Abstract

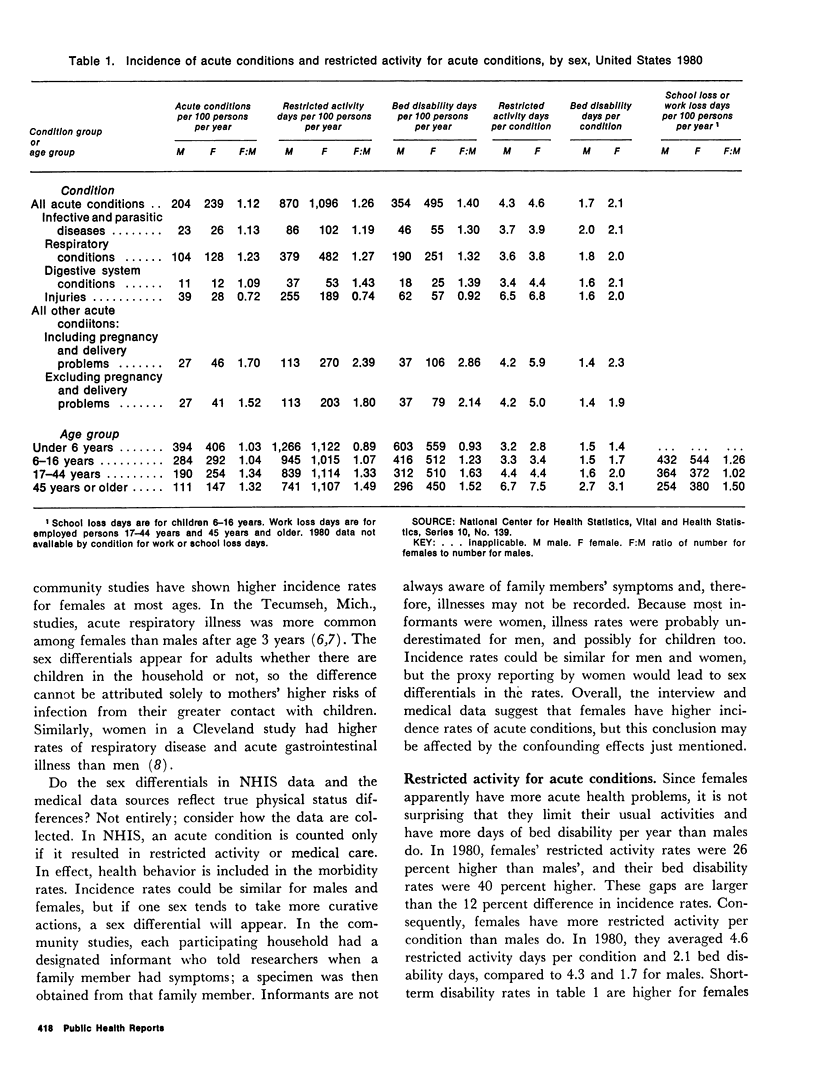

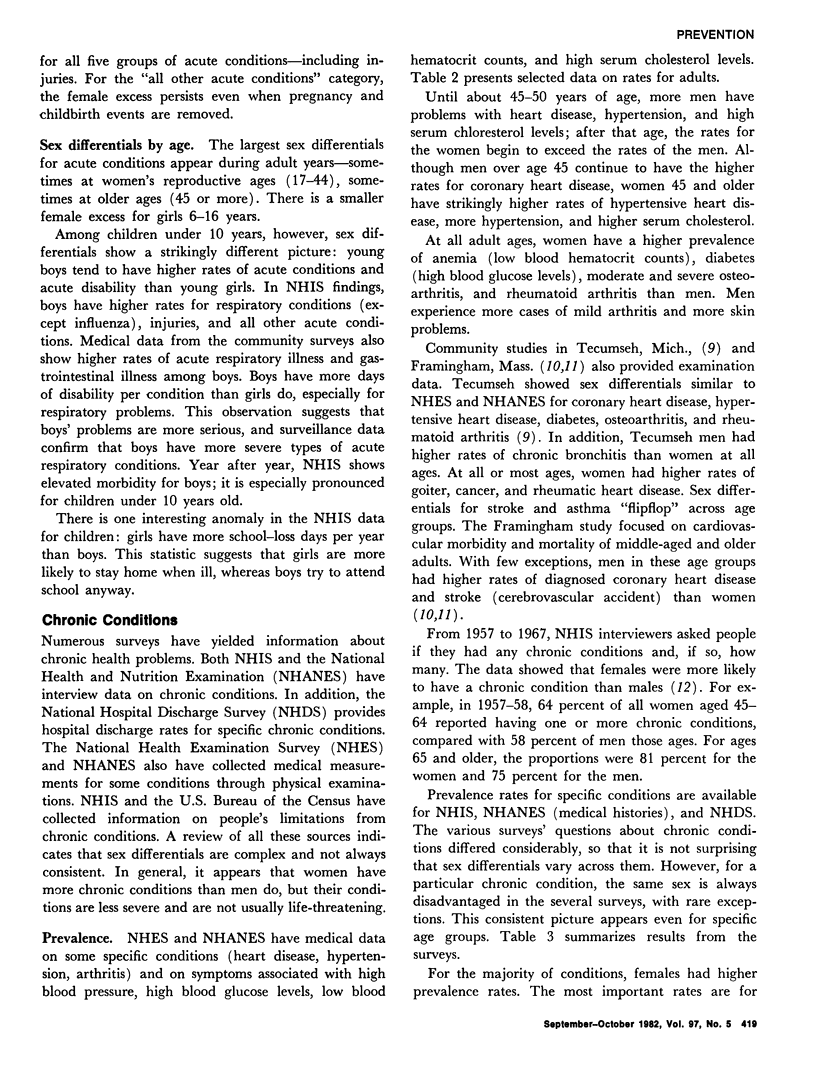

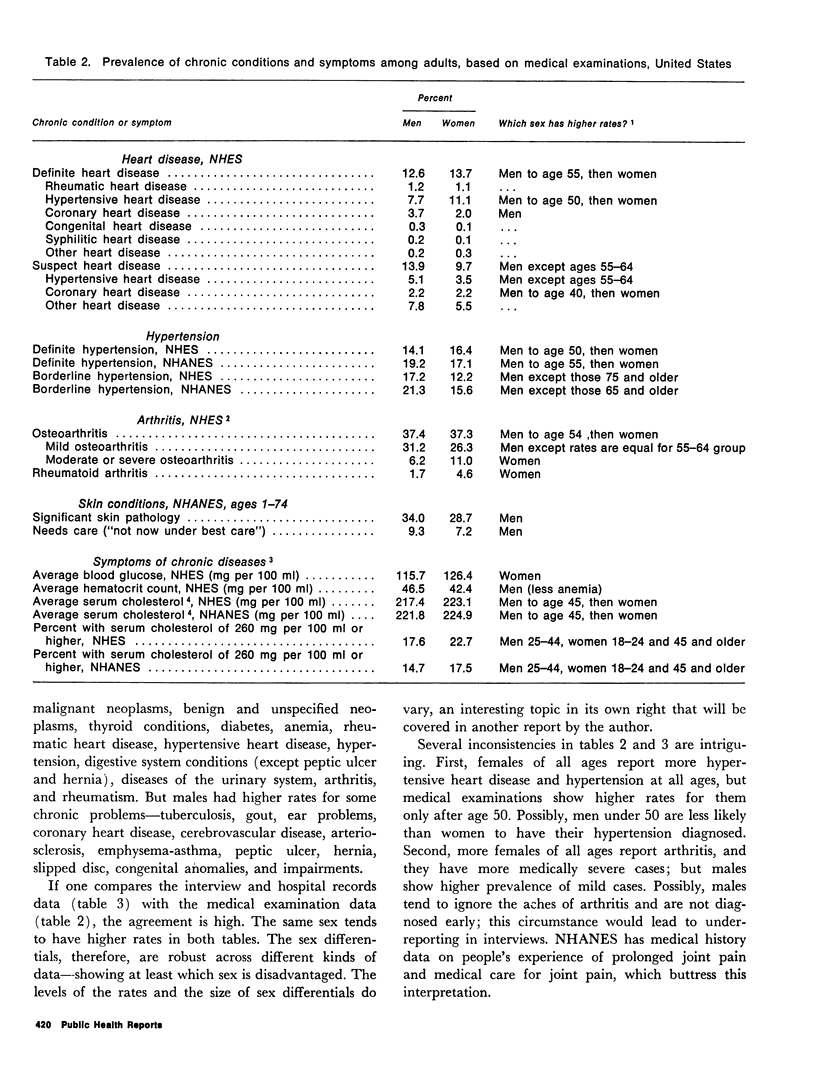

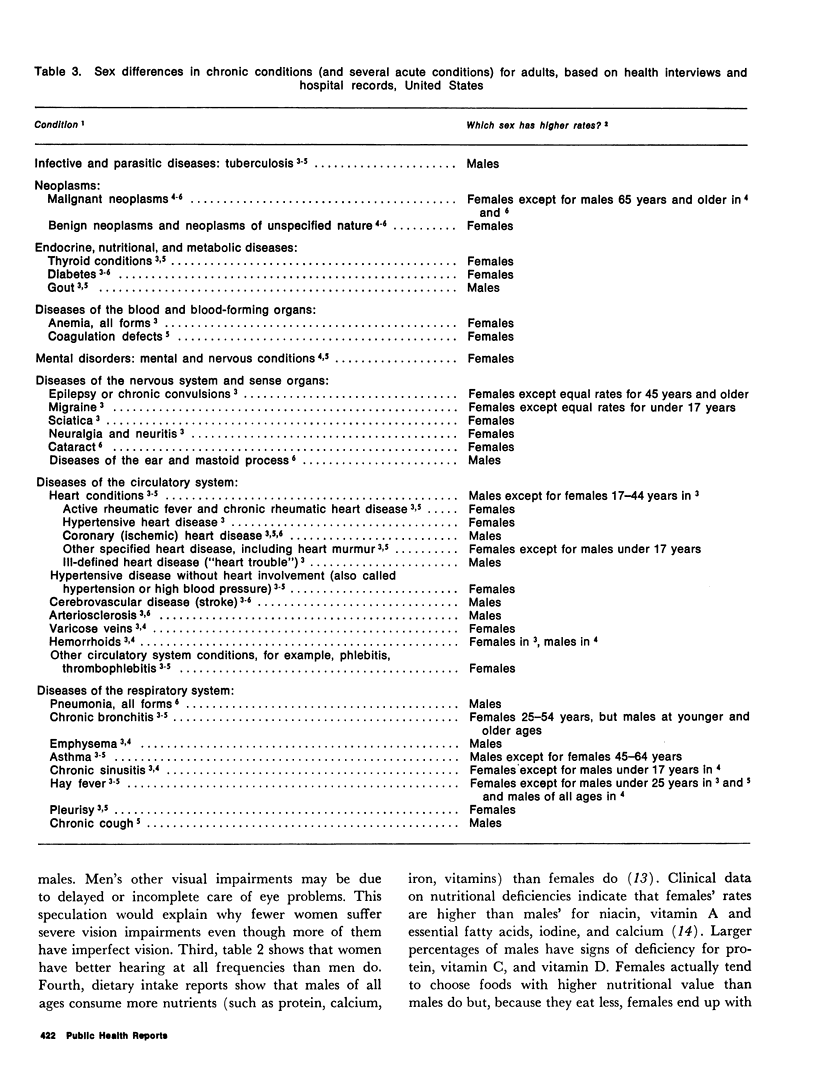

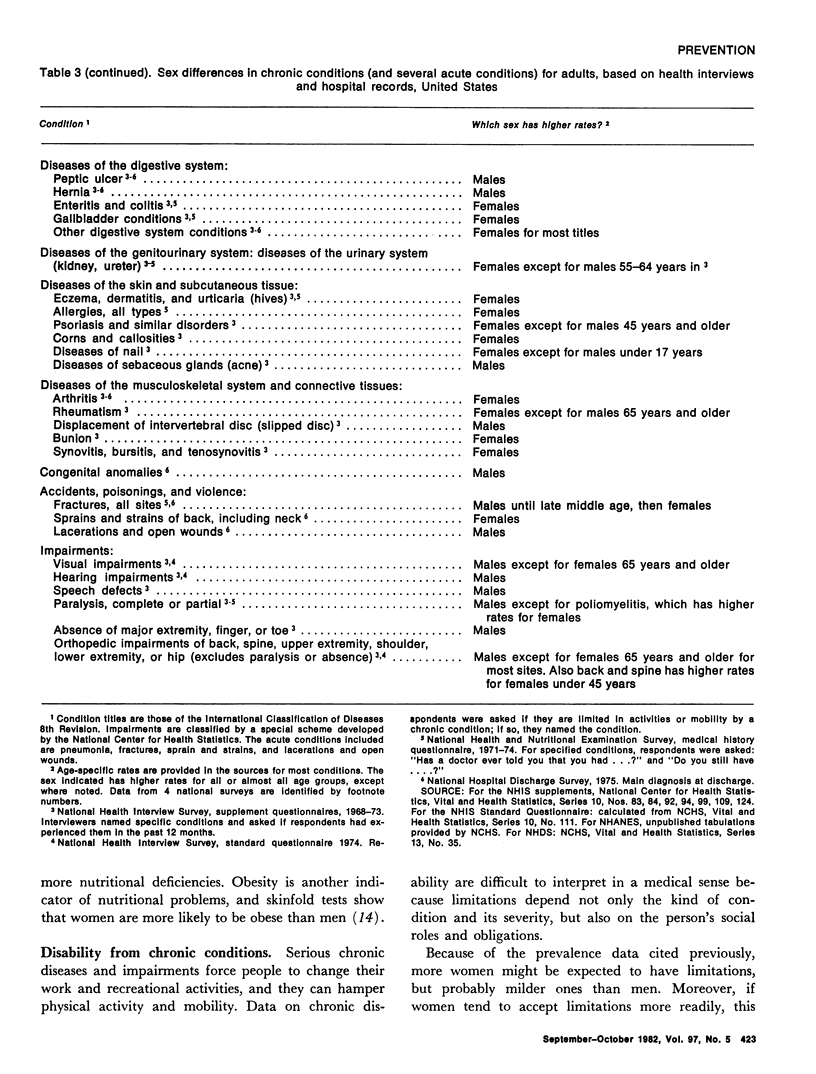

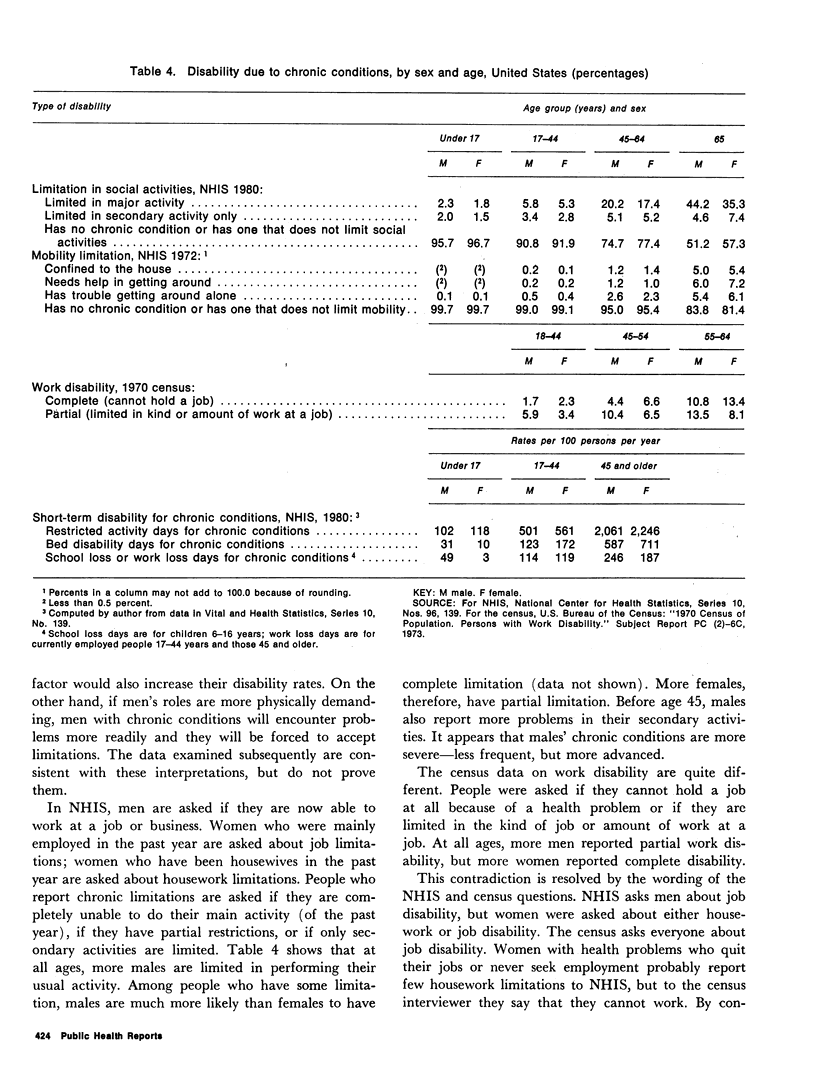

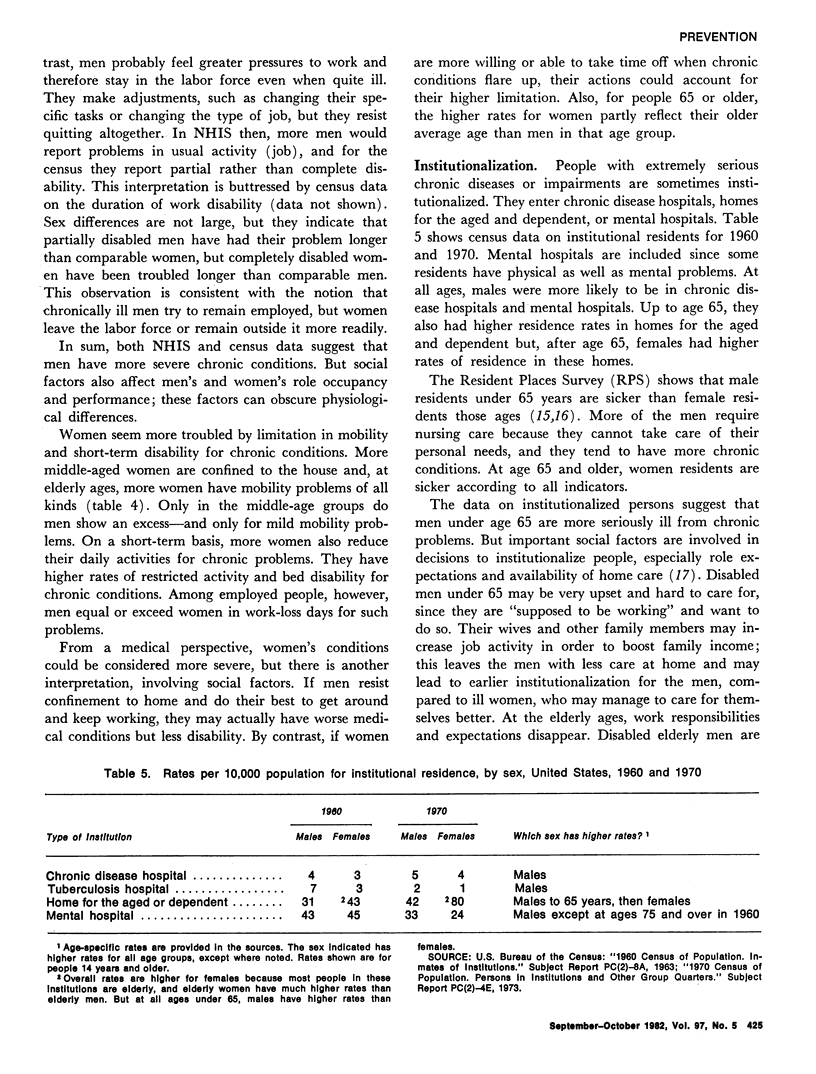

Health status and health behavior of males and females in the United States are compared; the data employed in the analysis are from community studies and the surveys of the National Center for Health Statistics. Females generally show a higher incidence of acute conditions, higher prevalence of minor chronic conditions, more short-term restricted activity, and more use of health services (especially outpatient services) and medicines. By contrast, males have higher prevalence rates for life-threatening chronic conditions, higher incidence of injuries, more long-term disability, and after about age 50, higher rates of hospitalization. These sex differences appear at all ages, except for early childhood when boys have a worse health profile than girls. The following interpretations are consistent with the data; they are hypotheses rather than