Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is the dominant pathogen causing chronic respiratory infections in cystic fibrosis (CF). After an initial phase characterized by intermittent infections, a chronic colonization is established in CF upon the conversion of P. aeruginosa to the mucoid, exopolysaccharide alginate-overproducing phenotype. The emergence of mucoid P. aeruginosa in CF is associated with respiratory decline and poor prognosis. The switch to mucoidy in most CF isolates is caused by mutations in the mucA gene encoding an anti-sigma factor. The mutations in mucA result in the activation of the alternative sigma factor AlgU, the P. aeruginosa ortholog of Escherichia coli extreme stress sigma factor σE. Because of the global nature of the regulators of mucoidy, we have hypothesized that other genes, in addition to those specific for alginate production, must be induced upon conversion to mucoidy, and their production may contribute to the pathogenesis in CF. Here we applied microarray analysis to identify on the whole-genome scale those genes that are coinduced with the AlgU sigmulon upon conversion to mucoidy. Gene expression profiles of AlgU-dependent conversion to mucoidy revealed coinduction of a specific subset of known virulence determinants (the major protease elastase gene, alkaline metalloproteinase gene aprA, and the protease secretion factor genes aprE and aprF) or toxic factors (cyanide synthase) that may have implications for disease in CF. Analysis of promoter regions of the most highly induced genes (>40-fold, P ≤ 10−4) revealed a previously unrecognized, putative AlgU promoter upstream of the osmotically inducible gene osmE. This newly identified AlgU-dependent promoter of osmE was confirmed by mapping the mRNA 5′ end by primer extension. The recognition of genes induced in mucoid P. aeruginosa, other than those associated with alginate biosynthesis, reported here revealed the identity of previously unappreciated factors potentially contributing to the morbidity and mortality caused by mucoid P. aeruginosa in CF.

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is the most common lethal genetic disorder among Caucasians, with a carrier frequency of 1 in 25 individuals (62). The principal causative agent of morbidity and mortality in CF is the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa (26). Pseudomonas infections in CF follow a characteristic course. The initial intermittent colonization of the CF lung (12) is believed to occur by infection with bacteria acquired from the environment. A more-or-less permanent chronic colonization is established upon conversion of P. aeruginosa to the mucoid phenotype (35, 48). As a result, mucoid P. aeruginosa is isolated from >90% of all CF patients (21). Infections with mucoid P. aeruginosa are associated with heightened inflammation, tissue destruction, and declining pulmonary function (7, 36). It has been recognized that the establishment of chronic mucoid P. aeruginosa colonization correlates with a poor prognosis for the CF patient (26, 35, 48).

The most overt characteristic of the mucoid phenotype is the production of a thick mucopolysaccharide layer consisting of the exopolysaccharide alginate (26). Conversion to mucoidy results from mutations that free the stress response sigma factor AlgU (42, 43), the P. aeruginosa ortholog of E. coli σE (66)—also known as AlgT (18)—from negative regulation by the anti-sigma factor mucA (10). AlgU induces the production of the exopolysaccharide alginate via activation of the promoter for the alginate biosynthetic operon headed at its 5′ end by the algD gene (16, 17, 22). The alternative sigma factor AlgU has been shown to have additional roles other than activation of the alginate biosynthesis pathway (20, 54). For example, AlgU directs transcription of the gene encoding the main heat shock sigma factor RpoH (54), as well as a number of products situated around the genome, including factors that may protect the bacterium from stress, such as osmC (20). Among genes previously shown to belong to the AlgU sigmulon (20) are a number of products with proinflammatory potential, including lipoproteins that provoke the host inflammatory response via Toll-like receptor signaling (1) and that induce production of interleukin-8 (IL-8) by human macrophages (20).

Previous studies have relied on classical transcript mapping (56) or a bioinformatics approach, involving identification of recognizable AlgU consensus promoter sequences in the P. aeruginosa genome followed by transcriptional mapping of individual promoters (20). In order not only to identify the immediate genes controlled by AlgU (collectively termed the “AlgU sigmulon”) (20), but also to uncover all of the genes in P. aeruginosa that are induced upon conversion to mucoidy or otherwise affected by AlgU activation, we carried out a whole-genome microarray analysis comparing global gene expression profiles in isogenic mucoid and nonmucoid P. aeruginosa strains. We found that a specific subset of P. aeruginosa virulence factors is induced upon conversion to mucoidy. These and additional observations may have implications for understanding the worsening of disease in CF patients upon conversion to mucoidy in P. aeruginosa. Our studies also further expand the AlgU sigmulon, increasing the number of known mapped AlgU (σE) promoters.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

P. aeruginosa PAO381 (PAO1 leucine auxotroph) and its mucoid derivatives PAO578I (mucA22) and PAO578II (mucA22 sup-2) have been described previously (8, 23). The nonmucoid strain PAO6865 (algU::Tcr) is derived from PAO578II (9). For RNA isolation, strains were cultured shaking at 37°C overnight in Luria broth (LB). One milliliter of the overnight culture was used to inoculate 100 ml of LB with 0.3 M NaCl (PAO578II and PAO6865) or without salt supplement (PAO381 and PAO578I) for a starting density equal to that of a saturated culture diluted 1:100 and grown for 4 h at 37°C to a mid-log optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.5. Growth curves were determined up to the 4-h harvest and were identical for mucoid and nonmucoid strains.

Genomic searches.

PAO1 genomic sequence was obtained from the Pseudomonas Genome Project (www.pseudomonas.com) (60). Data were imported for analysis by MacVector sequence analysis software (version 7.0; Eastman Kodak Co.). A subsequence search corresponding to the AlgU consensus (GAACTT-N16/17-TCCAA) was carried out, allowing for up to four substitutions to determine potential AlgU promoter sites in the genome. Additional information was obtained from the PseudoCAP annotation project (www.pseudomonas.com).

Primer design and DNA methods.

The 16-mer primers GAACTGCACGACGAGC and CCTCCGTAAGGAAGCG were generated approximately 400 bp upstream and downstream of the osmE promoter. These primers were used in a PCR to generate a 0.8-kb fragment from total genomic PAO1 DNA to serve as a sequencing template. A 22-mer primer, GGGTTGCCATCACGAACAGTGC, was designed 60 bp downstream of the suspected AlgU promoter site and oriented to extend back towards the putative promoter to generate a transcript by using reverse transcriptase in primer extension analyses as well as to sequence the promoter region by using a 33P sequencing kit (Amersham, Piscataway, N.J.). Controls (algD and oprF) for these studies have been described previously (20).

RNA isolation and microarray analysis.

For primer extension analysis RNA was isolated over a CsCl cushion as described previously (20). For microarray analysis and primer extension, RNA was isolated with TRIzol (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, Calif.) and Qiagen RNeasy (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.) according to the method described by Lory et al. (http://cfgenomics.unc.edu/protocols_rna_prep.htm). Accordingly, two 35-ml aliquots were taken from the 100-ml culture with an OD600 of 0.5 and processed in parallel. Cultures were pelleted and resuspended in TRIzol reagent by vortexing. Samples were lysed by sonication for 10 s and incubated at room temperature for 5 min. Following chloroform extraction, RNA was precipitated with isopropanol. RNA was pelleted, washed with 70% ethanol, and dried in a vacuum chamber. RNA was resuspended in water and treated with DNase (RQ1; Promega, Madison, Wis.) at 37°C for 1 h. Protein and nucleotides were removed by phenol-chloroform extraction, and RNA was precipitated in 1 volume of isopropanol. Pelleted RNA was resuspended in water, and like samples were combined. The quantity and purity of RNA were determined by OD260/280 spectrometry. tRNA was removed by following the RNeasy (Qiagen) RNA extraction protocol. Samples were eluted with 30 μl of water, and quantity was determined by spectrometry.

Labeled cDNA was generated according to the protocol for the Affymetrix (Santa Clara, Calif.) Pseudomonas microarray chip. cDNA was synthesized by annealing random primers (Invitrogen) to purified RNA and extended with SuperScript II (Invitrogen). Transcripts corresponding to Bacillus subtilis genes dap, thr, phe, lys, and trp were spiked into the cDNA synthesis reaction mixture as a control to monitor cDNA synthesis, labeling, hybridization, and staining efficiency (courtesy of Steve Lory, Harvard Medical School). RNA was removed by addition of 1 N NaOH and incubation at 65°C for 30 min. The reaction was neutralized with 1 N HCl, and cDNA was purified with a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen).

