Abstract

In looking for outcome differences beyond rates of cure, we prospectively compared the symptom resolution, side effects, and processes of care between the use of clarithromycin and gatifloxacin for the treatment of radiographically confirmed community-acquired pneumonia. We conducted a multicenter, randomized, open-label study comparing gatifloxacin monotherapy to clarithromycin alone or combined with ceftriaxone for patients with multiple risk factors. We measured the return to usual activities and symptoms over seven interviews ending 42 days after randomization. Admission and hospital discharge decision support were provided to treating physicians. We enrolled 266 patients over the age of 18 years between September 2000 and June 2003. The groups were similar in age and gender, with a mean age of 53.5 ± 19.4 years, and were 54% female. Patient severity as determined by the number of risk factors and the Pneumonia Severity Index was similar between groups; 95% of the patients were low risk. A total of 91% of patients completed at least five of seven symptom interviews. In the clarithromycin study arm, 64% received concomitant therapy with ceftriaxone. We found no significant difference in return to usual activities, pneumonia-specific symptom scores, and 12-item short-form health survey scores. Individual symptom scores were similar except for bad taste and injection site soreness, which were higher in clarithromycin patients. The rates of hospital admission and length of stay were similar. The cost of antibiotic was higher in the clarithromycin group: $257 versus $110 for gatifloxacin. We found that gatifloxacin monotherapy is similar to clarithromycin given with or without ceftriaxone for the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia, except that antibiotic cost, bad taste, and injection site soreness favor the use of gatifloxacin.

Community-acquired pneumonia accounts for 4.5 million physician visits in the United States yearly and $8 to $12 billion in direct costs (1, 14). Pneumonia also has indirect costs related to work absences or diminished productivity from pneumonia-related symptoms.

Comparisons between antibiotics for treatment of community-acquired pneumonia usually demonstrate equivalence when the endpoint is clinical cure beyond 14 days after randomization. Differences between antibiotics in bioavailability, in vitro activity against respiratory pathogens, peak concentration, half-life, cost, and side effects might affect not only clinical cure rates but also how rapidly patients regain home independence and return to work. The latter issues of antibiotic-related recovery are not often addressed in clinical trials. North American guidelines primarily recommend the use of macrolides and quinolones for the treatment of outpatient pneumonia, of which gatifloxacin and clarithromycin are representative compounds (6, 11, 12, 13). Gatifloxacin's MIC against 90% of isolates (MIC90) is lower than that of clarithromycin against Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae. Oral gatifloxacin is 96% bioavailable versus 40% for clarithromycin (5). Gatifloxacin's half-life of 7 to 9 h allows once-daily dosing, whereas clarithromycin has a half-life of 5 to 7 h and is dosed twice daily. The time to peak serum concentration is 1 h for gatifloxacin versus 2 h for clarithromycin. Clarithromycin is metabolized to 14-OH clarithromycin that has clinically significant antimicrobial activity. Gatifloxacin is a DNA gyrase inhibitor, while clarithromycin inhibits protein synthesis by binding to the 50A ribosomal subunit. Side effects and drug interactions also differ. We hypothesized that these differences would result in different timing of the symptom resolution in patients with community-acquired pneumonia. We also hypothesized that the likelihood of hospitalization and the length of hospital stay would differ, since gatifloxacin's oral bioequivalence would make intravenous administration necessary only in patients unable to take oral medications.

(This work was presented in part on 26 October 2004 at CHEST, Seattle, Wash.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We conducted a randomized, multicenter, prospective study comparing gatifloxacin monotherapy with oral clarithromycin given alone or combined with ceftriaxone. We chose an open-label design to study whether different antibiotics change physician decision-making regarding need for hospitalization or timing of the hospital discharge. All study sites were located in Utah and comprised three groups: (i) four urban urgent care centers and two urban pulmonary outpatient office practices in Salt Lake City; (ii) three outpatient clinics and the hospital emergency department in rural Sanpete Valley; and (iii) the LDS Hospital Emergency Department (ED) in Salt Lake City.

