Abstract

Data indicates that millions of motor vehicles accidents (MVA) occur each year and that MVAs are one of the leading causes of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Despite these findings, PTSD screening tools have not been identified for MVA populations. The current study examines two potential PTSD screening tools, the Impact of Event Scale (IES) and the PTSD Symptom Scale, Self-Report (PSS-SR), in a large sample of MVA survivors. For the IES using a cutoff score of 27, sensitivity was .91, specificity was .72 and overall correct classification was .80. For the PSS-SR using a cutoff score of 14, sensitivity was .91, specificity was .62 and overall correct classification was .74. These data support the use of the IES and the PSS-SR as PTSD screening tools in MVA samples.

Keywords: PTSD, motor vehicle accident, screening, self-report measures, assessment

Screening for PTSD in motor vehicle accident survivors: The use of the PSS-SR and IES-R

According to the National Safety Council (1993), millions of motor vehicle accidents (MVAs) occur each year but only recently have the psychological consequences of MVAs been fully recognized. Norris (1992) has shed some light on the psychological sequela of MVAs by examining the frequency and impact of 10 potentially traumatic events in a large, multi-site epidemiological study. Among traumatized individuals in this study, MVAs were found to be a leading cause of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), preceded only by sexual and physical assaults. Moreover, Norris states that “when both the frequency and severity data were considered together, [MVAs] emerged as perhaps the single most significant event among those studied” (pp. 416). Extrapolating from the rates of trauma and PTSD, Norris estimates that MVAs alone could account for 28 cases of PTSD for every 1000 adults in the United States.

Other investigators have also examined the rates of PTSD and PTSD symptomatology in MVA populations. These investigations have produced a wide range of prevalence estimates depending on the methodology employed. For example, among consecutive admissions of MVA survivors at an emergency department, Mayou and colleagues found that 11% met criteria for PTSD in the following year (Mayou, Bryant & Duthie, 1993). In a similar study, 967 consecutive patients admitted to an emergency department following a MVA were assessed for PTSD at 3 months and at 1 year. A diagnosis of PTSD could be made in 23% of the sample at 3 months and 16.5% of the sample at 1 year (Ehlers, Mayou & Bryant, 1998). In contrast, 39% of MVA survivors who sought medical treatment for injuries sustained in a MVA met criteria for PTSD (Blanchard Hickling, Taylor & Loos, 1995) and 46% of individuals responding to advertisements for a MVA-related study met criteria for PTSD (Blanchard, Hickling, Taylor, Loos, & Gerardi, 1994). Due to the number of MVAs that occur in any given year and the rate of PTSD within MVA populations, MVA-related PTSD is a serious public health concern that warrants greater attention.

Given the high prevalence of MVA-related PTSD, tools are needed to identify individuals with this disorder in psychological/psychiatric settings, as well as in medical and chiropractic settings where MVA victims often receive treatment for physical complaints (e.g., Asmundson, Coons, Taylor, & Katz, 2002). As noted by Wohlfarth and colleagues (Wohlfarth, van den Brink, Winkel, & ter Smitten, 2003), a two-step approach to identifying PTSD has been recommended to improve efficiency in this effort (Shrout, Skodol, & Dohrenwend, 1986). In the first step, individuals are administered self-report measures relevant for a particular disorder. If a predetermined cutoff score is exceeded, a more extensive and time-consuming diagnostic evaluation can be conducted. By administering a self-report measure first to identify cases that are most likely to require additional assessment and possibly treatment, clinicians can efficiently allocate clinical services where they are potentially most needed or refer cases to other health care providers for appropriate clinical services. In the case of MVA survivors, the use of easy to administer self-report screening tools may help to identify individuals in both psychological and medical settings who are suffering serious psychological sequelae of a MVA and increase referrals to effective MVA-PTSD treatment (e.g., Blanchard & Hickling, 2004; Taylor & Koch, 1995). To date, empirically based cutoff scores for self-report measures of PTSD symptomatology have not been identified for MVA survivors.

In other populations at high risk for PTSD, psychometrically sound self-report measures have been used to screen for PTSD and cutoff scores have been developed for these populations. For example, Lang and colleagues (2003) recently reported on the utility of the PTSD Checklist (PCL-C; Weathers, Litz, Huska, & Keane, 1994) in screening for PTSD among female veterans in a primary care setting. Although the sample was small (n=49), these authors found that using a cutoff score of 29 provided sensitivity of .89, specificity of .68, and overall correct classification of .76 (Lang, Laffaye, Satz, Dresselhaus & Stein, 2003). Within a treatment seeking substance abuse population, a modified version of the PTSD Symptom Scale, Self Report (MPSS-SR; Falsetti, Resnick, Resick, & Kilpatrick, 1993) was used to identify individuals with PTSD (Coffey, Dansky, Falsetti, Saladin, & Brady, 1998). In this sample, the optimal cutoff score was identified as 28, which provided sensitivity of .89, specificity of .65, and overall correct classification of .74. Other investigators have examined the psychometric properties of the Impact of Event Scale - Revised (IES-R; Weiss & Marmar, 1997) in a sample of treatment seeking Vietnam veterans with PTSD and a sample of veterans from the community (Creamer, Bell, & Failla, 2003). Creamer et al. (2003), by using the recommended cutoff of 50 for the PTSD Checklist (Weathers, Litz, Herman, Huska, & Keane (1993) as the “diagnostic” standard, found that a cutoff score of 33 on the IES-R provided sensitivity of .91 and specificity of .82 in a community sample of veterans.