demonstrated facts. Women are more frequently ill than men, but with relatively mild problems. By contrast, men feel ill less often, but their illnesses and injuries are more serious. These morbidity differences help to explain sex differentials in health behavior; frequent symptoms lead to more restricted activity, physician and dentist visits, and drug use for women; severe symptoms lead to more permanent limitations and hospitalization for men. But attitudes about symptoms, medical care, drugs, and self-care are also extremely important. Males may be socialized to ignore physical discomforts; thus, they are unaware of symptoms that females feel keenly. Also, men may be less willing and able to seek medical care for perceived symptoms. When diagnosis and treatment are finally obtained, men's conditions are probably more advanced and less amenable to control. Finally, men may be less willing and able to restrict their activities when ill or injured. Four important factors than underlie sex differentials in health are discussed: inherited risks of illness, acquired risks of illness and injury, illness and prevention orientations, and health reporting behavior. Statistics show that women ultimately have lower mortality rates than men--despite women's more frequent morbidity and possibly because of more care for their illnesses and injuries. The apparent contradiction between sex differences in morbidity and mortality (females are sicker but males die sooner) is explored.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Belloc N. B., Breslow L. Relationship of physical health status and health practices. Prev Med. 1972 Aug;1(3):409–421. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(72)90014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush P. J., Osterweis M. Pathways to medicine use. J Health Soc Behav. 1978 Jun;19(2):179–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush P. J., Rabin D. L. Who's using nonprescribed medicines? Med Care. 1976 Dec;14(12):1014–1023. doi: 10.1097/00005650-197612000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHILDS B. GENETIC ORIGIN OF SOME SEX DIFFERENCES AMONG HUMAN BEINGS. Pediatrics. 