Abstract

Objectives

To compare a colonic J-pouch or a side-to-end anastomosis after low-anterior resection for rectal cancer with regard to functional and surgical outcome.

Summary Background Data:

A complication after restorative rectal surgery with a straight anastomosis is low- anterior resection syndrome with a postoperatively deteriorated anorectal function. The colonic J-reservoir is sometimes used with the purpose of reducing these symptoms. An alternative method is to use a simple side-to-end anastomosis.

Methods:

One-hundred patients with rectal cancer undergoing total mesorectal excision and colo-anal anastomosis were randomized to receive either a colonic pouch or a side-to-end anastomosis using the descending colon. Surgical results and complications were recorded. Patients were followed with a functional evaluation at 6 and 12 months postoperatively.

Results:

Fifty patients were randomized to each group. Patient characteristics in both groups were very similar regarding age, gender, tumor level, and Dukes’ stages. A large proportion of the patients received short-term preoperative radiotherapy (78%). There was no significant difference in surgical outcome between the 2 techniques with respect to anastomotic height (4 cm), perioperative blood loss (500 ml), hospital stay (11 days), postoperative complications, reoperations or pelvic sepsis rates. Comparing functional results in the 2 study groups, only the ability to evacuate the bowel in <15 minutes at 6 months reached a significant difference in favor of the pouch procedure.

Conclusions:

The data from this study show that either a colonic J-pouch or a side-to-end anastomosis performed on the descending colon in low-anterior resection with total mesorectal excision are methods that can be used with similar expected functional and surgical results.

One hundred patients that underwent low anterior resection for rectal cancer were randomized to receive either colonic J-pouch or a simple side-to-end anastomosis. The data from this study shows that both methods can be used with similar expected functional and surgical results.

An increasing proportion of sphincter-saving operations is used in modern rectal cancer surgery. Abdominoperineal resections were previously considered the method of choice in surgery for tumors in the lower third of the rectum. In more recent years, a restorative resection has many times been found to be both oncologically and surgically feasible, implying low anastomoses. The use of total mesorectal excision (TME) in tumors of the middle of the rectum and even in tumors of the upper rectum also results in low anastomoses.

A well-known and well-described complication after restorative rectal surgery with a straight anastomosis is low-anterior resection syndrome with a postoperatively deteriorated anorectal function, which is related to the anastomotic level.1,2 The use of a colonic reservoir or pouch to mitigate these symptoms was described in 19863,4 and later in randomized studies.5-7 The initially described reservoir was a J-pouch, approximately 8–12 cm long, formed on the descending or sigmoid colon.3,4,8,9 The recommended size of the pouch has successively decreased to about 5–6 cm.10–12 A further development aiming to reduce or minimize the pouch size is a simple side-to-end anastomosis13 that has been described as an alternative to the J-pouch.14 A novel method of increasing the neorectal capacity by performing a coloplasty pouch has also recently been evaluated.15,16 The purpose of this prospective randomized study was to investigate functional and surgical outcome with a pouch or a nonpouch side-to-end anastomosis after standardized TME surgery for rectal cancer where only the descending colon is used.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

