Abstract

Objective:

To determine the contemporary clinical relevance of acute lower extremity ischemia and the factors associated with amputation and in-hospital mortality.

Summary Background Data:

Acute lower extremity ischemia is considered limb- and life-threatening and usually requires therapy within 24 hours. The equivalency of thrombolytic therapy and surgery for the treatment of subacute limb ischemia up to 14 days duration is accepted fact. However, little information exists with regards to the long-term clinical course and therapeutic outcomes in these patients.

Methods:

Two databases formed the basis for this study. The first was the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) from 1992 to 2000 of all patients (N = 23,268) with a primary discharge diagnosis of acute embolism and thrombosis of the lower extremities. The second was a retrospective University of Michigan experience from 1995 to 2002 of matched ICD-9-CM coded patients (N = 105). Demographic factors, atherosclerotic risk factors, the need for amputation, and in-hospital mortality were assessed by univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis.

Results:

In the NIS, the mean patient age was 71 years, and 54% were female. The average length of stay (LOS) was 9.4 days, and inflation-adjusted cost per admission was $25,916. The amputation rate was 12.7%, and mortality was 9%. Decreased amputation rates accompanied: female sex (0.90, 0.81-0.99), age less than 63 years (0.47, 0.41-0.54), angioplasty (0.46, 0.38-0.55), and embolectomy (0.39, 0.35-0.44). Decreased mortality accompanied: angioplasty (0.79, 0.64-0.96), heparin administration (0.50, 0.29-0.86), and age less than 63 years(0.27, 0.23-0.33).

The University of Michigan patients’ mean age was 62 years, and 57% were men. The LOS was 11 days, with a 14% amputation rate and a mortality of 12%. Prior vascular bypasses existed in 23% of patients, and heparin use was documented in 16%. Embolectomy was associated with decreased amputation rates (0.054, 0.01-0.27) and mortality (0.07, 0.01-0.57).

Conclusions:

In patients with acute limb ischemia, the more widespread use of heparin anticoagulation and, in select patients, performance of embolectomy rather than pursuing thrombolysis may improve patient outcomes.

The contemporary treatment of acute lower extremity ischemia was examined using an administrative database and a single institutional experience. National trends of amputation, mortality, and costs are presented and factors associated with outcomes determined.

Acute lower extremity ischemia is a common vascular disease and is a cause of considerable morbidity and mortality. In 2000, abdominal aortic and lower extremity arterial embolism and thrombosis affected 213,000 patients in the United States.1 Hospitalization costs of treating the individual patient range from $6000 to $45,000.2-4

In an evolving era of less invasive therapies, several randomized controlled clinical trials have suggested that catheter-directed thrombolysis is as effective as surgical revascularization in preventing limb-loss and mortality in these patients.4-8 Unfortunately, most such trials included patients with ischemic insults ranging from 7 to 14 days in duration. These patients may have subacute, not critical, limb ischemia, having a longer window for re-establishing blood flow and a lesser reperfusion injury. In addition, many patients in these trials had a history of chronic occlusive disease and some had prior arterial bypasses as the target for thrombolytic therapy. A distinction between subacute (SVS Class I) and true limb-threatening ischemia (SVS classes IIa, Iib, and III) becomes relevant regarding the urgency of care and risk of limb loss.9

Endovascular catheter-directed thrombolysis may be appropriate for limb-threatening ischemia, but it usually takes longer to return blood flow to the limb, is associated with increased risk of major hemorrhage, and increases costs due to repeated arteriography and longer ICU care compared with surgical therapy. The latter shortcomings must be balanced against open thrombectomy’s greater physiological stress on an already ill patient and the possibility that an urgent bypass may be needed.10-11

Obvious factors related to improved outcomes are: (1) precise patient categorization of the degree of ischemia; (2) etiology as judged by history and physical examination; and (3) an appropriate therapeutic intervention. The current study was undertaken using a database representing the United States population to define the contemporary national impact of acute lower extremity ischemia, coupled with a retrospective review of data from a single institution that carefully restricted the categorization of ischemia and identified those factors that reduce the rates of amputation and death.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

National Data

The Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) represents a 20% stratified random sample of all hospital discharges in the United States that is maintained by the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research as part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. The current investigation studied patients discharged from 1992 to 2000 with an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) primary diagnostic code for abdominal aortic embolism and thrombosis (ICD-9-CM code 44.40), lower extremity embolism and thrombosis (ICD-9-CM code 444.22), or iliac artery embolism and thrombosis (ICD-9-CM code 444.81). The study population was limited to those patients having an emergent or urgent admission. Patients with the procedure code for bypass graft (ICD-9-CM code 39.29) were excluded to further restrict the study population to those with acute, rather than subacute, or chronic limb ischemia. This study population was also evaluated for the following: heparin administration (ICD-9-CM code 99.19), fasciotomy (ICD-9-CM code 83.14), angioplasty (ICD-9-CM code 39.50 from 1995 to 2000, and 39.59 from 1992 to 1995), thrombolytic therapy (ICD-9-CM code 99.10 from 1998 to 2000, and 99.29 from 1992 to 1998), embolectomy (ICD-9-CM codes 38.06, 38.08), and amputation (ICD-9-CM codes 84.15, 84.17).

Single Institutional Data

A retrospective review was performed of University of Michigan Hospital patient records from the study period of 1995 to 2002. A total of 105 consecutive patients treated for acute lower extremity ischemia were identified for study. These patients all had the same ICD-9-CM codes used for the NIS database review. Patients were excluded when thromboses were due to iatrogenic injuries, such as intra-aortic balloon pump, or occurred as postoperative complications from another surgical procedure, such as abdominal aortic aneurysm repair.

