Abstract

Objective

To analyze a large cohort of patients with stage III colon cancer to determine whether subgroup stratification better defines outcome.

Summary Background Data

The Tumor (T), Node (N), Metastasis (M) system is based on depth of tumor invasion into the colonic wall, the number of regional lymph nodes involved, and distant metastasis. Traditionally, colon cancer has been designated as stage III based on nodal involvement regardless of the depth (T1–4) of tumor penetration. Treatment decisions have been based on nodal involvement with less emphasis on colonic wall penetration in stage III patients.

Methods

Patients (n = 50,042) with stage III colon cancer reported to the National Cancer Data Base from 1987 through 1993 were analyzed. Observed survival was calculated by actuarial life table methods for three new node-positive subgroups (IIIA: T1/2, N1; IIIB: T3/4, N1; IIIC: any T, N2). The Cox proportional hazards model was used to test the prognostic strength of selected covariates.

Results

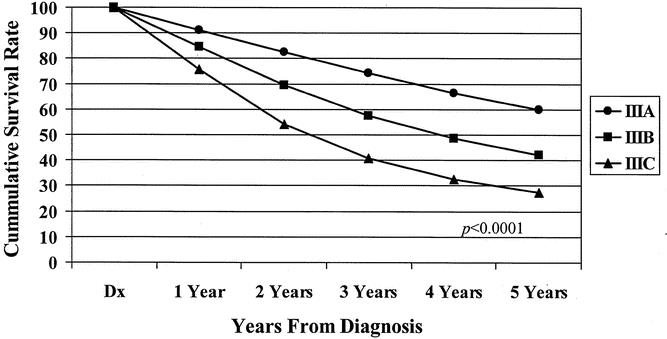

Three distinct subcategories within a traditional stage III cohort of colonic cancer were identified. Five-year observed survival rates for these three subcategories were 59.8%, IIIA; 42.0%, IIIB; and 27.3%, IIIC. Differences between subgroups were significant (P < .0001). Similar differences were calculated after stratification for treatment. A multivariate proportional hazards model identified the new stage III subgroups, modality of the first course of therapy, patient age, and tumor grade as significant independent prognostic covariates.

Conclusions

The current stage III designation of colon cancer excludes prognostic subgroups stratified for mural penetration (T1–4) or nodal involvement (N1 vs. N2). Analysis of a large data set supports stratification into three subsets, confirming the benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy in each subgroup. This strategy should be used in the reporting and staging of node-positive colon cancers.

Since 1987, 1 the International Union Against Cancer (UICC) and the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) have promoted a worldwide taxonomy of cancer staging (TNM) based on localized tumor characteristics (size or tumor penetration), nodal involvement (number or location), and the status of metastatic implants (presence or absence, target of metastasis). The group stage in the TNM system is based on a combination of locoregional tumor involvement and the presence of metastases.

The most recent strategies 2 of TNM staging of colon cancer have grouped patients having mesenteric nodal involvement into the stage III category despite variations in depth of tumor penetration of the colonic wall. Recent analysis of medium-sized patient data sets has suggested that stage III colon cancer is heterogeneous in survival patterns when differences in T and N categories are considered. 3 To determine the prognostic significance of subgroup stratification in staging patients with node-positive colon cancer, a large national outcomes tumor registry was used.

METHODS

The National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) is a hospital cancer registry-based, national clinical surveillance and outcomes database supported by the American College of Surgeons and the American Cancer Society. 4 The NCDB captures 70% to 75% of all newly diagnosed cancer cases in the United States annually. The data set contains slightly more than 477,000 cases of colon cancer reported for the years 1985 through 1993, of which 88,358 patients with stage III disease can be identified. From 1987 through 1993, a total of 50,042 surgically treated adult (>16 years of age) patients diagnosed with node-positive colon cancers were reported to the NCDB. Patients with clinical or pathologic evidence of metastasis were removed from analysis. A total of 1,705 hospitals (28% of acute care hospitals) reported cases during this time to the NCDB. Of this total, 576 (33.8%) were community or non-teaching hospitals, 515 (30.2%) were comprehensive community or minor-teaching hospitals, 325 (19.0%) were academic/research institutions, while the remaining 289 (17%) hospitals could not be classified into one of these three groups.