Block randomization ensured that equal numbers were randomized into each study arm from study site groups. Randomly generated sequential envelopes were kept at a remote site to prevent study physicians from knowing treatment allocation prior to randomization.

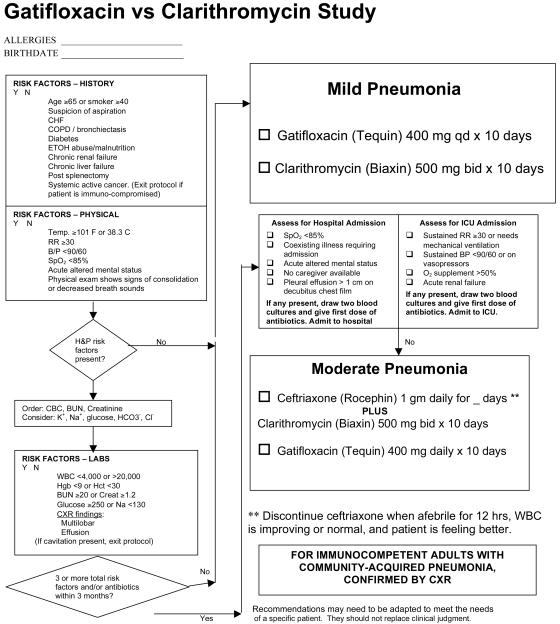

The usual treating physician identified patients and obtained consent after reviewing eligibility and exclusion criteria with an on-call study nurse. The treating physician completed our pneumonia guideline outpatient form (3), adapted for the purposes of the present study (Fig. 1). Clinical care except for antibiotic selection was at the discretion of treating physicians; Fig. 1 provided admission decision support and logic for addition of ceftriaxone but was a guideline only. The LDS Hospital Institutional Review Board approved the present study.

FIG. 1.

Decision support logic for the administration of ceftriaxone and hospital admission.

Inclusions and exclusions.

The inclusion criteria were age ≥18 years, a chest radiograph demonstrating a parenchymal infiltrate not attributable to another cause, a diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia by the treating physician, and onset within 2 weeks of cough, fever, fatigue, chest pain, or dyspnea. Both the enrolling physician and a radiologist confirmed the presence of pneumonia on a chest radiograph. The exclusion criteria were: (i) immunocompromised patients (systemic active cancer, chronic prednisone therapy of >10 mg per day, use of chemotherapy medications, infection with human immunodeficiency virus); (ii) pregnancy or nursing; (iii) antibiotic use of >24 h within 7 days; (iv) bronchiectasis; (v) cavitary disease; (vi) moderate to severe liver disease; (vii) meningitis; (viii) allergy to the study antibiotic; (ix) the patient desired admission at a nonstudy hospital; (x) hospitalization within prior 14 days; (xi) severe pneumonia as defined by the presence of a respiratory rate of >30 per min, a blood pressure of <90/60 mm Hg, new renal failure, or an oxygen requirement of >50%; (xii) inability to communicate in English and/or be available for the 6-week study period; and (xiii) no telephone access.

Treatment arms.

The treatment arms were as follows. (i) Oral gatifloxacin was administered at 400 mg once daily for 10 days and given intravenously if the subject was unable to tolerate oral therapy. Patients with a creatinine level of >2.0 received 200 mg once a day. (ii) Oral clarithromycin was administered at 500 mg twice daily for 10 days. Inpatients, or outpatients with ≥3 risk factors (Fig. 1), were directed to also receive ceftriaxone 1 gm intravenously or intramuscularly daily until all of the following criteria were met: temperature of <38°C for 16 h, decreasing white blood count, and pneumonia symptom improvement. The same criteria guided the intravenous to oral gatifloxacin switch and hospital discharge. Ceftriaxone could be added to clarithromycin in patients with <3 risk factors if it was deemed necessary by the treating physician. Physicians initiated antibiotic therapy immediately after randomization. Intramuscular ceftriaxone was administered routinely with lidocaine to minimize injection site soreness.

Outcome measures.

