Abstract

Objective:

To review the current concepts in the mediastinal staging of nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC), evaluating traditional and modern staging modalities.

Summary Background Data:

Staging of NSCLC includes the assessment of mediastinal lymph nodes. Traditionally, computed tomography (CT) and mediastinoscopy are used. Modern staging modalities include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography (PET), and endoscopic ultrasound with fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA)

Methods:

Literature was searched with PubMed and SUMSearch for original, peer-reviewed, full-length articles. Studies were evaluated on inclusion criteria, sample size, and operating characteristics. Endpoints were accuracy, safety, and applicability of the staging methods.

Results:

CT had moderate sensitivities and specificities. With few exceptions magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) offered no advantages when compared with CT, against higher costs. PET was significantly more accurate than CT. Mediastinoscopy and its variants were widely used as gold standard, although meta-analyses were absent. Percutaneous transthoracic needle biopsy (PTNB) and transbronchial needle biopsy (TBNA) were moderately sensitive and specific. EUS-FNA had high sensitivity and specificity, is a safe and fast procedure, and is cost-effective. EUS-FNA evaluates largely a nonoverlapping mediastinal area compared with mediastinoscopy.

Conclusions:

PET has the highest accuracy in the mediastinal staging of NSCLC, but is not generally used yet. EUS-FNA has the potential to perform mediastinal tissue sampling more accurate than TBNA, PTNB, and mediastinoscopy, with fewer complications and costs. Although promising, EUS-FNA is still experimental. Mediastinoscopy is still considered as gold standard for mediastinal staging of NSCLC.

A structured review of the mediastinal staging of nonsmall cell lung cancer. Methods for imaging and tissue diagnosis are described. Modern modalities like positron emission tomography and endoscopic ultrasound with fine-needle aspiration are discussed and compared with conventional methods like computed tomography and mediastinoscopy.

Nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC) usually metastasizes first to hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes. Subsequently, hematogenous metastasis to distant sites may occur. Because survival is inversely correlated with stage, a meticulous staging procedure is required to determine the treatment and prognosis.1 For staging of NSCLC, the TNM classification has been developed, in which T stands for local tumor extension, N for lymph node metastasis, and M for distant metastasis. The lymph node map by Naruke et al, and its revisions, are often used for the description of the N factor of the TNM classification.1,2 Mediastinal lymph node staging can be divided into imaging and sampling. Computed tomo-graphy (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and positron emission tomography (PET) may be used to image mediastinal lymph nodes.3 Pathologic sampling of suspicious lesions can be performed by mediastinoscopy, mediastinotomy, thoracoscopy, transthoracic fine-needle aspiration, transbronchial fine-needle aspiration, and endoscopic ultrasonography with fine-needle aspiration.4-9 In this article, we will review the current concepts in mediastinal lymph node staging of NSCLC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We searched literature with PubMed and SUMSearch for original, peer-reviewed, full-length articles and meta-analyses in English. We used the following search terms: [lung AND cancer AND staging] and [ct OR computed tomography], [mr OR magnetic resonance], [pet OR positron emission], [mediastin*], [thoracoscop*], [thoracotom*], [endoscop*], [bronchoscop*], [ultraso*], [biopsy], or [punct*]. Further exploration of literature was guided by the reference lists in the articles found with these searches. Studies were evaluated on inclusion criteria, sample size, test, and operating characteristics. Endpoints were accuracy, safety, and applicability of the staging methods.

RESULTS

Computed Tomography

Traditionally, assessment of mediastinal lymph nodes in NSCLC patients is performed with thoracic CT. Two meta-analyses discussed this topic, enclosing 5420 nonoverlapping patients (Table 1). Dales et al included 42 studies (3194 patients) from 1980 to 1988.10 The quality of these studies proved to be variable: criteria for positivity of lymph nodes on CT were not mentioned in 25% of the studies, and the use of intravenous contrast and CT scan time were often not clear. Some authors used a second-generation CT scanner, whereas others used third- or fourth-generation equipment. Unfortunately, there was a tendency toward a higher accuracy with fourth-generation CT (0.83) as compared with third- or second-generation (0.77 and 0.78, respectively). Overall, weighted analysis of the 42 studies resulted in the following operating characteristics: sensitivity 0.83 (95% CI, 0.78–0.87), specificity 0.82 (95% CI, 0.78–0.85), and accuracy 0.80 (95% CI, 0.78–0.84).10 Dwamena et al included 29 studies (2226 patients) from 1990 to 1998.11 Fifteen studies investigated CT in mediastinal NSCLC staging, and 14 studies CT as well as PET. Only research with third- or fourth-generation CT equipment was accepted. No comments were made on the criteria for positivity of mediastinal lymph nodes on CT in the various studies, and studies with lymph nodal and patient based calculations were evaluated together. Sensitivity was 0.60 (95% CI, 0.58–0.62), specificity 0.77 (95% CI, 0.75–0.79), and accuracy 0.75 (95% CI, 0.74–0.76).11 Combining the 2 meta-analyses, the overall accuracy of CT in mediastinal staging of NSCLC seems to be only 0.75 to 0.80, with 20–40% false-negative and 18-23% false-positive results. Apart from these 2 meta-analyses, 3 prospective and 2 retrospective studies with surgical lymph node verification recently showed quite varying operating characteristics, with sensitivities of 0.33–0.75, specificities of 0.66–0.90, and accuracies of 0.64–0.79 (Table 1). Like in the 2 meta-analyses, these authors used different CT protocols, varying population sizes, and either mediastinoscopy, thoracotomy, or both as gold standard. Point of concern is the often incomplete mediastinal lymph node sampling during mediastinoscopy and thoracotomy.12 However, the main problem is the fact that CT only depicts the shape and size of mediastinal lymph nodes, rather than actual tumor involvement. In most articles, a lymph node is considered malignant when its shortest axis is at least 10 mm.3,13-15 This inherently results in moderate operating characteristics, because relation between size and the presence of malignancy is highly variable. Micrometastasis may be present in small nodes, and large nodes may contain only inflammation.8,16 The newest developments in imaging are helical multislice CT and combined multislice CT/PET. Whether the use of these modalities increases accuracy in tumor detection has to be evaluated.

