Abstract

Objective

To investigate local inflammatory events within the colonic muscularis as a causative factor of postoperative ileus.

Summary Background Data

Surgically induced intestinal muscularis inflammation has been hypothesized as a mechanism for postoperative ileus. The colon is a crucial component for recovery of gastrointestinal motor function after surgery but remains unaddressed. The authors hypothesize that colonic manipulation initiates inflammatory events that directly mediate postoperative smooth muscle dysfunction.

Methods

Rats underwent colonic manipulation. In vivo transit and colonic motility was estimated using geometric center analysis and intraluminal pressure monitoring. Leukocyte extravasation was investigated in muscularis whole mounts. Mediator mRNA expression was determined by real-time reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction. In vitro circular muscle contractility was assessed in a standard organ bath. The relevance of iNOS and COX-2 inhibition was determined using DFU or L-NIL perfusion.

Results

Colonic manipulation resulted in a massive leukocyte recruitment and an increase in inflammatory mRNA expression. This inflammatory response was associated with an impairment of in vivo motor function and an inhibition of in vitro smooth muscle contractility (56%). L-NIL but not DFU significantly ameliorated smooth muscle dysfunction.

Conclusions

The results provide evidence for a surgically initiated local inflammatory cascade within the colonic muscularis that mediates smooth muscle dysfunction, which contributes to postoperative ileus.

Iatrogenic postoperative gastrointestinal dysmotility remains a near- canonical outcome of abdominal surgery. The occurrence of ileus-related complications as well as the “typical” delayed postoperative recovery of intestinal motor activity is associated with a prolonged hospital stay and increased perioperative expense, which has a significant economic impact. 1–3

Inhibitory neural reflexes and local inflammatory events within the intestinal muscularis have been proposed to participate in the development of postoperative motility changes. 2,4,5 We have previously shown that surgical manipulation of the small intestine results in the activation of resident muscularis macrophages, which is followed by a massive extravasation of immunocompetent cells into the intestinal muscularis. 5 This inflammatory response correlates with the postoperative suppression in jejunal smooth muscle contractile activity. 6 However, the resumption of gastrointestinal motility is dependent on the functional cooperation of the entire gastrointestinal tract, and the recovery of the small intestine may arguably not be the crucial gastrointestinal component of surgically induced ileus. 1 The duration of postoperative ileus appears region-specific and may be most persistent in the colon. 3,7 In this regard the colon could act as a downstream barrier so that the return of colonic activity may be the most significant factor for the recovery of gastrointestinal motor function. The underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms for colonic ileus are still largely unknown, and the inflammatory events within the colonic muscularis have not yet been investigated.

Activated resident muscularis macrophages have been hypothesized as the initiators of the critical inflammatory events that result in a subsequent suppression in small intestinal motility in rodent models of postoperative and endotoxemic ileus. 5,8 It has also been demonstrated that a dense network of resident macrophages populates the muscularis externa of the entire gastrointestinal tract. 9 The postoperative activation of the macrophage network in the small intestine initiates leukocyte recruitment. 10 In the environment of this inflammatory milieu, the activated resident as well as recruited leukocytes liberate kinetically active substances, such as NO and prostanoids, resulting in postoperative dysmotility. 11,12 Based on these previous observations, we developed the hypothesis that surgical manipulation of the colon initiates a similar local molecular and cellular inflammatory response. Further, we speculate that this colonic muscularis inflammation causes the expression of kinetically active mediators that directly modulate colonic smooth muscle contractile activity. Therefore, our objectives were to verify the postoperative recruitment of immunocompetent cells into the colonic muscularis, determine and delineate the time course of inflammatory mediator mRNAs within the colonic muscularis, define the in vivo and in vitro functional relevance of colonic muscularis inflammation, and determine the potential ameliorative effects of specific pharmacologic mediator inhibition on smooth muscle dysfunction caused by colonic manipulation.

METHODS

Animals

Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 180 to 220 g were obtained from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN). The experimental design was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All animals were kept in a pathogen-free facility that is accredited by the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care and that complies with the requirements of humane animal care as stipulated by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Department of Health and Human Services. They were maintained on a 12-hour light/dark cycle and provided with standard laboratory rat chow and tap water ad libitum.

Operative Procedure

The rat colon was subjected to a standardized degree of surgical manipulation. All operative procedures were performed under sterile conditions, with the intestine being handled only by instruments and never touched directly. Rats were anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation, and the abdomen was opened by a midline laparotomy. The cecum was eventrated and laid out onto a moist gauze. The colon was inspected along its whole length and gently compressed using moist cotton applicators. In a second series of experiments, animals were additionally subjected to a standardized surgical manipulation of the entire intestine. In sham operations, the abdomen was opened by a midline laparotomy and the cecum was eventrated and laid out onto a moist gauze without performing the colonic compression. To define the time course of gene expression within the isolated colonic muscularis, animals were killed at specific time points (3, 6, and 18 hours) after surgery by isoflurane anesthesia inhalation overdose (n = 4 each). 10 For functional and immunohistochemical studies, rats were killed 24 hours after surgery. Age-matched unoperated rats served as controls. All animals recovered rapidly from surgery without complications and with no deaths.

Quantification of Gene Expression

The time course of postoperative mediator mRNA expression was analyzed using SYBR Green two-step real-time reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Total mRNA extraction was performed as previously described using the guanidinium-thiocyanate phenol-chloroform extraction method. 8 The RNA pellets were resuspended in RNAsecure resuspension solution (Ambion Inc., Austin, TX). After the resuspension, a DNase treatment was carried out (DNA-free reagent, Ambion Inc.). Then, equal aliquots (200 ng) of total RNA from each sample, quantified by spectrophotometry, were processed for complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis.

