Abstract

Objective

Using a prospective randomized study to assess postoperative morbidity and pancreatic function after pancreaticoduodenectomy with pancreaticojejunostomy and duct occlusion without pancreaticojejunostomy.

Summary Background Data

Postoperative complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy are largely due to leakage of the pancreaticoenterostomy. Pancreatic duct occlusion without anastomosis of the pancreatic remnant may prevent these complications.

Methods

A prospective randomized study was performed in a nonselected series of 169 patients with suspected pancreatic and periampullary cancer. In 86 patients the pancreatic duct was occluded without anastomosis to pancreatic remnant, and in 83 patients a pancreaticojejunostomy was performed after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Postoperative complications were the endpoint of the study. All relevant data concerning patient demographics and postoperative morbidity and mortality as well as endocrine and exocrine function were analyzed. At 3 and 12 months after surgery, evaluation of weight loss, stools, and the use of antidiabetics and pancreatic enzyme was repeated.

Results

Patient characteristics were comparable in both groups. There were no differences in median blood loss, duration of operation, and hospital stay. No significant difference was noted in postoperative complications, mortality, and exocrine insufficiency. The incidence of diabetes mellitus was significantly higher in patients with duct occlusion.

Conclusions

Duct occlusion without pancreaticojejunostomy does not reduce postoperative complications but significantly increases the risk of endocrine pancreatic insufficiency after duct occlusion.

Since the first pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic cancer more than 100 years ago, the morbidity rate has been high and the cure rate low. 1,2 The current lower mortality rates have increased interest in this procedure. 3–5 It is now accepted for a variety of malignant as well as benign diseases. Recently pancreaticoduodenectomy was even suggested as a palliative procedure. 6–8 Although operative mortality has decreased to an acceptable level in some centers, morbidity is still high. Serious complications are largely due to leakage of the pancreaticojejunostomy.

Pancreatic fistulas and pancreatitis may develop in the pancreatic remnant and may lead to hemorrhage, sepsis, and subsequent death. Procedures to avoid pancreaticojejunostomy were described, including total pancreatectomy. 9–14 None of these has so far proven to diminish morbidity significantly. Another technique investigated is obliteration closure of the pancreatic duct with a chemical substance, thus avoiding a pancreaticojejunostomy. This method was proposed by Gebhardt et al. 15 They studied the effect of occlusion of the pancreatic duct system with Ethibloc, an alcoholic prolamine, in animal experiments. The pancreatic duct may also be occluded with a fibrin glue solution, Tissucol, which was found to have a more protective effect on beta cell function than the other solutions used. 16 Di Carlo et al 17 described lower morbidity and mortality in a nonrandomized trial in 50 patients using duct occlusion with Neoprene after Whipple’s procedure. Gail et al found similar results with duct occlusion after Whipple’s operation in patients with chronic pancreatitis. 18 Lorenz et al noted fewer early complications in oncologic pancreatic surgery, but not in patients with chronic pancreatitis. 19 These nonrandomized studies have not led to widespread use of duct occlusion in pancreatic surgery. An obvious disadvantage of duct occlusion seems to be the introduction of exocrine insufficiency, which however also occurs after the classical Whipple resection with pancreaticojejunostomy in 9% to 20% of cases. 16,20 One prospective randomized study has been published, albeit with a small number of patients. 21 There was no operative mortality in the 17 patients without pancreaticojejunostomy versus 11% in patients with a pancreatic anastomosis. However, the number of patients in this study was too small to provide evidence that a pancreaticojejunostomy should be abandoned.

The objective of this prospective randomized trial was to investigate postoperative mortality, morbidity, and hospital stay in patients with either a pancreaticojejunostomy or duct occlusion without anastomosis after pancreaticoduodenectomy. In addition, we studied the endocrine and exocrine function of the pancreatic remnant in the two groups of patients.

