Abstract

We identified and characterized the iron-binding protein Dps from Campylobacter jejuni. Electron microscopic analysis of this protein revealed a spherical structure of 8.5 nm in diameter, with an electron-dense core similar to those of other proteins of the Dps (DNA-binding protein from starved cells) family. Cloning and sequencing of the Dps-encoding gene (dps) revealed that a 450-bp open reading frame (ORF) encoded a protein of 150 amino acids with a calculated molecular mass of 17,332 Da. Amino acid sequence comparison indicated a high similarity between C. jejuni Dps and other Dps family proteins. In C. jejuni Dps, there are iron-binding motifs, as reported in other Dps family proteins. C. jejuni Dps bound up to 40 atoms of iron per monomer, whereas it did not appear to bind DNA. An isogenic dps-deficient mutant was more vulnerable to hydrogen peroxide than its parental strain, as judged by growth inhibition tests. The iron chelator Desferal restored the resistance of the Dps-deficient mutant to hydrogen peroxide, suggesting that this iron-binding protein prevented generation of hydroxyl radicals via the Fenton reaction. Dps was constitutively expressed during both exponential and stationary phase, and no induction was observed when the cells were exposed to H2O2 or grown under iron-supplemented or iron-restricted conditions. On the basis of these data, we propose that this iron-binding protein in C. jejuni plays an important role in protection against hydrogen peroxide stress by sequestering intracellular free iron and is expressed constitutively to cope with the harmful effect of hydrogen peroxide stress on this microaerophilic organism without delay.

The microaerophilic gram-negative bacterium Campylobacter jejuni is a major cause of bacterial diarrhea in both developed and developing countries. Infection with C. jejuni usually causes an acute, self-limited gastroenteritis characterized by diarrhea, fever, nausea, and abdominal cramps. The clinical aspects range from watery to severely bloody diarrhea (3, 26). In addition to acute gastrointestinal disease, infection with C. jejuni is recognized as the most important trigger of Guillain-Barré syndrome (2). Despite its great importance in human health and economy, little is known of its virulence determinants and mechanisms of survival in the environment.

In their natural environment, whether in the gastrointestinal tracts of mammalian hosts or in the external environment during transmission, it is likely that C. jejuni cells are faced with growth-limiting or potentially lethal conditions, such as iron limitation and oxidative stresses.

Iron is an essential nutrient for most organisms. It is required as a cofactor by several enzymes and as a catalyst in electron transport processes. However, in the presence of oxygen, iron is able to generate oxygen radicals that can damage DNA, proteins, and membrane lipids (19, 23, 32). Iron homeostasis therefore has to be carefully balanced, and this is achieved by tightly controlling its uptake, metabolism, and storage (12). The intracellular amount of free ferrous iron is controlled mainly by the iron-binding protein ferritin, which incorporates ferrous iron and which stores in its central cavity the ferric iron that is formed after oxidation (21).

Ferritins consist of 24 identical or similar subunits that assemble into a spherical shell (21). The protein plays a substantial role in the storage of iron and protects the bacteria from metal toxicity (9, 44). In C. jejuni, ferritin (Cft) has also been identified and shown to play an important role in iron storage under iron-restricted conditions (47).

Recently, iron-binding protein particles other than ferritins have been identified in several bacterial species (4, 11, 34, 43, 52). These protein particles form a dodecamer of a smaller size than ferritins and are thought to belong to the Dps (DNA-binding protein from starved cells) protein family in their amino acid sequence homology (11, 43).

In Escherichia coli, when the bacterial cells are under oxidative or nutritional stress conditions, Dps protein is expressed and binds DNA without apparent sequence specificity, forming extremely stable complexes, resulting in protection of DNA against oxidative stress (4, 18, 30). Dps is also shown to possess an iron-binding property, and the protective effect of Dps on DNA is thought to be also exerted through the ability to nullify the toxic combination of Fe(II) and H2O2 (56).

Helicobacter pylori, a close relative to C. jejuni (17), possesses a neutrophil-activating protein (HP-NAP) belonging to the family of Dps proteins (43). HP-NAP was shown to bind iron in vitro, and growth of the HP-NAP mutant was more sensitive to oxygen than the wild-type strain. (33, 43).

In this study, we report on the identification and characterization of C. jejuni Dps and demonstrate its involvement in defense against hydrogen peroxide stress by constructing a Dps-deficient mutant.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, media, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. C. jejuni was grown on Mueller-Hinton agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) in an anaerobic box (Mitsubishi Gas Chemical Co., Inc., Tokyo, Japan) at 42°C under microaerobic atmosphere (Anaeropack Campylo; Mitsubishi Gas Chemical Co., Inc.). For analysis of liquid culture, C. jejuni was grown in Mueller-Hinton broth at 60 rpm in an orbital shaker under microaerobic atmosphere. If necessary, 10 or 20 μM deferoxamine mesylate (Desferal; Sigma Chemical Co.) or 20 or 40 μM ferrous sulfate (Wako Pure Chemicals, Osaka, Japan) was added to the medium. E. coli was grown aerobically in Luria broth (containing, per liter, 10 g of tryptone [Difco], 5 g of yeast extract [Difco], and 5 g of sodium chloride) or on Luria agar at 37°C. When appropriate, kanamycin (30 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (25 μg/ml), ampicillin (50 μg/ml), and isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (Sigma Aldrich Japan, Tokyo, Japan) (1 mM) were added to the medium.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristicsa | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | F−endA1 hsdR17 supE44 thi-1 recA1 Δ(argF-lacZYA)U169 (φ80d lacZ ΔM15) gyrA96 λ− | 20 |

| BL21(DE3) | BL21 λ (DE3) under lac control promoter | 40 |

| C. jejuni | ||

| 81-176 | Clinical isolate | 10 |

| TIS-1 | dps mutant of C. jejuni 81-176 | This study |

| SNA-1 | cft mutant of C. jejuni 81-176 | 47 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pGEM-T Easy | AprlacZ general cloning vector | Promega |

| pUC19 | Apr parental cloning vector | 54 |

| pET21b | Apr gene expression vector by T7 RNA polymerase carrying a C-terminal His6 tag sequence | Novagen |

| pRY108 | Kmr shuttle plasmid | 55 |

| pRY109 | Apr Camr; cat gene in BamHI site of pUC18 | 55 |

| pTIS-1 | Apr 1.1-kbp PCR-amplified fragment of C. jejuni 81-176 containing dps in pGEM-T Easy | This study |

| pTIS-3 | Kmr shuttle plasmid; 1.1-kb EcoRI fragment of dps gene in pRY108 | This study |

| pTIS-10 | Apr 2.5-kbp PCR-amplified fragment of C. jejuni 81-176 containing dps in pGEM-T Easy | This study |

| pTIS-15 | Apr Camr pTIS-10 dps::cat insertion; the Camr cassette is in the same transcriptional orientation as dps | This study |

| pTIS-21 | pET21b derivative containing dps | This study |

Apr, ampicillin resistance; Camr, chloramphenicol resistance; Kmr, kanamycin resistance.

