Abstract

Burkholderia cenocepacia is an important opportunistic pathogen of patients with cystic fibrosis. This bacterium is inherently resistant to a wide range of antimicrobial agents, including high concentrations of antimicrobial peptides. We hypothesized that the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of B. cenocepacia is important for both virulence and resistance to antimicrobial peptides. We identified hldA and hldD genes in B. cenocepacia strain K56-2. These two genes encode enzymes involved in the modification of heptose sugars prior to their incorporation into the LPS core oligosaccharide. We constructed a mutant, SAL1, which was defective in expression of both hldA and hldD, and by performing complementation studies we confirmed that the functions encoded by both of these B. cenocepacia genes were needed for synthesis of a complete LPS core oligosaccharide. The LPS produced by SAL1 consisted of a short lipid A-core oligosaccharide and was devoid of O antigen. SAL1 was sensitive to the antimicrobial peptides polymyxin B, melittin, and human neutrophil peptide 1. In contrast, another B. cenocepacia mutant strain that produced complete lipid A-core oligosaccharide but lacked polymeric O antigen was not sensitive to polymyxin B or melittin. As determined by the rat agar bead model of lung infection, the SAL1 mutant had a survival defect in vivo since it could not be recovered from the lungs of infected rats 14 days postinfection. Together, these data show that the B. cenocepacia LPS inner core oligosaccharide is needed for in vitro resistance to three structurally unrelated antimicrobial peptides and for in vivo survival in a rat model of chronic lung infection.

Burkholderia cepacia was originally isolated in 1950 as the causative agent of onion soft rot (6) and is now classified as a member of the B. cepacia complex (Bcc), a group of at least nine closely related bacterial species that are phenotypically similar but genetically distinct (11, 33). These metabolically diverse bacteria have been isolated from numerous environmental sources, including soil, water, and plants (14, 31, 32). Due to their metabolic diversity, Bcc members have been extensively studied as potential tools for bioremediation of pollutants, such as trichloroethylene (30). However, over the last 20 years Bcc bacteria have emerged as important opportunistic pathogens, particularly in individuals suffering from cystic fibrosis (CF) (26).

Chronic lung infections develop in CF patients, and treatment of Bcc infections has proven to be difficult due to the inherent resistance of Bcc bacteria to most clinically relevant antibiotics (40). In a subset of CF patients infected with Bcc bacteria, the infection evolves into a fatal, necrotizing pneumonia known as cepacia syndrome (26). This severe clinical outcome is not usually observed with other CF lung pathogens, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Transmission of Bcc bacteria between CF patients has been documented and has led to the segregation of Bcc-infected CF patients (15, 18). All members of the Bcc have been isolated from CF patients; however, in North America Burkholderia cenocepacia is the species that is most commonly found (46) and is therefore the species we focused on in this study.

A remarkable characteristic of Bcc bacteria is their innate resistance to a wide variety of antimicrobial compounds, including their high levels of resistance to antimicrobial peptides (34). Antimicrobial cationic peptides are a group of almost 900 naturally occurring, small, positively charged proteins with antimicrobial activities. They are produced by a variety of species, including invertebrates, plants, and mammals (4). In humans, antimicrobial peptides are part of the innate immune response to bacterial infections and have been implicated in the antimicrobial activities of phagocytes, inflammatory body fluids, and epithelial secretions, including airway epithelial cells (47, 53). Permeabilization of bacterial membranes is a crucial step in the antimicrobial activity of these peptides (4), but recent evidence shows that they also inhibit a variety of essential microbial processes, such as protein, cell wall, and nucleic acid synthesis (5, 43).

Bacteria have a number of different mechanisms to resist the effects of antimicrobial peptides, including alteration of their surface charge, proteolytic degradation, and export of peptides by efflux pumps (3, 44, 48). Some gram-negative bacteria, such as Klebsiella pneumoniae, possess capsular polysaccharides that contribute to antimicrobial peptide resistance (8). In addition, the various components of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) have been shown to be important for the resistance of gram-negative organisms to antimicrobial peptides. LPS O antigen plays a role in the resistance to antimicrobial peptides in Bordetella bronchiseptica (1), while the outer core and inner core regions contribute to the resistance of Yersinia enterocolitica (50) and Escherichia coli (16) to antimicrobial peptides, respectively. In addition, the LPS molecules of many gram-negative organisms are modified upon exposure to antimicrobial peptides, and the modifications contribute to increased bacterial resistance to peptides. In Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, exposure to antimicrobial peptides results in the modification of lipid A with 4-amino-4-deoxy-l-arabinose (Ara4N) (21). Other LPS modifications that confer antimicrobial peptide resistance include palmitoylation and myristoylation of lipid A (22, 52). The Ara4N modification of lipid A is thought to be constitutive in B. cenocepacia and probably critical for its innate resistance to antimicrobial peptides (13), but there may be other mechanisms of resistance.