Yields were quantified and cDNA was fragmented with 0.6 U of DNase I (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) per μg of cDNA for 10 min at 37°C, followed by heat inactivation. Verification of cDNA fragmentation between 50 and 200 bases was confirmed by running samples on RNA 6000 Nano LabChip (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, Calif.) analyzed with an Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer. Fragmented cDNA was terminally labeled with biotin-ddUTP (Enzo BioArray terminal labeling kit; Affymetrix) for 30 min at 37°C.

GeneChip P. aeruginosa genome array chips (Affymetrix) were hybridized overnight at 50°C in the presence of nonspecific DNA and control B2 oligonucleotide (Affymetrix). The chips were washed, stained, and scanned the following day according to the steps of the Affymetrix Microarray Suite software, version 5.0, for the Pseudomonas chip on an Affymetrix GeneChip fluidics station. Chips were first stained with ImmunoPure streptavidin (Pierce Chemical, Rockford, Ill.), followed by biotinylated antistreptavidin goat antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, Calif.), and finally by R-phycoerythrin-streptavidin (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.). Chips were scanned on an Affymeterix probe array scanner. The results from three independent identical experiments were merged for each strain. The merged data were used for subsequent comparisons and assessed with Genomax (InforMax, Bethesda, Md.) and Microsoft Excel with Student's t test according to the method of Arfin et al. (3). The combined fourfold cutoff value and P value of ≤0.001 for inclusion in Tables 2 and 3 have been set arbitrarily high to minimize reporting of false positives. We point out that additional statistical tests (4, 40) can be applied to these data sets to glean additional information as necessary. The original raw data files have been deposited in the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Therapeutics, Inc.-Genomax shared workspace (http://cfgenomics.unc.edu/supplemental_data/geno_share.htm). Pertinent information on raw data containing hybridization results for specific oligonucleotide sets and confidence intervals for gene expression is available in that database.

TABLE 2.

Microarray analysis of global gene expression in mucoid P. aeruginosa strain PAO578I (mucA22) compared to its nonmucoid parent, PAO381 (mucA+)a

| Description (gene)b | Identification | Fold activation | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Toxins/toxin secretion | |||

| Alkaline metalloproteinase (aprA) | PA1249 | 9 | 8E-04 |

| 3-Oxoacyl-[acyl carrier protein] synthase III FabH2 | PA3333 | 9 | 2E-04 |

| Elastase (lasB) | PA3724 | 8 | 3E-05 |

| Alkaline protease secretion protein (aprF) | PA1248 | 8 | 3E-06 |

| Hydrogen cyanide synthase (hcnC) | PA2195 | 6 | 1E-03 |

| Hydrogen cyanide synthase (hcnA) | PA2193 | 6 | 2E-04 |

| Phospholipase accessory protein (plcR) | PA0843 | 4 | 1E-03 |

| Alkaline protease secretion protein (aprE) | PA1247 | 4 | 4E-05 |

| Membrane proteins/transport | |||

| Probable binding protein component of ABC transporter | PA0203 | 11 | 4E-04 |

| Hypothetical membrane protein | PA0702 | 8 | 9E-04 |

| Probable outer membrane efflux protein | PA3521 | 7 | 2E-04 |

| Probable outer membrane protein | PA2760 | −5 | 1E-05 |

| Enzymes and unknown | |||

| Probable short chain dehydrogenase | PA3330 | 64 | 4E-07 |

| Unknown | PA3329 | 38 | 8E-05 |

| Probable nonribosomal peptide synthetase | PA2302 | 10 | 3E-04 |

| Probable aminopeptidase | PA2939 | 8 | 7E-04 |

| Probable FAD-dependent monooxygenase | PA2587 | 6 | 3E-04 |

| Probable FAD-dependent monooxygenase | PA3328 | 6 | 9E-04 |

| Probable nonribosomal peptide synthetase | PA3327 | 5 | 4E-04 |

| Probable nonribosomal peptide synthetase | PA2305 | 4 | 1E-03 |

| Motility and attachment | |||

| Type 4 fimbrial biogenesis protein (fimT) | PA4549 | 9 | 1E-04 |

| Type 4 fimbrial biogenesis protein (pilM) | PA5044 | −4 | 5E-04 |

| Transcriptional regulation | |||

| Probable transcriptional regulator | PA2681 | 5 | 2E-05 |

| Metabolism | |||

| Cytochrome P450 | PA3331 | 9 | 4E-04 |

| Probable cytochrome c | PA1555 | −4 | 2E-04 |

| Probable cytochrome c oxidase subunit | PA1556 | −4 | 9E-06 |

| Cytochrome c551 peroxidase (ccpR) | PA4587 | −4 | 3E-04 |

Values represent higher (positive) or lower (negative) expression in the mucoid strain than in the nonmucoid strain. For a fold difference of ≥4-fold, P ≤ 0.001.

Only genes with known or homology-based proposed function (annotated in the P. aeruginosa genome) are included. PA3329 (unknown) is included to highlight its induction along with that of the adjacent genes suggestive of a putative operonic structure.

TABLE 3.

Microarray analysis of ECF sigma factor AlgU (P. aeruginosa σE)-dependent gene expression in P. aeruginosaa

| Description (gene) | Identification | Fold activationb | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Previously identified AlgU-dependent genes | |||

| Hypothetical membrane protein (slyB [ycfJ]) | PA3819 | 56 | 2E-04 |

| Hypothetical lipoprotein (lptA) | PA1592 | 35 | 5E-06 |

| Osmotically inducible protein (osmC) | PA0059 | 24 (91) | 4E-04 |

| GDP-mannose 6-dehydrogenase (algD) | PA3540 | 7 | 2.4E-02 |

| Hypothetical protein (asmD3) | PA3902 | 4 | 1E-03 |

| Hypothetical protein (asmD2) | PA3952 | 3 | 6.5E-02 |

| Hypothetical protein (asmB2) | PA0856 | 2 | 1.0E-02 |

| Sigma factor (rpoH) | PAO376 | 1 | 5.3E-01 |

| Outer membrane protein (oprF) | PA1777 | 1 | 7.1E-01 |

| Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase (lptB) | PA3262 | 1 | 2.3E-01 |

| Expression change ≥4-fold (P ≤ 0.001) | |||

| Membrane proteins | |||

| Osmotically inducible lipoprotein (osmE) | PA4876 | 49 | 1E-04 |

| Hypothetical membrane protein | PA5182 | 18 | 7E-04 |

| Probable permease of ABC transporter | PA3890 | 11 | 1E-04 |

| Hypothetical membrane protein | PA2777 | 11 | 7E-04 |

| Hypothetical membrane protein | PA3041 | 6 | 1E-04 |

| Hypothetical membrane protein | PA2148 | 4 | 1E-04 |

| Type III export protein pscE | PA1718 | −4 | 1E-03 |

| Probable lipoprotein localization protein (olB) | PA4668 | −4 | 1E-03 |

| Transcription/translation | |||

| Possible protease (pfpI) | PA0355 | 33 | 1E-03 |

| tRNA (guanine-N1)-methyltransferase (trmD) | PA3743 | −4 | 3E-05 |

| 16S rRNA processing protein (rimM) | PA3744 | −4 | 1E-03 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S8 (rpsH) | PA4249 | −4 | 5E-04 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L15 (rplO) | PA4244 | −4 | 1E-03 |

| Polyribonucleotide nucleotidyltransferase (pnp) | PA4740 | −4 | 4E-04 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L23 (rplW) | PA4261 | −7 | 1E-03 |

| Elongation factor G (fusAI) | PA4266 | −10 (−30) | 3E-04 |

| Metabolism | |||

| UDP-glucose 4-epimerase (galE) | PA1384 | 7 | 2E-04 |

| Probable c-type cytochrome (nirN) | PA0509 | 6 | 2E-05 |

| Probable glutamine amidotransferase | PA3459 | 5 | 2E-04 |

| Maleylacetoacetate isomerase | PA2007 | 5 | 5E-05 |

| Heme d1 biosynthesis protein (nirJ) | PA0511 | 5 | 1E-03 |

| Branched-chain alpha-keto acid dehydrogenase (bkdB) | PA2249 | 5 | 1E-03 |

| Homocysteine synthase (metY) | PA5025 | −4 | 1E-03 |

| Aspartate carbamoyltransferase (pyrB) | PA0402 | −5 | 4E-05 |

| Phosphoribosylamine-glycine ligase (purD) | PA4855 | −4 | 8E-04 |

| Transcriptional regulation | |||

| Transcriptional regulator (pyrR) | PA0403 | −4 | 1E-03 |

| Chemotaxis | |||

| Probable chemotaxis transducer | PA2573 | 4 | 3E-04 |

| Probable chemotaxis transducer | PA2867 | −5 | 2E-04 |

The following strains were compared: mucoid strain PAO578II (mucA22 sup-2 algU+) and its nonmucoid derivative, PAO6865 (algU::Tcr).