The cases included in this study constitute approximately 20% of node-positive (stage III) colon cancers diagnosed in the United States between 1987 and 1989 and approximately 37% of cases diagnosed between 1991 and 1993. This is consistent with previously reported increased hospital participation and reporting patterns to the NCDB. 5,6 Cases included in this study were reported as having been staged according to either the third 7 or fourth 8 editions of the AJCC’s Manual for Staging of Cancer. These prior editions included an N3 designation under the stage III group. This designation included nodal involvement in any lymph nodes along named vessels or to the highest apical node marked by the surgeon. In the currently used fifth edition, 2 the N3 designation was incorporated into the N1 or N2 categories indicating the number of nodes harboring tumor.

Survival rates were calculated using a proposed strategy dividing traditional stage III patients into three new subgroups: IIIA (T1/2, N1, M0), IIIB (T3/4, N1, M0), and IIIC (any T, N2, M0). Demographic characteristics including tumor location, patient age, gender, and ethnicity; in addition, the survival benefits of surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy were assessed.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics, including means and standard deviations, or counts and percentages were calculated. Observed survival rates (deaths from all causes) were calculated by standard actuarial life table methods, compounding survival in 1-month intervals from the date of diagnosis, with death from any cause as the endpoint. 9 Kaplan-Meier survival calculations and corresponding log-rank tests were performed to show differences in survival rates. Precise cause of death information is poorly reported from hospital cancer registry sources, therefore limiting computation of adjusted survival rates. A Cox proportional hazards regression model was fitted to test for prognostic contribution of covariates beyond those illustrated through stratified univariate survival calculations. 10,11 The primary endpoint was time of death, measured from the date of first diagnosis. The Cox model accounts for unequal duration of follow-up and censoring of living patients. The SPSS software (SPSS for Windows, Advanced Statistics, release 9.0, SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, 1999) was used for all analyses. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 50,042 patients were included in this analysis. The total group comprised 23,615 men (47.2%) and 26,427 women (52.8%). The average age of all patients was 69.9 years. White patients constituted 75% of the identified cases, African Americans 8.8%, Asian Americans 2.7%, patients of Hispanic origin 2.6%, while patients of unknown or unspecified ethnic background made up 11% of cases. The anatomical location of the primary tumor within the colon was specified for 97.4% of cases (n = 48,731). Patients with tumors in the right colon (cecum, ascending colon, and hepatic flexure) accounted for 47.8% (n = 23,278) of all cases. Tumors of the transverse colon occurred in 4,491 (9.2%) patients, and 43.0% (n = 20,962) had tumors located in the left colon (splenic flexure, descending, and sigmoid colon).

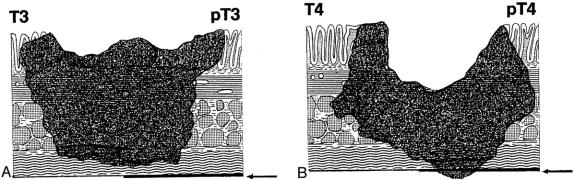

Three distinct subcategories within the traditional TNM stage III group are identified using the stage group definitions proposed in the sixth edition of the AJCC’s Cancer Staging Manual12 and based on analysis of survival data. The IIIA subgroup (n = 5,398) represents patients with T1/2 colonic wall involvement (invasion of submucosa or muscularis propria) (Fig. 1) and N1 nodal involvement (1–3 positive regional nodes). This subgroup represents 10.7% of all patients with stage III disease reported. The IIIB subgroup (n = 30,268) includes patients with T3/4 transmural involvement (invasion through muscularis propria and subserosa or the contiguous involvement of adjacent structures) (Fig. 2) and N1 regional nodal involvement. The IIIB group represents 60.5% of the stage III cohort. The IIIC subgroup (n = 14,376) is classified as any degree of mural involvement (T1–4) with four or more regional nodes positive (N2). This subgroup represents 28.8% of the stage III group.

