Abstract

Nocardia species are gram-positive environmental saprophytes, but some cause the infectious disease nocardiosis. The complete genomic sequence of Nocardia farcinica IFM 10152 has been determined, and analyses indicated the presence of two different RNA polymerase β subunit genes, rpoB and rpoB2, in the genome (J. Ishikawa, A. Yamashita, Y. Mikami, Y. Hoshino, H. Kurita, K. Hotta, T. Shiba, and M. Hattori, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:14925-14930, 2004). These genes share 88.8% identity at the nucleotide level. Moreover, comparison of their amino acid sequences with those of other bacterial RpoB proteins suggested that the nocardial RpoB protein is likely to be rifampin (RIF) sensitive, whereas RpoB2 protein contains substitutions at the RIF-binding region that are likely to confer RIF resistance. Southern analysis indicated that rpoB duplication is widespread in Nocardia species and is correlated with the RIF-resistant phenotype. The introduction of rpoB2 by using a newly developed Nocardia-Escherichia coli shuttle plasmid vector and transformation system conferred RIF resistance to Nocardia asteroides IFM 0319T, which has neither RIF resistance nor rpoB duplication. Furthermore, unmarked rpoB2 deletion mutants of N. farcinica IFM 10152 showed no significant resistance to RIF. These results indicated the contribution of rpoB2 to RIF resistance in Nocardia species. Since this is the first example of genetic engineering of the Nocardia genome, we believe that this study, as well as our determination of the N. farcinica genome sequence, will be a landmark in Nocardia genetics.

Nocardia species are gram-positive environmental saprophytes, but some cause the infectious disease nocardiosis. Nocardia farcinica is thought to be the most important species from the viewpoint of multiple drug resistance and due to its recent isolation incidence in Japan (8) as well as in Europe (14, 20). Recently we determined the complete genomic sequence of a clinical isolate, N. farcinica IFM 10152, and deduced the molecular bases of virulence and multidrug resistance of this bacterium (7). Unexpectedly, the genome contained two different RNA polymerase (RNAP) β subunit genes, rpoB and rpoB2. rpoB is considered to be the major RNAP β subunit gene because it forms an operon with rpoC, encoding the RNAP β′ subunit, as is the case in many bacteria. On the other hand, rpoB2 is located 570 kb from rpoB and with no other RNAP subunit genes. rpoB and rpoB2 share 88.8% identity at the nucleotide level. Moreover, comparison of their amino acid sequences with those of other bacterial RpoB proteins suggests that the nocardial RpoB protein is likely to be sensitive to rifampin (RIF), whereas the RpoB2 protein contains substitutions at positions which result in RIF resistance in many bacteria (16). Based on these observations, we predicted that rpoB2 was capable of contributing to RIF resistance of N. farcinica IFM 10152 (7).

RIF remains a front-line drug for treatment of infectious diseases, especially tuberculosis. Resistance to RIF in clinical isolates is almost always due to point mutations in the rpoB gene. In contrast, Nocardia and related bacteria intrinsically possess a variety of RIF-inactivating enzymes (1, 12, 22, 23). However, there have been no reports of RIF resistance involving rpoB duplication, implying a novel resistance mechanism. To elucidate the contribution of rpoB2 to RIF resistance, we constructed an rpoB2 deletion mutant of N. farcinica IFM 10152 and introduced the wild-type rpoB2 into Nocardia asteroides IFM 0319T, which was sensitive to RIF and lacked rpoB duplication, using a newly developed Nocardia-Escherichia coli shuttle plasmid vector and transformation system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

All Nocardia strains were obtained from the Research Center for Pathogenic Fungi and Microbial Toxicoses, Chiba University, Japan. With the exception of type strains, all Nocardia strains were isolated from clinical specimens in Japan. For cloning experiments, E. coli JM109 was used as a host strain. pYUB12 (18) was provided by S. K. Das Gupta and used as the source of a 2.6-kb EcoRV-HpaI fragment containing the pAL5000 origin of replication (17). pIJ702 was used as the source of a 1.05-kb BclI fragment carrying the tsr gene of Streptomyces azureus (3). A 6.7-kb SphI fragment carrying rpoB2 was prepared from pKNL039_H03, a plasmid from the N. farcinica IFM 10152 ordered plasmid library (http://nocardia.nih.go.jp/). pK18mobsacB (15) was obtained from the National Institute of Genetics, Japan.