General genetic methods.

Restriction enzymes and T4 DNA polymerase were purchased from Takara Shuzo Co., Ltd. (Kyoto, Japan), and Toyobo Co., Ltd. (Osaka, Japan). Taq DNA polymerase was purchased from Promega. Calf-intestine alkaline phosphatase was purchased from Biolabs, Inc. (Beverly, Mass.). The Ready-To-Go PCR beads for PCR amplification were purchased from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Piscataway, N.J.). Oligonucleotides used for PCR amplification were purchased from Japan Flour Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). The PCR conditions were 94°C for 60 s, 55°C (for primer pairs consisting of primers TI-1 and TI-2 and primers OVDPS-3 and OVDPS-4) or 59°C (for primer pair TI-5 and TI-6) for 60 s, and 72°C for 60 s for 30 cycles. Plasmid DNA was isolated by using the Wizard Plus Mini Prep (Promega) or alkaline lysis method (37). Chromosomal DNA of C. jejuni was purified by using a genomic prep cells and tissue DNA isolation kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Purification of Dps protein.

Cultures of C. jejuni grown on Mueller-Hinton agar plates (100 plates) were harvested in phosphate-buffered saline buffer. The cells were collected by centrifugation at 6,500 × g for 20 min, resuspended in sterile distilled water, and kept at room temperature for 2 h for water extraction. The cell suspension was centrifuged at 75,000 × g for 1 h. The resulting supernatant was filtered through a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter unit (Minisart; Superdex, Gottingen, Germany) and centrifuged at 125,000 × g for 3 h. The pellet was suspended in 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) and applied to a Superdex column (HiLoad 26/60 Superdex 200 prep grade; Amersham). The elution of the protein was monitored by measuring the absorbance at 280 nm. The eluted peaks were checked by electron microscopy for the presence of Dps particles.

N-terminal amino acid sequence analysis.

Amino acid sequence analysis was performed by using model 437A and 477A gas-phase sequencers (Applied Biosystems).

Cloning and sequencing of the dps gene.

From the result of the N-terminal amino acid sequence, degenerate oligonucleotide primers were synthesized. By PCR amplification of chromosomal DNA from C. jejuni strain 81-176 with these primers, a 63-bp DNA fragment was amplified. This fragment was cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector, and its nucleotide sequence was determined. Translation of the nucleotide sequence corresponded exactly to the N-terminal sequence obtained from the purified Dps protein of C. jejuni. The corresponding region of the C. jejuni NCTC 11168 genome was searched, and a 450-bp ORF had exactly the same sequence. Plasmid pTIS-1 containing the whole ORF of the dps gene was constructed, and its DNA sequencing was determined. DNA-sequencing reactions were performed on plasmid template with ABI Prism BigDye terminator cycle sequencing ready reaction kits (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) and an ABI PRISM 377 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems).

Plasmid construction.

A 1.1-kb DNA fragment containing the dps gene was PCR amplified by using primer pair TI-1 (5′-CCTGGTGTGGAAGTTGGAAAG-3′) and TI-2 (5′-CTCCAAATTTACTGCGTCCACT-3′) and ligated into pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, Madison, Wis.), resulting in pTIS-1. Plasmid pTIS-1 was digested with EcoRI, and a 1.1-kb DNA fragment containing the dps gene was extracted. This fragment was ligated into an EcoRI site of shuttle plasmid pRY108, resulting in pTIS-3. A 2.5-kb DNA fragment containing the dps gene was PCR amplified by using primer pair TI-5 (5′-GATGAGGTAAAAAGTGGAGATATA-3′) and TI-6 (5′-CAAAGATTATTTCTTAGGCCAAAATC-3′) and cloned into pGEM-T Easy vector, resulting in pTIS-10. pTIS-10 was partially digested by HindIII and blunted with T4 DNA polymerase. A 0.8-kb PvuII cat cassette of pRY109 was ligated into a HindIII site of pTIS-10. A plasmid clone with a cat cassette insertion at the blunted HindIII site within the dps gene was selected and designated pTIS-15. The dps gene was PCR amplified with primer pair OVDPS-3 (5′-GGCATATGTCAGTTAAAAACAATTAT-3′) and OVDPS-4 (5′-GGCTCGAGCATTTTGCAAGCACCCTGT-3′). These primers contain a 5′ NdeI or XhoI restriction enzyme site (underlined) for cloning in pET21b, and the PCR product was cloned into this vector, resulting in pTIS-21. All of the genes were amplified from the chromosome of C. jejuni 81-176.

Overexpression of the dps gene in E. coli.

C-terminal His6-tagged Dps recombinant protein was purified as follows. E. coli BL21(DE3) was transformed with pTIS-21 by using the method described by Hanahan (20). The dps gene in E. coli strain BL21(DE3) was expressed by adding 1 mM IPTG as described previously (40). Bacterial cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed in phosphate-buffered saline buffer, and resuspended in 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0). Cells were broken by sonication and centrifuged at 75,000 × g for 1 h. The supernatant containing Dps protein was filtered through a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter unit and transferred to the His-trap kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden). Dps protein was eluted in elution buffer (10 mM Na2HPO4, 10 mM NaH2PO4, 500 mM Imidazol, 500 mM NaCl [pH 7.5]), dialyzed against 20 mM Tris HCl buffer (pH 7.0)-150 mM NaCl-0.1 mM EDTA, and stored at 4°C.