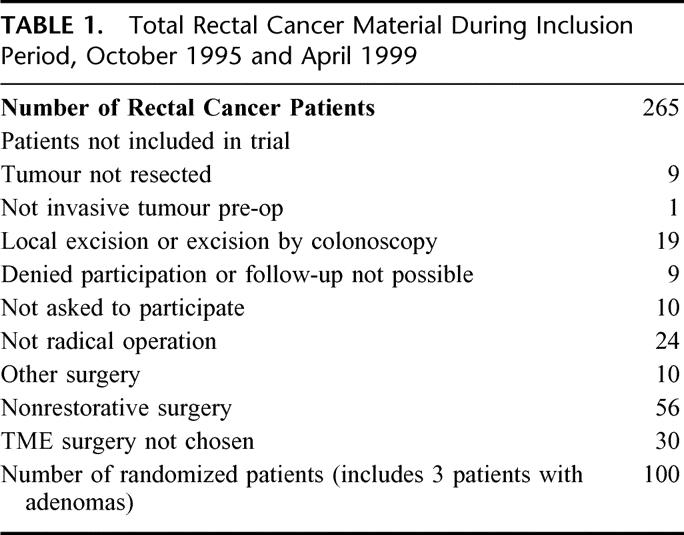

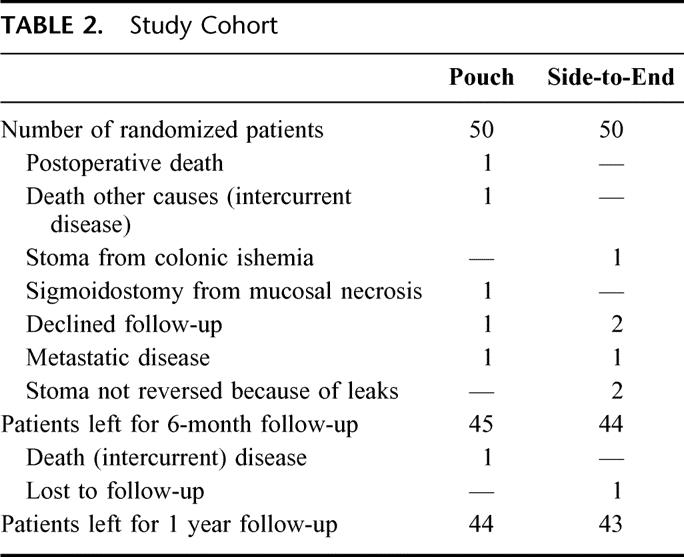

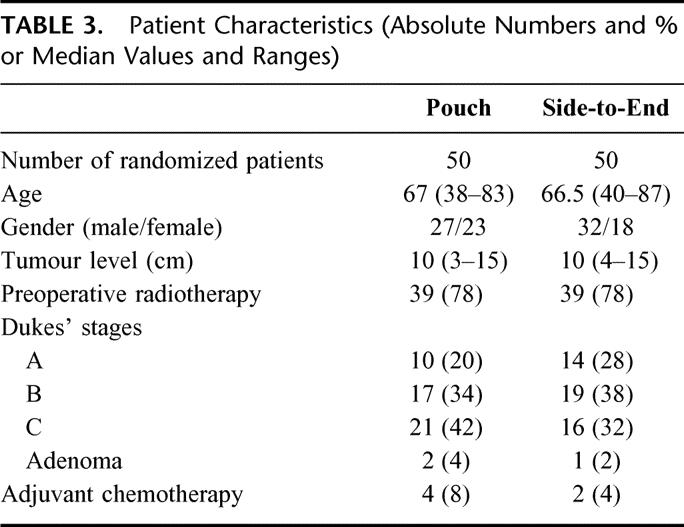

During the study period October 1995 to April 1999, a total of 265 rectal cancer patients were treated at the Centre of Gastrointestinal Disease, Ersta Hospital. Patients with rectal cancer (ie, tumor level ≤ 15 cm from the anal verge) with no demonstrable metastatic disease (as determined from computed tomography scan or magnetic resonance imaging of the abdomen and plain chest x-rays) and where a low-anterior resection was considered feasible were asked to participate in the study. Patients were recruited in a consecutive order if inclusion criteria’s were met and if at least 1 of 3 surgeons involved in the study were on duty. A total of 100 patients were randomized to either a colonic J-pouch (n = 50) or a simple side-to-end anastomosis (n = 50). The reasons for not being included in the trial are given in Table 1. Data were analyzed according to the intention-to-treat principle. Hence, 3 patients found to have adenomas and not rectal cancer in the final pathology were erroneously randomized but have been included in the analysis. Eighty-nine patients could be evaluated after 6 months, and 87 patients could be evaluated after 12 months. Table 2 shows the study cohort and withdrawals. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 3. The groups were comparable with regard to gender, age, tumor level, and distribution of Dukes’ stages. Seventy-eight percent of the patients in both groups had preoperative radiotherapy. It was given as a short-term regimen (5 Gy for 5 days) and surgery was performed the following week.17 In a majority of cases (90%) the anal canal was included in the irradiated field.