RIF resistance test.

Nocardia strains were incubated in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (BD Biosciences) at 37°C for 24 h. A loopful of the culture was streaked onto BHI agar plates containing 0, 5, 10, 25, 50, or 100 μg/ml of RIF. The plates were incubated at 37°C, and bacterial growth was scored after 24 and 48 h.

Transformation of Nocardia.

Nocardia strains were incubated in 10 ml of BHI broth for 18 to 24 h at 37°C. Cells were harvested, washed twice with 5 ml of ice-cold water, and then resuspended in 50 μl of ice-cold 10% glycerol. The suspension was transferred to a chilled electroporation cuvette (2-mm gap) and mixed with 0.3 to 0.5 μg of DNA. After pulsing at 12.25 kV/cm with an Electro Cell Porator 600 (BTX Inc.), the suspension was added to 900 μl of BHI broth and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. Cells were then plated onto BHI agar plates containing 50 μg/ml of thiostrepton or 25 μg/ml of neomycin and incubated for 2 to 3 days at 37°C.

DNA techniques.

For nucleotide sequencing, BigDye Terminator v3.1 cycle sequencing kits and a 3130 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems) were used in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. For Southern hybridization, the AlkPhos direct labeling and detection system (Amersham Biosciences) was used. PCR was carried out in 10-μl reaction mixtures with a KOD-Plus kit (TOYOBO). For screening of transformants by PCR, bacterial cells were used as the template (6). The PCR amplification program consisted of one cycle of 3 min at 98°C, followed by 30 cycles of 20 s at 98°C, 20 s at 58 or 60°C, and 20 s at 68°C, with a final extension step at 68°C for 5 min. The following PCR primers were used: rpoBcoreF, 5′-CCGCAGACCCTGATCAACATCC-3′; rpoBcoreR, 5′-TCATGCTCGAGGAACGGAATCATC-3′; NFrpoBF, 5′-ATCGGCCAGATCCTGGAAACCCAC-3′; NFrpoBR, 5′-CATCGCCCAGCACTCCATCTCAC-3′; rpoBWF, 5′-GACGTCGACAAGCGCGACACC-3′; rpoBWR, 5′-GATGATCGCGTCCTCGTAGTTGTG-3′; aph3IIaF, 5′-TGCTCCTGCCGAGAAAGTAT-3′; and aph3IIaR, 5′-AATATCACGGGTAGCCAACG-3′.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in the DDBJ database under accession numbers AB219431, AB243741, and AB243742.

RESULTS

Correlation between rpoB duplication and RIF resistance in Nocardia species.

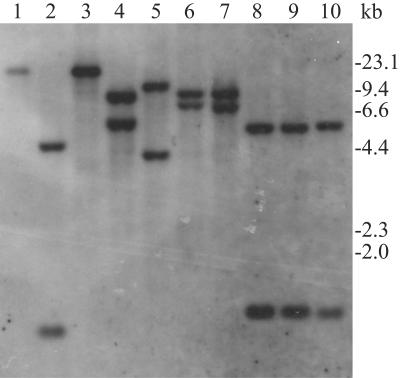

To analyze the occurrence of rpoB duplication in Nocardia species, total DNAs were extracted from 10 strains (including 3 type strains), digested with BamHI, and probed with a 437-bp fragment containing the C-terminal region of rpoB (Fig. 1). Since the nucleotide sequence of this region is identical to that of the corresponding region of rpoB2, two bands were expected to be detected in N. farcinica IFM 10152. The results showed that two bands were detected in 8 of 10 strains, suggesting the occurrence of rpoB duplication in these 8 strains. In contrast, single bands were obtained from N. asteroides IFM 0319T and IFM 10162, suggesting a lack of rpoB duplication. We also probed KpnI-digested total DNAs with the same fragment, with equivalent results (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Distribution of rpoB duplication among Nocardia strains. Total DNAs extracted from N. asteroides IFM 0319T (lane 1), N. asteroides IFM 10159 (lane 2), N. asteroides IFM 10162 (lane 3), N. brasiliensis IFM 0236T (lane 4), N. brasiliensis IFM 0406 (lane 5), N. brasiliensis IFM 10132 (lane 6), N. brasiliensis IFM 10160 (lane 7), N. farcinica IFM 0284T (lane 8), N. farcinica IFM 10125 (lane 9), and N. farcinica IFM 10152 (lane 10) were digested with BamHI and probed with a 437-bp fragment containing the C-terminal region of rpoB. The probe was prepared from the total DNA of N. farcinica IFM 10152 by PCR using the primers NFrpoBF and NFrpoBR.