METHODS

Between July 1994 and September 1998, 169 patients were included in this study: 90 patients in the Hospital San Rafaelle, Italy, and 79 patients in the Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands. Preoperative evaluation consisted of ultrasound and spiral triphase CT scan of the upper abdomen, an ERCP in most patients, with endoscopic placement of an endoprosthesis, and a chest X-ray. A blood glucose value was requested to evaluate endocrine function. Preillness body weight and preoperative body weight were recorded.

All patients undergoing a pancreaticoduodenectomy for suspected pancreatic cancer and periampullary cancer were randomized if both procedures, occlusion of the pancreatic duct and pancreaticojejunostomy, were possible. Randomization took place during surgery. In 86 patients the pancreatic duct was occluded, and in 83 patients a pancreaticojejunostomy was performed after pancreaticoduodenectomy. The patients underwent either a classical Whipple resection or pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy.

Occlusion of the pancreatic duct was obtained by injection of Ethibloc (n = 18), Neoprene (n = 45), or Tissucol (n = 23) in combination with aprotinin (Trasylol). Neoprene was used in Milan; Ethibloc and Tissucol were used in Rotterdam. After obliteration of the pancreatic duct, the opening of the duct was ligated with 3-0 polydoxanone suture (PDS) and the pancreatic remnant was sewn up. A non-suction silicone drain was placed near the pancreatic remnant and gradually retracted after 7 days. In Milan, a two-layer pancreaticojejunostomy with Monocryl 4-0 running suture was used for the external layer, and Monocryl 5-0 interrupted suture was used for the duct mucosa anastomosis. In Rotterdam a one-layer running PDS suture was used for the end-to-side telescopic pancreaticojejunostomy. No duct-to-mucosa anastomosis was made.

Ethibloc (Johnson & Johnson) is an alcoholic prolamine solution that hardens in 15 to 20 minutes in a moist environment; it is microbiologically indifferent and becomes disintegrated within 11 days. Neoprene latex 671 (Dupont de Nemours) is a liquid synthetic rubber composed of polychlorprene homopolymer. When in contact with the pancreatic juice (pH 8–9), Neoprene polymerizes and hardens. Tissucol (Immuno GmbH) is a modified fibrin glue solution, and in combination with thrombin (Trasylol) it will harden. The solution dissolves in about 7 days.

After surgery the surgeon completed a report including the operation indication, operation technique, consistency of the pancreas, diameter of the pancreatic duct, intraoperative complications, and parameters in terms of blood loss, number of blood transfusions during the operation, and length of operation. On discharge (or in case of hospital death), a form was completed to evaluate postoperative complications, exocrine pancreatic function, frequency and aspect of stools, body weight on discharge, and the need for pancreas enzyme substitution therapy. Furthermore, endocrine function was evaluated by measuring glucose values on postoperative days 5 and 7 and on discharge, and the need for antidiabetic tablets or insulin. At 3 and 12 months after operation, the evaluation of weight loss, frequency and aspect of stools, and the use of antidiabetic medicine and pancreatic enzymes was repeated.

For the purpose of this study operative mortality was defined as mortality during the postoperative admission period, within 30 days after surgery. The primary endpoints were postoperative complications, defined as follows:

Leakage of pancreatic, biliary, or intestinal anastomosis (determined radiologically as well as during rela-parotomy)

Pancreatic fistula was diagnosed when drainage of abdominal fluid with amylase and lipase concentrations was three times higher than the serum concentration.

An intraabdominal abscess was defined as an infected fluid collection revealed by ultrasound or CT-guided needle aspiration or relaparotomy and microbiological culture.

Bleeding was defined as the replacement of more than three units of blood after the first 24 hours after surgery or relaparotomy.