Outcome Variables

The primary outcome variables were amputation rate and in-hospital mortality. Length of stay (LOS) was used as a secondary outcome in the NIS review to assess changes in resource use over time. Failed thrombolysis was used as an additional assessment of outcomes in the University of Michigan analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics of baseline characteristics were performed. Univariate analysis by χ2 testing for categorical variables and T-testing for continuous variables were used for comparative analyses. Factors found significant by univariate analysis were included in a linear regression model to determine the independence of the individual factors. P < 0.05 was considered significant in all final analyses. Statistical assessments were performed using SPSS Version 11.0 (Chicago, IL) for all NIS data and SAS 8.0 (Cary, NC) for the University of Michigan data.

RESULTS

NIS Patient Characteristics and Therapeutic Trends

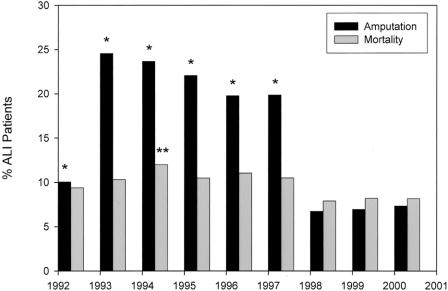

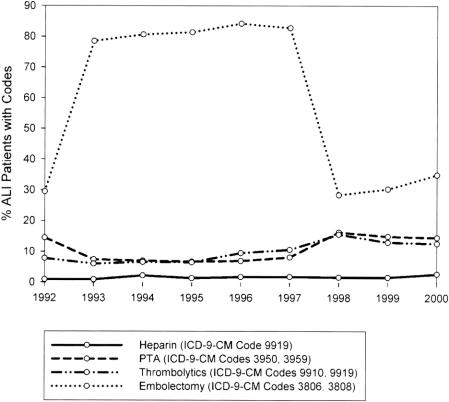

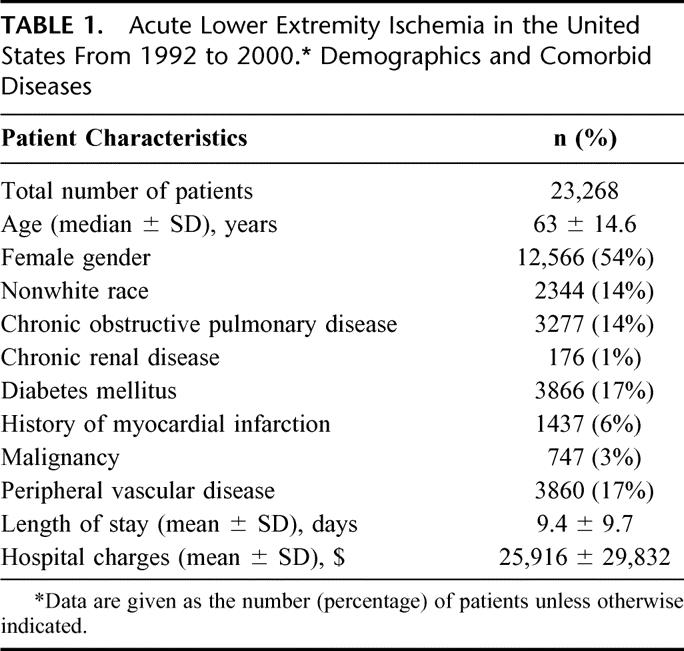

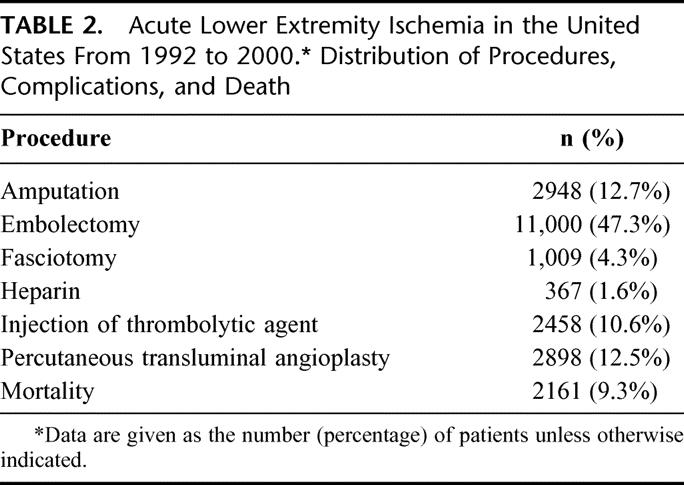

Patient characteristics, length of stay, and the average adjusted cost per admission were revealing (Table 1), as were the interventions and their outcomes (Table 2). Amputation was undertaken in 12.7% of patients. The in-hospital death rate was 9%. A marked and sustained increase in amputation rates occurred between 1992 (10%) and 1993 to 1997 (25-20%), with a decrease (approaching 7%) noted from 1998 to 2000. Mortality rates followed a similar trend, but with less variation (Fig. 1). Certain procedures also showed variations over time (Fig. 2). For example, embolectomy increased from 1992 (29%) to 1993 to 1997 (79-83%), but decreased by 1998 to 2000 (28-34%). Thrombolytic therapy and angioplasty between 1997 and 1998 increased 1.5-fold and 2-fold, respectively. However, coding for heparin administration never exceeded 3%.