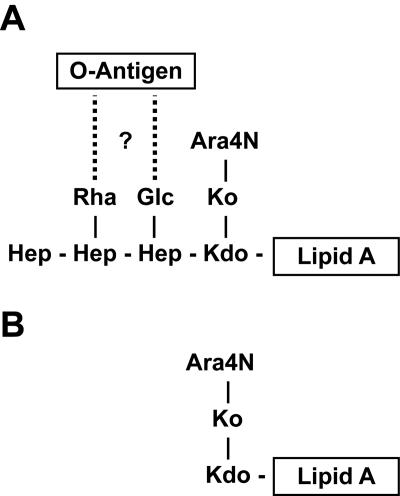

The LPS structure of B. cenocepacia strains has not been completely elucidated. We have investigated the composition and structure of the O antigen in strain K56-2 (42), and the structure of the lipid A moiety of a B. cepacia (formerly genomovar I) strain has recently been reported (49). Also, partial core structures of B. cepacia strains GIFU 645 and ATTC 25416 have been elucidated (19, 28). In Fig. 1A we present a proposed structure for the inner core region in B. cenocepacia, taking into account the high level of conservation of the inner core region in Burkholderia species (19, 27, 38). This region contains at least one residue of deoxy-manno-octulosonic acid, glycero-talo-octulosonic acid, and three glycero-manno-heptoses (Fig. 1A). In addition, the glycero-talo-octulosonic acid residue may be substituted with Ara4N. To better understand the role of LPS in the resistance of B. cenocepacia to antimicrobial peptides, we sought to truncate the LPS molecule by disrupting the biosynthesis pathway of ADP-l-glycero-β-d-manno-heptose. Nucleotide-activated heptose is a precursor for the assembly of the inner core oligosaccharide region of LPS, which is mediated by specific heptosyltransferases. This pathway has been extensively characterized in our laboratory and is highly conserved among gram-negative bacteria (30, 36, 54). Hallmarks of this pathway include the sequential kinase and phosphatase reactions that result first in the formation of d-glycero-β-d-manno-heptose 1,7-biphosphate and then in the synthesis of d-glycero-β-d-manno-heptose 1-phosphate, which are mediated by the enzymes HldE and GmhB, respectively (55). HldE is a bifunctional enzyme that consists of a kinase domain and an ADP transferase domain (36). However, in some bacteria each domain is separately encoded by the genes hldA (kinase) and hldC (ADP transferase) (55), which may or may not be part of the same genetic unit. d-glycero-d-manno-Heptose is further converted into ADP-d-glycero-d-manno-heptose (by the ADP transferase domain of HldE or the HldC protein) and finally into ADP-l-glycero-d-manno-heptose (29). This last step is mediated by the HldD epimerase. A diagram of a truncated form of LPS is shown in Fig. 1B. Although disruption of the ADP-l-glycero-d-manno-heptose synthesis pathway should not affect the Ara4N modifications of lipid A, phosphate groups covalently linked to the heptose moieties of the inner core have been shown to bind divalent cations that are important for maintaining proper outer membrane stability and permeability (23). For some bacteria, including P. aeruginosa, the heptose moieties are believed to be essential for bacterial survival (56). In this paper, we describe identification of the B. cenocepacia hldA and hldD genes and show that a mutant strain lacking a complete LPS core oligosaccharide is sensitive to the antimicrobial peptides polymyxin B, melittin, and human neutrophil peptide 1 (HNP-1) and cannot survive in a rat model of lung infection.

FIG. 1.

Structural diagram of full-length and heptoseless lipopolysaccharide in B. cenocepacia. The tentative structure of lipid A-core oligosaccharide was determined from the information available for B. cepacia strains GIFU 645 (28) and ATCC 25416 (19). (A) Dotted lines and the question mark indicate that the linkage with the O antigen in strain K56-2 is not known. (B) Proposed lipid A-core structure of the heptoseless LPS mutant SAL1. Kdo, deoxy-manno-octulosonic acid; Ko, glycero-talo-octulosonic acid.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

E. coli and B. cenocepacia strains used in this study are described in Table 1. All strains were grown at 37°C either on LB plates containing 1.6% Bacto agar or in liquid LB medium. B. cenocepacia strains were also grown on Mueller-Hinton (MH) agarose plates containing 1.3% agarose for testing susceptibility to HNP-1 (see below). Trimethoprim (50 μg/ml for E. coli and 100 μg/ml for B. cenocepacia) and chloramphenicol (30 μg/ml for E. coli and 100 μg/ml for B. cenocepacia) were used for selection of mutations and maintenance of complementing plasmids. Kanamycin (25 μg/ml) was used to maintain E. coli mutants FAM3 and SAL7. Gentamicin (50 μg/ml) was used during triparental mating to select against the donor and helper strains. All antibiotics were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristicsa | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli strains | ||

| DH5α | F− φ80 lacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 endA1 recA1 hsdR17 (rK− mK+) supE44 thi-1 ΔgyrA96 relA1 | Laboratory stock |

| SY327 | araD Δ(lac pro) argE(Am) recA56 rifR nalA λ pir | 38 |

| SØ874 | lacZ trp Δ(sbcB-rfb) upp relA rpsL λ− | 40 |

| FAM3 | SØ874, ΔhldE1 Kmr | 37 |

| SAL7 | SØ874, ΔhldD Kmr | This study |

| Burkholderia cenocepacia strains | ||

| K56-2 | ET12 clone, CF clinical isolate | BCRRCb |

| SAL1 | K56-2, hldA::pSL5 Tpr | This study |

| SAL2 | K56-2, cysteine synthase B::pSL12 Tpr | This study |

| RSF19 | K56-2, wbxE::pRF201 Tpr | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pGP-ΩTp | oriR6K Tpr | This study |

| pRF200 | oriR6K Tpr | This study |

| pRF201 | pRF200, 320-bp wbxE mutagenesis fragment | This study |

| pRK2013 | RK2 derivative, Kmrmob+tra+oricolE1 | 17 |

| pSL5 | pGP-ΩTp, 273-bp hldA mutagenesis fragment | This study |

| pSL12 | pGP-ΩTp, 315-bp cysteine synthase B mutagenesis fragment | This study |

| pSCrhaB2 | pMLBAD with PRha (rhamnose-inducible promoter), Tpr | 9 |

| pSL3 | pSCrhaB2, B. cenocepacia hldA | This study |

| pSL6 | pSCrhaB2, chloramphenicol resistance cassette, Tpr Cmr | This study |

| pSL7 | pSL6, B. cenocepacia hldDA | This study |

| pSL8 | pSL6, B. cenocepacia hldA | This study |

| pSL9 | pSL6, B. cenocepacia hldD | This study |

Tp, trimethoprim; Cm, chloramphenicol; Km, kanamycin; Ap, ampicillin.

BCRRC, B. cepacia Complex Research and Referral Repository for Canadian CF Clinics.

Mutagenesis and cloning.

All plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1. B. cenocepacia mutants SAL1 and SAL2 were constructed using the pGP-ΩTp system, which will be described in greater detail elsewhere (Flannagan and Valvano, unpublished data). Briefly, an internal fragment of the targeted gene was used to generate single-crossover insertions of a suicide plasmid into the gene of interest. Omega fragments incorporated into the gene prevented expression of downstream genes. The plasmid was introduced into B. cenocepacia strain K56-2 by triparental mating, and mutants were selected by growth on trimethoprim. Putative mutants were first screened by PCR for disruption of the gene and then confirmed by Southern blot hybridization. Three PCR-positive, Southern blot-positive clones were screened for both mutants to ensure that the mutant phenotypes were consistent. RSF19 was generated by insertional inactivation of wbxE using pRF200. This plasmid is a suicide plasmid in B. cenocepacia, which upon integration into wbxE resulted in a polar mutation (Flannagan and Valvano, unpublished). Internal fragments were amplified using the following primers (underlined regions indicate restriction enzyme cut sites used for cloning, and the enzymes are indicated in parentheses): for SAL1, primers 5′-TTATCTAGAGATGCTCGACCGTTACTGG-3′ (XbaI) and 5′-TACTCTAGAAGCACGCGCAGCTTGATCG-3′ (XbaI); for SAL2, primers 5′-TAATTCTAGATGTAAACCAGCACCGGCACG-3′ (XbaI) and 5′-TACGTCTAGAATGGGCGGGCACACCGTCG-3′ (XbaI); and for RSF19, primers 5′-TTTGAATTCCAGAGCCGTCAAGGCCGG-3′ (EcoRI) and 5′-TTTGTCGACACCGGTCGCACGTGGACG-3′ (SalI). The fragments were amplified with Proofstart DNA polymerase (QIAGEN Inc., Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) with the following thermal cycling conditions: 95°C for 3 min, followed by 29 cycles of 95°C for 40 s, 60°C for 40 s, and 72°C for 40 s and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. Restriction enzymes and T4 DNA ligase for cloning experiments were obtained from Roche Diagnostics, Laval, Quebec, Canada.

