Abstract

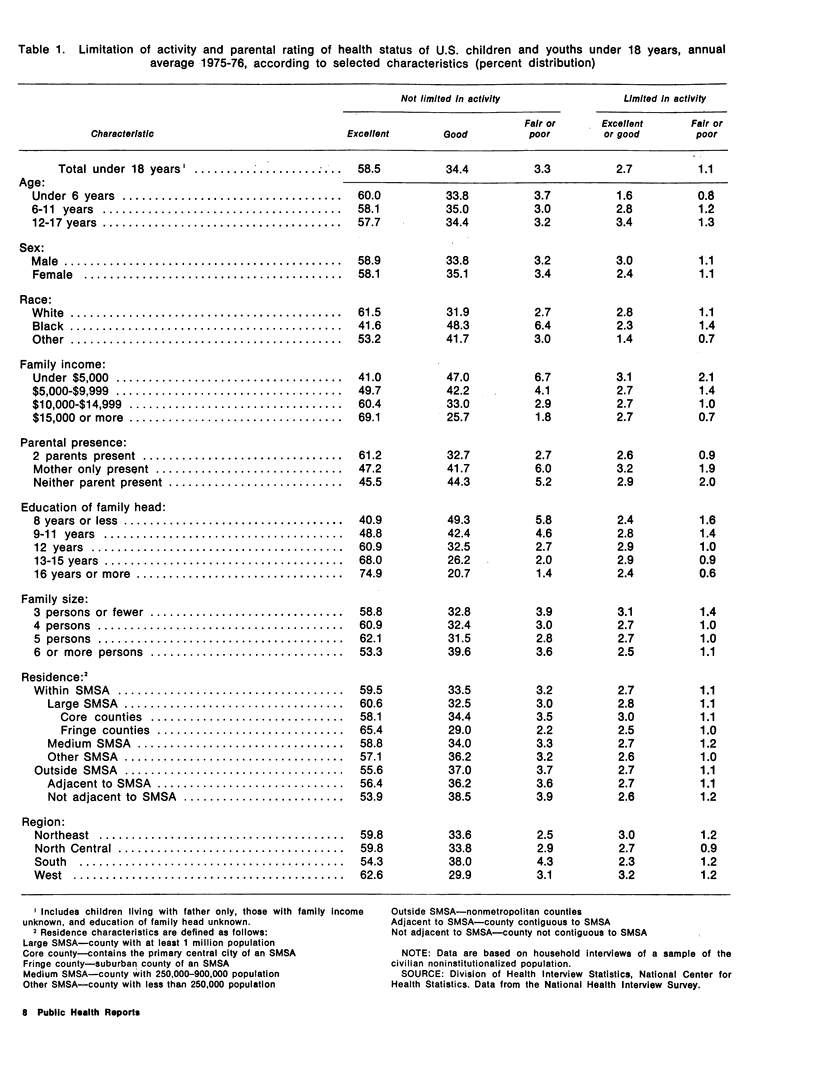

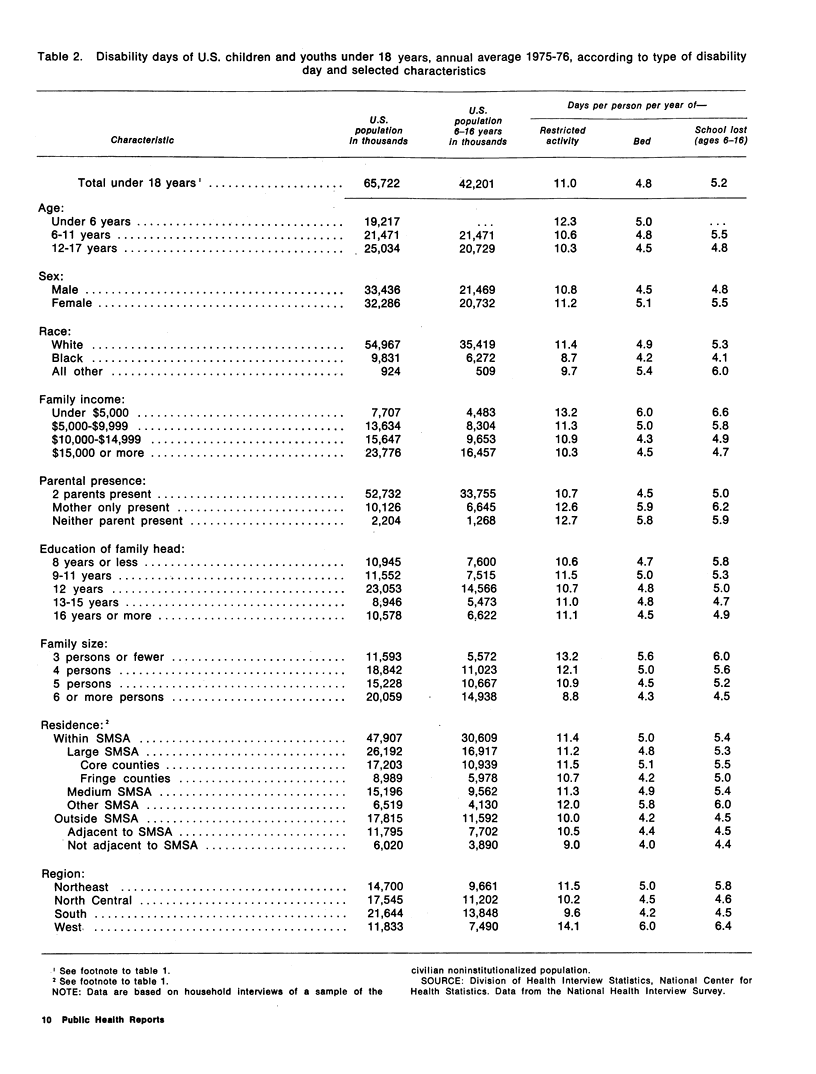

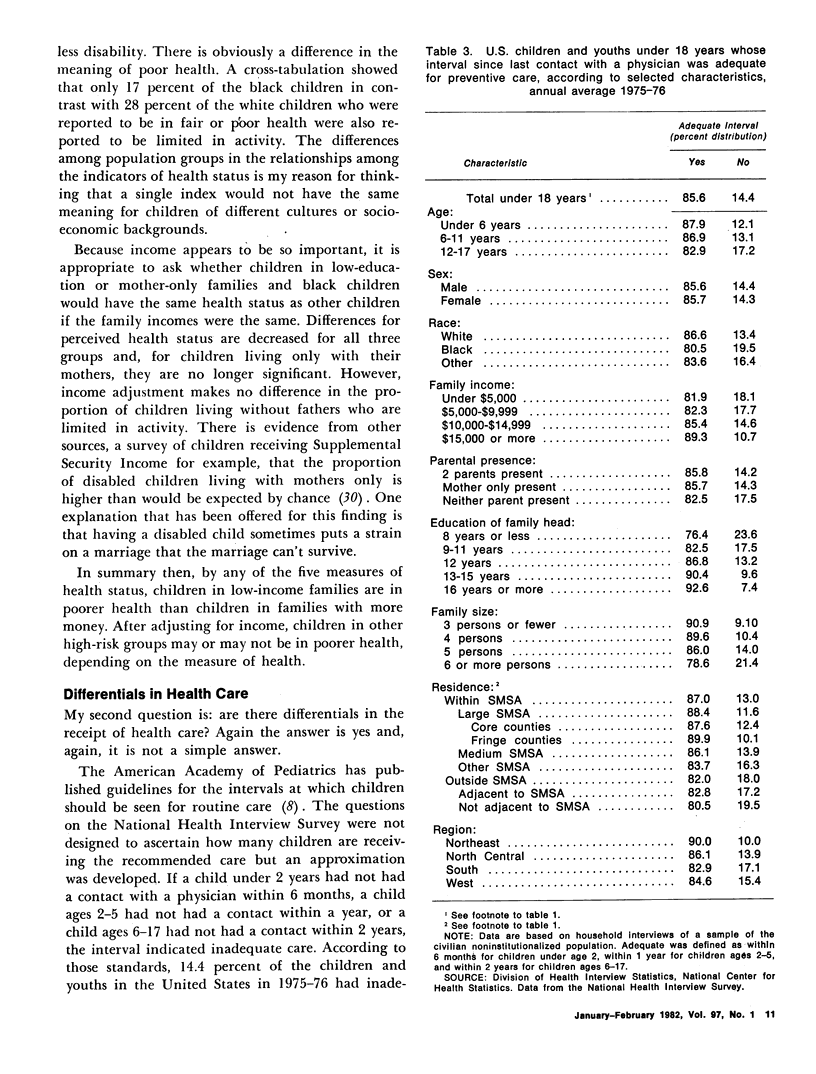

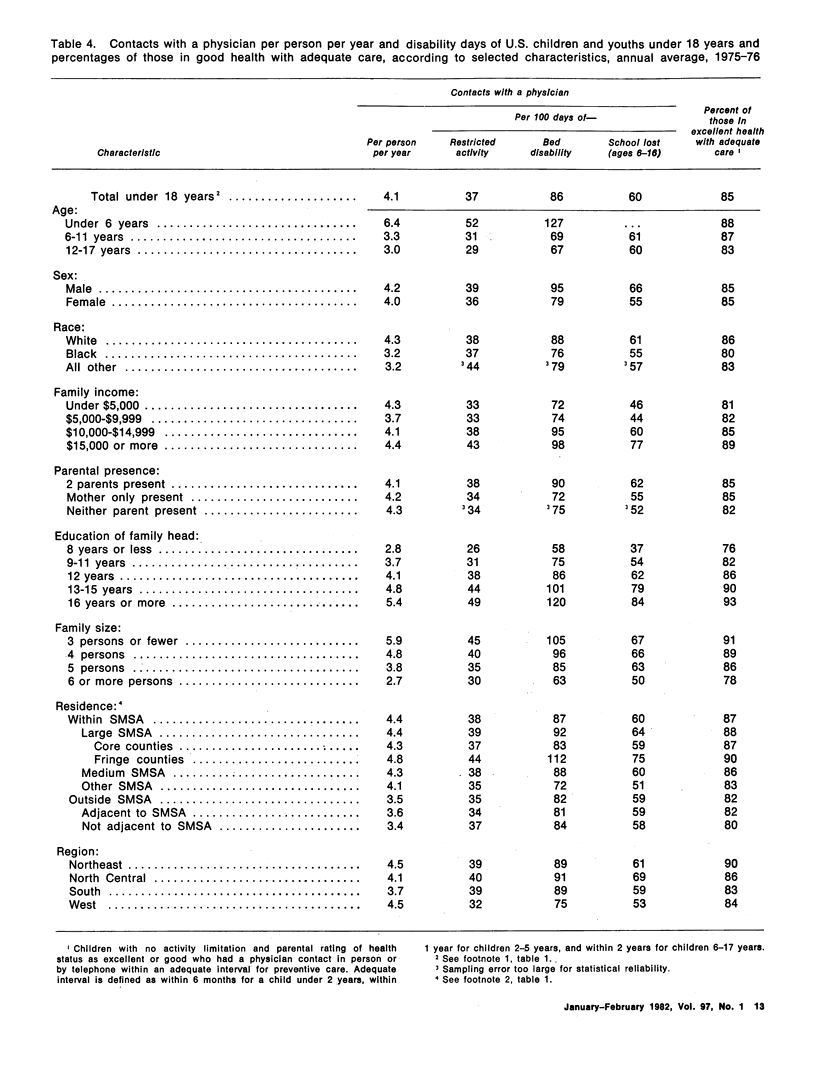

By the traditional measures of health status-mortality rates- the health of children in the United States has greatly improved. Fom 1970 to 1979 the infant mortality rate declined from 20.0 to 13.0 per 1,000 live births. The mortality rate per 100,000 children ages 1-4 years declined from 84 to 63. The decline in mortality appears to have been accomplished without a rise in morbidity. Despite the impressive achievements, 10 years after the implementation of Medicaid poor children were still in poorer health than children in families with more money and were still receiving less medical care relative to need. The differentials that existed before the Medicaid program had decreased, but they had not disappeared. If the ideal is that all parents will report that their children are in excellent health and are not limited in activity by any chronic condition, 2 out of 5 children and youths under 18 years of age did not have ideal health in the mid-1970s. Less than half the children in poor or poorly educated families, black children, or children living without fathers in the