Numbers in parentheses show results of RT-PCR analyses of the corresponding genes as described in Materials and Methods. The displayed fold induction levels are calculated as 2ΔCT, where ΔCT represents the difference in CT of the two samples being compared, with CT representing the PCR cycle that crosses the preset logarithmic phase threshold.

Primer extension analysis.

Reverse transcription mapping was carried out as described previously (20). Primers were end labeled by polynucleotide kinase with [γ-32P]ATP (Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences, Boston, Mass.) for 1 h at 37°C. The reaction was stopped with 0.5 M EDTA, diluted with Tris-EDTA (TE), and heat inactivated by incubation at 65°C for 5 min. Labeled primers were annealed to 15 (CsCl isolation) or 3 (TRIzol isolation) μg of total cellular RNA in hybridization buffer (0.5 M KCl, O.24 M Tris-HCl [pH 8.3]) by dissociation at 95°C for 1 min followed immediately by annealing at 55°C for 2 min and stabilization on ice for 15 min. Primers were extended with Superscript II (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer's instructions and loaded adjacently to a sequencing ladder that utilized the same primer (33).

TaqMan real-time PCR.

P. aeruginosa mucoid strain PAO578II and its nonmucoid (algU::Tcr) derivative strain, PAO6865, were grown as described above. RNA was isolated with RNeasy (Qiagen), treated with RQ1 DNase (Promega) for 1 h at 37°C, and repurified with RNeasy. cDNA was synthesized as previously described. As a control, the reaction was also carried out without reverse transcriptase. Total cDNA was quantitated by spectrophotometry, and exactly 50 ng was used for reverse transcription (RT)-PCR.

RT-PCR was carried out on an ABI Prism 5700 with 500 nM PCR primers and 200 nM probe on 50 ng of isolated cDNA in triplicate. Additionally, RT-PCR of an equivalent volume of the cDNA synthesis reaction mixture that contained no reverse transcriptase indicated there was no contaminating genomic DNA, and a no-template control reaction indicated there was no cross-contamination. Primers and probes were designed for osmC and fusA1 by using Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). The PCR primers (Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc., Coralville, Iowa) for osmC were CAACCCCTATGGCTTCAATACC and TCAGCTCTTCCGGGTTGGT, and those for fusA1 were GGCCCGTACTACACCCATCA and CGTCAACGTGGGCACAGATA. The TaqMan probes (Applied Biosystems) were 6-FAM-CGAGGGCGCACC-TAMRA for osmC and 6-FAM-CGCTACCGTAATATC-TAMRA for fusA1.

RESULTS

Comparative global analysis of gene expression profiles in mucoid and nonmucoid P. aeruginosa.

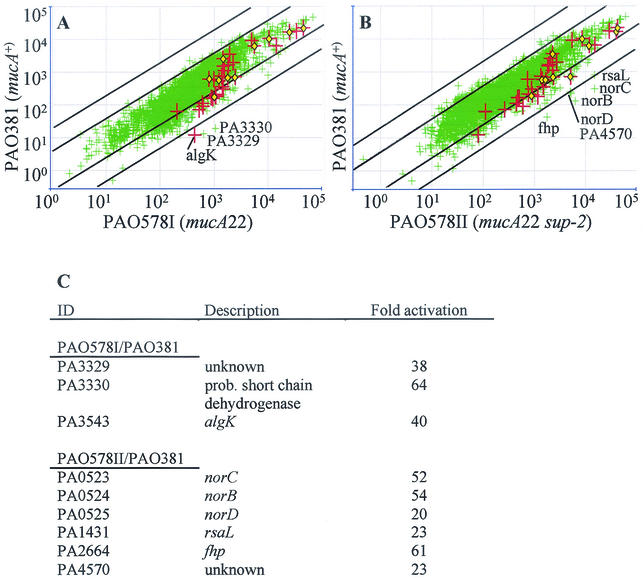

We investigated global gene expression in mucoid P. aeruginosa by using the recently available P. aeruginosa microarray gene chip. A comparison was carried out (Fig. 1A) between the wild-type nonmucoid strain PAO381 and its isogenic mucA22 mucoid mutant, PAO578I, which constitutively produces alginate. The mucA22 mutation truncates the anti-sigma factor MucA and renders AlgU fully active by relieving AlgU from inhibition by MucA (10, 43, 51). The transcripts of genes related to the regulation or production of alginate (Fig. 1A and Table 1) were shifted towards increased expression in the mucoid strain, with an observed induction of between twofold and ninefold for the majority of the genes. The algK gene, encoding a periplasmic lipoprotein implicated in the polymerization of alginate (32), showed an exceptionally high, 40-fold induction in the mucoid strain PAO578I versus its nonmucoid parent, PAO381. This appears to be due to uncharacteristically low background levels in PAO381 for the algK oligonucleotide set tiled on the microarray chip (data not shown), rather than being based on a dramatically elevated expression of algK in mucoid PAO578I relative to other alginate genes.

FIG. 1.

Global gene expression analysis in mucoid P. aeruginosa by transcriptional profiling with GeneChip microarrays. Each plot represents the merged expression data from three independent cultures run on three separate chips for each strain. Diagonal lines delimit regions with ≥4-fold or ≥20-fold induction. Large red crosses indicate alginate biosynthetic and regulatory genes (Table 1), and yellow diamonds indicate genes previously demonstrated to have AlgU-dependent promoters (Table 3). (A) Wild-type nonmucoid strain PAO381 (mucA+) compared to its isogenic mucoid mutant, PAO578I, carrying a typical mucA mutation (mucA22). (B) Nonmucoid strain PAO381 compared to the mucoid derivative, PAO578II (PAO578I sup-2), carrying both the mucA22 mutation responsible for conversion to mucoidy and the sup-2 mutation (55), which causes a slight attenuation of the mucoid phenotype often observed with CF isolates. (C) Identification (ID) and induction levels of genes designated on the figure The algK gene codes for periplasmic alginate secretion protein, norCBD codes for NO reductase, rsaL codes for the repressor of autoinducer synthase, and fhp codes for flavohemoglobin.

TABLE 1.