SAL7 was constructed using the one-step PCR method of Datsenko and Wanner (12). The kanamycin cassette was amplified using primers 5′-TGAGACAGTCTCTGACACCATAATTCAAAGGTTACAGTTAGTGTAGGCTGG AGCTGCTTCG-3′ and 5′-ACGCGTCGCGGTTCAGCCAGGCCATATACTCCGTGACGCCCATATGAATATCCTCCTTAGA-3′. The cassette was amplified using QIAGEN Proofstart DNA polymerase with the following thermal cycling conditions: 94°C for 2 min, followed by 28 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 57°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 90 s and a final extension at 72°C for 8 min.

For complementation experiments in E. coli, hldA and hldD from B. cenocepacia were cloned into the pSCrhaB2 (9) and pSL6 vectors, respectively. The pSL6 vector is a derivative of pSCrhaB2 that contains a chloramphenicol resistance cassette cloned into the Asp700 restriction enzyme site of the multiple cloning site. For complementation experiments with B. cenocepacia, genes were cloned into pSL6. For amplification of hldA primers 5′-TAATCGTCATATGAATACTCTTCGCGAAGTCG-3′ (NdeI) and 5′-TAATTCTAGACCGCCGAATGCGCTCAGTG-3′ (XbaI) were used; for amplification of hldD primers 5′-TAATCCCATATGACCCTCATCGTCACCGGC-3′ (NdeI) and 5′-TAATTCTAGACAACGCGCCGGTTTAAAC-3′ (XbaI) were used; and for amplification of hldAD primers 5′-TAATCGTCATATGAATACTCTTCGCGAAGTCG-3′ (NdeI) and 5′-TAATTCTAGACAACGCGCCGGTTTAAAC-3′ (XbaI) were used. Individual genes were amplified using QIAGEN Proofstart DNA polymerase with the following thermal cycling conditions: 95°C for 2 min, followed by 29 cycles of 95°C for 40 s, 60°C for 40 s, and 72°C for 1 min and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. Amplification of hldA and hldD together was done using the thermal cycling conditions described above with the extension time lengthened to 2 min. Reverse transcription-PCR was performed as previously described (42) to determine cotranscription of the hldA and hldD genes.

LPS analysis.

LPS was extracted as previously described (24, 35), with some modifications. Briefly, bacteria were grown on plates overnight. Cells were scraped from the plates, resuspended in phosphate-saline buffer, lysed in buffer containing 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 4% β-mercaptoethanol, and 1 M Tris (pH 6.8), and boiled for 10 min. The lysate was subsequently treated with DNase I for 30 min at 37°C and with proteinase K for 60 min at 60°C and stored at −20°C. LPS was separated on 16.4% Tricine-SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels and fixed overnight in buffer containing 60% methanol and 10% acetic acid. The gels were stained in a solution containing 0.67% AgNO3.

Disk and drop diffusion assays.

Disk diffusion assays were used to test the susceptibility of B. cenocepacia strains to novobiocin and SDS. Briefly, logarithmic-phase cells were spread on agar plates, and dry disks were applied to the surfaces. Eight microliters of a solution containing 0.25 to 20 mg/ml novobiocin or 10% SDS or distilled H2O was added to the disks in triplicate. The plates were incubated for 16 h at 37°C, and zones of inhibition were measured. A similar assay was used to test for susceptibility to the α-defensin HNP-1 (Sigma). HNP-1 was dissolved in 0.2% bovine serum albumin (BSA)-0.01% acetic acid. Cells were spread on MH agarose plates, and 5-μl drops of peptide (25, 50, and 100 μg/ml) or buffer were pipetted directly onto the surfaces of the plates in duplicate. The drops were allowed to dry, and the plates were inverted, incubated for 16 h at 37°C, and scanned.

MIC50 assay.

Bacteria were grown in liquid cultures overnight, diluted into fresh media the next morning, and grown to the logarithmic phase (optical density at 600 nm, 0.2 to 0.4). Bacterial density was determined by measuring the optical density at 600 nm, and cells were diluted to obtain a concentration of 2 × 105 CFU/ml. Polymyxin B (Sigma) and melittin (Sigma) were dissolved in 0.2% BSA-0.01% acetic acid buffer to obtain a concentration of 5.12 mg/ml and then serially diluted to obtain a concentration of 10 μg/ml. Bacterial cultures (200 μl) were treated in Eppendorf tubes with 22 μl of peptide dilutions or buffer (final peptide concentrations, 0 to 512 μg/ml). The cultures were incubated at 37°C for 16 h, and the final density was determined by determining the optical density at 600 nm. All dilutions were tested in triplicate. The MIC50 was defined as the lowest peptide concentration at which growth was inhibited by 50% or more. Alternatively, stationary-phase cells were used in the assay.

Polymyxin B sensitivity assay.

Logarithmic-phase cells were diluted to obtain a concentration of 2 × 105 CFU/ml, and 100 μl (2 × 104 CFU) of each bacterial culture was treated with 100 μg/ml polymyxin B in 0.2% BSA-0.01% acetic acid buffer or with buffer alone. The cultures were incubated for 2 h at 37°C with rotation in a Barnstead Thermolyne LABQUAKE (Barnstead International, Dubuque, Iowa). After treatment, viable cells were enumerated. For time course analysis experiments, 400-μl cultures were used, 10-μl aliquots were removed at each time, and viable cells were enumerated.

Rat agar bead model of chronic lung infection.

The competitive index of the SAL1 mutant was determined as previously described (25) by using the rat agar bead model of chronic infection (10). Briefly, the lungs of six rats were inoculated intratracheally with agar beads containing approximately 2 × 104 wild-type and mutant cells at a 1:1 ratio. An additional four rats were infected with 2 × 104 mutant cells alone. Fourteen days postinfection, the lungs were removed and homogenized, and the numbers of viable wild-type and mutant bacteria in the lungs were determined on Trypticase soy agar and Trypticase soy agar containing 100 μg/ml trimethoprim.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Identification of hld genes in B. cenocepacia.

