Abstract

A partial screen for genetic elements integrated into completely sequenced bacterial genomes shows more significant bias in specificity for the tmRNA gene (ssrA) than for any type of tRNA gene. Horizontal gene transfer, a major avenue of bacterial evolution, was assessed by focusing on elements using this single attachment locus. Diverse elements use ssrA; among enterobacteria alone, at least four different integrase subfamilies have independently evolved specificity for ssrA, and almost every strain analyzed presents a unique set of integrated elements. Even elements using essentially the same integrase can be very diverse, as is a group with an ssrA-specific integrase of the P4 subfamily. This same integrase appears to promote damage routinely at attachment sites, which may be adaptive. Elements in arrays can recombine; one such event mediated by invertible DNA segments within neighboring elements likely explains the monophasic nature of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi. One of a limited set of conserved sequences occurs at the attachment site of each enterobacterial element, apparently serving as a transcriptional terminator for ssrA. Elements were usually found integrated into tRNA-like sequence at the 3′ end of ssrA, at subsites corresponding to those used in tRNA genes; an exception was found at the non-tRNA-like 3′ end produced by ssrA gene permutation in cyanobacteria, suggesting that, during the evolution of new site specificity by integrases, tropism toward a conserved 3′ end of an RNA gene may be as strong as toward a tRNA-like sequence. The proximity of ssrA and smpB, which act in concert, was also surveyed.

The numerous bacterial and bacteriophage genome sequencing projects and accelerated research on pathogenicity islands have led to a new appreciation for how integrative genetic elements shape bacterial evolution (13, 14, 37, 40). Indeed, a picture of teeming horizontal genetic traffic at least within some groups of bacteria has emerged. The problem has been broken down for analysis by enumerating the elements within a genome or by monitoring a particular type of element to study its host distribution, various forms, and changes in site specificity. A complementary but less common approach—monitoring the flux of elements at a single attachment site—benefits from the focus on a standardized context for integration. In one study, occupation of the attachment site in the icd gene, which serves both elements e14 and phage 21, was monitored by PCR for a large and diverse set of Escherichia coli strains (52). Almost half the strains had one of these two elements at icd; however, novel elements, for which PCR primers specific for e14 or phage 21 would fail, might have been missed. The new wealth of bacterial genomic data offers the possibility of identifying novel elements and surveying a broad phylogenetic range of hosts. Here, attention is focused on one site found throughout bacteria and known to harbor genetic elements (6, 26, 30), the tmRNA gene (ssrA), and the traffic of integrative genetic elements at this site is monitored in available genomic data.

tRNA and tmRNA genes are the targets of the majority of classical integrases of the tyrosine recombinase family, and it may be that similarity to tRNA in sequence and structure at the 3′ end of tmRNA is what allows its gene to participate in this preference (55). The function of tmRNA also resembles that of tRNA in transferring an attached amino acid residue to a growing protein in the ribosome, although this is not mediated by an anticodon. More striking is its mRNA-like property. A tmRNA-internal reading frame switches places with mRNA that has caused a ribosome to stall, such that (i) translation resumes on tmRNA, tagging the nascent protein with a tmRNA-encoded peptide; (ii) the ribosome is freed at the stop codon of the tmRNA reading frame; and (iii) the tag directs the protein product to proteases for degradation (27). A single tmRNA gene has been found in every bacterial genome examined, although at least twice in evolution it has undergone a permutation event that switches the order of the front and back portions of the gene, with the result that the mature tmRNA is found in two pieces (17, 29). It is possible that integrative genetic elements contributed to these gene permutation events.

Among enterobacteria, the ssrA region has long been known for its variability. The region between smpB and nrdE in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium was found by comparison of genetic maps to have the largest of segments missing from Escherichia coli K-12, and later, by comparative hybridization analysis, to have a mosaic structure (3, 46). Complete genome sequences now show that this region houses a remarkable diversity of genetic elements, most of which have integrases that specify ssrA. A database of bacterial tRNA gene usage by integrases shows that bias for tmRNA genes is more significant than for any type of tRNA gene.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains.

Salmonella strains were generously provided by Robert Edwards (then at Urbana, Ill., now at Memphis, Tenn.), except for reference collection C, which was purchased from the Salmonella Genetic Stock Centre. Strains whose genomic data were analyzed are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains containing genetic elements described here

| Strain | Abbreviation | Elements in screen | Element in ssrA | Element in icd | Sequence accession no.a | smpB-ssrA distance (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proteobacteria (γ subdivision, enterobacteria) | ||||||

| Escherichia coli K-12 MG1655 | Ecok | 2 | + | e14 | NC_000913 | 214 |

| Escherichia coli O157:H7 EDL933 | Ecoo | 5 | + | None | NC_002655 | 109 |

| Escherichia coli O157:H7 Sakai | Ecos | 5 | + | None | NC_002695 | 119 |

| Escherichia coli E2348/69 | Ecoe | ND | + | None | AF297061;SC | 213 |

| Escherichia coli CFT073 | Ecoc | ND | + | Phage 21 | UW | 214 |

| Escherichia coli RS218 | Ecor | ND | + | Phage 21 | UW | 214 |

| Shigella flexneri 2a | Sfl | ND | + | None | UW | 214 |

| Shigella dysenteriae | Sdy | ND | ? | None | SC | 214 |

| Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis | Sen | ND | + | None | UIUC | ND |

| Salmonella enterica serovar Paratyphi A | Spa | ND | + | None | WUSTL | ND |

| Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi TY2 | Stit | ND | + | None | UW | 16,388 |

| Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi CT18 | Stic | 3 | + | None | NC_003198 | 16,386 |

| Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2 | Stm | 0 | + | None | NC_003197 | 16,980 |

| Salmonella bongori | Sbo | ND | ? | None | SC | 16,984 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Kpn | ND | + | None | WUSTL | 143 |

| Yersinia pestis CO92 | Ype | 1 | + | None | NC_003143 | 48 |

| Yersinia enterocolitica | Yen | ND | + | None | SC | 48 |

| Proteobacteria (γ subdivision, others) | ||||||

| Dichelobacter nodosus A 198 | Dno | ND | + | U20246 | ND | |

| Xanthomonas axonopodis subsp. citri | Xac | 3 | + | NC_003919 | 2,721 | |

| Xanthomonas campestris subsp. campestris | Xcc | 3 | + | NC_003902 | 2,817 | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 | Pae | 1 | − | NC_002516 | >50,000 | |

| Vibrio cholerae El Tor N16961 | Vch | 0 | + | NC_002505 | 68 | |

| Haemophilus influenzae Rd | Hin | 1 | − | NC_000907 | >50,000 | |

| Proteobacteria (α subdivision) | ||||||

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58 | Atu | 1 | − | NC_003304 | >50,000 | |

| Brucella melitensis 16M | Bme | 2 | − | NC_003317 | >50,000 | |

| Mesorhizobium loti MAFF303099 | Mlo | 4 | − | NC_002678 | >50,000 | |

| Ralstonia solanacearum GMI1000 | Rso | 3 | − | NC_003295 | >50,000 | |

| Sinorhizobium meliloti 1021 | Sme | 1 | − | NC_003047 | >50,000 | |

| Firmicutes (actinobacteria) | ||||||

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv | Mtur | 1 | − | NC_000962 | 966 | |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis CDC1551 | Mtuc | 1 | − | NC_002755 | 966 | |

| Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) | Sco | 4 | − | NC_003888 | 114 | |

| Firmicutes (Bacillales) | ||||||

| Bacillus halodurans C-125 | Bha | 1 | + | NC_002570 | 69 | |

| Bacillus subtilis 168 | Bsu | 1 | − | NC_000964 | 176 | |

| Staphylococcus aureus Mu50 | Sauu | 1 | + | NC_002758 | 90 | |

| Staphylococcus aureus MW | Sauw | 1 | + | NC_003923 | 90 | |

| Listeria innocua CLIP 11262 | Lin | 1 | − | NC_003212 | 10,788 | |

| Firmicutes (Lactobacillales) | ||||||

| Enterococcus faecalis V538 | Efa | 1 | − | TIGR | >50,000 | |

| Streptococcus pyogenes SF370 | Spy | 0 | − | NC_002737 | >50,000 | |

| Lactococcus lactis IL1403 | Lla | 2 | + | NC_002662 | 9,714 | |

| Cyanobacteria | ||||||

| Nostoc sp. strain PCC7120 | Nos | 1 | − | NC_003272 | >50,000 | |

| Synechococcus sp. strain WH8102 | Synw | ND | + | JGI | >50,000 | |

| Other bacteria | ||||||

| Deinococcus radiodurans R1 | Dra | 1 | − | NC_001263 | >50,000 |

References for sequence data: UW, University of Wisconsin (www.genome.wisc.edu); UIUC, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign (www.salmonella.org); WUSTL Washington University (genome.wustl.edu); TIGR, The Institute for Genome Research (www.tigr.org); JGI, Joint Genome Institute (www.jgi.doe.gov); and SC, Sanger Centre (www.sanger.ac.uk). Others are accession numbers from GenBank (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

Multigenome screen for integrated elements.