TABLE 1. Acute Lower Extremity Ischemia in the United States From 1992 to 2000. Demographics and Comorbid Diseases

TABLE 2. Acute Lower Extremity Ischemia in the United States From 1992 to 2000. Distribution of Procedures, Complications, and Death

FIGURE 1. National trends in the frequency of amputation and in-hospital death over time in patients with acute lower extremity ischemia. *Significant difference (P < 0.05, multivariate logistic regression) in amputation rate when compared with the year 2000. **Significant difference (P < 0.05, multivariate logistic regression) in mortality rate when compared with the year 2000.

FIGURE 2. National trends in the frequency of procedures over time in patients with acute lower extremity ischemia.

NIS Amputation and Mortality

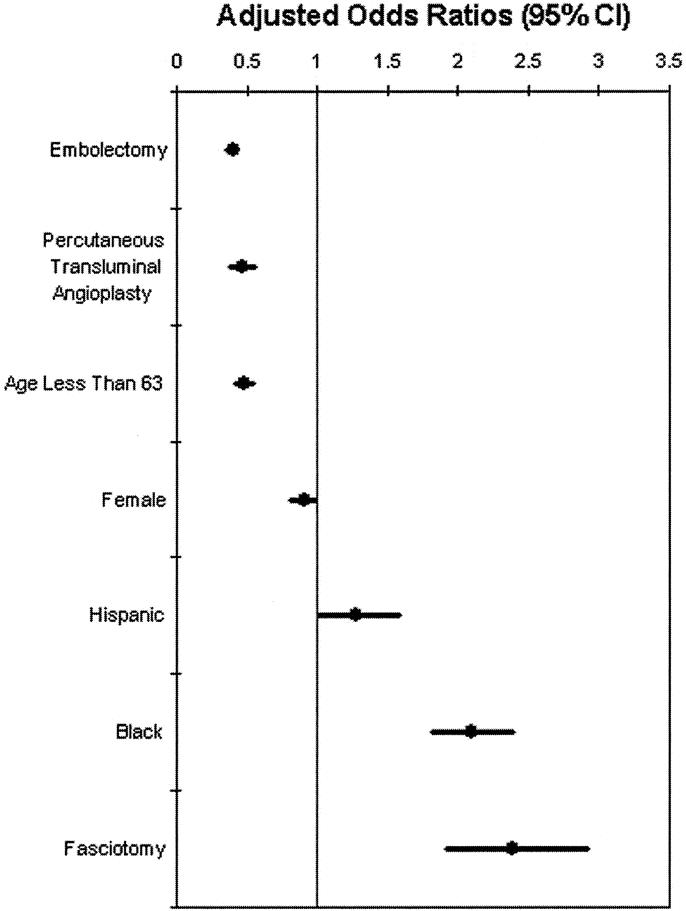

Thrombolytic therapy was not significantly associated with decreased amputation or mortality. Decreased risk of amputation (Fig. 3) accompanied: embolectomy (OR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.35 to 0.44; P < 0.001), percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) (OR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.38 to 0.55; P < 0.001), age less than 63 years (OR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.41 to 0.54; P < 0.001), and female gender (OR, 0.90, 95% CI, 0.81 to 0.99). An increased risk of amputation accompanied: Hispanic race (OR, 1.26, 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.58), African-American race (OR, 2.08, 95% CI, 1.81 to 2.39), and the performance of fasciotomy (OR, 2.37; 95% CI, 1.93 to 2.92; P < 0.001).

FIGURE 3. National risk of amputation associated with acute lower extremity ischemia. The performance of embolectomy, percutaneous transluminal angioplasty, age less than 63 years, and female gender were associated with decreased amputation rates, whereas Hispanic race, African-American race, and performance of fasciotomy were associated with increased amputation rates. CI, confidence interval. Note: Heparin administration did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.154).

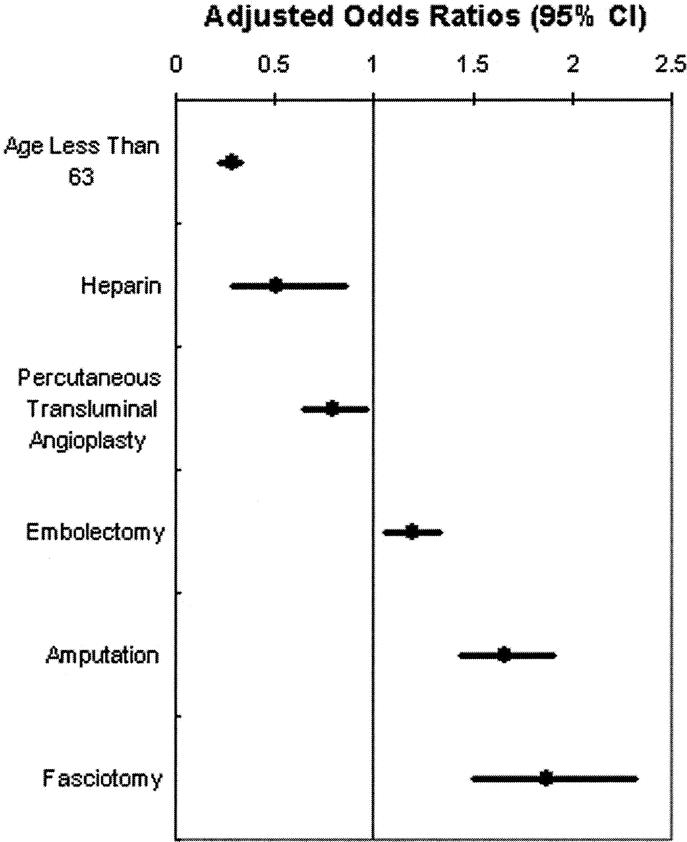

Independent variables associated with decreased risk of in-hospital mortality (Fig. 4) were: age less than 63 years (OR, 0.27; 95% CI, 0.23 to 0.33; P < 0.001), heparin administration (OR, 0.50; 95% CI, 0.29 to 0.86; P = 0.012), and percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (OR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.64 to 0.96; P = 0.019). An increasing risk of in-hospital mortality was associated with performance of embolectomy (OR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.06 to 1.33; P = 0.002), amputation (OR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.44 to 1.90; P < 0.001), and fasciotomy (OR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.50 to 2.32; P < 0.001).