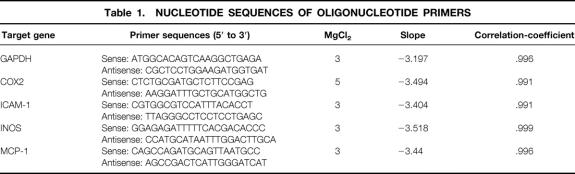

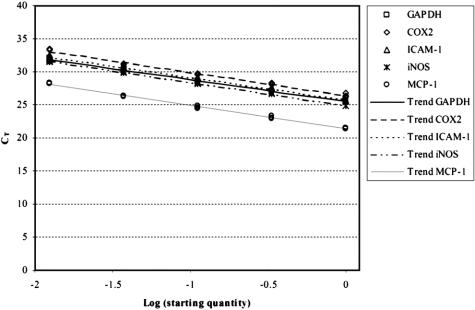

Primers were designed according to published sequences, 13–17 or using Primer Express software (PE Applied Biosystems) and purchased from Life Technologies (Rockville, MD). GAPDH was used as an endogenous control. The sequences of the real-time PCR primers are listed in Table 1. The efficiency and equality of the real-time PCR primer pairs were determined by amplifying serial dilutions of colonic muscularis cDNA (Fig. 1). For each target gene different MgCl2 (3–5 mmol/L) concentrations were tested to optimize the PCR amplification. Agarose gel electrophoretic analysis was used to verify the presence of a single product and to ensure that the amplified product corresponded to size predicted for the amplicon. Each sample was estimated in triplicate. The PCR reaction mixture was prepared using the SYBR Green PCR Core Reagents (PE Applied Biosystems). PCR conditions on an ABI PRISM 7700 Sequence Detection System (PE Applied Biosystems) were as recommended by the manufacturer. Relative quantification was performed using the comparative CT method as described previously by Schmittgen et al. 18 (see also User Bulletin #2, PE Applied Biosystems).

Table 1. NUCLEOTIDE SEQUENCES OF OLIGONUCLEOTIDE PRIMERS

Figure 1. Efficiency of SYBR Green real-time polymerase chain reaction amplification of target gene expression was tested on serial dilutions of rat colonic muscularis cDNA. The figure shows the linear relationship between the threshold cycle (CT) and log starting quantity of rat colonic muscularis cDNA. Coamplification of GAPDH (endogenous control) and the target genes (COX-2, ICAM-1, iNOS, and MCP-1) revealed parallel trend curves, showing almost identical primer efficiencies.

Histochemistry and Immunohistochemistry

Histochemical and immunohistochemical analysis was performed on whole mounts of the intestinal muscularis as described previously (n = 5 each). 9 Myeloperoxidase-positive cells were detected using a mixture of 20 mg Hanker-Yates reagent (Polysciences, Warrington, PA), 20 mL KRB, and 200 μL 3% hydrogen peroxide (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) for 10 minutes. ED1-immunohistochemistry was used to visualize monocytes. Whole mounts were incubated overnight at 4°C in an ED1-antibody solution (mouse-antirat, 1:100), followed by 3× washes in 0.05 mol/L phosphate-buffered saline solution (PBS). Each specimen was then incubated with a Cy3 donkey-antimouse secondary antibody (1:500) for 4 hours at 4°C and washed again three times in 0.05 mol/L PBS. Secondary antibodies without ED1 antibody preincubation were used in parallel in all staining procedures to ensure specificity. Leukocytes were counted in five randomly chosen areas in each specimen (three specimens per animal) at a magnification of 200×.

Functional Studies

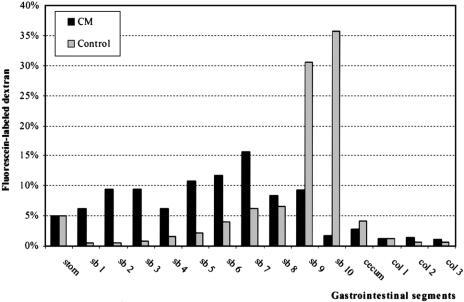

In vivo intestinal transit was measured in unoperated and in manipulated animals at 24 hours after surgery by evaluating the intestinal distribution of orally administered fluorescein-labeled dextran (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR; molecular weight = 70,000) as previously described (n = 5 each). 6 The data were expressed as the percentage of activity per segment and plotted on a histogram. Gastrointestinal transit was calculated as the geometric center (GC) of distribution of fluorescein-labeled dextran using the following formula: GC = Σ(% of total fluorescent signal per segment * segment number)/100. The GC value reflects the transit of fluorescently labeled dextran down the gastrointestinal tract, with higher values indicating more distal distribution (segment 1 = stomach to segment 15 = distal colon).

Distal colonic in vivo motility was recorded in awake, restrained rats 24 hours after colonic manipulation or sham operations (n = 5 each) with an intracolonic balloon-tipped catheter, as previously described. 19 Pressures were recorded and analyzed using the MacLab data acquisition package (ADInstruments Pty. Ltd., Castle Hill, Australia) and a Macintosh G3 computer. After a 20- to 30-minute period of acclimatization, animals underwent recording for periods of 2 to 3 hours.

In separate experiments, mechanical in vitro activity of the midcolon was evaluated using smooth muscle strips of the circular muscularis as described previously for the jejunum (n = 5 each). 5 After recording spontaneous contractility for 30 minutes, dose-response curves were generated using increasing doses of the muscarinic agonist bethanechol (1–300 μmol/L) for 10 minutes and intervening wash periods (KRB) of 10 minutes. The contractile response was recorded and analyzed as gram/mm2/s.