Most relevant to the current study, Wohlfarth and colleagues (2003) evaluated two widely used self-report measures of PTSD symptoms, the Impact of Event Scale (Horowitz, Wilner, & Alvarez, 1979) and the PTSD Symptom Scale - Self-report (PSS-SR; Foa, Riggs, Dancu, & Rothbaum, 1993) as potential screening measures, among a population of 79 male and female crime victims. These investigators found that the Dutch versions of both the IES (Brom & Kleber, 1985) and the PSS-SR (Arntz, 1993) performed well as PTSD screeners among crime victims regardless of whether DSM-IV or ICD-10 diagnostic criteria were used as the “gold standard” criterion. Using DSM-IV as the diagnostic criteria, a cutoff score of 35 on the IES total score produced sensitivity of .89, specificity of .94, and overall agreement of .94. Again, using DSM-IV criteria, the PSS-SR [scored to approximate a DSM-IV diagnosis rather than a total score; see Foa et al., (1993)], produced sensitivity of .90, specificity of .84, and overall agreement of .85 (Wohlfarth, van den Brink, Winkel & ter Smitten, 2003). Although these findings are encouraging, the results require cross-validation, primarily because of the relatively small sample that was employed.

The current study was designed to address gaps in the research literature and clinical practice by identifying empirically derived cutoff scores for the IES and PSS-SR for the identification of PTSD positive cases in clinical populations of MVA survivors. Specifically, this investigation attempts to support Wohlfarth et al.’s (2003) claim that the IES and PSS-SR perform well as PTSD screeners by replicating their findings in a larger, independent sample of treatment-seeking trauma victims.

Method

Participants

Participants included 159 women and 70 men (n=229) who had experienced a serious MVA at least one month before participation (mean time since MVA = 32.02 months, SD = 54.72) and were seeking professional help. In order to determine if the MVA met Criterion A for PTSD (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), participants were asked to rate feelings of fear, helplessness, danger and perceptions that they might die during the accident using 0-100 scales (where 0 = ‘not at all’ and 100 = ‘extreme’; Blanchard & Hickling, 2004). Participants needed to provide ratings at or above 50 on fear or helplessness (mean fear = 75.96, SD = 33.03; mean helplessness = 82.16, SD = 29.08) and a rating at or above 50 on perceptions of danger or that they might die (mean danger = 72.78, SD = 35.19; mean fear of dying = 34.81, SD = 40.61). All participants were between 18 and 79 years of age (mean age = 41.0 yrs., SD = 12.4). Within the sample, 193 (84%) were Caucasian, 25 (11%) were African American, and 11 (5%) were of another ethnicity. Most participants (69%) were suffering from pain, which was the result of injuries sustained during the MVA. For an individual to be described as having chronic pain, significant lifestyle limitations and distress had to be reported and the individual had to be seeking medical care (e.g., prescription pain medication, physical therapy, chiropractic care, etc.) for their pain. Individuals with pain complaints tended to report musculoskeletal or soft tissue injury (80% of the pain sub-sample) and to have experienced pain for at least 3 months (68% of the pain sub-sample).

Participants were selected from a pool of 241 individuals. As recommended by Tabachnick and Fidell (1996), univariate outliers (n=8) were removed. In addition, four participants were excluded due to significant head injuries from the MVA. Participants were referred to the project by primary care physicians, physical therapists, chiropractors, massage therapists, a university pain service and specialists in rehabilitation and internal medicine as well as by the use of flyers distributed in community centers and at the local Department of Motor Vehicles. Demographic information on the sample is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and Axis I diagnoses for the sample. Unless otherwise noted, the number of cases for each cell is provided followed by the associated percent of sample value (in parentheses).