In July 2002, 62 complete bacterial genomes were available at GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and the Institute for Genome Research (TIGR; http://www.tigr.org), with gene annotations for tRNAs and for at least one member of the tyrosine recombinase family (considered a candidate integrase, even though many in the family are known to have other functions). Coordinates in these genomes for (i) 580 candidate integrase genes, (ii) 3,466 tRNA genes of assigned identity, and (iii) 62 tmRNA genes were taken from GenBank, TIGR, KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; http://www.genome.ad.jp), GtDB (Genomic tRNA Database; http://rna.wustl.edu/GtRDB), and the tmRNA website (http://www.indiana.edu/∼tmrna). Of the candidate integrase genes, 116 were within 5 kbp of a tRNA or tmRNA gene, whose sequence was then used as a query at either the TIGR or GenBank BLAST servers, against the genome of origin, with default parameters; for 59 of these, hits were obtained for terminal fragments that were not part of other tRNA genes. The catalytic domain sequences of these integrases were aligned manually as at the tyrosine recombinase website (http://mywebpages.comcast.net/domespo/trhome.html); at this stage, eight candidate elements were rejected because the integrase gene was found to be incomplete. All 51 genome segments identified this way are considered probable integrated elements and, along with other elements in prokaryotic RNA genes, are described further elsewhere (http://www.indiana.edu/∼interna).

In an attempt to reduce this set of integrases to the number of cases of evolutionary change in site specificity that they represent, pairwise evolutionary distances were evaluated for the aligned sequences with Blocks Substitution Matrix 62 (22). A cutoff distance score of 0.1 affected only very closely related integrase pairs with the same site specificity and reduced the set of integrases to 43. The set was reduced further by performing phylogenetic analysis with an alignment that included sequences of 45 additional unique integrases known to specify tRNA or tmRNA genes. The resulting tree (http://www.indiana.edu/∼interna) showed three more cases where an integrase pair (distance score as high as 0.96) appeared to descend from a common ancestor without changing specificity, further reducing the set of unique integrases to 40, distributed among 21 genomes that contained 1,336 tRNA and tmRNA genes. Bias in site specificity for each of the 23 types of tRNA and tmRNA genes is expressed as B = Fint/Fgene, or B < 0.5/40/Fgene when Fint = 0, where Fint is the frequency of use of the gene type among the 40 integrases and Fgene is the frequency of the gene type among the 1,336 tRNA and tmRNA genes. The statistical significance of the bias was evaluated as the tail (Pbias) of the binomial distribution for n = 40 and p = Fgene.

Phylogenetic analysis.

Alignments of the catalytic domain, corresponding to lambda integrase residues 202 to 345, of integrases and Cre recombinase (outgroup) were taken from the Tyrosine Recombinase Website, with some manual realignment and addition of integrases from GenBank or genome projects that were absent from the website (final alignments available at http://www.indiana.edu/∼interna). One hundred bootstrap subsamples of each alignment were constructed by SEQBOOT, distances for the subsamples were evaluated by using Blocks Substitution Matrix 62, trees were found by using FITCH with 10 jumblings, and majority-rule trees were taken by using CONSENSE (15).

Southern blots.

Salmonella cultures were grown overnight in 1.5 ml of Luria-Bertani broth. Cells were pelleted, resuspended in 600 μl of a 0.1-mg/ml concentration of proteinase K, and lysed by adding sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) to 0.5%. Nucleic acids were purified by extraction with phenol-CHCl3 and precipitation with isopropanol; a portion (15%, containing ca. 10 μg of genomic DNA) was digested to completion with 50 U of HhaI for 1.5 h. The DNA fragments were purified as described above, separated by electrophoresis in a 11-by-17-by-0.08-cm 5% polyacrylamide-Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) gel (with pre-32P-labeled PCR products in outer lanes as size markers), and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane in 0.5× TBE by using a Bio-Rad semidry electroblotter at 200 mA for 1 h. The membrane was treated with 0.4 N NaOH, rinsed in 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate), and incubated at 80°C for 1 h under vacuum at 50°C for 1 h in 4× SSC-1% SDS-10× Denhardt solution-0.1 mg of salmon sperm DNA/ml and at 50°C for 16 h after the addition of 5′-32P-AGGAATTTCGGACGCGGGTT (tmRNA nucleotides [nt] 323 to 342) to 0.3 μCi/ml. The membrane was rinsed for 5 min in 2× SSC-0.1% SDS at 23°C and autoradiographed. To identify bands derived from full-length ssrA, the membrane was stripped and rehybridized to 5′-32P-GCGAATGTAAAGACTGACTAAGCA (tmRNA nt 282 to 305). DNAs as small as ∼75 bp could have been detected, but none smaller than 260 bp were observed.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Overrepresentation of ssrA as an integration site.

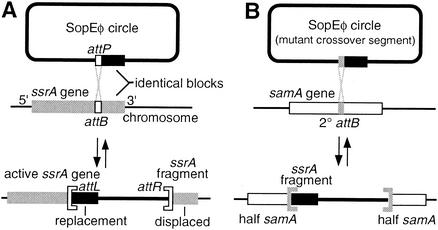

Integrative genetic elements in prokaryotes most often specify a chromosomal site (attB) within a tRNA or tmRNA gene; they necessarily disrupt the target gene upon integration but compensate by carrying within their own attachment site (attP) a replacement sequence that substitutes for the displaced 3′ segment of the target gene (9) (Fig. 1A). The identity between the replacement sequence and the displaced sequence is usually sufficient to be detected by homology-searching algorithms. Therefore, a complete prokaryotic genome sequence can be screened to find some of the integrated genetic elements by identifying each candidate integrase gene and, with the sequences of its flanking tRNA genes, searching the genome for the tRNA gene fragment that might be found on the other side of an element.

FIG. 1.

ssrA fragments produced by integration. (A) Elements that integrate into tRNA and tmRNA genes carry in their attP a replacement for the 3′ gene fragment that they displace, so that the gene is regenerated. Crossover typically occurs in a 7-bp segment at the gene internal end of the duplicated block. (B) When a secondary attB site is used, the gene fragment carried in attP appears ectopically. For uniformity, the attL and attR designations used in this article refer to tRNA gene orientation as in this diagram and may not match those of previous descriptions of the integrated elements.

A partial form of such a screen was performed on all complete bacterial genomes for which annotation of tRNAs and integrase homologs was available by searching for fragments only of tRNA genes within 5 kbp of a candidate integrase gene. This partial screen identified 51 likely elements that are described further at www.indiana.edu/∼interna. If not previously named, the elements are here given names with three parts: a three-letter abbreviation of the host species name (with a fourth letter to distinguish strains when necessary), a number representing the element length in kilobase pairs, and a single letter for the amino acid identity of the tRNA gene (using “Z” for selenocysteinyl-tRNA and “X” for tmRNA). There is no indication that any of the elements identified in the partial screen are false positives; however, many known elements in tRNA genes were missed. Some elements that specify crossover near the 3′ end of the tRNA gene were missed in cases where the small tRNA gene fragment was apparently damaged during integration (see section on “damage to attR” below). Many more elements were missed because this partial screen was limited to intact tRNA genes close to integrase genes; for approximately half of all integrated elements, the integrase gene is instead located at the distal end of the element (55). Downstream elements in a tandem array would also have been missed. These reasons for missing some elements should not have disproportionately represented genes of any particular tRNA identity.

The set of genomes surveyed shows reasonable phylogenetic distribution but some clumping in certain phyla. To correct for multiple occurrences of essentially the same integrase, phylogenetic analysis of the integrases from the 51 elements was used to reduce them to a set of 40 that presumably represent independent evolutionary events in which new site specificity arose. tRNA genes are completely enumerated in the 21 genomes containing these elements, allowing the frequency of adoption by integrases to be compared with the gene frequency for each tRNA type, with the null hypothesis that these two frequencies should be proportional. ssrA is overrepresented by more than sixfold as an integration site (Table 2), being specified by four of the 40 unique integrases despite accounting for only 1.6% of the tRNA genes surveyed in these genomes. Bias was slightly higher for the selenocysteinyl-tRNA gene but not with statistical significance because so few genes of this category were surveyed. Instead, bias for ssrA was far more statistically significant than for any tRNA gene category, although biases for tRNAArg genes and against tRNAMet and tRNAAla genes were notable.