The functional significance of COX-2 and iNOS inhibition was determined by measuring changes of in vitro colonic circular muscle contractility in response to the selective COX-2 inhibitor DFU (5,5-dimethyl-3-(3-fluorophenyl)-4-(4-methylsulfonyl)phenyl-2(5H)-furanone: 5 mg/L) or the iNOS inhibitor L-NIL (L-N6-(1-iminoethyl)-lysine dihydrochloride: 30 μmol/L), respectively. 11,20

In another series of functional in vitro experiments, animals were subjected to a combined small intestinal and colonic manipulation (n = 5 each). 5 Two adjacent muscle strips were taken from the midcolon and the midjejunum of each animal. After equilibration and recording of spontaneous contractility for 30 minutes, muscle strips were superfused simultaneously with DFUL, NIL, or KRB for another 30 minutes.

Drugs and Solutions

A standard KRB was used as described previously. 6,9 KRB constituents and bethanechol were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. The COX-2 inhibitor DFU was kindly provided by Merck Frosst (Quebec, Canada) and the iNOS inhibitor L-NIL was purchased from Alexis Corp. (San Diego, CA). Mouse-antirat-ED1 antibodies (1:100) were obtained from Serotec Inc. (Raleigh, NC). Indocarbocyanine (Cy3)-conjugated donkey-antimouse antibody (1:500) was purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc. (West Grove, PA).

Data Analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analysis was performed using a Student t-test (paired for the COX-2 and iNOS inhibition experiments and unpaired for all other experiments). A probability level of P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Postoperative Impairment of In Vivo and In Vitro Gastrointestinal Motility After Colonic Manipulation

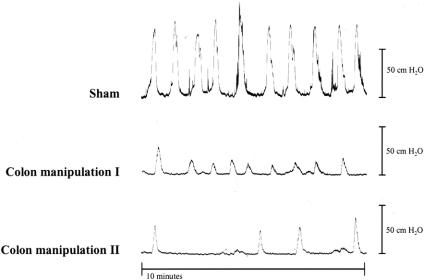

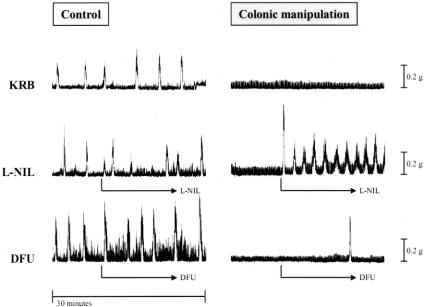

To directly investigate postoperative in vivo colonic function, we performed intracolonic pressure recordings. A representative distal colonic pressure recording 24 hours after sham operation is illustrated in Figure 2. Note the symmetric pattern of the contractions and the regularity in contractile frequency. For this group, the amplitude of the distal colonic contractions averaged 98 ± 3 cm H2O, and the large contractile frequency averaged 0.8 ± 0.1 per minute. Twenty-four hours after colonic manipulation, colonic contractile amplitudes were markedly diminished (by >50%) and more variable in amplitude and frequency (see Fig. 2). The mean contractile amplitude for this group was significantly reduced to 41 ± 14 cm H2O compared with the sham-operated group. Colonic contractile frequencies were also significantly slower (0.3 ± 0.1 per minute) in these animals.

Figure 2. Representative distal colonic pressure recordings obtained from one sham-operated and two colon-manipulated animals 24 hours after surgery. Colonic manipulation causes a reduction in contraction amplitude and frequency.

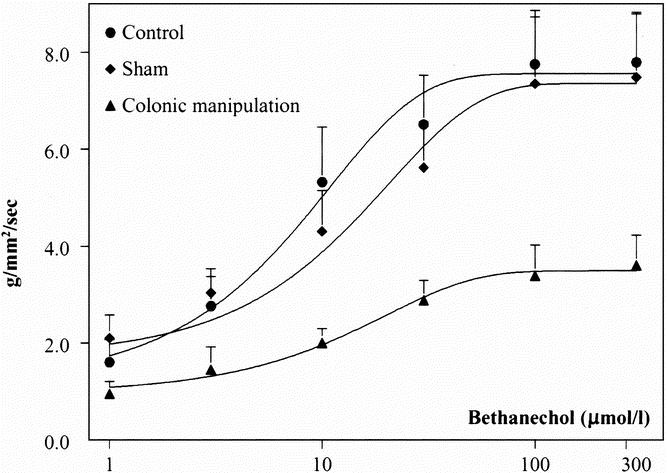

In the next series of experiments, the capacity of the colonic circular muscularis to respond to the cholinergic agonist bethanechol was determined 24 hours after surgery using standard organ bath techniques in vitro. As illustrated in Figure 3, perfusion with bethanechol caused a dose-dependent increase in the generation of contractile activity, which was reduced in the muscle strips from manipulated animals. Midcolonic circular muscle strips from control animals generated contractions with a mean contractile force of 7.8 ± 1.1 g/mm2/s at 100 μmol/L bethanechol. Sham-operated animals presented with a contractile response to bethanechol similar to control animals (contractile force of 7.4 ± 1.4 g/mm2/s at 100 μmol/L), whereas muscle strips from surgically manipulated segments showed an impairment in the bethanechol-stimulated dose-response curve (contractile force of 3.4 ± 0.6 g/mm2/s at 100 μmol/L).

Figure 3. Bethanechol dose-response curves, showing impairment in circular smooth muscle contractile activity after colonic manipulation. The contractility in response to the muscarinic agonist bethanechol (1, 3, 10, 100, and 300 μmol/L) was measured in midcolonic muscle strips from control, sham-operated, and colon-manipulated animals. The bethanechol-stimulated contractility in animals subjected to colonic manipulation was reduced by 53.9% compared with sham animals at a bethanechol concentration of 100 μmol/L.