Statistics

The primary endpoint of this study was the total number of recorded postoperative surgical complications. To reach significance with a power of 80% and a reduction of postoperative complications from 20% to 5%, we had to include at least 75 patients per group. Chi-square test, two-by-two cross tables, and Fisher exact test were used for the statistical analysis. Survival was evaluated by the Kaplan-Meier test. All probability values were two-tailed, and a value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

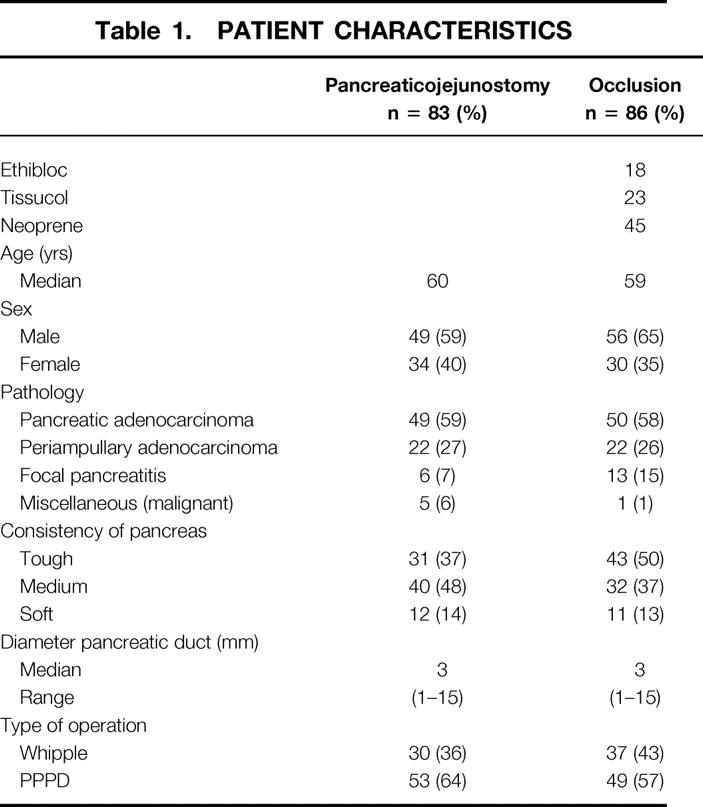

Included in the study were 83 patients with a pancreaticojejunostomy and 86 patients with chemical occlusion of the pancreatic duct after pancreaticojejunostomy. In Table 1 the clinical characteristics of the 169 patients included in this study are presented. All the characteristics were comparable between both groups. In the group with a “miscellaneous” malignancy, two patients had a cholangiocarcinoma, one patient had an endocrine malignant tumor, one patient had a metastasis of a Grawitz tumor, one patient had a carcinoid, and one patient had a carcinoma of the duodenum.

Table 1. PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS

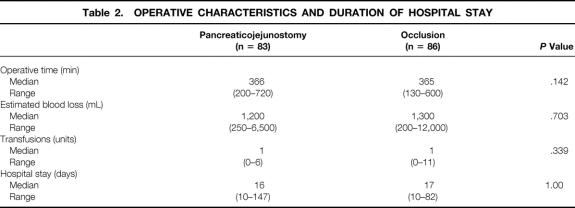

The data concerning intraoperative blood loss, number of blood transfusions during operation, duration of operation, and hospital stay are shown in Table 2. These parameters were similar for the two groups.

Table 2. OPERATIVE CHARACTERISTICS AND DURATION OF HOSPITAL STAY

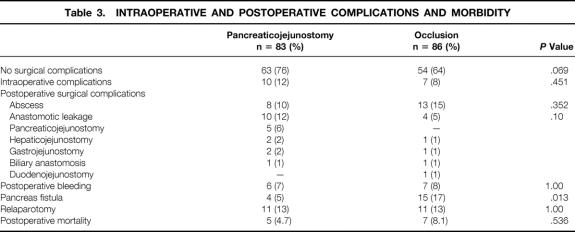

Intraoperative and postoperative complications due to bleeding, postoperative surgical complications, and number of patients with one or more relaparotomies are summarized in Table 3. Of the patients who underwent a relaparotomy, four patients in the pancreaticojejunostomy group and five patients in the occlusion group died within 30 days after pancreaticoduodenectomy. There was no relationship between pancreas consistency and complications. There was no significant difference in postoperative complications. In the group of patients with pancreaticojejunostomy, 63 (76%) had no postoperative complication versus 54 (64%) in the patients with duct occlusion (P = .069) The incidence of postoperative pancreatic fistula was significantly higher in the duct occlusion group (P = .013).