TABLE 1. Computed Tomography in the Mediastinal Staging of Nonsmall Cell Lung Cancer, Surgically Verified

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

The role of MRI in the mediastinal staging of NSCLC is not as well studied as CT. There are no meta-analyses on this subject, and only 2 prospective studies can be retrieved from literature. Webb et al included 170 patients in a study comparing CT and MRI. With a sensitivity of 0.64, a specificity of 0.48, and an accuracy of 0.61, MRI performed almost equally to CT.17 Patterson et al reported better operating characteristics for MRI (sensitivity 0.71, specificity 0.91, accuracy 0.83), but these were obtained in 84 patients of the original 170, after 86 were excluded because of incomplete staging, among other reasons.18 MRI experiences the same disadvantages of the size-related definition of lymph node positivity as CT. The use of contrast-enhanced MRI may improve staging results slightly according to a few small studies.3,19,20 MRI might assess hilar and aortopulmonary window nodes more accurately than CT, because of a better distinction between lymph nodes and blood vessels, although this needs to be confirmed in prospective studies. In case of allergy to CT contrast agent, MRI may be useful.21 With few exceptions, MRI offers no advantages in the mediastinal staging of NSCLC when compared with CT, against higher costs for MRI.

Positron Emission Tomography

Positron emission tomography (PET) using 18F-fluordeoxyglucose as a tracer showed high sensitivities and specificities in the assessment of indeterminate solitary pulmonary nodules.22 Likewise, using metabolic tumor properties instead of size criteria, positivity of mediastinal lymph nodes might approach the actual presence of tumor more closely than CT or MRI. Two meta-analyses on PET were published, both assessing approximately the same studies. Dwamena et al included 14 studies (514 patients) from 1990 to 1998.11 Analysis resulted in a sensitivity of 0.79 (95% CI, 0.76–0.82), a specificity of 0.91 (95% CI, 0.89–0.93), and an accuracy of 0.92 (95% CI, 0.90–0.94). Analysis of the pooled receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of PET and CT indicated that PET was significantly more accurate than CT in identifying mediastinal lymph node metastasis.11 Hellwig et al performed a meta-analysis of 20 studies from 1985 to 1999, enclosing 842 patients. Sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy were 0.88 (95% CI, 0.85–0.91), 0.92 (95% CI, 0.91–0.94), and 0.91 (95% CI, 0.89–0.93), respectively. Again, ROC curves showed that PET was significantly more accurate than CT.23 In both meta-analyses, studies with lymph node and patient-based calculations were evaluated together. Apart from these 2 meta-analyses, 4 recent studies with surgical lymph node verification showed sensitivities of 0.71–0.91, specificities of 0.67–0.94, and accuracies of 0.73–0.92 (Table 2). However, the definition of nodal staging accuracy of PET is not similar in all studies. Pieterman et al and Gupta et al defined lymph node staging as the assessment of N2 and N3 lymph nodes, not including N1 nodes. Dunagan et al defined lymph node staging as the assessment of N1, N2, and N3 lymph nodes. Albes et al, on the contrary, calculated staging accuracy for various nodal groups, being N0 versus N1/2 versus N3, with varying outcomes. Known causes of false-positive PET results are inflammation (tuberculosis, histoplasmosis, sarcoidosis), whereas false-negative results may be caused by carcinoid, bronchoalveolar cell carcinoma, and small lesions (less than 5-7 mm).14,20,24

TABLE 2. 18F-Fluoradeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography in Mediastinal Staging of Nonsmall Cell Lung Cancer, Surgically Verified

In conclusion, PET is very accurate in the mediastinal lymph node staging of NSCLC, and more accurate than CT. With the high negative predictive value, a negative mediastinum on PET leads directly to thoracotomy, without further preoperative mediastinal staging. The lower positive predictive value makes cytologic or histologic confirmation necessary in case of a positive mediastinum on PET.13 The detection of unexpected distant metastasis in about 15% of the cases is another important advantage of PET.13

Whether PET can be replaced by cheaper alternatives is an ongoing matter of debate and research. Single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) is cheaper, but that does not compensate for its lower accuracy.25-27

Surgical Staging: Mediastinoscopy, Mediastinotomy, and Video-Assisted Thoracoscopy