Clinically, motility changes frequently occur in regions of the gastrointestinal tract other than the one directly operated on. Indeed, in this model 24 hours after selective colonic manipulation a significant transit delay was observed in the small intestine compared with control, with an almost uniform distribution of the fluorescent marker along the entire small intestine (GC = 6.5 ± 0.7). In control animals, in vivo transit of the nonabsorbable fluorescent marker accumulated in the last two distal segments of the small intestine 2 hours after oral administration, displaying a calculated GC of 9.5 ± 0.3 (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Transit histogram for the distribution of nonabsorbable fluorescein-labeled dextran along the gastrointestinal tract 2 hours after oral administration. CM, colonic manipulation; stom, stomach; sb, small bowel; col, colon. In control animals (light-gray bars), the nonabsorbable marker accumulated in the last two segments of the intestine (sb 9 and sb 10). Colonic manipulation (dark-gray bars) caused a significant delay in intestinal transit.

Cellular Inflammatory Events Within the Intestinal Muscularis After Colonic Manipulation

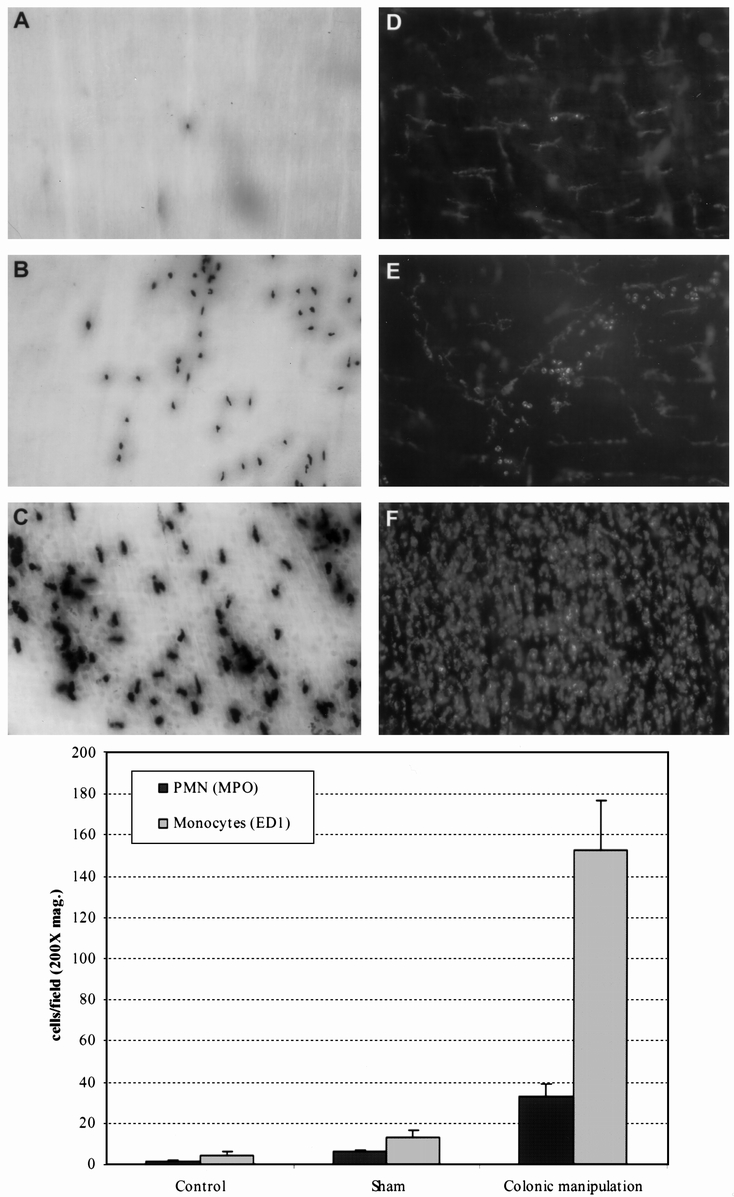

Leukocytic infiltrates within colonic muscularis whole mounts were investigated 24 hours after surgery. We focused on polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMN) and monocytes because they both possess the ability to release kinetically active substances that directly modulate smooth muscle function and are known to extravasate into the intestinal muscularis after surgical trauma. 6,11,20 As illustrated in Figure 5 A, myeloperoxidase-positive cells were found only occasionally in control specimens. In contrast, colonic manipulation resulted in a significant extravasation of neutrophils into the colonic muscularis (see Figs. 5B and 5C). Whole mounts from sham-operated animals showed only a few ED1-positive monocytes embedded in the resident macrophage network (see Figs. 5D and 5E). As shown in Figure 5F, colonic manipulation resulted in a massive and very dense monocytic infiltration. The extent of leukocyte recruitment in the colonic muscularis increased with the degree of the surgical trauma. Sham operation alone was sufficient to induce a small but significant increase in infiltrating monocytes (3.3-fold) and PMNs (4.3-fold) compared to controls (see Fig. 5, lower panel). This cellular inflammatory response was greatly enhanced in colonic muscularis whole mounts from manipulated animals (monocytes, 37.5-fold; PMNs, 23.8-fold vs. controls).

Figure 5. (Upper panel) Myeloperoxidase (MPO) staining and ED1-immunohistochemistry of colonic muscularis whole mounts showing leukocyte recruitment after colonic manipulation. (A) Occasionally a few MPO-positive cells were observed within a control muscularis whole mount. (B) Infiltrating MPO-positive cells 24 hours after colonic manipulation. (C) In addition to darkly stained polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs), numerous monocytes with a much lighter staining pattern were observed. (D, E) Presence of resident macrophages with a stellate appearance and only a few round monocytes after sham operation. (F) Massive monocytic infiltration after colonic manipulation. (Original magnification: 100× for A, B and 200× for C, D, E, F). (Lower panel) Histogram showing a significant increase in the number of infiltrating PMNs and monocytes after colonic manipulation compared with controls and shams. Leukocytes were counted at a magnification of 200×. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean.