We measured the time to return to usual activities, determined the pneumonia-specific symptom scores (10), and completed the 12-item short-form health survey (SF-12) in person for hospitalized patients or by phone interviews for outpatients within 24 h of randomization. We also interviewed subjects on days 2, 5, 9, 14, 28, and 42. The primary endpoint was the “time to return to normal activities”—defined as the number of days from study enrollment to the interview date when the patient could engage in normal activities. We calculated the SF-12 physical and mental scales using the 1998 general U.S. population transformation constant (16). We calculated the Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) (7) and summed the risk factors (Fig. 1). The individual symptoms queried are shown in Table 2. More specifically, taste perversion was asked by the question: “bad taste in mouth, yes or no?” If yes, how severe was it: a little, moderately, quite a bit, or extremely? The question regarding injection site soreness was asked as follows: if you had an injection of pneumonia medication, have you had pain at the place the medication was given? The severity was graded as for bad taste. Antibiotic costs were calculated by averaging 2003 retail prices at three Utah pharmacies of 10 days of gatifloxacin, clarithromycin, and 1 to 7 days of ceftriaxone not including supplies and professional component. Other costs of pneumonia care were not included.

TABLE 2.

Percentage of patients with specific symptoms grouped by time from diagnosis

| Symptom | Txa | % of patients at (time from diagnosis):

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Day 2 | Day 5 | Day 9 | Wk 2 | Wk 4 | Wk 6 | ||

| Fatigue | C/C | 97 | 94 | 86 | 75 | 62 | 49 | 30 |

| Gati | 93 | 92 | 84 | 66 | 51 | 45 | 34 | |

| Chest pain | C/C | 58 | 48 | 38 | 21 | 21 | 10 | 5 |

| Gati | 48 | 41 | 26 | 21 | 13 | 13 | 11 | |

| Nausea | C/C | 37 | 25 | 13 | 10 | 5 | 2 | 0 |

| Gati | 39 | 31 | 20 | 9 | 7 | 3 | 4 | |

| Vomiting | C/C | 16 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Gati | 13 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | |

| Diarrhea | C/C | 20 | 21 | 23 | 12 | 6 | 1 | 5 |

| Gati | 17 | 16 | 21 | 15 | 9 | 8 | 3 | |

| Light-headed | C/C | 67 | 43 | 34 | 29 | 16 | 8 | 4 |

| Gati | 60 | 56 | 39 | 19 | 13 | 13 | 12 | |

| Dizzy | C/C | 48 | 27 | 21 | 16 | 10 | 10 | 4 |

| Gati | 48 | 44 | 23 | 14 | 12 | 9 | 6 | |

| Difficulty breathing | C/C | 78 | 73 | 65 | 49 | 36 | 23 | 13 |

| Gati | 76 | 61 | 52 | 39 | 25 | 20 | 13 | |

| Cough without phlegm | C/C | 60 | 55 | 59 | 64 | 53 | 34 | 14 |

| Gati | 71 | 71 | 69 | 59 | 55 | 33 | 22 | |

| Cough with phlegm | C/C | 74 | 82 | 81 | 58 | 48 | 38 | 16 |

| Gati | 78 | 82 | 81 | 60 | 41 | 27 | 23 | |

| Decreased appetite | C/C | 83 | 61 | 51 | 28 | 23 | 12 | 5 |

| Gati | 76 | 71 | 51 | 28 | 20 | 14 | 12 | |

| Fever | C/C | 70 | 29 | 9 | 8 | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Gati | 71 | 34 | 17 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 3 | |

| Wheezing | C/C | 64 | 58 | 42 | 32 | 24 | 14 | 7 |

| Gati | 63 | 52 | 44 | 31 | 20 | 16 | 14 | |

| Bad taste | C/C | 51 | 56 | 56 | 49 | 18 | 4 | 2 |

| Gati | 50 | 47 | 39 | 28 | 14 | 10 | 6 | |

| Rash | C/C | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Gati | 5 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

Tx, treatment; Gati, gatifloxacin; C/C, clarithromycin with or without ceftriaxone.