Figure 1. Extent of T1 and T2 tumors. (Adapted from Hermanek P, Hutter R, Sobin L, et al. TNM Atlas, 4th ed. Berlin: Springer Publishers, 1997)

Figure 2. Extent of T3 and T4 tumors. (Adapted from Hermanek P, Hutter R, Sobin L, et al. TNM Atlas, 4th ed. Berlin: Springer Publishers, 1997)

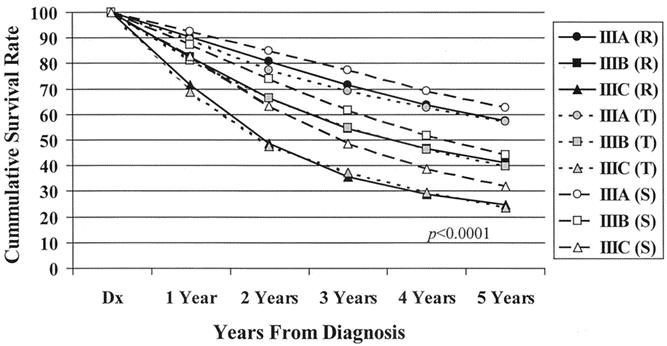

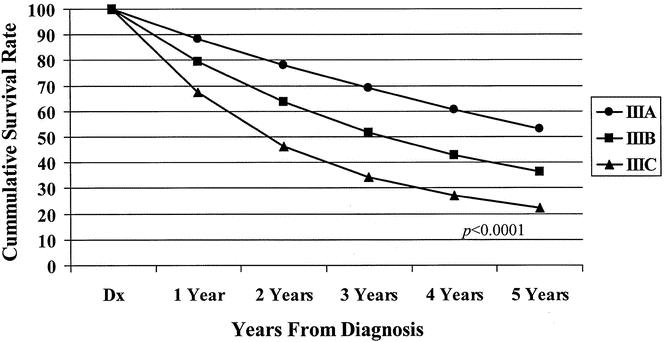

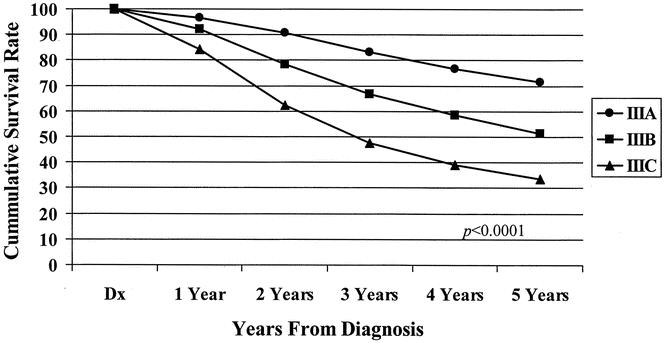

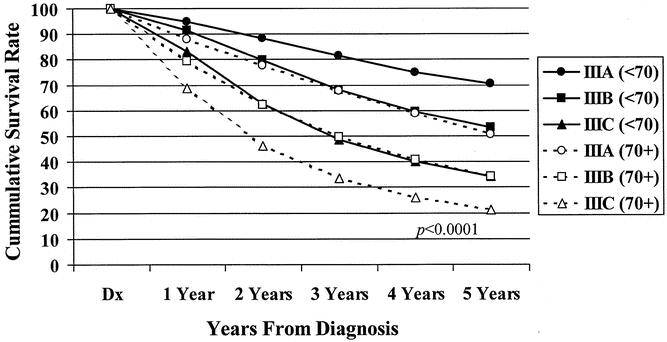

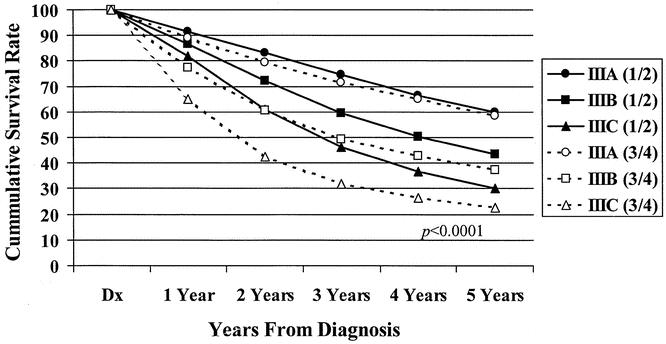

The 5-year observed survival rate for stage IIIA (T1/2, N1) patients was 59.8%. Patients with stage IIIB (T3/4, N1) disease had an observed survival rate of 42%, and the stage IIIC (any T, N2) group fared worse, with a 27.3% observed survival rate. The differences in the survival rates were statistically significant (P < .0001) among the three subgroups (Fig. 3). Analysis of the observed survival between T3N1 and T4N1 tumors showed a survival benefit of 16% for the former group. Because of the relatively small number of T4N1 tumors in the database, however, this difference did not reach statistical significance and did not warrant a separate stratification for the T4N1 group. Significant differences in survival rates were noted when the new stage III subgroups were stratified for colonic location (Fig. 4). When each newly designated stage III subgroup is stratified by other factors, the overall differences in calculated survival rates remain significant (P < .0001); however, some strata may have very similar outcomes. Figures 5 and 6 show 5-year survival outcomes for each stage III subgroup stratified by treatment modality (surgery alone vs. surgery plus chemotherapy). Figure 7 shows survival outcomes stratified by patient age (<70 vs. 70 and older). Tumor grade (well or moderately differentiated [grade 1/2] vs. poorly differentiated or undifferentiated [grade 3/4]) outcomes are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 3. Five-year observed survival rates: stage III colon cancers by AJCC 6th edition subgroup, cases diagnosed 1987 to 1993.

