Abstract

Objective

To determine the patient factors affecting patient outcome of first liver retransplantation at a single center to help in the decision process for retransplantation.

Summary Background Data

Given the critical organ shortage, one of the most controversial questions is whether hepatic retransplantation, the only chance of survival for patients with a failing first organ, should be offered liberally despite its greater cost, worse survival, and the inevitable denial of access to primary transplantation to other patients due to the depletion of an already-limited organ supply. The authors’ experience of 139 consecutive retransplantations was reviewed to evaluate the results of retransplantation and to identify the factors that could improve the results.

Methods

From 1986 to 2000, 1,038 patients underwent only one liver transplant and 139 patients underwent a first retransplant at the authors’ center (first retransplantation rate = 12%). Multivariate analysis was performed to identify variables, excluding intraoperative and donor variables, associated with graft and patient long-term survival following first retransplantation. Lengths of hospital and intensive care unit stay and hospital charges incurred during the transplantation admissions were compared for retransplanted patients and primary-transplant patients.

Results

One-year, 5-year, and 10-year graft and patient survival rates following retransplantation were 54.0%, 42.5%, 36.8% and 61.2%, 53.7%, and 50.1%, respectively. These percentages were significantly less than those following a single hepatic transplantation at the authors’ center during the same period (82.3%, 72.1%, and 66.9%, respectively). On multivariate analysis, three patient variables were significantly associated with a poorer patient outcome: urgency of retransplantation (excluding primary nonfunction), age, and creatinine. Primary nonfunction as an indication for retransplantation, total bilirubin, and factor II level were associated with a better prognosis. The final model was highly predictive of survival: according to the combination of the factors affecting outcome, 5-year patient survival rates varied from 15% to 83%. Retransplant patients had significantly longer hospital and intensive care unit stays and accumulated significantly higher total hospital charges than those receiving only one transplant.

Conclusions

These data confirm the utility of retransplantation in the elective situation. In the emergency setting, retransplantation should be used with discretion, and it should be avoided in subgroups of patients with little chance of success.

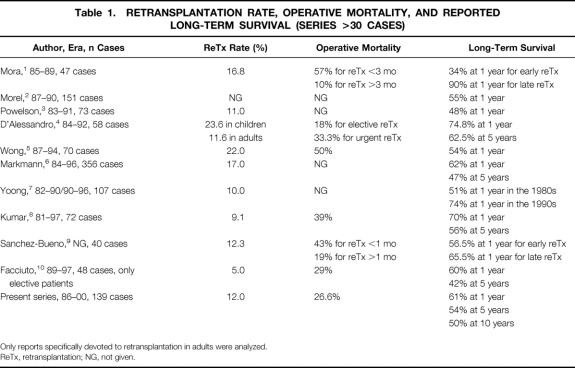

Liver retransplantation is the only therapy for irreversible graft failure and represents 10% to 22% of transplantation activity worldwide 1–10 (Table 1). With the introduction of cyclosporine, liver retransplantation initially played a role in the improvement of survival of liver transplantation. 11,12 Since then, retransplantation has been repeatedly associated with lower survival rates than first transplantation. 1,3,4,12–15 The medical problem is compounded by financial and ethical issues since retransplantation is costly and denies access to transplantation to patients awaiting their first transplant. 3,4,6,16,17

Table 1. RETRANSPLANTATION RATE, OPERATIVE MORTALITY, AND REPORTED LONG-TERM SURVIVAL (SERIES >30 CASES)

Only reports specifically devoted to retransplantation in adults were analyzed.

ReTx, retransplantation; NG, not given.

Practically, the decision regarding retransplantation rests on two considerations: the operative risk of retransplantation and the chance of long-term survival.

Most reports quote perioperative and donor factors as predictors of prognosis when, in fact, these data are not available when listing a patient for retransplantation. The objective of the present study was to identify factors available at the time of decision of retransplantation, thus excluding intraoperative and donor data, with prognostic value for short- and long-term survival, by studying a series of 139 consecutive cases of retransplantation in a single unit.