TABLE 2.

Bias for tmRNA genes among unique integrases of multigenome screen

| tRNA | No. of genes | No. of unique integrases | Bias | Pbias | Integrase(s)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ala | 99 | 0 | <0.17 | >0.046 | |

| Arg | 116 | 8 | 2.30 | 0.020 | Dra18R, DLP12(Ecok), CPS-53(Ecok)=Ecoo9R=Sp16(Ecos), bIL309(Lla), Mlo105R, Rso16R, Sco14R, Sco21R |

| Asn | 46 | 1 | 0.73 | >0.1 | Ype36N |

| Asp | 52 | 0 | <0.32 | >0.1 | |

| Cys | 22 | 0 | <0.76 | >0.1 | |

| Gln | 49 | 0 | <0.34 | >0.1 | |

| Glu | 64 | 0 | <0.26 | >0.1 | |

| Gly | 94 | 6 | 2.13 | 0.059 | Bme15G∼Atu30G, Nos40G, Pae12G, Stic6G, Xac38G, Xcc31G |

| His | 26 | 0 | <0.64 | >0.1 | |

| Ile | 81 | 0 | <0.21 | 0.082 | |

| Initiator | 45 | 0 | <0.37 | >0.1 | |

| Leu | 125 | 4 | 1.07 | >0.1 | Bsu21L, Ecoo10L=SpLE5(Ecos), Rso42L∼φFlu(Hin), Stic11L, Lin39K, Xcc37K |

| Lys | 64 | 2 | 1.04 | >0.1 | |

| Met | 99 | 0 | <0.51 | >0.1 | |

| Phe | 32 | 2 | 2.09 | >0.1 | SymbiosisIsland(Mlo), Stic134F |

| Pro | 60 | 1 | 0.56 | >0.1 | Sco154P |

| Sel-Cys | 5 | 1 | 6.68 | >0.1 | Ecoo5Z=Ecos5Z |

| Ser | 92 | 4 | 1.45 | >0.1 | CP-933U(Ecoo)=Sp14(Ecos), Mlo38S, Rso41S, Xcc52S∼Xac6S |

| Thr | 74 | 4 | 1.81 | >0.1 | Bme8T, Efa25T, CP-933H(Ecoo)=Sp1(Ecos), Sme19T |

| Trp | 23 | 0 | <0.73 | >0.1 | |

| Tyr | 33 | 1 | 1.01 | >0.1 | pSLP1(Sco) |

| Val | 80 | 2 | 0.84 | >0.1 | Mlo45V, φRv2(Mtur)=Mtuc10V |

| tmRNA | 21 | 4 | 6.36 | 0.0036 | Bha35X, bIL286(Lla), SaGIm(Sauu)=vSa3mw(Sauw), Xac21X |

| Total | 1,336 | 40 |

Host strain (abbreviated as in Table 1) is in parentheses or included in the element name. The group representing the same evolutionary event of specificity change is suggested by (=) a distance score of <0.1 or by (∼) further phylogenetic analysis.

Includes initiator tRNAs and probably some misidentified tRNAIle genes.

Numerous elements at ssrA.

Among the annotated complete genomes, the partial screen revealed only five elements at ssrA; however, an additional eight could be found with closer scrutiny, having been missed for the reasons mentioned above (Table 3). Data from incompletely sequenced bacterial genomes and bacteriophages provide many additional examples. More still are found after relaxing criteria to include defective elements, for which either the distal attachment site cannot be identified or the integrase gene is defective or missing. Except with this last group, the phylogeny of the integrases is a useful starting point for comparing the elements.

TABLE 3.

ssrA-associated elements

| Elementa | Host (see Table 1) | Size (kbp) | Foundb | Endpoints determined (source or reference) | Encoded proteins and other notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P2 integrase subfamily | |||||

| Fels-2* | Stm | 33 | Ann | This study | |

| SopEφ* | Spa | NDc | Inc | This study | SopE |

| SopEφ* | Stic | 33 | Ann | 36 | At secondary attachment site samA |

| Stic34yif† | Stic | 34 | Ann | 41 | At yifB, relates to ssrA through SpaX and Stic9X |

| SpaX† | Spa | ND | Inc | ND | Unknown location, HP1-like |

| P4 integrase subfamily | |||||

| CP4-57* | Ecok | 22 | Ann | 45 | |

| EspCpi* | Ecoe | 15 | Def | 35 | Enterotoxin EspC |

| VPIφ* | Vch | 41 | Ann | 26 | Toxin-coregulated pilus |

| Stm27X* | Stm | 27 | Ann | This study | PTS system |

| Yen19X* | Yen | 19 | Inc | This study | attR uncertain; ssrA fragment not discerned |

| Ype11X* | Ype | 11 | Ann | This study | |

| Stit11X* | Stit | 11 | Ann | This study | Very similar to P4 |

| KpnX* | Kpn | ND | Inc | This study | |

| Sf14X* | Sfl | 4 | Def | This study | |

| LC3 integrase subfamily | |||||

| Bha35X | Bha | 35 | Scr | This study | Restriction-modification system, mother cell lysis |

| Phage T12* | Spy | ND | 34 | Erythrogenic toxin A | |

| φbIL286* | Lla | 42 | Scr | 10 | |

| CTXφ integrase subfamily | |||||

| Ecoc48X | Ecoc | 48 | Inc | This study | Lambda-like; same element in Ecor |

| Sme19T integrase subfamily | |||||

| Xac21X | Xac | 21 | Scr | This study | Second internal integrase gene not like Xcc9X |

| Unclassified integrases | |||||

| Oi108* | Ecoo | 22 | Ann | 43 | |

| Sp17* | Ecos | 24 | Ann | 40 | |

| Xcc9X | Xcc | 9 | Ann | This study | |

| Synw12X | Synw | 12 | Inc | This study | At non-tRNA-like 3′ end of permuted ssrA |

| vSa3mw† | Sauw | 14 | Scr | 2 | Enterotoxins L and C |

| SaGIm† | Sauu | 14 | Scr | 31 | |

| Missing integrase | |||||

| vrl | Dno | 27 | Inc | 6 | Associated with high-level pathogenicity |

| Stic9X | Stic | 9 | Def | This study | Fragment of Sic34yif, deletion by invertase |

| Ecok5X | Ecok | 5 | Def | This study | ATP-binding component of transport system |

| Sdy2X | Sdy | 2 | Def | This study | |

| Other interpolated regions | |||||

| flj-iro-vir-tct | Stm | 32 | Ann | 3 | Mosaic region, no att sites identified |

| hyl-agg | Stm | 17 | Ann | 25 | Upstream of ssrA, no att sites identified |

Asterisks and daggers denote especially closely related integrases within a subfamily.

Scr, found in partial multigenome screen; Ann, found in complete annotated genome with further scrutiny; Inc, found in incomplete or unannotated genomic data; Def, defective element.

ND, not determined.

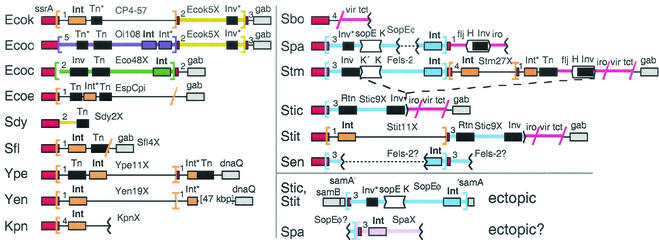

Enterobacteria have a particularly rich repertoire of elements using ssrA (Fig. 2) and not simply because more sequence data are available for the group. Integrases from at least four different subfamilies use enterobacterial ssrA.

FIG. 2.

Traffic at enterobacterial ssrA. Schematic diagram (not to scale) of genetic elements found in genome projects, with the host strain abbreviated at the left as in Table 1. Serovar Typhimurium is not an ancestor of serovar Typhi, but models one in which the indicated type of deletion (dashes) occurred, as detailed in Fig. 7B. Symbols: brackets, proposed att sites; slashes, junctions determined only as sequence similarity breakpoints; dotted lines, presumable connections between contigs; numbers 1 to 5, regions of similar (terminator) sequence (see Fig. 5); red, ssrA or its fragment; gray, chromosomal genes; white, invertible DNA segments, with arrowheads indicating directionality of crossover sites; black, genes promoting DNA rearrangements; Int, integrase (in boldface when intact); Inv, DNA invertase; Tn, transposase; Rtn, reverse transcriptase of retron; asterisk, degenerate gene. Other colors mark genetic elements classified by their integrases; blue and pink integrases are of the P2 subfamily, and orange integrases are of the P4 subfamily. Rather than a thick orange line, a thin black line is used to draw elements with P4 subfamily integrases to emphasize how diverse they are.