Molecular Inflammatory Events After Colonic Manipulation

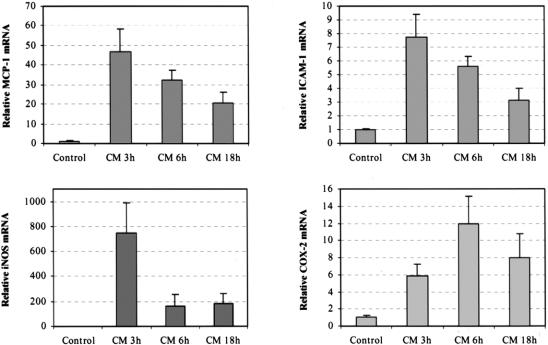

To determine the upregulation of inflammatory mediators, we performed quantitative real-time RT-PCR. Inflammatory gene mRNAs were measured in a time-course study comparing control and manipulated isolated colonic muscularis extracts. The chemokine MCP-1 and the leukocytic adhesion molecule ICAM-1 were measured because we have shown that they play a significant role in leukocyte recruitment within the intestinal muscularis. 10,21 As illustrated in Figure 6, samples from manipulated animals entered the exponential amplification phase earlier than those of the controls, which showed a higher template concentration. Figure 7 shows the results of the relative quantification using the comparative CT method. ICAM-1 and MCP-1 showed a distinct mRNA induction (ICAM-1, 7.8-fold; MCP-1, 46.5-fold), which peaked 3 hours after colonic manipulation. Both mediators declined slowly over time (6 hours: ICAM-1, 5.6-fold; MCP-1, 32.1-fold) but remained significantly elevated even 18 hours after manipulation.

Figure 6. Real-time reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction amplification plots of inflammatory mediators in the colonic muscularis after surgical manipulation. Each mediator-specific amplification was normalized to an endogenous control (GAPDH, panel bottom right). ΔRn values are plotted vs. cycle number. Inflammatory mediator amplification in the manipulated large intestinal muscularis extracts started earlier than amplification in the controls, showing a higher cDNA starting quantity.

Figure 7. Real-time two-step reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction analysis of inflammatory mediator mRNA CT values 3, 6, and 18 hours after surgery. ICAM-1 and MCP-1 peaked 3 hours after manipulation but remained elevated past 18 hours. iNOS peaked early at 3 hours and then rapidly declined. COX-2 peaked at 6 hours and remained elevated past 18 hours.

We also quantified the temporal upregulation of iNOS and COX-2, which are synthases for the generation of the smooth muscle kinetic inhibitory substances nitric oxide and prostaglandins. iNOS was rapidly and transiently induced a significant 764.4-fold 3 hours after surgery (see Figs. 6 and 7), whereas COX-2 peaked later with an 11.9-fold increase 6 hours after surgery and remained increased through 18 hours.

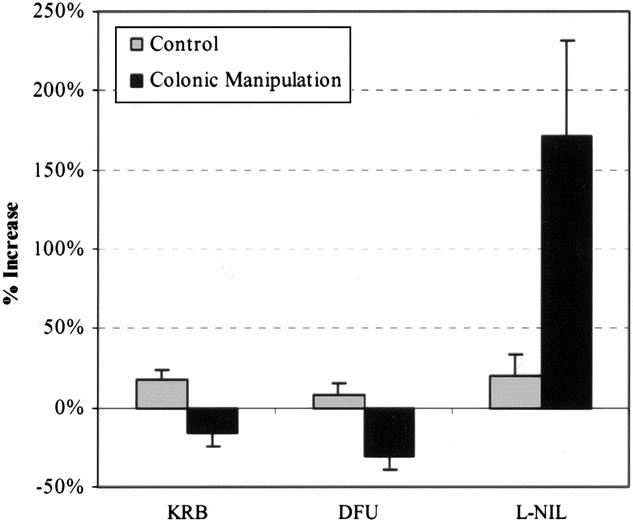

Pharmacologic Blockade of Kinetic Mediators Enhances Postoperative In Vitro Smooth Muscle Contractile Activity

As shown above, mRNA expression of the kinetically active mediators iNOS and COX-2 was enhanced after colonic manipulation. Therefore, we hypothesized that the local production of NO and eicosanoids caused by manipulation might play a role in the inhibition of colonic circular smooth muscle contractile activity. To test this hypothesis, we pharmacologically blocked iNOS and COX-2 activity in colonic smooth muscle strips taken from control and surgically manipulated animals. As shown in the traces in Figure 8 and plotted in the histogram in Figure 9, pretreatment with the selective iNOS inhibitor L-NIL (30 μmol/L) caused a significant 171% increase in spontaneous mechanical activity of circular smooth muscle strips from surgically manipulated animals, whereas the selective COX-2 inhibitor DFU (5mg/L) did not improve spontaneous activity. In control muscles, neither L-NIL nor DFU significantly changed spontaneous activity. After colonic manipulation, the response to bethanechol stimulation (1 μmol/L) was significantly less than in controls (55% decrease: 0.5 ± 0.12 vs. 0.94 ± 0.18 g/mm2/s). Similar to the effect on spontaneous activity of manipulated strips, L-NIL superfusion resulted in a significantly improved contractile response to bethanechol stimulation. In the presence of L-NIL, manipulated circular muscle contractions were improved to the level that the manipulated strip activity was not significantly different from controls (1.35 ± 0.24 g/mm2/s vs. 0.94 ± 0.18 g/mm2/s), whereas DFU had no significant effect on the bethanechol-stimulated manipulated muscle activity.

