Abstract

Objective:

The aim of the study was to determine pre- and intraoperative risk factors for the development of postoperative delirium among patients undergoing aortic, carotid, and peripheral vascular surgery to predict the risk for postoperative delirium.

Summary Background Data:

Although postoperative delirium after vascular surgery is a frequent complication and is associated with the need for more inpatient hospital care and longer length of hospital stay, little is known about risk factors for delirium in patients undergoing vascular surgery.

Methods:

Pre-, intra-, and postoperative data were prospectively collected, including the first 7 postoperative days with daily follow-up by a surgeon and a psychiatrist of 153 patients undergoing elective vascular surgery. Delirium (Diagnostic and statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV) was diagnosed by the psychiatrist. Multivariate linear logistic regression and a cross validation analysis were performed to find a set of parameters to predict postoperative delirium.

Results:

Sixty patients (39.2%) developed postoperative delirium. The best set of predictors included the absence of supraaortic occlusive disease and hypercholesterinemia, history of a major amputation, age over 65 years, a body size of less than 170 cm, preoperative psychiatric parameters and intraoperative parameters correlated to increased blood loss. The combination of these parameters allows the estimation of an individual patients’ risk for postoperative delirium already at the end of vascular surgery with an overall accuracy of 69.9%.

Conclusions:

Postoperative delirium after vascular surgery is a frequent complication. A model based on pre- and intraoperative somatic and psychiatric risk factors allows prediction of the patient’s risk for developing postoperative delirium.

Postoperative delirium is a common complication after various surgical procedures with an incidence of 0 to 73% (36.8% average).1 It is characterized by an acute onset, a fluctuating course, and an altered level of consciousness and attention (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [DSM] IV2). It is associated with considerable medical complications and increased care resulting in longer length of hospital stay and higher costs. Interestingly, only a few studies focus prospectively on risk factors for the development of postoperative delirium.1,3 These studies mainly investigate cardiothoracic and orthopedic patients.4,5 Only one large trial dealing with patients undergoing abdominal, thoracic, and mostly orthopedic operations included patients undergoing vascular reconstructions.6,7 The authors showed that vascular patients, especially those undergoing aortic procedures, are at a significantly higher risk for developing postoperative delirium. In a retrospective analysis of their data, the same group also showed that intraoperative risk factors (low hemoglobin and hematocrit) are important in the development of postoperative delirium.8 Our study is the second prospective trial designed to identify risk factors for the development of postoperative delirium within a population of vascular patients. The only other trial included patients with critical lower limb ischemia.9 We herein develop a model that allows the prediction of the individual risk for developing postoperative delirium at the end of surgery based on preoperative data and the intraoperative course. This risk quantification aims at an early diagnosis and therapy of postoperative delirium after major vascular surgery.

METHODS

Patients

The study was approved by the Internal Review Board of the School of Medicine of Heinrich–Heine–Universität, Düsseldorf. Patients were studied if the operation time for elective arterial surgery was expected to be than more than 90 minutes. Included were patients with aortic procedures, carotid operations, and those undergoing peripheral bypass surgery. Patients were excluded from the study if they were expected to be on mechanical ventilation for more than 24 hours. In our department, only patients with extended thoracoabdominal aneurysms remain on mechanical ventilation for more than 24 hours routinely.

After written informed consent was obtained, medical data were documented, as well as the primary diagnosis, comorbidity, medication, and preoperative laboratory values. Additionally, patients were examined by an experienced psychiatrist. Depressive symptoms were measured with the Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMD).10 Furthermore, Global Assessment Scale (GAS),11 General Severity Score (ASGS),12 Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS),13 and Mini-Mental-State-Examination (MMSE)14 were used to evaluate psychosocial functioning, general psychopathological symptomatology, and cognitive status. Alcohol abuse was noted if more than 1 drink or bottle of beer (500 cc) was consumed daily.

The anesthesiologist responsible for the patient’s care was not aware of the inclusion of the patient in the study before and during surgery. The documentation of intraoperative parameters was based on the anesthesia protocol. Data analysis was performed immediately after the operation for the time of surgery and anesthesia, course of blood pressure, arterial blood gases, central venous pressure, intraoperative temperature, and the development of laboratory values (eg, hemoglobin).