Next we examined the RIF resistance of 10 strains. All strains with two bands were resistant to RIF (>25 μg/ml) with the exception of Nocardia brasiliensis IFM 0406 (Table 1). These observations suggested a correlation between rpoB duplication and RIF resistance.

TABLE 1.

Nocardia strains and their RIF resistance

| Species and strain/plasmid | RIF resistance (μg/ml) at:

|

Source | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h | 48 h | ||

| N. asteroides | |||

| IFM 0319T | <5 | <5 | Type strain (ATCC 19247T) |

| IFM 10159 | <5 | 25 | Japan clinical isolate |

| IFM 10162 | <5 | <5 | Japan clinical isolate |

| N. brasiliensis | |||

| IFM 0236T | 10 | 50 | Type strain (ATCC 19296T) |

| IFM 0406 | <5 | <5 | Japan clinical isolate |

| IFM 10132 | >100 | >100 | Japan clinical isolate |

| IFM 10160 | 10 | 50 | Japan clinical isolate |

| N. farcinica | |||

| IFM 0284T | >100 | >100 | Type strain (ATCC 3318T) |

| IFM 10125 | 25 | >100 | Japan clinical isolate |

| IFM 10152 | >100 | >100 | Japan clinical isolate |

| IFM 10152 ΔrpoB2 | <5 | <5 | This study |

| IFM 10152 ΔrpoB2/pNVrpoB2 | >100 | >100 | This study |

| N. asteroides | |||

| IFM 0319T/pNVrpoB2 | 50 | >100 | This study |

| IFM 0319T/pNV1.2 | <5 | <5 | This study |

Sequence analysis of the RIF-binding region of RpoB.

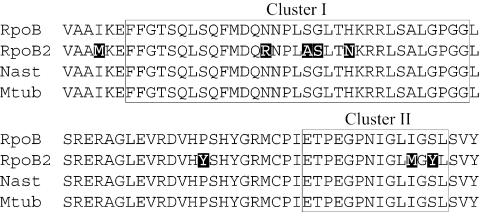

The above results strongly suggested that rpoB duplication is involved in RIF resistance in Nocardia species. This possibility could be confirmed by the introduction of rpoB2 into a strain with neither rpoB duplication nor RIF resistance. Southern hybridization analysis indicated that N. asteroides IFM 0319T is likely to have only one copy of rpoB in its genome (Fig. 1, lane 1). Subsequently, to estimate sensitivity to RIF, the RIF-binding region of rpoB was amplified from the IFM 0319T genome by PCR using the primers rpoBcoreF and rpoBcoreR, and its nucleotide sequence was determined. The deduced amino acid sequence of the rpoB gene of IFM 0319T was identical not only to that of IFM 10152 but also to that of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv, which has been shown to be sensitive to RIF (Fig. 2). Therefore, RpoB of IFM 0319T is considered to be sensitive to RIF.

FIG. 2.

Alignment of the RIF-binding regions of RNAP β subunits among N. farcinica IFM 10152 (RpoB and RpoB2), N. asteroides IFM 0319T (Nast), and M. tuberculosis H37Rv (Mtub). Amino acid substitutions are represented in reverse color. RIF-binding regions (clusters I and II) are boxed.

We also amplified the RIF-binding regions of rpoB and rpoB2 from the N. farcinica IFM 0284T genome by PCR using the primers rpoBWF and rpoBWR and determined their nucleotide sequences. Although a few nucleotide sequence differences in both rpoB and rpoB2 were found between IFM 10152 and IFM 0284, there were no deduced amino acid sequence differences between them (data not shown).