| PTSD Positive (n = 99) | PTSD Negative (n = 130) | Total (n = 229) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) | 42.0 (10.0) | 40.3 (13.9) | 41.0 (12.4) |

| Gender (%) | |||

| Female | 72 (73) | 87 (67) | 159 (69) |

| Race (%) | |||

| White | 78 (79) | 115 (89) | 193 (84) |

| Black | 17 (17) | 8 (6) | 25 (11) |

| Hispanic | 4 (4) | 3 (2) | 7 (3) |

| Other races | -- | 4 (3) | 4 (2) |

| Marital status (%) | |||

| Married/cohabitating | 56 (57) | 58 (45) | 114 (50) |

| Single | 22 (22) | 48 (37) | 70 (30) |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 21 (21) | 24 (18) | 45 (20) |

| Education (%) | |||

| Grades 1-8 | 1 (1) | -- | 1 (.4) |

| Grades 9-12 | 23 (23) | 14 (11) | 37 (16) |

| College, less than bachelors | 52 (53) | 53 (41) | 105 (46) |

| Four-year degree | 13 (13) | 30 (23) | 43 (19) |

| Above four-year degree | 10 (10) | 33 (25) | 43 (19) |

| Employment (%) | |||

| Full-time | 34 (34) | 54 (42) | 88 (38) |

| Part-time | 12 (12) | 28 (21) | 40 (18) |

| Homemaker | 7 (7) | 6 (5) | 13 (6) |

| Unemployed | 43 (43) | 42 (32) | 85 (37) |

| Missing | 3 (3) | -- | 3 (1) |

| Comorbid Axis I Disorders (%)a | |||

| Panic with and without agoraphobia | 19 (19) | 7 (5) | 26 (11) |

| Social Phobia | 11 (11) | 15 (12) | 26 (11) |

| Generalized Anxiety | 40 (40) | 23 (18) | 63 (28) |

| Specific Phobia | 30 (30) | 25 (19) | 55 (24) |

| Obsessive-Compulsive | 10 (10) | 3 (2) | 13 (6) |

| Major Depression | 42 (42) | 13 (10) | 55 (24) |

| Dysthymia | 6 (6) | 5 (4) | 11 (5) |

| Bipolar | 4 (4) | 1 (1) | 5 (2) |

| Hypochondriasis or Somatization | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) |

| Alcohol Abuse or Dependence | 6 (6) | 7 (5) | 13 (6) |

| Drug Abuse or Dependence | 4 (4) | 4 (3) | 8 (3) |

Participants could meet diagnostic criteria for multiple comorbid psychiatric conditions.

Measures

PTSD measures. Two self-report measures were examined in this study, the PTSD Symptom Scale - Self Report (PSS-SR; Foa et al., 1993) and the Impact of Event Scale (IES; Horowitz et al., 1979). The PSS-SR contains 17 items, reflecting the DSM-IV symptoms of PTSD, which are rated on a 3-point Likert scale, ranging from “not at all” to “5 or more times/week - almost always”. The highest possible score on the PSS-SR is 51. Foa et al. (1993) evaluated the psychometric properties of the PSS-SR with 46 female rape victims and 72 female non-sexual assault victims, noting that the scale showed high internal consistency (α = .91) and good one-month test-retest reliability (r = .74). Convergent validity of the PSS-SR, with the IES and State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Spielberger, Gorsuch, & Lushene, 1970) also was demonstrated, with correlations ranging from .52 to .81 (Foa et al., 1993). Items on the PSS-SR were summed to produce a total score. In the current sample, internal consistency, as indexed by Cronbach’s coefficient (α) was .94.

The IES contains 15 items that are distributed across two subscales, which assess intrusion (7 items) and avoidance (8 items). The frequency of each item is rated on a 4-point scale: 0 (not at all), 1 (rarely), 3 (sometimes), or 5 (often). The highest possible total score on the IES is 75. The IES has been shown to have high internal consistency with alpha coefficients of .78 for the intrusion subscale and .82 for the avoidance subscale in a sample of 66 outpatients (Horowitz et al., 1979). Split-half reliability of the total scale was .86 and the one-week test-retest reliability was .89 for the intrusion subscale and .79 for the avoidance subscale (Horowitz et al., 1979). Items on the IES were summed to produce a total score. In the current sample, internal consistency, as measured by Cronbach’s coefficient (α) was .86.

Current PTSD was diagnosed using the Clinical Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS; Blake et al., 1995). The CAPS is a structured interview that assesses the 17 symptoms of PTSD identified in the current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association, 2000). The CAPS includes standardized questions to determine the frequency and intensity of PTSD symptoms in the preceding month, using a 5-point Likert scale (e.g., 0 indicates that the symptom does not occur or does not cause distress and 4 indicates that the symptom occurs nearly every day or causes extreme distress and discomfort). The CAPS also includes standardized questions assessing subjective distress and impairment in social and occupational functioning due to these problems. Probes were added to the interview to determine whether each symptom was attributable to chronic pain1. The CAPS has strong psychometric properties (e.g., Weathers, Keane, & Davidson, 2001) and has been shown to be sensitive to the detection of PTSD in individuals following a MVA (Blanchard et al., 1996).

The CAPS was administered by trained clinicians who were advanced doctoral students in clinical and counseling psychology. All clinicians received extensive training in the use of the CAPS. All interviews were videotaped and 30% were randomly selected to be reviewed by a second clinician to establish reliability. Inter-diagnostician agreement in PTSD diagnosis, reflected by the kappa statistic, was strong (k = .94).