Table 3. INTRAOPERATIVE AND POSTOPERATIVE COMPLICATIONS AND MORBIDITY

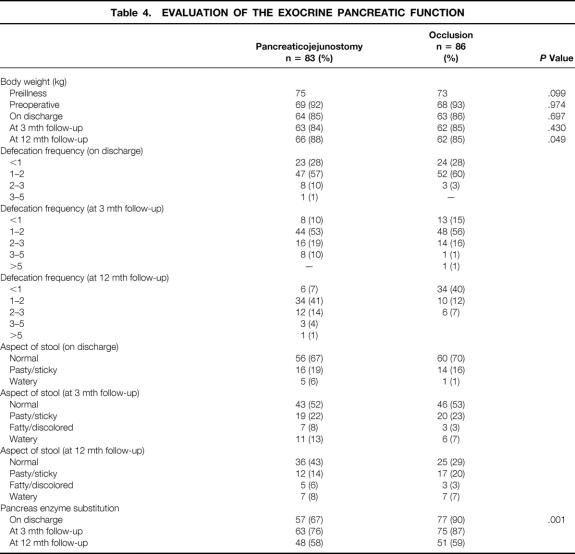

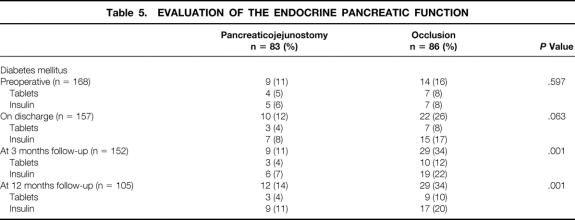

Information about the exocrine pancreatic function and theendocrine pancreatic function is presented respectively in Table 4 and Table 5. There was no significant difference betweenboth groups concerning defecation frequency and/or aspect of stools. Patients with a pancreaticojejunostomy were still gaining weight at 12 months, whereas in patients in the occlusion group the body weight stayed the same. The changes in body weight are expressed as percentages of preillness body weight (see Table 4). Pancreas enzyme substitution was, on discharge and at 3 months, significantly higher in patients with occlusion of the pancreatic duct (P = .001 and P = .003), but not different at 12 months. There was no statistical analysis possible at 12 months regarding the defecation frequency and aspects of stools because there were too many data missing. Table 5 shows the occurrence of diabetes mellitus: it was significantly higher in patients with occlusion of the pancreatic duct (P = .001).

Table 4. EVALUATION OF THE EXOCRINE PANCREATIC FUNCTION

Table 5. EVALUATION OF THE ENDOCRINE PANCREATIC FUNCTION

The overall actuarial survival rate for patients undergoing pancreaticojejunostomy was 69% versus 63% for patients undergoing chemical pancreatic duct occlusion after pancreaticojejunostomy. At 1 year, survival rates in patients with a malignant disease after pancreaticoduodenectomy and subsequently pancreaticojejunostomy versus duct occlusion were respectively 66% and 58%.

Postoperative mortality, within 30 days after surgery, was 4.7% in the pancreaticojejunostomy group and 8.1% in the pancreatic duct occlusion group (P = .536). In all cases of duct occlusion pancreatic leakage was the main cause of death. In the Ethibloc group, five cases of sepsis and bleeding from pancreatitis with subsequent leakage were encountered, which led to a high mortality rate in this group of patients in Rotterdam.