household achieved that ideal. If a goal for medical care is that children under age 2 have had a contact with a physician within 6 months, children ages 2-5 within a year, and children ages 6-17 within 2 years, 14 percent of U.S. children and youths did not achieve that relatively modest goal. About a quarter of the children in poorly educated families or families with six or more members had not had a contact with a physician that recently. Tooth decay is one of the most prevalent problems of childhood, yet in 1975-76, 38 percent of the children ages 4-17 had not seen a dentist within a year. More than half the children in poorly educated families, black children, or children in low-income families had not seen a dentist that recently.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Brunswick A. F., Boyle J. M., Tarica C. Who sees the doctor? A study of urban black adolescents. Soc Sci Med Med Psychol Med Sociol. 1979 Jan;13A(1):45–56. doi: 10.1016/0160-7979(79)90007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunswick A. F., Collette P. Psychophysical correlates of elevated blood pressure: a study of urban black adolescents. J Human Stress. 1977 Dec;3(4):19–31. doi: 10.1080/0097840X.1977.9936817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunswick A. F. Indicators of health status in adolescence. Int J Health Serv. 1976;6(3):475–492. doi: 10.2190/E8NV-1RQJ-4RQA-7E2P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen M., Ware J. E., Jr, Donald C. A., Brook R. H. Measuring components of children's health status. Med Care. 1979 Sep;17(9):902–921. doi: 10.1097/00005650-197909000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson L. S. Crash involvement of teenaged drivers when driver education is eliminated from high school. Am J Public Health. 1980 Jun;70(6):599–603. doi: 10.2105/ajph.70.6.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro S., McCormick M. C., Starfield B. H., Krischer J. P., Bross D. Relevance of correlates of infant deaths for significant morbidity at 1 year of age. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1980 Feb 1;136(3):363–373. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(80)90863-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson R. W., White E. L. Changes in morbidity, disability, and utilization differentials between the poor and the nonpoor: data from the health interview survey: 1964 and 1973. Med Care. 1977 Aug;15(8):636–646. doi: 10.1097/00005650-197708000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]