1965 May;35:798–812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter C. O. Sex differences in the distribution of physical illness in children. Soc Sci Med. 1978 Jul;12(3B):163–166. doi: 10.1016/0160-7987(78)90027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crandell D. L., Dohrenwend B. P. Some relations among psychiatric symptoms, organic illness, and social class. Am J Psychiatry. 1967 Jun;123(12):1527–1538. doi: 10.1176/ajp.123.12.1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EPSTEIN F. H., FRANCIS T., Jr, HAYNER N. S., JOHNSON B. C., KJELSBERG M. O., NAPIER J. A., OSTRANDER L. D., Jr, PAYNE M. W., DODGE H. J. PREVALENCE OF CHRONIC DISEASES AND DISTRIBUTION OF SELECTED PHYSIOLOGIC VARIABLES IN A TOTAL COMMUNITY, TECUMSEH, MICHIGAN. Am J Epidemiol. 1965 May;81:307–322. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MECHANIC D. THE INFLUENCE OF MOTHERS ON THEIR CHILDREN'S HEALTH ATTITUDES AND BEHAVIOR. Pediatrics. 1964 Mar;33:444–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MECHANIC D. The concept of illness behavior. J Chronic Dis. 1962 Feb;15:189–194. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(62)90068-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillen M. M. Differential mortality by sex in fetal and neonatal deaths. Science. 