METHODS

Study Population

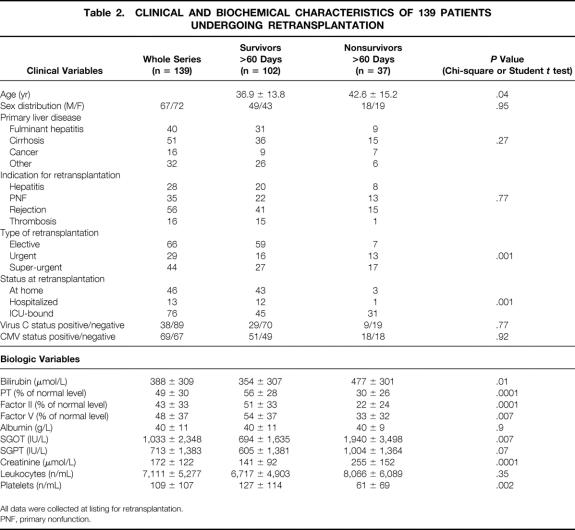

From September 1986 to September 1999, 1,038 patients underwent only one liver transplant (excluding multiorgan transplantation) and 139 patients underwent a first retransplantation at the Paul Brousse Center (first retransplant rate = 12%). Patients undergoing more than one retransplantation (n = 28 cases) were excluded. All data were collected at the time of listing for retransplantation, since the decision to proceed rested on these data. The collected data are listed in Table 2.

Table 2. CLINICAL AND BIOCHEMICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF 139 PATIENTS UNDERGOING RETRANSPLANTATION

All data were collected at listing for retransplantation.

PNF, primary nonfunction.

Primary nonfunction (PNF) was defined as a graft with such poor initial function that retransplantation occurred within 1 week of the primary procedure without any identifiable cause of graft failure. According to the rules of allocation used in France (Etablissement Français des Greffes, dependent on the French Ministry of Health), in the elective situation a liver graft is attributed to a transplant center, which in turn chooses the recipient. Patients on the super-emergency list have absolute priority for any liver graft in France during a period limited to 6 days. Urgent patients are those already transplanted whose condition is rapidly deteriorating on the waiting list. They are put on an intermediate-priority list after approval from experts outside the patient’s center. In the retransplanted group the procedure was elective in 66 cases, urgent in 29 cases, and super-urgent in 44 cases. In the single-transplant group, the procedure was elective in 872 cases and super-urgent in 165 cases.

Data Analysis

Continuous variables in recipients included age (years), pretransplant levels of prothrombin (% of normal level) and coagulation factors II and V (% of normal level), bilirubin (μmol/L), albumin (g/L), creatinine (μmol/L), alanine aminotransferase (IU/L), and aspartate aminotransferase (IU/L). Categorical variables included sex and hospitalization status at transplantation (i.e., in hospital, in ICU, or at home). Variables of potential prognostic importance were assessed by univariate analysis. If significantly correlated with the main end-points (log-rank test), they were evaluated in the Cox proportional hazard model, using forward stepwise selection to identify independent predictive factors. Risk ratios and corresponding 95% confidence intervals were calculated. P < .05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Standard transformations such as square root and natural logarithm were used to decrease the unexplained variation (i.e., nonconstant variance or outliers) and make the distribution of covariates more similar to a normal distribution.

Data from the European Liver Transplant Registry

These data were retrieved from the European Liver Transplant Registry (ELTR), 18 including data from 118 centers in 20 countries. Patient survival rates were calculated for 27,200 cases of single transplantation (23,547 elective and 3,653 urgent cases) and 3,431 cases of first retransplantation (1,389 elective and 1,042 urgent cases) performed from September 1986 to September 1999. These data, retrieved from large samples, were used to validate the Paul Brousse Center analysis.

RESULTS

Follow-Up

None of the patients were lost to follow-up, which ranged from 0 to 170.1 months (51.0 ± 50.1 months) for the retransplanted patients and 0 to 170.0 months (62.0 ± 47.3 months) for the single transplant group.

Patient 60-Day Survival

Thirty-seven of the 139 retransplanted patients died within 60 days of retransplantation (26.6%), representing 54.4% of overall mortality in this group (68 cases). This is significantly higher than the 60-day mortality of the single transplant group (91/1,038 patients [8.9%], P < .0001). The analysis of the ELTR shows similar results (34.7% vs. 13.2%, P < .0001).