Statistics.

The time to return to normal activities was compared by Kaplan-Meier plot and modeled by using parametric survival methods for interval censored data (9). Regression diagnostics indicated that a lognormal survival model with interval censoring and Gaussian frailties provided a reasonable fit. Other parametric models including loglogistic or Weibull survival and gamma and t frailties produced similar results. Median times until return to work in the gatifloxacin and clarithromycin groups, their ratio, and 95% confidence intervals were calculated.

Chi-square statistics were computed to test for differences in the distributions of risk class and subsequent risk category between treatment arms. The number of risk factors and PSI between treatment arms were compared by using unpaired, two-tailed t tests. Individual symptom scores were transformed into a composite score by dichotomizing them into present or absent, multiplying the 15 individual components by 6.67, and summing them to produce a range of 0 to 100.

Because the distribution of lengths of hospital stay was skewed, the median lengths of stay for patients were compared. The median test for location uses a bootstrap method (4) to estimate the standard error. Other statistical analyses for patient demographics and endpoint data were conducted by using unpaired t tests (to compare location of means), or Fisher exact tests or chi-square tests (to compare distributions).

All computerized statistical tests were performed by using CPM Desktop (release 5.3.4.98; Electroglas, Corvallis, OR). The level of statistical significance for all tests was <0.05.

RESULTS

Patients.

A total of 266 patients were initially enrolled between September 2000 and June 2003, but 5 dropped out before receiving the study drug, leaving 261 patients for the intent to treat analysis. Fifteen additional patients did not complete antibiotic therapy. The likelihood of dropping out did not differ between study sites or by antibiotic therapy group. Common reasons for dropping out included the discovery of exclusion criteria not identified before randomization, the withdrawal of consent, and communication problems identified after randomization. A total of 33 (12.4%) patients were enrolled from the LDS Hospital ED, 95 (35.7%) were enrolled from the Sanpete Valley facility, and 138 (51.9%) were enrolled from the urgent care centers. A total of 91% of the patients completed at least five of seven symptom interviews, with 88% completing the last interview at 42 days.

The patient severity level as determined by the number of risk factors and the PSI was similar between groups, with most patients being at low risk for adverse outcomes (PSI classes 1 to 3 comprised 95% of each group; P = 0.78). The average number of risk factors was 1.5 for both groups (P = 0.23). The mean age in the clarithromycin group was 53.2 ± 19.1 years versus 53.9 ± 19.8 for gatifloxacin (P = 0.81). Females comprised 53.7% of the clarithromycin group versus 53.2% for gatifloxacin (P = 0.87). Thirty-six patients (13.8%) were admitted to the hospital, all but one within 4 h of study randomization.

Patients from the urgent care centers were younger than those from Sanpete Valley (47.7 ± 16.7 versus 61.2 ± 19.4 years; P < 0.001). The mean age of patients from the LDS ED was not statistically different from either group at 56.4 ± 21.9 years. Patients enrolled at the LDS ED and Sanpete Valley had higher PSI scores and more risk factors than did the urgent care center patients.

Concomitant ceftriaxone.

A total of 64% of the clarithromycin patients received dual therapy with ceftriaxone: 44% urgent care patients, 78% LDS ED patients, and 88% Sanpete Valley patients (P < 0.001 for comparison of LDS ED and Sanpete Valley patients with urgent care center patients). The average number of ceftriaxone doses was 2 (range, 1 to 7; mode 1). Gender did not change the likelihood of receiving ceftriaxone. Patients receiving ceftriaxone averaged two risk factors, whereas patients treated with clarithromycin alone averaged one risk factor (P = 0.004).

Fifteen patients had cultures performed: 11 blood and 7 expectorated sputum cultures. Each study group had one blood culture and one sputum culture positive for S. pneumoniae. The four isolates (separate patients) were sensitive to erythromycin, levofloxacin, and ceftriaxone; isolates were not tested specifically for susceptibility to clarithromycin or gatifloxacin. To provide additional local susceptibility data during the last 2 study years, we tested 100 S. pneumoniae isolates from blood, pleural space, or lower respiratory tract sources in symptomatic adults from the Salt Lake Valley. The sensitivity to erythromycin (comparable to clarithromycin, which was not tested) was 75% versus 98% for gatifloxacin. The MIC90 for gatifloxacin was 0.37.