The general and specific complications, the medication and infusion applied, and the laboratory and hemodynamic data were monitored postoperatively until discharge. In addition to the surgical follow-up postoperatively, patients were seen daily by the psychiatrist from day 1 to day 7. In the case of postoperative delirium patients were seen as long as delirium was detected. The defining criteria of postoperative delirium are described in the DSM IV.2 Delirium was diagnosed if DSM IV criteria were present and the patient reached 12 or more points on the Delirium Rating Scale (DRS).15 The total number of points on the DRS determines the severity of delirium: 12 to 17 = mild delirium, 18 to 28 = moderate delirium, and >28 = severe delirium.

The patients were not included consecutively for lack of psychiatric personnel capacity but were nevertheless representative of the patient population operated at the Vascular Surgery Department of the Heinrich–Heine–University, Düsseldorf with respect to age, comorbidity and surgical procedures.

Stastistical Methods

Univariate analyses (t tests and χ2-test) were performed to differentiate between possible patient factors that were associated with the development of delirium and those not associated with delirium after vascular surgery using the SPSS package (Chicago, IL). Corrections for multiple testing were not performed, for we intended to identify the parameters suitable for multivariate analysis and cross validation.16 Pre- and intraoperative parameters that varied significantly between delirious and nondelirious patients (P < 0.05) in univariate analysis were chosen for stepwise multivariate analysis. For continuous parameters means ± 0.5 × standard deviation were defined as cut-off points.

To obtain an unbiased estimate of the accuracy, a cross-validation procedure was used. We split the data set into 10 parts. We used 9 parts of them as the “training set” to develop a logistic model, which was then tested on the tenth. This procedure was repeated 10 times, each time changing the validation set. A cutoff point of 0.39 (the a priori probability of postoperative delirium in this patient sample) was chosen. We then estimated sensitivity, specificity and accuracy in each of the training and validation sets.

The parameters most often included (at least in 8 of 10 procedures) were selected to form the final linear logistic model using data from all patients. The final model was used to define high and low risk groups for postoperative delirium.

RESULTS

Between September 1997 and December 1998, a total of 219 patients gave written informed consent to participate in the study. Sixty-six (30.1%) were excluded for various reasons (surgery before psychiatric evaluation n = 26, no vascular surgery n = 21, withdrew informed consent n = 11, withdrew consent for surgery n = 2, preoperative resuscitation n = 2, mechanical ventilation for more than seven days n = 2, died on day 1 n = 1, discharged on day 1 n = 1).

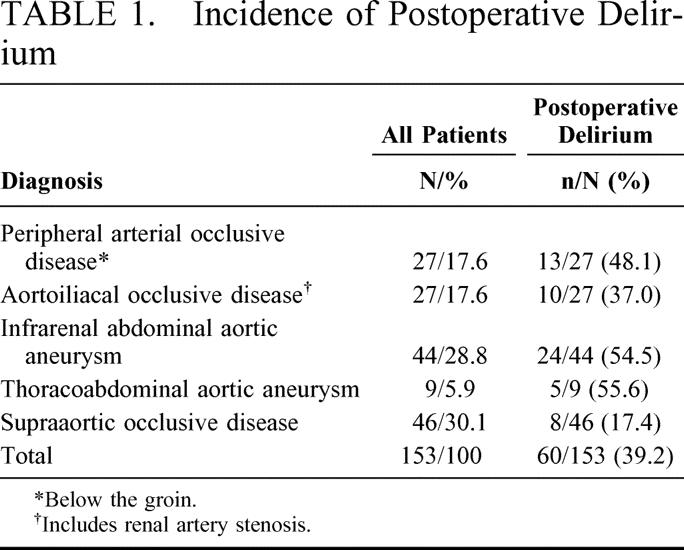

The remaining 153 patients were included in the study. There were 119 men and 34 women. Sixty patients developed postoperative delirium (39.2%), with 36.1% of the men and 50.0% of the women developing postoperative delirium (P = 0.14). The diagnoses leading to surgery and the incidence of postoperative delirium are shown in Table 1. Of 80 patients undergoing aortic surgery, 39 (48.8%) developed postoperative delirium, whereas only 21 patients (28.8%) undergoing nonaortic surgery developed delirium (P = 0.01). Of the 28 patients who had moderate delirium, 22 (78.6%) underwent aortic procedures, and only 6 had (21.4%) nonaortic operations (peripheral bypass n = 3, carotid surgery n = 3).