Figure 4. Five-year observed survival rates: stage III colon cancers by tumor location and AJCC 6th edition subgroup, cases diagnosed 1987 to 1993. R, right colon; T, transverse colon; L, left colon.

Figure 5. Five-year observed survival rates: stage III colon cancers treated by surgery alone by AJCC 6th edition subgroup, cases diagnosed 1987 to 1993.

Figure 6. Five-year observed survival rates: stage III colon cancers treated surgically with adjuvant chemotherapy by AJCC 6th edition subgroup, cases diagnosed 1987 to 1993.

Figure 7. Five-year observed survival rates: stage III colon cancers by patient age and AJCC 6th edition subgroup, cases diagnosed 1987 to 1993.

Figure 8. Five-year observed survival rates: stage III colon cancers by tumor grade and AJCC 6th edition subgroup, cases diagnosed 1987 to 1993.

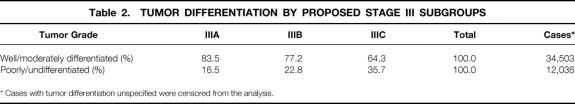

A multivariate Cox proportional hazards model identified four covariates as being independently significantly associated with patient outcomes. These covariates, in descending order of associated significance with patient survival, are stage III subgroups, patient age, tumor grade, and first-course therapy modality (Table 1). The hazards ratio for patients diagnosed with stage IIIB and IIIC tumors was 1.37 and 1.90, respectively, that of patients having stage IIIA disease. Patient age may be considered a proximal representation of patient comorbid conditions and can affect treatment management decisions. 13 Decreasing tumor differentiation (higher tumor grade) is associated with increased stage of disease at diagnosis 14 (Table 2).

Table 1. COVARIATES ASSOCIATED WITH PATIENT SURVIVAL

* Cases with missing values in any of the covariates were censored from the analysis.

