Abstract

Objective:

To establish the incidence and causes of late failure in patients undergoing restorative proctocolectomy for a preoperative diagnosis of ulcerative colitis was the objective of this investigation.

Summary Background Data:

Restorative proctocolectomy is the elective surgical procedure of choice for ulcerative colitis. Most patients have a satisfactory outcome but failures occur. The reasons and rates of early failure are well documented, but there is little information on long-term failure.

Methods:

A series of 634 patients (298 females, 336 males) underwent restorative proctocolectomy for inflammatory bowel disease between 1976-1997, with a mean follow-up of 85 ± 58 months. Failure was defined as removal of the pouch or the need for an indefinite ileostomy. It was divided into early and late, occurring within 1 year or more than 1 year postoperatively.

Results:

There were 3 (0.5%) postoperative deaths, leaving 631 patients for analysis. Of these, 23 subsequently died (disseminated large bowel cancer, 12; unrelated causes, 9; related causes, 2).

There were 61 (9.7%) failures (15 early [25%], 46 late [75%]) due to pelvic sepsis (32 [52%]: 7 early, 25 late), poor function (18 [30%]: 2 early, 16 late), pouchitis (7 [11%]: 2 early, 5 late) and miscellaneous (4, all early). A final diagnosis of Crohn’s disease, type of reservoir (J,S), female gender, postoperative pelvic sepsis and a one-stage procedure were significantly associated with failure. Failure rate rose with time of follow-up from 9% at 5 years to 13% at 10 years.

Conclusions:

Pelvic sepsis and poor function were the main reasons for later failure. Failure rates should be reported based on the duration of follow-up.

Over 22 years, 634 patients underwent restorative proctocolectomy for inflammatory bowel disease. At a mean follow-up of 85 months, overall failure was 9.7% with pelvic sepsis and poor function being the commonest reasons. Failure was cumulative with time, with a prevalence of 9% at 5 years rising to 13% at 10 years.

Restorative proctocolectomy with ileal reservoir has become the operation of choice for ulcerative colitis1-4, but major and minor complications occur which, in some patients, may affect function or lead to pouch excision or indefinite diversion. Early failure is well documented in the literature1-9, but there is little information on long-term failure. With more than 20 years’ experience of this operation, it was felt appropriate to try and establish the incidence and causes of late failure.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Between July 1976 and December 1997, 634 patients underwent restorative proctocolectomy for inflammatory bowel disease. Last follow up recorded was in December 2000. Assessment of the patients at routine follow-up and review of the research records and case notes were supplemented by telephone interview or direct approach to the clinician if the patient was being followed elsewhere.

Patient Population

There was a slight male predominance (336 males, 298 females) and the mean age at operation was 34.7 years (range, 9-73 years). The final pathologic diagnoses included ulcerative colitis in 611 patients (96.4%), indeterminate colitis in 10 (1.6%) and Crohn’s disease in 13 (2%). The reservoir design was of the W type in 296 patients (47%), J in 202 (32%), Kock (K) in 90 (14%) and S in 46 (7%).

Most patients had a diverting ileostomy fashioned during the original pouch procedure, but 123 (19.5%) did not. The ileostomy was closed a mean of 114 days after the initial operation.

Five hundred seventy-two patients (91%) had completed follow-up at 1 year, 394 (62%) at 5 years and 183 (29%) at 10 years. Patients were followed for a mean of 85 ± 58 months.

Mortality

Of the 634 patients, 26 (4%) died. These included 3 postoperative deaths (0.5%), each due to pulmonary complications. In addition, there were 2 operation-related deaths, both due to septicemia at 17 and 19 months after surgery. Altogether, this is an operation-related mortality of 0.8%. Of the remaining 21 patients, 12 patients died of disseminated colorectal cancer and 9 of a variety of unrelated causes including myocardial infarction, status epilepticus, road traffic accident, renal insufficiency, and noncolorectal malignancy (5 patients).

Definition

Failure was defined either as the need to remove the pouch and establish a permanent ileostomy or the need for an ileostomy without prospect of closure. It was divided into early and late, the former occurring within 1 year and the latter at more than 1 year from restorative proctocolectomy.

For the purpose of the study, the 3 postoperative deaths were excluded and analysis was based on the denominator of 631 survivors of the operation.

Patients who experienced failure were compared with those with an intact reservoir at the time of the study to identify possible factors associated with failure, including age, gender, type of pouch, final pathologic diagnosis and the occurrence of pelvic sepsis at the original operation.

Statistical Analysis

Comparisons of proportions were made by using the χ2 test for categorical variables and Student’s t test for continuous variable (age). The cumulative probability of pouch failure was estimated by means of Kaplan–Meier analysis. Results are expressed as mean ± SD. Probability values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Probability of failure was modeled by multivariate logistic regression model.