1979 Apr 6;204(4388):89–91. doi: 10.1126/science.571144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monto A. S., Ross H. Acute respiratory illness in the community: effect of family composition, smoking, and chronic symptoms. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1977 Jun;31(2):101–108. doi: 10.1136/jech.31.2.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monto A. S., Ullman B. M. Acute respiratory illness in an American community. The Tecumseh study. JAMA. 1974 Jan 14;227(2):164–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathanson C. A. Sex, illness, and medical care. A review of data, theory, and method. Soc Sci Med. 1977 Jan;11(1):13–25. doi: 10.1016/0037-7856(77)90141-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabin D. L., Bush P. J. Who's using medicines? J Community Health. 1975 Winter;1(2):106–117. doi: 10.1007/BF01319204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabkin J. G., Struening E. L. Live events, stress, and illness. Science. 1976 Dec 3;194(4269):1013–1020. doi: 10.1126/science.790570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson A. C., Kerr C. B. On the distribution of frequencies of mutation to genes determining harmful traits in man. Mutat Res. 1967 May-Jun;4(3):339–352. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(67)90029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suffet F., Brotman R. Female drug use: some observations. Int J Addict. 1976;11(1):19–33. doi: 10.3109/10826087109045527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbrugge L. M. Female illness rates and illness behavior: testing hypotheses about sex differences in health. Women Health. 1979 Spring;4(1):61–79. doi: 10.1300/J013v04n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbrugge L. M. Females and illness: recent trends in sex differences in the United States. J Health Soc Behav. 1976 Dec;17(4):387–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbrugge L. M. Sex differences in complaints and diagnoses. J Behav Med. 1980 Dec;3(4):327–355. doi: 10.1007/BF00845289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbrugge L. M. Sex differentials in morbidity and mortality in the United States. Soc Biol. 1976 Winter;23(4):275–296. doi: 10.1080/19485565.1976.9988243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbrugge L. M., Steiner R. P. Physician treatment of men and women patients: sex bias or appropriate care? Med Care. 1981 Jun;19(6):609–632. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198106000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WASHBURN T. C., MEDEARIS D. N., Jr, CHILDS B. SEX DIFFERENCES IN SUSCEPTIBILITY TO INFECTIONS. Pediatrics. 1965 Jan;35:57–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldron I. Why do women live longer than men? Soc Sci Med. 1976 Jul-Aug;10(7-8):349–362. doi: 10.1016/0037-7856(76)90090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallen J., Waitzkin H., Stoeckle J. D. Physician stereotypes about female health and illness: a study of patient's sex and the informative process during medical interviews. Women Health. 1979 Summer;4(2):135–146. doi: 10.1300/J013v04n02_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman M. M., Klerman G. L. Sex differences and the epidemiology of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1977 Jan;34(1):98–111. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1977.01770130100011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]