Table 2. TUMOR DIFFERENTIATION BY PROPOSED STAGE III SUBGROUPS

* Cases with tumor differentiation unspecified were censored from the analysis.

DISCUSSION

The TNM system espoused by Pierre Denoix of France in the 1940s 15 has remained an important prognostic indicator for most solid tumors. For colorectal cancer, staging strategies recommended by Cuthbert Dukes 16 and modified by Kirklin et al 17 and Astler and Coller 18 were based on careful analyses of mural involvement and the presence of regional nodal involvement, although the number of regional nodes involved was not considered. Careful pathologic assessment of lymph nodes in the colonic mesentery was supported by the work of Gilchrist and David 19 in the 1930s and 1940s. They equated node positivity with decreased survival and championed the concept that extensive mesenteric resection leads to more complete nodal analysis and potentially better survival. Unfortunately, these reports lacked any cohesive strategy for staging based on analysis of the operative specimens.

The presence of positive regional nodes has been the descriptor that has stratified patients with colon cancer into the TNM stage III group as described by the AJCC and UICC. Prior reports have shared concern regarding the potential “prognostic in-homogeneity” of the traditional stage III designation. Merkel et al 3 recently described 1,453 patients representing two cohorts of colorectal carcinoma from the Erlangen Registry of Colorectal Carcinomas and the Study Group of Colorectal Carcinoma. These data sets, while spanning from 1978 to 1997, contained only 665 patients with colon carcinoma. Stage III patients were stratified into T1/2 versus T3 versus T4, with N1/2 held constant. This strategy revealed significant 5-year survival differences based on Kaplan-Meier methodology. More significant survival differences were identified when T1/2, N1 and T3/4, N1 subgroups were compared. In the German cohort of patients, division of N2 patients (four or more positive nodes) into T1/2, N2 and T3/4, N2 showed meaningful survival differences. Various permutations of the T and N category are capable of showing survival differences on subgroup analysis of stage III. The present study shows the most robust differentiation among three groups, with the N2 subgroup deserving a separate delineation from any of the T descriptors.

Based on current recommendations 20 of postsurgical adjuvant therapy for patients with node-positive colon cancer, the advantages of adjuvant chemotherapy are apparent for each of the proposed subgroups in the traditional stage III group. There is no evidence that any of the subgroups of stage III should be approached differently regarding the need for postsurgical chemotherapy. Survival figures may support, however, that stage IIIC (any T, N2) patients may benefit from a more aggressive regimen than the current 5-fluorouracil-based therapy.

The inherent value of any cancer staging system is its reproducibility and applicability to current methods of pathologic assessment. Since the stage III group is defined by the identification and quantification of mesenteric nodes, accuracy of staging is directly proportional to the aggressiveness of surgical resection and nodal identification in this group of patients. The AJCC 12 and the College of American Pathologists 21 have recommended examination of at least 12 lymph nodes to assume identification of stage III patients. Goldstein 22 has shown that nodal metastases in patients with T3 tumors were present in 22% of specimens with fewer than 15 identified nodes compared with 85% in specimens with 15 or greater recovered nodes. Patients without nodal metastases also showed a survival advantage when a greater number of nodes were identified, indicating the positive effect of the greater magnitude of mesenteric resection. Other studies 23,24 have suggested additional benchmarks for nodal excision. Although some have supported the concept of “upstaging” patients with stage I or II colon cancer using immunohistochemical identification of lymphatic involvement with or without sentinel node assessment, 25–27 there is no clear evidence to support that treatment decisions should be based on the “microinvasive” stage III patient. 28 The AJCC and UICC continue to recommend that nodal assessment for colon cancer should depend on traditional hematoxylin-eosin techniques. To be relevant, however, the TNM system must be dynamic enough to incorporate changes in molecular or genetic identification if supported by outcomes analysis. Recommendations for subclassifying traditional stage III patients into three new prognostic groups reflect this approach and are included in the sixth edition of the AJCC’s Cancer Staging Manual.12