The initial chest radiograph demonstrated two pleural effusions in the gatifloxacin group and three in the clarithromycin group. No study patient demonstrated the spread of infection to nonpulmonary sites.

Clinical outcomes.

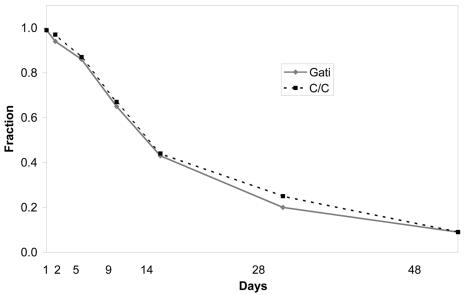

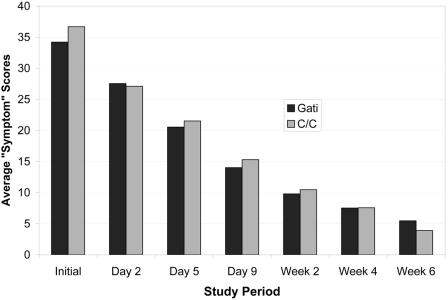

The interval-censored lognormal model estimated the median time until return to usual activity to be 15 days in the gatifloxacin group and 16.1 days among patients receiving clarithromycin (P = 0.58). The ratio of median times to return to work was 0.93 with a 95% confidence interval of 0.73 to 1.19. These data are presented graphically by a Kaplan-Meier plot (Fig. 2). We found no significant difference between study drugs in composite symptom scores (Fig. 3). Average SF-12 physical and mental scale scores at baseline and at the last interview did not differ significantly between groups (Table 1). Cox regression revealed no differences between treatment arms, study sites, or combinations of treatment and site.

FIG. 2.

Fraction of patients who had not returned to usual activities at each point of contact.

FIG.3.

Average symptom scores for patients randomized to gatifloxacin or clarithromycin are compared.

TABLE 1.

SF-12 scores by group at first and last visits

| SF-12 scale | Mean SF-12 score ± SD at:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| First visit | Last visit | |

| Physical scale | ||

| Clarithromycin | 30.0 ± 6.9 | 49.8 ± 6.7 |

| Gatifloxacin | 30.6 ± 8.0 | 49.0 ± 6.6 |

| Mental scale | ||

| Clarithromycin | 52.3 ± 6.2 | 49.2 ± 4.2 |

| Gatifloxacin | 51.9 ± 5.6 | 49.2 ± 4.2 |

Of individual symptoms examined, only bad taste and injection site soreness differed (Table 2). Bad taste was noted by 49% of patients treated with clarithromycin versus 28% for gatifloxacin at 9 days postrandomization (P = 0.007). Of the clarithromycin patients noting “bad taste” at 9 days, 2% noted “extreme,” 6% noted “quite a bit,” 12% noted “moderate,” and 29% noted “a little.” Of patients randomized to gatifloxacin at 9 days, 2% noted “extreme” bad taste, 3% noted “quite a bit,” 7% noted “moderate,” and 16% noted “a little.” At day 2, 33% of the clarithromycin patients noted moderate to extreme bad taste versus 27% of the gatifloxacin patients (not statistically different).

The difference in injection site soreness between gatifloxacin and clarithromycin/ceftriaxone patients was statistically significant (P < 0.001).

Injection site soreness was noted by 45% of the patients who received intramuscular ceftriaxone on day 1: 21% reported “a little,” 11% reported “moderate,” 11% reported “quite a bit,” and 3% reported “extreme.” A total of 30% had pain on day 2, but only 3% had pain by day 5. Patients who received intravenous injections of ceftriaxone and gatifloxacin mostly rated their pain as “a little,” with no significant difference between the groups.