When the cause of death was categorized into either septic or nonseptic etiologies, the incidence of death secondary to sepsis was significantly higher in the retransplantation group than in the single transplant group (23/37 [62.2%] vs. 36/91 [39.6%], P = .03). The ELTR shows similar figures (31.0% vs. 23.4%, P < .0001).

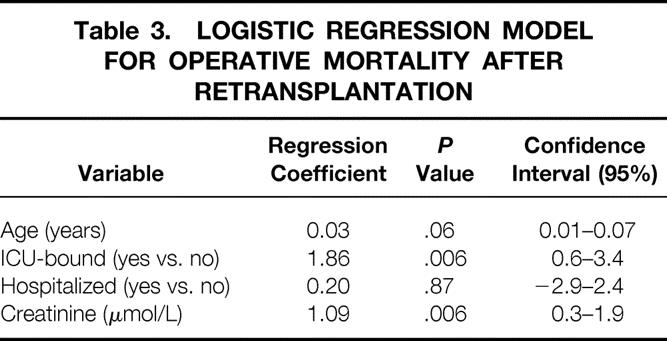

Multivariate analysis showed that the independent predictors of 60-day mortality following retransplantation were age (P = .06), serum creatinine level (P = .006), and when the recipient was ICU-bound before retransplantation (P = .006). Tables 2 and 3 show the results of entering the prognostic variables into univariate (chi-square and Student t test) and multivariate logistic regression models for 60-day patient survival. This model allows calculation of the probability of operative mortality:

Table 3. LOGISTIC REGRESSION MODEL FOR OPERATIVE MORTALITY AFTER RETRANSPLANTATION

prob = 1/(1 + exp -(−9.16 + 0.03*Age + 1.86*ICU-bound + 0.20*Hospitalized + 1.09*loge creatinine), with ICU-bound and hospitalized coded as 1 if yes and 0 if no.

Long-Term Patient Survival

Overall Survival

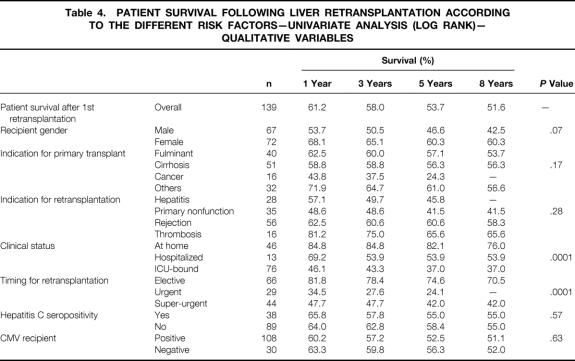

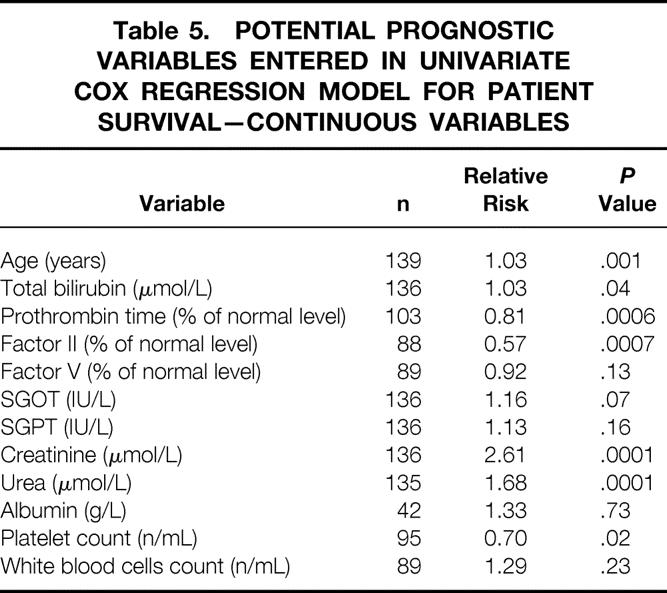

Tables 4 and 5 show the results for categorical and continuous variables.

