Abstract

In Candida albicans, calcineurin mediates tolerance to azole antifungal drugs, survival in serum, and virulence. In this study, we examined 24 Candida isolates from liver transplant recipients receiving a calcineurin inhibitor as a component of their immunosuppressive therapy. We were unable to detect a difference in susceptibility to calcineurin inhibitors in combination with fluconazole, serum, or calcium in these isolates.

Invasive fungal infections are a significant complication of organ transplantation occurring in up to 42% of liver transplant recipients (5, 8, 23-25). Candida species are the causative agent in 62% to 91% of invasive fungal infections after liver transplantation (23). Manipulation of the gastrointestinal tract during surgery allows translocation of endogenous organisms across the intestinal epithelium, resulting in a unique susceptibility to invasive candidiasis with most infections occurring within the first month posttransplantation.

Although Candida albicans is the predominant species with fluconazole therapy, up to one-third of isolates are non-C. albicans Candida spp., including C. glabrata, C. parapsilosis, and C. tropicalis (11, 16). Although the incidence of fungal disease in liver transplantation has declined largely due to advancements in surgical techniques (27), the high associated mortality (25% to 67%) (14, 23, 25-27) highlights the continued need to understand the pathogenesis of these infections and to develop new treatment strategies.

Two mainstay immunosuppressants in liver transplantation, tacrolimus (FK506) and cyclosporine A (CsA), inhibit the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein phosphatase calcineurin that is required for T-cell activation in response to antigen presentation (6, 7, 9a, 13, 21). CsA and tacrolimus enter the cell and bind to the immunophilins cyclophilin A and FKBP12, respectively, and the resulting drug-protein complexes bind calcineurin (4, 15), preventing T-cell proliferation and suppressing immune responses involved in transplant rejection (2, 3, 6, 9).

In addition to their roles in human immunotherapy, these drugs also inhibit calcineurin function in several human fungal pathogens, including C. albicans, Cryptococcus neoformans, and Aspergillus fumigatus (1, 3, 9, 12, 20, 22, 28). In C. albicans inhibition of calcineurin results in enhanced susceptibility to azole antifungal drugs, susceptibility to cation stresses (including Ca2+, Na+, and Li+), decreased survival in serum, and avirulence in a murine systemic candidiasis model (1, 3, 22). Thus, calcineurin inhibitors could have two potential roles in antifungal therapy, either through use in a combination with azole antifungals or via an intrinsic ability to decrease serum survival.

A previous proof-of-principle study used a rat endocarditis model to show that the combination of fluconazole and cyclosporine A was more effective than either drug alone at treating both primary heart vegetative lesions and kidney lesions formed via hematogenous dissemination (18), suggesting that combination therapy could be effective in an in vivo setting. Although liver transplant patients receive a calcineurin inhibitor, which previous studies suggest could protect against invasive candidiasis (1, 2, 3), a substantial proportion of patients still develop disease. Therefore, we investigated whether Candida isolates from patients immunosuppressed with tacrolimus exhibited altered susceptibility to these drugs with respect to azole tolerance, serum survival, and Ca2+ stress.

Twenty-four Candida isolates were collected from 22 liver transplant recipients receiving tacrolimus. The median duration of immunosuppression prior to isolate collection was 26 days and ranged from 5 days to 11 years. The strains were identified using API carbohydrate assimilation strips (bioMérieux) (16) and CHROMagar Candida (Hardy Diagnostics). Isolates consisted of 18 Candida albicans, 3 Candida glabrata, 2 Candida parapsilosis, and 1 Candida tropicalis (Table 1). The strains were further classified as either invasive or colonizing. Invasive candidiasis was defined as isolation of Candida from at least one blood culture or from normally sterile body fluids either intraoperatively or by percutaneous needle aspiration in patients with signs and symptoms indicative of infection (16). Isolation of Candida from nonsterile samples in patients who did not fulfill the above criteria and for whom antifungal therapy was not employed as treatment was considered to represent colonization. Eleven strains were considered invasive, while 13 were classified as colonizing (17).

TABLE 1.

