not have poorer function, probably because the vast majority of leaks were radiologic or otherwise minor. Hence, ensuing bowel function would minimally influence the choice for either J-pouch or CP, and the patients’ perceptions as measured by the Fecal Incontinence Quality of Life scale confirmed this.

The anorectal manometric findings did not show any significant differences in the function of the different colonic pouches. Colonic pouch reservoir function, as measured by the rectal volume of initial sensation, maximum tolerable volume, and compliance, was not different between the groups. This was consistent with the findings of Mantyh et al., 19 mentioned above. Z’graggen et al. 16 also found no differences in maximum tolerable volume and compliance between J-pouch and CP in their experimental surgery on 15 pigs. Although studies on larger J-pouches have shown improved rectal reservoir function over straight coloanal anastomoses, 29,32 these improvements have not been confirmed in smaller 6-cm J-pouches despite improvements in bowel function. 8,13–15 Nonetheless, ambulatory manometric studies have confirmed improved anorectal pressure gradients in the 6-cm J-pouch. 14 Scintigraphy studies in such a J-pouch design have also shown improved retention of liquids, rather than solid feces, which might account for improved stool frequency and continence with minimal evacuation problems. 15 It was suggested that motility factors such as reversed peristalsis may account for such findings in small 6-cm J-pouches. 13,15 Although experimental surgery construction of a CP may provide a 40% increase in volume, 17 it is more likely that in the clinical situation motility factors such as disruption of colonic propulsion as a result of the coloplasty on the antimesenteric surface may be more important. 19

Endoanal ultrasound anal sphincter injuries were found in 4% to 6% of our patients. This incidence was consistent with previous reports of such injuries caused by transanal introduction of a stapling device. 4,5,33,34 Most of these reported sphincter injuries were asymptomatic, and very few were severe enough to require surgery. Because the incidence was evenly distributed between both our J-pouch and CP patients, it was unlikely to have confounded the bowel function.

As already mentioned, it was not known whether the higher anastomotic leak rate with CP was similar to that of straight coloanal anastomoses or uniquely due to the pouch design. A straight coloanal anastomosis arm was not incorporated into our randomized controlled study protocol. This was because the increased anastomotic leak rate was a surprise finding for a study originally designed primarily to compare bowel function. Quite conclusive evidence is currently available to support the J-pouch as the technique of choice that provides superior bowel function in the early postoperative period. 8–10,22 Therefore, from the bowel function aspect, it was considered unnecessary to recruit a further large number of patients to benchmark against a straight coloanal anastomosis arm, which has proven to be less effective.

Another possible shortcoming of our study is the relatively short follow-up of 1 year. However, it is unlikely that further long-term complications or problems in bowel function may arise de novo.

In summary, we found that the novel CP resulted in a higher incidence of anastomotic leaks compared with the J-pouch. However, the leak rates were comparable to those previously reported after straight coloanal anastomoses. The bowel function was not much different, especially at 1 year. The patients’ quality of life scoring was similar between both groups. Anorectal manometry and endoanal ultrasound findings were also similar. Hence, at this time, we cannot recommend the CP except for special circumstances when a bulky J-pouch cannot be brought through a narrow pelvis for anastomosis to the anorectal junction. However, this situation did not occur in our present study, and no patient needed to have the procedure that had been allocated before surgery changed for technical reasons. Nonetheless, further studies with variations in CP design and longer follow-up may reveal other advantages in the technique. However, due caution, including the use of defunctioning stoma and careful postoperative observation, should be exercised because of the higher risks of anastomosis dehiscence shown.

Footnotes

Correspondence: Prof. Yik-Hong Ho, Discipline of Surgery, School of Medicine, James Cook University, Townsville, Qld 4811, Australia.

E-mail: yik-hong.ho@bigpond.com

Accepted for publication December 4, 2001.