Table 4. PATIENT SURVIVAL FOLLOWING LIVER RETRANSPLANTATION ACCORDING TO THE DIFFERENT RISK FACTORS—UNIVARIATE ANALYSIS (LOG RANK)— QUALITATIVE VARIABLES

Table 5. POTENTIAL PROGNOSTIC VARIABLES ENTERED IN UNIVARIATE COX REGRESSION MODEL FOR PATIENT SURVIVAL—CONTINUOUS VARIABLES

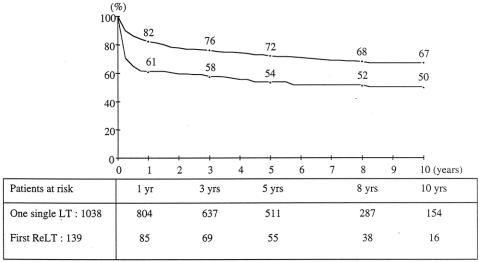

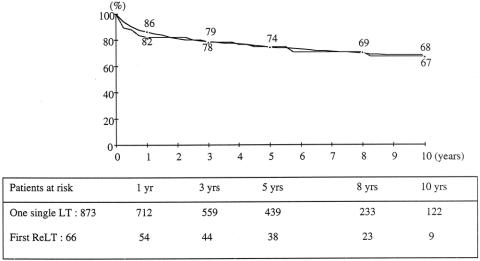

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for each group (139 retransplants, 1,038 single transplants) are shown in Figure 1. For the retransplant group, survival rates from the date of the first transplant at 1, 5, and 10 years were, respectively, 71%, 58%, and 53%; rates from the date of the second graft were 61%, 54%, and 50%. This is less than that of the 1,038 single transplant patients (82%, 72%, and 67%, P = .0001). This is confirmed by the ELTR 1-, 5-, and 10-year rates of 55%, 46%, and 41% for 3,431 retransplanted patients versus 79%, 70%, and 63% for 27,200 single transplant patients during the same study period (P = .0001). The ELTR shows a strong correlation between the number of transplantations performed per year and the outcome of retransplantation: for centers performing less than 25, between 25 and 90, and more than 90 transplantations per year, survival rates following retransplantation were 47%, 39%, and 33% versus 55%, 46%, and 40% versus 58%, 49%, and 47% at 1, 5, and 10 years (P = .0007).

Figure 1. Overall patient survival after a single liver transplant (circles, n = 1,038) versus first retransplantation (triangles, n = 139).

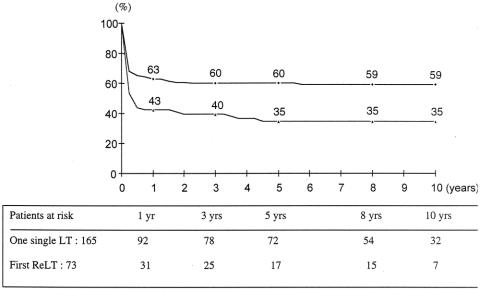

Survival for Elective Patients

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the 66 elective retransplanted patients and for the 873 elective single transplant patients are shown in Figure 2. For the retransplant group, survival rates from the date of the first transplant at 1, 5, and 10 years were 94%, 81%, and 74%; rates from the date of the second graft were 82%, 74%, and 67%. This is comparable to that of the 873 single transplant patients (86%, 74%, and 68%). In contrast, in the ELTR, survival rates following elective retransplantation were significantly lower for retransplantation compared to single transplant (66%, 55%, and 49% vs. 82%, 72%, and 65% at 1, 5, and 10 years, P = .0001).

Figure 2. Patient survival after a single elective liver transplant (circles, n = 873) versus elective retransplantation (triangles, n = 66).

Survival for Urgent Patients

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the 73 emergency (urgent + super-urgent) retransplanted patients and for the 165 emergency single transplant patients are shown in Figure 3. For the retransplant group, survival rates from the date of the first transplant at 1, 5, and 10 years were 51%, 37%, and 33%; rates were 43%, 35%, and 35% from the date of the second graft. This is less than that of the 165 patients transplanted during the study period who required only one emergency transplant (all super-urgent) (63%, 60%, and 59%, P = .002) . The ELTR also shows that survival rates following urgent retransplantation were significantly lower for retransplantation compared to the single transplant group (46%, 39%, and 35% vs. 65%, 59%, and 56% at 1, 5, and 10 years, P = .0001).