FIGURE 4. National risk of mortality associated with acute lower extremity ischemia. Age less than 63 years, heparin administration, and percutaneous transluminal angioplasty were associated with decreased mortality, whereas the performance of embolectomy, amputation, and fasciotomy were associated with increased mortality. CI, confidence interval. Note: African-American race (P = 0.781) and Hispanic race (P = 0.269) did not reach statistical significance.

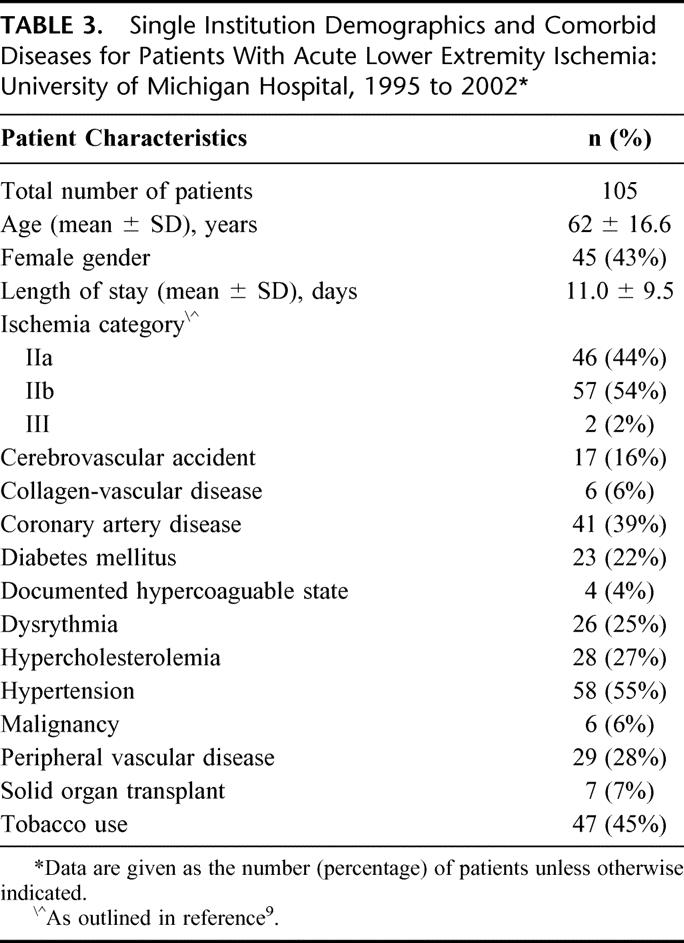

Single Institution Patient Characteristics

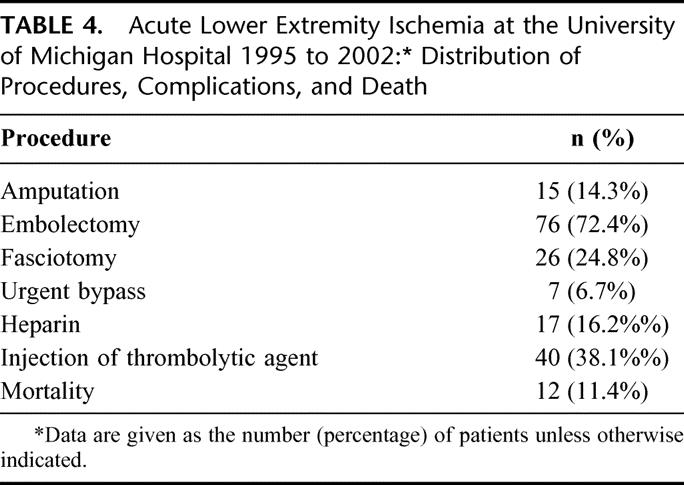

Among the 105 patients treated at the University of Michigan Hospital, there were 55 men (57%) and 45 women (43%). The average length of stay was 11.0 ± 9.5 days. Excluding 12 in-hospital deaths (11.4%), the mean follow-up in this study was 12.0 ± 15.9 months. Amputation was undertaken in 14.3% of patients. The category of ischemia and major comorbidities were revealing (Table 3), as were other therapeutic interventions and outcomes (Table 4). There were slightly more category IIb patients (54%) than IIa patients (44%), and only 2 patients (2%) had category III ischemia. A history of peripheral vascular disease existed in 29% of patients, and only 45% of patients used tobacco. Catheter directed thrombolytic therapy was undertaken in 40 patients and was successful in providing restoration of blood flow in 18. Of the 22 patients that failed thrombolytic therapy, 6 amputations were performed and there were 3 deaths. The remaining 14 patients underwent embolectomy resulting in another 2 deaths, 4 amputations, and 3 urgent bypasses.