Uniform versus diverse groups of elements with related integrases.

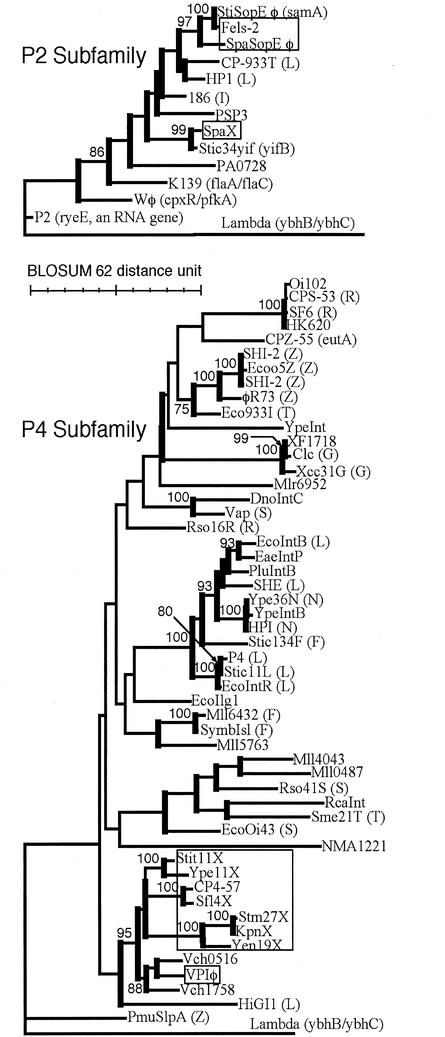

Phylogenetic analysis of integrases sorts them into several subfamilies; the two subfamilies most widely used at enterobacterial ssrA are presented in Fig. 3. The ssrA-specific integrases form a single clade within the P4 subfamily tree. The P2 subfamily tree has ssrA-specific integrases at two different positions, with intervening specificities for different tRNA genes, suggesting that such specificity may have arisen twice in the subfamily, although a single origin cannot be ruled out.

FIG. 3.

Phylogeny of P2 and P4 integrase subfamilies. Thick vertical bars mark groups with bootstrap support of ≥50%; support of ≥75% is specified. Integrases targeting ssrA are boxed. Known target genes of other integrases are given in parentheses, with the intergenic sites indicated with a slash and the tRNA genes indicated by the single-letter code for their amino acid identity, using “Z” for selenocysteinyl tRNA.

Broad examination of the entire group of genetic elements encoding P2 or P4 subfamily integrases (not just those specifying ssrA) reveals distinct characters; the group with P2 subfamily integrases has uniform similarity to the type phage P2, whereas the group with P4 subfamily integrases is very diverse, with great range in genome size and gene content, and no pairs sharing more than a few genes. Elements with P4 subfamily integrases can exist as tailed (P4) or filamentous (VPIφ) phages or not plausibly as a virion (611-kbp symbiosis island of Mesorhizobium spp.). This diversity is in keeping with the satellite character of the type phage P4; whereas its helper P2 is an independently functional phage, P4 carries only two genes for virion structure or morphogenesis and cannot form phage particles unless supplied with many genetic functions of P2 (33). Freedom from the burden of carrying structural genes seems to be a trend in this group of elements, which may have facilitated its diversification. At ssrA, these elements share no gene consistently other than that for the integrase.

Emergence of specificity for a secondary site.

SopEφ is a temperate phage first described as inducible from an epidemic serovar Typhimurium strain and morphologically similar to phage P2 (36). Although the genome of the type phage was not fully sequenced, the complete 33-kbp sequence of a closely related prophage was identified in data from S. enterica serovar Typhi CT18; it shares extensive homology with phage 186 of the P2 family and lies inserted into samA, a umuD homolog found on a virulence plasmid in some Salmonella strains but in the chromosome of serovar Typhi (Fig. 2). Despite inactivation of the samAB operon by separation from its promoter, the split portions have suffered no apparent coding deterioration, suggesting that SopEφ has inserted there fairly recently. The prophage has not replaced the 3′ gene fragment that it displaced; by this criterion, samA would not appear to be the primary attB for SopEφ. Moreover, a 45-bp 3′ fragment of ssrA is found at one flank of this SopEφ prophage, seemingly out of place, since samA is 1.7 Mbp from ssrA.

A nearly identical prophage is found (split among contigs) in sequence data from S. enterica serovar Paratyphi but is inserted into a different site, the ssrA gene itself (Fig. 2). At its other flank lies a 3′ ssrA fragment, apparently that displaced upon integration. This makes clear the origin of the ssrA fragment in the serovar Typhi prophage at samA; it is the still-remaining attP replacement sequence from the parental SopEφ, which specified ssrA. samA represents a secondary attachment site (Fig. 1B). Analysis of the attachment site sequences (see below) further illuminates the specificity switch; additional observations on SopEφ and its close relatives are reported in several of the following sections.

attL subsites within ssrA.

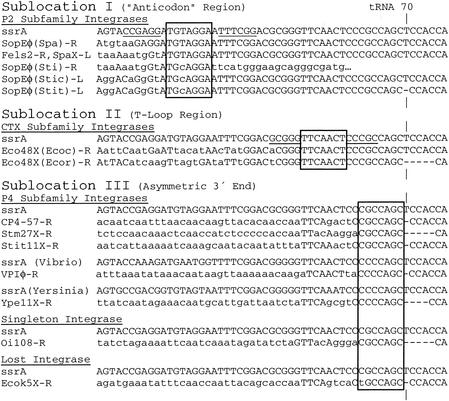

Most integrases specify tRNA or tmRNA genes, and three sublocations within these genes appear to serve as the site of attP-attB crossover (55). In three cases, the site has been precisely defined and maps to the 7 bp corresponding to the anticodon loop (sublocation I); it was suggested that that this coincidence reflects a preference of these integrases for symmetry of flanking segments (a known preference of lambda integrase), which is assured in DNA encoding stem-loop RNA (20, 42, 48). Examination of attL-attR identity blocks suggests that a second symmetrical site in tRNA genes is used for crossover, the 7 bp corresponding to the T-loop (sublocation II) (55). A third crossover sublocation occurs in an asymmetrical region at the far 3′ end of the gene (sublocation III) (1). Integrase phylogeny correlates with sublocation use; integrase subfamilies are found to use either the symmetrical sites or the asymmetric region exclusively (55).

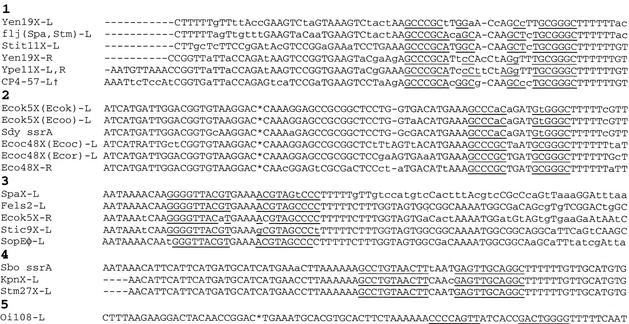

Integrases specifying enterobacterial ssrA use each of these sublocations (Fig. 4). The P2 subfamily integrases apparently use sublocation I, as they do in tRNA genes, which is notable because tmRNA contains no anticodon loop. The 9-bp segment (ATGTAGGAA) that occurs at the end of the attP-attB identity block is surrounded by 6-nt segments that can pair (allowing G-T pairs) in single-strand form, located in ssrA at a position that might have mimicked the symmetry at anticodon stem-loop tDNA during the evolution of site specificity by these integrases (Fig. 4). On the basis of this hypothesis, the 7-bp portion at the center of symmetry (underlined above) can be proposed as the crossover segment. The 8-bp sequence (ATGcAGGA) shared between the attL and attR of SopEφ in its ectopic samA site in serovar Typhi differs by only 1 bp (indicated by a lowercase letter) from the crossover segment proposed for ssrA, which both supports the proposal and explains the changed site specificity of this ectopic instance of SopEφ. Induction of SopEφ from samA in serovar Typhi would be predicted to produce a phage with a single-base-pair change (relative to SopEφ induced from ssrA in serovar Paratyphi) in the attP crossover segment that would tend to maintain the secondary samA specificity. It appears that there are two versions of SopEφ, specific for either ssrA or samA, whose important difference lies at a single-base-pair in the crossover segment.