TABLE 1. Incidence of Postoperative Delirium

Delirious symptoms began in 3 patients on the day of surgery (5%), in 30 (50%) during the first day, in 17 (28.3%) during the second day, in 7 (11.7%) during the third day, and in 2 patients (3.3%) during the fourth day after surgery. Only 1 patient developed delirium several days later (day 6). The average duration of delirium was 3.4 days (1 to 16 days). The more severe forms lasted longer (mild delirium 2.3 days vs. moderate and severe delirium 4.6 days, P = 0.002).

Preoperative Parameters

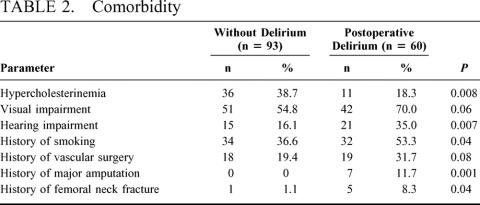

Patients developing postoperative delirium were older than patients not developing postoperative delirium (mean ± SD; 63.7 ± 10.3a vs. 68.3 ± 8.5a, P = 0.005). They were smaller and had the same weight as patients without postoperative delirium (170 ± 9 cm vs. 173 ± 8 cm, P = 0.04; 75.2 ± 15.0 kg vs. 77.1 ± 12.8 kg, P = 0.39). In univariate analysis, a number of concomitant diseases and abnormalities varied significantly between the two groups of patients (Table 2). No differences were found in the following parameters: peripheral occlusive disease, history of psychiatric disease and history of postoperative delirium, actual abuse of alcohol, benzodiazepines, or tobacco. Most of the routine preoperative blood values, including white blood cell count, platelets, routine hepatic enzymes, creatinin and urea, total protein, the coagulation panel excluding antithrombin III (AT III), and serum glucose, sodium, potassium, and calcium, did not demonstrate any difference preoperatively. The only differences in blood values were seen in preoperative hemoglobin, which was lower in the delirious patients (13.7 ± 1.8 g/dL vs. 14.3 ± 1.4 g/dL, P = 0.04) as was AT III (98 ± 15% vs. 106 ± 14.5%, P = 0.02) and C-reactive protein, which was higher in delirious patients (3.4 ± 3.6 mg/dL vs. 1.7 ± 2.3 mg/dL, P = 0.03). No difference was found in the preoperative ASA score (2.9 ± 0.5 vs. 2.8 ± 0.4, P = 0.29).

TABLE 2. Comorbidity

Significant differences were found between the groups in preoperative psychiatric parameters for the following variables: delirious patients showed more depressive symptoms (HAMD, 8.16 ± 5.50 vs. 5.32 ± 5.52, P = 0.002), more general psychiatric symptoms (BPRS, 34.35 ± 10.84 vs. 28.74 ± 9.16, P = 0.002), more psychopathological symptoms before surgery (ASGS, 1.79 ± 1.03 vs. 1.03 ± 1.00, P < 0.001), and decreased psychosocial functioning (GAS, 68.36 ± 14.77 vs. 77.87 ± 15.58, P < 0.001) as well as more cognitive impairments (MMSE, 26.69 ± 2.85 vs. 28.27 ± 1.71, P < 0.001).

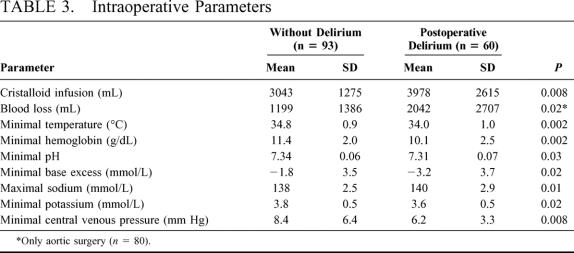

Intraoperative Parameters

Table 3 illustrates the significant differences between patients with and without postoperative delirium in the intraoperative parameters. No differences were found in the time of surgery (with vs. without delirium; 178 ± 118 minutes vs. 148 ± 63 minutes, P = 0.27), time of anesthesia (239 ± 140 minutes vs. 196 ± 72 minutes, P = 0.14), and intraoperative blood pressures, the arterial blood gases, and glucose levels (data not shown). Patients undergoing aortic clamping and developing postoperative delirium tended to have had longer aortic clamping times (41.6 ± 23.4 minutes vs. 33.1 ± 16.9 minutes, P = 0.08). Patients with moderate-to-severe postoperative delirium after aortic surgery had longer clamping times than those with mild delirium (45.6 vs. 37.4 minutes, P = 0.02). No further differences were found with respect to intraoperative medication except for calcium which was more frequently applied in the delirium group (n = 10 vs. n = 3, P = 0.004), and atropine which was given in higher dosage in the delirium group (1.1 mg ± 0.48 (n = 23) vs. 0.85 mg ± 0.51, n = 34, P = 0.03).