DISCUSSION

Failure of a surgical anastomosis has serious consequences, particularly in case of anastomosis of the pancreas to the small bowel, because of the digestive capacities of activated pancreatic secretions. An important factor in the prevention of pancreatic fistula in patients with a pancreaticojejunostomy is technical precision and gentleness in construction of the pancreatic anastomosis. A dilated pancreatic duct in a fibrotic pancreas may decrease the incidence of postoperative fistula. 12,20,22,23

The absence of an anastomosis to the pancreatic remnant may prevent a large part of the postoperative complications. A pancreatic fistula from the oversewn pancreatic remnant is less dangerous than one from the pancreaticojejunal anastomosis 12,20,23,24 because there is no defect in the small bowel and no activation of pancreatic enzymes. Another option is total pancreatectomy. Induction of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus is a major disadvantage of total pancreatectomy. This apancreatic diabetes can lead to severe episodes of hypoglycemia that can be difficult to manage and can even lead to death. 11,25,26

Occlusion of the pancreatic stump with synthetic or biologic substances to suppress exocrine pancreatic secretion has been proposed as a safe alternative to pancreaticojejunostomy. 23 Pancreatic duct occlusion after resection may reduce early complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy and protect the beta cell function in the remaining pancreas. 18,27,28 So far no evidence exists that a pancreaticoenterostomy can be safely replaced by duct obliteration, although this was suggested in a number of studies.

We conducted a prospective randomized trial to study the effect of duct occlusion without creating an anastomosis. The primary endpoint of this study was the following postoperative surgical complications: anastomotic leakage, pancreatic fistula, intraabdominal abscess, and postoperative bleeding.

There were intraoperative complications in 10% of patients in the pancreaticojejunostomy group and 7% of patients in the occlusion group (P = .451). Sixty-three (76%) patients with an anastomosis versus 54 (64%) patients with duct occlusion had no surgical complication (P = .069). The only surgical complication with a significantly higher incidence was a pancreatic fistula in the duct occlusion group (P = .013). The same number of patients needed a relaparotomy. Postoperative mortality was comparable between both groups: four patients in the anastomosis group versus seven in the occlusion group (P = .536). At 3- and 12-month follow-up, the survival rates were comparable.

We found no significant difference in the statistical analysis among the three kinds of chemical substances (Ethibloc, Neoprene, Tissucol) we used in the duct occlusion group, but there was a trend towards a higher mortality rate in case of duct occlusion with Ethibloc. Ethibloc and Neoprene induce exocrine atrophy of the pancreatic remnant. 18,19,29 All patients will temporarily completely lose their exocrine pancreatic function. A study by Braga et al showed that the combination of enzyme replacement therapy and low-fat diet allows adequate correction of steatorrhea and a significant improvement in nutritional status. 2,26,30 As for the endocrine function, there were no differences among the three kinds of chemical substances used; the incidence of diabetes was not different based on the substance used. There was no significant difference between both groups in defecation frequency and aspects of stools on discharge at 3 and 12 months of follow-up. The number of patients who used pancreatic enzyme substitution was significantly higher in the duct occlusion group in the early postoperative period but not at 12 months. Surprisingly, at 12 months, enzyme substitution was used in only 59% of the patients with duct occlusion. The body weight in the occlusion group patients showed a trend at 12 months of follow-up of stabilization at 85% of their original body weight, whereas the patients with pancreaticojejunostomy still gained weight (P = .05).

According to the literature, the function of the islets of Langerhans is not affected by chemical duct occlusion. 18,29,31,32 Konishi et al 22 suggested that in the long term the use of occlusion-emulsion may cause atrophy of the pancreatic parenchyma in the occluded segment; consequently, the risk of diabetes mellitus with this procedure must be considered. In experiments with dogs, Gooszen et al found that the destruction of islet architecture led to about 70% reduction of the insulin-secreting capacity. 30 After 3 months and also after 12 months there were significantly more patients with diabetes mellitus in the occlusion group than in the group with a pancreaticojejunostomy (P = .001). All patients were well regulated with antidiabetic tablets or insulin.

In conclusion, there are no advantages in avoiding a pancreaticojejunostomy. Duct obliteration without anastomosis does not reduce postoperative complications. A pancreatic surgeon must be able to perform more than one technique for managing the pancreatic remnant, especially in the case of a small pancreatic duct and a soft friable pancreatic remnant. The method of choice remains a pancreaticoenterostomy because of the significantly higher risk of endocrine insufficiency in case of duct occlusion.