Figure 8. Representative in vitro spontaneous mechanical activity recorded from three adjacent colonic circular smooth muscle strips taken from one control animal (left column) and one surgical manipulated animal (right column). The spontaneous activity from the control animal did not significantly change in response to L-NIL or DFU. The manipulated muscle strip shows a marked increase in spontaneous activity in the presence of L-NIL (30 μmol/L; second row, right column), whereas DFU (5 mg/L, third row, right column) did not significantly improve the contractile activity (third row, right column).

Figure 9. Histogram showing effects of L-NIL (30 μmol/L) or DFU (5 mg/L) on spontaneous circular smooth muscle activity. No significant differences were found in spontaneous contractile activity between KRB-, L-NIL-, and DFU-perfused muscle strips from control animals. In contrast, L-NIL caused a 2.7-fold increase in the contractile activity of muscle strips from surgically manipulated animals. DFU had no significant effect on manipulated colonic circular smooth muscle.

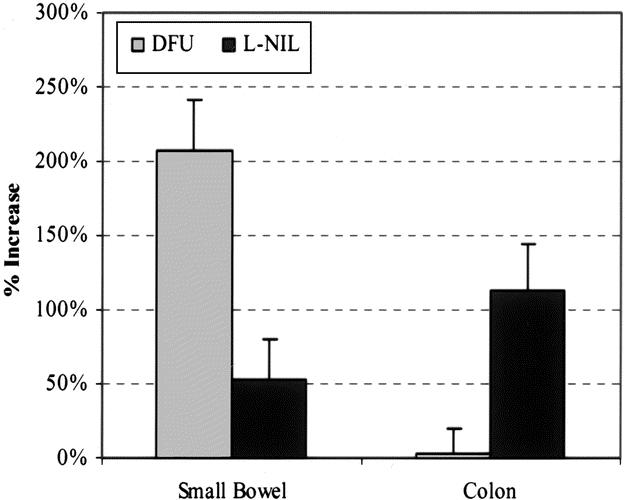

In contrast to the above result, we have previously shown that both DFU and L-NIL significantly improved postoperative small intestinal circular smooth muscle contractile activity. 11,12 However, the present results indicated that there are regional differences in mediator blockade. We directly investigated this regional difference in the effects of DFU (eicosanoids) and L-NIL (NO) by manipulating the entire intestine (small and large) and then determined the impact of COX-2 and iNOS blockade on colonic and small intestinal smooth muscle contractile activity in parallel experiments from the same animal. As depicted in Figure 10, perfusion with DFU (5 mg/L) caused a significant 206% improvement in small intestinal circular smooth muscle contractile activity but had no significant effect on colonic smooth muscle function. However, perfusion with the selective iNOS inhibitor L-NIL (30 μmol/L) significantly improved both small intestinal as well as colonic circular smooth muscle contractile activity (53% and 113%, respectively).

Figure 10. Histogram showing regional differences of L-NIL (30 μmol/L) or DFU (5 mg/L) on postoperative spontaneous circular smooth muscle contractile activity recorded after combined intestinal and colonic manipulation. DFU perfusion significantly improved contractile activity of the small intestinal muscularis but had no significant effect on colonic muscle strips. In contrast, L-NIL perfusion significantly improved both colonic and small intestinal smooth muscle contractile activity.

DISCUSSION

Intraabdominal surgery causes a transient disturbance in gastrointestinal motility and transit. Recently, the initiation of an inflammatory cascade as a consequence of surgical handling of the intestine has been proposed, and potential mediators as targets for therapeutic intervention have been identified. 11 However, the small bowel may be clinically less affected by postoperative ileus than other gastrointestinal organs, and arguably the restoration of colonic motility may be the rate-limiting step for postoperative recovery of the entire gastrointestinal tract. 2,3 Our study shows for the first time that light surgical trauma to the colon initiates a massive inflammatory response within the colonic muscularis that is directly associated with postoperative smooth muscle dysfunction. However, similar to our results on the small intestine, important molecular regional differences do appear to exist.

We developed a model of colonic manipulation similar to our previously described small intestinal ileus model. 5 The procedure mimics commonly performed operations with surgical handling of the large intestine. Commensurate with our recent observations in the small intestine, colonic manipulation caused a significant leukocyte infiltration into the muscularis at 24 hours. The massive postoperative extravasation of leukocytes into the colonic muscularis portends a preceding local molecular inflammatory response, which initiates leukocyte recruitment. It has previously been shown that the initiation of leukocyte recruitment in the small intestinal muscularis after manipulation or hemorrhagic shock is mediated through the expression of adhesion molecules, such as ICAM-1. 10,22 In addition, we recently showed that lipopolysaccharide induces monocyte extravasation in the small intestinal muscularis through the expression of macrophage-derived MCP-1. 21 Quantification of the postoperative mRNA expression for both mediators revealed a distinct upregulation, thus providing evidence for the importance of both ICAM-1 and MCP-1 as important mediators controlling the targeted transmigration of immunocompetent cells into the intestinal muscularis after surgical manipulation.

We have put forth the hypothesis that the molecular and cellular inflammatory milieu within the intestinal muscularis is a primary causative factor for prolonged postoperative intestinal ileus. To directly measure postsurgical colonic motility, we performed intracolonic pressure recordings 24 hours after surgery. These in vivo recordings showed a distinct impairment of colonic motility after surgical manipulation compared with controls and sham operations. A significant portion of this suppression in motility was caused by the direct modulation of the colonic muscularis, because in vitro spontaneous and bethanechol-stimulated muscle strip contractions were also significantly inhibited 24 hours after manipulation.