TABLE 3. Single Institution Demographics and Comorbid Diseases for Patients With Acute Lower Extremity Ischemia: University of Michigan Hospital, 1995 to 2002

TABLE 4. Acute Lower Extremity Ischemia at the University of Michigan Hospital 1995 to 2002: Distribution of Procedures, Complications, and Death

Single Institution Amputation and Mortality

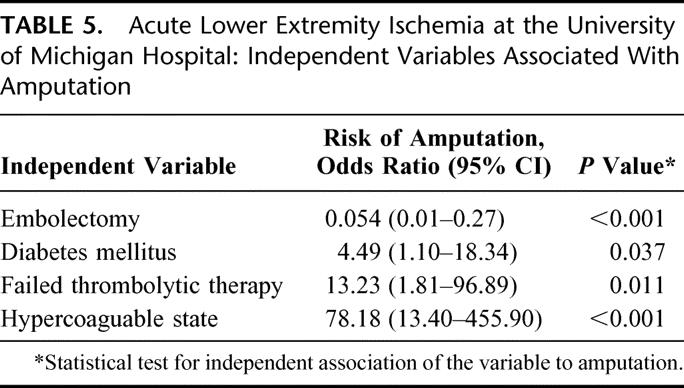

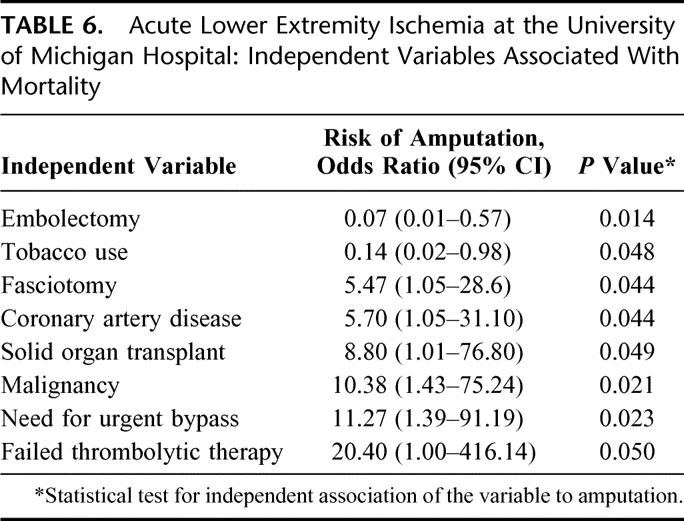

The independent variables associated with both amputation (Table 5) and mortality (Table 6) revealed only embolectomy to reduce both (amputation: OR, 0.054; 95% CI, 0.01 to 0.27; P < 0.001; mortality: OR, 0.07; 95% CI, 0.01 to 0.57; P = 0.014). Failed thrombolytic therapy was a risk factor for both amputation and mortality (amputation: OR, 13.23; 95% CI, 1.81 to 96.89; P = 0.011; mortality: OR, 20.40; 95% CI, 1.00 to 416.14; P = 0.050). In subanalysis, tobacco use was associated with an increased risk of failed thrombolysis (OR, 4.96; 95% CI, 1.02 to 24.19; P = 0.048).

TABLE 5. Acute Lower Extremity Ischemia at the University of Michigan Hospital: Independent Variables Associated With Amputation

TABLE 6. Acute Lower Extremity Ischemia at the University of Michigan Hospital: Independent Variables Associated With Mortality

DISCUSSION

Acute lower extremity ischemia continues to be associated with significant limb loss and mortality despite advances in endovascular-based therapies and overall improved critical care. To put the mortality rate in perspective, acute lower extremity ischemia mortality is approximately one third that of similar time frame acute myocardial infarction (NIS 1997 to 2000, unpublished data), and nearly threefold greater than mortality after elective abdominal aortic aneurysm repair.12 This less than salutary outcome has occurred despite more than a decade of experience with thrombolytic therapy and the advent of new catheter-based treatments, such as mechanical thrombectomy.13-14 The NIS mean mortality rate is compatible with other contemporary reported series, but not appreciably better than those series from more than 20 years ago.15-18 Part of the reason for this is the severe underlying diseases that are present in many of these patients, of which an acute embolic process may be a manifestation. For example, from our institutional analysis, CAD, DM, malignancy, and prior transplant were independently associated with poor outcome. This mortality rate is also a reflection of ischemia-reperfusion injury in many treated patients. Reactive oxygen intermediaries may cause secondary cellular damage, not only in the reperfused extremity, but also at remote organ sites.19

The national impact of published level I evidence promulgating the use of thrombolytic therapy for acute limb ischemia5-8 was evident in the decreased utilization of operative catheter embolectomies after 1998. Conversely, the number of patients undergoing thrombolysis and angioplasty increased. Interestingly, a corresponding decrease in amputation rate from 19.9% to 6.7% was observed after 1998. While it is possible that increased use of thrombolytics resulted in decreased amputations, it is impossible to define a direct cause and effect relationship using an administrative database. In this regard, use of thrombolytics was not independently associated with a decreased amputation rate by multivariate regression analysis.