DISCUSSION

Dr. John S. Najarian (Minneapolis, MN): I enjoyed the paper, and it is interesting to see the kind of results you have achieved. The problems that I have with the paper, though, take several forms.

First, in looking at our own series of pancreatic transplants (and maybe it is not fair to compare), but in over 1,500 pancreas transplants, we tried in 41 cases early on to do duct occlusion using polymers. We found that with time, the pancreas eventually developed a degree of pancreatitis that would lead to destruction of beta cells and development of endocrine insufficiency.

As a result, we gave up the technique of duct occlusion and only performed pancreatic drainage. We drained the pancreas into either the bladder or the intestines and obtained excellent results. As a matter of fact, we recently looked at over 100 such recipients who are now well past 10 years posttransplant with excellent endocrine function.

Second, I was a little concerned about this fact: when you did a pancreaticojejunostomy, your eventual exocrine function was no different from when you completely occluded the duct. This fact indicated to me that, somehow or other, your anastomosis must have failed or stenosed, that there was a problem with the anastomosis. I would like to have your thoughts on that and on this discrepancy. Why was there a decrease in exocrine function in the group that was supposed to be draining into the intestine?

Third, did you find, in those patients with an occlusion of the pancreatic duct, that the incidence of diabetes progressively increased? In other words, did you see a progressive decrease in the amount of insulin they were producing (as we reported when we occluded the duct in our pancreas transplant experience)?

I enjoyed the paper. But I would hope that we continue to do pancreaticoenterostomies because I think we do them for a reason. It is not because of exocrine function, which we can make up for by oral enzyme replacement. Rather, we do them to avoid diabetes if at all possible. And it is possible to avoid diabetes in these patients.

Presenter Dr. J. Hans Jeekel (Rotterdam, Netherlands): Dr. Najarian, that is exactly the reason why we promote the performance of a pancreaticojejunostomy. The conclusions of these data are the same as yours, in fact, but now proven in a prospective randomized fashion. So we have definitely demonstrated that a pancreatic surgeon should perform an anastomosis of the pancreatic remnant. The reason is that there is no difference in postoperative morbidity whether an anastomosis is made or not, but that the endocrine insufficiency is significantly greater in case of occlusion of the duct and absence of anastomosis, although there was no difference in exocrine sufficiency. You were surprised by the fact that there was no difference in exocrine insufficiency, but you have to realize that in the occlusion group in 31% of the patients, pancreatic enzymes were not used postoperatively; apparently a considerable number of patients did not need enzyme substitution. Thus, the study for the first time gives evidence-based arguments in favor of the performance of a pancreatic enterostomy.

Dr. Gerard V. Aranha (Maywood and Hines, IL): Dr. Jeekel, I enjoyed your paper and agree with your conclusions and would like to share our data on the quality of life following pancreaticoduodenectomy. At our institution, two surgeons do most of the pancreaticoduodenectomies and one does a pancreaticojejunostomy and the other pancreaticogastrostomy.

Questionnaires on quality of life were sent to 118 surviving patients and 95 (81%) responded. We found that 45% of our patients were able to stop using exocrine pancreatic enzymes and that only nine (10%) patients became diabetic after the operation. We strongly feel that an anastomosis after a pancreaticoduodenectomy is better than obliterating the duct with glue. I wonder if you would consider in your next study a prospective randomized comparison of the quality of life after the Whipple operation in a group of patients, half randomized to pancreaticojejunostomy and the other half to pancreaticogastrostomy?

Dr. J. Hans Jeekel (Rotterdam, Netherlands): I am a little puzzled by the questions about the advice to do anastomosis. That was just the conclusion of this study; that is just what I do advise. So I do not advise to do an occlusion. I think that that was absolutely clear from the study.

Dr. Aranha, you do have less diabetes apparently than we have. We try to evaluate very carefully before operation and after operation up to 12 months so we have data before and after operation. Maybe after 1 year there will be more difference, but not less difference, I would say.