Analysis of the genomic sequence of B. cenocepacia strain J2315 resulted in the discovery of two genes homologous to hldA and hldD, which putatively encode a heptokinase and an epimerase, respectively. Downstream of hldA and hldD is a gene that encodes a product with homology to cysteine synthase B, while directly upstream of hldA we identified two other genes that encode polypeptides with homology to the UDP-glucose dehydrogenase and a putative conserved membrane protein (Fig. 2). These genes were annotated as BCAL2943 to BCAL2947 by the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/B_cenocepacia/) and are located in chromosome 1; they are close to one another and are transcribed in the same direction, suggesting that they form a five-gene operon. In our studies, we used B. cenocepacia strain K56-2, which is clonally related to J2315 (33) but is much easier to manipulate genetically. PCR amplifications confirmed that this region was identical in these two strains. We also confirmed by reverse transcription-PCR that hldA and hldD are cotranscribed (data not shown), which supports the hypothesis that they are part of an operon.

FIG. 2.

Genomic organization of the hld gene cluster. The solid boxes represent internal fragments used for mutagenesis. The dotted line represents the region amplified by reverse transcription-PCR, demonstrating cotranscription of hldA and hldD.

HldA is a heptokinase, and HldD is an epimerase.

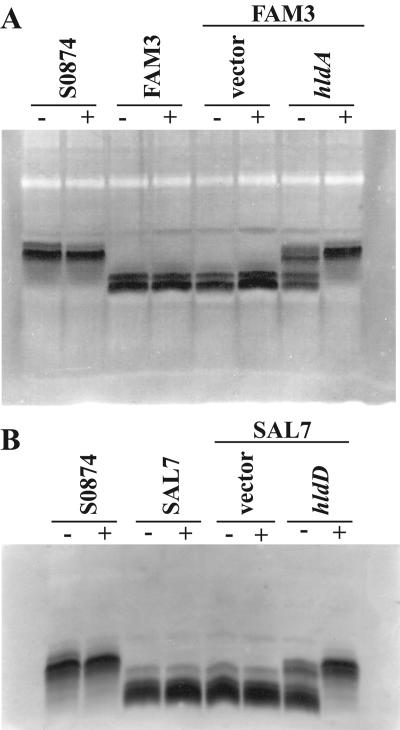

To confirm that hldA encodes a heptokinase, we cloned the gene into the rhamnose-inducible expression vector pSCrhaB2 (Table 1) and tested the ability of the recombinant plasmid to complement E. coli ΔhldE1 mutant FAM3 (36). In E. coli, the heptokinase activity is in the amino-terminal domain (known as the HldE1 domain) of the bifunctional HldE protein (36). The FAM3 mutant strain has a partial deletion of the hldE gene that eliminates the heptokinase activity, while the rest of the ADP-heptose pathway remains functional (36). As shown in Fig. 3A, FAM3 produced shorter, faster-migrating lipid A-core oligosaccharide bands, reflecting the loss of heptose sugars in the LPS core moiety. In contrast, FAM3(pSL3) produced lipid A-core oligosaccharide bands whose migration was identical to the migration observed for parental strain SØ874. Restoration of the parental lipid A-core oligosaccharide phenotype was complete in the presence of the inducer rhamnose and partial in the absence of the inducer. No changes were observed in the LPS profile of the FAM3 mutant transformed with the vector control. These results demonstrate that the B. cenocepacia hldA gene encodes a protein with heptokinase activity. A similar experiment was performed using E. coli ΔhldD strain SAL7, and the results confirmed that the B. cenocepacia hldD gene encodes an epimerase (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

Complementation of the E. coli LPS mutants with B. cenocepacia genes. (A) E. coli SØ874 heptokinase (hldE1) mutant FAM3 complemented with the B. cenocepacia hldA gene. (B) E. coli SØ874 epimerase (hldD) mutant SAL7 complemented with the B. cenocepacia hldD gene. − and +, absence and presence, respectively, of 0.2% rhamnose for induction of gene expression.

B. cenocepacia hldA mutant produces a truncated LPS.

A mutagenesis strategy was used to create B. cenocepacia polar mutants by integration of a plasmid containing transcriptional and translational stops through a single recombination event (Flannagan and Valvano, unpublished). Both hldA and the cysteine synthase B genes were successfully targeted by this method, resulting in mutants SAL1 and SAL2, respectively (Fig. 2). Since we did not expect the protein encoded by the cysteine synthase B gene to play a role in ADP-l-glycero-d-manno-heptose synthesis or antimicrobial peptide resistance, SAL2 was used as an internal control in all experiments.

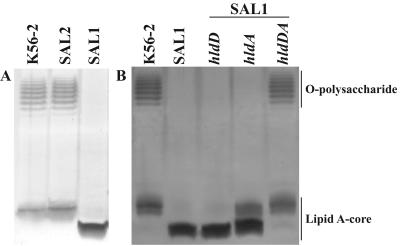

LPS from the SAL1 and SAL2 mutants was purified and compared to that of parental strain K56-2 (Fig. 4A). SAL2 and K56-2 produced LPS with identical profiles, confirming that the protein encoded by the cysteine synthase B gene is not involved in the synthesis of LPS, as expected. The ladder-like banding pattern corresponded to the presence of polymeric O antigen, as we have previously shown for strain K56-2 (42). In contrast, SAL1 produced a faster-migrating lipid A-core oligosaccharide band and no polymeric O antigen, which is consistent with a loss of heptoses in the inner core. This defect could be rescued when a complementing plasmid containing both hldD and hldA was transformed into SAL1 (Fig. 4B). Plasmids containing either of the two genes alone could not rescue the LPS defective phenotype (Fig. 4B). However, in the presence of a functional hldA alone, SAL1 produced a small amount of full-length core, and when the gel was overstained, a very small amount of O antigen could be visualized (data not shown). Heptosyltransferases have also been shown to transfer d-glycero-d-manno-heptose, albeit at much lower rates than l-glycero-d-manno-heptose (58). This could account for the low level of complementation with HldA alone. SAL1 was also more sensitive that K56-2 to treatment with novobiocin and SDS (data not shown), which indicated that this mutant exhibits a deep-rough LPS phenotype (2, 51).

FIG. 4.