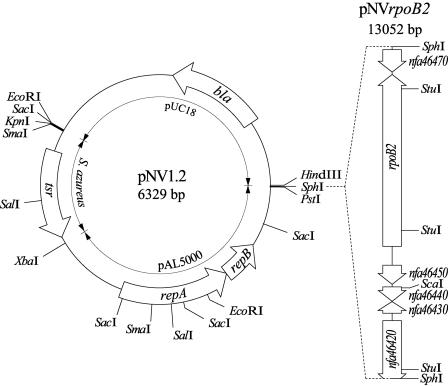

Introduction of rpoB2 into N. asteroides IFM 0319T.

Since very few vectors for use in Nocardia have been reported (21), we constructed a new Nocardia-E. coli shuttle plasmid vector employing pAL5000 (10), which is the most frequently used plasmid for making mycobacterial vectors. A newly developed vector, pNV1.2, was constructed by inserting a 2.6-kb EcoRV-HpaI fragment carrying the pAL5000 origin of replication (2) and a 1.05-kb BclI fragment containing the thiostrepton resistance gene (tsr) of Streptomyces azureus (3) into the HincII and BamHI sites of pUC18, respectively (Fig. 3). Next, a 6.7-kb SphI fragment containing rpoB2 was inserted into pNV1.2, resulting in pNVrpoB2 (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Restriction maps of pNV1.2 and pNVrpoB2. See text for details.

N. asteroides IFM 0319T was transformed with pNVrpoB2 or pNV1.2 by electroporation. Transformants carrying pNVrpoB2 were able to grow in the presence of RIF (100 μg/ml), but control strains carrying pNV1.2 were not (Table 1). This result indicated that rpoB2 acts as a determinant of RIF resistance in N. asteroides.

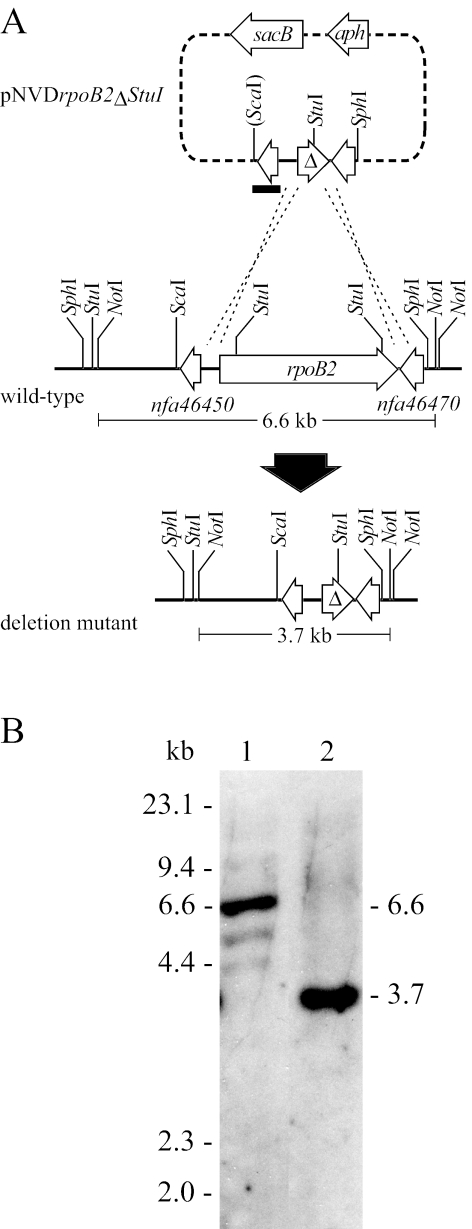

Construction of rpoB2 deletion mutants and their RIF resistance.