Drug-related discontinuation was similar. Two patients were discontinued from gatifloxacin because of rash, and three were judged treatment failures by their treating physician and switched to nonstudy antibiotics. Two patients were discontinued from clarithromycin because of rash, two were discontinued because of nausea and vomiting, and two were judged treatment failures and switched to nonstudy antibiotics.

The rate of hospital admission was not different between groups, with 23 of 136 (16.9%) for ceftriaxone/clarithromycin versus 13 of 125 (10.4%) for gatifloxacin (P = 0.15). Patients were more likely to be admitted from the ED (19 of 31 [61%]) or Sanpete Valley sites (15 of 94 [16%]) than from the urgent care centers (2 of 136 [2%]) (P < 0.001 for all comparisons). The admission rate did not differ by gender.

Length of stay was not different between the groups, with a median of 2 days and a mean of 5.3 days for ceftriaxone/clarithromycin patients versus a median of 4 days and a mean of 7.1 days for gatifloxacin patients (P = 0.26 by test of medians). The length of stay was similar between the LDS and Sanpete Valley hospitals (each a median of 3 days) and similar by gender or site of initial presentation.

When we combine the admission and length of stay data, the mean numbers of hospital days per patient were similar: 0.81 days for gatifloxacin patients versus 0.89 days for clarithromycin patients.

One death occurred in a patient who progressively worsened a few hours after randomization to gatifloxacin. She was transferred to intensive care and received additional antibiotics prior to death from multiple organ failure.

The cost of therapy in the clarithromycin arm varied by the number of days of concomitant ceftriaxone. Patients averaged two doses of ceftriaxone, and the antibiotic cost per patient was higher in the clarithromycin group: $257 versus $110 for gatifloxacin.

DISCUSSION

This study attempted to mimic real world outpatient treatment of community-acquired pneumonia, where nonpneumonia specialists select antibiotics and determine the need for hospitalization (2). Mortality is low among outpatients, and few fail antibiotic therapy. We hypothesized that differences between the study antibiotics in bioavailability, half-life, mechanism of action, and in vitro activity against respiratory pathogens would result in different timing of the symptom resolution and differences in the process of care and side effects. However, we could not demonstrate a difference in time to return to usual activity. Confidence intervals are provided in lieu of a post hoc power calculation (8). Differences between the two regimens in bad taste and injection site soreness favored gatifloxacin, as did the direct cost of antibiotic therapy.

Most patients at higher risk of adverse outcome received parenteral ceftriaxone in addition to clarithromycin, possibly obscuring hypothesized outcome differences between the oral drugs. The Intermountain Health Care Pneumonia Guideline had been used by most study physicians prior to the beginning of the present study and features combination therapy with azithromycin plus ceftriaxone for outpatients and inpatients with moderate to severe disease. Figure 1 was derived from this guideline, differing only in the antibiotics listed. Prior guideline experience may have made physicians reluctant to prescribe clarithromycin monotherapy, even for patients with fewer than three risk factors (3, 15). Following the study guideline would have directed fewer doses of ceftriaxone and narrowed the cost difference between regimens, assuming equivalent clinical outcomes.

Limitations of the present study include not recording the number of patients screened but not enrolled. The study design of subject identification and randomization by treating physicians made this infeasible. In addition, only 5% of the enrolled patients belonged to the PSI risk classes where clinical outcomes are less favorable. This is partly attributable to the pneumonia patient population seen at urgent care centers. We previously reported that urgent care patients are young and have few risk factors, with consequent low admission rate and rare treatment failures (15). Also, treatment study arms were less tightly controlled than common in randomized, double-blind studies. We chose this study design to determine whether differences in bioavailability and dosage frequency between study antibiotics would be utilized by physicians in determining the need for hospitalization and the length of the hospital stay. Finally, the hospital admission rate was lower than expected, limiting the power of the study to detect a significant difference in rate of admission and the length of stay.

Conclusion.