TABLE 3. Intraoperative Parameters

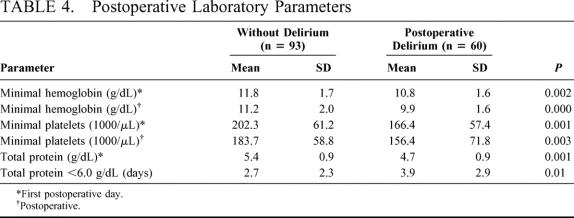

Postoperative Parameters

Table 4 shows the significant differences between the groups in the postoperative laboratory parameters. All other postoperative laboratory values documented, eg, blood gases, did not differ significantly, although patients developing delirium seemed to need more oxygen to maintain satisfactory oxygenation (data not shown). Significantly more patients with delirium needed transfusion of packed red cells (n = 29 vs. 16, P < 0.001) or fresh-frozen plasma (10 vs. 1, P < 0.001).

TABLE 4. Postoperative Laboratory Parameters

Patients with delirium more often removed venous or urinary catheters and drainages (33 vs. 6, P < 0.001) and had catheter site infections more frequently (11 vs. 0, P < 0.001). Furthermore, patients developing delirium had complications more often than those without: reintubation for pulmonary dysfunction (5 vs. 0, P = 0.008), resuscitation (3 vs. 0, P = 0.06), redo surgery (6 vs. 4, P = 0.19), and instable hypertension (30 vs. 28, P = 0.013).

In patients with delirium, intensive or intermediate care unit stay was increased (2.9 ± 2.2 days vs. 2.0 ± 1.5 days, P = 0.01) and the length of postoperative hospital stay was longer (10.9 ± 6.0 days vs. 9.3 ± 8.4 days, P = 0.005).

Cross-Validation, Development, and Testing of the Prediction Model

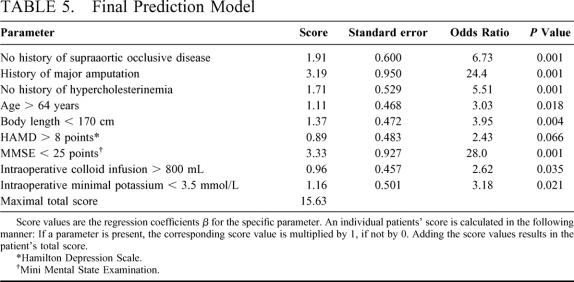

Cross-validation was performed to identify pre- and intraoperative risk factors for postoperative delirium to be included in the multivariate model. Nine parameters, which were identified in at least 8 of the 10 cross-validation procedures, were included in the final model (Table 5). Cross-validation resulted in an average specificity of 78.4%, sensitivity 81.0%, and accuracy 79.5% for the 10 training sets; for the validation sets, it was 71.3% (specificity), 70.2% (sensitivity), and 69.9% (accuracy). Table 5 shows the parameters and the weights. The derived prediction score allows point values ranging from 0 to 15.63.

TABLE 5. Final Prediction Model

Score values are the regression coefficients B for the specific parameter. An individual patients’ score is calculated at the end of surgery in the following manner: If a parameter is present, the corresponding score value is multiplied by 1, if not by 0. Adding these values results in the patients’ total score.

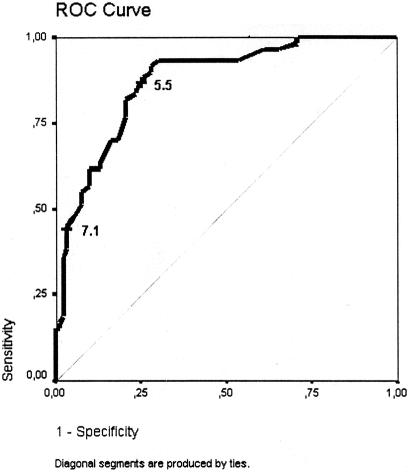

The maximal score of a single patient was 11.67. The higher the total score is, the more likely delirium will develop postoperatively. If a patient has a score of less than 5.5, delirium is unlikely to develop (probability 9.1%). If a patient has a score of more than 7.1 at the end of surgery, then he or she will most likely develop postoperative delirium (probability 89.7%).