Figure 3. Patient survival after a single urgent liver transplant (circles, n = 165) versus urgent retransplantation (triangles, n = 73).

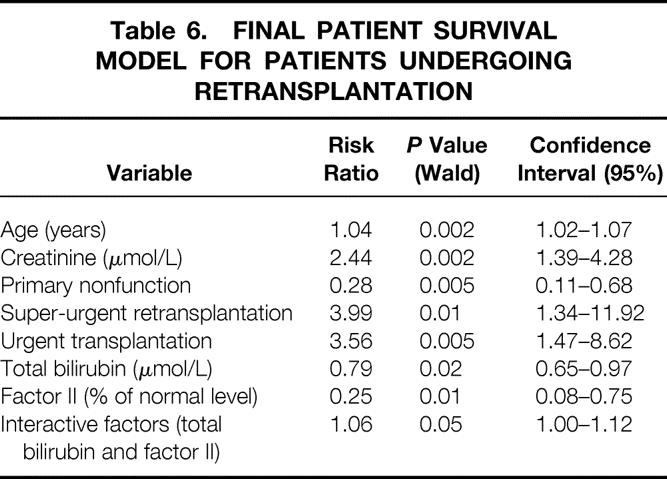

Multivariate Analyses, Survival Modeling

On multivariate analysis (Table 6), three variables were significantly associated with a poorer patient outcome: urgency of retransplantation (P = .01 and P = .005 for super-urgent and urgent retransplantation, respectively), age (P = .002), and creatinine level (P = .002). PNF as the indication of retransplantation (P = .005), total bilirubin level (P = .02), and level of coagulation factor II (P = .01) were associated with a better prognosis. The Cox model allows calculation of risk score of mortality, taking into account the interactive factors, according to the following formula: Risk Score = 0.04*recipient age + 0.89*logecreatinine − 1.28*PNF + 1.38*super-urgent + 1.27*urgent − 0.23*√(total bilirubin) − 1.38*loge factor II + 0.05*(√(bilirubin) * loge(factor II)), with PNF, super-urgent, and urgent coded as 1 if yes and 0 if no.

Table 6. FINAL PATIENT SURVIVAL MODEL FOR PATIENTS UNDERGOING RETRANSPLANTATION

Figure 4 shows the survival curves obtained for risk scores varying from 1.7 to −0.6 with 5-year patient survival ranging from 15% to 83%. As an example, when a patient aged 20 years is electively retransplanted with a creatinine level of 80 μmol/L, a bilirubin level of 40 μmol/L, and a coagulation factor II level of 80% normal level, his risk score is −1.42 and his probability of survival at 5 years exceeds 80%. When a patient aged 60 years requires a super-urgent retransplantation for a cause other than PNF and has a creatinine level of 300 μmol/L, a bilirubin level of 80 μmol/L, and a coagulation factor II level of 30% normal level, his risk score is 3.63 and his probability of survival at 5 years is less than 10%. Therefore, a risk score can be calculated for a given patient, and an estimated survival probability is given by the survival curves in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Survival curves obtained for risk scores varying from 1.7 to −0.60.

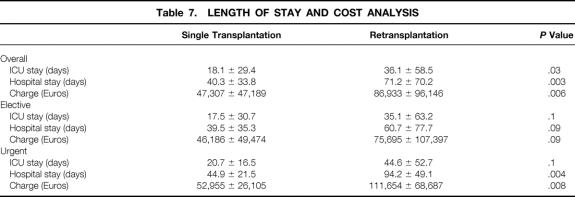

Cost and Length of Stay Analysis

Total hospital length of stay, length of ICU stay, and hospital charges were compared for patients who received a single transplant to those receiving a second transplant. The total average hospital stay (71.2 ± 70.2 vs. 40.3 ± 33.8 days) and ICU stay (36.1 ± 58.5 vs. 18.1 ± 29.4 days) were significantly longer for retransplanted patients compared to those receiving a single transplant (P = .003 and P = .03, respectively). Retransplanted patients incurred significantly higher total charges than did single transplant patients (Euros 86,933 ± 96,146 vs. 47,307 ± 47,189, P = .006). For elective retransplantation, length of stay, ICU stay, and hospital charges were comparable to those of the single transplant group. For urgent retransplantation, hospital charges were significantly higher and length of stay was longer in the retransplantation group, whereas ICU stay was comparable to that of the single transplant group (Table 7).