DNA-binding assay.

A DNA-binding assay was performed as described previously (4, 53). Briefly, 5, 10, and 30 μg of recombinant Dps was added to 200 ng of plasmid pUC19 or C. jejuni genomic DNA in TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]) to achieve a final volume of 10 μl. The DNA-protein mixture was incubated for 30 min at 37°C, electrophoresed through a 1.0% agarose gel in TBE buffer (Tris-borate-EDTA), and stained with ethidium bromide. Purified E. coli Dps, kindly provided by Yamamoto, was used as a positive control.

Iron staining.

Iron staining was performed as described elsewhere (14, 52). Briefly, Fe(NH4)2(SO4) · 6H2O was added to the samples at a final concentration of 1 mM, and the mixture was incubated on ice for 30 min. The mixture was resolved by vertical nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) (8% polyacrylamide). The gels were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue or 1 mM 3-(2-pyridyl)-5,6-bis(2-[5-furyl sulfonic acid])-1,2,4-triazine (Ferene S; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) and 15 mM thioglycolic acid (Sigma Chemical Co.) in 2% (vol/vol) acetic acid.

Measurement of the iron content of Dps.

Iron-loaded Dps was prepared by following the method of Yamamoto et al. (52) with some modifications. Briefly, 100 μg of the recombinant Dps/ml was incubated with 500 μM ferrous ammonium sulfate in 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.0)-150 mM NaCl-0.1 mM EDTA at room temperature for 30 min. The iron-loaded Dps was purified on a PD-10 column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) equilibrated with the same buffer, and the iron content of the protein was determined by following the method of Jung and Parker (25) by using 1,10-Phenanthroline (Sigma Chemical Co.) as a chromogen. The results (see “Overexpression and characterization of Dps” below) are means for triplicates.

Production of polyclonal antiserum.

Polyclonal antiserum against Dps was prepared after immunization of Japan white rabbits with purified Dps protein from the Dps-overexpressing E. coli cells as described previously (48).

Natural transformation of C. jejuni.

Transformation of C. jejuni was performed as described previously (47), with some modifications to overcome the restriction barrier of C. jejuni (5, 31, 49, 50), following the method of Donahue (15). Briefly, bacterial cells grown on Mueller-Hinton agar for 6 h were pelleted, and then the pellet was resuspended in 5 volumes of extraction buffer (20 mM Tris-acetate [pH 7.9], 50 mM potassium acetate, 5 mM Na2EDTA, 1 mM DTT, protease inhibitor cocktail) and sonicated on ice. The supernatants were removed and designated CFE (cell extract of C. jejuni). Plasmid pTIS-15 extracted from the E. coli strain was mixed with the CFE and S-adenosyl-L-methionine (Sigma Chemical Co.) at a final concentration of 200 μM and incubated overnight at 37°C. pTIS-15 was extracted with phenol-chloroform, precipitated with ethanol, and dissolved in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) to achieve a final concentration of 300 ng/μl. The plasmid was then used for natural transformation.

Southern blot hybridization.

Chromosomal DNA from C. jejuni strains (81-176 and TIS-1) were digested with ScaI restriction enzyme, resolved in 0.7% agarose gel in TBE buffer, and blotted onto nylon membrane. A 1.1-kb DNA fragment containing the dps gene was generated by PCR (with primers TI-1 and TI-2), labeled with digoxigenin-11-dUTP, and used as the hybridization probe. The method for prehybridization and hybridization and the washing conditions were the same as described previously (37), and the procedure for colorimetric detection of hybridized DNA was performed by using the DIG system (Roche Diagnostic Co., Indianapolis, Ind.).

Western blotting.

Protein samples were denatured and separated on 13.6% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-PAGE by the method of Laemmli (29). Western blotting was performed as described previously (24) by using rabbit polyclonal first antibody against Dps at a final dilution of 1:1,000 and alkaline phosphate-conjugated secondary antibody at a final dilution of 1:500. When immunoreactive bands were visualized by using the ECL Plus Western blotting detection system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), first antiserum against Dps at a final dilution of 1:2,000 and secondary horseradish peroxidase labeled antibody at a final dilution of 1:4,000 were used.

H2O2 sensitivity assay.

H2O2 sensitivity was examined by using a disk diffusion assay or a liquid culture method. Disk-diffusion assays were performed by following the published procedures (47). Briefly, 5 × 107 bacterial cells were spread on Mueller-Hinton agar, and Whatman 3MM paper disks (5 mm in diameter) containing various amounts of H2O2 were applied to the surfaces of the plates. After 48 h of incubation at 42°C, the clear zones surrounding the disks were measured. The data represents the distances from the edge of the disks to the end of the clear zone, where growth begins. Sensitivity to H2O2 was evaluated by measuring the minimum concentrations at which a growth inhibition zone around the disk containing H2O2 first appeared. A liquid culture method was adapted from the method of Purdy et al. (36). Briefly, cells were grown in Mueller-Hinton medium overnight, adjusted to 1 × 109 cells/ml, challenged with H2O2 to a final concentration of 5 mM, and incubated at 37°C. If necessary, cells were pretreated with 40 mM Desferal for 5 min before exposure to H2O2. Viable numbers of bacteria present in each aliquot were determined via dilutional plating on Mueller-Hinton agar plates. Challenge was terminated by the addition of catalase at 400 U/ml in each diluent.

Estimation of protein concentrations.

Protein concentrations were determined by the bicinchoninic acid method by using a kit (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) and bovine serum albumin (BSA) as the standard (38).

Electron microscopy.

The morphology of the purified Dps protein was examined under a JEM 2000EX electron microscopy as described previously (48).

Computer searches.

Sequencing data from the genome of C. jejuni NCTC 11168 was available at the Sanger Centre web site. Protein sequences were compared with database sequences by using the BLAST programs.

Phylogenetic characterization.

Phylogenetic analysis was conducted with the amino acid sequences of ferritins, bacterioferritins, and Dps family proteins. A phylogenetic tree was constructed by using the CLUSTAL program (version 1.5) (42).

RESULTS

Purification of a Dps-like protein from C. jejuni.