TABLE 1. Total Rectal Cancer Material During Inclusion Period, October 1995 and April 1999

TABLE 2. Study Cohort

TABLE 3. Patient Characteristics (Absolute Numbers and % or Median Values and Ranges)

Surgical Techniques and Randomization Procedures

At least 1 of 3 surgeons were present at all operations to ensure the same technique and inclusion criteria. At laparotomy, the abdomen was inspected for metastases. If no metastatic disease could be detected, it was decided whether TME was the appropriate surgery to perform. When this was the case, a standardized rectal resection using TME was conducted, implying sharp dissection in avascular planes down to the pelvic floor. The rectum was divided at the pelvic floor or at a lower level with a PI 30 stapler (Auto Suture, United States Surgical, Norwalk, CT). The inferior mesenteric artery was routinely ligated close to the aorta, the splenic flexure mobilized and the descending colon was transected with a GIA instrument (Auto Suture, United States Surgical).

At this point of the operation, the patients were randomly assigned for either a colonic pouch or a side-to-end anastomosis. The group assignment was selected in batches of 20 closed envelopes. A standardized surgical technique for the anastomosis was then used in all cases. The J-pouch was constructed with a linear GIA 90 stapler (Auto Suture, United States Surgical) introduced trough the apex. The obtained pouch size using this instrument is 8 cm as measured by the vertical staple line. When a side-to-end anastomosis was performed, the anvil of he circular stapler was placed 3–4 cm from the end of the divided bowel. A circular PPCEEA 31 stapler (Auto Suture, United States Surgical) introduced through the anus was used to anastomose the colon to the anal canal or the short rectal remnant. The integrity of the anastomosis was tested with air and by inspecting the “doughnuts.” Primary defunctioning stoma was used in only 1 case where there was a technical difficulty mobilizing the left flexure and a splenectomy was performed.

Definitions of Complications

A reoperation was defined as any return to the operating theater for a surgical procedure during the entire index admission or within 30 days after the primary operation for patients discharged before the first 30 postoperative days. An anastomotic leak was defined as pelvic sepsis. This included all clinical staple line leaks, infectious collections in the pelvis, with or without a proven staple line leak and enterovaginal fistulas. In this material, there is no time limit for the registration of this complication because clinical leaks can be evident at a late stage after the initial operation.18 Anastomotic stricture was defined as when the anastomosis would not accept a rigid standard 2-cm diameter rectoscope at follow-up.