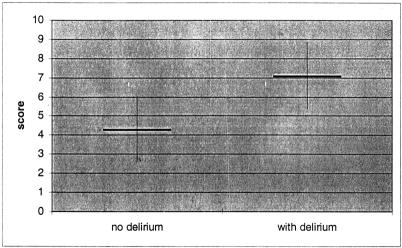

In Figure 1, the corresponding ROC curve is presented. The mean score for patients without delirium is 4.30 ± 1.77 and for patients with delirium it is 7.08 ± 1.79 (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 1. ROC curve for the final prediction model. The cut-off points 5.5 and 7.1 were arbitrarily chosen as examples for high- and low-risk groups (see Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2. Mean score values ± SD of patients with and without postoperative delirium. The maximal score value is 15.63; however, no patient achieved more than 11.67 points.

DISCUSSION

Postoperative delirium is a common complication in most surgical disciplines. Undoubtedly, the patient suffers as a result of his or her condition. Furthermore, the patient is almost unable to cooperate in his or her care. This poses a problem in that it not only increases the nursing workload but may also increase complications, length of stay, and costs.3,17–19 Incidence, diagnosis, risk factors, and treatment of postoperative delirium identified in the literature were subjected to a metanalysis.1 Despite evidence of a high risk for developing delirium (36.8%), reliable studies on risk factors and prediction of postoperative delirium are rare in noncardiac surgery.18–21 Of the studies examining postoperative delirium, only 1 study included vascular patients in a large cohort of postoperative delirium after noncardiac surgery.6–8 Our study is the second prospective trial that included only patients undergoing vascular surgery who are in advanced age and have significant comorbidity. These factors are known to increase the probability of delirium after nonvascular surgery.1 The only other trial with similar results regarding the incidence of delirium was recently published.9 The authors found a 29.1% incidence of delirium in chronic limb ischemia patients, and they identified age over 70 and critical limb ischemia as the only specific risk factors for postoperative delirium.

We can furthermore confirm in our study, which includes a more homogenous group compared to the patient sample of Marcantonio,6,7 that surgical procedure (aortic surgery) and advanced age (>65 years) are risk factors for the development of postoperative delirium. We found that patients with delirium have more complications and need longer intensive or intermediate care unit stay than those without postoperative delirium. Reducing delirium could therefore result in lower complication rates and less inpatient hospital care. A recently published study of a large intervention trial with nonsurgical geriatric patients has shown that improving risk factors associated with delirium development lessens the incidence of postoperative delirium, length of stay, and the incidence of dependent care after discharge.22 Comparable intervention strategies have not been developed for surgical patients because prediction models are not available.

In our patient sample, we identified pre- and intraoperative somatic and psychiatric risk factors for the development of postoperative delirium. Besides hearing disturbances and visual impairment, which are known to increase the rate of delirium after surgery,23 a lower preoperative hemoglobin value, a lower AT III level, a higher preoperative C-reactive protein, a history of major amputation and, interestingly, the lack of hypercholesterinemia in the medical history increase the probability of postoperative delirium. Past studies have failed to identify these latter 4 parameters as potential risk factors for the development of postoperative delirium. The fact that patients with a history of supraaortic occlusive disease are at lower risk for postoperative delirium is explained with the lower incidence of postoperative delirium in this group of patients (17.4%), probably because of the reduced operative trauma compared with aortic surgery.

The results lend support to the only other prospective trial that investigated intraoperative parameters8 besides our study. In that study, the authors also linked somatic risk factors, including the necessary amount of crystalloid volume and the lowest hemoglobin value with the development of delirium. Two additional factors were identified in our study, namely, the lowest intraoperative potassium value and the amount of colloid volume needed intraoperatively, which were also recognized as independent risk factor in cross-validation. These parameters seem to reflect the operative trauma in terms of the total duration of surgery, the blood loss, and volume demand, and the type of surgery.

