Abstract

Objective

To assess the feasibility and safety of duct-to-duct biliary anastomosis for living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) utilizing the right lobe.

Summary Background Data

Biliary tract complications remain one of the most serious problems after liver transplantation. Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy has been a standard procedure for biliary reconstruction in LDLT with a partial hepatic graft. However, end-to-end choledochocholedochostomy is the technique of choice for biliary reconstruction and yields a more physiologic bilioenteric continuity than can be achieved with Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy. The authors performed right lobe LDLT with end-to-end duct-to-duct biliary anastomosis, and this study assessed retrospectively the relation between the manner of reconstruction and complications.

Methods

Between July 1999 and December 2000, 51 patients (11–67 years of age) underwent 52 right lobe LDLTs with duct-to-duct biliary reconstruction and remained alive more than 1 month after their transplantation. Interrupted biliary anastomosis was performed for 24 transplants and the continuous procedure was used for 28. A biliary tube was inserted downward into the common bile ducts through the recipient’s cystic duct in 16 transplants (cystic drainage), or a biliary stent tube was pushed upward into the anastomosis through the cystic duct in four transplants (cystic stent), or upward into the anastomosis through the wall of the common bile duct in 31 transplants (external stent).

Results

Biliary anastomotic procedures consisted of 34 single end-to-end anastomoses, 11 double end-to-end anastomoses, and 7 single anastomoses for double hepatic ducts. Overall, 5 patients developed leakage (9.6%) and 12 patients suffered stricture (23.0%). For biliary anastomosis with interrupted suture, the incidence of stricture was significantly higher in the cystic drainage group (53.3%, 8/15) than in the stent group consisting of cystic stent and external stent (0%, 0/8). While the respective incidences of leakage and stricture were 20% and 53.3% for intermittent suture with a cystic drainage tube (n = 15), they were 7.7% and 15.4% for a continuous suture with an external stent (n = 26). There was a significant difference in the incidence of stricture.

Conclusions

Duct-to-duct reconstruction with continuous suture combined with an external stent represents a useful technique for LDLT utilizing the right lobe, but biliary complications remain significant.

With various refinements in surgical techniques, organ preservation, and immunosuppressive management, complications following liver transplantation have been reduced. Biliary complications, however, still occur frequently after liver transplantation (7–29%) and have retained a high risk of significant mortality and morbidity. 1–3 Technical problems have been the major reasons for biliary complications, and various innovations for biliary reconstruction have been achieved for cadaveric liver transplantation. 4–8

For living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) using partial liver grafts, Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy (RYHJ) has been a standard technique for biliary reconstruction because the majority of LDLT recipients have been patients with biliary atresia. 9,10 Recent reports on biliary complications still show an incidence of 12% to 28% after RYHJ in LDLT. 1,11 For LDLT using right lobe grafts, RYHJ has been used as the standard procedure. 12,13

Although RYHJ has been the standard procedure in LDLT as well as in general surgery, 14 the disadvantages of this technique are a comparatively long operative time and higher risk of contamination due to construction of the Roux-en-Y limb. Moreover, the re-established bilioenteric continuity is not physiologic. In contrast, duct-to-duct reconstruction is the standard technique of choice for biliary anastomosis in cadaveric liver transplantation. 15 When the duct-to-duct technique can be used for LDLT, an extraintestinal anastomosis can be avoided, the continuity is more physiologic than that of RYHJ, and preservation of the sphincter function of the lower bile duct may reduce the risk of enteric reflux into the biliary tract. 16

This report describes our surgical trials regarding end-to-end duct-to-duct biliary reconstruction for LDLT, focuses on technical considerations regarding the preservation of blood supply for biliary systems, and assesses the effects of suture mode and stent tube on biliary complications during long-term follow-up.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Between July 1999 and December 2000, 51 patients (11–67 years old, 28 male patients and 23 female patients) underwent 52 right lobe LDLTs with duct-to-duct biliary reconstruction at Kyoto University Hospital and survived longer than 1 month after their transplantation. The body weight of the recipients ranged from 35 to 89 kg. Primary transplants were performed for 50 patients and retransplants for 2. The underlying diseases were liver cirrhosis (n = 16), Budd-Chiari disease (n = 1), metabolic liver diseases (n = 3), primary biliary cirrhosis (n = 6), primary sclerosing cholangitis (n = 1), fulminant hepatic failure (n = 11), hepatocellular carcinoma (n = 12), and retransplantation (n = 2).