Dr. John M. Howard (Toledo, OH): This is a very interesting series of patients you have reported. Thank you. May I call your attention to two reports from our laboratory? One, in Annals of Surgery in 1973, with Dr. Anne Ambromovage as senior author, was entitled “Pancreatic Exocrine Insufficiency: The Effects of Long-Term Pancreatic Duct Ligation on Serum Insulin Levels and Glucose Metabolism in the Dog.” The study revealed the gradual fall in fasting serum insulin levels after ductal ligation. At the same time, a subnormal response in serum insulin levels followed oral glucose and was associated with a diabetic-type glucose tolerance curve. Histologically, the islets of Langerhans tended to disappear or to become unrecognizable, although immunoassayable insulin did not completely disappear from the serum.

The second paper, which I authored in The Journal of the American College of Surgeons in May 1997, was entitled “Pancreatojejunostomy: Leakage is a Preventable Complication of the Whipple Resection.” Fifty-six consecutive pancreatojejunostomies included intubation of the pancreatic anastomosis in such a way that pure pancreatic juice could be collected in the immediate weeks after resection. Many of those patients had preoperative obstruction of the pancreatic and common bile ducts. Postoperative collection of pancreatic juice from the transanastomotic catheter, its apertures lying within the pancreatic duct, demonstrated normal concentration of amylase in the juice throughout the initial days or weeks. The exocrine cells of such a pancreas had maintained their capability of resuming function following relief of obstruction to its outflow.

Dr. J. Hans Jeekel (Rotterdam, Netherlands): Thank you for your questions, Dr. Howard. I am aware of your studies. There was one other study, too, of Dr. Gooszen, who demonstrated in animal studies that the incidence that duct obliteration could induce diabetes. Now with this clinical study we have demonstrated that in man, too. Of course you have to consider besides diabetes also the other postoperative complications like abscess, bleeding, mortality, etc. In our prospective randomized study we did not find a difference in postoperative morbidity and mortality, only in the occurrence of diabetes. For this reason we advise not to avoid the anastomosis by duct obliteration, but always to do a pancreaticoenterostomy.

Footnotes

Presented at the 122nd Annual Meeting of the American Surgical Association, April 24–27, 2002, The Homestead, Hot Springs, Virginia.

Correspondence: Hans Jeekel, MD, PhD, Department of Surgery, Erasmus Medical Centre Rotterdam, Dr. Molewaterplein 40, 3015 GD Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

E-mail: jeekel@hlkd.azr.nl

Accepted for publication April 24, 2002.