DISCUSSION

Dr. Alfred M. Cohen (Lexington, KY): Our colleagues in outcomes research routinely deal with cohorts of tens of thousands of patients, while those of us involved with clinical research usually are fairly content with hundreds of patients in our trials. Dr. Greene and his colleagues have used this very robust NCDB to demonstrate the extensive heterogeneity in survival within a single classic stage group; that is, node-positive colon cancer. As chair of the AJCC, Dr. Greene has utilized this and other studies to provide an evidence-based approach to the revision of our cancer staging system. In this one slide, I have given you a small and incomplete list of the potential additional prognostic variables in colon cancer.

I have three specific questions for Dr. Greene.

The data are very compelling, demonstrating the benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy in stage III colon cancer, including all the subsets. What is the value of the substaging that you just presented to us? Is it strictly for stratification of clinical trials? Or can it actually be used when we are practicing retail medicine dealing with an individual patient?

Secondly, the list of additional potential prognostic features and new ones are reported on a monthly basis. How does the AJCC envision trying to integrate these into new staging systems? Will TNM be relevant in the next edition of your book? Or is it going to disappear?

Lastly, since we have heard a lot of history mentioned this morning, Dr. Dukes published 70 years ago the breakdown of staging by the location of the positive nodes contiguous to the tumor or at the apex of the mesentery. Have we totally abandoned such categories in node-positive colon cancer?

I would like to thank the Association for the opportunity to comment on this important paper. Thank you.

Presenter Dr. Frederick L. Greene (Charlotte, NC): Obviously what we try to do in the TNM system is to create a worldwide language of cancer that can be used in clinical trials as well as our day-to-day management of patients. I think that every study that we have seen thus far has shown that the TNM system is the most robust of the prognostic indicators. Our AJCC Colorectal Cancer Task Force, in preparing the sixth edition, reviewed each indicator shown by Dr. Cohen plus another 20 or 25 prognostic indicators. We feel that today, at least from the data that we have reviewed, there is no evidence to suggest that any of these should be introduced into the TNM staging system.

One prognostic factor that we believe is important is the nuclear grade. The grading of these tumors is very important. To answer your first question, I think that in looking at large data sets, this is the language we should use, but it also is the language for the individual patient. I think by utilizing this new subcategorization of stage III colon cancer, we are probably going to find out that there is a significant difference in the node-positive group. There should be differences in how these patients are treated. The data do not show that any of these patients should have their adjuvant therapy omitted, as suggested by the German study. I think this is a very, very important difference.

Your other question asked about the former Dukes classification. It is interesting that in the first four editions of the AJCC staging manual edited by Dr. Oliver Beahrs, there was an N3 category indicating nodal involvement surrounding the major mesenteric vessels. This was omitted in the fifth edition. But I think that any nodal involvement outside the local regional area is important. We continue to reanalyze nodal location. In the new sixth edition we are listing all of the regional nodes that are important.

Since many of you also are editors or serve on editorial boards and are journal reviewers, I think one of the issues that we need to think about is that when papers dealing with cancer issues are submitted to our journals, these manuscripts ought to be in the language that we use today in the TNM system. I would urge that this criterion for publication be met in future submissions.

Footnotes

Presented at the 122nd Annual Meeting of the American Surgical Association, April 24–27, 2002, The Homestead, Hot Springs, Virginia.

Correspondence: Frederick L. Greene, MD, Department of General Surgery, Carolinas Medical Center, P.O. Box 32861, Charlotte, NC 28232-2861.

E-mail: frederick.greene@carolinashealthcare.org

Accepted for publication April 24, 2002.

References

- 1.Hutter RVP. At last: worldwide agreement on the staging of cancer. Arch Surg 1987; 122: 1235–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fleming ID, Cooper JS, Henson DE, et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1997.