FIG. 4.

Attachment site sequences. Suspected 7-bp crossover segments are boxed. Underlining indicates symmetry surrounding putative crossover segment. Lowercase, difference from the most comparable intact ssrA sequence; dash, base-pair missing (presumably due to damage inflicted during integration); ticks, tRNA position 70; -L or -R suffix, left or right end of the element (referring to Fig. 2).

Damage to attR.

Each of the elements with either a P4 subfamily integrase or the unassigned integrase of Oi108 appears to have suffered some damage at attR (dashes in Fig. 4), in the form of a small deletion (1 to 5 bp) extending downstream from a site in the ssrA sequence corresponding to tRNA position 70, in the acceptor stem. Since the source of the ssrA fragment at attR is the intact original host gene, this damage is presumably sustained during integration. Damage to attR at the same tRNA position is observed in some other elements with P4 subfamily integrases (e.g., SHE of Shigella flexneri, SHI-2 of Yersinia pestis, and 933I of E. coli O157:H7) but is especially common for those specifying ssrA. Integrated elements with damage at attR can still excise, but excision leaves the damage at the rejoined ssrA (26, 30, 45). This marks a boundary for the crossover segment. It also suggests that damage to attR may be an adaptive feature of these integrases. It would favor maintenance of the integrated element because excision would leave the host with damaged ssrA, whereas the excised element itself would be undamaged. Reciprocal damage at attL could be expected but is not observed; this might be explained by selection against strains with damaged ssrA genes, which would suggest a cost to the proposed adaptation through selection against some integrants. Another possibility is that the asymmetric intasome complex of attB, attP, integrase, and accessory proteins, formed during integration, can direct the damage to one side of one crossover segment.

The crossover site has not been mapped for any integrases that use sublocation III, and it is thus not yet clear whether they all specify the same position at tRNA and tmRNA gene 3′ ends or whether each uses a slightly different position within the region. For the clade of ssrA-specific integrases in the P4 subfamily, crossover can be inferred to occur between the rightmost end found among attL-attR identity blocks (55) and the damage site, shown in the 7-bp segment boxed in Fig. 4.

Limited set of conserved terminators at attL.

The diverse elements at enterobacterial ssrA carry a limited set of sequences adjacent to the tmRNA coding sequence (Fig. 5 and numbered 1 to 5 in Fig. 2). These sequences appear to encode factor-independent terminators, hairpins with GC-rich stems, followed by an oligo-U stretch; changes in the proposed stem sequences would often tend to preserve base pairing in the RNA. Especially for groups 3 to 5, the stem would be followed in either direction by oligo-U, suggesting that they might function as bidirectional terminators (49), protecting against the synthesis of antisense tmRNA and collisions between opposed transcription complexes in ssrA (although no obvious promoters aiming toward ssrA were detected). A given terminator sequence can be well-conserved among dissimilar elements. Knowledge of such conservation is important when assigning the junction of a genetic element based on a breakpoint in sequence similarity; element endpoints have sometimes been assigned downstream of a tRNA gene at which an internal position is the more likely endpoint.

FIG. 5.

Downstream flanks of attachment sites. The sequence immediately following the ACCA tail of the tmRNA gene or fragment is given. Underlining indicates suspected stems of factor-independent terminators. Lowercase, deviation from majority-rule consensus; asterisk, 75-bp block omitted for clarity; -L or -R suffix, left or right end of element (referring to Fig. 2); †, same for EspCpi-L and Sfl4X-L.

Terminator sequence homology can be stronger than the homology between ssrA and the short and damaged fragment left at attR by a P4 subfamily integrase. Homology searches with each of the terminator sequences were helpful for finding some attRs of this type; the best hits often abutted identifiable ssrA 3′ fragments in the vicinity of ssrA. A putative attR thus identified defines a defective element (Ecok5X) that may have once had a P4 subfamily integrase; a base pair change in the putative crossover segment of this attR may have rendered it inactive. An exception was the tentatively identified attR of Yen19X, where the sequence clearly related to ssrA is not found at a terminator sequence of group 1, although an int gene fragment is nearby, as often occurs at att sites.

Survey of ssrA gene fragments among Salmonella strains.

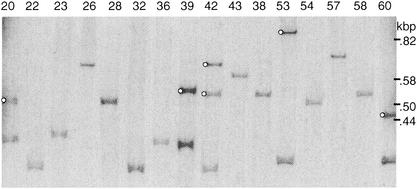

The Salmonella genus has been divided into eight subgroups (8); however, most current genome projects are from subgroup I, which contains many pathogenic strains. Each of these projects shows at least one 3′ ssrA fragment separate from the intact ssrA; that for S. paratyphi shows two. To determine the distribution of such fragments among the genus, genomic DNAs from 50 Salmonella strains were analyzed by Southern blotting, with a probe that would detect the P2-related prophages described here but none of the others (Fig. 6). These strains represented all eight subgroups of the genus, but most were from subgroup I (5, 7, 8). Entire ssrA genes were detected for all samples, but separate 3′ fragments were detected in only 16 strains of subgroup I (Table 4). Two strains had two copies of the fragment: S. enterica serovars Decatur and Paratyphi. The result for the latter was confirmed by its genome project.

FIG. 6.

ssrA fragments among Salmonella strains. A Southern blot was prepared from HhaI-digested genomic DNAs of the indicated strains of reference collection B (SARB) (7) and hybridized to a probe for the 3′ fragment of ssrA. Bands from tmRNA gene fragments (marked with circles) were subsequently identified by stripping the blot and rehybridizing to a probe for whole ssrA. Strain SARB42, with two ssrA fragments, is serovar Paratyphi A.

TABLE 4.

Survey of ssrA 3′ fragments among 50 Salmonella strains

| Salmonella subgroup(s) (no. of strains) | Strains |

|---|---|

| I, no fragment detected (22) | S. enterica serovar Typhi (cys trp); reference collection A, strains 23, 30, 41, 63; reference collection B, strains 4, 9, 21-23, 26, 28, 32, 36, 38, 43, 54, 57-59, 62; reference collection C, strain 1 |

| I, one fragment detected (14) | S. enterica serovar Enteritidis LK5; S. enterica serovar Pullorum SA 1686; reference collection A, strain 1; reference collection B, strains 1-3, 12, 15, 20, 39, 53, 60, 63, 71 |

| I, two fragments detected (2) | Reference collection B, strains 8 and 42 |

| II to VII, no fragment detected (12) | Reference collection C, strains 3-6, 8-12, 14-16 |

Element interactions in arrays.

The partly homologous prophages CTXφ and RS1 can exist as arrays at a site in the cco region of the large Vibrio cholerae chromosome and model three interesting interactions: (i) they have a helper-satellite relationship similar to that between P2 and P4, (ii) the satellite can regulate helper genes so as to favor helper phage production, and (iii) phage production by these prophages requires a replicative event crossing from one prophage to its neighbor in an array (11, 12). It not known whether the elements in arrays at ssrA have any of these sorts of interactions, but the following can be noted.

The different sizes of ssrA fragments left at attR by different elements impose a heirarchy of possible orders of integration. For example, elements with a P2 subfamily integrase leave larger ssrA fragments at attR, which can therefore serve as attB for elements with a P4-related integrase but not vice versa. For serovar Typhimurium, with the element order ssrA/Fels-2/Stm27X, the temporal order of integration is not deducible, but for serovar Typhi TY2, with the order ssrA/Stit11X/Stic9X, it can be deduced that Stit11X integrated more recently, since its attR should not serve as attB for a P2-like element (Fig. 2).

Damage found at attR in SopEφ of serovar Typhi TY2 and in Ecoc48X of E. coli RS218 is not expected to have been inflicted by their own integrases, since it is far from the crossover site (Fig. 4). Instead, the damage is consistent with what would occur from P4-like elements having historically integrated into, and then been excised from, these attR ssrA fragments.

The mosaic structure of genetic elements often inferred from comparative analysis (32, 50) must result from recombination in host cells. Proximity in arrays may provide a particularly favorable context for such events. The mechanism of such recombination is generally obscure, but a specific example can be deduced by comparison of arrays at enterobacterial ssrA; a deletion event promoted by invertible DNA segments in neighboring elements is described below.