References

- 1.Trede M. [Guidelines in therapy of pancreatic carcinoma]. Langenbecks Arch Chir Suppl Kongressbd 1997; 114: 156–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trede M, Wendl K, Richter A. [Pancreatic carcinoma–conclusions and prospects]. Langenbecks Arch Chir Suppl Kongressbd 1998; 115: 411–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooperman AM. Pancreatic cancer: the bigger picture. Surg Clin North Am 2001; 81: 557–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gebhardt C. Surgical treatment of pain in chronic pancreatitis. Role of the Whipple procedure. Acta Chir Scand 1990; 156: 303–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lai EC, Chu KM, Lo CY, et al. Surgery for malignant obstructive jaundice: analysis of mortality. Surgery 1992; 112: 891–896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lygidakis NJ, van der Hyde MN, Houthoff HJ, et al. Resectional surgical procedures for carcinoma of the head of the pancreas. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1989; 168: 157–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watanapa P, Williamson RC. Surgical palliation for pancreatic cancer: developments during the past two decades. Br J Surg 1992; 79: 8–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watanapa P, Williamson RC. Single-loop biliary and gastric bypass for irresectable pancreatic carcinoma. Br J Surg 1993; 80: 237–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farley DR, Schwall G, Trede M. Completion pancreatectomy for surgical complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Br J Surg 1996; 83: 176–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ihse I, Lilja P, Arnesjo B, et al. Total pancreatectomy for cancer. An appraisal of 65 cases. Ann Surg 1977; 186: 675–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ihse I, Anderson H, Andren S. Total pancreatectomy for cancer of the pancreas: is it appropriate? World J Surg 1996; 20: 288–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Papachristou DN, Fortner JG. Pancreatic fistula complicating pancreatectomy for malignant disease. Br J Surg 1981; 68: 238–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trede M. Treatment of pancreatic carcinoma: the surgeon’s dilemma. Br J Surg 1987; 74: 79–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Heerden JA, ReMine WH, Weiland LH, et al. Total pancreatectomy for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Mayo Clinic experience. Am J Surg 1981; 142: 308–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gebhardt C, Stolte M, Schwille PO, et al. Experimental studies on pancreatic duct occlusion with prolamine. Horm Metab Res Suppl 1983: 9–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Idezuki Y, Goetz FC, Lillehei RC. Late effect of pancreatic duct ligation on beta cell function. Am J Surg 1969; 117: 33–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Di Carlo V, Chiesa R, Pontiroli AE, et al. Pancreatoduodenectomy with occlusion of the residual stump by Neoprene injection. World J Surg 1989; 13: 105–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gall FP, Zirngibl H, Gebhardt C, et al. Duodenal pancreatectomy with occlusion of the pancreatic duct. Hepato-Gastroenterology 1990; 37: 290–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waclawiczek HW, Boeckl O, Lorenz D. [Pancreatic duct occlusion with fibrin (glue) to protect the pancreatico-digestive anastomosis after resection of the head of the pancreas in oncologic surgery]. Langenbecks Arch Chir Suppl Kongressbd 1996; 113: 252–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shankar S, Theis B, Russell RC. Management of the stump of the pancreas after distal pancreatic resection. Br J Surg 1990; 77: 541–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reissman P, Perry Y, Cuenca A, et al. Pancreaticojejunostomy versus controlled pancreaticocutaneous fistula in pancreaticoduodenectomy for periampullary carcinoma. Am J Surg 1995; 169: 585–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Konishi T, Hiraishi M, Kubota K, et al. Segmental occlusion of the pancreatic duct with prolamine to prevent fistula formation after distal pancreatectomy. Ann Surg 1995; 221: 165–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marcus SG, Cohen H, Ranson JH. Optimal management of the pancreatic remnant after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg 1995; 221: 635–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Papachristou DN, Fortner JG. Management of the pancreatic remnant in pancreatoduodenectomy. J Surg Oncol 1981; 18: 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berge Henegouwen MI, De Wit LT, van Gulik TM, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and treatment of pancreatic leakage after pancreaticoduodenectomy: drainage versus resection of the pancreatic remnant. J Am Coll Surg 1997; 185: 18–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Braga M, Zerbi A, Dal Cin S, et al. Postoperative management of patients with total exocrine pancreatic insufficiency. Br J Surg 1990; 77: 669–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waclawiczek HW, Heinerman M, Meiser G, et al. [Prevention, treatment of postoperative fistulae–new indications for fibrin gluing]. Wien Klin Wochenschr 1992; 104: 474–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zimmermann FA, Pistorius G, Grabowsky K, et al. A new approach to duct management in pancreatic transplantation: temporary occlusion with fibrin sealing and enterostomies. Transplant Proc 1987; 19: 3941–3947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gebhardt C. Pancreaticojejunal anastomosis. Indication, technique and results. Zentralbl Chir 2001; 126: 29–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gooszen HG, Bosman FT, van Schilfgaarde R. The effect of duct obliteration on the histology and endocrine function of the canine pancreas. Transplantation 1984; 38: 13–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gooszen HG, van Schilfgaarde R. Pancreatic duct obliteration: clinical application, morphological and functional effects. Neth J Surg 1987; 39: 19–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gooszen HG, van der Burg MP, Guicherit OR, et al. Crossover study on effects of duct obliteration, celiac denervation, and autotransplantation on glucose- and meal-stimulated insulin, glucagon, and pancreatic polypeptide levels. Diabetes 1989; 38 (Suppl 1): 114–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]