Microarray expression analysis of mucoid versus nonmucoid P. aeruginosa genes or operons related to alginate productiona

| Description (gene) | Identification | PAO578I/PAO381b

|

PAO578II/PAO6865c

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fold activation | P value | Fold activation | P value | ||

| Sigma factor (algU) | PA0762 | 2.0 | 9.0E-02 | 49.2 | 2E-03** |

| Anti-sigma factor (mucA) | PA0763 | 2.4 | 4.1E-02* | 20.8 | 3E-04** |

| Negative regulator of alginate biosynthesis (mucB) | PA0764 | 1.2 | 3.3E-01 | 7.0 | 1E-03** |

| Negative regulator of alginate biosynthesis (mucC) | PA0765 | 1.1 | 5.3E-01 | 4.1 | 6E-03** |

| Serine protease (mucD) | PA0766 | 1.1 | 5.1E-01 | 2.2 | 1E-03** |

| GDP-mannose 6-dehydrogenase (algD) | PA3540 | 4.0 | 7E-03** | 7.0 | 2.4E-02* |

| Alginate biosynthesis protein (alg8) | PA3541 | 4.0 | 2E-03** | 2.9 | 2.8E-01 |

| Alginate biosynthesis protein (alg44) | PA3542 | 5.0 | 6E-03** | 3.4 | 1.0E-02* |

| Alginate biosynthetic protein (algK) | PA3543 | 40.2 | 8E-03** | 5.8 | 5.1E-02* |

| Outer membrane protein (algE) | PA3544 | 5.0 | 5.3E-02* | 3.2 | 7.3E-02 |

| Alginate-c5-mannuronan-epimerase (algG) | PA3545 | 8.7 | 8E-03** | 3.5 | 7.7E-02 |

| Alginate biosynthesis protein (algX) | PA3546 | 5.2 | 1.9E-02* | 4.1 | 5.0E-02* |

| Poly (β-d-mannuronate) lyase (algL) | PA3547 | 8.5 | 3E-03** | 6.3 | 1.3E-01 |

| Alginate o-acetyltransferase (algI) | PA3548 | 7.5 | 9E-03** | 4.1 | 3.8E-02* |

| Alginate o-acetyltransferase (algJ) | PA3549 | 7.7 | 1E-03** | 7.6 | 1.2E-02* |

| Alginate o-acetyltransferase (algF) | PA3550 | 6.6 | 7.0E-02 | 16.0 | 3.9E-02* |

| Phosphomannose isomerase (algA) | PA3551 | 4.4 | 4E-03** | 4.3 | 6.0E-02 |

| Alginate regulatory protein (algP) | PA5253 | −1.8 | 2E-03** | −1.2 | 3.4E-01 |

| Alginate regulatory protein (algQ) | PA5255 | −1.7 | 6.1E-02 | −1.4 | 1.3E-01 |

| Alginate two-component regulatory protein (algR) | PA5261 | 1.4 | 3.5E-01 | 3.1 | 7.8E-02 |

| Alginate two-component regulatory protein (algZ) | PA5262 | 1.8 | 9E-03** | 2.2 | 2E-03** |

Values represent higher (positive) or lower (negative) expression in the mucoid strain than in the nonmucoid strain. *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01.

Mucoid strain PAO578I (mucA22) and its nonmucoid wild-type parental strain, PAO381 (mucA+).

Mucoid strain PAO578II (mucA22 sup-2 algU+) and its nonmucoid algU mutant derivative, PAO6865 (algU::Tcr).

A number of genes not implicated in alginate production were significantly induced in mucoid P. aeruginosa (Table 2) and often exceeded the fold induction values observed with the alginate-specific genes. The finding that the alginate biosynthetic genes are not the most highly induced genes (compare Tables 1 and 2), supports our hypothesis that a large number of additional genes are activated either directly or indirectly upon conversion to mucoidy via mucA mutations. Thus, the role of AlgU and the effects of its activation extend further than the control of alginate production.

We also observed only a small induction in the transcripts of the extracellular sigma factor (ECF) AlgU and the cotranscribed negative regulator MucA in the mucoid strain PAO578I compared to that in its wild-type parent, PAO381 (Table 1). AlgU positively regulates its own promoter, most likely contributing to the small induction observed (Table 1). Because algU is also transcribed from a number of AlgU-independent promoters (56), multiple transcripts initiated by different RNA polymerase holoenzymes may mask a contribution of AlgU when analyzed by microarrays. Furthermore, since the majority of the regulation of AlgU occurs at the posttranslational level by MucA (51), a large induction of AlgU transcription may not be a prerequisite to observe dramatic effects on alginate production. The putative alginate regulatory genes algP and algQ did not show induction in mucoid P. aeruginosa, and if anything, algP showed slightly reduced transcription. The algP gene encodes a P. aeruginosa histone-like element (37). The algQ gene was previously thought to encode a kinase phosphorylating the response regulator AlgR (52), but later was shown to be the ortholog of an anti-sigma factor affecting the major sigma factor RpoD (σ70) (19, 34). The out-of-sync transcription of algP and algQ relative to the rest of the alg genes suggests a rather indirect participation, if any, of these factors.

Global analysis of AlgU-dependent expression profiles in mucoid P. aeruginosa.

We next tested how inactivation of AlgU in mucoid (mucA mutant) P. aeruginosa affected global gene expression. For this purpose, a derivative of PAO578I, PAO578II (PAO578I sup-2), which has an additional sup-2 mutation that renders it responsive to growth conditions for maximal production of alginate, was employed (55). This strain, unlike PAO578I, in which algU inactivation cannot be achieved, permits inactivation of algU. The strain PAO6865 is an algU::Tcr derivative of PAO578II (9). When the microarray expression data (Fig. 1B) from PAO578II and PAO6865 were compared, genes with a previously demonstrated AlgU-dependent promoter (20) (Fig. 1B and Table 3) showed a wide range of expression ratios. The highest levels of differential AlgU-dependent expression were observed with the following genes: (i) slyB (ycfJ), encoding a putative porin (41); (ii) lptA, encoding a lipoprotein capable of inducing IL-8 production by human monocytes (20); (iii) osmC and osmE, inducible by elevated osmolarity and potentially playing a role in stress defense (13, 27, 28) (with OsmE also being a lipoprotein thus having a proinflammatory potential); and (iv) pfpI, encoding a homolog (64% similar) of the major protease from Pyrococcus furiosus (29). In some cases, such as with the algU-mucABCD gene cluster, a gradient of induction could be detected along the putative operon (Table 1) consistent with a transcription gradient or mRNA degradation from the 3′ end of an operonic transcript. The alginate biosynthetic cluster, extending from algD to algA, showed a relatively uniform induction, algD yielding the strongest AlgU-dependent signal in the cluster, with the exception of algF and algJ.

Induction of virulence determinants associated with conversion to mucoidy in P. aeruginosa.

In addition to alginate production, several factors that may play a role in P. aeruginosa pathogenesis are induced (fold induction of ≥4, P ≤ 0.001) upon conversion to mucoidy (Table 2). (i) lasB, the gene that encodes the virulence factor elastase (5), was induced in mucoid P. aeruginosa, consistent with an association previously described in the sputum of CF patients (59). (ii) Also consistent with the previously reported in vivo data (59) was a smaller induction of lasA (not included in Table 2; induction of 3.3-fold, P = 0.004), encoding a protease that is able to degrade host elastin and collagen (61). (iii) A weak induction, if any, of exotoxin A (toxA gene [not shown in Table 2]) was also observed (1.7-fold, P = 0.01). (iv) The aprA gene, encoding the alkaline metalloproteinase implicated in obtaining iron at the site of infection through the degradation of transferrin (57), and genes for its secretion, aprE and aprF, were among the most highly induced genes. Since alkaline protease is activated by elastase (LasB) (46) and is important for the activation of the LasA protease (65), it appears that conversion to mucoidy simultaneously induces genes for production of the major proteases and proteolytic activation cascades in P. aeruginosa. (v) The plcR gene is important for the function of the hemolytic phospholipase C (PlcH), and when knocked out results in 10-times-less hemolytic activity by phospholipase C (14). Thus, conversion to mucoidy may play a role in facilitating phospholipase action.

Additionally, genes producing secreted factors that may be intoxicating to the host were coinduced with conversion to mucoidy (Table 2). The enzymes encoded by the hcnABC cluster, hcnA (sixfold induction, P = 2E-04), hcnC (sixfold induction, P = 1E-03 [shown in Table 1]), and hcnB (fourfold induction, P = 3E-03) generate the secreted, extremely toxic secondary metabolite hydrogen cyanide (HCN). HCN has been shown to contribute to the pathogenesis of P. aeruginosa (24). Cyanide production inhibits cytochrome c oxidase, resulting in a block in the terminal component in mitochondrial respiration (6). There was also an induction of genes encoding putative nonribosomal peptide synthetases in mucoid P. aeruginosa (Table 2). These types of enzymes utilize unconventional amino acids and modifications to generate short peptides with a variety of biological activities, including disabling defense systems in the host, such as the immunosuppressant cyclosporine (53).

Activation of defense mechanisms in mucoid P. aeruginosa with attenuated alginate expression due to a sup-2 suppressor mutation.