The NIS has been validated for the purpose of identifying in-hospital events, especially major complications in surgical patients.20 However, this administrative database has certain significant limitations. For example, patient comorbidities included in the demographic data were not included in univariate or logistic analysis because comorbidities coded on the index admission may appear protective, as sicker patients have more disease codes than less sick patients. The scope of this study did not attempt to validate each comorbidity with additional clinical information.21 Furthermore, the specific therapies listed for a patient are subject to undercoding, and often depend on nonphysician chart abstractors to determine clinical diagnoses and therapies rendered. There are also some coding variables that could not be controlled. For example, the current code for infusion of thrombolytic agents (ICD-9-CM 99.10) was first published in 1998. Before 1998, the ICD-9-CM code 99.19 was used, but it included injection or infusion of a platelet inhibitor (Now ICD-9-CM 99.20) and administration of neuroprotective agent (Now ICD-9-CM 99.75). Similarly, the ICD-9-CM code 39.50 for angioplasty or atherectomy of a noncoronary vessel was first published in 1995. Before 1995, the ICD-9-CM code 39.59 included “other repair of vessel” and was thus a nonspecific code that captured any vessel repair that did not have its own code. These 2 changes in ICD-9-CM coding may have overestimated the prior number of NIS patients truly receiving thrombolytic therapy or angioplasty.

The fact that thrombolytic therapy was used in more than 2400 patients over the study period with no significant reduction in amputation or mortality contrasts with the strongly protective effect of heparin use in decreasing mortality. It was striking that only 367 of the 23,268 NIS patients were coded for heparin infusion. This may underrepresent the number of patients who actually received heparin. However, in-depth record review of the University of Michigan Hospital also revealed a very low percentage (16%) of patients who received heparin. This might not have been expected given Blaisdell’s benchmark report that documented the value of heparin administration in the initial management of all patients with acute lower extremity ischemia not having an absolute contraindication to its use, such as traumatic injury.22 These findings suggest that a standard of care is still lacking for this group of patients.10,11,23 Also, in addition to its beneficial anticoagulant properties, heparin has an antiinflammatory effect such as cell adhesion molecule inhibition that also may be protective against the ischemia-reperfusion injury in these patients.24

The single institutional experience at the University of Michigan Hospital, while not large, was striking in the significant number of patients who failed thrombolytic therapy. This translated into a 13-fold increase in limb-loss and 20-fold increase in mortality. Thus, the failed thrombolysis group of 22 patients accounted for 60% of the amputations and 41.7% of the mortality in this review. It may be hypothesized that patients who failed thrombolytic therapy had a delay in reperfusion, and timely reperfusion has been proven essential for improving limb salvage and decreasing mortality.11,23,25 Patients who failed thrombolytic therapy may also have had more complex disease that would have been difficult to treat by any means. However, the fact that only 3 of the 14 patients who went from failing thrombolysis to surgical embolectomy required an urgent bypass suggests that they had embolic disease and may have been inappropriately chosen for thrombolytic therapy. It is important to note that the group that failed thrombolytic therapy did not have more medical comorbidities, a higher incidence of peripheral vascular occlusive disease, or a more severe grade of ischemia. Interestingly, tobacco use was independently associated with increased failure of thrombolytic therapy. Lastly, the fact that only 25% of patients had a documented dysrhythmia from the institutional data suggests that aortic plaque and thrombus may occur more commonly than generally recognized as a cause of acute lower extremity ischemia in most series.23,25

An important observation of this study was that embolectomy was highly protective against amputation at both the national and institutional level, as well as mortality at the institutional level. This supports the preferential use of embolectomy in patients with a high likelihood of an embolic etiology of their ischemia.10,25,26 The benefits of open surgical embolectomy are rapid restoration of blood flow and the ease of the procedure, whereas the risks include a greater physiological stress and concomitant blood loss. The benefits of endovascular approaches with thrombolytic agents are arteriographic delineation of the occlusion and a potential to open smaller vessels, whereas the main risks are contrast nephropathy and catheter-related thromboses or bleeding. Technological advances with aspiration catheters as well as adjunctive glycoprotein IIB/IIIA platelet receptor antagonists are promising in terms of providing a means to more rapidly restore blood flow to an ischemic limb than what current endovascular therapies allow.13,14,27

Longer durations of ischemia often mandate 4 compartment fasciotomies, but these are associated with significant increases in amputation and mortality, both nationally and at the institutional level. While fasciotomies are often performed in patients with more advanced ischemia and may be judged necessary, the current data suggest that this therapy may yield little benefit to patients.

The current study reflects the fact that acute limb ischemia continues to be a common and costly problem with significant morbidity and mortality. Many risk factors denoting poor outcomes cannot be changed. However, data from the reported national and institutional databases suggest that better outcomes may accompany the more common use of heparin anticoagulation and performance of embolectomy rather than thrombolysis in properly selected patients with acute lower extremity ischemia.

Discussions

Dr. John A. Mannick (Boston, Massachusetts): Dr. Eliason and Dr. Henke and their coworkers have tried to find out what is going on in the real world in the treatment of acute lower extremity ischemia about 7 years after the Stiles and Topaz investigators adequately demonstrated that thrombolysis has some efficacy in the treatment of patients with lower extremity ischemia.

They have used 2 databases to do this, as you heard. The first is the NIS data, which is a very large data pool. There are some problems with it since it is very difficult to know how accurately it is coded. And then they have used a retrospective review in their own institution, the University of Michigan, to try to make their analysis more accurate. A couple of concerns that prompt questions:

One of them is that in looking at the NIS data, that is the national survey, they find that at about the time the Stiles and Topaz investigators reported, embolectomy plunged as a technique that was used to manage patients with acute lower extremity ischemia. The results seemed to improve at the same time. This simply cannot be explained, if you believe the NIS data, by a corresponding increase in use of thrombolitics or heparin, which increased a bit but not sufficiently to explain the results.

My first question is, what do you think really happened around 1997 or 1998? Is this all coding error? I find it hard to believe that therapeutic nihilism is doing better than heparin, thrombolysis or embolectomy in terms of patient management.