References

- 1.Ho Y-H, Low D, Goh HS. Bowel function survey after segmental colorectal resection. Dis Colon Rectum 1996; 38: 307–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williamson ME, Lewis WG, Holdsworth PJ, et al. Decrease in anorectal pressure gradient after low anterior resection of the rectum: a study using continuous ambulatory manometry. Dis Colon Rectum 1994; 37: 1228–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ho Y-H, Wong J, Goh HS. Level of anastomosis and anorectal manometry in predicting function following anterior resection for adenocarcinoma. Int J Colorect Dis 1993; 8: 170–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ho Y-H, Tsang C, Tang CL, et al. Anal sphincter injuries from stapling instruments introduced transanally. Randomized, controlled study with endoanal ultrasound and anorectal manometry. Dis Colon Rectum 2000; 43: 169–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ho Y-H, Tan M, Leong A, et al. Anal pressures impaired by stapler insertion during colorectal anastomosis: a randomized, controlled trial. Dis Colon Rectum 1999; 42: 89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hida J, Yasutomi M, Maruyama T, et al. Indications for colonic J-pouch reconstruction after anterior resection for rectal cancer: determining the optimum level of anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum 1998; 41: 558–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hallböök O, Pahlman L, Krog M, et al. Randomized comparison of straight and colonic J pouch anastomosis after lower anterior resection. Ann Surg 1996; 224: 58–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ho Y-H, Seow-Choen F, Tan M. Colonic J-pouch function at six months versus straight coloanal anastomosis at two years: randomized controlled trial. World J Surg 2001; 25: 876–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lazorthes F, Chiotasso P, Gamagami RA, et al. Late clinical outcome in a randomized prospective comparison of colonic J pouch and straight coloanal anastomosis. Br J Surg 1997; 84: 1449–1451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dehni N, Tiret E, Singland JD, et al. Long-term functional outcome after low anterior resection: comparison of low colorectal anastomosis and colonic J-pouch-anal anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum 1998; 41: 822–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berger A, Tiret E, Parc R, et al. Excision of the rectum with colonic J pouch-anal anastomosis for adenocarcinoma of the low and mid rectum. World J Surg 1992; 16: 470–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pelissier EP, Blum D, Bachour A, et al. Functional results of coloanal anastomosis with reservoir. Dis Colon Rectum 1992; 35: 843–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ho Y-H, Tan M, Seow-Choen F. Prospective randomized controlled study of clinical function and anorectal physiology after low anterior resection: comparison of straight and colonic J pouch anastomoses. Br J Surg 1996; 83: 978–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ho Y-H, Tan M, Leong A, et al. Ambulatory manometry in patients with colonic J-pouch and straight coloanal anastomoses: randomized, controlled trial. Dis Colon Rectum 2000; 43: 793–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ho Y-H, Yu S, Ang E-S, et al. Small colonic J-pouch improves colonic retention of liquids—randomized controlled trial with scintigraphy. Dis Colon Rectum 2002; 45: 76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Z’graggen K, Maurer CA, Mettler D, et al. A novel colon pouch and its comparison with a straight coloanal J-pouch anastomosis: preliminary results in pigs. Surgery 1999; 125: 105–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maurer CA, Z’graggen K, Zimmermann W, et al. Experimental study of neorectal physiology after formation of transverse coloplasty pouch. Br J Surg 1999; 86: 1451–1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fazio VW, Mantyh CR, Hull TL. Colonic. “coloplasty”: novel technique to enhance low colorectal or coloanal anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum 2000; 43: 1448–1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mantyh CR, Hull TL, Fazio VW. Coloplasty in low colorectal anastomosis: manometric and functional comparison with straight and colonic J-pouch anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum 2001; 44: 37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jorge JM, Wexner SD. Etiology and management of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 1993; 36: 77–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rockwood TH, Church JM, Fleshman JW, et al. Fecal incontinence quality of life scale. Quality of life instrument for patients with fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 2000; 43: 9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joo JS, Latulippe JF, Alabaz O, et al. Long-term functional evaluation of straight coloanal ansotomosis and colonic J-pouch. Dis Colon Rectum 1998; 41: 740–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dehni N, Schlegel RD, Cunningham C, et al. Influence of a defunctioning stoma on leakage rates after low colorectal anastomosis and colonic J pouch-anal anastomosis. Br J Surg 1998; 85: 1114–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hallböök O, Johansson K, Sjödahl R. Laser Doppler blood flow measurement in rectal resection for carcinoma—comparison between the straight and colonic J pouch reconstruction. Br J Surg 1996; 83: 389–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chew SN, Tindal DS. Colonic J-pouch as a neorectum: functional assessment. Aust NZ J Surg 1997; 67: 607–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hallböök O, Sjödahl R. Comparison between the colonic J pouch-anal anastomosis and healthy rectum: clinical and physiological function. Br J Surg 1997; 84: 1437–1441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lazorthes F, Gamagami R, Chiotasso P, et al. Prospective, randomized study comparing clinical results between small and large colonic J-pouch following coloanal anstomosis. Dis Colon Rectum 1997; 40: 1409–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hida J, Yasutomi M, Fujimoto K, et al. Functional outcome after low anterior resection with low anastomosis for rectal cancer using the colonic J-pouch. Prospective randomized study for determination of optimum pouch size. Dis Colon Rectum 1996; 39: 986–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ortiz H, De Miguel M, Armendariz P, et al. Coloanal anastomosis: are functional results better with a pouch? Dis Colon Rectum 1995; 38: 375–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Romanos J, Stebbing JF, Smilgin Humphreys MM, et al. Ambulatory manometric examination in patients with a colonic J pouch and in normal controls. Br J Surg 1996; 83: 1774–1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ho Y-H, Lee KS, Nyam D, et al. Effects of adjuvant radiotherapy on bowel function and anorectal physiology, after low anterior resection for rectal cancer. Tech Coloproct 2000; 4: 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hallböök O, Nyström P-O, Sjödahl R. Physiologic characteristics of straight and colonic J-pouch anastomoses after rectal excision for cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 1997; 40: 332–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ho Y-H. Postanal sphincter repair for anterior resection anal sphincter injuries—report of three cases. Dis Colon Rectum 2001; 44: 1218–1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farouk R, Duthie GS, Lee PW, et al. Endosonographic evidence of injury to the internal anal sphincter after low anterior resection: long-term follow-up. Dis Colon Rectum 1998; 41: 888–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]