Table 7. LENGTH OF STAY AND COST ANALYSIS

DISCUSSION

Retransplantation arouses controversy on medical, economic, and ethical grounds: patient and graft survival rates after a second liver transplant are inferior to those after initial grafting, 1,3,4–7,14,19–22 the procedure is more expensive, 4,6,23 and in the context of organ shortage retransplantation inevitably denies organs to first-time recipients. 16,17

Although factors associated with poor organ prognosis in retransplantation have previously been reported, existing studies concentrate on donor and perioperative prognostic criteria. 2,5–7,18–20 In clinical practice these data are not available when a patient is listed for retransplantation, and therefore the objective of this report was to identify factors of prognostic value that would be available when the decision to offer retransplantation is made.

The proportion of retransplanted patients and their outcomes were similar to those of other studies (see Table 1), suggesting broadly comparable patient populations. Analysis of our results suggests the existence of a clear differential outcome between the elective and emergency retransplantation groups. The elective group of retransplantation patients exhibited survival curves indistinguishable from those of the single transplant group. Hence, retransplantation is fully justifiable when performed electively. There was a trend toward a longer hospital stay and higher charges in the retransplantation group, but this did not reach statistical significance, in accordance with D’Alessandro et al. 4 The discrepancy with the ELTR figures showing an inferior overall survival rate following retransplantation compared to the single transplant group may be due to the learning curve effect of retransplantation, as suggested by the correlation between the annual load of transplantation and the results of retransplantation. 24,25

The situation in emergency retransplantation is very different. The results are worse than those obtained for urgent single transplant patients. However, despite its inferior results, hepatic retransplantation cannot be totally abandoned for the ethical and practical reasons that have been detailed previously. 17,19 When all risk factors are present, we believe that retransplantation should be considered with extreme caution, if not contraindicated. For the remaining patients, the decision to proceed to retransplantation or not should be made on a case-by-case basis. In this group the perspective may be to proceed to retransplantation sooner if possible, before progressive deterioration occurs that increases the risks, by using optimal donors and grafts 26 and refinements in retransplantation technique. 27 In this setting there might be a place for living related liver transplantation (LRLT). Indeed, LRLT is programmable and thus allows time to prepare the recipient; it shortens the waiting time, which has been reported as a risk factor for retransplantation;6,18,28 and it provides an optimal graft with the shortest possible ischemia time, another reported risk factor. Few data are available on retransplantation from a living donor. The ELTR counted only 9 retransplantations with a living related donor out of 497 LRLTs performed from 1990 and 2000. 21 Our policy is to propose LRLT for retransplantation when the patient has a worsening condition but still does not have all the identified risk factors; this offers the recipient a reasonable chance of survival and justifies the small but real risk for the donor. As the donor is optimal in the setting of LRLT, the risk of retransplantation as evaluated in the present study may help the surgeon to make a reasonable decision to proceed to this technique for retransplantation.

Analysis of the factors before retransplantation that were associated with 60-day mortality in our series identified a significant correlation with age, serum creatinine level, and ICU-bound recipient status before retransplantation. The adverse influence of each of these factors has been highlighted in previous studies. 1,3,4,6,9,18–20 These risk factors of 60-day mortality were also found to predict long-term survival. This explains why more than 50% of deaths occur during the early postoperative period. When these three risk factors are present, it is difficult to proceed to retransplantation. Several measures may be proposed to improve the results for the remaining patients, including, among others, reducing immunosuppression, which may account for the high infection-related death rate;6,19,28–30 matching the severity of the patient’s condition with the quality of the graft allowed by the allocation of grafts to a center rather than to a given patient;26 and using refinements in retransplantation technique. 27

In summary, our data indicate that long-term survival can be anticipated in nearly 50% of all retransplanted patients. This 50% long-term survival rate is significantly lower than the long-term survival rate following first transplantation. However, retransplantation may still be considered an effective therapy for patients with liver graft failure when we consider that approximately 60% of retransplanted patients are ICU-bound at the time of retransplantation and facing imminent death. Our data confirm the utility of retransplantation in the elective situation. In the emergency setting, retransplantation should be used with discretion and should be avoided in subgroups of patients who have little chance of success. The risk factors we identified confirm the results of other series on this topic and may be of assistance in determining the appropriateness of retransplantation in borderline cases.