Candida isolates used in this study

| Isolatea | Sourceb | Speciesc | Antifungal prophylaxis | Fluconazole MICd (μg/ml) | Susceptibilitye

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluconazole + tacrolimus | Serum + tacrolimusf | |||||

| PAT1 ISO1 | Eye | C. albicans | None | 2.0-3.0 | S | S |

| PAT2 ISO1 | Peritoneal fluid | C. albicans | None | 0.25 | S | S |

| PAT3 ISO1 | Peritoneal fluid | C. albicans | None | 0.25-0.38 | S | S |

| PAT4 ISO1 | Peritoneal fluid | C. albicans | None | 0.25-0.38 | S | S |

| PAT5 ISO1 | Blood | C. albicans | None | 0.25-0.38 | S | S |

| PAT6 ISO1 | Hematoma | C. albicans | None | 0.75 | S | S |

| PAT7 ISO1 | BAL | C. albicans | None | 0.38 | S | S |

| PAT8 ISO1 | Sputum | C. albicans | None | 1.5-2.0 | S | S |

| PAT9 ISO1 | BAL | C. albicans | Fluconazole | 0.25 | S | S |

| PAT9 ISO2 | Urine | C. albicans | Fluconazole | 0.5 | S | S |

| PAT9 ISO3 | Sputum | C. albicans | Fluconazole | 0.39-0.50 | S | S |

| PAT10 ISO1 | Urine | C. albicans | None | 0.38-0.50 | S | S |

| PAT11 ISO1 | BAL | C. albicans | Fluconazole | 1.5-2.0 | S | S |

| PAT12 ISO1 | BAL | C. albicans | None | 1.5 | S | S |

| PAT12 ISO2 | Sputum | C. albicans | None | 1.5-2.0 | S | S |

| PAT13 ISO1 | Urine | C. albicans | Voriconazole | 0.25-0.50 | S | S |

| PAT14 ISO1 | Blood | C. albicans | Fluconazole | 0.25-0.38 | S | S |

| PAT15 ISO1 | Pleural fluid | C. albicans | Fluconazole | 0.38-0.50 | S | S |

| PAT16 ISO1 | Peritoneal fluid | C. tropicalis | None | 0.25-0.38 | S | S |

| PAT17 ISO1 | Urine | C. parapsilosis | None | 1.5-2.0 | S | S |

| PAT18 ISO1 | BAL | C. glabrata | Voriconazole | >256 | S | R |

| PAT19 ISO1 | Urine | C. glabrata | Voriconazole | >256 | S | R |

| PAT20 ISO1 | Blood | C. parapsilosis | Fluconazole | 0.75-1.5 | S | S |

| PAT21 ISO1 | Blood | C. glabrata | Fluconazole | 32-48 | S | S |

Strains in bold are invasive isolates.

BAL, broncheal alveolar lavage; eye, endophthalmitis.

Species was determined by API testing.

Fluconazole MICs were determined by E-Test; resistance, MIC ≥ 64 μg/ml; sensitive-dose dependent, MIC = 16 to 32 μg/ml; sensitive, MIC ≤ 8 μg/ml.

S, susceptible; R, resistant.

Susceptibility as measured in liquid culture. S, sensitive (population change < onefold); R, resistant (population change > onefold).

In vitro fluconazole MIC testing was performed in triplicate for all isolates using E-test strips (AB Biodisk) on RPMI medium and confirmed by NCCLS microdilution testing (19). Only two isolates, both Candida glabrata, were resistant to fluconazole (MIC > 64 μg/ml). All other isolates were susceptible to fluconazole, except C. glabrata isolate PAT21 ISO1, which was sensitive-dose dependent (Table 1). All three C. glabrata isolates with decreased susceptibility to fluconazole were collected from patients who had received an azole as antifungal prophylaxis (Table 1); however, azole prophylaxis was not always associated with fluconazole resistance.

Previous studies with Candida have shown that treatment with a calcineurin inhibitor results in enhanced susceptibility to azole antifungals (1, 3, 9a, 22). Eleven of the strains were from patients who had received prophylactic treatment with an azole concurrently with their tacrolimus immunosuppressive therapy. The average duration of azole therapy was 86 days and ranged from 3 to 397 days.