Invertible DNA segments within elements at ssrA.

Many Salmonella strains are diphasic, i.e., capable of occasional switching between two flagellar types, which requires the second flagellar operon fljAB. Some strains in the diphasic lineage have reverted to the monophasic phenotype through loss of this operon. Analysis of one such hospital strain suggested that deletion was mediated by an insertion sequence (16). Instead, fljAB deletion likely occurred in an ancestor of serovar Typhi through the following interaction between elements arrayed at ssrA.

The whole flj-iro-vir-tct region of serovar Typhimurium (purple in Fig. 2) is a mosaic, with its portions occurring independently in different Salmonella strains (3); for example, in Salmonella bongori, the flj and iro portions are missing. On one end the region abuts elements integrated into ssrA, and on the other end it joins a site just upstream of the gene gab that is also a junction for elements in E. coli strains CFT073 and O157:H7. The junction at gab does not resemble the end of ssrA, so the mode of arrival of the region or its pieces is unclear; a defective form of the CP4-57 integrase gene at one end of the serovar Typhimurium unit suggests that at least the flj portion may have originated as an ssrA-specific integrative element. In any case, with its mosaic structure, no portion of which has been found in E. coli, the flj-iro-vir-tct region can be considered a composite genetic element. It contains the classical invertible DNA segment H, which controls expression of fljAB.

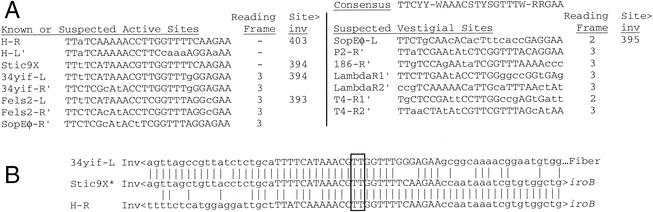

A second invertible segment is found 64 kbp away in the Fels-2 prophage at ssrA. Here a pair of open reading frames, K′ and 45′, aims convergently toward the homologous gene pair K and 45, which are tail fiber and fiber assembly genes found throughout the P2 phage family. A pair of convergently aimed 26-bp DNA-invertase crossover sites (24, 47) are found within K and at the upstream end of K′ (Fig. 7A), and this unit is flanked by a DNA invertase gene. By analogy with similar units in phages Mu and P1, this would appear to allow alternation between two forms of the virion tail fiber tip, so as to broaden the host range (51). Stic34yif, another P2-related element, has a similarly organized invertible segment whose action was documented by finding it in both orientations while sequencing the yifB region of serovar Typhi (41).

FIG. 7.

DNA invertase crossover sites. (A) Left (L) and right (R) designations are relative to Fig. 2 and may not match those of previous descriptions. The prime sign indicates that the complementary sequence is shown. Consensus, P2, lambda, and T4 (47), phage 186 (44), and H DNA (24) sites were published previously. The reading frame used by the genes that often read through these sequences is given, with the distance given in base pairs (Site>inv) from the center of the crossover site to the equivalent of the hin Met-115 codon in the neighboring invertase gene or pseudogene. (B) A large deletion in serovar Typhi relative to serovar Typhimurium was apparently mediated by DNA invertase (see Fig. 2). Vertical lines mark sequence identity between the deletion point at Stic9X of serovar Typhi and representatives of the predeletion parental endpoints (from Stic34yif of serovar Typhi CT18 and H of serovar Typhimurium); invertase would promote crossover at the dinucleotide center (boxed) of the capitalized recognition sequences. Inv, iro and K′ are neighboring genes (see Fig. 2).

In serovar Typhi CT18, the defective element Stic9X resides in place of Fels-2 at ssrA (Fig. 2). Stic9X is closely related to Stic34yif (99% identity over 7,900 bp) but with a retron inserted at one end and complete deletion of most of its other end. Comparison of extant sequences shows that fljAB was likely lost in an ancestor of serovar Typhi through precise recombination between the outermost crossover sites of H and an invertible segment in a P2-like prophage (Fig. 2 and 7B). Relative to the bacteriophage invertible segments, H has the opposite orientation of the 2-bp asymmetrical centers of the crossover sites, which would explain why the large intervening segment was deleted rather than inverted. SopEφ may have been relegated to the secondary samA attachment site in serovar Typhi due to exclusion by the defective element occupying the primary site at ssrA. However, contigs from S. enterica serovar Enteritidis suggest that Fels-2 prophages can exist as tandem duplicates at ssrA.

SopEφ has an especially close relationship with Fels-2, for gene order and sequence, but is distinguished by the presence of its namesake gene. sopE may play a role in pathogenesis (19, 57) and has been categorized as a “moron,” an extraneous phage gene with function differing from the surrounding virion structural genes; mechanisms of moron acquisition are obscure (21). sopE occurs at the same orientation and position as K′ does in Fels-2, next to a DNA-invertase pseudogene. An invertase crossover site occurs in the SopEφ tail-fiber gene K, at the same position as for Fels-2 and for several other phages (47). By tracing back from the invertase pseudogene for the corresponding distance for phage invertible segments, a second crossover site, somewhat degenerated, can be proposed within sopE (SopEφ-L in Fig. 7A). However, this site would be unusual in that protein coding reads through it in frame 2, and there is no evidence that SopE protein depends on inversion for expression (instead, it is found as a secreted protein at the size expected for the gene as sequenced), or that the element inverts. With a clearly debilitated invertase gene, loss of the recombinational enhancer, and degeneration of one of its crossover sites, the sopE unit may be a step in a progression from active bacteriophage invertible segments to cases such as P2, for which only the trace of a single crossover site can be found in the tail fiber gene.

Genetic elements at permuted tmRNA genes.

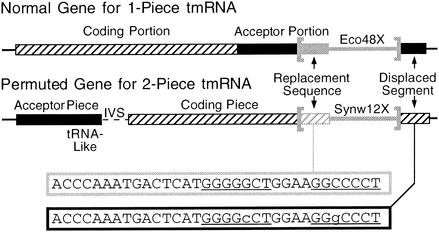

Two bacterial lineages, the α-proteobacteria and a group of marine cyanobacteria, have two-piece tmRNAs, due to a permuted form of the ssrA gene (17, 29, 54). In the permuted form, the tRNA-like portion that is normally found at the 3′ end of the gene is instead found at an internal position, and an intervening segment separates the two mature RNA pieces (Fig. 8). The rearrangement events leading to permutation occurred independently in the two lineages; it has been suggested that integrative genetic elements may have been involved.

FIG. 8.

Use of the 3′ end, but not the tRNA-like portion, of a permuted ssrA gene by a cyanobacterial genetic element. The usual order of ssrA portions (“coding” and “acceptor”) is switched in Synechococcus sp. strain WH8102; removal of an intervening segment (IVS) in precursor RNA produces a two-piece mature tmRNA (17). The genetic element Synw12X is integrated into the 3′ end of ssrA far from its tRNA-like portion (in the acceptor piece region). The duplicated 33-bp att sequences exhibit a compensatory base pair change in the underlined pairing P8.

An interesting mobile DNA is found at ssrA in the α-proteobacterium Rickettsia conorii (39). Normally, the intervening segment separating the mature tmRNA pieces is short; however, in R. conorii it is long, and it contains a copy of a palindromic repeat (termed RPE) found throughout the genome. RPEs occur most frequently in protein-coding genes, where not only does the RPE not interrupt the reading frame but the encoded peptide appears not to disrupt the structure of the surrounding protein; the mechanism of RPE distribution is unclear (38). In Rickettsia prowazekii and Rickettsia typhi the intervening segment in ssrA is also unusually long, and it may contain an unrecognized RPE; the RPEs that have been identified in R. prowazekii are less conserved than those of R. conorii and less palindromic. RPEs have not been identified outside the genus Rickettsia and are therefore of too limited a distribution to suggest that they might have been responsible for the α-proteobacterial ssrA permutation event.