Second, with respect to the more reliable Michigan data, the authors conclude that there is a real place for embolectomy. This certainly goes along with my own prejudices. But before we accept that conclusion, it is probably necessary to at least think about the possibility that those people who got embolectomy may not have been quite the same group of patients as those who got thrombolysis.

As you know, it is very difficult to equate the restoration of flow to a limb that has had an embolus into a normal arterial tree from that in a limb where thrombosis is caused by progression of severe atherosclerotic disease and compare that again with a limb that has had a chronically functioning bypass graft that suddenly failed. It may well be that embolectomy is better for 1 of these groups of patients than another, and I wonder if you have any information about this issue.

I thank you and your co-authors for providing me with the paper well in advance of the meeting. I enjoyed both reading and hearing about the study and I look forward to your answers.

Dr. Jonathan L. Eliason (Ann Arbor, Michigan): Thank you, Dr. Mannick. You pointed out in your first question that this administrative base is a potentially heterogeneous population and difficult to extrapolate information from, and I am sure that affects our data as well.

We didn’t go back and stratify our data by years and apply multivariate logistic regression analysis to the end-points of amputation and in-hospital mortality year by year. So if you take the series as a whole, thrombolysis did not have a statistical association with either. But, perhaps if we stratified year by year with the publishing of The New England Journal Topaz trial in 1998, and followed the rates during the same time, we might see difference, and that is a good point.

Regarding the variable patient population, and which patients may have gone to embolectomy versus thrombolysis in our own series, we did find that these groups of patients did not have a significant difference in the listed number of comorbidities in their hospital charts. So these were not statistical differences between the 2 groups. However, that doesn’t tell the whole story as to which ones were thought to have embolic disease, which ones had in situ thrombosis, and the few number that had present arterial bypass grafts that may have thrombosed. So it is difficult retrospectively to tease this out.

However, I think the subanalysis of the patients that went to thrombolysis, failed, and then went back to embolectomy was revealing, as only 3 of those patients required a bypass procedure. And it was a very morbid thing to fail thrombolysis. So I think it argues again that 1 shouldn’t discount the use of thrombolysis, but rather be very careful in selecting the patients that go for thrombolytic therapy.

I think the other take-home message from the national database reinforces Blaisdell’s original benchmark article regarding heparin anticoagulation, I think that heparin is something that probably still is underutilized despite the literature that supports its use.

Dr. K. Craig Kent (New York, New York): Dr. Eliason, very nice job in your presentation and a good analysis of a great deal of data. I am very concerned about the data that came from the national database though.

You try to define a subgroup patients who had acute arterial occlusions, yet you tell us that only 4% of those patients received heparin. For most of us the standard of care in patients with acute arterial occlusion is treatment with heparin. So there must be 1 of 2 problems: Either there was undercoding of the use of heparin or the other possibility is that the group that you have chosen includes patients that don’t have acute arterial occlusion. Perhaps included within your cohort are a large number of patients who have subacute occlusions or chronic arterial ischemia. Either way, I am concerned about the validity of your conclusions from that data set.

Did you do anything to validate that the diagnosis code that you used was in fact identifying patients with acute arterial occlusions? Did you go back and review a sampling of patient charts?

Dr. Jonathan L. Eliason (Ann Arbor, Michigan): Thank you, Dr. Kent. No, we did not go back and try and validate the specific diagnosis code of heparin administration or other diagnostic codes to see if, in fact, there were correct diagnoses.

I think the positive predictive value on surgical diagnosis codes has been shown to be about 88% based on administrative databases such as this. So there is error that is inherent in this system. When you include more than 1 ICD-9 code, the error is multiplied. But the scope of this study did not include going back and trying to validate those.

We used some external cohorts to look at whether heparin use was indeed a low frequency of coding in the administrative database, and in that is where the error came from. When we looked at our own series and tried to document preoperative use of heparin in any form by the chart we could only locate it in 16%.

So either that means that the coding by the chart abstracters in the national database and our own documentation of heparin use is very low, or, in fact, even though heparin has been shown to be protective we are not using it often enough. So I can’t clearly answer your question regarding the national database because we didn’t go back and try and validate for those codes.

Dr. Edward D. Verrier (Seattle, Washington): The striking data in 1998 were that your increase in amputation went up so significantly. At our institution probably 1 of the more common causes of acute limb ischemia has to do with intra-aortic balloons. And around this time large percutaneous technologies would have been introduced with big sheets. Did either 1 of those factors come into either 1 of these databases as an etiology of why there seemed to be a change around that time?

Dr. Jonathan L. Eliason (Ann Arbor, Michigan): As far as the institutional review, we excluded those patients, so they were not included in that data set. As far as the national review, they certainly could have impacted this patient group and altered the number of patients that went for embolectomy, as they may not have had embolic disease and required, rather, local arterial repair and thrombectomy or bypass.

One interesting coding variable that was introduced in 1988 was the injection of thrombolic agents. That code used to be different. Between 1997 and during the year 1998 that the changed - to be specific for injection of a thrombolytic agent. Prior to that, it included injection of a platelet inhibitor and injection of a neuro protective device. So there is a coding variable there that was not addressed in my presentation, but it certainly may have been a component in the way the numbers fell out.

Dr. O. Wayne Isom (New York, New York): I haven’t done 1 of these for probably 30 years. But as I recall, 1 of the quickest ways to get kicked off of a vascular service was to see 1 of these patients in the emergency room and not start heparin immediately. And we see the same thing in acute myocardial infarctions.