Many mucoid P. aeruginosa CF isolates typically resemble the PAO578II strain in terms of their somewhat attenuated alginate production, attributed to a suppressor mutation termed “sup-2” (18, 55). Since it is typical to coisolate type I (with constitutive alginate expression as in PAO578I) and type II (as in PAO578II, which requires additional specific environmental conditions to display a mucoid phenotype) strains of mucoid P. aeruginosa from CF lungs, we also used microarray analysis to compare PAO578II (PAO381 mucA22 sup-2) with the parental strain, PAO381 (mucA+ sup-20) (Fig. 1B and C).

Among the most highly induced genes in the comparison of PAO578II with PAO381 (Fig. 1) were norB and norC, encoding the b and c subunits, respectively, of the P. aeruginosa nitric oxide (NO) reductase (2), which could play a role in bacterial defense against host innate immune clearance mechanisms, such as reactive nitrogen intermediates (31). Another member of this operon, norD, the activity of which is required for NO reductase activity, also showed elevated transcription (15). Also potentially important in NO detoxification is the induced fhp gene encoding a P. aeruginosa flavohemoglobin homolog. Fhp has been shown in other organisms to detoxify NO under aerobic conditions (25).

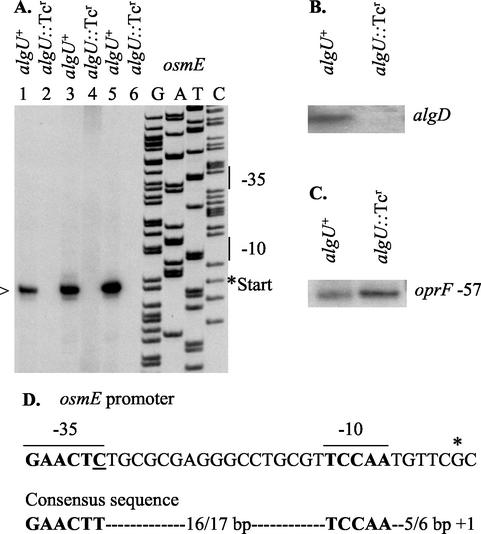

Confirmation of the predicted osmE AlgU (σE)-dependent promoter by RT mapping.

The osmE gene showed one of the highest AlgU-dependent activation levels in mucoid P. aeruginosa (49-fold; Table 3) and was chosen for further potential AlgU promoter sequence investigations. A candidate promoter, not previously recognized by a bioinformatics approach using a stringent AlgU (P. aeruginosa σE) promoter consensus sequence (20), was found 37 bp upstream of the lipoprotein osmE translational start site. The putative osmE promoter sequence showed one T→C substitution (underlined) in the −35 consensus region (GAACTC) and a perfect −10 P. aeruginosa consensus region (TCCAA) (Fig. 2D). We next mapped the osmE mRNA 5′ end (Fig. 2A) by primer extension (RT) analysis. When run adjacently to a sequencing ladder, an osmE transcript was observed initiating 6 bp downstream of the predicted AlgU −10 consensus sequence (Fig. 2A). The transcript was present in the mucoid strain PAO578II (AlgU+ mucA22) with a functional AlgU sigma factor, but the corresponding band was absent in the algU-knockout strain PAO6865 (algU::Tcr mucA22) derived from PAO578II. These data show osmE promoter dependence on AlgU. Furthermore, the mRNA 5′ end was positioned correctly relative to the predicted AlgU (σE) −35 and −10 promoter regions. As a control, the promoter of algD was included, and as expected, it showed AlgU dependence (Fig. 2B). An AlgU-independent promoter 57 bp upstream of oprF was also included as an RNA quality and loading control (Fig. 2C). The mapping of the osmE promoter validated the microarray results for the osmE gene. In addition to mapping the osmE promoter and showing its dependence on AlgU, we also validated the microarray data by examining two genes at opposite ends of the expression spectrum (osmC and fusA1; Table 3) using real-time PCR. The results showed for osmC a 91-fold increase and for fusA1 a 30-fold reduction in algU+ cells relative to algU mutant cells. This is in keeping with the 24-fold increase in osmC expression and 10-fold decrease in fusA1 levels by microarrays.

FIG. 2.

Mapping of the AlgU-dependent osmE promoter. (A) Primer extension mapping of the osmE mRNA 5′ end corresponding to the AlgU consensus promoter. Total RNA was isolated from the mucoid strain PAO578II (mucA22 sup-2) (lanes 1, 3, and 5) or its algU knockout nonmucoid derivative, PAO6865 (PAO578II algU::Tcr) (lanes 2, 4, and 6). Lanes 1 and 2 contain 3 μg of RNA from a batch used in microarray analysis, and lanes 3 to 6 contain 15 μg of RNA obtained by a CsCl isolation procedure (20). Primer extension products were run adjacently to a sequencing ladder generated with the same primer. Bars denote the AlgU promoter consensus sequence. >, AlgU-dependent mRNA start site. (B) A previously identified AlgU-dependent promoter, algD, used as a positive control for AlgU-dependent transcription. (C) A promoter 57 bp upstream of the oprF gene, which is independent of AlgU, used to demonstrate equivalent loading of RNA (a negative control for AlgU-dependent transcription). (D) The osmE AlgU-dependent promoter sequence with the −35 and −10 regions indicated by boldface letters. A T→C substitution relative to the strict AlgU consensus −35 region is underlined. (Note that this is the first AlgU [σE] promoter with a variant nucleotide in this position.) An asterisk marks the transcriptional start site.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we utilized microarrays to probe global gene expression associated with conversion to mucoidy in P. aeruginosa. The observed increased expression in mucoid strains of a number of previously described AlgU-dependent promoters (20) validated our microarray analysis. In conjunction with bioinformatics tools, a new AlgU-dependent promoter has been identified upstream of the highly induced osmE gene, encoding an osmotically responsive lipoprotein, OsmE, underscoring the validity of the microarray findings. Our data show that AlgU is a global stress response sigma factor that induces a number of systems in P. aeruginosa, not only the alginate system. Furthermore, we report the identity of gene subsets encoding virulence factors specifically induced with conversion to mucoidy, which include proteases and toxic products such as HCN.

Genes with previously demonstrated AlgU-dependent promoters (20) show a wide range of induction levels (Table 3). The slyB, lptA, osmC, and algD genes represent a category that has a strong if not complete dependence on AlgU for induction. Other genes that have an AlgU-dependent promoter, but which do not show a strong induction in mucoid strains (asmD3, asmD2, asmB2, rpoH, oprF, and lptB) may also be under the control of additional regulators or promoters, such as in the case of oprF, encoding the major outer membrane protein porin F of P. aeruginosa. The oprF gene has two additional promoters, one of which is dependent on SigX (11), and thus the contributions of AlgU may be masked. The lptB gene was previously shown to have two overlapping promoters—one dependent on AlgU and a second one independent of AlgU, which compensates for the absence of AlgU-dependent transcripts in the AlgU mutant strain PAO6865 through its increased activity (20).

Transcription profiles in the CF-specific, mucoid phenotype suggest that conversion to mucoidy may have specific deleterious effects in the CF patient, in addition to the known roles of mucoidy in antiphagocytosis (38, 47), hypochlorite and reactive oxygen intermediate scavenging (39, 58), and specialized, aggressive biofilm formation distinct from that of environmental biofilms (30). Regarding the issues associated with biofilm formation, it is not clear at this point whether the biofilms studied by using nonmucoid P. aeruginosa grown on environmental substrates have a direct relationship (if any) to mucoid P. aeruginosa in CF. A comparison of our microarray data with those reported for P. aeruginosa isolates grown on granite rock (Table 4) shows little correlation, if any, in gene expression trends. This comparison does not take into account the significant differences in experimental designs, and potential overlaps cannot be ruled out at this point.

TABLE 4.