Anxiety and depressive disorder measures. In order to evaluate the presence of other anxiety disorders, the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule (ADIS-IV; DiNardo, Brown, & Barlow, 1994) was administered. The ADIS-IV is a semi-structured interview designed to evaluate the presence and severity of each of the anxiety disorders (Panic Disorder, Agoraphobia, Social Phobia, Specific Phobia, Generalized Anxiety Disorder, and Obsessive Compulsive Disorder). The same clinicians who administered the CAPS also administered the ADIS-IV. All interviewers received extensive training in use of the ADIS-IV, following procedures outlined by DiNardo, Moras, Barlow, Rapee, and Brown (1993). As with the CAPS, 30% were reviewed by a second clinician to establish reliability. Inter-diagnostician agreement was assessed using the kappa statistic. Agreement between diagnosticians was strong for Social Phobia (k = .74), Panic Disorder with (k = 0.82) and without Agoraphobia (k = 1.00), and Generalized Anxiety Disorder (k = 0. 91), and moderate for Specific Phobia (k = 0.75) and Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (k = 0.58). Use of the ADIS-IV is widespread in research on the anxiety disorders and this interview is recognized as providing reliable and valid diagnoses (Brown, DiNardo, Lehman, & Campbell, 2001). The frequencies of anxiety disorders present in the sample are presented in Table 1.

The ADIS-IV also was used to evaluate the presence of mood disorders (Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), Dysthymic Disorder and Bipolar Disorder). Diagnostic reliability, established as previously described, was strong for MDD (k = 0.85) and Bipolar Disorder (k = 0.85)2. The frequencies of mood disorders in the sample are presented in Table 1.

Procedure

All procedures were reviewed by the University at Buffalo - SUNY Institutional Review Board. After providing informed consent, the CAPS and the ADIS-IV were administered to the individual. Each participant returned for a second appointment and completed a self-report battery that included the PSS-SR and the IES.

Analytic strategy

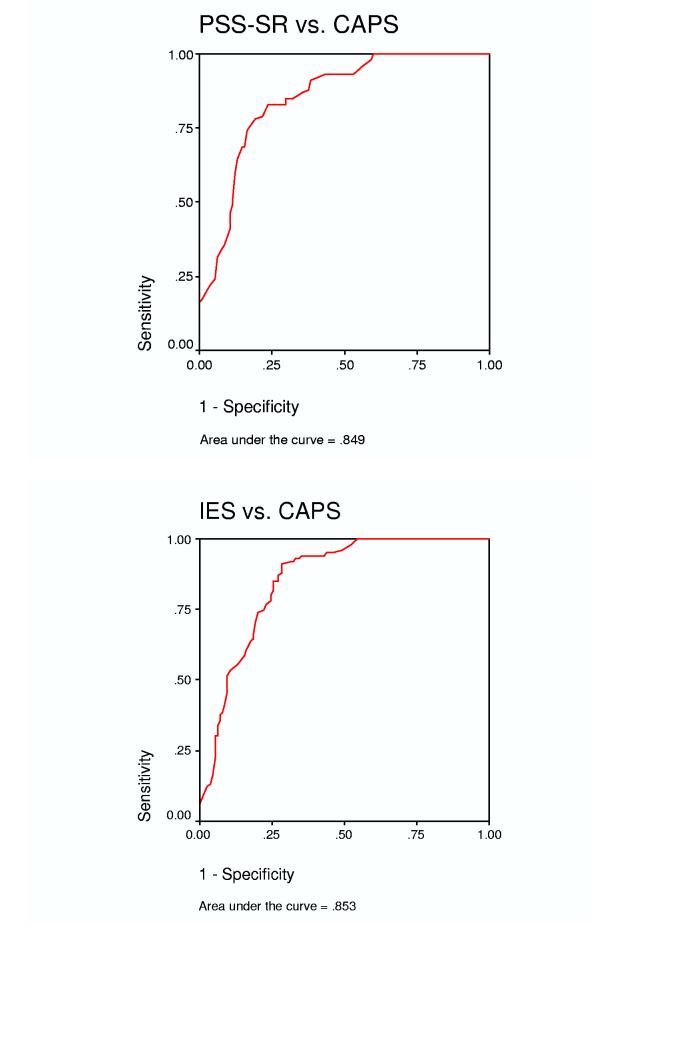

Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curves were used to identify the cutoff scores for the PSS-SR and IES that would optimally balance sensitivity and specificity in identifying PTSD positive cases. ROC curves plot sensitivity on the y-axis and 1 - specificity on the x-axis for each possible cutoff score of a predictor (i.e., PSS-SR, IES). The overall accuracy of the predictor is characterized by the area under the curve (AUC) statistic, which can vary from .5 to 1.0. An AUC of .5 indicates chance prediction while an AUC of 1.0 signifies perfect prediction. The relationship between the categorical variable of self-report measures of PTSD symptomatology (i.e., the PSS-SR, IES) at the optimal cutoff score for each predictor and the categorical interview measure of PTSD (i.e., CAPS diagnosis of PTSD) was assessed through 2 × 2 tables. Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative prediction, false positive and negative rates, overall correct classification rates, and kappa statistics were calculated from data in the 2 × 2 tables (see Kessel & Zimmerman, 1993).