Several variants of mediastinoscopy can be distinguished. Cervical mediastinoscopy (CM) can assess lymph node levels 2 left and right, 4 left and right, and 7. It is often considered as gold standard for the mediastinal staging of NSCLC.28 Debate is ongoing about how ‘gold’ this standard is.29 There are only a few partly retrospective studies with varying designs and extents of lymph node sampling (Table 3). Patterson et al compared MRI, CT and CM in a preoperative setting. The number of sampled mediastinal lymph node levels was very low (levels 2 right, 4 right, and 7 only), and extended cervical mediastinoscopy was also applied for left upper lobe lesions.18 De Leyn et al assessed the role of CM in patients with previous N0 on CT, a highly selected population.30 Porte et al had a very low sampling rate of 1.6 lymph node level per examination.31 Overall, a very moderate sensitivity of 0.44–0.92 was reported. Specificities and positive predictive values of 1.00 are the result of the study designs, and refer to what has been found during CM and not to what should have been found at the different lymph node levels. Patients with positive N2 lymph nodes32,33 at cervical mediastinoscopy have a different prognosis compared with patients with negative N2 lymph nodes, even if the latter patients have positive N2 lymph nodes at thoracotomy.34,35

TABLE 3. Cervical Mediastinoscopy in the Mediastinal Staging of Nonsmall Cell Lung Cancer, Surgically Verified

Cervical mediastinoscopy can be extended (ECM) to reach lymph node levels 5 and 6.36 Only 2 peer-reviewed studies on ECM can be found. Freixinet Gilart et al prospectively studied 93 patients with NSCLC and aortopulmonary window nodes on CT. Sensitivity, accuracy, and negative predictive value were 0.81, 0.94, and 0.91, respectively.36 Ginsberg et al performed a prospective analysis of 100 ECM procedures in patients with left upper lobe NSCLC. They reported a sensitivity, accuracy, and negative predictive value of 0.69, 0.91, and 0.89, respectively. The authors indicated that ECM must be performed in addition to CM, but many surgeons do not follow this recommendation.37 Anterior mediastinotomy (AM) is suitable for lesions in the anterior and superior mediastinum or hili, when CM is contraindicated, or in case of a left upper lobe tumor.9,38 Barendregt et al retrospectively studied AM in 37 patients with left upper lobe tumors. In 16 patients (43%), a mediastinal lymph node or tumor was seen or palpated and biopsied. One true-positive and 4 false-negative findings resulted in a sensitivity, accuracy, and negative predictive value of only 0.20, 0.89, and 0.89, respectively.38 Jiao et al retrospectively assessed the use of CM plus AM. Sensitivity, accuracy, and negative predictive value of 0.43, 0.85, and 0.83, respectively, were reported.39 Video-assisted thoracoscopy (VATS) can image an entire hemithorax plus almost every mediastinal lymph node level, with minimal incision and morbidity, but generally only one-sided.4,40 Champion and McKernan studied this technique in 17 patients before thoracotomy. They sampled mediastinal lymph node levels 2, 4, 5, and 7. VATS performed equally to thoracotomy.5 The use of these surgical procedures is more dictated by tradition than by well-designed studies. Only CM has a firm place in the work-up of patients with NSCLC. CM, ECM, AM, and VATS are generally performed under general anesthesia, some surgeons perform CM in day care setting.4 There are (relative) contraindications, including previous mediastinoscopy, previous local surgery or irradiation, aortic aneurysm, superior vena cava obstruction, and inability to withstand single-lung ventilation (VATS only).40 The complication rate of CM is approximately 2.5%, including paresis of the left laryngeal recurrent nerve, hemorrhage, pneumothorax, pneumonia, injury to the azygos vein, perforation of the esophagus, and mediastinitis.31,40 The complication rate of AM is 6.7–9%, with 1% mortality. The complication rate of VATS may be as high as 14%, with hemothorax, air embolism, or lacerations to the lungs or blood vessels. Emergency thoracotomy is required in 1-3%, and the mortality rate is approximately 4.5%.40

Percutaneous Transthoracic Needle Biopsy

Percutaneous transthoracic needle biopsy (PTNB) can be used for the mediastinal staging of NSCLC. Meta-analyses on this subject are not available. CT guidance is preferred, because the lesions tend to be small and adjacent to major blood vessels. PTNB usually permits puncture of mediastinal lymph nodes larger than 1.5 cm.41 The role of PTNB for the diagnosis of lung cancer has been described in 3 recent reviews. However, no operating characteristics were provided for mediastinal NSCLC staging.42-44 Akamatsu et al prospectively studied PTNB in the assessment of enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes (N2) on CT in patients with NSCLC. Only lymph node levels 4 right, 6, and 7 were punctured. Overall sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy were 0.88, 1.00, and 0.89, respectively. Postbiopsy pneumothorax occurred in 22% of the procedures.6 Protopapas and Westcott retrospectively analyzed PTNB in patients with various carcinomas and N2 mediastinal disease on CT. Sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy were 0.98, 1.00, and 0.98, respectively. Postbiopsy pneumothorax was reported in 34%, and 14% required a chest tube.45 Pneumothorax is the most frequent complication (5–61%), especially in patients with COPD, requiring chest tube insertion in 1.6–17% of the patients.43,44,46 Other complications, such as hemothorax, hemoptysis, air embolism, or empyema are rare.42 Implantation of tumor cells at the punction site is rare, reported to be approximately 1 in 4000 procedures.47-49 Contraindications for PTNB are COPD, poor lung function, diffuse pulmonary disease, clotting disorders, pulmonary hypertension, contralateral pneumonectomy, and arteriovenous malformation.41-43