Functional Evaluation

Follow-Up

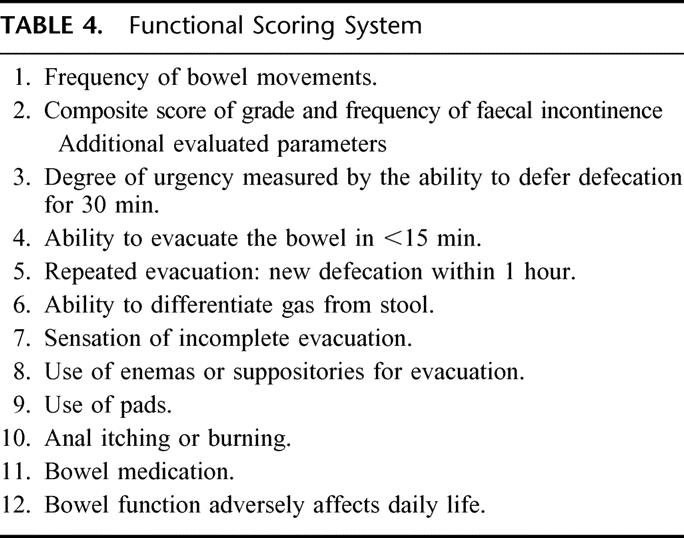

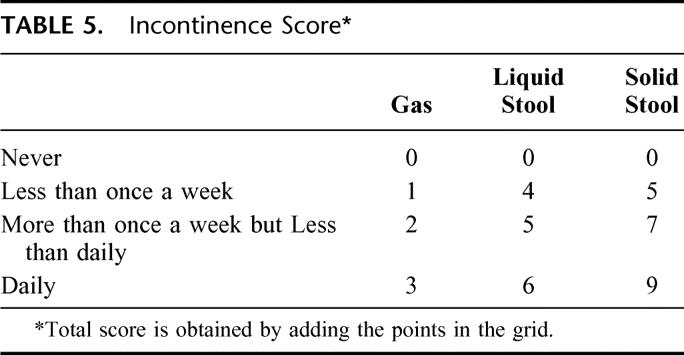

Patients were followed up at 6 and 12 months with a modified functional questionnaire described by Hallböök et al19 (Table 4). The preop functional score was based on the recollection of function before the development of symptoms from the rectal tumor. The patients recorded the number of bowel movements for a week and a 24-hour mean was calculated. This parameter could thus not be determined in the preoperative evaluation. The degree of fecal incontinence was measured with a composite scoring system with a range between 0 and 1819 (Table 5). Each additional parameter was evaluated with the following alternative answer: never, sometimes, often, always; or not at all, a little, quite a bit, very much (Table 4). The answer to each question was categorized in 1 of 2 groups, good function (the 2 most favorable alternatives out of 4 in each question) or poor function, for the statistical analysis. Furthermore, a combined functional rank score was constructed by using the following 4 parameters: number of bowel movements/24 hours, composite score of incontinence, ability to defer defecation for 30 minutes, and ability to empty the bowel in 15 minutes. Patients were ranked by one variable at a time from most favorable to least favorable. The sum of the ranks for each patient was divided by 4 and the mean rank obtained was used as a combined indicator of bowel function.19 Patients with a defunctioning stoma, mainly because of pelvic sepsis, were evaluated the first time 6 months after stoma reversal.

TABLE 4. Functional Scoring System

TABLE 5. Incontinence Score*

Presentation of Data and Statistics

A minimum sample size of 34 patients in each group was estimated to show a reduction in the frequency of daily bowel movements from 3 to 1.7 with a power of 80% and a significance level of 0.05. Calculations were based on a previous study comparing surgical techniques in LAR4 and a pilot study at our own department, indicating a standard deviation of 1.9 bowel movements in 24 hours. It was decided to include a total of 100 patients to ensure a sufficient number of patients to evaluate at 12 months follow-up.

Data are given as absolute numbers and percentages or median values with interquartile ranges. Nonparametric statistics have been used to compare the 2 groups. The Mann–Whitney U test and Fisher exact test was used as appropriate. Data were also tested with a multiple stepwise regression analysis. A value of P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

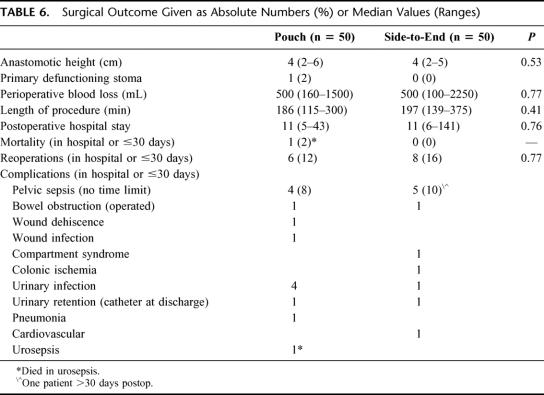

No significant differences in surgical outcome could be detected between patients operated on with a J-pouch or a side-to-end anastomosis. Table 6. The median anastomotic level, measured from the anal verge, was 4 cm in both groups. No significant differences were found in the length of the surgical procedure or in blood losses. The median hospital stay was 11 days for both groups.