RESULTS

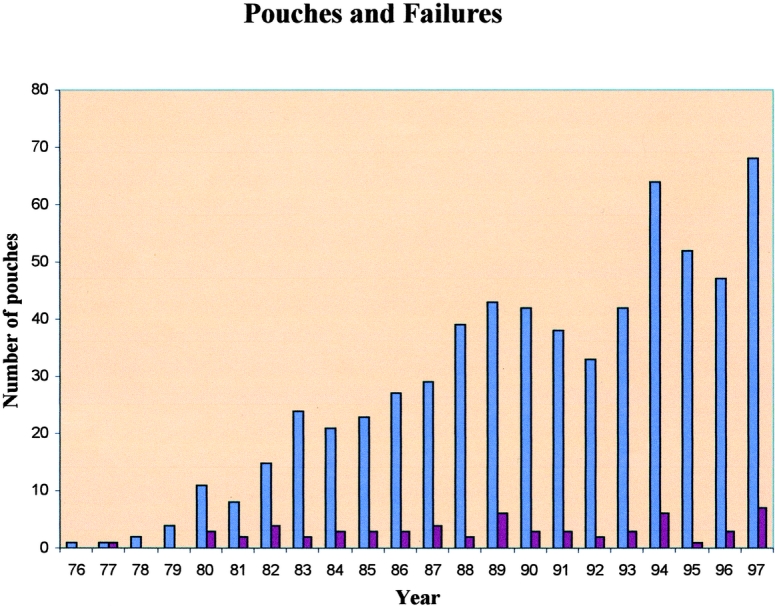

Sixty-one of the 631 operation survivors experienced failure, giving an overall failure rate of 9.7%. Of these, the pouch had been excised in 41 instances; in 20, a long-term ileostomy had been performed. The number of operations and failures by year since 1976 is shown in Figure 1. The incidence of failure, expressed as a percentage for each year (Fig. 2), has significantly decreased from 16.5% during the first 11-year period to 8.3% during the second (P = 0.008).

FIGURE 1. Number of operations and failures by year, 1976–1997.

FIGURE 2. Incidence of failure expressed as a percentage by year, 1976–1997.

The causes of failure are shown in Table 1. Fifteen (25%) occurred early and 46 (75%) were late. Pelvic sepsis accounted for approximately 50% of the failures in each group. The majority of late failures was due to fistulation into the vagina (11 patients) or perineum (7 patients), or to previously unrecognized Crohn’s disease (6 patients). Of 18 failures due to poor function, 16 were late, with outlet obstruction (5 patients) and sphincter dysfunction (6 patients) accounting for most of these. Pouchitis was responsible for failure in 11% of the cases, and 4 early failures were due to technical reasons.

TABLE 1. Causes of Failure

The prevalence of failure in relation to the final histopathological diagnosis, type of reservoir and occurrence of pelvic sepsis at the time of the original operation is shown in Table 2. Patients with Crohn’s disease had a significantly higher failure rate compared with those with ulcerative colitis or indeterminate colitis (P < 0.001). Initial pelvic sepsis was associated with increased failure as well (P = 0.002). The prevalence of failure was significantly greater in patients having J or S reservoir compared with a W or K design (P < 0.001). Comparison of J reservoir to the W as well as the K design showed the failure incidence to be significantly higher in the group of patients with J pouch (P = 0.001, P = 0.02 respectively).

TABLE 2. Prevalence of Failure According to Diagnosis, Type of Reservoir and Occurrence of Pelvic Sepsis After the Initial Restorative Proctocolectomy

One-stage restorative proctocolectomy (ie, without a covering ileostomy) was associated with a significantly higher incidence of failure compared with a two-stage procedure, 15% versus 8% (P < 0.016). There was no significant difference in age at the time of operation between patients who failed and those with an intact reservoir (mean 33.3 ± 11 and 34.8 ± 11 years, respectively). Females had a significantly higher failure rate compared with males (36/259 [12.2%] and 25/311 [7.4%], respectively; P = 0.043). Because pouch failure is a multifactorial event, multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed. It showed that failure was associated with a one-stage procedure (P < 0.001), initial pelvic sepsis (P = 0.017) and Crohn’s disease (P = 0.002). There was also some correlation to the J reservoir and female gender (P = 0.05).

Life-table analysis of the cumulative incidence of failure (Fig. 3) showed a continuing progression during the period of follow-up. The cumulative incidence at 5 years was 9%; at 10 years, it had risen to 13%.

FIGURE 3. Life-table analysis of failure (Kaplan–Meier).