Comparison of mucoid P. aeruginosa and reported environmental biofilm gene expression

| Description (gene) | Identification | Biofilma,b fold activation | Mucoid/nonmucoidc

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fold activation | P value | |||

| Bacteriophage genes | ||||

| Hypothetical protein of bacteriophage Pf1 | PA0718 | 22.6 | 1.6 | 2E-01 |

| Helix-destabilizing protein of bacteriophage Pf1 | PA0720 | 35.2 | 1.4 | 9E-02 |

| Hypothetical protein of bacteriophage Pf1 | PA0721 | 26.6 | 1.4 | 6E-01 |

| Hypothetical protein of bacteriophage Pf1 | PA0722 | 64.2 | −1.0 | 9E-01 |

| Coat protein B of bacteriophage Pf1 (coaB) | PA0723 | 83.5 | −1.5 | 2E-01 |

| Probable coat protein A of bacteriophage Pf1 | PA0724 | 10.1 | 1.7 | 6E-02 |

| Hypothetical protein of bacteriophage Pf1 | PA0725 | 9.9 | 1.4 | 7E-02 |

| Hypothetical protein of bacteriophage Pf1 | PA0726 | 8.9* | 2.3 | 4E-02 |

| Hypothetical protein from bacteriophage Pf1 | PA0727 | 14.6 | 1.6 | 9E-02 |

| Motility and attachment | ||||

| Probable fimbrial protein | PA2128 | −16.5* | −4.0 | 3E-02 |

| Probable pilus assembly chaperone | PA2129 | −2.4 | 1.2 | 6E-01 |

| Type 4 fimbrial precursor PilA | PA4525 | −6.6* | −2.5 | 2E-02 |

| Flagellar hook protein FlgE | PA1080 | −2* | −1.7 | 3E-02 |

| Flagellin type B, FliC | PA1092 | −2.3* | −2.9 | 1E-02 |

| Flagellar capping protein FliD | PA1094 | −2.1* | −1.9 | 7E-03 |

| Probable pilus assembly chaperone | PA2129 | −2.4 | 1.2 | 6E-01 |

| Translation | ||||

| 50S ribosomal protein L28 (rpmB) | PA5316 | 4.4 | −2.4 | 1E-01 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L19 (rplS) | PA3742 | 2.7 | −3.0 | 9E-02 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L23 (rplW) | PA4261 | 2.3 | −2.6 | 6E-03 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L4 | PA4262 | 2.4 | −2.3 | 5E-02 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S7 (rpsG) | PA4267 | 2.2 | −1.5 | 2E-02 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L18 (rplR) | PA4247 | 2.3 | −1.9 | 7E-03 |

| Translation initiation factor IF-2 (infB) | PA4744 | 2.1 | −1.4 | 1E-02 |

| Ribosome modulation factor (rmf) | PA3049 | −5.3 | −1.3 | 3E-01 |

| ATP-binding protease component ClpA | PA2620 | −2.1* | −1.3 | 2E-02 |

| Metabolism | ||||

| Cytochrome c oxidase, subunit II (coxB) | PA0105 | −2.9 | 1.7 | 1E-03 |

| Cytochrome c oxidase, subunit I (coxA) | PA0106 | −2.7 | 2.0 | 1E-01 |

| Cytochrome c oxidase, subunit III (coIII) | PA0108 | −2.9 | 2.4 | 1E-03 |

| Urease beta subunit (ureB) | PA4867 | 63.1 | −1.2 | 2E-01 |

| Lipoate-protein ligase B (lipB) | PA3997 | 2.8 | −1.1 | 6E-01 |

| Leucine dehydrogenase (glpD) | PA3584 | −4.1 | 1.1 | 7E-01 |

| Leucine dehydrogenase (ldh) | PA3418 | −2.5 | 1.0 | 8E-01 |

| Membrane proteins or secretion | ||||

| TolA protein (tolA) | PA0971 | 3.9* | 3.1 | 2E-02 |

| Translocation protein TatA | PA5068 | 2.4 | 1.3 | 1E-01 |

| Translocation protein TatB | PA5069 | 6.9 | 1.8 | 6E-02 |

| Outer membrane lipoprotein OmlA | PA4765 | 2.4 | −1.7 | 2E-03 |

| Probable porin | PA3038 | −3.5 | −1.2 | 6E-01 |

| Exoenzyme S synthesis protein C (exsC) | PA1710 | −2.5* | −3.0 | 3E-02 |

| Probable sodium-solute symporter | PA3234 | −2.3 | 1.2 | 3E-01 |

| Regulation | ||||

| Probable transcriptional regulator | PA2547 | 3.1 | 1.5 | 2E-01 |

| Sigma factor RpoH | PA0376 | 2.3 | 1.1 | 6E-01 |

| Sigma factor RpoS | PA3622 | −2.3 | 1.1 | 4E-01 |

| Probable two-component response regulator | PA4296 | −2.2 | 1.0 | 9E-01 |

| Other | ||||

| Rod shape-determining protein MreC | PA4480 | 3.1 | 1.2 | 9E-02 |

| Probable DNA-binding protein | PA5348 | −4.6* | −1.5 | 1E-02 |

| Probable glycosyl hydrolase | PA2160 | −2.3 | 2.1 | 3E-02 |

| Methylated DNA-protein-cysteine methyltransferase (ogt) | PA0995 | −2.1 | −1.5 | 2E-01 |

Environmental biofilm data as presented in Table 1 of the article by Whiteley et al. (63), reporting differential gene expression in P. aeruginosa PAO1 grown as biofilm relative to planktonic growth.

Asterisks indicate correlation of gene expression trends in mucoid and biofilm phenotypes.

Mucoid PAO578I and nonmucoid PAO381. The genes included are those reported by Whiteley et al. (63) to display differential expression in the biofilm mode of growth.

In our studies, induction of genes encoding several potent virulence factors (elastase, LasA protease, alkaline proteinase, and PlcR) and dangerous toxic products (HCN) was observed. Although the microarray analysis of mucoid P. aeruginosa showed a general induction of the alginate biosynthetic pathway, somewhat surprisingly, the alginate genes (with the notable exception of algK) did not receive the highest scores. We also did not observe induction of some of the putative regulators of alginate production, algP and algQ. However, even the well-documented regulators of alginate production, the algU-mucABCD cluster and algZR did not show signs of a high expression differential between mucoid strain PAO578I and its nonmucoid parental strain, PAO381.

Because alginate production is energetically taxing to the bacterium, there may exist a selective pressure in P. aeruginosa strains carrying mucA mutations to down-regulate this system. Good evidence for the existence of such pressure is the accumulation of second site suppressor mutations, such as sup-2, both in laboratory strains and in CF isolates (49, 55). This burden is further demonstrated by the highly unstable mucoid phenotype (18, 55). Intriguingly, the suppressor mutations not only down-regulate alginate production to metabolically sustainable levels, but simultaneously activate additional defense systems (norB, norC, and fhp) (Fig. 1B and C) that may protect the bacteria from NO and the downstream highly bactericidal combinatorial products of NO and reactive oxygen intermediates. Incidentally, alginate itself is a scavenger of reactive oxygen intermediates, and it seems that by slight attenuation of its production to energetically more favorable levels via sup-2 mutations, P. aeruginosa isolates from CF simultaneously gain resistance to another source of bactericidal radicals, viz. NO and reactive nitrogen intermediates.

Additional products coinduced with the conversion to a mucoid phenotype are known virulence traits of P. aeruginosa. Secretion of a freely diffusible toxic secondary metabolite, HCN, by P. aeruginosa is known to inhibit cytochrome c oxidase of the mitochondria (64). Recently, HCN has been demonstrated to be a potent P. aeruginosa virulence factor according to a Caenorhabditis elegans infection model (24). HCN has also been implicated in the inhibition of several other metalloenzymes, such as catalase, peroxidase, superoxide dismutase, nitrate reductase, and nitrogenase (6), and as a result may play an important role in bacterial defense against reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates produced by the host.

Previously, Storey et al. found a correlation between algD transcripts and lasB transcripts in the sputa of CF patients (59). They also noted a weaker but significant correlation of algD with lasA transcripts. These findings closely mirror the results we obtained with microarray analysis of mucoid P. aeruginosa strains carrying mucA but not sup-2 mutations. The lasB gene was strongly induced in mucoid P. aeruginosa, as was lasA, albeit to a lesser extent. The correlation of transcripts observed by microarray analysis in this study with those observed in vivo suggests that at least some aspects of the microarray analysis of mucoid P. aeruginosa in vitro may accurately reflect the situation in the CF lung.