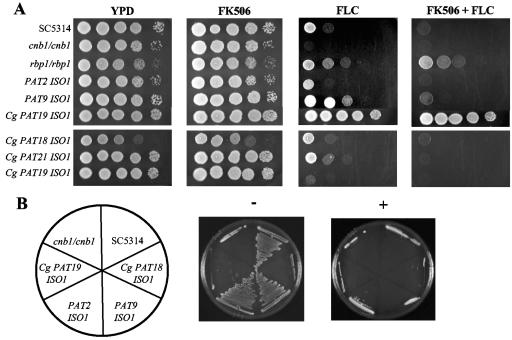

We tested whether the clinical isolates were susceptible to the combination of fluconazole and tacrolimus (Fig. 1) or CsA (data not shown) by serial spot dilution assays. All strains were counted with a hemacytometer, normalized to an initial concentration of 107 cells/ml, and 1:10 serial dilutions were spotted onto YPD or YPD containing 10 μg/ml fluconazole (Diflucan; Pfizer) with or without 1 μg of tacrolimus (Prograf; Astellas Pharma US, Inc.) per ml. All plates were incubated at 30°C for 24 to 48 h and observed for growth. Controls included C. albicans strains SC5314 (wild-type strain), a homozygous calcineurin B deletion mutant (JRB64, cnb1/cnb1), and an rbp1/rbp1 deletion mutant (YAG171) that lacks FKBP12 and is therefore unresponsive to tacrolimus. Due to their resistance to fluconazole alone, the C. glabrata isolates were also tested on solid medium containing 256 μg per ml fluconazole with and without 1 μg per ml tacrolimus. At the higher concentration of fluconazole all three C. glabrata isolates demonstrated susceptibility to the combination of fluconazole and tacrolimus. Therefore, despite previous exposure to tacrolimus, there was no selection for resistance to the combination of calcineurin inhibitors and fluconazole in any of the isolates.

FIG. 1.

Invasive and noninvasive clinical isolates. (A) Isolates were grown for 48 h at 30°C on YPD medium alone or containing tacrolimus (1 μg per ml), fluconazole (FLC; 10 μg per ml, upper panels; 256 μg per ml, lower panels), or both drugs. Control strains SC5314 (wild type), cnb1/cnb1 (calcineurin deletion mutant), and rbp1/rbp1 (FKBP12 deletion mutant) were tested along with representative clinical isolates. (B) Isolates were streaked on 50% FBS medium alone (−) or containing 1 μg per ml tacrolimus (+) and grown for 48 h at 30°C. C. glabrata isolates show reduced growth compared with C. albicans strains on solid serum-containing medium. All strains failed to grow in the presence of tacrolimus and serum.

Calcineurin is also required for Candida albicans survival in serum (3, 22). Wild-type C. albicans strains grow robustly in fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 30°C, but lose viability under the same conditions when CsA or tacrolimus is added. Therefore it is possible that calcineurin inhibitors alone would exert an intrinsic antifungal activity in vivo when present in serum, which would hinder hematogenous dissemination.

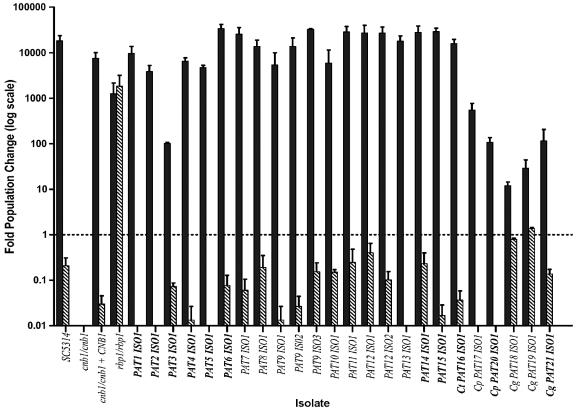

We hypothesized that successfully invading isolates may have a decreased susceptibility to the combination of calcineurin inhibitors and serum. We measured the fold population change of all isolates after 24 h growth in FBS (Gibco certified FBS) with or without 1 μg per ml tacrolimus (Fig. 2). Cells were grown overnight in YPD at 30°C, washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline, inoculated into FBS at a concentration of approximately 2,000 cells per ml, and incubated for 24 h at 30°C. Dilutions were plated onto YPD plates for CFU counts at 0 and 24 h. The population change was determined by dividing the CFU at 24 h by the CFU at 0 h. Strains were also streaked onto serum plates (50% FBS, distilled H2O, and 2% Bacto agar) with or without 1 μg per ml tacrolimus (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 2.