Results

Using the CAPS as a diagnostic tool for PTSD, 43% (n = 99) met criteria for current PTSD stemming from a MVA. No differences were found between male and female participants on the prevalence of PTSD, χ2(1)=.89, ns, or on the severity of their PTSD symptoms as measured by the CAPS total score, F(1,227)=2.07, ns.

PTSD Classification Analysis Using the PSS-SR

The relation between PTSD status diagnosed via the CAPS and the PSS-SR was examined using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, to identify the optimal cutoff score. The top panel of Figure 1 represents the ROC curve for all available values of the PSS-SR when the CAPS PTSD diagnosis is used as a dichotomous variable. For the PSS-SR, the value for the AUC (.85) indicates that the questionnaire is quite accurate in identifying PTSD positive cases. A range of cutoff scores for the PSS-SR, along with corresponding sensitivity, specificity, overall correct classification rates, and kappa statistics are presented in Table 2. Table 2 represents sensitivity indices ranging from 1.00 (perfect sensitivity) to .80 sensitivity. To capture the greatest number of PTSD positive cases without unduly sacrificing specificity, a target of approximately .90 sensitivity was selected a priori (see Coffey et al., 1998). Table 2 reveals that a cutoff score of 14 produces sensitivity of .91 and provides the greatest specificity among cutoff scores associated with approximately .90 sensitivity. Using a PSS-SR Total Score of 14 as a cutoff, the PSS-SR was able to correctly classify 90 of the 99 PTSD positive patients for a sensitivity rate of 91%, a specificity rate of 62%, and an overall correct classification rate of 74%. The results of this classification analysis are presented in Table 3.

Figure 1.

Receiver operating curves depicting the ability of the PTSD Symptom Scale - Self Report (PSS-SR) and the Impact of Event Scale (IES) to correctly identify PTSD as measured by Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS).

Table 2.

Sensitivity, specificity, overall correct classification, and kappa values for various cutoff points for the PTSD Symptom Scale - Self Report (PSS-SR).

| Cutoff | Sensitivity | Specificity | Overall Correct | Kappa (α) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 1.00 | .40 | .66 | .37 |

| 9 | .98 | .41 | .66 | .36 |

| 10 | .96 | .44 | .66 | .37 |

| 11 | .93 | .47 | .67 | .37 |

| 12 | .93 | .55 | .71 | .45 |

| 13 | .93 | .57 | .72 | .47 |

| 14 | .91 | .62 | .74 | .50 |

| 15 | .88 | .62 | .73 | .48 |

| 16 | .87 | .65 | .74 | .50 |

| 17 | .85 | .68 | .75 | .51 |

| 18 | .85 | .70 | .76 | .53 |

| 19 | .83 | .70 | .76 | .52 |

| 20 | .83 | .76 | .79 | .58 |

| 21 | .79 | .78 | .79 | .57 |

Table 3.

PTSD Symptom Scale - Self Report (PSS-SR) classification analysis employing a cut off score of 14.

| CAPS PTSD Diagnosis |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present | Absent | Total | ||

| Positive | 90 | 50 | 140 | |

| PSS-SR | Negative | 9 | 80 | 89 |

| Total | 99 | 130 | 229 | |

Sensitivity = 91%

Specificity = 62%

Positive Predictive Power = 64%

Negative Predictive Power = 90%

False Positive Rate = 38%

False Negative Rate = 9%

Overall Correct Classification = 74%

Kappa = .50 (p < .001)

In order to examine whether gender influenced this cutoff score, these analyses were repeated separately for men and women. For female participants, the PSS-SR was able to correctly classify 64 of the 72 PTSD positive patients for a sensitivity rate of 90%, a specificity rate of 62%, and an overall correct classification rate of 74%. For male participants, the PSS-SR was able to correctly classify 26 of the 27 PTSD positive patients for a sensitivity rate of 96%, a specificity rate of 61%, and an overall correct classification rate of 74%.

To examine the effects of self reported chronic pain on correct classification of individuals with and without PTSD using this cutoff score (14), these analyses were repeated separately for participants with and without chronic pain. For individuals with pain, the PSS-SR was able to correctly classify 80 of the 87 PTSD positive patients for a sensitivity rate of 92%, a specificity rate of 48%, and an overall correct classification rate of 72%. For individuals without self-reported chronic pain, the PSS-SR was able to correctly classify 10 of the 12 PTSD positive patients for a sensitivity rate of 83%, a specificity rate of 78%, and an overall correct classification rate of 79%.