LPS phenotypes of SAL1 and SAL2 and complementation of SAL1. (A) Disruption of hldA results in LPS with a smaller core and no O antigen, and disruption of the downstream gene does not alter the LPS phenotype. (B) Complementation of SAL1. Both hldA and hldD are required for complementation of SAL1. Gene expression by complementing plasmids was induced with 0.2% rhamnose.

B. cenocepacia LPS core mutant is sensitive to the antimicrobial peptides polymyxin B, melittin, and HNP-1.

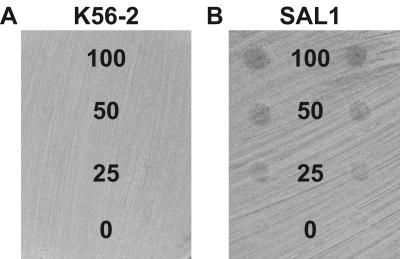

As B. cenocepacia is highly resistant to antimicrobial peptides, we determined whether production of heptoseless LPS resulted in increased sensitivity to peptides. The MIC50s of the antimicrobial peptides polymyxin B and melittin were determined for K56-2 and SAL1 grown to the mid-logarithmic phase (Table 2). Compared to the MIC50s for the parental strain, the MIC50s of polymyxin B and melittin for SAL1 were >16-fold and >64-fold lower, respectively. Similar results were obtained with stationary-phase cells exposed to polymyxin B (data not shown). We also assayed SAL1 and K56-2 for susceptibility to the α-defensin HNP-1. Since we could not obtain sufficient amounts of HNP-1 for an MIC50 assay in liquid culture, we performed a semiquantitative growth inhibition assay on agar plates, as described in Materials and Methods. At all concentrations of HNP-1 tested (0 to 100 μg/ml) the growth of K56-2 was not inhibited (Table 2 and Fig. 5). In contrast, the growth of SAL1 was inhibited at a concentration of 25 μg/ml (Table 2), as shown by a clear halo where HNP-1 was spotted onto the plate (Fig. 5). Together, these results demonstrate that a heptoseless LPS is associated with B. cenocepacia sensitivity to three structurally unrelated peptides.

TABLE 2.

Antimicrobial peptide MIC50s for K56-2 and SAL1

| Strain | MIC50 (μg/ml)

|

Growth inhibition by HNP-1 (μg/ml)a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymyxin B | Melittin | ||

| K56-2 | >512 | >512 | >100 |

| SAL1 | 32 | 8 | 25 |

Observed as haloes of growth inhibition on plates where the peptide was directly spotted onto the plates (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Heptoseless B. cenocepacia is sensitive to HNP-1. (A) Growth of K56-2 was not impaired at any concentration of HNP-1 tested. (B) Growth of SAL1 was inhibited at all concentrations of HNP-1 tested, as visualized by circles of growth inhibition where the plate was inoculated with HNP-1. The numbers indicate the concentrations of HNP-1 (in μg/ml) spotted in each row.

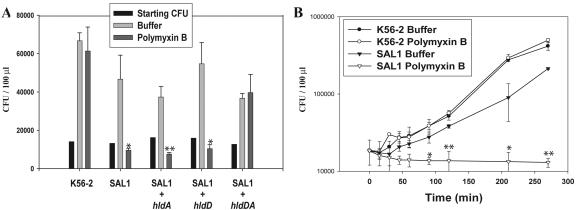

We investigated in greater detail the sensitivity of SAL1 to polymyxin B using an assay in which strains were challenged with 100 μg/ml of the peptide for 2 h, followed by enumeration of viable cells. Strain K56-2 did not exhibit any growth differences in the presence and in the absence of 100 μg/ml of polymyxin B (Fig. 6A). In contrast, SAL1 exhibited a fourfold reduction in growth after treatment with polymyxin B compared to untreated cells. A similar reduction was not observed for strain SAL2 (data not shown), demonstrating that the cysteine synthase B gene, downstream of hldD, does not encode a protein needed for resistance to polymyxin B. Additionally, complementation studies showed that both hldD and hldA are required for growth in the presence of polymyxin B, but that complementation with either gene individually does not confer resistance (Fig. 6A). The growth of the complemented strains was somewhat slower than the growth of K56-2, possibly due to the energetic constraints of maintaining plasmids and the overexpression of plasmid-encoded HldA and HldD proteins.

FIG. 6.

Heptoseless B. cenocepacia is sensitive to polymyxin B. (A) Number of CFU prior to challenge (Starting CFU) and 2 h after incubation in the absence (Buffer) or presence (Polymyxin B) of 100 μg/ml polymyxin B. (B) Time course analysis of growth in the absence (solid symbols) or presence (open symbols) of 100 μg/ml polymyxin B for 4.5 h. The data points and error bars indicate means and standard deviations of data from one representative experiment done in triplicate. Significant differences were determined using unpaired t tests. One asterisk indicates that the P value is <0.05 for the statistical difference between the polymyxin B and buffer treatments, and two asterisks indicate that the P value is <0.001.

The sensitivity of the heptoseless mutant to polymyxin B was believed to be bacteriostatic. To confirm this, we modified the assay to include a time course analysis. Figure 6B shows that although there was a gradual decrease in viable SAL1 bacteria over 4.5 h, the number of bacteria remaining after 4.5 h was similar to the number in the initial inoculum. We concluded from these results that the SAL1 mutant is sensitive to polymyxin B and that the effect of polymyxin B is primarily bacteriostatic.

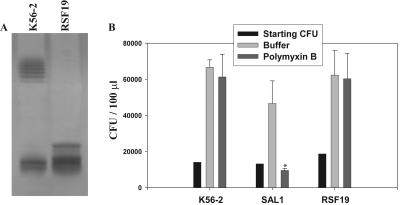

Loss of polymeric O antigen does not result in sensitivity to polymyxin B.

In other organisms, such as B. bronchiseptica, the O antigen is important for resistance to antimicrobial peptides (1). To determine whether sensitivity to polymyxin B in the B. cenocepacia SAL1 mutant was due to the absence of either the complete LPS core or O antigen or both, an additional mutant that was unable to produce polymeric O antigen was constructed. In this mutant, the B. cenocepacia K56-2 wbxE gene was inactivated, resulting in strain RSF19. The wbxE gene encodes a glycosyltransferase necessary for assembly of the O-antigen subunits (42). In the clonally related strain B. cenocepacia J2315, an insertion element interrupts this gene and is responsible for the lack of O-antigen expression (42). RSF19 produced LPS with a complete lipid A-core oligosaccharide and another band due to a partial O-antigen subunit linked to the lipid A-core oligosaccharide (42) (Fig. 7A). RSF19 was resistant to polymyxin B (Fig. 7B) and melittin (data not shown). Therefore, we concluded that the loss of lipid A-core oligosaccharide heptoses and not the loss of polymeric O antigen was responsible for sensitivity to the peptides tested. This conclusion is also supported by the observation that B. cenocepacia strain J2315, which lacks O antigen, is also highly resistant to antimicrobial peptides (Loutet and Valvano, unpublished results). To date, we have been unable to construct a mutant strain devoid of O antigen because genes that are typically targeted to create O-antigen mutants, such as wecA or waaL, are found in operons with genes involved in synthesis of other LPS components or are duplicated. Additional mutant strains must be constructed in order to test the importance of LPS outer core sugars for antimicrobial peptide resistance. In other organisms, such as Y. enterocolitica and Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae, the outer core residues contribute to antimicrobial peptide resistance (45, 50).