DISCUSSION

Published failure rates after restorative proctocolectomy range from 3% to 17%.5–10 In most reports, the period of follow-up was short compared with the mean of 85 months in the present study. Although the early failure of 3% was similar to other reports in the literature, most failures occurred late. Furthermore, the data show that failure continues steadily with time without any apparent evidence of a reduction in the rate. Thus, over the entire period of the study, it had risen to a cumulative value of 13%. Others have also reported increasing failure with increasing duration of follow-up.

The rate of failure in the first 11-year period was twice that occurring in the second. The lower cumulative failure rate of patients operated in the second period compared with the first indicates that this difference is not due to the effect of time itself. There are various possible reasons for this improvement, including greater familiarity with the procedure, the fall in rate of pelvic sepsis, the move away from the S reservoir and the increasing use of salvage surgery.11–13

It is noteworthy, however, that failure in patients who did not have a covering ileostomy was significantly higher than in those in whom this was included. Because one-stage procedures tended to be done in the latter half of the period, the effect of this factor will have accounted for some failures that may have been avoidable. These data suggest that a defunctioning ileostomy is of benefit to patients.

As reported by others,8–10,14,15 sepsis is the most common reason for failure and is the most important factor in 33-70% of the patients who fail. Thus, Korsgen and Keighley8 found it was the cause in 35.5%. Of 58 failures (10.5%) out of 551 patients followed for a minimum of 30 months, MacRae et al9 reported 39% to be caused by leakage from the ileoanal anastomosis. In a group of 45 failures out of 924 patients followed for a mean of 35 (range, 1-125) months, Fazio et al14 reported 15 (33%) to be due to pelvic sepsis, including pouch fistula. Galandiuk et al16 found sepsis and/or fistula to be responsible for 73% of the 3.8% failures in a large series of patients. These studies, however, included patients who had received restorative proctocolectomy for familial adenomatous polyposis in which the incidence of postoperative sepsis, pouchitis and failure is lower than for patients with ulcerative colitis.17,18

Of the 32 failures due to sepsis in the present study, the majority occurred late. Eighteen of the total were caused by fistulation from the reservoir to the vagina or perineum, and most occurred beyond 1 year after restorative proctocolectomy. Failure due to sepsis was, therefore, mainly a late event and was related to pelvic septic complications in the immediate postoperative period. Techniques of salvage surgery for the treatment of fistulation have improved19,20, and failure caused by this complication may in the future become less common as a consequence. The occurrence of pouch-vaginal fistula would explain the higher incidence of failure in females.

It is noteworthy that failure was higher in patients confirmed histologically to have Crohn’s disease compared with those with ulcerative colitis or indeterminate colitis. This result is in line with general experience21-24, except for that of Regimbeau et al.25 The reason for the good results obtained by these authors is not clear. Although case selection seems to be important, the distinction between Crohn’s disease and indeterminate colitis may be a factor.

Poor function was confined almost entirely to patients experiencing late failure. This finding is not surprising, because it takes time for the patient and surgeon to agree that continuing poor function is untenable. In this series as well as in others,5,10,16 poor function accounted for about one-third of failures. Thus, Gemlo et al5 reported a 9.9% failure rate, with poor function as the cause in 7 (28%) of 25 patients; Meagher et al10 found it to be the second most frequent reason.

Outlet obstruction at the level of the ileoanal anastomosis is a common cause of dysfunction resulting in the frequent passage of small volume stool and accounted for 5 failures in the present study. In some cases, this was due to the distal ileal segment associated with the S reservoir, which was significantly more associated with failure than other reservoir types. Its discontinuation may be one factor for the improvement of results in the second half of the period. Salvage surgery for mechanical outflow obstruction had been developed also in the latter part of the period and was not available in the early years. Had it been available, some of the failures at the beginning might have been avoided.

Pouchitis, defined as symptomatic inflammation of the ileal reservoir, occurs in 7-40% of cases.26-32 In about 10% of patients, the condition is chronic and unremitting, being refractory to medical treatment. This result is reflected by the relatively small proportion of failures due to pouchitis in the present study, which is similar to the experience of others.6,14,33

In summary, the majority of pouch failures occur more than 1 year after restorative proctocolectomy, and about 80% are caused by pelvic sepsis, with or without fistulation, and by poor function. Pouchitis is an uncommon cause. Failure continues indefinitely with time. Its incidence has fallen over the 22-year period of follow-up. This finding has been associated with a fall in the rate of immediate postoperative pelvic sepsis, discontinuation of the S reservoir and the increasing availability of salvage surgery. A defunctioning ileostomy seems to protect against failure. Cumulative failure at 5 years was 9% and at 10 years 13%. Failure rates should be reported on the basis of the duration of follow-up.