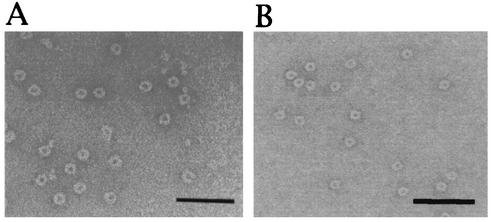

During our studies of ferritin in C. jejuni, we observed other particle-like structures in electron micrographs that resembled Dps protein complexes. The putative Dps-like particles were purified for further characterization and are here referred to as Dps. Dps particles were purified from water extracts of C. jejuni 81-176 by ultracentrifugation and gel filtration. Each fraction of the gel filtration was subject to electron microscopy to examine for the presence of Dps particles. This particle, which measures 8.5 nm in diameter and has an electron-dense core (Fig. 1A), is smaller than ferritin particles of C. jejuni, which measure 11.5 nm in diameter (48). SDS-PAGE revealed that the particle consists of a single 17-kDa polypeptide (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Electron micrographs of negatively stained C. jejuni Dps. The Dps particles were purified from cell extracts of C. jejuni (A) and E. coli overexpressing the dps gene (B). Bars, 50 nm.

Cloning and sequencing of the dps gene.

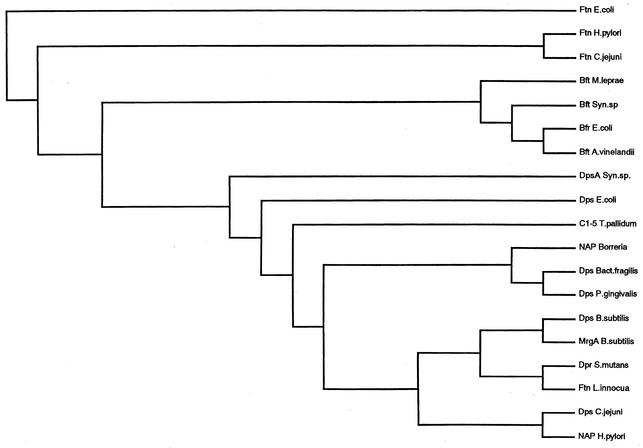

Based on the result of the N-terminal amino acid sequence analysis, the 63-bp nucleotide sequence encoding the 21 N-terminal amino acids of Dps was determined. The region containing this 63-bp nucleotide sequence was localized in the genome of C. jejuni NCTC 11168 and showed that a 450-bp ORF contained the same sequence as this 63-bp fragment. A 1.1-kb DNA fragment containing the whole ORF of this putative dps gene of C. jejuni 81-176 was cloned into pGEM-T Easy vector. The clone was confirmed by DNA sequencing to contain the 450-bp ORF encoding Dps. The molecular mass of the deduced Dps was 17,332 Da, similar to the estimates from denaturing PAGE (data not shown). The primary structure of C. jejuni Dps has a high similarity to those of HP-NAP (16, 43), E. coli Dps (4), and other members of the Dps family (6, 11, 13, 35, 51). Comparison of amino acid sequences revealed that the iron-binding motif (His 25, His 37, Asp 41, Asp 52, Glu 56) proposed by Ilrai et al. (22) was conserved in the C. jejuni Dps protein (data not shown). A phylogenetic analysis was conducted, comparing the deduced amino acid sequence with those of ferritins, bacterioferritins, and Dps family proteins. The result indicated that C. jejuni Dps belonged to the Dps family of proteins rather than to the ferritin or bacterioferritin group (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic relationships of ferritins, bacterioferritins, and the Dps family. The database accession numbers are as follows: E. coli ferritin (Ftn E. coli), p23887; Ftn H. pylori, A49694; Ftn C. jejuni, S77578; Micobacterium leprae bacterioferritin (Bft M. leprae), p43315; Synechococcus sp. bacterioferritin (Bft Syn. sp.), S77468; Bft E. coli, p11054; Azotobacter vinelandii bacterioferritin (Bft A. vinelandii), p22759; Synechococcus sp. DpsA protein (DpsA Syn. sp.), A44631; Dps E. coli, A46401; C1-5 antigen of Treponema pallidum (C1-5 T. pallidum), p16665; neutrophil-activating protein of Borreria (NAP Borreria), A70186; Bacteroides fragilis Dps protein (Dps Bact. fragilis), 2621338A; Porphilomonus gingivalis Dps protein (Dps P. gingivalis), AB025779; Bacillus subtilis Dps protein (Dps B. subtilis), H69618; B. subtilis MrgA protein (MrgA B. subtilis), p37960; S. mutans Dpr protein (Dpr. S. mutans), JC7274; Ftn L. innocua, p80725; Dps C. jejuni, D81300; and HP-NAP (NAP H. pylori), p43313.

Overexpression and characterization of Dps.

To prepare Dps protein particles needed for further characterization, a His-tagged Dps-overexpressing E. coli strain was constructed by using the T7 RNA polymerase expression system. A large amount of Dps protein was purified from this strain by using the His-trap kit, and these recombinant protein particles showed the same structure as the native Dps particles (Fig. 1B).

To determine whether C. jejuni Dps protein possesses DNA-binding activity, a gel mobility shift assay was performed with plasmid pUC19. However, there was no change in DNA migration in the presence of C. jejuni Dps, indicating the absence of a DNA-binding property of C. jejuni Dps. The addition of C. jejuni Dps also did not affect the mobility of C. jejuni genomic DNA (data not shown).

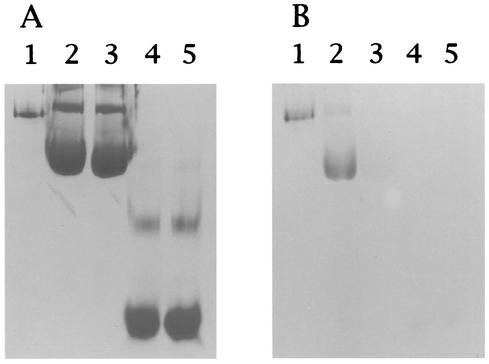

The iron-binding ability of Dps was examined. Nondenaturing PAGE was performed, and the gels were stained with Ferene S, which specifically stains iron as described previously (14, 52). Dps preincubated with Fe(NH4)2(SO4) · 6H2O and ferritin (positive control) were stained with Ferene S. Dps without preincubation with Fe(NH4)2(SO4) · 6H2O and BSA with or without preincubation with Fe(NH4)2(SO4) · 6H2O (negative control) were not stained with Ferene S (Fig. 3). Thus, it was demonstrated that Dps has iron-binding capacity.