FIG. 7.

Lack of O antigen does not impair resistance to polymyxin B. (A) LPS phenotypes of K56-2 and RSF19. (B) Number of CFU prior to challenge (Starting CFU) and 2 h after incubation in the absence (Buffer) or presence (Polymyxin B) of 100 μg/ml polymyxin B. The data points and error bars indicate means and standard deviations of data from one representative experiment done in triplicate. Significant differences were determined using unpaired t tests. The asterisk indicates that the P value is <0.05 for the statistical difference between the polymyxin B and buffer treatments.

SAL1 does not survive in the rat agar bead model of chronic lung infection.

The in vivo survival of SAL1 was investigated using the rat agar bead model of chronic lung infection, both in competition with wild-type strain K56-2 and by itself. Agar beads containing a 1:1 ratio of K56-2 and SAL1 were inoculated intratracheally. SAL1 was unable to compete with K56-2, as no mutant colonies were recovered from the lungs of six rats 14 days postinfection, whereas 1.4 × 104 ± 2.7 ×104 CFU/ml wild-type organisms were recovered at this time. An additional four rats were infected with SAL1 alone, and again no SAL1 colonies were recovered from the lungs of the any of the rats. These experiments clearly demonstrated that loss of a complete lipid A-core oligosaccharide has a marked effect on the in vivo survival of B. cenocepacia.

Concluding remarks.

Our results demonstrate that the complete lipid A-core oligosaccharide of B. cenocepacia is required for resistance to the antimicrobial peptides polymyxin B, melittin, and HNP-1 in vitro and for bacterial survival in vivo. The effects that we observed here may be indirect. Conceivably, in this study other components of LPS that play a role in antimicrobial peptide resistance and in vivo survival were disrupted. The ability to phosphorylate heptose residues of the inner core has been shown to contribute to antimicrobial peptide resistance and virulence in S. enterica (57). Loss of phosphorylation sites via disruption of LPS heptose residues in B. cenocepacia may have the same effect. Additionally, outer membrane proteins that are important for antimicrobial peptide resistance and in vivo survival may be destabilized in SAL1 due to the severe LPS truncation. This is consistent with the increased sensitivity of the heptoseless mutant to hydrophobic antibiotics like novobiocin and SDS. Despite the possibility of an indirect effect, the observations described in this paper support the hypothesis that a novel inhibitory molecule capable of targeting the synthesis of heptose sugars prior to their incorporation into the LPS could enhance the ability of the immune system to clear a B. cenocepacia infection.

Although the heptoseless mutant SAL1 is more susceptible to the effects of polymyxin B than the parental strain, it is not as sensitive to polymyxin B as other bacteria. SAL1 cells can still survive in the presence of 100 μg/ml of polymyxin B. By comparison, E. coli O157 incubated in the presence of 12.5 μg/ml polymyxin B is killed within 30 min (41), and an S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strain constitutively expressing Ara4N substitutions of lipid A was found to have a polymyxin B MIC of 6.3 μg/ml (20). Presumably, the presence of the Ara4N in the lipid A of SAL1 contributes to protection of these bacteria from polymyxin B killing. However, given that resistance is still high (MIC50 of polymyxin B, 32 μg/ml), it is likely that the resistance of B. cenocepacia to polymyxin B and other antimicrobial peptides is multifactorial. We are currently investigating whether the stability of one or more outer membrane proteins is compromised in our heptoseless LPS mutant and whether these proteins are associated with resistance to antimicrobial peptides.

In a recent study, Gronow et al. (19) constructed a deep-rough mutant of B. cepacia strain ATCC 25416 (genomovar I) with a truncated core and concluded that this structural change did not affect the virulence of the bacterium. Our results do not support this conclusion, but they are in agreement with a report by Burtnick and Woods (7), which showed that in the non-Bcc organism Burkholderia pseudomallei, the LPS core oligosaccharide is also necessary for resistance to polymyxin B. Further investigations are under way in our laboratory to fully characterize the genetic determinants of antimicrobial peptide resistance in B. cenocepacia.

Acknowledgments

We thank F. McArthur for providing strain FAM3 and J. Parkhill for providing the mutation of B. cenocepacia J2315.