Donor Operation

Standard surgical techniques for LDLT have been previously described. 9,13 An intraoperative cholangiogram was routinely performed before parenchymal transection to determine the anatomy of the bile ducts and to decide the correct point for bile duct transection. Minimal dissection of pericholedochal tissue was required at this point, and the hepatic ducts were separated with scissors. The anterior wall of the right hepatic duct is covered with hilar parenchymal tissue. Since this often makes it difficult to identify the proximal area of the right hepatic ducts from the surface at the front, we dissected the connective tissue between the right hepatic duct and right hepatic artery. After identification of the posterior wall of the right hepatic duct and the anatomy of the bifurcation, the right hepatic duct was cut 2 or 3 mm away from the bifurcation.

The isolated grafts were stored at 4°C in either University of Wisconsin or HTK solution. 17 The ends of the remnant hepatic ducts were closed with a continuous suture using 6-0 polydioxanone absorbable monofilament, and a cholangiogram was performed to ensure there was no leakage or stricture.

Recipient Operation

Patients who had liver diseases without the extrahepatic biliary tract being affected were candidates for this procedure. Hilar dissection was performed carefully to preserve an adequate blood supply for the native bile duct. Furthermore, to preserve the “3 o’clock” and “9 o’clock” vessels and the retroportal artery of the recipient’s common bile duct, dissection around the common bile duct had to be restricted. 18–20 After cholecystectomy, the bile duct was ligated and divided above the hilar bifurcation.

Biliary anastomosis was performed after vascular anastomosis. To ensure an adequate blood supply for the former, the ends of both the recipient’s and donor’s ducts were debrided, because significant arterial bleeding from the cut ends is a good sign; without such bleeding, the bile duct needs to be shortened. 16

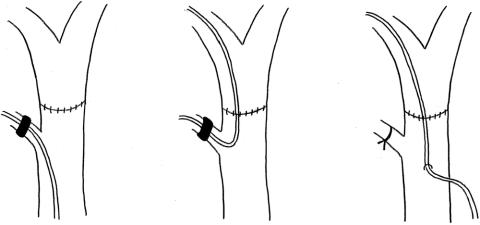

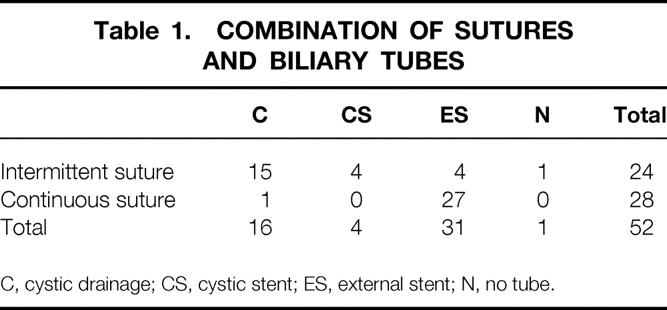

The graft hepatic duct was anastomosed in an end-to-end fashion to the recipient bile duct. When bile ducts in a graft were far apart, they were anastomosed separately. The anastomosis was begun at the posterior wall with interrupted or continuous 6-0 PDS sutures, after which the anterior wall of the anastomosis was completed. 16 For cystic drainage, a 4 French polyethylene tube was then inserted through the remaining cystic duct and pushed downward into the recipient common bile duct. For the first 4 patients, this tube was placed through the anastomosis as a splint (cystic stent;Fig. 1), but in the other 16 cases, the tube was pushed down into the common bile duct only to reduce the pressure of the biliary tract (cystic drainage). 16,21 The tube was attached to the end of the cystic duct with a 6-0 prolene suture and kept in place in the cystic duct with a rubber-band hemorrhoid ligator. For an external stent, the tube was placed through the anastomosis as a splint and was pulled out through the common bile duct above the duodenum routinely. The tube was then anchored to the anastomosis with an absorbable stitch. We changed the procedure for biliary reconstruction from cystic drainage to external stent in May 2000 and from interrupted to continuous suturing in July 2000. The number of transplantations with various combinations of sutures and biliary tubes is shown in Table 1.