PTSD Classification Analysis Using the IES

The relation between PTSD status diagnosed via the CAPS and the IES was also examined using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. The bottom panel of Figure 1 represents the ROC curve for all available values of the IES when the CAPS PTSD diagnosis is used as a dichotomous variable. Just as with the PSS-SR, the AUC for the IES is .85, which indicates that the measure also is quite accurate in identifying PTSD positive cases. A range of cutoff scores for the IES, along with corresponding sensitivity, specificity, overall correct classification rates, and kappa statistics are presented in Table 4. As with the PSS-SR, cutoff scores are provided within the sensitivity range of 1.00 to .80. Again, a .90 sensitivity value was targeted to capture the greatest number of PTSD positive cases while maintaining a reasonable level of false positives. Using .90 as a criterion, a cutoff score of 27 for the IES Total Score was selected as optimal. Using this score as a cutoff, the IES was able to correctly classify 90 of the 99 PTSD positive patients for a sensitivity rate of 91%, a specificity rate of 72%, and an overall correct classification rate of 80%. The results of this classification analysis are presented in Table 5.

Table 4.

Sensitivity, specificity, overall correct classification, and kappa values for various cutoff points for the Impact of Event Scale (IES).

| Cutoff | Sensitivity | Specificity | Overall Correct | Kappa (α) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | 1.00 | .45 | .69 | .42 |

| 13 | .98 | .48 | .69 | .42 |

| 14 | .96 | .51 | .70 | .44 |

| 15 | .95 | .54 | .72 | .46 |

| 16 | .95 | .56 | .73 | .48 |

| 17 | .94 | .57 | .73 | .48 |

| 18 | .94 | .59 | .74 | .50 |

| 19 | .94 | .61 | .75 | .52 |

| 20 | .94 | .62 | .76 | .54 |

| 21 | .94 | .65 | .77 | .56 |

| 22 | .93 | .65 | .77 | .56 |

| 23 | .93 | .67 | .78 | .57 |

| 24 | .92 | .68 | .78 | .57 |

| 25 | .92 | .68 | .79 | .53 |

| 26 | .91 | .72 | .80 | .60 |

| 27 | .91 | .72 | .80 | .60 |

| 28 | .88 | .72 | .79 | .58 |

| 29 | .87 | .73 | .79 | .58 |

| 30 | .85 | .73 | .78 | .57 |

| 31 | .85 | .75 | .79 | .58 |

| 32 | .82 | .75 | .78 | .55 |

| 33 | .80 | .75 | .77 | .54 |

Table 5.

Impact of Event Scale (IES) classification analysis employing a cut off score of 27.

| CAPS PTSD Diagnosis |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present | Absent | Total | ||

| Positive | 90 | 37 | 127 | |

| IES | Negative | 9 | 93 | 102 |

| Total | 99 | 130 | 229 | |

Sensitivity = 91%

Specificity = 72%

Positive Predictive Power = 71%

Negative Predictive Power = 91%

False Positive Rate = 28%

False Negative Rate = 9%

Overall Correct Classification = 80%

Kappa = .60 (p < .001)

Similar to the analysis for the PSS-SR, classification of individuals with and without PTSD was examined as a function of gender using the IES. Using a cut off score of 27, the IES was able to correctly classify 64 of the 72 female PTSD positive patients for a sensitivity rate of 90%, a specificity rate of 67%, and an overall correct classification rate of 77%. For male participants, the IES was able to correctly classify 26 of the 27 PTSD positive patients for a sensitivity rate of 96%, a specificity rate of 81%, and an overall correct classification rate of 87%.

Likewise, these analyses were repeated to examine the effect of pain status on the IES cutoff score. For individuals with chronic pain, the IES was able to correctly classify 79 of the 87 PTSD positive patients for a sensitivity rate of 91%, a specificity rate of 62%, and an overall correct classification rate of 78%. For individuals without chronic pain, the IES was able to correctly classify 11 of the 12 PTSD positive patients for a sensitivity rate of 92%, a specificity rate of 83%, and an overall correct classification rate of 85%.

Discussion

The results from this study provides further evidence that the IES and the PSS-SR can be used to screen for PTSD among individuals who are at high risk for meeting diagnostic criteria for PTSD among treatment-seeking samples. Both the IES and the PSS-SR proved to be effective screeners for PTSD in this MVA survivor sample. In this study, .90 was selected a priori for each measure’s target sensitivity. It has been argued previously (Coffey et al., 1998; Lang et al., 2003; Wohlfarth et al., 2003), that approximately .90 is an appropriate sensitivity level for a screening tool when the primary goal is to reduce the incidence of false negatives (i.e., cases of true PTSD missed by the screening tool). With psychiatric screening tools, the incidences of false positives are less of a concern since the initial screen will be followed by a thorough diagnostic interview. With the goal of reducing false negatives, both measures were quite capable of identifying PTSD positive cases while maintaining an acceptable rate of false negative cases. Comparing the two measures, the PSS-SR, using a cutoff score of 14, and the IES, using a cutoff score of 27, were able to identify 90 out of 99 PTSD positive cases for a sensitivity rate of .91. However, the specificity of the IES (.72) was somewhat better than the specificity produced by the PSS-SR (.62). Likewise, the overall correct classification was higher for the IES than the PSS-SR, .80 and .74, respectively.