Transbronchial Fine-Needle Aspiration

Transbronchial fine-needle aspiration (TBNA) for the mediastinal staging of NSCLC has been described in literature, albeit not as meta-analysis. In a prospective Turkish study, the authors assessed mediastinal, hilar, and intrapulmonary lymph nodes by TBNA in 138 patients, with a sensitivity of 0.70–0.74.7 A sensitivity of 0.60 was reported by Rong and Cui, after prospective analysis of 39 patients.50 Schenk et al used TBNA to assess enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes in 88 patients after tracheal intubation, just before surgical staging. They reported a sensitivity of 0.50, a specificity of 0.96, and an accuracy of 0.78.51 These 3 prospective studies showed a range of sensitivities for TBNA, although it was applied in patients with established mediastinal lymph node (N2) enlargement on CT. Similar results were reported in 2 retrospective studies, with sensitivities of 0.36-0.71 and specificities of 0.92-1.00.52,53 Only lymph nodes next to the large airways can be reached, mainly on levels 4 right, 4 left, and 7.40 CT guidance increases the sensitivity of TBNA, as may endobronchial ultrasonography.50,54,55 Both cytologic and histologic specimens can be obtained, depending on the needle used.7 The complication rate is 2-5%, including hemorrhage and pneumothorax.7,54,56 In conclusion, TBNA is considered as safe, minimally invasive, and relatively inexpensive, although its yield is moderate.52,57

Endoscopic Ultrasonography

For approximately 2 decades, endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) has been used for the diagnosis and staging of gastrointestinal malignancies, with high accuracy and superior results compared with CT, MRI, angiography, and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.58-61 Visual assessment of mediastinal lymph nodes by EUS gave for various observers sensitivities of 0.54–0.75, specificities of 0.71–0.98, positive predictive values of 0.46–0.77, and negative predictive values of 0.85–0.93, in a total number of 262 patients (Table 4, marked with *). All were histologically verified by either mediastinoscopy or lymph node dissection at thoracotomy. The use of only visual aspects of lymph nodes for the definition of malignancy results in moderate operating characteristics. These studies varied widely with regard to the number of examined mediastinal lymph node levels, visual criteria for malignancy, and patient population characteristics. Compared with CT, the detection rate of malignant lymph nodes is higher with EUS, with less false-positive results.8,62 EUS can assess mediastinal lymph nodes at most levels, particularly at levels 4 left, 5, 7, 8, and 9, as well as metastasis in the left adrenal gland.8,62-68 Levels 1, 2, 3, and 4 right are not always assessable, because of interference by air in the larger airways. When enlarged, however, detection is more easy.66,69-71 Properties of lymph nodes indicating possible malignancy are a hypoechoic core, sharp edges, round shape, and a long axis diameter exceeding 10 mm.72-74 Signs of benignancy are a hyperechoic core (fat), central calcification (old granulomatous disease), ill-defined edges, a long and narrow shape, and a long axis diameter up to 10 mm.70,73,75,76 Histoplasmosis, sarcoidosis, and anthracosilicosis may cause false-positive EUS images.64,70,77,78 Diagnostic accuracy of EUS improves substantially when fine-needle aspiration (FNA) of the localized lymph nodes is added. Fourteen studies with a total number of 877 patients reported sensitivities of 0.81–0.97, and specificities of 0.83–1.00 (Table 4). Again, variable designs and study qualities can be observed. Some studies assessed EUS-FNA for the staging of patients with proven NSCLC, whereas other studies assessed the accuracy of EUS-FNA in the diagnosis of mediastinal lymph nodes without prior diagnosis.69,71,79 Geographical circumstances varied, with subsequent different exposures to histoplasmosis and anthracosilicosis.8,78 False-negative results may have been introduced by the sometimes poor lymph node sampling during EUS-FNA (sampling only the most suspicious nodes), and some of the studies are clearly underpowered.76,79,80 Many outcomes were supported by clinical instead of surgical follow-up.68,69,71,81,82 Despite these drawbacks, the clinical impact of EUS-FNA is illustrated by a change in the management of NSCLC after EUS-FNA in 66% of the patients, or cancellation of 68% and 49% of the scheduled mediastinoscopies and thoracotomies, respectively.78,83 According to Hunerbein et al, EUS-FNA made an unexpected diagnosis in 30% of the procedures.84 In 2 studies with decision-analysis models, EUS-FNA was shown to be less expensive compared with mediastinoscopy for the assessment of the entire mediastinum or for subcarinal lymph nodes only.63,85

TABLE 4. Endoscopic Ultrasound with Fine-Needle Aspiration in the Mediastinal Staging of Nonsmall Cell Lung Cancer, Surgically Verified

Barawi et al prospectively studied the incidence of complications associated with EUS-FNA. In 842 mediastinal EUS-FNA procedures, 1 infection, 2 hemorrhages, and 1 inexplicable transient hypotension were reported.86 EUS-FNA is contraindicated in patients with a Zenker’s diverticulum or bleeding tendency.70,71,87 FNA of a cystic mediastinal lesion should be avoided, or when necessary be preceded by prophylactic antibiotics.69,72,76 This applies also to immune compromised patients.73,79

In conclusion, EUS-FNA seems to be very accurate, safe, and economic in the assessment of mediastinal lymph nodes in patients with NSCLC. More prospective randomized studies are needed, however, especially on the use of EUS-FNA in combination with PET to elucidate its place in the diagnostic work-up of NSCLC