Figure 1. Cystic drainage (left), cystic stent (middle), and external stent (right). For cystic drainage, a 4 French tube was inserted through the remnant cystic duct and placed into the common bile duct. For external stent, the tube was placed through the anastomosis as a splint and was pulled out through the common bile duct above the duodenum. The tube was anchored to the anastomosis with an absorbable stitch.

Table 1. COMBINATION OF SUTURES AND BILIARY TUBES

C, cystic drainage; CS, cystic stent; ES, external stent; N, no tube.

The postoperative care and our immunosuppression regimen have been described previously. 9,13 Biliary complications were diagnosed clinically and radiologically, and for the patients furnished with the tube, a postoperative cholangiogram was performed 1 to 2 weeks after transplantation, and the tube through the cystic duct was removed when there were no further problems. The external stent was removed 2 months after transplantation.

Whenever significant symptoms were observed, an emergency cholangiogram was performed. A biliary complication was defined as radiologic evidence of leakage or stricture. The follow-up period ranged from 6 to 23 months for surviving patients.

RESULTS

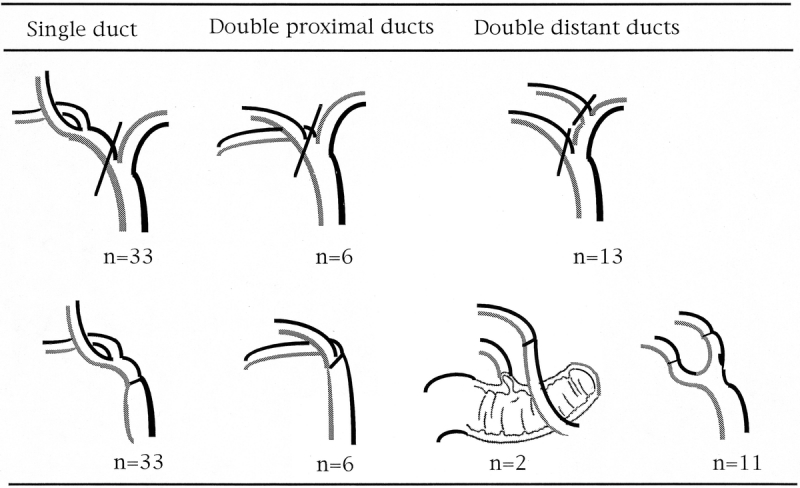

The operative cholangiogram showed variations in biliary branching patterns (Fig. 2). For 33 recipients with a single bile duct of the graft, end-to-end duct-to-duct biliary anastomosis was performed, while 19 grafts had double bile ducts (36.5%). In 11 cases with two bile ducts, each orifice was anastomosed separately to the right and left hepatic ducts or the common hepatic duct and the cystic duct of the recipients. In six cases with proximal double orifices, the septum between the double orifices was incised to create a common bile duct orifice, and after trimming of this orifice, single duct-to-duct reconstruction was performed. In two other cases with two distant orifices, one orifice was anastomosed to the existing Roux-en-Y limb and the other to the common bile duct in an end-to-end fashion. Oral intake could be reinstituted on postoperative day 4 to 11, depending on the clinical condition.

Figure 2. Anatomy of the intrahepatic biliary system and schema of reconstruction for right lobe transplantation.