This work was funded by grants from the Canadian Bacterial Diseases Network and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (to M.A.V.) and by the Special Program Grant Initiative “In Memory of Michael O'Reilly” funded by the Canadian Cystic Fibrosis Foundation and the Cardiovascular and Respiratory Health Institute of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (to M.A.V. and P.A.S.). S.A.L. and R.S.F. were supported by scholarships from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and the Canadian Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, respectively. M.A.V. holds a Canada Research Chair in Infectious Disease and Microbial Pathogenesis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Banemann, A., H. Deppisch, and R. Gross. 1998. The lipopolysaccharide of Bordetella bronchiseptica acts as a protective shield against antimicrobial peptides. Infect. Immun. 66:5607-5612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bayer, M. E., J. Koplow, and H. Goldfine. 1975. Alterations in envelope structure of heptose-deficient mutants of Escherichia coli as revealed by freeze-etching. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 72:5145-5149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belas, R., J. Manos, and R. Suvanasuthi. 2004. Proteus mirabilis ZapA metalloprotease degrades a broad spectrum of substrates, including antimicrobial peptides. Infect. Immun. 72:5159-5167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brogden, K. A. 2005. Antimicrobial peptides: pore formers or metabolic inhibitors in bacteria? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:238-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brötz, H., G. Bierbaum, K. Leopold, P. E. Reynolds, and H. G. Sahl. 1998. The lantibiotic mersacidin inhibits peptidoglycan synthesis by targeting lipid II. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:154-160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burkholder, W. H. 1950. Sour skin, a bacterial rot of onion bulbs. Phytopathology 40:115-117. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burtnick, M. N., and D. E. Woods. 1999. Isolation of polymyxin B-susceptible mutants of Burkholderia pseudomallei and molecular characterization of genetic loci involved in polymyxin B resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:2648-2656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campos, M. A., M. A. Vargas, V. Regueiro, C. M. Llompart, S. Alberti, and J. A. Bengoechea. 2004. Capsule polysaccharide mediates bacterial resistance to antimicrobial peptides. Infect. Immun. 72:7107-7114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cardona, S. T., and M. A. Valvano. 2005. An expression vector containing a rhamnose-inducible promoter provides tightly regulated gene expression in Burkholderia cenocepacia. Plasmid 54:219-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cash, H. A., D. E. Woods, B. McCullough, W. G. Johanson Jr., and J. A. Bass. 1979. A rat model of chronic respiratory infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 119:453-459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coenye, T., P. Vandamme, J. J. LiPuma, J. R. W. Govan, and E. Mahenthiralingam. 2003. Updated version of the Burkholderia cepacia complex experimental strain panel. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:2797-2798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Soyza, A., C. D. Ellis, C. M. A. Khan, P. A. Corris, and R. D. de Hormaeche. 2004. Burkholderia cenocepacia lipopolysaccharide, lipid A, and proinflammatory activity. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 170:70-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Di Cello, F., A. Bevivino, L. Chiarini, R. Fani, D. Paffetti, S. Tabacchioni, and C. Dalmastri. 1997. Biodiversity of a Burkholderia cepacia population isolated from the maize rhizosphere at different plant growth stages. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:4485-4493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duff, A. J. 2002. Psychological consequences of segregation resulting from chronic Burkholderia cepacia infection in adults with CF. Thorax 57:756-758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farnaud, S., C. Spiller, L. C. Moriarty, A. Patel, V. Gant, E. W. Odell, and R. W. Evans. 2004. Interactions of lactoferricin-derived peptides with LPS and antimicrobial activity. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 233:193-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Figurski, D. H., and D. R. Helinski. 1979. Replication of an origin-containing derivative of plasmid RK2 dependent on a plasmid function provided in trans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:1648-1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Govan, J. R., P. H. Brown, J. Maddison, C. J. Doherty, J. W. Nelson, M. Dodd, A. P. Greening, and A. K. Webb. 1993. Evidence for transmission of Pseudomonas cepacia by social contact in cystic fibrosis. Lancet 342:15-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gronow, S., C. Noah, A. Blumenthal, B. Lindner, and H. Brade. 2003. Construction of a deep-rough mutant of Burkholderia cepacia ATCC 25416 and characterization of its chemical and biological properties. J. Biol. Chem. 278:1647-1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gunn, J. S., K. B. Lim, J. Krueger, K. Kim, L. Guo, M. Hackett, and S. I. Miller. 1998. PmrA-PmrB-regulated genes necessary for 4-aminoarabinose lipid A modification and polymyxin resistance. Mol. Microbiol. 27:1171-1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo, L., K. B. Lim, J. S. Gunn, B. Bainbridge, R. P. Darveau, M. Hackett, and S. I. Miller. 1997. Regulation of lipid A modifications by Salmonella typhimurium virulence genes phoP-phoQ. Science 276:250-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo, L., K. B. Lim, C. M. Poduje, M. Daniel, J. S. Gunn, M. Hackett, and S. I. Miller. 1998. Lipid A acylation and bacterial resistance against vertebrate antimicrobial peptides. Cell 95:189-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hancock, R. E. W., D. N. Karunaratne, and C. Bernegger-Egli. 1994. Molecular organization and structural role of outer membrane macromolecules, p. 263-279. In J. M. Ghuysen and R. Hackenbeck (ed.), Bacterial cell wall, vol. 27. Elsevier Science, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hitchcock, P. J., and T. M. Brown. 1983. Morphological heterogeneity among Salmonella lipopolysaccharide chemotypes in silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. J. Bacteriol. 154:269-277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hunt, T. A., C. Kooi, P. A. Sokol, and M. A. Valvano. 2004. Identification of Burkholderia cenocepacia genes required for bacterial survival in vivo. Infect. Immun. 72:4010-4022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Isles, A., I. Maclusky, M. Corey, R. Gold, C. Prober, P. Fleming, and H. Levison. 1984. Pseudomonas cepacia infection in cystic fibrosis: an emerging problem. J. Pediatr. 104:206-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Isshiki, Y., K. Kawahara, and U. Zähringer. 1998. Isolation and characterisation of disodium (4-amino-4-deoxy-β-l-arabinopyranosyl)-(1→ 8)-(d-glycero-α-d-talo-oct-2-ulopyranosylonate)-(2→4)-(methyl 3-deoxy-d-manno-oct-2-ulopyranosid)onate from the lipopolysaccharide of Burkholderia cepacia. Carbohydr. Res. 313:21-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Isshiki, Y., U. Zähringer, and K. Kawahara. 2003. Structure of the core-oligosaccharide with a characteristic d-glycero-α-d-talo-oct-2-ulosylonate-(2→4)-3-deoxy-d-manno-oct-2-ulosonate [α-Ko-(2→4)-Kdo] disaccharide in the lipopolysaccharide from Burkholderia cepacia. Carbohydr. Res. 338:2659-2666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kneidinger, B., C. Marolda, M. Graninger, A. Zamyatina, F. McArthur, P. Kosma, M. A. Valvano, and P. Messner. 2002. Biosynthesis pathway of ADP-l-glycero-β-d-manno-heptose in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 184:363-369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krumme, M. L., K. N. Timmis, and D. F. Dwyer. 1993. Degradation of trichloroethylene by Pseudomonas cepacia G4 and the constitutive mutant strain G4 5223 PR1 in aquifer microcosms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:2746-2749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leff, L. G., R. M. Kernan, J. V. McArthur, and L. J. Shimkets. 