To determine the role of rpoB2 in RIF resistance in N. farcinica IFM 10152, we constructed an in-frame, unmarked deletion of rpoB2 by using a two-step selection method (Fig. 4A). A 4.9-kb ScaI-SphI fragment containing the wild-type rpoB2 was ligated to pUC19 that was digested with HincII and SphI. To make an in-frame deletion, the internal 2.9-kb StuI fragment of the wild-type allele was deleted by digestion of the resulting plasmid with StuI followed by self-ligation. A 2.0-kb XbaI-HindIII fragment carrying a deletion allele was cloned into pK18mobsacB (15), yielding pNVDrpoB2ΔStuI. After electroporation of pNVDrpoB2ΔStuI into IFM 10152, 95 neomycin-resistant clones were obtained. Of these, seven appeared to be legitimate single-crossover recombinants, which were distinguished from the rest by sensitivity to 10% sucrose and by the results of PCR analyses. One of the seven recombinants was grown in the presence of 10% sucrose, and sucrose-resistant and neomycin-sensitive clones were obtained. Six of the seven clones analyzed were confirmed to possess the expected genotype by Southern hybridization (Fig. 4B). To avoid cross-hybridization between rpoB and rpoB2, a 0.6-kb EcoRI fragment which contained the nfa46450 gene flanking rpoB2 was prepared from pNVDrpoB2ΔStuI and used as a probe (Fig. 4A). In ΔrpoB2 mutants, the 6.6-kb NotI fragment had disappeared and a 3.7-kb NotI fragment was detected instead, reflecting loss of the 2.9-kb StuI fragment (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Construction of the ΔrpoB2 mutant. A. Strategy for making an in-frame, unmarked deletion of rpoB2. See text for details. Δ indicates a deletion allele. The ScaI half-site generated after ligation of a 4.9-kb ScaI-SphI fragment containing rpoB2 to pUC19 digested with HincII and SphI is shown in parentheses. B. Southern hybridization analysis of a ΔrpoB2 mutant. NotI-digested total DNAs extracted from the wild-type strain (lane 1) and a ΔrpoB2 mutant (lane 2) were probed with a 0.6-kb EcoRI fragment containing nfa46450 (short black bar in panel A).

The wild-type strain was resistant to RIF at the lowest level of 100 μg/ml, whereas the ΔrpoB2 mutant was unable to grow in the presence of 5 μg/ml RIF (Table 1). In contrast, a ΔrpoB2 mutant carrying pNVrpoB2, which contained an intact rpoB2 gene (Fig. 3), recovered RIF resistance (Table 1). This result would rule out that the sensitivity of the ΔrpoB2 mutant to RIF was due to a mutation other than the deletion of rpoB2.

DISCUSSION

We demonstrated here the contribution of rpoB2 to RIF resistance in Nocardia species. There are at least two possible mechanisms by which rpoB2 gives rise to RIF resistance. The first is that RpoB2 may have reduced binding affinity for RIF due to amino acid substitutions and is capable of functioning in the presence of RIF instead of RpoB. This is the most commonly observed type of RIF resistance mechanism in many bacteria and can be confirmed by investigating the direct interaction between RpoB2 and RIF. The acquisition of antibiotic resistance due to mutations which cause structural changes in the target of the drug is often disadvantageous to bacteria in the absence of antibiotics (2, 13). For example, RIF-resistant rpoB mutants of M. tuberculosis show a decreased growth rate in vitro and in macrophages (11). However, since such disadvantages can be minimized by carrying both the wild-type rpoB and a mutant rpoB (e.g., rpoB2) in one genome, this may be an elaborate strategy to withstand RIF.

The second possible mechanism is that RNAP with RpoB2 may elicit expression of a latent RIF resistance gene which may be present in the genome. RIF mutations in rpoB have been shown to affect gene expression. For example, mutations in rpoB produce increased or decreased expression of genes controlled by a stringent promoter (24), and certain RIF mutations in rpoB have been shown to result in elevated antibiotic production in Streptomyces (4) and Bacillus subtilis (5). On the other hand, a variety of RIF-inactivating enzymes have been identified in Nocardia and related taxa, such as enzymes involved in phosphorylation (23), glycosylation (22), ribosylation (12), and monooxygenation (1). Indeed, N. farcinica IFM 10152 possesses a monooxygenase gene (nfa35380) whose deduced amino acid sequence is highly homologous to that of the RIF monooxygenase of Rhodococcus equi (1). Further study will be required to confirm the involvement of nfa35380 in the RIF resistance of N. farcinica IFM 10152. Yazawa et al. reported that N. farcinica strains probably inactivated RIF by decomposition (22). N. farcinica IFM 10152 also decolorizes RIF in prolonged culture (unpublished data), implying the participation of decomposition in RIF resistance. However, no growth was observed even when ΔrpoB2 mutants were cultured for 1 week in the presence of 5 μg/ml RIF (data not shown). These observations may support the second possibility in N. farcinica.