- 3.Merkel S, Mansmann U, Papadopoulos T, et al. The prognostic inhomogeneity of colorectal carcinomas stage III: a proposal for subdivision of Stage III. Cancer 2001; 92: 2754–2759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jessup JM, Menck HR, Winchester DP, et al. The National Cancer Data Base report on patterns of hospital reporting. Cancer 1996; 78: 1829–1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Menck HR, Bland KI, Scott-Conner CE, et al. Regional diversity and breadth of the National Cancer Data Base. Cancer 1998; 83: 2649–2658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Menck HR, Cunningham MP, Jessup JM, et al. The growth and maturation of the National Cancer Data Base. Cancer 1997; 80: 2296–2304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beahrs OH, Henson DE, Hutter RVP, et al. AJCC Manual for Staging of Cancer, 3d ed. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1988.

- 8.Beahrs OH, Henson DE, Hutter RVP, et al. AJCC Manual for Staging of Cancer, 4th ed. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1992.

- 9.Marubini E, Valsecchi MG. Analyzing Survival Data From Clinical Trials and Observational Studies. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1995.

- 10.Cox DR. Regression models and life tables. JR Stat Soc (B) 1972; 34: 187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Survival Analysis. Regression Modeling of Time to Event Data. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1999.

- 12.Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming ID, et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 6th ed. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2002.

- 13.O’Brien KA, Chen VW, Wingo PA, et al. Patterns of care for stage III colon cancer: variations in the use of adjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer, In press.

- 14.Jessup JM, McGinnis LS, Steele GD, et al. The National Cancer Data Base report on colon cancer. Cancer 1996; 78: 918–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sobin LH, Wittekind Ch. The history of the TNM system. In Sobin LH, Wittekind C, eds. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours, 5th ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1997: 1–4.

- 16.Dukes CE, Bussey HJR. The spread of rectal cancer and its effect on prognosis. Br J Cancer 1958; 12: 309–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirklin JW, Dockerty MD, Waugh JW. The role of the peritoneal reflection in the prognosis of carcinoma of the rectum and sigmoid colon. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1949; 88: 326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Astler VB, Coller FA. The prognostic significance of direct extension of carcinoma of the colon and rectum. Ann Surg 1954; 139: 846–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilchrist RK, David VC. A consideration of pathological factors influencing 5-year survival in radical resection of the large bowel and rectum for carcinoma. Ann Surg 1947; 126: 421–438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benson AB, Choti MA, Cohen AM, et al. NCCN practice guidelines for colorectal cancer. Oncology 2000; 14: 203–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Compton CC, Fielding LP, Burgart LJ, et al. Prognostic factors in colorectal cancer. College of American Pathologists consensus statement. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2000; 124: 979–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldstein NS. Lymph node recoveries from 2,427 pT3 colorectal resection specimens spanning 45 years: Recommendations for a minimum number of recovered lymph nodes based on predictive probabilities. Am J Surg Pathol 2002; 26: 179–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cianchi F, Palomba A, Boddi V, et al. Lymph node recovery from colorectal tumor specimens: Recommendation for a minimum number of lymph nodes to be examined. World J Surg 2002; 26: 384–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Wyk Q, Hosie KB, Balsitis M. Histopathological detection of lymph node metastases from colorectal carcinoma. J Clin Pathol 2000; 53: 685–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saha S, Bilchik A, Wiese D, et al. Ultrastaging of colorectal cancer by sentinel lymph node mapping technique: a multicenter trial. Ann Surg Oncol 2001; 8 Suppl: 94–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yasuda K, Adachi Y, Shiraishi N, et al. Pattern of lymph node micrometastasis and prognosis of patients with colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2001; 8: 300–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miyake Y, Yamamoto H, Fujiwara Y, et al. Extensive micrometastases to lymph nodes as a marker for rapid recurrence of colorectal cancer: a study of lymphatic mapping. Clin Cancer Res 2001; 7: 1350–1357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tschmelitsch J, Klimstra DS, Cohen AM. Lymph node micrometastases do not predict relapse in Stage II colon cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2000; 7: 601–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]