1995. Identification of aquatic Burkholderia (Pseudomonas) cepacia by hybridization with species-specific rRNA gene probes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:1634-1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.LiPuma, J. J., T. Spilker, T. Coenye, and C. F. Gonzalez. 2002. An epidemic Burkholderia cepacia complex strain identified in soil. Lancet 359:2002-2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mahenthiralingam, E., T. Coenye, J. W. Chung, D. P. Speert, J. R. W. Govan, P. Taylor, and P. Vandamme. 2000. Diagnostically and experimentally useful panel of strains from the Burkholderia cepacia complex. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:910-913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mahenthiralingam, E., T. A. Urban, and J. B. Goldberg. 2005. The multifarious, multireplicon Burkholderia cepacia complex. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:144-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marolda, C. L., M. F. Feldman, and M. A. Valvano. 1999. Genetic organization of the O7-specific lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis cluster of Escherichia coli VW187 (O7:K1). Microbiology 145:2485-2495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McArthur, F., C. E. Andersson, S. Loutet, S. L. Mowbray, and M. A. Valvano. 2005. Functional analysis of the glycero-manno-heptose 7-phosphate kinase domain from the bifunctional HldE protein, which is involved in ADP-l-glycero-d-manno-heptose biosynthesis. J. Bacteriol. 187:5292-5300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller, V. L., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1988. A novel suicide vector and its use in construction of insertion mutations: osmoregulation of outer membrane proteins and virulence determinants in Vibrio cholerae requires toxR. J. Bacteriol. 170:2575-2583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Molinaro, A., C. De Castro, R. Lanzetta, A. Evidente, M. Parrilli, and O. Holst. 2002. Lipopolysaccharides possessing two l-glycero-d-manno-heptopyranosyl-α-(1→5)-3-deoxy-d-manno-oct-2-ulopyranosonic acid moieties in the core region. The structure of the core region of the lipopolysaccharides from Burkholderia caryophylli. J. Biol. Chem. 277:10058-10063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neuhard, J., and E. Thomassen. 1976. Altered deoxyribonucleotide pools in P2 eductants of Escherichia coli K-12 due to deletion of the dcd gene. J. Bacteriol. 126:999-1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nzula, S., P. Vandamme, and J. R. Govan. 2002. Influence of taxonomic status on the in vitro antimicrobial susceptibility of the Burkholderia cepacia complex. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 50:265-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oie, S., A. Kamiya, M. Tomita, S. Matsusaki, A. Katayama, and A. Iwasaki. 1997. In vitro susceptibility of Escherichia coli O157 to several antimicrobial agents. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 20:584-585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ortega, X., T. A. Hunt, S. Loutet, A. D. Vinion-Dubiel, A. Datta, B. Choudhury, J. B. Goldberg, R. Carlson, and M. A. Valvano. 2005. Reconstitution of O-specific lipopolysaccharide expression in Burkholderia cenocepacia strain J2315, which is associated with transmissible infections in patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Bacteriol. 187:1324-1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patrzykat, A., C. L. Friedrich, L. Zhang, V. Mendoza, and R. E. Hancock. 2002. Sublethal concentrations of pleurocidin-derived antimicrobial peptides inhibit macromolecular synthesis in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:605-614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peschel, A., M. Otto, R. W. Jack, H. Kalbacher, G. Jung, and F. Götz. 1999. Inactivation of the dlt operon in Staphylococcus aureus confers sensitivity to defensins, protegrins, and other antimicrobial peptides. J. Biol. Chem. 274:8405-8410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ramjeet, M., V. Deslandes, F. St. Michael, A. D. Cox, M. Kobisch, M. Gottschalk, and M. Jacques. 2005. Truncation of the lipopolysaccharide outer core affects susceptibility to antimicrobial peptides and virulence of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae serotype 1. J. Biol. Chem. 280:39104-39114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reik, R., T. Spilker, and J. J. LiPuma. 2005. Distribution of Burkholderia cepacia complex species among isolates recovered from persons with or without cystic fibrosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:2926-2928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schutte, B. C., and P. B. McCray, Jr. 2002. β-Defensins in lung host defense. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 64:709-748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shafer, W. M., X. Qu, A. J. Waring, and R. I. Lehrer. 1998. Modulation of Neisseria gonorrhoeae susceptibility to vertebrate antibacterial peptides due to a member of the resistance/nodulation/division efflux pump family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:1829-1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Silipo, A., A. Molinaro, P. Cescutti, E. Bedini, R. Rizzo, M. Parrilli, and R. Lanzetta. 2005. Complete structural characterization of the lipid A fraction of a clinical strain of B. cepacia genomovar I lipopolysaccharide. Glycobiology 15:561-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Skurnik, M., R. Venho, J. A. Bengoechea, and I. Moriyon. 1999. The lipopolysaccharide outer core of Yersinia enterocolitica serotype O:3 is required for virulence and plays a role in outer membrane integrity. Mol. Microbiol. 31:1443-1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smit, J., Y. Kamio, and H. Nikaido. 1975. Outer membrane of Salmonella typhimurium: chemical analysis and freeze-fracture studies with lipopolysaccharide mutants. J. Bacteriol. 124:942-958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tran, A. X., M. E. Lester, C. M. Stead, C. R. H. Raetz, D. J. Maskell, S. C. McGrath, R. J. Cotter, and M. S. Trent. 2005. Resistance to the antimicrobial peptide polymyxin requires myristoylation of Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium lipid A. J. Biol. Chem. 280:28186-28194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tsutsumi-Ishii, Y., and I. Nagaoka. 2003. Modulation of human beta-defensin-2 transcription in pulmonary epithelial cells by lipopolysaccharide-stimulated mononuclear phagocytes via proinflammatory cytokine production. J. Immunol. 170:4226-4236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Valvano, M. A., C. L. Marolda, M. Bittner, M. Glaskin-Clay, T. L. Simon, and J. D. Klena. 2000. The rfaE gene from Escherichia coli encodes a bifunctional protein involved in biosynthesis of the lipopolysaccharide core precursor ADP-l-glycero-d-manno-heptose. J. Bacteriol. 182:488-497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Valvano, M. A., P. Messner, and P. Kosma. 2002. Novel pathways for biosynthesis of nucleotide-activated glycero-manno-heptose precursors of bacterial glycoproteins and cell surface polysaccharides. Microbiology 148:1979-1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Walsh, A. G., M. J. Matewish, L. L. Burrows, M. A. Monteiro, M. B. Perry, and J. S. Lam. 2000. Lipopolysaccharide core phosphates are required for viability and intrinsic drug resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 35:718-727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yethon, J. A., J. S. Gunn, R. K. Ernst, S. I. Miller, L. Laroche, D. Malo, and C. Whitfield. 2000. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium waaP mutants show increased susceptibility to polymyxin and loss of virulence in vivo. Infect. Immun. 68:4485-4491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zamyatina, A., S. Gronow, C. Oertelt, M. Puchberger, H. Brade, and P. Kosma. 2000. Efficient chemical synthesis of the two anomers of ADP-l-glycero- and d-glycero-d-manno-heptopyranose allows the determination of the substrate specificities of bacterial heptosyltransferases. Angew. Chem. Int. 39:4150-4153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]