To examine the stability of the PTSD screening tools within subpopulations of MVA survivors, PTSD classification by the IES and the PSS-SR was examined as a function of pain status. Due to the nature of MVAs and the injuries often associated with them, chronic pain is a common complaint among individuals seeking psychological treatment following MVAs. Therefore, it is important to examine if classification efficiency varies as a function of pain status in MVA survivors. The optimal cutoff scores for the PSS-SR and the IES in the total sample, 14 and 27 respectively, was used to examine the measures’ efficiency in classifying individuals as either PTSD positive or PTSD negative for individual with or without chronic pain. In general, PTSD classification efficiency did not differ for either measure as a function of chronic pain status. For the PSS-SR, sensitivity in classifying PTSD in MVA survivors without chronic pain was somewhat lower compared to individuals with chronic pain (.83 and .92, respectively) In interpreting this finding, it is important to note that the low number of PTSD positive cases could have played a role. In the non-pain group, only 12 participants met criteria for PTSD and the PSS-SR was able to correctly classify 10 of them. By way of comparison, the IES was able to correctly identify 11 of these 12 cases. Due to the small number of PTSD positive cases in the non-pain group, these results are potentially unstable. Continued work on the influence of pain on PTSD screening measures, such as the IES and the PSS-SR, may prove beneficial.

Similar to the analysis for pain status, the optimal cutoff scores identified for the IES and PSS-SR were examined as a function of gender. Using the optimal cutoff scores for each measure, both the IES and PSS-SR were able to identify 64 of 72 female PTSD positive cases and 26 of 27 male PTSD positive cases. Specificity and overall correct classification were acceptable for both genders using both screening tools. Therefore, it is recommended that the full sample optimal cutoff scores identified for the IES and PSS-SR be used irrespective of gender.

In this study, while both the IES and the PSS-SR perform admirably as PTSD screeners in this MVA survivor sample, the optimal cutoff score for the IES differed somewhat from scores identified in previous published reports. Most relevant to this study, Wohlfarth et al. (2003) found that when using DSM-IV criteria, the optimal cutoff score for the IES associated with .89 sensitivity was 39, considerably higher than the optimal cutoff score of 27 identified in this sample of MVA survivors. In contrast, the optimal cutoff score (sensitivity of .90) reported in Wohlfarth et al. for the PSS-SR was 15, a score consistent with the optimal cutoff score of 14 identified in the current sample. It is possible that differences between the samples and instruments may account for the dissimilar PSS-SR cutoff scores reported in Wohlfarth et al. and the current study. One difference between the studies is that Wohlfarth et al. used the Dutch versions of the IES rather than the original English version. These authors also relied on the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI; World Health Organization, 1997) to determine diagnostic status, which was administered by telephone by third year psychology students. These methodological differences, as well as differences in language, may partially account for the discrepant findings. In addition, Wohlfarth et al. used a sample of violent crime victims recruited from local police stations while the current study used a sample of treatment seeking MVA survivors who had experienced their target trauma much longer before the assessment. These sample differences also may partially account for the inconsistencies between the two studies. Lastly, the sample used by Wohlfarth et al. was approximately one-half the size of the sample used in this study. It is possible that the smaller sample may have produced a spuriously high cutoff score on the IES.

In summary, this study provides further evidence that the IES and the PSS-SR can be used efficiently as PTSD screeners in high-risk samples. Both measures have good specificity and overall correct classification when the sensitivity criterion is set at approximately .90. Both measures are brief and each requires only 5-10 minutes to complete, making them ideal measures to administer in clinics frequented by MVA survivors for medical treatment following their MVA (e.g., family medicine, internal medicine, physical therapy, chiropractic clinics, etc.), clinics where mental health professionals are typically not available. In settings such as these, use of either the PSS-SR or the IES as PTSD screening tools may substantially increase the number of MVA survivors who are referred for, and who may ultimately benefit from, PTSD treatment.

Footnotes

For example, if a patient reported difficulty sleeping, the clinician assessed whether this symptom was due to pain. If so, the symptom was not scored on the CAPS.