TABLE 6. Surgical Outcome Given as Absolute Numbers (%) or Median Values (Ranges)

Postoperative Complications

Details of the postoperative complications are shown in Table 6. One patient in the pouch group died in a fulminant urosepsis after discharge. Nine patients had clinical pelvic sepsis, with an even distribution between the groups. One patient was treated with only local washouts and antibiotics. The other 8 patients with pelvic sepsis were treated with a defunctioning stoma and local washouts. Stoma reversal was performed successfully in 6 of these 8 cases. Altogether, 14 patients were reoperated (14 of 100) and 8 of these interventions were due to pelvic sepsis. During one-year follow up, 2 patients with a side-to-end anastomosis and 1 patient with a J-pouch, developed an anastomotic stricture. The pouch patient required surgical intervention with a circular stapler. Local recurrence has occurred in 1 patient in the total material with a median follow up of 64 months (range, 43–82).

Bowel Function

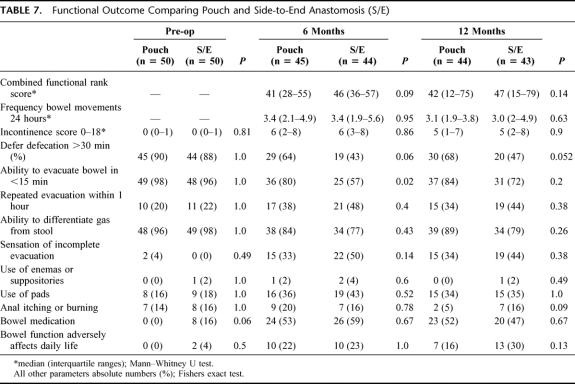

The postoperative functional outcome is summarized in Table 7. Comparing the 2 study groups, only the ability to evacuate the bowel in <15 minutes at 6 months reached a significant difference in favor of a pouch. No difference could be found between the groups in the incontinence scores. Furthermore, stool frequency and the combined functional rank score were similar between the groups at 6 and 12 months.

TABLE 7. Functional Outcome Comparing Pouch and Side-to-End Anastomosis (S/E)

The ability to differentiate gas from stool was good at an early postoperative stage in both groups indicating a preservation of the sampling sensory function. Constipation, defined as need of enemas or suppositories to elicit defecation, was present in only 1 patient, with a side-to-end anastomosis, at 12 months follow up. Preoperative functional assessment of the bowel function was similar between the groups except for bowel medication, which was more frequent in the side-to-end patients (8/50). It is also noteworthy that a considerable proportion of patients in both groups (14–18%) used pads and experienced anal itching or burn in their preoperative habitual state.

In a multiple stepwise regression model, J-pouch or side-to-end anastomosis was not predictive for function (combined functional rank score) when tested with 1 or more of the following variables: age, gender, preop radiotherapy, pelvic sepsis, and anastomotic level.

DISCUSSION

In this prospective randomized study, the functional and surgical outcome was compared between colonic J-pouch and side-to-end anastomosis in low-anterior resection with TME surgery. It was not possible to detect any significant differences in surgical outcome between the groups regarding complications, reoperations, or pelvic sepsis rates. Also, for the functional parameters, there were only minor detectable differences. The data from this study shows that both methods can be used with similar expected surgical and functional results at 6 and 12 months.

The patients studied presently were those with a potentially resectable tumor without signs of spread and where restorative surgery deemed possible to perform. Apart from this, if the patients agreed to participate, there were no other exclusion criteria. During the study period, 37% of all patients treated for rectal cancer at the unit entered the trial. Surgery was standardized as described in detail in the methods section. There were no major technical problems with either of the 2 methods used.

Patients were asked to fill in functional protocols before the operation and were asked to judge their bowel habits before the period of a symptomatic rectal tumor. Obviously, these data are of a “retrospective” nature but they give an indication of the habitual anorectal function in the study sample. The preoperative data indicate that the functional parameters were very similar in the 2 groups, except for the use of bowel medication. Interestingly, a considerable proportion of patients experienced adverse bowel symptoms, measured by the functional questionnaires, as their normal habitual state (Table 6). A recent population based study in Sweden reported a 10% leakage of feces more often than once a month in the case of loose stools.20 Soiling of underclothes occurred more than once a month in 21% of men and in 14.5% of women. The value of some tested parameters in our material could thus be questioned as pertinent outcome measures. The collected data after the operation was assembled prospectively. Thus, for comparison between groups in the postoperative period, the accuracy of these data is more reliable.