DISCUSSION

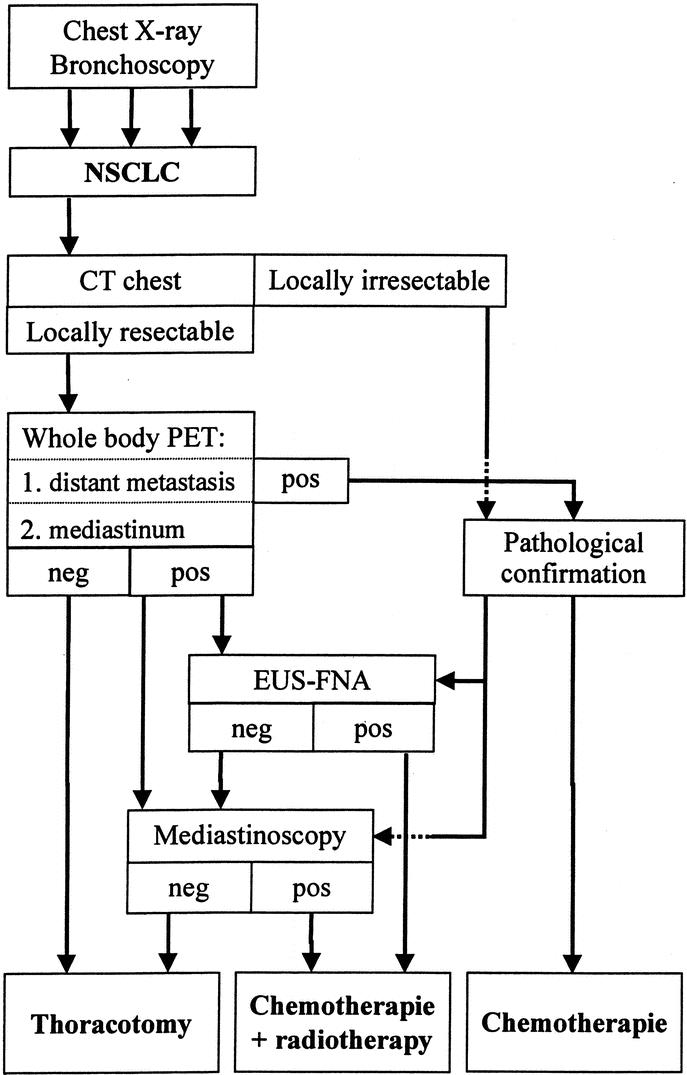

Proper staging of the mediastinum in NSCLC is a difficult task. Staging is, however, required for optimal treatment in relation to the patient’s tumor stage. Minimal clinical staging recommendations were outlined in consensus meetings.88-90 PET was partly included in these guidelines, whereas EUS-FNA was not. New imaging and diagnostic tests are changing the accuracy of the overall outcome, leading to stage migration. One of the problems is how to integrate new tests, such as PET and EUS-FNA, in the existing diagnostic algorithms. In the current article, a mediastinal staging algorithm was constructed incorporating these new techniques (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1. Algorithm for the staging and treatment of NSCLC.

When the diagnosis of NSCLC has been established or strongly suspected after thoracic x-ray and/or bronchoscopy, CT is performed to assess the exact anatomic localization of the lesions and their local resectability. If the tumor seems locally resectable, PET is performed to eliminate the presence of unsuspected distant metastases. PET can easily demonstrate distant hotspots, but these need pathologic confirmation. When distant metastases are absent, a PET-negative mediastinum directly leads to thoracotomy. PET has the highest accuracy for mediastinal staging of NSCLC. Mediastinal hotspots also need tissue confirmation because the positive predictive value is only 0.74. PET is not suitable for the detection of brain metastasis due to high glucose uptake in normal brain tissue. Contrast-enhanced CT or MRI performs much better in this situation. Whether CT or MRI of the brain should be part of routine NSCLC staging is an ongoing matter of debate.91-93 It seems reasonable to refrain from CT/MRI imaging of the brain in early stage (T1/2, N0) NSCLC patients without clinical evidence for brain metastasis.92

Mediastinal lymph node sampling can be performed with different methods. Mediastinal NSCLC staging will discriminate between N2 or N3 lymph nodes. Imaging techniques can poorly assess N1 lymph nodes (hilar or segmental). However, this seems not to be a major drawback, because N1 assessment will easily be resected. Only in case of poor pulmonary function N1 lymph nodes must be carefully assessed in advance, because segmentectomy may then be the only option to resect the primary tumor, thus extending life expectancy. Cervical mediastinoscopy is used in case of a hotspot on level 1, 2, 4 right, or 6 (extended mediastinoscopy), and after negative or unsuccessful EUS-FNA. EUS-FNA is the preferred method if a PET hotspot is located on Naruke level 4 left, 5, 7, 8, or 9. Whether EUS-FNA can partly replace cervical mediastinoscopy is still under research. Preliminary results show that the introduction of EUS-FNA in our clinic in this setting reduces the number of mediastinoscopies with 70%.94 Other mediastinal staging methods are TBNA or PTNB, which are used in specific circumstances only, where EUS-FNA and mediastinoscopy failed or could not be applied. If distant and mediastinal malignancy cannot be demonstrated, thoracotomy will be performed. In case of equivocal staging results, patients should be treated as having no metastasis. This is clinically important when it is impossible to prove malignancy in a lesion that has already a low pretest probability of being malignant. Note that when a patient has a poor performance score or limited functional capacities, this may be a reason to refrain from specific staging procedures.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Supported by The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development through research grant 945-10-003.