Discussion

Prof. H. W. Tilanus: Dear Dr. Azoulay, there are just a few liver transplant centers in the world with such large numbers of liver transplantations that it is worthwhile to draw solid conclusions of their experience in retransplantation. If we look at the experience from the large centers, we can conclude that the 1-year survival after retransplantation varies between 55% and 67% and that is, to my opinion, very acceptable even in the light of donor scarceness and ethical dilemmas.

Predictors for poor outcome were different for early and late retransplantation but essentially focused on infection, artificial ventilation, age, and renal function. The Pittsburgh group saw a significantly better outcome for retransplantation for acute and chronic rejection in the tacrolimus era.

Looking at the common denominators for poor outcome after retransplantation, we can conclude that the whole scene has changed. The percentage of retransplantation has decreased and the survival after retransplantation has increased. In early urgent retransplantation, infection and artificial ventilation are predictors for poor outcome, and in late elective cases, age and renal function of the patient play a dominant role.

I have two questions: one more technical and one more epidemiologic. My first question is: which form of primary transplantation do you prefer regarding possible retransplantation: end-to-end cavocavostomy, or the piggyback variant? My second question is: especially in the light of the increasing indication for liver transplantation of hepatitis C, what is the place of retransplantation for recurrent hepatitis C?

Dr. D. Azoulay: I am not convinced that any type of transplantation may facilitate retransplantation. In view of our experience and of the literature, the incidence of retransplantation for recurrent hepatitis C is comparable to that of retransplantation following transplantation for alcoholic cirrhosis or cholestatic disease.

Prof. R. Margreiter: My question relates to infection: many of these patients were septic, but they have sepsis 2 days before transplantation, so my question is: what is your general attitude towards septic patients?

Dr. D. Azoulay: I think with sepsis there is a very wide range: we have patients with arterial thrombosis and biliary sepsis that is quite controlled because it is a local sepsis, and it is possible when we retransplant to remove the septic foci. On the other side of this wide range of patients, there are patients who have generalized sepsis with positive blood cultures, pulmonary infection, kidney infection. In these patients retransplantation should be contraindicated until sepsis is controlled if possible. In fact, they are contraindicated for retransplantation because this kind of sepsis gives hemodynamic instability and hemodynamic problems that makes the retransplantation impossible.

Prof. H. Bismuth (closing): If I may make a final comment, I think there is today a controversy about the attitudes to allocate the graft. To schematize, there are two attitudes: on the one hand, the “banker” attitude who is looking for benefits; for him, the graft survival comes first. With this attitude, the graft is logically given to a good-risk patient. On the other hand, there is the “doctor” attitude caring for his patient’s survival. With this attitude, the graft is logically given to the sickest patient. I think we have to find a policy between the two, so I think the field is open.

Footnotes

Correspondence: Dr Daniel Azoulay, Centre Hépato-Biliaire, Hôpital Paul Brousse, 94804, Villejuif, France.

E-mail: daniel.azoulay@pbr.ap-hop-paris.fr

Accepted for publication April 2002.