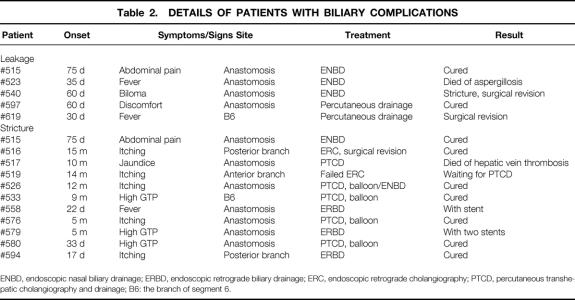

The follow-up period ranged from 6 to 24 months for surviving patients. Sixteen patients developed biliary complications as shown in Table 2. Five patients developed major leakage, with the onset ranging from 35 to 75 days after transplantation. Leakage was found at the orifice of the branch of segment 6 in one patient and at the anastomosis in four patients. One patient was treated successfully with percutaneous drainage, two patients underwent successful surgical revision with the Roux-en-Y technique, and one patient was treated successfully by endoscopic nasal drainage. Twelve patients developed biliary stricture. The onset ranged from 17 days to 15 months after transplantation. The stricture was found at the orifice of the branch of segment 6 in one, of the anterior branch in one, of the posterior branch in two, and at the anastomosis in eight. Five patients were treated with percutaneous transhepatic drainage and balloon-plasty and five others with endoscopic intervention. Two patients required surgical revision with the Roux-en-Y technique. Ten of the 12 patients with stricture are alive and 8 of them are free from any stent or drainage. One patient in addition to these 16 showed bile leakage after removal of the external stent tube but was successfully treated with antibiotics.

Table 2. DETAILS OF PATIENTS WITH BILIARY COMPLICATIONS

ENBD, endoscopic nasal biliary drainage; ERBD, endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage; ERC, endoscopic retrograde cholangiography; PTCD, percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography and drainage; B6: the branch of segment 6.

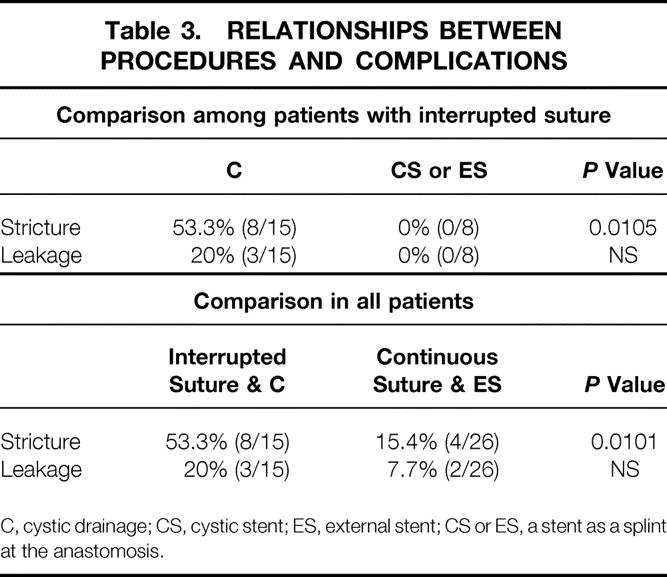

The effects of the manner of reconstruction (i.e., suture and biliary tube) on biliary complications was analyzed (Table 3). In biliary anastomosis with interrupted suture, the incidence of stricture was significantly higher for the cystic drainage group (8/15, 53.3%) than for the cystic stent and external stent group in which a stent was used as a splint at the anastomosis (0/8, 0%) (P = .0105). While the respective incidences of leakage and stricture were 20% and 53.3% for an intermittent suture with cystic drainage tube (n = 15), they were 7.7% and 15.4% for a continuous suture with external stent (n = 26). The difference in the incidence of stricture was significant (P = .0101). There was no significant difference among the procedures regarding the incidence of leakage. There was no significant correlation between or among hepatic artery complications, cytomegalovirus diseases, number of graft bile ducts, and biliary complications.

Table 3. RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN PROCEDURES AND COMPLICATIONS

C, cystic drainage; CS, cystic stent; ES, external stent; CS or ES, a stent as a splint at the anastomosis.