FIG. 3.

Identification of the iron-binding ability of the C. jejuni Dps protein. (A) Nondenaturing PAGE stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. (B) Nondenaturing PAGE stained with Ferene S. Lanes: 1, ferritin; 2, C. jejuni Dps preincubated with Fe(NH4)2(SO4) · 6H2O; 3, C. jejuni Dps alone; 4, BSA preincubated with Fe(NH4)2(SO4) · 6H2O; 5, BSA alone.

Analysis of the iron content of recombinant C. jejuni Dps revealed that this protein contains 0.122 ± 0.013 iron atoms per subunit, according to the method of Jung and Parker (25). When 100 μg of the recombinant Dps/ml was incubated with ferrous ammonium sulfate at concentrations higher than 250 μM, a brown precipitate was formed, indicating the saturation point of the iron-binding capacity of this protein. To investigate the maximum number of iron atoms bound by Dps, 100 μg of the recombinant Dps/ml was saturated with 500 μM ferrous ammonium sulfate and purified on a PD-10 column, and the iron content of the protein was determined. The maximum number of iron atoms bound by Dps was estimated to be 40.1 ± 3.1 per subunit. This value was similar to those of Listeria innocua ferritin (11), HP-NAP (43), and Streptococcus mutans Dpr (53). A His tag was added to the C terminus of the Dps protein. His-tagged Dps particles showed the same structure as the native Dps particles under electron microscopic examination. The predicted iron-binding motif resides in the N-terminal half of this protein, and the amount of iron bound by His-tagged Dps was almost the same as those of other Dps family proteins. From these results, it does not seem that the presence of the His tag affects the iron-binding capacity of this recombinant Dps protein.

Construction of a dps mutant of C. jejuni.

To investigate the role of the Dps protein, a dps mutant was constructed. Plasmid pTIS-15, containing the dps gene disrupted by the insertion of the chloramphenicol resistance gene cassette into the HindIII site, was treated with C. jejuni CFE and used for natural transformation. A number of chloramphenicol-resistant transformants of strain 81-176 were obtained. One of the transformants, designated TIS-1, was used for further analysis. Analysis by PCR amplification and Southern blotting confirmed that the mutated DNA was integrated into the appropriate position of the chromosome of TIS-1 by a double crossover (data not shown). Inactivation of the dps gene in TIS-1 was confirmed by immunoblot analysis with anti-Dps antiserum (data not shown).

H2O2 sensitivity of the dps mutant.

To assess the contribution of Dps to hydrogen peroxide stress resistance of C. jejuni, disk inhibitory assays were performed as described previously (47). Growth of the Dps-deficient mutant strain was significantly inhibited by H2O2 in comparison with that of the wild-type strain and the ferritin-deficient mutant strains (Table 2). The minimum concentration of H2O2 at which the growth of the Dps-deficient mutant was inhibited was 16 times lower than that of wild type and the ferritin-deficient mutant.

TABLE 2.

Hydrogen peroxide sensitivity of dps mutant

| Strainb | Disk sensitivity to H2O2 at a concn (nmole) ofa:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.13 | 6.25 | 12.5 | 25 | 50 | 100 | |

| W.T. | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 ± 0.0 |

| cft | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 ± 0.0 |

| dps | 0.0 | 2.0 ± 0.0 | 2.5 ± 0.50 | 3.6 ± 0.47 | 5.7 ± 0.28 | 7.1 ± 1.1 |

The data represent the distances in millimeters from the edges of the discs to the ends of the clear zones, where growth begins. Data shown are the means and standard deviation values of results of triplicate experiments.

W.T., C. jejuni 81-176; cft, ferritin-deficient mutant of 81-176 (SNA-1); dps, Dps-deficient mutant of 81-176 (TIS-1).

To investigate whether the dps gene is responsible for protection against H2O2, the shuttle plasmid pTIS-3 containing the wild-type dps gene was introduced into the Dps-deficient mutant of C. jejuni. Unexpectedly, this plasmid did not complement the H2O2 sensitivity of the Dps-deficient mutant. Restriction endonuclease site analysis and PCR analysis of the plasmid DNA isolated from the transformants revealed that the plasmid had undergone rearrangements in C. jejuni (data not shown). The reason for this was obscure, but a similar phenomenon was observed and reported in the case of superoxide dismutase cloning in Campylobacter coli previously (36).

Effects of Desferal on the H2O2 sensitivity of the dps mutant.

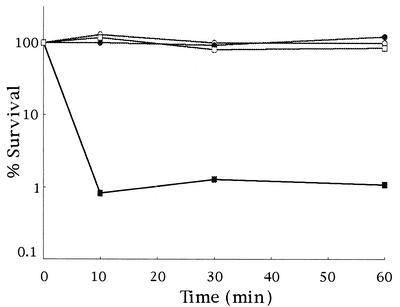

To investigate the role of this iron-binding protein Dps in the resistance of C. jejuni to H2O2, the iron chelator Desferal was added to Dps-deficient mutant when the cells were challenged with H2O2 in liquid culture, following the method of Keyer et al. (27). When the Dps-deficient mutant cells were not pretreated with Desferal, a 2-log decline in the percentage of survivors occurred within 10 min during the challenge (Fig. 4). When the mutant was pretreated with Desferal, it displayed a survival pattern similar to that of the parental strain. These results strongly suggested that the iron-binding ability of Dps contributed to the resistance of C. jejuni to H2O2.

FIG. 4.

Effect of the iron chelator Desferal on survival of the dps mutant strain under H2O2 stress. C. jejuni strain 81-176 (•), dps mutant (TIS-1) (▪), strain 81-176 pretreated with 40 mM Desferal (○), and a dps mutant pretreated with 40 mM Desferal (□) were challenged with 5 mM H2O2, and viability was determined using plate counts. Numbers of surviving bacteria are represented as the percentage of the original inoculum. Similar results were obtained reproducibly in at least three separate experiments.