Clinical Candida isolates are not resistant to the combination of serum and tacrolimus. The population change after 24 h growth in liquid FBS in the presence (diagonal hatched bars) or absence (solid bars) of 1 μg per ml of tacrolimus is shown. Invasive isolates are in bold. Error bars represent the standard error calculated from three independent experiments. Ct, Candida tropicalis; Cp, Candida parapsilosis; Cg, Candida glabrata.

All C. albicans strains were able to grow robustly in liquid serum culture, undergoing a 10,000- to 100,000-fold increase in population. By contrast, the C. glabrata and C. parapsilosis strains underwent more limited expansion in liquid serum, on the order of 10- to 100-fold (P = 0.0005 and P = 0.0045, respectively) (Fig. 2). In accordance, the C. glabrata isolates did not exhibit visible growth on solid serum medium as judged by the failure to form colonies (Fig. 1B). All isolates demonstrated reduced growth in serum containing tacrolimus. Only two isolates, C. glabrata PAT18 ISO1 and PAT19 ISO1, were resistant to the combination. Although these strains have a reduced growth rate in the presence of tacrolimus, the population change was still greater than or approximately onefold, indicating continued growth or stasis rather than a reduction in viability (population change < 1-fold) as seen with all other isolates. Interestingly, invasive and colonizing isolates did not differ in their ability to proliferate in serum, and invasive isolates did not show selection for resistance to the combination of serum and calcineurin inhibitor.

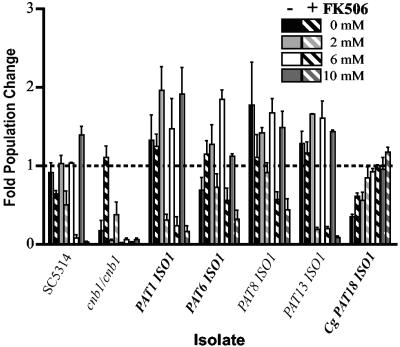

Recent studies have indicated that calcium is the component within serum that is toxic to C. albicans calcineurin mutants (2). Fetal bovine serum contains approximately 3.5 to 4.0 mM calcium, a concentration at which calcineurin mutants are unable to survive (2). Although there was no difference in susceptibility to serum and tacrolimus between the invasive and colonizing isolates, we determined whether any exhibited altered calcium susceptibility (Fig. 3). The clinical isolates were prepared as in the serum assay and inoculated into phosphate-buffered saline with or without 1 μg per ml tacrolimus and 0, 2, 6, or 10 mM CaCl2 (Sigma). Cultures were incubated at 30°C and CFU were counted at 0 and 24 h.

FIG. 3.

Calcium susceptibility profile of representative invasive and colonizing isolates. Population change was determined after 24 h incubation in phosphate-buffered saline containing 0, 2, 6, or 10 mM CaCl2 alone (solid bars) or with 1 μg per ml tacrolimus (FK506) (diagonally striped bars). All C. albicans isolates had significantly decreased viability in the presence of tacrolimus at 6 mM and 10 mM (P < 0.05, two-tailed t test). PAT1 ISO1 and PAT13 ISO1 also showed significant reduction in viability at 2 mM (P < 0.05). Invasive isolates are in bold. Error bars represent the standard error calculated from three independent experiments. Cg, Candida glabrata.

For each concentration of calcium tested we compared the population change of the tacrolimus-treated and untreated samples. Overall, there was no difference in the calcium susceptibility patterns of invasive and colonizing isolates. In the presence of tacrolimus all of the C. albicans isolates had significant reductions in viability at the 6 mM and 10 mM calcium concentrations (P < 0.05, two-tailed, t test). Additionally, at 2 mM calcium 7 out of the 18 C. albicans strains had significantly reduced viability (P < 0.05), and the remaining strains showed a modest decrease that was not statistically significant. The C. glabrata isolates demonstrated an increase in viability as the concentration of calcium in the medium increased (population change in 0 mM or 2 mM calcium versus 10 mM calcium, P < 0.05). This is similar to the situation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, where inhibition of calcineurin results in decreased survival in low-calcium environments (10).