References

- 1.Mora NP, Klintmalm GB, Cofer JB, et al. Results after liver retransplantation (RETx): a comparative study between “elective” vs “nonelective” RETx. Transplant Proc 1990; 22: 1509–1511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morel P, Rilo HLR, Tzakis AG, et al. Liver retransplantation in adults: overall results and determinant factors affecting the outcome. Transplant Proc 1991; 23: 3029–3031. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Powelson JA, Cosimi AB, Lewis WD, et al. Hepatic retransplantation in New England: A regional experience and survival model. Transplantation 1993; 55: 802–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D’Alessandro AM, Ploeg RJ, Knechtle SJ, et al. Retransplantation of the liver: a seven-year experience. Transplantation 1993; 55: 1083–1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong T, Devlin J, Rolando N, et al. Clinical characteristics affecting the outcome of liver retransplantation. Transplantation 1997; 64: 878–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Markmann JF, Markowitz JS, Yersiz H, et al. Long-term survival after retransplantation of the liver. Ann Surg 1997; 226: 408–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoong KF, Gunson BK, Buckels JA, et al. Repeat orthotopic liver transplantation in the 1990s: is it justified? Transplant Int 1998; 11 (Suppl 1): S221–S223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar N, Wall WJ, Grant DR, et al. Liver retransplantation. Transplant Proc 1999; 31: 541–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanchez-Bueno F, Acosta F, Ramirez P, et al. Incidence and survival rate of hepatic retransplantation in a series of 300 orthotopic liver transplants. Transplant Proc 2000; 32: 2671–2672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Facciuto M, Heidt D, Guarrera J, et al. Retransplantation for late liver graft failure: predictors of mortality. Liver Transplant 2000; 6: 174–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaw BW, Gordon RD, Iwatsuki S, et al. Hepatic retransplantation. Transplant Proc 1985; 17: 264. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saito S, Langnas AN, Stratta RJ, et al. Hepatic retransplantation: University of Nebraska Medical Center experience. Clin Transplant 1992; 46: 430–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dawson S, Imagawa DK, Cecka JM, et al. UCLA liver transplantation: analysis of the first 1000 patients. In Terasaki PI, Cecka JM, eds. Clinical transplants 1994. UCLA Tissue Typing Laboratories, 1994:189–195. [PubMed]

- 14.Lemmens HP, Tsiblakis N, Langrehr JM, et al. Comparison of perioperative morbidity following primary liver transplantation and liver retransplantation. Transplant Proc 1993; 25: 1923–1924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tokat Y, Soin A, Saxena R, et al. Posttransplant problems requiring regrafting: an analysis of 72 patients with 96 liver retransplants. Transplant Proc 1995; 27: 1264–1265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evans RW, Mannigan DL, Dong FB, et al. Is retransplantation cost effective? Transplant Proc 1993; 25: 1694–1696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ubel PA, Arnold RM, Caplan AL. Rationing failure: the ethical lessons of the retransplantation of scarce vital organs. JAMA 1993; 270: 2469–2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosen HR, Madden JP, Martin P. A model to predict survival following liver retransplantation. Hepatology 1999; 29: 365–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doyle HR, Marino IR, Jabbour N, et al. Early death or retransplantation in adults after orthotopic liver transplantation. Can outcome be predicted? Transplantation 1994; 57: 1028–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Markmann JF, Gornbein J, Markowitz JS, et al. A simple model to estimate survival after retransplantation of the liver. Transplantation 1999; 67: 422–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.European Liver Transplant Registry. http://www.eltr.org.

- 22.Fangmann J, Ringe B, Hauss J, et al. Hepatic retransplantation: the Hannover experience of two decades. Transplant Proc 1993; 25: 1077–1078. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knechtle S, D’Alessandro A, Reed A, et al. Liver retransplantation: the University of Wisconsin experience. Transplant Proc 1991; 23: 1955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adam R, Cailliez V, Majno P, et al. Normalized intrinsic mortality risk in liver transplantation: European Liver Transplant Registry study. Lancet 2000; 356: 621–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Edwards EB, Roberts JP, McBride MA, et al. The effect of the volume of procedures at transplantation centers on mortality after liver transplantation. N Engl J Med 1999; 341: 2049–2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mirza DF, Gunson BK, Da Silva RF, et al. Policies in Europe on “marginal quality” donor livers. Lancet 1994; 344: 1480–1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lerut JP, Bourlier P, de Ville de Goyet J, et al. Improvement of technique for adult orthotopic liver retransplantation. J Am Coll Surg 1995; 180: 729–732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim WR, Wiesner RH, Poterucha JJ, et al. Hepatic retransplantation in cholestatic liver disease: impact of the interval to retransplantation on survival and resource utilization. Hepatology 1999; 30: 395–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anthuber M, Pratschke E, Jauch KW, et al. Liver retransplantation: indications, frequency, results. Transplant Proc 1992; 24: 1965–1966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shaw BW Jr, Gordon RD, Iwatsuki S, et al. Retransplantation of the liver. Semin Liver Dis 1985; 5: 394–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]