Footnotes

Reprints: R. J. Nicholls, St. Mark’s Hospital, North West London Hospitals NHS Trust, Watford Road, Harrow, Middlesex HA1 3UJ, United Kingdom. E-mail: John.Nicholls@nwlh.nhs.uk.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nicholls RJ, Moskowitz RL, Shepherd NA. Restorative proctocolectomy with ileal reservoir. Br J Surg. 1985;72:S76–S79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wexner SD, Wong WD, Rothenberger DA, et al. The ileoanal reservoir. Am J Surg. 1990;159:178–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelly KA. Anal sphincter saving operations for chronic ulcerative colitis. Am J Surg. 1992;1:5–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Becker JM. Surgical management of inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 1993;9:600–615. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gemlo BT, Wong WD, Rothenberger DA, et al. Ileal pouch anal anastomosis—patterns of failure. Arch Surg. 1992;127:784–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Setti Carraro P, Ritchie JK, Wilkinson KH, et al. The first 10 years’ experience of restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1994;35:1070–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foley EF, Schoetz DJ Jr, Roberts PL, et al. Rediversion after ileal pouch anal anastomosis: causes of failures and predictors of subsequent pouch salvage. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:793–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korsgen S, Keighley MRB. Causes of failure and life expectancy of the ileoanal pouch. Int J Colorect Dis. 1997;12:4–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacRae HM, McLeod RS, Cohen Z, et al. Risk factors for pelvic pouch failure. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:257–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meagher AP, Farouk R, Dozois RR, et al. J ileal pouch anal anastomosis for chronic ulcerative colitis: complications and long-term outcome in 1310 patients. Br J Surg. 1998;6:800–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sagar PM, Dozois RR, Wolff BG, et al. Disconnection, pouch revision and reconnection of the ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Br J Surg. 1996;83:1401–1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fazio VW, Wu JS, Lavery IC. Repeat ileal pouch-anal anastomosis to salvage septic complications of pelvic pouches. Ann Surg. 1998;4:588–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tulchinsky H, McCourtney JS, Subba Rao KV, et al. Salvage abdominal surgery in patients with a retained rectal stump after restorative proctocolectomy with stapled anastomosis. Br J Surg. 2001;88:1602–1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fazio VW, Ziv Y, Church JM, et al. Ileal pouch anal anastomoses complications and function in 1005 patients. Ann Surg. 1995;222:120–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Belliveau P, Trudel J, Vasilevsky CA, et al. Ileoanal anastomosis with reservoirs: complications and long-term results. Can J Surg. 1999;42:345–352. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galandiuk S, Scott NA, Dozois RR, et al. Ileal pouch anal anastomosis: reoperation for pouch-related complications. Ann Surg. 1990;212:446–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nicholls RJ. Restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch reservoir: indications and results. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1990;120:485–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dozois RR, Kelly KA, Welling DR, et al. Ileal pouch anal anastomosis: comparison of results in FAP and UC. Ann Surg. 1989;210:268–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fazio VW, Tjandra JJ. Pouch advancement and neoileoanal anastomosis for anastomotic stricture and anovaginal fistula complicating restorative proctocolectomy. Br J Surg. 1992;79:694–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burke D, Van Laarhoven CJHM, Herbst F, et al. Transvaginal repair of pouch-vaginal fistula. Br. J Surg. 2001;88:241–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deutsch AA, McLeod RS, Cullen J, et al. Results of pelvic pouch procedure in patients with Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34:475–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grobler SP, Hosie KB, Affie E, et al. Outcome of restorative proctocolectomy when the diagnosis is suggestive of Crohn’s disease. Gut. 1993;34:1384–1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sagar PM, Dozois RR, Wolff BG. Long-term results of ileal pouch and anastomosis in patients with Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:893–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hyman NH, Fazio VW, Tuckson WB, et al. Consequences of ileal pouch anal anastomosis for Crohn’s colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34:653–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Regimbeau JM, Panis Y, Pocard M, et al. Long-term results of ileal pouch anal anastomosis for colorectal Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:769–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nicholls RJ, Belleveau P, Neill M, et al. Restorative proctocolectomy with ileal reservoir: a pathophysiological assessment. Gut. 1981;22:462–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keighley MR. The management of pouchitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1996;10:449–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zuccaro G, Fazio VW, Church JM, et al. Pouch ileitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1989;34:1505–1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Warren BF, Bartolo DCC, Collins CMP. Preclosure pouchitis: a new entity. J Pathol. 1990;160:A170. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tytgat GNJ, van Deventer SJH. Pouchitis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1988;3:226–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Madden MV, Farthing MJG, Nicholls RJ. Inflammation in ileal reservoirs: “pouchitis”. Gut. 1990;31:247–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Silva HJ, Kettlewell MGW, Mortensen NJ, et al. Acute inflammation in ileal pouches (pouchitis). Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1991;3:343. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marcello PW, Roberts PL, Schoetz DJ, et al. Long-term results of the ileoanal pouch procedure. Arch Surg. 1993;128:500–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]