N. asteroides IFM 10159 was resistant to RIF only after 48 h, and N. brasiliensis IFM 0406 was sensitive to RIF. These observations may be due to the weak expression of rpoB2. Our preliminary experiments showed that the expression of rpoB2 was less than 1/10 that of rpoB (unpublished data). In IFM 0406, the expression of rpoB2 may be too weak to contribute to the RIF resistance of the host.

Southern analysis indicated that rpoB duplication is widespread in Nocardia strains and species (Fig. 1). rpoB duplication may not be a rare event in Nocardia and related taxa, because rpoB duplication has recently been found in Actinomadura sp. strain ATCC 39727 (19), which is closely related to Nocardia. The extra rpoB gene of ATCC 39727, rpoBR, was studied in connection with antibiotic production. The constitutive expression of rpoBR led to increased production of the glycopeptide antibiotic A40926 in a mutant resistant to RIF. In this context, it would be interesting to determine the effects of rpoB2 expression on the antibiotic productivity of N. asteroides IFM 0319T carrying pNVrpoB2.

Nocardia has interesting and important features because some species are known to produce antibiotics and aromatic compound-degrading or -converting enzymes. However, the genetic manipulation of this organism has been hampered by the lack of genetic tools. We showed here that the mycobacterial plasmid pAL5000 was capable of replicating in Nocardia species. This would facilitate faster progress in the molecular biology of Nocardia because a number of mycobacterial vectors may be available, with or without slight modification. We also demonstrated that the Nocardia genome can be modified by standard techniques. Since this is the first example of genetic engineering of the Nocardia genome, we believe that this study, as well as our determination of the N. farcinica genome sequence, will be a landmark in Nocardia genetics. However, the frequency of homologous recombination-mediated integration events obtained using a suicide plasmid was found to be very low. Only 7 of 95 recombinants appeared to be legitimate single-crossover recombinants. The rest would be generated by illegitimate recombination, because the aph gene was detected in all neomycin-resistant recombinants by PCR with the primers aph3IIaF and aph3IIaR (data not shown). A high degree of illegitimate recombination has been known to occur in slow-growing mycobacteria (9). It is necessary to develop a more efficient strategy for gene knockout in Nocardia.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. K. Das Gupta for pYUB12, Y. Mikami for Nocardia strains, K. Takeda and F. Saito for technical assistance, K. Ishino and Y. Hoshino for helpful discussion, K. Summers and N. Summers for help with the text, and K. Hotta and Y. Uehara for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by the Research for the Future Program of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (grant no. 00L01411) and by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture (grant no. 17019009).