Turning to the cyanobacterial lineage, the genetic element Synw12X can be discerned in genomic data from Synechococcus sp. strain WH8102, integrated at the end of the permuted ssrA (Fig. 8). It encodes an integrase of the AS subfamily, other members of which are responsible for programmed genomic deletions in Nostoc sp. strain PCC7120 (18). Rather than using the tRNA-like sequence that is normally at the 3′ end of ssrA and used by all other ssrA-specifying integrases, Synw12X has integrated into the novel 3′ end of the permuted gene and has produced a 33-bp duplication. The two bases that differ in the duplicate sequences constitute a compensatory base-pair change within the terminal stem-loop P8, which suggests that maintenance of this stem-loop provides some benefit to the cell. The position of this element in ssrA does not suggest a role in the events of permutation, aside from possibly having brought in the 3′-terminal sequence. Most likely, the specificity of Synw12X arose after ssrA had been permuted. This novel attachment site in a non-tRNA-like region shows that during the evolution of new site-specificity by integrases, tropism toward the conserved 3′ end of an RNA gene can be at least as strong as toward tRNA-like sequence. This conclusion is supported by the finding that phage P2 integrase specifies the 3′ end of a gene for an RNA (RyeE) unrelated to tRNA (53).

Genetic elements at ssrA in other bacteria.

Trends identified at enterobacterial ssrA are observed elsewhere. Reminiscent of the diversity of integrases specifying enterobacterial ssrA, the two Xanthomonas species with completed genomes have different elements at ssrA with integrases from different subfamilies. Like the elements with P4 subfamily integrases, other pairs of elements using ssrA share similar integrases but little else; one such pair is the phages T12 and bIL286 with hosts in the Lactobacillales (10, 34), and another is SaGIm and νSa3mw of Staphylococcus aureus. In several other S. aureus strains, such as N315, the integration site at ssrA is empty (2, 31).

smpB disposition at the upstream flank of ssrA.

smpB collaborates with ssrA: (i) it is required for association of tmRNA with the ribosome, (ii) disruption of either gene in E. coli has similar phenotypic effects, and iii) the gene products bind each other (28). In serovar Typhimurium, the phenotypic similarity between gene disruptions extends to pathogenic properties (4, 25). In E. coli, smpB is the upstream neighbor of ssrA and has the same orientation. Whether these two genes, which function together and may therefore coevolve, should be considered an operon is unclear. Transcription has not been closely studied; there may be some coexpression of the two genes in that no obvious terminator intervenes between them, but there should also be a high degree of independence to gene expression since ssrA is flanked closely by an apparently strong promoter and terminator. To complete the survey of genetic traffic at ssrA, the disposition of this upstream partner was examined. Both genes have been identified in single copies in all bacterial genomes examined. No smpB homolog has been identified in the chloroplast genomes that have ssrA (56); SmpB may be imported from the cytoplasm, or chloroplast tmRNA may function without SmpB or with a protein that is analogous but not homologous. Table 1 shows that the two genes are found in proximity in several but not all gram-positive and proteobacterial species, all with smpB upstream of ssrA and in the same orientation. It is not clear whether this linkage is ancient; linkage has not been observed for any species (including many others not listed in Table 1) outside the gram-positive and proteobacterial phyla.

smpB-ssrA is yet another subregion of the smpB-nrdE region that differs between Salmonella and Escherichia. In all Salmonella strains for which there are data, including S. bongori, smpB-ssrA distance is increased due to interpolation of a cluster of genes that are similar to the Salmonella pathogenicity island SPI4 and encode an ABC transporter system (25); the sequence of the cluster has not provided clues as to how it arrived there. This Salmonella-Escherichia difference suggests that any benefit to cells from smpB-ssrA juxtaposition is probably minimal.

Conclusions.

Simply searching with the tRNA gene sequences that flank integrase homolog genes revealed many new elements and their endpoints; it should become a routine part of prokaryotic whole-genome annotation.

Integrases have repeatedly evolved specificity for ssrA, more significantly so than for any type of tRNA gene. The reasons for ssrA bias are not known but can be expected to relate to the broader question of why integrases so frequently target genes for stable RNAs. It may have to do with structures that stable RNAs induce in their own genes, perhaps during transcription (23, 55). It will be interesting to see whether careful analysis of other integration sites will produce such a rich pattern of usage as found at ssrA. One point of contrast is the attachment site in the protein-coding gene icd; a genomic survey of enterobacterial icd (Table 1) agrees with a previous study (52), showing occupation only in some E. coli strains, by one of two elements that share essentially the same integrase (BLOSUM 62 distance score for catalytic domain = 0.41).

Mosaicism is pervasive among temperate bacteriophages (32, 50). An array of elements at a single site may provide an excellent context for the recombination events that create new hybrid elements. Here a site-specific recombination between neighbors in an array is described, but homologous and illegitimate recombination might also be favored by proximity in arrays.

Acknowledgments

I thank Rob Edwards for providing strains and other researchers for making their genome sequence data public.

This work was supported by NIH grant GM59881.

REFERENCES

- 1.Auvray, F., M. Coddeville, R. C. Ordonez, and P. Ritzenthaler. 1999. Unusual structure of the attB site of the site-specific recombination system of Lactobacillus delbrueckii bacteriophage mv4. J. Bacteriol. 181:7385-7389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baba, T., F. Takeuchi, M. Kuroda, H. Yuzawa, K. Aoki, A. Oguchi, Y. Nagai, N. Iwama, K. Asano, T. Naimi, H. Kuroda, L. Cui, K. Yamamoto, and K. Hiramatsu. 2002. Genome and virulence determinants of high virulence community-acquired MRSA. Lancet 359:1819-1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baumler, A. J., and F. Heffron. 1998. Mosaic structure of the smpB-nrdE intergenic region of Salmonella enterica. J. Bacteriol. 180:2220-2223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baumler, A. J., J. G. Kusters, I. Stojiljkovic, and F. Heffron. 1994. Salmonella typhimurium loci involved in survival within macrophages. Infect. Immun. 62:1623-1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beltran, P., S. A. Plock, N. H. Smith, T. S. Whittam, D. C. Old, and R. K. Selander. 1991. Reference collection of strains of the Salmonella typhimurium complex from natural populations. J. Gen. Microbiol. 137:601-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Billington, S. J., A. S. Huggins, P. A. Johanesen, P. K. Crellin, J. K. Cheung, M. E. Katz, C. L. Wright, V. Haring, and J. I. Rood. 1999. Complete nucleotide sequence of the 27-kilobase virulence related locus (vrl) of Dichelobacter nodosus: evidence for extrachromosomal origin. Infect. Immun. 67:1277-1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyd, E. F., F. S. Wang, P. Beltran, S. A. Plock, K. Nelson, and R. K. Selander. 1993. Salmonella reference collection B (SARB): strains of 37 serovars of subspecies I. J. Gen. Microbiol. 139:1125-1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyd, E. F., F. S. Wang, T. S. Whittam, and R. K. Selander. 1996. Molecular genetic relationships of the salmonellae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:804-808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell, A. M. 1992. Chromosomal insertion sites for phages and plasmids. J. Bacteriol. 174:7495-7499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chopin, A., A. Bolotin, A. Sorokin, S. D. Ehrlich, and M. C. Chopin. 2001. Analysis of six prophages in Lactococcus lactis IL1403: different genetic structure of temperate and virulent phage populations. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:644-651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis, B. M., H. H. Kimsey, A. V. Kane, and M. K. Waldor. 2002. A satellite phage-encoded antirepressor induces repressor aggregation and cholera toxin gene transfer. EMBO J. 21:4240-4249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis, B. M., and M. K. Waldor. 2000. CTXφ contains a hybrid genome derived from tandemly integrated elements. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:8572-8577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edwards, R. A., G. J. Olsen, and S. R. Maloy. 2002. Comparative genomics of closely related salmonellae. Trends Microbiol. 10:94-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eisen, J. A. 2000. Assessing evolutionary relationships among microbes from whole-genome analysis. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 3:475-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Felsenstein, J. 1995. PHYLIP (Phylogeny Inference Package), version 3.57c. Department of Genetics, University of Washington, Seattle.