Expression of Dps under various growth conditions and during H2O2 stress.

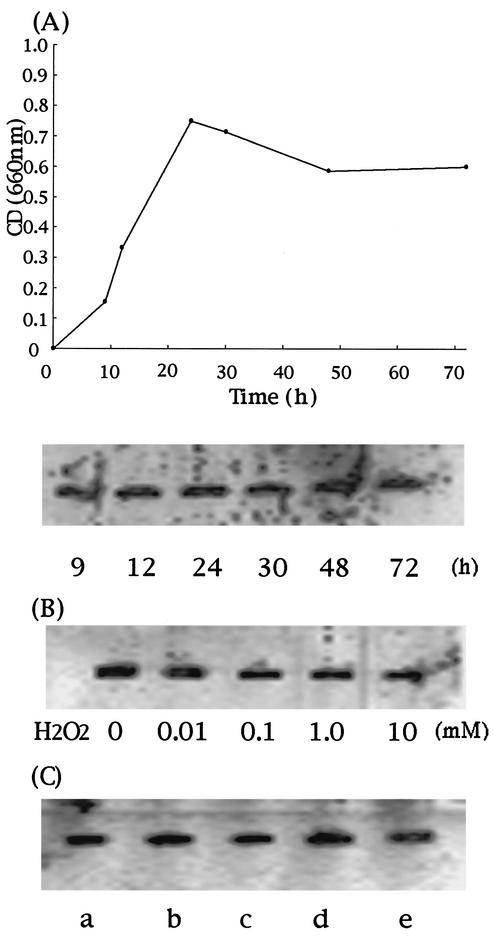

To investigate the expression of Dps under normal growth conditions, immunoblot analysis was performed with samples of C. jejuni grown in Mueller-Hinton broth. The results of Western blotting showed that Dps is constitutively expressed during exponential and stationary phases of growth (Fig. 5A). To investigate the possible effect of H2O2 stress on the production of Dps, bacterial cells that had been grown for about 9 h were exposed to H2O2 and incubated microaerobically at 37°C for 10 or 30 min. No induction was observed under hydrogen peroxide stress (Fig. 5B). To compare the expression of Dps under iron-supplemented or iron-restricted conditions, bacterial cells were grown in Mueller-Hinton medium supplemented with various concentrations of ferrous sulfate or the iron chelator Desferal, as described previously (46). There was no difference in the level of expression of Dps under the tested iron conditions (Fig. 5C).

FIG. 5.

Western blotting analysis of the expression of Dps of C. jejuni strain 81-176 under various growth conditions and peroxide stress. In each experiment, the cell pellets were resuspended in protein loading buffer to give a final concentration of 3 × 109 cells/ml. From each sample, 10 μl was separated on SDS-PAGE and probed with anti-Dps antibody. Immunoreactive bands were visualized by using the ECL Plus Western blotting detection system. (A) Growth curve of C. jejuni strain 81-176 in Mueller-Hinton medium and the expression of Dps at various time points (9 to 72 h) under normal growth conditions. (B) Expression of Dps under the exposure to hydrogen peroxide stress. Bacterial cells were exposed to various concentrations of H2O2 for 10 min. Similar results were obtained when cells were exposed to H2O2 for 30 min (data not shown). (C) Expression of Dps in C. jejuni grown in low- and high-iron media for 24 h. Lanes: a, 20 μM Desferal; b, 10 μM Desferal; c, normal growth conditions; d, 20 μM ferrous sulfate; e, 40 μM ferrous sulfate.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we purified an iron-binding protein, Dps, from C. jejuni, cloned and sequenced the dps gene encoding this protein, and constructed a Dps-deficient mutant to investigate the role of the dps gene in hydrogen peroxide stress resistance.

Electron microscopy revealed that the Dps protein forms spherical oligomers similar in size and feature to those of other Dps family proteins. X-ray crystallographic analyses or computed structure prediction of E. coli Dps, HP-NAP, Bacillus anthracis Dlp-1 and Dlp-2, and L. innocua ferritin revealed that they consist of 12 subunits (dodecamers) (18, 22, 34, 43).

The primary structure of C. jejuni Dps protein showed homology to other Dps family proteins. Phylogenetic analysis also showed that this protein is more closely related to the Dps family proteins than to other iron-binding protein families (ferritin and bacterioferritin) consisting of 24 subunits (41).

The purified Dps possessed iron-binding property in vitro, but lacked DNA-binding ability, as judged by gel mobility shift assay. The putative iron-binding motifs proposed in HP-NAP and L. innocua ferritin (22) are highly conserved in the Dps protein (His 25, His 37, Asp 41, Asp 52, and Glu 56). The maximum number of iron atoms bound by Dps (40.1 ± 3.1 per subunit) was also similar to those of other Dps family proteins (11, 43, 53).

Iron stimulates the generation of highly reactive oxygen, hydroxyl radicals, through the Fenton reaction, causing DNA damage (7, 23, 44). The strict regulation of assimilation and storage of iron in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells is believed to prevent free intracellular iron accumulation, protecting cells from iron toxicity (21, 28). In bacteria, there exist two types of iron storage proteins, heme-containing bacterioferritins and nonheme ferritins, both consisting of 24 identical or similar subunits. Ferritins have the ability to store iron in a nontoxic, bio-available form within a shell, which appears to protect the cell from the harmful effects of iron while making this essential element available when needed. The role of bacterioferritin remains unclear (1, 41).

In our previous report, a nonheme ferritin (Cft) has been identified in C. jejuni and shown to be important for growth under iron-restricted conditions (47). We investigated whether this iron-binding protein Dps, in growth under iron limitation, played a role similar to that of ferritin. The growth of the Dps-deficient mutant was similar to that of the parent strain under iron limitation (data not shown).