Interestingly, after selective colonic manipulation we also observed a decrease in transit of the nonabsorbable fluorescent marker FITC-dextran through the small intestine, which was not surgically manipulated. The observed small intestinal transit delay after colonic manipulation can be interpreted either as a result of colonic dysmotility, because the “in series” colon could act as a downstream barrier to small bowel transit, or as an impairment of small intestinal function itself. The concept of a nonlocalized or panintestinal effect of a site-specific local inflammatory response within the gut has already been hypothesized in response to data using parasitic infections of the gut. 23

The paradigm of the present study and our previous work is that inflammatory events within the muscularis externa, caused by intestinal handling, directly modulate smooth muscle contractile activity and subsequently changes in transit. 5,6,8,24 Similar to our reported observations in the small intestine, the data from the present study confirm an association between surgical trauma, leukocyte infiltration, and smooth muscle dysfunction within the colonic muscularis. Based on this and our previous work, we propose that activated resident as well as recruited leukocytes release kinetically active mediators that directly modulate motility. Leukocytes are potent secretors of kinetically active substances (eg, reactive oxygen intermediates, NO, and prostaglandins) that are capable of inhibiting smooth muscle contractile activity. 25–27 Although neuronal NO is known to be the principal inhibitory neuromuscular transmitter of the enteric nervous system, 25,28,29 insults to the gut such as abdominal surgery or lipopolysaccharide have recently been associated with NO generated from macrophage-derived iNOS. 11,20 In the present study, iNOS mRNA levels were massively elevated 3 hours after colonic manipulation. We have recently shown that intestinal manipulation transiently opens the intestinal barrier through which particles up to 0.8 μm transfer from the colonic lumen to the systemic circulation via the lymphatic system. 30 Thus, because the colon contains a large population of bacterial organisms, the escape of bacterial products could participate in the upregulation of iNOS within the muscularis after surgical insult. In addition, the relatively early increase in iNOS would suggest that it is coming primarily from normally resident cells within the intestinal muscularis. Our previous immunohistochemical studies would suggest that the muscularis macrophage network is a prime source for the generation of nitric oxide. 20

Functionally, the observed postoperative upregulation of iNOS within the muscularis and nitric oxide’s known potent inhibitory role on smooth muscle suggest it could participate in the development of postoperative colonic smooth muscle dysfunction. Thus, we investigated the functional role of NO within the intestinal muscularis by pharmacologic in vitro blockade of iNOS. L-NIL perfusion of colonic muscularis strips after surgical manipulation significantly ameliorated spontaneous and bethanechol-stimulated circular smooth muscle contractile activity almost to levels comparable to control activity. These data provide further evidence for the functional role of muscularis iNOS in the development of rodent postoperative colonic dysmotility.

The molecular data also indicated that the inducible inflammatory mediator COX-2 might participate in the development of postoperative colonic muscularis dysfunction. Eicosanoids are catalytic products of COX-2 and are known modulators of gastrointestinal smooth muscle function. 27 Further, COX-2 has been associated with postoperative intestinal dysmotility, 31 and selective COX-2 inhibition with DFU has been shown to significantly ameliorate small intestinal smooth muscle dysfunction in a rodent model of postoperative ileus. 12 In the present study, we detected a significant increase in COX-2 mRNA expression within the colonic muscularis. However, unlike our previous observations in the small intestine, acute perfusion with the selective COX-2 inhibitor DFU did not alter spontaneous or bethanechol-stimulated circular colonic muscularis contractility. These results suggested a regional difference in the functional role of COX-2 in the operated colon versus the small intestine. We investigated this phenomenon further by performing in vitro experiments on the small intestine and colon using DFU on muscle strips obtained from the same animal, which had received a combined intestinal and colonic manipulation. These results confirmed a major role for postoperative COX-2 expression in inhibiting jejunal smooth muscle function. However, these results also showed that acute COX-2 inhibition with DFU had no significant effects on midcolonic circular smooth muscle function. Eicosanoids have been shown to have differential effects on longitudinal and circular smooth muscle 32–35 and, further, to have regional effects on the colon. 35,36 The regional generation of the numerous eicosanoid end-products may need to be investigated to shed light on this aspect of ileus.

In conclusion, the data presented above provide evidence that the colonic muscularis itself is an immunologically active organ that significantly participates in the genesis of immune responses after surgical insult through the generation of chemokines and the upregulation of adhesion molecules. The results also show that postoperative intestinal dysmotility is caused by inflammatory events, in which iNOS plays a key role in directly inhibiting colonic circular smooth muscle motor function. Further, regional differences in the direct functional effects of COX-2-generated eicosanoids are clearly evident within the small and large intestines.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sandra Tögel, Muhannad Kanbour, and Bryan S. Thompson for their technical help.

Footnotes

Correspondence: Anthony J. Bauer, PhD, Department of Medicine/Gastroenterology, University of Pittsburgh, S849 Scaife Hall, 3550 Terrace Street, Pittsburgh, PA 15261.

E-mail: tbauer+@pitt.edu

Supported by National Institute of Health grants R01-GM-58241, P50-GM-53789, and DK02488 and a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (TU 116/2-1).

Accepted for publication November 2, 2001.