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersen, S. J., S. Quan, B. Gowan, and E. R. Dabbs. 1997. Monooxygenase-like sequence of a Rhodococcus equi gene conferring increased resistance to rifampin by inactivating this antibiotic. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:218-221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andressen, D. I., and B. R. Levin. 1999. Persistence of antibiotic resistant bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2:489-493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bibb, M. J., M. J. Bibb, J. M. Ward, and S. N. Cohen. 1985. Nucleotide sequences encoding and promoting expression of three antibiotic resistance genes indigenous to Streptomyces. Mol. Gen. Genet. 199:26-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hu, H., Q. Zhang, and K. Ochi. 2002. Activation of antibiotic biosynthesis by specified mutations in the rpoB gene (encoding the RNA polymerase β subunit) of Streptomyces lividans. J. Bacteriol. 184:3984-3991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inaoka, T., K. Takahashi, H. Yada, M. Yoshida, and K. Ochi. 2004. RNA polymerase mutation activates the production of a dormant antibiotic 3,3′-neotrehalosadiamine via an autoinduction mechanism in Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 279:3885-3892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishikawa, J., N. Tsuchizaki, M. Yoshida, D. Ishiyama, and K. Hotta. 2000. Colony PCR for detection of specific DNA sequences in Actinomycetes. Actinomycetologica 14:1-5. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ishikawa, J., A. Yamashita, Y. Mikami, Y. Hoshino, H. Kurita, K. Hotta, T. Shiba, and M. Hattori. 2004. The complete genomic sequence of Nocardia farcinica IFM 10152. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:14925-14930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kageyama, A., K. Yazawa, J. Ishikawa, K. Hotta, K. Nishimura, and Y. Mikami. 2004. Nocardial infections in Japan from 1992 to 2001, including the first report of infection by Nocardia transvalensis. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 19:383-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalpana, G. V., B. R. Bloom, and W. R. Jacobs, Jr. 1991. Insertional mutagenesis and illegitimate recombination in mycobacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:5433-5437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Labidi, A., C. Dauguet, K. S. Goh, and H. L. David. 1984. Plasmid profiles of Mycobacterium fortuitum complex isolates. Curr. Microbiol. 11:235-240. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mariam, D. H., Y. Mengistu, S. E. Hoffner, and D. I. Andersson. 2004. Effect of rpoB mutations conferring rifampin resistance on fitness of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:1289-1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quan, S., H. Venter, and E. R. Dabbs. 1997. Ribosylative inactivation of rifampin by Mycobacterium smegmatis is a principal contributor to its low susceptibility to this antibiotic. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:2456-2460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reynolds, M. G. 2000. Compensatory evolution in rifampin-resistant Escherichia coli. Genetics 156:1471-1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schaal, K. P., and H.-J. Lee. 1992. Actinomycete infections in humans—a review. Gene 115:201-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schäfer, A., A. Tauch, W. Jager, J. Kalinowski, G. Thierbach, and A. Pühler. 1994. Small mobilizable multi-purpose cloning vectors derived from the Escherichia coli plasmids pK18 and pK19: selection of defined deletions in the chromosome of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Gene 145:69-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Severinov, K., M. Soushko, A. Goldfarb, and V. Nikiforov. 1993. Rifampicin region revisited. J. Biol. Chem. 268:14820-14825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Snapper, S. B., R. E. Melton, S. Mustafa, T. Kieser, and W. R. Jacobs. Jr. 1990. Isolation and characterization of efficient plasmid transformation mutants of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Mol. Microbiol. 4:1911-1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Snapper, S. B., L. Lugosi, A. Jekkelt, R. E. Meltont, T. Kiesert, B. R. Bloom, and W. R. Jacobs, Jr. 1988. Lysogeny and transformation in mycobacteria: stable expression of foreign genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:6987-6991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vigliotta, G., S. M. Tredici, F. Damiano, M. R. Montinaro, R. Pulimeno, R. di Summa, D. R. Massardo, G. V. Gnoni, and P. Alifano. 2005. Natural merodiploidy involving duplicated rpoB alleles affects secondary metabolism in a producer actinomycete. Mol. Microbiol. 55:396-412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wauters, G., V. Avesani, J. Charlier, M. Janssens, M. Vaneechoutte, and M. Delmee. 2005. Distribution of Nocardia species in clinical samples and their routine rapid identification in the laboratory. J. Bacteriol. 43:2624-2628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yao, W., Y. Yang, and J. Chiao. 1994. Cloning vector system for Nocardia spp. Curr. Microbiol. 29:223-227. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yazawa, K., Y. Mikami, A. Maeda, M. Akao, N. Morisaki, and S. Iwasaki. 1993. Inactivation of rifampin by Nocardia brasiliensis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:1313-1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yazawa, K., Y. Mikami, A. Maeda, N. Morisaki, and S. Iwasaki. 1994. Phosphorylative inactivation of rifampicin by Nocardia otitidiscaviarum. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 33:1127-1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou, Y. N., and D. J. Jin. 1998. The rpoB mutants destabilizing initiation complexes at stringently controlled promoters behave like “stringent” RNA polymerases in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:2908-2913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]