The multiple and different factors identified as potentially linked to development of postoperative delirium reflect a multifactorial pathogenesis of postoperative delirium, which has not been completely elucidated yet. Even without being clinically apparent, the psychiatric factors according to our preoperative data show that they should be viewed as important risk factors for postoperative delirium. Patients who developed postoperative delirium deviated significantly in the degree of their psychopathological symptomatology before surgery from those patients who did not develop delirium. Patients with postoperative delirium showed higher preoperative depression scores (HAMD) and more severe general psychiatric symptoms (BPRS, ASGS) before surgery. They also demonstrated decreased psychosocial functioning (GAS) and more cognitive impairment (MMSE). The HAMD scores of both groups did not correspond to scores obtained from patients with depression, and the difference between the two groups was subclinical. Preoperative depression, for example, has been significantly linked only by some authors to the development of postoperative delirium in nonvascular surgery.1,23,24,25 Other authors failed to find such an association.6,19 One hypothesis potentially explaining our finding is that serotonin deficiency resulting from tryptophan depletion and phenylalanin elevation is involved in the pathogenesis of postoperative delirium because serotonin is implicated in emotion processing as well as depression.25,26 Patients developing delirium differed from nondelirious patients in that they exhibited some mild psychopathological symptoms (68%), eg, depressed mood and mild insomnia. Their general functioning was however remarkably well. At most, transient symptoms with only minor impairment were found in the nondelirious patients, which is expected after surgery (78%). Cognitive impairments (MMSE) were also greater in the delirious group, even when the scores of both groups were not at all comparable with those in dementia. In line with our findings, preoperative cognitive impairment was linked to the development of postoperative delirium by several authors.7,21,27

Following cross-validation, two variables in particular, preoperative cognitive impairment (MMSE) and the presence of depressive symptoms (HAMD), showed influence on the development of a postoperative delirium. This observation underlines the importance of a psychiatric evaluation before surgery and points to the significance of even subtle psychopathological symptoms.28 Cognitive impairments and depressive symptoms may indicate regional cerebral dysfunctions, which make the organism especially vulnerable to surgical interventions.

Furthermore, the preoperative somatic status with respect to nutrition, hemoglobin level, subclinical infection, and general comorbidity may be contributing factors. Besides the established 50% incidence of delirium for the 2 surgical procedures, aortic and peripheral arterial surgery, a number of complications associated with the intraoperative course documented in infusion volume, hemoglobin levels, transfusion requirements intra- and postoperatively and low platelet counts postoperatively similarly appear to play a significant role in delirium development, a fact not realized in the very few prospective studies on postoperative delirium.1,4,7

However, the current study shows that a multivariate model is necessary to predict postoperative delirium to develop preventive strategies. The prediction score, which is based on a cross-validation analysis, is able to quantify an individual patient’s risk for postoperative delirium at the end of surgery already. The parameters that were found in the present study are totally different than those found in geriatric populations,29 underlining the need for prediction models based on surgical patient data.

Our results should enable any interested clinician to identify patients at risk for delirium and to even quantify this risk if postoperative delirium as a potentially dangerous complication30 is thought of preoperatively. Some of the parameters show very high odds ratios as history of a major amputation and MMSE <25 points, so that patients showing these symptoms must be very carefully managed intra- and postoperatively for their risk for delirium postoperatively is high. For the majority of patients who do not show these 2 symptoms, the prediction model maybe helpful to quantify the patients risk already at the end of surgery. This will enable the physician to have a more alert eye on the patient at risk resulting in earlier diagnosis and treatment of postoperative delirium.

Although the patient group we investigated was not a random sample, which is the major limitation of the study, we investigated a population that was representative for the whole group of patients treated in our department. This does not finally exclude selection bias and future studies will overcome this limitation.

Another limitation of the study is the fact that multiple tests have been used for a rather small patient sample and therefore many of the factors identified as potentially contributing to postoperative delirium may fail to reach statistical significance using corrections for multiple testing.

Clearly, further studies are needed to further clarify and extend the possible causes of delirium. The interesting findings to emerge in our study, such as lack of hypercholesterinemia and preoperative increased C-reactive protein, put into question both the nutritional state and infections in patients before surgery as possible causes of a delirium.

We are optimistic that further evaluation of the proposed prediction model will enable testing and introducing prophylactic intervention beginning at the end of surgery, (e.g. liberal transfusion regimen, increasing intraoperative temperature, preoperative out-patient psychiatric evaluation and intervention etc.) for individuals at risk of developing delirium after vascular and possibly also non-vascular surgery.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors are grateful to Jasmin B. Salloum for editorial help.