Gatifloxacin monotherapy is similar to clarithromycin (combined with ceftriaxone for patients with multiple risk factors) in time to return to usual activities. Taste, antibiotic cost, and injection site soreness favored the use of gatifloxacin, although ceftriaxone use was responsible for the latter two differences. The liberal use of combination therapy in the clarithromycin group may have obscured differences in clinical outcome between the two oral drugs.

Acknowledgments

We thank the study nurses for many hours spent interviewing patients and recording data and the clinicians at our study sites for identifying and obtaining consent from their patients.

An unrestricted grant to the Deseret Foundation by Bristol Myers Squibb supported this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Colice, G. L., M. A. Morley, C. Asche, and H. G. Birnbaum. 2004. Treatment costs of community-acquired pneumonia in an employed population. Chest 125:2140-2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dean, N. C., M. P. Silver, and K. A. Bateman. 2000. Frequency of specialty physician care in community acquired pneumonia. Chest 117:393-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dean, N. C., M. P. Silver, B. James, K. A. Bateman, C. J. Hadlock, and D. Hale. 2001. Decreased mortality following implementation of a treatment guideline for community-acquired pneumonia. Am. J. Med. 110:451-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Efron, B., and G. Gong. 1983. A leisurely look at the bootstrap, the jackknife, and cross-validation. Am. Stat. 1983:36-48. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Food and Drug Administration. 2004. Package insert for gatifloxacin and clarithromycin. U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Washington, D.C.

- 6.File, T. M., J. Garau, F. Blasi, C. Chidiac, K. Klugman, H. Lode, J. R. Lonks, L. Mandell, J. Ramirez, and V. Yu. 2004. Guidelines for empiric antimicrobial prescribing in community-acquired pneumonia. Chest 125:1888-1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fine, M. J., T. Auble, D. Yealy, B. H. Hanusa, L. A. Weissfeld, D. E. Singer, C. M. Coley, T. J. Marrie, and W. N. Kapoor. 1997. A prediction rule to identify low-risk pneumonia patients with community-acquired pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 336:243-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoenig, J. M., and D. M. Heisey. 2001. The abuse of power: the pervasive fallacy of power calculations for data analysis. Am. Stat. 55:19-24. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klein, J. P., and M. L. Moeschberger. 1997. Survival analysis. Springer Verlag, New York, N.Y..

- 10.Larsen, L. D. 1997. Functional status change across an episode of CAP. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 155:a726. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mandell, L. A., J. G. Bartlett, S. F. Dowell, T. M. File, D. M. Musher, and C. Whitney. 2003. Update of practice guidelines for the management of community-acquired pneumonia in immunocompetent adults. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. Clin. Infect. Dis. 37:1405-1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mandell, L. A., T. J. Marrie, R. F. Grossman, A. W. Chow, R. H. Hyland, et al. 2000. Canadian guidelines for the initial management of community-acquired pneumonia: an evidence based update by the Canadian Infectious Disease Society and the Canadian Thoracic Society. Clin. Infect. Dis. 31:383-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Niederman, M. S., L. A. Mandell, A. Anzueto, J. B. Bass, W. A. Broughton, G. D. Campbell, N. Dean, T. File, M. J. Fine, P. A. Gross, F. Martinez, T. J. Marrie, J. F. Plouffe, J. Ramirez, G. A. Sarosi, A. Torres, R. Wilson, and V. L. Yu. 2001. American Thoracic Society guidelines for the management of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 163:1730-1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niederman, M. S., J. S. McCombs, A. N. Unger, A. Kumar, and R. Popovian. 1998. The cost of treating community-acquired pneumonia. Clin. Ther. 20:820-837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suchyta, M. S., N. C. Dean, S. Narus, and C. J. Hadlock. 2001. Impact of a practice guideline for community-acquired pneumonia in an outpatient setting. Am. J. Med. 110:306-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ware, J. E., M. Kosinski, D. M. Turner-Bowker, and B. Gandek. 2004. How to score version 2 of the SF-12 health survey (with a supplement documenting version 1). Quality Metric, Inc., Lincoln, R.I.