References

- 1.Prasad M, Matthews JB. Deflating postoperative ileus. Gastroenterology 1999; 117: 489–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holte K, Kehlet H. Postoperative ileus: a preventable event. Br J Surg 2000; 87: 1480–1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graber JN, Schulte WJ, Condon RE, et al. Relationship of duration of postoperative ileus to extent and site of operative dissection. Surgery 1982; 92: 87–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tache Y, Monnikes H, Bonaz B, et al. Role of CRF in stress-related alterations of gastric and colonic motor function. Ann NY Acad Sci 1993; 697: 233–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalff JC, Schraut WH, Simmons RL, et al. Surgical manipulation of the gut elicits an intestinal muscularis inflammatory response resulting in postsurgical ileus. Ann Surg 1998; 228: 652–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalff JC, Buchholz BM, Eskandari MK, et al. Biphasic response to gut manipulation and temporal correlation of cellular infiltrates and muscle dysfunction in rat. Surgery 1999; 126: 498–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roberts JP, Benson MJ, Rogers J, et al. Characterization of distal colonic motility in early postoperative period and effect of colonic anastomosis. Dig Dis Sci 1994; 39: 1961–1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eskandari MK, Kalff JC, Billiar TR, et al. Lipopolysaccharide activates the muscularis macrophage network and suppresses circular smooth muscle activity. Am J Physiol 1997; 273: G727–G734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalff JC, Schwarz NT, Walgenbach KJ, et al. Leukocytes of the intestinal muscularis: their phenotype and isolation. J Leukoc Biol 1998; 63: 683–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalff JC, Carlos TM, Schraut WH, et al. Surgically induced leukocytic infiltrates within the rat intestinal muscularis mediate postoperative ileus. Gastroenterology 1999; 117: 378–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalff JC, Schraut WH, Billiar TR, et al. Role of inducible nitric oxide synthase in postoperative intestinal smooth muscle dysfunction in rodents. Gastroenterology 2000; 118: 316–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwarz NT, Kalff JC, Billiar TR, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 mediates a significant component of postoperative ileus. Gastroenterology 1999; 116: 1080. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kosuga K, Yui Y, Hattori R, et al. Cloning of an inducible nitric oxide synthase from rat polymorphonuclear cells. Endothelium 1994; 2: 217–221. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu K, Robida AM, Murphy TJ. Immediate-early MEK-1-dependent stabilization of rat smooth muscle cell cyclooxygenase-2 mRNA by G-alpha(q)-coupled receptor signaling. J Biol Chem 2000; 275: 23012–23019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kita Y, Takashi T, Iigo Y, et al. Sequence and expression of rat ICAM-1. Biochim Biophys Acta 1992; 1131: 108–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoshimura T, Takeya M, Takahashi K. Molecular cloning of rat monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) and its expression in rat spleen cells and tumor cell lines. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1991; 174: 504–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tso JY, Sun XH, Kao TH, et al. Isolation and characterization of rat and human glyceraldehyde-3- phosphate dehydrogenase cDNAs: genomic complexity and molecular evolution of the gene. Nucleic Acids Res 1985; 13: 2485–2502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmittgen TD, Zakrajsek BA, Mills AG, et al. Quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction to study mRNA decay: comparison of endpoint and real-time methods. Anal Biochem 2000; 285: 194–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pezzone MA, Fraser MO, Van Bibber MM, et al. Physiologic evaluation of colonic motility in awake c-kit-deficient mice and immunofluorescence evaluation of colonic interstitial cells of cajal. In: Krammer HJ, Singer MV, eds. Neurogastroenterology: from the basics to the clinics. London: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2000: 461–469.

- 20.Eskandari MK, Kalff JC, Billiar TR, et al. LPS-induced muscularis macrophage nitric oxide suppresses rat jejunal circular muscle activity. Am J Physiol 1999; 277: G478–G486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Türler A, Schwarz NT, Türler E, et al. MCP-1 causes leukocyte recruitment and subsequently endotoxemic ileus in rat. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2002; 282 (1): G145–G155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalff JC, Hierholzer C, Tsukada K, et al. Hemorrhagic shock results in intestinal muscularis intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM-1) expression, neutrophil infiltration, and smooth muscle dysfunction. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 1999; 119: 89–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marzio L, Blennerhassett P, Chiverton S, et al. Altered smooth muscle function in worm-free gut regions of Trichinella-infected rats. Am J Physiol 1990; 259: G306–G313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hierholzer C, Kalff JC, Audolfsson G, et al. Molecular and functional contractile sequelae of rat intestinal ischemia/reperfusion injury. Transplantation 1999; 68: 1244–1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stark ME, Bauer AJ, Sarr MG, et al. Nitric oxide mediates inhibitory nerve input in human and canine jejunum. Gastroenterology 1993; 104: 398–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nathan CF. Secretory products of macrophages. J Clin Invest 1987; 79: 319–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eberhart CE, Dubois RN. Eicosanoids and the gastrointestinal tract. Gastroenterology 1995; 109: 285–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salzman AL. Nitric oxide in the gut. New Horiz 1995; 3: 352–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Christinck F, Jury J, Cayabyab F, et al. Nitric oxide may be the final mediator of nonadrenergic, noncholinergic inhibitory junction potentials in the gut. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 1991; 69: 1448–1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwarz NT, Beer-Stolz D, Simmons RL, et al. Pathogenesis of paralytic ileus: intestinal manipulation opens a transient pathway between the intestinal lumen and the leukocytic infiltrate of the jejunal muscularis. Ann Surg (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Josephs MD, Cheng G, Ksontini R, et al. Products of cyclooxygenase-2 catalysis regulate postoperative bowel motility. J Surg Res 1999; 86: 50–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hunt RH, Dilawari JB, Misiewicz JJ. The effect of intravenous prostaglandin F2 alpha and E2 on the motility of the sigmoid colon. Gut 1975; 16: 47–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pairet M, Bouyssou T, Ruckebusch Y. Colonic formation of soft feces in rabbits: a role for endogenous prostaglandins. Am J Physiol 1986; 250: G302–G308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Staumont G, Fioramonti J, Frexinos J, et al. Changes in colonic motility induced by sennosides in dogs: evidence of a prostaglandin mediation. Gut 1988; 29: 1180–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burakoff R, Percy WH. Studies in vivo and in vitro on effects of PGE2 on colonic motility in rabbits. Am J Physiol 1992; 262: G23–G29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Diener M, Gabato D. Thromboxane-like actions of prostaglandin D2 on the contractility of the rat colon in vitro. Acta Physiol Scand 1994; 150: 95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]