We found that Dps played an important role in the protection of C. jejuni against hydrogen peroxide stress. The dps mutant was significantly more sensitive to H2O2 than the parent and the cft mutant strains (Table 2). Dps possesses iron-binding ability, and pretreatment with the iron chelator Desferal reduced the sensitivity of the dps mutant to H2O2 (Fig. 4). Thus, in our experiments, a possible role of Dps to protect C. jejuni from iron-mediated hydrogen peroxide stress has been demonstrated in vivo. Yamamoto et al. (52) reported that Dpr, a S. mutans Dps homologue, which was induced by exposure of S. mutans to air and accumulated abundantly in S. mutans cells, bound iron, and its deficient mutant lost the ability to grow under air. They suggested that the existence of a high concentration of Dpr in S. mutans enabled intracellular free iron concentration to be kept low. They also showed that the ability of Dpr to inhibit the generation of iron-dependent hydroxyl radicals is much stronger than that of ferritin in vitro. Recently, in E. coli, Dps was shown to be an iron-binding and storage protein where Fe(II) oxidation was most effectively accomplished by H2O2 rather than by O2 as in ferritins, in a manner different from the Fenton reaction (56). It thus nullified the toxic combination of Fe(II) and H2O2 without hydroxyl radical production.

Taken together, we speculate that in C. jejuni, ferritin might mainly play a role in controlling cellular iron homeostasis by storing and releasing iron under iron-restricted conditions, whereas Dps might mainly contribute to protection against oxidative stress by sequestering cellular free iron to prevent the generation of hydroxyl radicals under hydrogen peroxide stress via the Fenton reaction.

In E. coli, the expression of many of the H2O2-inducible activities is regulated by the OxyR transcription factor, including dps, catalase (katG), and the two subunits of an alkyl hydroperoxide reductase (ahpCF) (reviewed in reference 39).

In C. jejuni, catalase (katA) and alkyl hydroperoxide reductase are controlled mainly by the Fur (Ferric uptake regulator) homologue PerR (peroxide stress regulator) and are repressed by iron (8, 45, 46). C. jejuni Dps was constitutively expressed during both exponential phase and stationary phase, and no further induction was observed when the cells were exposed to H2O2 or under iron-supplemented or iron-restricted growth conditions (Fig. 5). Survival assays also revealed that the survival of the dps mutant was compromised within a very short period of time during H2O2 challenge (Fig. 4). Therefore, it seems likely that microaerophilic C. jejuni might express this iron-binding protein constitutively to strictly control the level of iron and to minimize the toxicity of iron under hydrogen peroxide stress.

In conclusion, Dps plays an important role in survival under hydrogen peroxide stress by sequestering intracellular free iron. Further characterization of the dps mutant, e.g., by intracellular survival assays, will hopefully provide further understanding of the function of this iron-binding protein in pathogenesis.

Acknowledgments

We thank B. E. Uhlin for scientific discussion and critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank H. Nakayama, O. Shimokawa, K. Takeshige, and Y. Yamamoto for scientific discussion. We thank H. Aramaki, K. Iida, H. Kajiwara, M. Saito, and C. C. Sze for technical assistance.