Consistent with the role of AlgU as the founding member (42, 44) of the extracytoplasmic function (ECF) class of sigma factors (45, 50), we found a number of AlgU-inducible genes, encoding products predicted to be associated with membranes (Tables 2 and 3). While at least some of these genes may be involved in the production of alginate, others seem to be involved in bacterial adhesion (Table 2). Our data also indicate a potential link between conversion to mucoidy and drug resistance mechanisms, such as through drug efflux (e.g., PA3521 is induced sevenfold in the mucoid strain) (Table 2). Identification via microarray analysis of P. aeruginosa membrane proteins associated with the medically relevant mucoid phenotype may offer new vaccine candidates to prevent or combat chronic P. aeruginosa infections. The action of proteases or metabolic enzymes induced in mucoid P. aeruginosa could also be considered as future drug targets for intervention with critical bacterial activities coinduced with mucoidy during colonization in CF. The studies presented here define additional genes associated with conversion to a mucoid phenotype in P. aeruginosa that will be of importance to fully understand pathology in the CF host.

Acknowledgments

We thank Michal H. Mudd for technical expertise and help with this study and Lisa Tatterson and Jens Poschet for discussions. Microarray equipment and technical support were supplied by the Keck-UNM Genomics Resource core facility at the University of New Mexico.