The purpose of this study was to determine if tacrolimus used for immunosuppression could exert enough antifungal activity in vivo in combination with fluconazole or serum to select resistant isolates. Analysis of isolates from liver transplant recipients did not reveal any differences in responsiveness to tacrolimus combined with serum, fluconazole, or calcium.

Previous studies have shown that in combination with fluconazole, tacrolimus has a MIC of ≤40 ng/ml (9). Tacrolimus therapeutic blood levels clinically can range from 5 to 20 ng/ml (trough level) to 68.5 ± 30 ng/ml (peak level). Although the levels obtained in the blood could be high enough to exert an effect, the local tissue concentrations that cells are exposed to in vivo is not known. One hypothesis for why resistance to calcineurin inhibitors may not develop in invasive isolates is that the local concentration of drug to which fungal cells are exposed is less than that needed to exert antifungal action. This could be a result of a lower therapeutic dose than optimal for antifungal activity with serum or fluconazole or sequestration of drug through binding to plasma proteins, or Candida may be sheltered from drug exposure by residing within tissues or within cells where drug concentrations may be lower.

The use of current clinical formulations of calcineurin inhibitors to augment antifungal therapy is hindered by their immunosuppressive effects, effects which likely outweigh the antifungal properties. Thus, nonimmunosuppressive analogs that retain the ability to target fungal calcineurin could have greater potential as therapeutic drugs. Alternatively, the combination of calcineurin inhibitors with other agents that augment their intrinsic antifungal activity may be a viable therapeutic approach.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Chiatogu Onyewu and Jill Blankenship for discussions and helpful suggestions.