Footnotes

Reprints: H. Kramer, MD, University Hospital Groningen, Department of Pulmonary Diseases, PO Box 30 001, 9700 RB Groningen, The Netherlands. E-mail: h.kramer@int.azg.nl.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mountain CF. The international system for staging lung cancer. Semin Surg Oncol. 2000;18:106–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mountain CF, Dresler CM. Regional lymph node classification for lung cancer staging. Chest. 1997;111:1718–1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kernstine KH, Stanford W, Mullan BF, et al. PET, CT, and MRI with Combidex for mediastinal staging in non-small cell lung carcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;68:1022–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mentzer SJ, Swanson SJ, DeCamp MM, et al. Mediastinoscopy, thoracoscopy, and video-assisted thoracic surgery in the diagnosis and staging of lung cancer. Chest. 1997;112:239S–241S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Champion JK, McKernan JB. Comparison of minimally invasive thoracoscopy versus open thoracotomy for staging lung cancer. Int Surg. 1996;81:235–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akamatsu H, Terashima M, Koike T, et al. Staging of primary lung cancer by computed tomography-guided percutaneous needle cytology of mediastinal lymph nodes. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;62:352–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bilaceroglu S, Cagiotariotaciota U, Gunel O, et al. Comparison of rigid and flexible transbronchial needle aspiration in the staging of bronchogenic carcinoma. Respiration. 1998;65:441–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gress FG, Savides TJ, Sandler A, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography, fine-needle aspiration biopsy guided by endoscopic ultrasonography, and computed tomography in the preoperative staging of non-small-cell lung cancer: a comparison study. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:604–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McNeill TM, Chamberlain JM. Diagnostic anterior mediastinotomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 1966;2:532–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dales RE, Stark RM, Raman S. Computed tomography to stage lung cancer. Approaching a controversy using meta-analysis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;141:1096–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dwamena BA, Sonnad SS, Angobaldo JO, et al. Metastases from non-small cell lung cancer: mediastinal staging in the 1990s–meta-analytic comparison of PET and CT. Radiology. 1999;213:530–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Staples CA, Muller NL, Miller RR, et al. Mediastinal nodes in bronchogenic carcinoma: comparison between CT and mediastinoscopy. Radiology. 1988;167:367–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pieterman RM, Van Putten JWG, Meuzelaar JJ, et al. Preoperative staging of non-small-cell lung cancer with positron-emission tomography. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:254–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunagan D, Chin R, McCain TW, et al. Staging by positron emission tomography predicts survival in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Chest. 2001;119:333–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamiyoshihara M, Kawashima O, Ishikawa S, et al. Mediastinal lymph node evaluation by computed tomographic scan in lung cancer. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino). 2001;42:119–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ikezoe J, Kadowaki K, Morimoto S, et al. Mediastinal lymph node metastases from nonsmall cell bronchogenic carcinoma: reevaluation with CT. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1990;14:340–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Webb WR, Gatsonis C, Zerhouni EA, et al. CT and MR imaging in staging non-small cell bronchogenic carcinoma: report of the Radiologic Diagnostic Oncology Group. Radiology. 1991;178:705–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patterson GA, Ginsberg RJ, Poon PY, et al. A prospective evaluation of magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography, and mediastinoscopy in the preoperative assessment of mediastinal node status in bronchogenic carcinoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1987;94:679–684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laissy JP, Gay-Depassier P, Soyer P, et al. Enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes in bronchogenic carcinoma: assessment with dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging. Work in progress. Radiology. 1994;191:263–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haberkorn U, Schoenberg SO. Imaging of lung cancer with CT, MRT and PET. Lung Cancer 2001;34(Suppl 3):13–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grover FL. The role of CT and MRI in staging of the mediastinum. Chest. 1994;106:391S–396S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gould MK, Maclean CC, Kuschner WG, et al. Accuracy of positron emission tomography for diagnosis of pulmonary nodules and mass lesions: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2001;285:914–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hellwig D, Ukena D, Paulsen F, et al. [Metaanalysis of the efficacy of positron emission tomography with F-18- fluorodeoxyglucose]. Pneumologie. 2001;55:367–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gupta NC, Tamim WJ, Graeber GM, et al. Mediastinal lymph node sampling following positron emission tomography with fluorodeoxyglucose imaging in lung cancer staging. Chest. 2001;120:521–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higashi K, Nishikawa T, Seki H, et al. Comparison of fluorine-18-FDG PET and thallium-201 SPECT in evaluation of lung cancer. J Nucl Med. 1998;39:9–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tatsumi M, Yutani K, Nishimura T. Evaluation of lung cancer by 99mTc-tetrofosmin SPECT: comparison with [18F]FDG-PET. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2000;24:574–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higashi K, Ueda Y, Sakuma T, et al. Comparison of [(18)F]FDG PET and. (201)Tl SPECT in evaluation of pulmonary nodules. J Nucl Med. 2001;42:1489–1496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoffmann H. Invasive staging of lung cancer by mediastinoscopy and video-assisted thoracoscopy. Lung Cancer. 2001;34(Suppl 3):3–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Margaritora S, Cesario A, Galetta D, et al. Mediastinoscopy as a standardised procedure for mediastinal lymph-node staging in non-small cell carcinoma. Do we have to accept the compromise? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2001;20:652–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Leyn PR, Vansteenkiste J, Cuypers P, et al. Role of cervical mediastinoscopy in staging of non-small cell lung cancer without enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes on CT scan. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1997;12:706–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Porte H, Roumilhac D, Eraldi L, et al. The role of mediastinoscopy in the diagnosis of mediastinal lymphadenopathy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1998;13:196–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldstraw P, Mannam GC, Kaplan DK, et al. Surgical management of non-small-cell lung cancer with ipsilateral mediastinal node metastasis (N2 disease). J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;107:19–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vansteenkiste JF, De Leyn PR, Deneffe GJ, et al. Survival and prognostic factors in resected N2 non-small cell lung cancer: a study of 140 cases. Leuven Lung Cancer Group. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;63:1441–1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mountain CF. Surgery for stage IIIa-N2 non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer. 1994;73:2589–2598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pearson FG, DeLarue NC, Ilves R, et al. Significance of positive superior mediastinal nodes identified at mediastinoscopy in patients with resectable cancer of the lung. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1982;83:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Freixinet Gilart J, Garcia PG, De Castro FR, et al. Extended cervical mediastinoscopy in the staging of bronchogenic carcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;70:1641–1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ginsberg RJ, Rice TW, Goldberg M, et al. Extended cervical mediastinoscopy. A single staging procedure for bronchogenic carcinoma of the left upper lobe. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1987;94:673–678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barendregt WB, Deleu HW, Joosten HJ, et al. The value of parasternal mediastinoscopy in staging bronchial carcinoma. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1995;9:655–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiao X, Magistrelli P, Goldstraw P. The value of cervical mediastinoscopy combined with anterior mediastinotomy in the peroperative evaluation of bronchogenic carcinoma of the left upper lobe. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1997;11:450–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bogot NR, Shaham D. Semi-invasive and invasive procedures for the diagnosis and staging of lung cancer. II. Bronchoscopic and surgical procedures. Radiol Clin North Am. 2000;38:535–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gardner D, Van Sonnenberg E, D’Agostino HB, et al. CT-guided transthoracic needle biopsy. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1991;14:17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shaham D. Semi-invasive and invasive procedures for the diagnosis and staging of lung cancer I. Percutaneous transthoracic needle biopsy. Radiol Clin North Am. 2000;38:525–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salazar AM, Westcott JL. The role of transthoracic needle biopsy for the diagnosis and staging of lung cancer. Clin Chest Med. 1993;14:99–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perlmutt LM, Johnston WW, Dunnick NR. Percutaneous transthoracic needle aspiration: a review. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1989;152:451–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Protopapas Z, Westcott JL. Transthoracic needle biopsy of mediastinal lymph nodes for staging lung and other cancers. Radiology. 1996;199:489–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fish GD, Stanley JH, Miller KS, et al. Postbiopsy pneumothorax: estimating the risk by chest radiography and pulmonary function tests. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1988;150:71–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sawabata N, Ohta M, Maeda H. Fine-needle aspiration cytologic technique for lung cancer has a high potential of malignant cell spread through the tract. Chest. 2000;118:936–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bedirhan MA, Turna A. Fine-needle aspiration and tumor seeding. Chest. 2001;120:1037–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nordenström B, Bjork VO. Dissemination of cancer cells by needle biopsy of lung. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1973;65:671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rong F, Cui B. CT scan directed transbronchial needle aspiration biopsy for mediastinal nodes. Chest. 1998;114:36–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schenk DA, Bower JH, Bryan CL, et al. Transbronchial needle aspiration staging of bronchogenic carcinoma. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1986;134:146–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Disdier C, Varela G, Sánchez de Cos J, et al. [Usefulness of transbronchial punction and mediastinoscopy in mediastinal nodal staging of non-microcytic bronchogenic carcinoma. Preliminary study]. Arch Bronconeumol. 1998;34:237–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Patelli M, Agli LL, Poletti V, et al. Role of fiberscopic transbronchial needle aspiration in the staging of N2 disease due to non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73:407–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shannon JJ, Bude RO, Orens JB, et al. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided needle aspiration of mediastinal adenopathy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153:1424–1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Okamoto H, Watanabe K, Nagatomo A, et al. Endobronchial ultrasonography for mediastinal and hilar lymph node metastases of lung cancer. Chest. 2002;121:1498–1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Salathe M, Soler M, Bolliger CT, et al. Transbronchial needle aspiration in routine fiberoptic bronchoscopy. Respiration. 1992;59:5–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Harrow EM, Oldenburg FA Jr., Lingenfelter MS, et al. Transbronchial needle aspiration in clinical practice. A five-year experience. Chest. 1989;96:1268–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tio TL, Coene PP, Hartog Jager FC, et al. Preoperative TNM classification of esophageal carcinoma by endosonography. Hepatogastroenterology. 1990;37:376–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ziegler K, Sanft C, Zimmer T, et al. Comparison of computed tomography, endosonography, and intraoperative assessment in TN staging of gastric carcinoma. Gut. 1993;34:604–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cahn M, Chang KJ, Nguyen P, et al. Impact of endoscopic ultrasound with fine-needle aspiration on the surgical management of pancreatic cancer. Am J Surg. 1996;172:470–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tio TL, Coene PP, Van Delden OM, et al. Colorectal carcinoma: preoperative TNM classification with endosonography. Radiology. 1991;179:165–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Laudanski J, Kozlowski M, Niklinski J, et al. The preoperative study of mediastinal lymph nodes metastasis in lung cancer by endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) and helical computed tomography (CT). Lung Cancer. 2001;34(Suppl 2):S123–S126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Aabakken L, Silvestri GA, Hawes RH, et al. Cost-efficacy of endoscopic ultrasonography with fine-needle aspiration vs. mediastinotomy in patients with lung cancer and suspected mediastinal adenopathyt. Endoscopy. 1999;31:707–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mishra G, Sahai AV, Penman ID, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography with fine-needle aspiration: an accurate and simple diagnostic modality for sarcoidosis. Endoscopy. 1999;31:377–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kondo D, Imaizumi M, Abe T, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound examination for mediastinal lymph node metastases of lung cancer. Chest. 