The cost of P. aeruginosa microarray chips was defrayed in part by subsidy grant no. 012 from Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Therapeutics, Inc. This work was supported by NIH grant AI31139.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aliprantis, A. O., R. B. Yang, M. R. Mark, S. Suggett, B. Devaux, J. D. Radolf, G. R. Klimpel, P. Godowski, and A. Zychlinsky. 1999. Cell activation and apoptosis by bacterial lipoproteins through toll-like receptor-2. Science 285:736-739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arai, H., Y. Igarashi, and T. Kodama. 1995. The structural genes for nitric oxide reductase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1261:279-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arfin, S. M., A. D. Long, E. T. Ito, L. Tolleri, M. M. Riehle, E. S. Paegle, and G. W. Hatfield. 2000. Global gene expression profiling in Escherichia coli K12. The effects of integration host factor. J. Biol. Chem. 275:29672-29684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baldi, P., and A. D. Long. 2001. A Bayesian framework for the analysis of microarray expression data: regularized t-test and statistical inferences of gene changes. Bioinformatics 17:509-519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bever, R. A., and B. H. Iglewski. 1988. Molecular characterization and nucleotide sequence of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa elastase structural gene. J. Bacteriol. 170:4309-4314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blumer, C., and D. Haas. 2000. Mechanism, regulation, and ecological role of bacterial cyanide biosynthesis. Arch. Microbiol. 173:170-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonfield, T. L., J. R. Panuska, M. W. Konstan, K. A. Hillard, J. B. Hillard, H. Ghnaim, and M. Berger. 1995. Inflammatory cytokines in cystic fibrosis lungs. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 152:2111-2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boucher, J. C., J. Martinez-Salazar, M. J. Schurr, M. H. Mudd, H. Yu, and V. Deretic. 1996. Two distinct loci affecting conversion to mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis encode homologs of the serine protease HtrA. J. Bacteriol. 178:511-523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boucher, J. C., M. J. Schurr, and V. Deretic. 2000. Dual regulation of mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and sigma factor antagonism. Mol. Microbiol. 36:341-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boucher, J. C., H. Yu, M. H. Mudd, and V. Deretic. 1997. Mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis: characterization of muc mutations in clinical isolates and analysis of clearance in a mouse model of respiratory infection. Infect. Immun. 65:3838-3846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brinkman, F. S. L., G. Schoofs, R. E. W. Hancock, and R. De Mot. 1999. Influence of a putative ECF sigma factor on expression of the major outer membrane protein, OprF, in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Pseudomonas fluorescens. J. Bacteriol. 181:4746-4754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burns, J. L., R. L. Gibson, S. McNamara, D. Yim, J. Emerson, M. Rosenfeld, P. Hiatt, K. McCoy, R. Castile, A. L. Smith, and B. W. Ramsey. 2001. Longitudinal assessment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in young children with cystic fibrosis. J. Infect. Dis. 183:444-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conter, A., C. Gangneux, M. Suzanne, and C. Gutierrez. 2001. Survival of Escherichia coli during long-term starvation: effects of aeration, NaCl, and the rpoS and osmC gene products. Res. Microbiol. 152:17-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cota-Gomez, A., A. I. Vasil, J. Kadurugamuwa, T. J. Beveridge, H. P. Schweizer, and M. L. Vasil. 1997. PlcR1 and PlcR2 are putative calcium-binding proteins required for secretion of the hemolytic phospholipase C of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect. Immun. 65:2904-2913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Boer, A. P., J. van der Oost, W. N. Reijnders, H. V. Westerhoff, A. H. Stouthamer, and R. J. van Spanning. 1996. Mutational analysis of the nor gene cluster which encodes nitric-oxide reductase from Paracoccus denitrificans. Eur. J. Biochem. 242:592-600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deretic, V., J. F. Gill, and A. M. Chakrabarty. 1987. Gene algD coding for GDPmannose dehydrogenase is transcriptionally activated in mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 169:351-358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deretic, V., J. F. Gill, and A. M. Chakrabarty. 1987. Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in cystic fibrosis: nucleotide sequence and transcriptional regulation of the algD gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 15:4567-4581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeVries, C. A., and D. E. Ohman. 1994. Mucoid-to-nonmucoid conversion in alginate-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa often results from spontaneous mutations in algT, encoding a putative alternate sigma factor, and shows evidence for autoregulation. J. Bacteriol. 176:6677-6687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dove, S. L., and A. Hochschild. 2001. Bacterial two-hybrid analysis of interactions between region 4 of the σ70 subunit of RNA polymerase and the transcriptional regulators Rsd from Escherichia coli and AlgQ from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 183:6413-6421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Firoved, A. M., J. C. Boucher, and V. Deretic. 2002. Global genomic analysis of AlgU (σE)-dependent promoters (sigmulon) in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and implications for inflammatory processes in cystic fibrosis. J. Bacteriol. 184:1057-1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.FitzSimmons, S. C. 1993. The changing epidemiology of cystic fibrosis. J. Pediatr. 122:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flynn, J. L., and D. E. Ohman. 1988. Cloning of genes from mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa which control spontaneous conversion to the alginate production phenotype. J. Bacteriol. 170:1452-1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fyfe, J. A., and J. R. Govan. 1980. Alginate synthesis in mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a chromosomal locus involved in control. J. Gen. Microbiol. 119:443-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gallagher, L. A., and C. Manoil. 2001. Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 kills Caenorhabditis elegans by cyanide poisoning. J. Bacteriol. 183:6207-6214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gardner, A. M., R. A. Helmick, and P. R. Gardner. 2002. Flavorubredoxin, an inducible catalyst for nitric oxide reduction and detoxification in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 277:8172-8177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Govan, J. R. W., and V. Deretic. 1996. Microbial pathogenesis in cystic fibrosis: mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia. Microbiol. Rev. 60:539-574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gutierrez, C., and J. C. Devedjian. 1991. Osmotic induction of gene osmC expression in Escherichia coli K12. J. Mol. Biol. 220:959-973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gutierrez, C., S. Gordia, and S. Bonnassie. 1995. Characterization of the osmotically inducible gene osmE of Escherichia coli K-12. Mol. Microbiol. 16:553-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Halio, S. B., I. I. Blumentals, S. A. Short, B. M. Merrill, and R. M. Kelly. 1996. Sequence, expression in Escherichia coli, and analysis of the gene encoding a novel intracellular protease (PfpI) from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. J. Bacteriol. 178:2605-2612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hentzer, M., G. M. Teitzel, G. J. Balzer, A. Heydorn, S. Molin, M. Givskov, and M. R. Parsek. 2001. Alginate overproduction affects Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm structure and function. J. Bacteriol. 183:5395-5401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Householder, T. C., E. M. Fozo, J. A. Cardinale, and V. L. Clark. 2000. Gonococcal nitric oxide reductase is encoded by a single gene, norB, which is required for anaerobic growth and is induced by nitric oxide. Infect. Immun. 68:5241-5246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jain, S., and D. E. Ohman. 1998. Deletion of algK in mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa blocks alginate polymer formation and results in uronic acid secretion. J. Bacteriol. 180:634-641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jensen, E. T., A. Kharazmi, K. Lam, J. W. Costerton, and N. Høiby. 1990. Human polymorphonuclear leukocyte response to Pseudomonas aeruginosa grown in biofilms. Infect. Immun. 58:2383-2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jishage, M., and A. Ishihama. 1998. A stationary phase protein in Escherichia coli with binding activity to the major sigma subunit of RNA polymerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:4953-4958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koch, C., and N. Hoiby. 1993. Pathogenesis of cystic fibrosis. Lancet 341:1065-1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Konstan, M. W., P. J. Byard, C. L. Hoppel, and P. B. Davis. 1995. Effect of high-dose ibuprofen in patients with cystic fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 332:848-854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Konyecsni, W. M., and V. Deretic. 1990. DNA sequence and expression analysis of algP and algQ, components of the multigene system transcriptionally regulating mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: algP contains multiple direct repeats. J. Bacteriol. 172:2511-2520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krieg, D. P., R. J. Helmke, V. F. German, and J. A. Mangos. 1988. Resistance of mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa to nonopsonic phagocytosis by alveolar macrophages in vitro. Infect. Immun. 56:3173-3179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Learn, D. B., E. P. Brestel, and S. Seetharama. 1987. Hypochlorite scavenging by Pseudomonas aeruginosa alginate. Infect. Immun. 55:1813-1818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Long, A. D., H. J. Mangalam, B. Y. Chan, L. Tolleri, G. W. Hatfield, and P. Baldi. 2001. Improved statistical inference from DNA microarray data using analysis of variance and a Bayesian statistical framework. Analysis of global gene expression in Escherichia coli K12. J. Biol. Chem. 276:19937-19944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ludwig, A., C. Tengel, S. Bauer, A. Bubert, R. Benz, H. J. Mollenkopf, and W. Goebel. 1995. SlyA, a regulatory protein from Salmonella typhimurium, induces a haemolytic and pore-forming protein in Escherichia coli. Mol. Gen. Genet. 249:474-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martin, D. W., B. W. Holloway, and V. Deretic. 1993. Characterization of a locus determining the mucoid status of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: AlgU shows sequence similarities with a Bacillus sigma factor. J. Bacteriol. 175:1153-1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martin, D. W., M. J. Schurr, M. H. Mudd, J. R. W. Govan, B. W. Holloway, and V. Deretic. 1993. Mechanism of conversion to mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa infecting cystic fibrosis patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:8377-8381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martin, D. W., M. J. Schurr, H. Yu, and V. Deretic. 1994. Analysis of promoters controlled by the putative sigma factor AlgU regulating conversion to mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: relationship to σE and stress response. J. Bacteriol. 176:6688-6696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Missiakas, D., and S. Raina. 1998. The extracytoplasmic function sigma factors: role and regulation. Mol. Microbiol. 28:1059-1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miyajima, S., T. Akaike, K. Matsumoto, T. Okamoto, J. Yoshitake, K. Hayashida, A. Negi, and H. Maeda. 2001. Matrix metalloproteinases induction by pseudomonal virulence factors and inflammatory cytokines in vitro. Microb. Pathog. 31:271-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oliver, A. M., and D. M. Weir. 1983. Inhibition of bacterial binding to mouse macrophages by Pseudomonas alginate. J. Clin. Lab. Immunol. 10:221-224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pedersen, S. S. 1992. Lung infection with alginate-producing, mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis. APMIS 100(Suppl. 28):1-79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pugashetti, B. K., H. M. Metzger, Jr., L. Vadas, and D. S. Feingold. 1982. Phenotypic differences among clinically isolated mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 16:686-691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Raivio, T. L., and T. J. Silhavy. 2001. Periplasmic stress and ECF sigma factors. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 55:591-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rowen, D. W., and V. Deretic. 2000. Membrane-to-cytosol redistribution of ECF sigma factor AlgU and conversion to mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from cystic fibrosis patients. Mol. Microbiol. 36:314-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roychoudhury, S., K. Sakai, and A. M. Chakrabarty. 1992. AlgR2 is an ATP/GTP-dependent protein kinase involved in alginate synthesis by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:2659-2663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ruhlmann, A., and A. Nordheim. 1997. Effects of the immunosuppressive drugs CsA and FK506 on intracellular signalling and gene regulation. Immunobiology 198:192-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schurr, M. J., and V. Deretic. 1997. Microbial pathogenesis in cystic fibrosis: co-ordinate regulation of heat-shock response and conversion to mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 24:411-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schurr, M. J., D. W. Martin, M. H. Mudd, and V. Deretic. 1994. Gene cluster controlling conversion to alginate-overproducing phenotype in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: functional analysis in a heterologous host and role in the instability of mucoidy. J. Bacteriol. 176:3375-3382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schurr, M. J., H. Yu, J. C. Boucher, N. S. Hibler, and V. Deretic. 1995. Multiple promoters and induction by heat shock of the gene encoding the alternative sigma factor AlgU (σE) which controls mucoidy in cystic fibrosis isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 177:5670-5679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shigematsu, T., J. Fukushima, M. Oyama, M. Tsuda, S. Kawamoto, and K. Okuda. 2001. Iron-mediated regulation of alkaline proteinase production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiol. Immunol. 45:579-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Simpson, J. A., S. E. Smith, and R. T. Dean. 1989. Scavenging by alginate of free radicals released by macrophages. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 6:347-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Storey, D. G., E. E. Ujack, I. Mitchell, and H. R. Rabin. 1997. Positive correlation of algD transcription to lasB and lasA transcription by populations of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the lungs of patients with cystic fibrosis. Infect. Immun. 65:4061-4067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stover, C. K., X. Q. Pham, A. L. Erwin, S. D. Mizoguchi, P. Warrener, M. J. Hickey, F. S. Brinkman, W. O. Hufnagle, D. J. Kowalik, M. Lagrou, R. L. Garber, L. Goltry, E. Tolentino, S. Westbrock-Wadman, Y. Yuan, L. L. Brody, S. N. Coulter, K. R. Folger, A. Kas, K. Larbig, R. Lim, K. Smith, D. Spencer, G. K. Wong, Z. Wu, and I. T. Paulsen. 2000. Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA01, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature 406:959-964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Toder, D. S., S. J. Ferrell, J. L. Nezezon, L. Rust, and B. H. Iglewski. 1994. lasA and lasB genes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: analysis of transcription and gene product activity. Infect. Immun. 62:1320-1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Welsh, M. J., L.-C. Tsui, T. F. Boat, and A. L. Beaudet. 1995. Cystic fibrosis, p. 3799-3876. In C. R. Scriver, A. L. Beaudet, W. S. Sly, and D. Valle (ed.), The metabolic and molecular basis of inherited disease, vol. III. McGraw-Hill, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 63.Whiteley, M., M. G. Bangera, R. E. Bumgarner, M. R. Parsek, G. M. Teitzel, S. Lory, and E. P. Greenberg. 2001. Gene expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Nature 413:860-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wilson, M. T., G. Antonini, F. Malatesta, P. Sarti, and M. Brunori. 1994. Probing the oxygen binding site of cytochrome c oxidase by cyanide. J. Biol. Chem. 269:24114-24119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wolz, C., E. Hellstern, M. Haug, D. R. Galloway, M. L. Vasil, and G. Doring. 1991. Pseudomonas aeruginosa LasB mutant constructed by insertional mutagenesis reveals elastolytic activity due to alkaline proteinase and the LasA fragment. Mol. Microbiol. 5:2125-2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yu, H., M. J. Schurr, and V. Deretic. 1995. Functional equivalence of Escherichia coli σE and Pseudomonas aeruginosa AlgU: E. coli rpoE restores mucoidy and reduces sensitivity to reactive oxygen intermediates in algU mutants of P. aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 177:3259-3268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]