Patients were randomized at a late stage of surgery. Thus, after a TME had been performed, and if there were no macroscopical signs of local or distant residual disease, both methods had to be deemed possible to perform before randomization took place. There were only 2 patients in whom it was impossible to perform a pouch because of inadequate length of bowel and a side-to-end anastomosis was preferred. These were the only patients excluded from the study for technical reasons. Thus, there were no systematic errors or major loss of patients in the randomization caused by technical or anatomic reasons.

Previous studies that compare colonic reservoirs to straight anastomoses commonly include follow up already at 1–3 months.5,6 In these and other series, the relative advantage of a colonic pouch over a straight anastomosis has been shown mainly in the early postoperative period.5,21 Barrier at al22 reported long-term outcomes (4-8 years postoperative) that are very similar between conventional straight anastomoses or colonic pouches. In the present study, the first follow up was performed 6 months after the operation. The main reason for this was to avoid any influence from adjuvant chemotherapy given in the setting of an ongoing trial during the first 6 postoperative months. Given the results previously published, it cannot be excluded that there was difference between the randomized groups during the period leading up to 6 months.

The two often cited primary endpoints, the number of bowel movements and fecal incontinence, were similar between the groups. During the entire 1-year follow up, only the ability to evacuate the bowel in <15 minutes at 6 months follow-up reached a significant difference. Lack of power could however explain the absence of significant differences in some other tested parameters. In summary, minor not detectable functional differences are a possibility, but the clinical relevance of these can be debated.

Several studies have reported that patients with colonic pouch can experience evacuation difficulties and constipation.3,11 This problem has been attributed to the size of the reservoir in human23 and animal studies24 and, therefore, smaller pouches have been recommended.10–12 Huber and coworkers compared pouch to side-to-end anastomosis in a randomized study.14 Their conclusion was that the pouch carried a functional advantage especially in the immediate postoperative phase. However, the side-to-end anastomosis was recommended, for functional reasons, instead of a conventional straight anastomosis if pouch construction is technically not possible.

Recent studies have also evaluated another alternative to the pouch, using a coloplasty with the intention to increase the volume of the anastomosed colon.15,16 The obtained neo-rectal volume was comparable to a 6-cm J-pouch. Ho and coworkers states that ensuing bowel function or life quality would minimally influence the choice for either J-pouch or coloplasty.16 A higher anastomotic leak rate in the coloplasty group was, however, a concern. The role of the neo-rectal reservoir principle of the J-pouch has also been questioned as the determinant functional factor. It is instead hypothesized that the functional principle is related to delayed propulsive motility and not an effect of increased neorectal capacity.25 In the present study an 8-cm pouch was used with similar functional results compared with a side-to-end anastomosis. Evacuation difficulties requiring enemas or suppositories was experienced by only 1 patient in the pouch group at 6 months and in no patient at 12 months follow-up. This is markedly less than in other materials with comparable pouch sizes.3,10,26

The colonic segment used for the anastomosis may be an important factor determining postoperative function. In some previous studies that compare the function of pouches with a conventional straight anastomosis, or the role of the pouch size, the part of the colon used for the anastomosis was not clearly defined.7,11 The sigmoid colon is presumed to be unsuitable in pouch surgery for functional reasons6,27 or for technical reasons because of diverticular disease or poor blood supply. In the present material the descending colon was used throughout. The resulting mobilization of the descending colon will potentially lead to an autonomic denervation,28 which could have functional implications. The possibility that the denervation of this segment may be beneficial cannot be excluded but such a speculation must be further explored. However, the only randomized study published so far, showed similar results when TME surgery and pouch was used either on the sigmoid or the descending colon.29