1990;98:586–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Serna DL, Aryan HE, Chang KJ, et al. An early comparison between endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration and mediastinoscopy for diagnosis of mediastinal malignancy. Am Surg. 1998;64:1014–1018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lee N, Inoue K, Yamamoto R, et al. Patterns of internal echoes in lymph nodes in the diagnosis of lung cancer metastasis. World J Surg. 1992;16:986–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chang KJ, Erickson RA, Nguyen P. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration of the left adrenal gland. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:568–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fritscher-Ravens A, Petrasch S, Reinacher-Schick A, et al. Diagnostic value of endoscopic ultrasonography-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology of mediastinal masses in patients with intrapulmonary lesions and nondiagnostic bronchoscopy. Respiration. 1999;66:150–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schuder G, Isringhaus H, Kubale B, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography of the mediastinum in the diagnosis of bronchial carcinoma. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1991;39:299–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fritscher-Ravens A, Soehendra N, Schirrow L, et al. Role of transesophageal endosonography-guided fine-needle aspiration in the diagnosis of lung cancer. Chest. 2000;117:339–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Williams DB, Sahai AV, Aabakken L, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration biopsy: a large single centre experience. Gut. 1999;44:720–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wiersema MJ, Vilmann P, Giovannini M, et al. Endosonography-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy: diagnostic accuracy and complication assessment. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1087–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Faigel DO. EUS in patients with benign and malignant lymphadenopathy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:593–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hawes RH, Gress FG, Kesler KA, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound versus computed tomography in the evaluation of the mediastinum in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Endoscopy. 1994;26:784–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wiersema MJ, Vazquez-Sequeiros E, Wiersema LM. Evaluation of mediastinal lymphadenopathy with endoscopic US-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy. Radiology. 2001;219:252–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wiersema MJ, Chak A, Wiersema LM. Mediastinal histoplasmosis: evaluation with endosonography and endoscopic fine-needle aspiration biopsy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:78–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ikenberry SO, Gress FG, Savides TJ, et al. Fine-needle aspiration of posterior mediastinal lesions guided by radial scanning endosonography. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;43:605–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fritscher-Ravens A, Sriram PV, Bobrowski C, et al. Mediastinal lymphadenopathy in patients with or without previous malignancy: EUS-FNA-based differential cytodiagnosis in 153 patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2278–2284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Silvestri GA, Hoffman BJ, Bhutani MS, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound with fine-needle aspiration in the diagnosis and staging of lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;61:1441–1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Giovannini M, Seitz JF, Monges G, et al. Fine-needle aspiration cytology guided by endoscopic ultrasonography: results in 141 patients. Endoscopy. 1995;27:171–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pedersen BH, Vilmann P, Folke K, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography and real-time guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy of solid lesions of the mediastinum suspected of malignancy. Chest. 1996;110:539–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Larsen SS, Krasnik M, Vilmann P, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound guided biopsy of mediastinal lesions has a major impact on patient management. Thorax. 2002;57:98–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hunerbein M, Ghadimi BM, Haensch W, et al. Transesophageal biopsy of mediastinal and pulmonary tumors by means of endoscopic ultrasound guidance. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;116:554–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Harewood GC, Wiersema MJ, Edell ES, et al. Cost-minimization analysis of alternative diagnostic approaches in a modeled patient with non-small cell lung cancer and subcarinal lymphadenopathy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77:155–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Barawi M, Gottlieb K, Cunha B, et al. A prospective evaluation of the incidence of bacteremia associated with EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:189–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lightdale CJ. Indications, contraindications, and complications of endoscopic ultrasonography. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;43:S15–S19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.ESMO Minimum Clinical Recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Ann Oncol. 2001;12:1049–1050. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 89.Feld R, Abratt R, Graziano S, et al. Pretreatment minimal staging and prognostic factors for non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 1997;17(Suppl 1):S3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Goldstraw P, Rocmans P, Ball D, et al. Pretreatment minimal staging for non-small cell lung cancer: an updated consensus report. Lung Cancer. 1994;11(Suppl 3):S1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Earnest F, Ryu JH, Miller GM, et al. Suspected non-small cell lung cancer: incidence of occult brain and skeletal metastases and effectiveness of imaging for detection–pilot study. Radiology. 1999;211:137–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tanaka K, Kubota K, Kodama T, et al. Extrathoracic staging is not necessary for non-small-cell lung cancer with clinical stage T1-2 N0. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;68:1039–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bilgin S, Yilmaz A, Ozdemir F, et al. Extrathoracic staging of non-small cell bronchogenic carcinoma: relationship of the clinical evaluation to organ scans. Respirology. 2002;7:57–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kramer H, Van Putten JWG, Van Dullemen HM, et al. Prospective study of endoscopic ultrasonography with fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) in non-small cell lung cancer patients with positive mediastinal PET. Abstract #1213. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2002;21:304a. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Albes JM, Dohmen BM, Schott U, et al. Value of positron emission tomography for lung cancer staging. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2002;28:55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Goldstraw P, Kurzer M, Edwards D. Preoperative staging of lung cancer: accuracy of computed tomography versus mediastinoscopy. Thorax. 1983;38:10–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wallace MB, Silvestri GA, Sahai AV, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration for staging patients with carcinoma of the lung. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;72:1861–1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]