There were not enough cases to calculate kappa statistic for Dysthymic Disorder.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. text revision Author; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Arntz A. Dutch translation of the PSS-SR. Author; Maastricht, the Netherlands: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Asmundson GJ, Coons MJ, Taylor S, Katz J. PTSD and the experience of pain: Research and clinical implications of shared vulnerability and mutual maintenance models. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry - Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie. 2002;47:930–937. doi: 10.1177/070674370204701004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Gusman FD, Charney DS, Keane TM. The development of a Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1995;8:75–90. doi: 10.1007/BF02105408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard EB, Hickling EJ. After the Crash. 2nd ed. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard E, Hickling E, Taylor A, Loos W. Psychiatric morbidity associated with motor vehicle accidents. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1995;183:495–504. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199508000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard EB, Hickling EJ, Taylor AE, Loos WR, Gerardi RJ. Psychological morbidity associated with motor vehicle accidents. Behavior Research and Therapy. 1994;32:283–290. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)90123-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard EB, Hickling EJ, Taylor AE, Loos WR, Fornere CA, Jaccard J. Who develops PTSD from motor vehicle accidents? Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1996;34:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(95)00058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brom D, Kleber RJ. De schok verwerking lijst [The impact of event questionnaire] Netherlands Tijdschrift voor de Psychologie. 1985;40:164–234. [Google Scholar]

- Brown T, DiNardo P, Lehman C, Campbell L. Reliability of DSM-VI anxiety and mood disorder: Implications for the classification of emotional disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:49–58. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey SF, Dansky BS, Falsetti SA, Saladin ME, Brady KT. Screening for PTSD in a substance abuse sample: Psychometric properties of a modified version of the PTSD Symptom Scale Self-Report. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1998;11:393–399. doi: 10.1023/A:1024467507565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creamer M, Bell R, Failla S. Psychometric properties of the Impact of Event Scale-Revised. Behaviour Research & Therapy. 2003;41:1489–1496. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiNardo P, Brown T, Barlow D. Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV. Greywind; Albany, NY: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- DiNardo P, Moras K, Barlow D, Rapee R, Brown T. Reliability of DSM-III-R anxiety disorder category. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1993;50:251–256. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820160009001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers A, Mayou RA, Bryant B. Psychological predictors of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder after motor vehicle accidents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:508–519. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.3.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falsetti SA, Resnick HS, Resick PA, Kilpatrick DG. The modified PTSD Symptom Scale: A brief self-report measure of posttraumatic stress disorder. the Behavior Therapist. 1993;16:161–162. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Riggs DS, Dancu CV, Rothbaum BO. Reliability and validity of a brief instrument for assessing post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1993;6:459–473. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz MJ, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of event scale: A measure of subjective stress. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1979;41:209–218. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197905000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessel JB, Zimmerman M. Reporting errors in studies of the diagnostic performance of self-administered questionnaires: Extent of the problem, recommendations for standardized presentation of results, and implications for the peer review process. Psychological Assessment. 1993;5:395–399. [Google Scholar]

- Lang AJ, Laffaye C, Satz LE, Dresselhaus TR, Stein MB. Sensitivity and specificity of the PTSD Checklist in detecting PTSD in female veterans in primary care. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2003;16:257–264. doi: 10.1023/A:1023796007788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayou R, Bryant B, Duthie R. Psychiatric consequences of road traffic accidents. British Medical Journal. 1993;307:647–651. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6905.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Safety Council The national accident fatality toll. Traffic Safety. 1993;93:15. [Google Scholar]

- Norris F. Epidemiology of trauma: Frequency and impact of different potentially traumatic events on different demographic groups. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60:409–418. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.3.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Skodol AE, Dohrenwend BP. A two-stage approach for case identification and diagnosis, first stage instruments. In: Barrett JE, Rose RM, editors. Mental disorders in the community: Progress and challenge. Guildford Press; New York: 1986. pp. 286–303. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE. State trait anxiety inventory. Consulting Psychologists Press; Palo Alto, CA: 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. 3rd Ed. HarperCollins; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S, Koch WJ. Anxiety disorders due to motor vehicle accidents: Nature and treatment. Clinical Psychology Review. 1995;15:721–738. [Google Scholar]

- Weathers F, Keane TW, Davidson JRT. Clinical-administered PTSD scale: A review of the first ten years of research. Depression and Anxiety. 2001;13:132–156. doi: 10.1002/da.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Herman DS, Huska JA, Keane TM.The PTSD Checklist (PCL): Reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility 9th annual conference of the ISTSS, San Antonio 1993. Paper presented at the [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Huska JA, Keane TM. The PTSD Checklist - Civilian Version (PCL-C) National Center for PTSD; Boston: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss DS, Marmar CR. The Impact of Event Scale- Revised. In: Wilson JP, Keane TM, editors. Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD. Guilford; New York: 1997. pp. 399–411. [Google Scholar]

- Wohlfarth TD, van den Brink W, Winkel FW, ter Smitten M. Screening for posttraumatic stress disorder: An evaluation of two self-report scales among crime victims. Psychological Assessment. 2003;15:101–109. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.15.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohlfarth T, Winkel FW, van den Brink W. Identifying crime victims who are at high risk for post traumatic stress disorder: Developing a practical referral instrument. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2002;105:451–460. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.01099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . Composite International Diagnostic Interview (Core Version 2.1, 12 month version) Author; Geneva Switzerland: 1997. [Google Scholar]