One thing that has not been mentioned - and I will ask this as a question. Maybe you have this information in your study. The timing from occlusion or symptoms until the time therapy is instituted, whether it is heparin, thrombolytic therapy, or reestablishment of flow, is tremendously important. After 2 or 3 hours of occlusion, the microcirculation starts to obstruct, you are going to have a major problem, and usually an amputation. Can you make any comments about the timing from the start of symptoms to the time of therapy?

Dr. Jonathan L. Eliason (Ann Arbor, Michigan): No. We did not specifically look at that variable, although your point is well taken and we probably should have in our retrospective review. There was no way to analyze that data in the administrative database.

Footnotes

Presented at the 123rd Annual Meeting of the American Surgical Association, Washington, DC, April 25th, 2003.

Reprints: Peter K. Henke, MD, 1500 East Medical Center Drive, Taubman Center 2210, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-0329; E-mail: henke@umich.edu

REFERENCES

- 1.National Hospital Discharge Survey Data. [database online]. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2002. Updated November, 2002.

- 2.Singh S, Evans L, Datta D, et al. The costs of managing lower limb-threatening ischaemia. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1996;12:359-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoch JR, Tullis MJ, Acher CW, et al. Thrombolysis versus surgery as the initial management for native artery occlusion: efficacy, safety, and cost. Surgery. 1994;116:649-656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ouriel K, Shortell CK, De Weese JA, et al. A comparison of thrombolytic therapy with operative vascularization in the initial treatment of acute peripheral arterial ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 1994;19:1021-1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The STILE Investigators. Results of a prospective randomized trial evaluating surgery verses thrombolysis for ischemia of the lower extremity. Ann Surg. 1994;220:251-268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ouriel K, Veith FJ, Sasahara AA, for the TOPAS Investigators. Thrombolysis or peripheral arterial surgery: phase I results. J Vasc Surg. 1996;23:64-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weaver FA, Comerota AJ, Youngblood M, et al. Surgical revascularization versus thrombolysis for nonembolic lower extremity native artery occlusions: results of a prospective randomized trial. The STILE Investigators. Surgery versus thrombolysis for ischemia of the lower extremity. J Vasc Surg. 1996;24:513-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ouriel K, Veith FJ, Sasahara AA. For the TOPAS Investigators. A comparison of recombinant urokinase with vascular surgery as initial treatment for acute arterial occlusion of the legs. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1105-1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rutherford RB, Baker JD, Ernst C, et al. Recommended standards for reports dealing with lower extremity ischemia: revised version. J Vasc Surg. 1997;26:517-538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henke PK. Approach to the patient with acute limb ischemia: diagnosis and therapeutic modalities. Cardiol Clin. 2002;20:513-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Constantini V, Lenti M. Treatment of acute occlusion of peripheral arteries. Thromb Res. 2002;106:V285-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dimick JB, Stanley JC, Axelrod DA, et al. Variation in death rate after abdominal aortic aneurysmectomy in the United States. Ann Surg. 2002;235:579-585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ansel GM, George BS, Botti CF, et al. Rheolytic thrombectomy in the management of limb ischemia: 30-day results from a multicenter registry. J Endovasc Ther. 2002;9:395-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zehnder T, Birrer M, Do DD, et al. Percutaneous catheter thrombus aspiration for acute or subacute arterial occlusion of the legs: how much thrombolysis is needed? Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2000;20:41-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neuzil DF, Edwards WH, Mulherin JL, et al. Limb ischemia: surgical therapy in acute arterial occlusion. Am Surg. 1997;63:270-274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Braithwaite BD, Birch PA, Heather BP, et al. Management of acute leg ischemia in the elderly. Br J Surg. 1998;85:217-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davies B, Braithwaite BD, Birch PA, et al. Acute leg ischaemia in Gloucestershire. Br J Surg. 1997;84:504-508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nypaver TJ, Whyte BR, Endean ED, et al. Nontraumatic lower-extremity acute arterial ischemia. Am J Surg. 1998;176:147-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blaisdell FW. The pathophysiology of skeletal muscle ischemia and the reperfusion syndrome: a review. Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;10:620-630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lawthers AG, McCarthy EP, Davis RB, et al. Identification of in-hospital complications from claims data: is it valid? Med Care. 2000;38:785-795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Finlayson EV, Birkmeyer JD, Stukel TA, et al. Adjusting surgical mortality rates for patient comorbidities: more harm than good? Surgery. 2002;132:787-794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang L, Brown JR, Varki A, et al. Heparin’s anti-inflammatory effects require glucosamine 6-0-sulfation and are mediated by blockade of L- and P-selectins. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:127-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blaisdell FW, Steele M, Allen RE. Management of acute lower extremity ischemia due to embolism and thrombosis. Surgery. 1978;84:822-834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greenberg RK, Ouriel K. Arterial thromboembolism. In: Rutherford RB, eds. Vascular surgery. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Company; 2000:822-835. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Panetta T, Thompson JE, Talkington CM, et al. Arterial embolectomy: a 34-year experience with 400 cases. Surg Clin N Am. 1986;66:339-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palfreyman SJ, Booth A, Michaels JA. A systemic review of intra-arterial thrombolytic therapy for lower extremity ischaemia. Eur J Endovasc Surg. 2000;19:147-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Drescher P, Crain MR, Rilling WS. Initial experience with the combination of reteplase and abciximab for thrombolytic therapy in peripheral arterial occlusive disease: a pilot study. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2002;13:37-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]