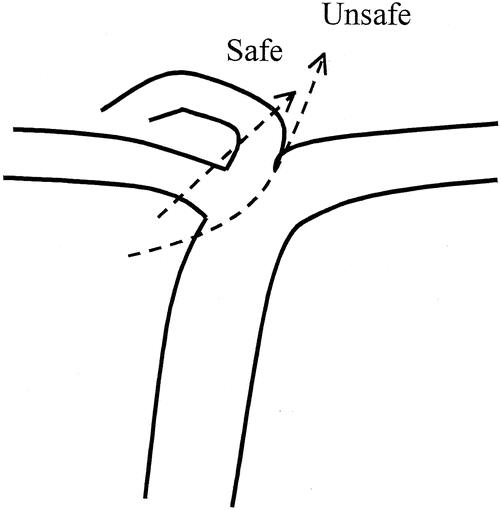

All donors are alive, but five developed biliary leakage and two biliary stricture requiring radiologic treatment intervention 4 months and 6 months after surgery. During this period, we used to cut deep into the left side of the right bile duct to obtain a single hole for the grafts because of proximal bifurcation. After this experience with donor complications, we leave 2 or 3 mm of the proximal right hepatic duct on the donor’s side to ensure complete closure, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Lines indicating safe and unsafe dissection for the right hepatic duct with proximal bifurcation.

DISCUSSION

The blood supply for the biliary anastomosis is a major concern in duct-to-duct biliary reconstruction. Biliary ischemia may lead to a posttransplant biliary complications known as the ischemic type. 22,23 The occurrence of ischemic-type biliary complications is associated with poor graft prognosis. 24 Recognition of the importance of an adequate blood supply is fundamental for technical improvements in biliary reconstruction. 18–20,25 The arterial blood supply of the biliary system has been described by several investigators. A fine arterial plexus covering the surface of the biliary tract is one of the important sources of this blood supply. Further, the vascular supply for both hepatic ducts depends on an arterial network that is bilaterally fed by the plexus from branches of both the right and left hepatic artery. During the donor operation, dissection along the bile duct should thus not be too close to the bile duct wall, so as not to endanger this fine arterial plexus. Because the bile duct blood supply from the graft side tends to be tenuous and the pathologic changes in the biliary tree are generally localized proximally to the anastomotic site, microcirculatory problems are of greater concern for the donor bile duct. Therefore, shortening of the donor duct segment results in an improved circulatory status around the biliary anastomosis, so that our technique is especially suitable for LDLT with a limited length of the graft hepatic duct.

For the recipient operation, the common hepatic duct for the anastomosis should have an adequate blood supply from the ascending axial vessels, so that dissection around the bile duct should be minimized and the plexus around the bile duct preserved as much as possible. 20 The “3 o’clock”, “9 o’clock,” and retroportal arteries give rise to multiple arteriolar branches, which form a free anastomosis within the wall of the bile duct. 20 Vellar found that the arterial plexus on the bile duct surface is usually supplied from below by the ascending marginal arteries from the posterior-superior pancreaticoduodenal artery, which is a branch of the gastroduodenal artery. 26 Moreover, the marginal arteries form an anastomosis within the mucosa of the bile duct and also contribute to the blood supply for the anastomosis. 20

In our series, the onset of leakage ranged from 1 to 2 months after transplant, which was later than for whole liver transplant. 27,28 The shortness of the graft bile duct contributing to good blood supply may well contribute to this delay in the onset of leakage. Four patients developed biliary stricture within 3 months, four between 3 months and 1 year and three 1 year after transplant. This timing was similar to the results of cadaveric liver transplantation reported by Davidson et al, 28 although Greif et al 27 mentioned that the onset of anastomosis stricture in their cadaveric series generally ranged 3 to 6 months. The early onset may be related to surgical technique and the late onset to fibrotic healing. 29