- 16.Garaizar, J., S. Porwollik, A. Echeita, A. Rementeria, S. Herrera, R. M. Wong, J. Frye, M. A. Usera, and M. McClelland. 2002. DNA microarray-based typing of an atypical monophasic Salmonella enterica serovar. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2074-2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaudin, C., X. Zhou, K. P. Williams, and B. Felden. 2002. Two-piece tmRNA in cyanobacteria and its structural analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:2018-2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Golden, J. W., and H. S. Yoon. 1998. Heterocyst formation in Anabaena. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 1:623-629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hardt, W. D., L. M. Chen, K. E. Schuebel, X. R. Bustelo, and J. E. Galan. 1998. S. typhimurium encodes an activator of Rho GTPases that induces membrane ruffling and nuclear responses in host cells. Cell 93:815-826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hauser, M. A., and J. J. Scocca. 1992. Site-specific integration of the Haemophilus influenzae bacteriophage HP1. Identification of the points of recombinational strand exchange and the limits of the host attachment site. J. Biol. Chem. 267:6859-6864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hendrix, R. W., J. G. Lawrence, G. F. Hatfull, and S. Casjens. 2000. The origins and ongoing evolution of viruses. Trends Microbiol. 8:504-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henikoff, S., and J. G. Henikoff. 1992. Amino acid substitution matrices from protein blocks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:10915-10919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hou, Y. M. 1999. Transfer RNAs and pathogenicity islands. Trends Biochem. Sci. 24:295-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson, R. C., and M. I. Simon. 1985. Hin-mediated site-specific recombination requires two 26 bp recombination sites and a 60-bp recombinational enhancer. Cell 41:781-791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Julio, S. M., D. M. Heithoff, and M. J. Mahan. 2000. ssrA (tmRNA) plays a role in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium pathogenesis. J. Bacteriol. 182:1558-1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karaolis, D. K., J. A. Johnson, C. C. Bailey, E. C. Boedeker, J. B. Kaper, and P. R. Reeves. 1998. A Vibrio cholerae pathogenicity island associated with epidemic and pandemic strains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:3134-3139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karzai, A. W., E. D. Roche, and R. T. Sauer. 2000. The SsrA-SmpB system for protein tagging, directed degradation and ribosome rescue. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7:449-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karzai, A. W., M. M. Susskind, and R. T. Sauer. 1999. SmpB, a unique RNA-binding protein essential for the peptide-tagging activity of SsrA (tmRNA). EMBO J. 18:3793-3799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keiler, K. C., L. Shapiro, and K. P. Williams. 2000. tmRNAs that encode proteolysis-inducing tags are found in all known bacterial genomes: A two-piece tmRNA functions in Caulobacter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:7778-7783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kirby, J. E., J. E. Trempy, and S. Gottesman. 1994. Excision of a P4-like cryptic prophage leads to Alp protease expression in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 176:2068-2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuroda, M., T. Ohta, I. Uchiyama, T. Baba, H. Yuzawa, I. Kobayashi, L. Cui, A. Oguchi, K. Aoki, Y. Nagai, J. Lian, T. Ito, M. Kanamori, H. Matsumaru, A. Maruyama, H. Murakami, A. Hosoyama, Y. Mizutani-Ui, N. K. Takahashi, T. Sawano, R. Inoue, C. Kaito, K. Sekimizu, H. Hirakawa, S. Kuhara, S. Goto, J. Yabuzaki, M. Kanehisa, A. Yamashita, K. Oshima, K. Furuya, C. Yoshino, T. Shiba, M. Hattori, N. Ogasawara, H. Hayashi, and K. Hiramatsu. 2001. Whole genome sequencing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet 357:1225-1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lawrence, J. G., G. F. Hatfull, and R. W. Hendrix. 2002. Imbroglios of viral taxonomy: genetic exchange and failings of phenetic approaches. J. Bacteriol. 184:4891-4905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lindqvist, B. H., G. Deho, and R. Calendar. 1993. Mechanisms of genome propagation and helper exploitation by satellite phage P4. Microbiol. Rev. 57:683-702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McShan, W. M., Y. F. Tang, and J. J. Ferretti. 1997. Bacteriophage T12 of Streptococcus pyogenes integrates into the gene encoding a serine tRNA. Mol. Microbiol. 23:719-728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mellies, J. L., F. Navarro-Garcia, I. Okeke, J. Frederickson, J. P. Nataro, and J. B. Kaper. 2001. espC pathogenicity island of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli encodes an enterotoxin. Infect. Immun. 69:315-324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mirold, S., W. Rabsch, M. Rohde, S. Stender, H. Tschape, H. Russmann, E. Igwe, and W. D. Hardt. 1999. Isolation of a temperate bacteriophage encoding the type III effector protein SopE from an epidemic Salmonella typhimurium strain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:9845-9850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ochman, H., and N. A. Moran. 2001. Genes lost and genes found: evolution of bacterial pathogenesis and symbiosis. Science 292:1096-1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ogata, H., S. Audic, V. Barbe, F. Artiguenave, P. E. Fournier, D. Raoult, and J. M. Claverie. 2000. Selfish DNA in protein-coding genes of Rickettsia. Science 290:347-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ogata, H., S. Audic, and J. M. Claverie. 2001. Selfish DNA and the origin of genes. Science 291:252-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ohnishi, M., K. Kurokawa, and T. Hayashi. 2001. Diversification of Escherichia coli genomes: are bacteriophages the major contributors? Trends Microbiol. 9:481-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parkhill, J., G. Dougan, K. D. James, N. R. Thomson, D. Pickard, J. Wain, C. Churcher, K. L. Mungall, S. D. Bentley, M. T. Holden, M. Sebaihia, S. Baker, D. Basham, K. Brooks, T. Chillingworth, P. Connerton, A. Cronin, P. Davis, R. M. Davies, L. Dowd, N. White, J. Farrar, T. Feltwell, N. Hamlin, A. Haque, T. T. Hien, S. Holroyd, K. Jagels, A. Krogh, T. S. Larsen, S. Leather, S. Moule, P. O'Gaora, C. Parry, M. Quail, K. Rutherford, M. Simmonds, J. Skelton, K. Stevens, S. Whitehead, and B. G. Barrell. 2001. Complete genome sequence of a multiple drug resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi CT18. Nature 413:848-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pena, C. E., J. E. Stoner, and G. F. Hatfull. 1996. Positions of strand exchange in mycobacteriophage L5 integration and characterization of the attB site. J. Bacteriol. 178:5533-5536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perna, N. T., G. Plunkett III, V. Burland, B. Mau, J. D. Glasner, D. J. Rose, G. F. Mayhew, P. S. Evans, J. Gregor, H. A. Kirkpatrick, G. Posfai, J. Hackett, S. Klink, A. Boutin, Y. Shao, L. Miller, E. J. Grotbeck, N. W. Davis, A. Lim, E. T. Dimalanta, K. D. Potamousis, J. Apodaca, T. S. Anantharaman, J. Lin, G. Yen, D. C. Schwartz, R. A. Welch, and F. R. Blattner. 2001. Genome sequence of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157.:H7. Nature 409:529-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Portelli, R., I. B. Dodd, Q. Xue, and J. B. Egan. 1998. The late-expressed region of the temperate coliphage 186 genome. Virology 248:117-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Retallack, D. M., L. L. Johnson, and D. I. Friedman. 1994. Role for 10Sa RNA in the growth of lambda-P22 hybrid phage. J. Bacteriol. 176:2082-2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Riley, M., and A. Anilionis. 1978. Evolution of the bacterial genome. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 32:519-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sandmeier, H. 1994. Acquisition and rearrangement of sequence motifs in the evolution of bacteriophage tail fibres. Mol. Microbiol. 12:343-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smith-Mungo, L., I. T. Chan, and A. Landy. 1994. Structure of the P22 att site: conservation and divergence in the lambda motif of recombinogenic complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 269:20798-20805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Steiner, K., and H. Malke. 1997. Primary structure requirements for in vivo activity and bidirectional function of the transcription terminator shared by the oppositely oriented skc/rel-orf1 genes of Streptococcus equisimilis H46A. Mol. Gen. Genet. 255:611-618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Susskind, M. M., and D. Botstein. 1978. Molecular genetics of bacteriophage P22. Microbiol. Rev. 42:385-413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van de Putte, P., S. Cramer, and M. Giphart-Gassler. 1980. Invertible DNA determines host specificity of bacteriophage mu. Nature 286:218-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang, F. S., T. S. Whittam, and R. K. Selander. 1997. Evolutionary genetics of the isocitrate dehydrogenase gene (icd) in Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica. J. Bacteriol. 179:6551-6559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wassarman, K. M., F. Repoila, C. Rosenow, G. Storz, and S. Gottesman. 2001. Identification of novel small RNAs using comparative genomics and microarrays. Genes Dev. 15:1637-1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Williams, K. P. 2002. Descent of a split RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:2025-2030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Williams, K. P. 2002. Integration sites for genetic elements in prokaryotic tRNA and tmRNA genes: sublocation preference of integrase subfamilies. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:866-875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Williams, K. P., and D. P. Bartel. 1998. The tmRNA Website. Nucleic Acids Res. 26:163-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wood, M. W., R. Rosqvist, P. B. Mullan, M. H. Edwards, and E. E. Galyov. 1996. SopE, a secreted protein of Salmonella dublin, is translocated into the target eukaryotic cell via a sip-dependent mechanism and promotes bacterial entry. Mol. Microbiol. 22:327-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]