These studies were supported by RO1 grants AI50438 (J.H.), AI42159 (J.H.), and AI054719 (N.S.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bader, T., B. Bodendorfer, K. Schröppel, and J. Morschhäuser. 2003. Calcineurin is essential for virulence in Candida albicans. Infect. Immun. 71:5344-5354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blankenship, J. R., and J. Heitman. 2005. Calcineurin is required for Candida albicans to survive calcium stress in serum. Infect. Immun. 73:5767-5774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blankenship, J. R., F. L. Wormley, M. K. Boyce, W. A. Schell, S. G. Filler, J. R. Perfect, and J. Heitman. 2003. Calcineurin is essential for Candida albicans survival in serum and virulence. Eukaryot. Cell 2:422-430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cardenas, M. E., R. S. Muir, T. Breuder, and J. Heitman. 1995. Targets of immunophilin-immunosuppressant complexes are distinct highly conserved regions of calcineurin A. EMBO J. 14:2772-2783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castaldo, P., R. J. Stratta, R. P. Wood, R. S. Markin, K. D. Patil, M. S. Shaefer, A. N. Langnas, and B. W. Shaw, Jr. 1991. Fungal infections in liver allograft recipients. Transplant Proc. 23:1967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clipstone, N. A., and G. R. Crabtree. 1993. Calcineurin is a key signaling enzyme in T lymphocyte activation and the target of the immunosuppressive drugs cyclosporin A and FK506. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 696:20-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clipstone, N. A., and G. R. Crabtree. 1992. Identification of calcineurin as a key signalling enzyme in T-lymphocyte activation. Nature 357:695-697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collins, L. A., M. H. Samore, M. S. Roberts, R. Luzzati, R. L. Jenkins, W. D. Lewis, and A. W. Karchmer. 1994. Risk factors for invasive fungal infections complicating orthotopic liver transplantation. J. Infect. Dis. 170:644-652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cruz, M. C., D. S. Fox, and J. Heitman. 2001. Calcineurin is required for hyphal elongation during mating and haploid fruiting in Cryptococcus neoformans. EMBO J. 20:1020-1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9a.Cruz, M. C., A. L. Goldstein, J. R. Blankenship, M. Del Poeta, D. Davis, M. E. Cardenas, J. R. Perfect, J. H. McCusker, and J. Heitman. 2002. Calcineurin is essential for survival during membrane stress in Candida albicans. EMBO J. 21:546-559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cunningham, K. W., and G. R. Fink. 1994. Calcineurin-dependent growth control in Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutants lacking PMC1, a homolog of plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPases. J. Cell Biol. 124:351-363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fortún, J., A. López-San Roman, J. J. Velasco, A. Sánchez-Sousa, E. de Vicente, J. Nuño, C. Quereda, R. Bárcena, G. Monge, A. Candela, A. Honrubia, and A. Guerrero. 1997. Selection of Candida glabrata strains with reduced susceptibility to azoles in four liver transplant patients with invasive candidiasis. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 16:314-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fox, D. S., M. C. Cruz, R. A. Sia, H. Ke, G. M. Cox, M. E. Cardenas, and J. Heitman. 2001. Calcineurin regulatory subunit is essential for virulence and mediates interactions with FKBP12-FK506 in Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol. Microbiol. 39:835-849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fruman, D. A., C. B. Klee, B. E. Bierer, and S. J. Burakoff. 1992. Calcineurin phosphatase activity in T lymphocytes is inhibited by FK506 and cyclosporin A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:3686-3690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gayowski, T., I. R. Marino, N. Singh, H. Doyle, M. Wagener, J. J. Fung, and T. E. Starzl. 1998. Orthotopic liver transplantation in high-risk patients: risk factors associated with mortality and infectious morbidity. Transplantation 65:499-504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hemenway, C. S., and J. Heitman. 1999. Calcineurin. Structure, function, and inhibition. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 30:115-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Husain, S., J. Tollemar, E. A. Dominguez, K. Baumgarten, A. Humar, D. L. Paterson, M. M. Wagener, S. Kusne, and N. Singh. 2003. Changes in the spectrum and risk factors for invasive candidiasis in liver transplant recipients: prospective, multicenter, case-controlled study. Transplantation 75:2023-2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Land, G. A., B. A. Harrison, K. L. Hulme, B. H. Cooper, and J. C. Byrd. 1979. Evaluation of the new API 20C strip for yeast identification against a conventional method. J. Clin. Microbiol. 10:357-364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marchetti, O., J. M. Entenza, D. Sanglard, J. Bille, M. P. Glauser, and P. Moreillon. 2000. Fluconazole plus cyclosporine: a fungicidal combination effective against experimental endocarditis due to Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2932-2938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 1997. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts. Approved standard M27-A. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 20.Odom, A., S. Muir, E. Lim, D. L. Toffaletti, J. Perfect, and J. Heitman. 1997. Calcineurin is required for virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans. EMBO J. 16:2576-2589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Keefe, S. J., J. Tamura, R. L. Kincaid, M. J. Tocci, and E. A. O'Neill. 1992. FK-506- and CsA-sensitive activation of the interleukin-2 promoter by calcineurin. Nature 357:692-694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanglard, D., F. Ischer, O. Marchetti, J. Entenza, and J. Bille. 2003. Calcineurin A of Candida albicans: involvement in antifungal tolerance, cell morphogenesis and virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 48:959-976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh, N. 2003. Fungal infections in the recipients of solid organ transplantation. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 17:113-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singh, N. 1997. Infections in solid-organ transplant recipients. Am. J. Infect. Control 25:409-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh, N. 1998. Infectious diseases in the liver transplant recipient. Semin. Gastrointest. Dis. 9:136-146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh, N., T. Gayowski, M. M. Wagener, H. Doyle, and I. R. Marino. 1997. Invasive fungal infections in liver transplant recipients receiving tacrolimus as the primary immunosuppressive agent. Clin. Infect. Dis. 24:179-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singh, N., M. M. Wagener, I. R. Marino, and T. Gayowski. 2002. Trends in invasive fungal infections in liver transplant recipients: correlation with evolution in transplantation practices. Transplantation 73:63-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steinbach, W. J., W. A. Schell, J. R. Blankenship, C. Onyewu, J. Heitman, and J. R. Perfect. 2004. In vitro interactions between antifungals and immunosuppressants against Aspergillus fumigatus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:1664-1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]