The optimal procedure for biliary reconstruction is an important surgical issue. In this study, we were able to demonstrate only that continuous suture combined with a stent as a splint seemed to have the lowest incidence of problems, because there were not enough cases to compare the different types of drainage in the interrupted suture group independently from the different types of drainage into the continuous suture group. Generally speaking, duct-to-duct anastomosis in an end-to-end fashion is the most common mode of biliary reconstruction for cadaveric liver transplantation using the whole liver. 30 However, no conclusion has been reached whether running or intermittent suture is better. We could not compare continuous and interrupted suturing in this study because we combined all but one of continuous sutures with an external stent. However, the continuous suture is quicker, easier, and less expensive than the interrupted one. The use of a T-tube is also a matter of debate. Scatton et al reported a lower incidence of overall biliary complication for the T-tube group. 31 However, the most frequent complication was leakage after T-tube removal, while the incidence of anastomotic stricture was greater for the non-T-tube group. Tung and Kimmey reported the same findings in their review. 30 Our anastomotic stricture rate was significantly lower for transplantation with a stent tube used as a splint at the anastomosis than with a cystic drainage tube, even though the tube diameter was small. Further, the incidence of leakage after removal of the tube was only 3% (1/31) for our external stent group but around 30% as reported for T-tube use. 30,31 In other words, a small external biliary stent could be used even for whole liver transplantation. Easy access for a cholangiogram is very useful for postoperative management. PTCD or ERCP is technically safe today but still constitutes a stress for patients. Hence, the continuous suture combined with an external stent is our procedure of choice.

Theoretically, patients with a primary disease affecting the extrahepatic bile duct system cannot undergo duct-to-duct anastomosis because development of malignancy at the common bile duct is a matter of concern. Even with an effort on frozen section to eliminate any risk for malignancy, high-grade dysplasia in the distal bile duct could not be easily determined on frozen section. However, Distante et al reported that duct-to-duct biliary reconstruction for PSC patients is satisfactory unless the distal common bile duct is strictured. 32 Goss et al also reported that Roux-en Y choledochojejunostomy was performed only if inflammation was noted at the common bile duct, and strict selection of patients for duct-to-duct reconstruction should produce satisfactory results. 33 We therefore basically apply duct-to-duct reconstruction for PSC unless there is any inflammation or common duct frozen-section biopsy specimen shows any suspicion of malignancy. The appropriateness of this strategy should be assessed in a long-term follow-up study.

Biliary drainage combined with restoration of the normal anatomy has been satisfactory, although long-term complications are still similar to those seen in cadaveric transplants. To obtain better results, further technical improvement will be needed.

Footnotes

Correspondence: Koichi Tanaka, MD, Department of Transplantation Immunology, Faculty of Medicine, Kyoto University, 54 Kawahara-cho, Shogoin, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto, Japan, 606-8507.

E-mail: koichi@kuhp.kyoto-u.ac.jp

Supported in part by a Research Grant for Immunology, Allergy and Organ Transplant from the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Japan.

Accepted for publication November 29, 2001.