Overall leak rates in rectal cancer surgery vary between 3% and 19% and the risk is higher in low anastomoses.18,30-32 In the literature, the definition of “anastomotic leaks” in LAR varies. It is sometimes not defined.33 Isolated pelvic abscesses without proven leaks and leaks from other staple lines in colonic pouches are also excluded at times.18 Thus, the definitions and values used to measure anastomotic and staple lines failures vary extensively and precludes an accurate comparison of rates between studies and institutions.34 Nevertheless, with a broad definition (ie, pelvic sepsis) leak rates of 5-14% have recently been reported.14,25,29 The frequency of pelvic sepsis in this material with low anastomoses, was 8-10%, including clinical staple line leaks, infectious collections in the pelvis, with or without a proven staple line leaks, and entero-vaginal fistulas. No significant difference in the rate of pelvic sepsis could be found between the pouch and the side-to-end group.

It has been shown that an anastomotic leak implies a risk for patients to end up with a permanent stoma as a direct consequence of this complication.31 In the present study, a successful reversal of the defunctioning stomas was performed in 75% of these patients. There was no difference between the pouch and side-to-end groups regarding other complications, which should not be expected, as the surgery was otherwise standardized.

Anastomotic stricture occurred in only 3 patients (3%) during the follow-up period. By using the same definition, a stricture rate of 10% in the total material has been reported in a study that compared straight and J-pouch anastomosis.5 It can be speculated whether the routine of not using a defunctioning stoma can be 1 factor that contributes to the relatively low frequency of strictures in the present material.

Local recurrence was not a primary end point in this study. However, the low rate found presently (1%) supports an approach in the treatment of rectal cancer with liberal TME surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy.

We conclude that functional and surgical outcome is similar, regardless of whether a colonic J-pouch or side-to-end anastomosis is performed on the descending colon in low anterior resection with TME. The side-to-end anastomosis is technically an easy alternative to perform and can with preference be used when there is inadequate bowel length for a J-pouch or in the anatomically narrow pelvis. From our study it can also be concluded that with the present methodology with extensive mobilization and constant use of the descending colon for anastomosis and 8-cm pouches, the problem with constipation is very small during the first year.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank stoma therapist Annica Wistedt for invaluable help in coordinating the study.

Footnotes

Reprints: Dr Mikael Machado, Centre of Gastrointestinal Disease, Ersta Hospital, P.O. Box 4622, S-116 91 Stockholm, Sweden. E-mail: mikael.machado@ersta.se.

Supported by the Stockholm County Council, Public Health and Medical Services Committee.