Footnotes

Supported by the School of Medicine, University of Düsseldorf to the first and the last author (CH/FK/97).

Reprints: Dr. H. Böhner,Department of General and Vascular Surgery, Lukas-Krankenhaus,Preussen Strasse 84, 41456 Neuss, Germany. E-mail: hboehner@lukasneuss.de.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dyer CB, Ashton CM, Teasdale TA. Postoperative delirium. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:461–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lipowski ZJ. Delirium in the elderly patient. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:578–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herrmann M, Ebert AD, Galazky I, et al. Neurobehavioral outcome prediction after cardiac surgery. Stroke. 2000;31:645–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duppils GS, Wikblad K. Acute consusional states in patients undergoing hip surgery—A prospective observation study. Gerontology. 2000;46:36–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marcantonio ER, Juarez G, Goldmann L, et al. The relationship of postoperative delirium with psychoactive medication. JAMA. 1994;272:1518–1522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marcantonio ER, Goldmann L, Mangione CM, et al. A clinical prediction rule for delirium after elective noncardiac surgery. JAMA. 1994;271:134–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marcantonio ER, Goldman L, Orav EJ, et al. The association of intraoperative factors with the development of postoperative delirium. Am J Med. 1998;105:380–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sasajima Y, Sasajima T, Uchida H, et al. Postoperative delirium in patients with chronic lower limb ischaemia: what are the specific markers? Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2000;20:132–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, Cohen J. The Global Assessment Scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1976;33:766–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooper B. Probleme der Falldefinition und der Fallfindung. [Difficulties in the definition and recognition of cases]. Nervenarzt. 1978;49:437–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Overall JE, Gorham DR. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Rep. 1962;10:799–812. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-Mental-State: a practical method forgrading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trzepacz PT, Baker RW, Greenhouse J. A symptom rating scale for delirium. Psychiatry Res. 1988;23:89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bender R, Lange S. Adjusting for multiple testing—When and how. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:343–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Böhner H, Schneider F, Stierstorfer A, et al. Durchgangssyndrome nach gefäβchirurgischen Operationen—Zwischenergebnisse einer prospektiven Untersuchung [Postoperative delirium following vascular surgery. Comparative results in a prospective study]. Chirurg. 2000;71:215–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Francis J, Martin D, Kapoor W. A prospective study of delirium in hospitalized elderly. JAMA. 1990;263:1097–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gustafson Y, Brannstrom B, Berggren D, et al. A geriatric-anaesthesiological program to reduce acute confusional states in elderly patients treated for femoral neck fractures. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:655–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaneko T, Takahashi S, Naka T, et al. Postoperative delirium following gastrointestinal surgery in elderly patients. Surg Today. 1997;27:107–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams-Russo P, Urquhart BL, Sharrock NE, et al. Post-operative Delirium: predictors and prognosis in elderly orthopedic patients. J Am Ger Soc. 1992;40:759–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inouye S, Bogardus ST, Charpentier PA, et al. A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:669–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Keefe ST, Chonchubhair AN. Postoperative delirium in the elderly. Br J Anaesthesia. 1994;73:673–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levkoff SE, Evans DA, Liptzin B, et al. Delirium. The occurrence and persistence of symptoms among elderly hospitalized patients. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152:334–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uchida K, Aoki T, Ishizuka B. Postoperative delirium and plasma melatonin. Med Hypotheses 1999;53:103–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flacker JM, Lipsitz LA. Neural mechanisms of delirium: current hypotheses and evolving concepts. J Gerontol. 1999;54:239–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Asenbaum S, Zeitlhofer J, Deecke L. Postoperative neuropsychiatrische Störungen und Durchgangssyndrome. [Postoperative neuropsychiatric impairments and delirium]. Internist. 1992;33:425–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schneider F, Böhner H, Habel U, et al. Predictive indicators for the development and the severity of postoperative delirium after vascular surgery. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2002;24:28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Inouye SK, Charpentier PA. Precipitating factors for delirium in hospitalized elderly patients. JAMA. 1996;275:852–857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosen SF, Clagett GP, Valentine RJ, et al. Transient advanced mental impairment: an underappreciated morbidity after aortic surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2002;35:376–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]