References

- 1.Egawa H, Uemoto S, Inomata Y, et al. Biliary complications in pediatric living related liver transplantation. Surgery 1998; 124: 901–910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lopez RR, Benner KG, Ivancev K, et al. Management of biliary complications after liver transplantation. Am J Surg 1992; 163: 519–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sawyer RG, Punch JD. Incidence and management of biliary complications after 291 liver transplants following the introduction of transcystic stenting. Transplantation 1998; 66: 1201–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belli L, De Carlis L, Del Favero E, et al. Biliary complications in orthotopic liver transplantation: experience with a modified technique of duct-to-duct reconstruction. Transplant Int 1991; 4: 161–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anselmi M, Sherlock D, Buist L, et al. Gallbladder conduit vs end-to-end anastomosis of the common bile duct in orthotopic liver transplantation. Transplant Proc 1990; 22: 2295–2296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaib E, Friend PJ, Jamieson NV, et al. Biliary tract reconstruction: comparison of different techniques after 187 paediatric liver transplantations. Transplant Int 1994; 7: 39–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Carlis L, Rondinara GF, Arcidiacono R, et al. Modified duct-to-duct reconstruction after orthotopic liver transplantation: early and long-term results in 230 procedures. Transplant Proc 1994; 26: 3547–3549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neuhaus P, Blumhardt G, Bechstein WO, et al. Technique and results of biliary reconstruction using side-to-side choledochocholedochostomy in 300 orthotopic liver transplants. Ann Surg 1994; 219: 426–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanaka K, Uemoto S, Tokunaga Y, et al. Surgical techniques and innovations in living related liver transplantation. Ann Surg 1993; 217: 82–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fan ST, Lo CM, Liu CL. Technical refinement in adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation using right lobe graft. Ann 2000; 231: 126–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Egawa H, Kasahara M, Inomata Y, et al. Long-term outcome of living related liver transplantation for patients with intrapulmonary shunting and strategy for complications. Transplantation 1999; 67: 712–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marcos A, Fisher RA, Ham JM, et al. Right lobe living donor liver transplantation. Transplantation 1999; 68: 798–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inomata Y, Uemoto S, Asonuma K, et al. Right lobe graft in living donor liver transplantation. Transplantation 2000; 69: 258–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bismuth H, Castaing D, Gugenheim J, et al. Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy: a safe procedure for biliary anastomosis in liver transplantation. Transplant Proc 1987; 19: 2413–2415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nuno J, Vicente E, Turrion VS, et al. Biliary tract reconstruction after liver transplantation: with or without T-tube? Transplant Proc 1997; 29: 564–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rouch DA, Emond JC, Thistlethwaite JR Jr, et al. Choledochocholedochostomy without a T tube or internal stent in transplantation of the liver. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1990; 170: 239–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Erhard J, Lange R, Scherer R, et al. Comparison of histidine-tryptophan-ketoglutarate (HTK) solution versus University of Wisconsin (UW) solution for organ preservation in human liver transplantation. A prospective, randomized study. Transplant Int 1994; 7: 177–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stapleton GN, Hickman R, Terblanche J. Blood supply of the right and left hepatic ducts. Br J Surg 1998; 85: 202–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nery JR, Frasson E, Rilo HL, et al. Surgical anatomy and blood supply of the left biliary tree pertaining to partial liver grafts from living donors. Transplant Proc 1990; 22: 1492–1496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Northover JM, Terblanche J. A new look at the arterial supply of the bile duct in man and its surgical implications. Br J Surg 1979; 66: 379–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rolles K, Dawson K, Novell R, et al. Biliary anastomosis after liver transplantation does not benefit from T tube splintage. Transplantation 1994; 57: 402–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schlitt HJ, Meier PN, Nashan B, et al. Reconstructive surgery for ischemic-type lesions at the bile duct bifurcation after liver transplantation. Ann Surg 1999; 229: 137–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanchez-Urdazpal L, Gores GJ, Ward EM, et al. Clinical outcome of ischemic-type biliary complications after liver transplantation. Transplant Proc 1993; 25: 1107–1109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanchez-Urdazpal L, Gores GJ, Ward EM, et al. Diagnostic features and clinical outcome of ischemic-type biliary complications after liver transplantation. Hepatology 1993; 17: 605–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Colonna JOD, Shaked A, Gomes AS, et al. Biliary strictures complicating liver transplantation. Incidence, pathogenesis, management, and outcome. Ann Surg 1992; 216: 344–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vellar ID. The blood supply of the biliary ductal system and its relevance to vasculobiliary injuries following cholecystectomy. Aust NZ J Surg 1999; 69: 816–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greif F, Bronsther OL, Van Thiel DH, et al. The incidence, timing, and management of biliary tract complications after orthotopic liver transplantation. Ann Surg 1994; 219: 40–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davidson ER, Rai R, Kurzawinski TR, et al. Prospective randomized trial of end-to-end versus side-to-side biliary reconstruction after orthotopic liver transplantation. Br J Surg 1999; 86: 447–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Porayko MK, Kondo M, Steers JL. Liver transplantation: Late complications of the biliary tract and their management. Semin Liver Dis 1995; 15: 139–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tung BY, Kimmey MB. Biliary complications of orthotopic liver transplantation. Dig Dis 1999; 17: 133–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scatton OS, Meunier B, Cherqui D, et al. Randomized trial of choledochocholedochostomy with or without a T tube in orthotopic liver transplantation. Ann Surg 2001; 233: 432–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Distante V, Farouk M, Kurzawinski TR, et al. Duct-to-duct biliary reconstruction following liver transplantation for primary sclerosing cholangitis. Transplant Int 1996; 9: 126–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goss JA, Shackleton CR, Farmer DG, et al. Orthotopic liver transplantation for primary sclerosing cholangitis. Ann Surg 1997; 225: 472–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]