REFERENCES

- 1.Miller AS, Lewis WG, Williamson ME, et al. Factors that influence functional outcome after coloanal anastomosis for carcinoma of the rectum. Br J Surg. 1995;82:1327–1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewis WG, Martin IG, Williamson ME, et al. Why do some patients experience poor functional results after anterior resection of the rectum for carcinoma? Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:259–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parc R, Tiret E, Frileux P, et al. Resection and colo-anal anastomosis with colonic reservoir for rectal carcinoma. Br J Surg. 1986;73:139–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lazorthes F, Fages P, Chiotasso P, et al. Resection of the rectum with construction of a colonic reservoir and colo-anal anastomosis for carcinoma of the rectum. Br J Surg. 1986;73:136–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hallbook O, Pahlman L, Krog M, et al. Randomized comparison of straight and colonic J pouch anastomosis after low anterior resection. Ann Surg. 1996;224:58–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seow-Choen F, Goh HS. Prospective randomized trial comparing J colonic pouch-anal anastomosis and straight coloanal reconstruction. Br J Surg. 1995;82:608–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ortiz H, De Miguel M, Armendáriz P, et al. Coloanal anastomosis: are functional results better with a pouch? Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:375–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nicholls RJ, Lubowski DZ, Donaldson DR. Comparison of colonic reservoir and straight colo-anal reconstruction after rectal excision. Br J Surg. 1988;75:318–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kusunoki M, Shoji Y, Yanagi H, et al. Function after anoabdominal rectal resection and colonic J pouch-anal anastomosis. Br J Surg. 1991;78:1434–1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hida J, Yasutomi M, Fujimoto K, et al. Functional outcome after low anterior resection with low anastomosis for rectal cancer using the colonic J-pouch. Prospective randomized study for determination of optimum pouch size. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:986–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lazorthes F, Gamagami R, Chiotasso P, et al. Prospective, randomized study comparing clinical results between small and large colonic J-pouch following coloanal anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:1409–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ho YH, Yu S, Ang ES, et al. Small colonic J-pouch improves colonic retention of liquids–randomized, controlled trial with scintigraphy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baker JW. Low end to side rectosigmoidal anastomosis: description of the technique. Arch Surg. 1950;61:143–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huber FT, Herter B, Siewert JR. Colonic pouch vs. side-to-end anastomosis in low anterior resection. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:896–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Z’graggen K, Maurer CA, Birrer S, et al. A new surgical concept for rectal replacement after low anterior resection: the transverse coloplasty pouch. Ann Surg. 2001;234:780–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ho YH, Brown S, Heah SM, et al. Comparison of J-pouch and coloplasty pouch for low rectal cancers: a randomized, controlled trial investigating functional results and comparative anastomotic leak rates. Ann Surg. 2002;236:49–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swedish Rectal Cancer Trial. Improved survival with preoperative radiotherapy in resectable rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:980–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rullier E, Laurent C, Garrelon JL, et al. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after resection of rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 1998;85:355–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hallböök O, Nystrom PO, Sjodahl R. Physiologic characteristics of straight and colonic J-pouch anastomoses after rectal excision for cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:332–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walter S, Hallbook O, Gotthard R, et al. A population-based study on bowel habits in a Swedish community: prevalence of faecal incontinence and constipation. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:911–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lazorthes F, Chiotasso P, Gamagami RA, et al. Late clinical outcome in a randomized prospective comparison of colonic J pouch and straight coloanal anastomosis. Br J Surg. 1997;84:1449–1451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barrier A, Martel P, Gallot D, et al. Long-term functional results of colonic J pouch versus straight coloanal anastomosis. Br J Surg. 1999;86:1176–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hida J, Yasutomi M, Maruyama T, et al. Enlargement of colonic pouch after proctectomy and coloanal anastomosis: potential cause for evacuation difficulty. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:1181–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sailer M, Debus ES, Fuchs KH, et al. Comparison of different J-pouches vs. straight and side-to-end coloanal anastomoses: experimental study in pigs. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:590–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Furst A, Burghofer K, Hutzel L, et al. Neorectal reservoir is not the functional principle of the colonic J-pouch: the volume of a short colonic J-pouch does not differ from a straight coloanal anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:660–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berger A, Tiret E, Parc R, et al. Excision of the rectum with colonic J pouch-anal anastomosis for adenocarcinoma of the low and mid rectum. World J Surg. 1992;16:470–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams N, Seow-Choen F. Physiological and functional outcome following ultra-low anterior resection with colon pouch-anal anastomosis. Br J Surg. 1998;85:1029–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Catchpole BN. Motor pattern of the left colon before and after surgery for rectal cancer: possible implications in other disorders. Gut. 1988;29:624–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heah SM, Seow-Choen F, Eu KW, et al. Prospective, randomized trial comparing sigmoid vs. descending colonic J-pouch after total rectal excision. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:322–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pakkastie TE, Luukkonen PE, Jarvinen HJ. Anastomotic leakage after anterior resection of the rectum. Eur J Surg. 1994;160:293–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karanjia ND, Corder AP, Bearn P, et al. Leakage from stapled low anastomosis after total mesorectal excision for carcinoma of the rectum. Br J Surg. 1994;81:1224–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vignali A, Gianotti L, Braga M, et al. Altered Microperfusion at the Rectal Stump Is Predictive for Rectal Anastomotic Leak. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pollard CW, Nivatvongs S, Rojanasakul A, et al. Carcinoma of the rectum. Profiles of intraoperative and early postoperative complications. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:866–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bruce J, Krukowski ZH, Al-Khairy G, et al. Systematic review of the definition and measurement of anastomotic leak after gastrointestinal surgery. Br J Surg. 2001;88:1157–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]