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (2) 14370094 and (B) (1) 12490009 from the Ministry of Education, Science, Culture, and Sports of Japan, and the Swedish Foundation for International Cooperation in Research and Higher Education (STINT ref. no. 99/966). Sun Nyunt Wai was in part supported by a visiting scientist grant from the Wenner-Gren Foundations.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdul-Tehrani, H., A. J. Hudson, Y. S. Chang, A. R. Timms, C. Hawkins, J. M. Williams, P. M. Harrison, J. R. Guest, and S. C. Andrews. 1999. Ferritin mutants of Escherichia coli are iron deficient and growth impaired, and fur mutants are iron deficient. J. Bacteriol. 181:1415-1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allos, B. M. 1997. Association between Campylobacter infection and Guillain-Barré syndrome. J. Infect. Dis. 176(Suppl. 2):S125-S128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allos, B. M. 2001. Campylobacter jejuni infections: update on emerging issues and trends. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32:1201-1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Almiron, M., A. J. Link, D. Furlong, and R. Kolter. 1992. A novel DNA-binding protein with regulatory and protective roles in starved Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 6:2646-2654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ando, T., Q. Xu, M. Torres, K. Kusugami, D. A. Israel, and M. J. Blaser. 2000. Restriction-modification system differences in Helicobacter pylori are a barrier to interstrain plasmid transfer. Mol. Microbiol. 37:1052-1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antelmann, H., S. Engelmann, R. Schmid, A. Sorokin, A. Lapidus, and M. Hecker. 1997. Expression of a stress- and starvation-induced dps/pexB-homologous gene is controlled by the alternative sigma factor σB in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 179:7251-7256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aruoma, O. I., B. Halliwell, and M. Dizdaroglu. 1989. Iron ion-dependent modification of bases in DNA by the superoxide radical-generating system hypoxanthine/xanthine oxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 264:13024-13028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baillon, M. L., A. H. van Vliet, J. M. Ketley, C. Constantinidou, and C. W. Penn. 1999. An iron-regulated alkyl hydroperoxide reductase (AhpC) confers aerotolerance and oxidative stress resistance to the microaerophilic pathogen Campylobacter jejuni. J. Bacteriol. 181:4798-4804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bereswill, S., U. Waidner, S. Odenbreit, F. Lichte, F. Fassbinder, G. Bode, and M. Kist. 1998. Structural, functional and mutational analysis of the pfr gene encoding a ferritin from Helicobacter pylori. Microbiology 144:2505-2516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Black, R. E., M. M. Levine, T. P. Clements, and M. J. Blaser. 1988. Experimental Campylobacter jejuni infection in humans. J. Infect. Dis. 157:472-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bozzi, M., G. Mignogna, S. Stefanini, D. Barra, C. Longhi, P. Valenti, and E. Chiancone. 1997. A novel non-heme iron-binding ferritin related to the DNA-binding proteins of the Dps family in Listeria innocua. J. Biol. Chem. 272:3259-3265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Briat, J. F. 1992. Iron assimilation and storage in prokaryotes. J. Gen. Microbiol. 138:2475-2483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen, L., and J. D. Helmann. 1995. Bacillus subtilis MrgA is a Dps (PexB) homologue: evidence for metalloregulation of an oxidative-stress gene. Mol. Microbiol. 18:295-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chung, M. C. 1985. A specific iron stain for iron-binding proteins in polyacrylamide gels: application to transferrin and lactoferrin. Anal. Biochem. 148:498-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donahue, J. P., D. A. Israel, R. M. Peek, M. J. Blaser, and G. G. Miller. 2000. Overcoming the restriction barrier to plasmid transformation of Helicobacter pylori. Mol. Microbiol. 37:1066-1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evans, D. J., Jr., D. G. Evans, H. C. Lampert, and H. Nakano. 1995. Identification of four new prokaryotic bacterioferritins, from Helicobacter pylori, Anabaena variabilis, Bacillus subtilis and Treponema pallidum, by analysis of gene sequences. Gene 153:123-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodwin, C. S., J. A. Armstrong, T. Chilvers, M. Peters, M. D. Collins, L. Sly, W. McConnell, and W. E. S. Harper. 1989. Transfer of Campylobacter pylori and Campylobacter mustelae to Helicobacter gen. nov. as Helicobacter pylori comb. nov. and Helicobacter mustelae comb. nov., respectively. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 39:397-405. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grant, R. A., D. J. Filman, S. E. Finkel, R. Kolter, and J. M. Hogle. 1998. The crystal structure of Dps, a ferritin homolog that binds and protects DNA. Nat. Struct. Biol. 5:294-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Halliwell, B., and J. M. Gutteridge. 1992. Biologically relevant metal ion-dependent hydroxyl radical generation. An update. FEBS Lett. 307:108-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanahan, D. 1983. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J. Mol. Biol. 166:557-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harrison, P. M., and P. Arosio. 1996. The ferritins: molecular properties, iron storage function and cellular regulation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1275:161-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ilari, A., S. Stefanini, E. Chiancone, and D. Tsernoglou. 2000. The dodecameric ferritin from Listeria innocua contains a novel intersubunit iron-binding site. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7:38-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Imlay, J. A., S. M. Chin, and S. Linn. 1988. Toxic DNA damage by hydrogen peroxide through the Fenton reaction in vivo and in vitro. Science 240:640-642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnston, K. H., and J. B. Zabriskie. 1986. Purification and partial characterization of the nephritis strain-associated protein from Streptococcus pyogenes, group A. J. Exp. Med. 163:697-712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jung, D. H., and A. C. Parker. 1970. A semi-micromethod for the determination of serum iron and iron-binding capacity without deproteinization. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 54:813-817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ketley, J. M. 1997. Pathogenesis of enteric infection by Campylobacter. Microbiology 143:5-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keyer, K., A. S. Gort, and J. A. Imlay. 1995. Superoxide and the production of oxidative DNA damage. J. Bacteriol. 177:6782-6790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klausner, R. D., T. A. Rouault, and J. B. Harford. 1993. Regulating the fate of mRNA: the control of cellular iron metabolism. Cell 72:19-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martinez, A., and R. Kolter. 1997. Protection of DNA during oxidative stress by the nonspecific DNA-binding protein Dps. J. Bacteriol. 179:5188-5194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller, J. F., W. J. Dower, and L. S. Tompkins. 1988. High-voltage electroporation of bacteria: genetic transformation of Campylobacter jejuni with plasmid DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:856-860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller, R. A., and B. E. Britigan. 1997. Role of oxidants in microbial pathophysiology. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 10:1-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olczak, A. A., J. W. Olson, and R. J. Maier. 2002. Oxidative-stress resistance mutants of Helicobacter pylori. J. Bacteriol. 184:3186-3193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Papinutto, E., W. G. Dundon, N. Pitulis, R. Battistutta, C. Montecucco, and G. Zanotti. 2002. Structure of two iron-binding proteins from Bacillus anthracis. J. Biol. Chem. 277:15093-15098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pena, M. M., and G. S. Bullerjahn. 1995. The DpsA protein of Synechococcus sp. strain PCC7942 is a DNA-binding hemoprotein. Linkage of the Dps and bacterioferritin protein families. J. Biol. Chem. 270:22478-22482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Purdy, D., S. Cawthraw, J. H. Dickinson, D. G. Newell, and S. F. Park. 1999. Generation of a superoxide dismutase (SOD)-deficient mutant of Campylobacter coli: evidence for the significance of SOD in Campylobacter survival and colonization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:2540-2546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sambrook, J., and W. J. Russel. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N. Y.

- 38.Smith, P. K., R. I. Krohn, G. T. Hermanson, A. K. Mallia, F. H. Gartner, M. D. Provenzano, E. K. Fujimoto, N. M. Goeke, B. J. Olson, and D. C. Klenk. 1985. Measurement of protein using bicinchoninic acid. Anal. Biochem. 150:76-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Storz, G., and J. A. Imlay. 1999. Oxidative stress. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2:188-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Studier, F. W., A. H. Rosenberg, J. J. Dunn, and J. W. Dubendorff. 1990. Use of T7 RNA polymerase to direct expression of cloned genes. Methods Enzymol. 185:60-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Theil, E. C. 1987. Ferritin: structure, gene regulation, and cellular function in animals, plants, and microorganisms. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 56:289-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tonello, F., W. G. Dundon, B. Satin, M. Molinari, G. Tognon, G. Grandi, G. Del Giudice, R. Rappuoli, and C. Montecucco. 1999. The Helicobacter pylori neutrophil-activating protein is an iron- binding protein with dodecameric structure. Mol. Microbiol. 34:238-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Touati, D., M. Jacques, B. Tardat, L. Bouchard, and S. Despied. 1995. Lethal oxidative damage and mutagenesis are generated by iron in Δ fur mutants of Escherichia coli: protective role of superoxide dismutase. J. Bacteriol. 177:2305-2314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Vliet, A. H., M. L. Baillon, C. W. Penn, and J. M. Ketley. 1999. Campylobacter jejuni contains two fur homologs: characterization of iron-responsive regulation of peroxide stress defense genes by the PerR repressor. J. Bacteriol. 181:6371-6376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Vliet, A. H., K. G. Wooldridge, and J. M. Ketley. 1998. Iron-responsive gene regulation in a Campylobacter jejuni fur mutant. J. Bacteriol. 180:5291-5298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wai, S. N., K. Nakayama, K. Umene, T. Moriya, and K. Amako. 1996. Construction of a ferritin-deficient mutant of Campylobacter jejuni: contribution of ferritin to iron storage and protection against oxidative stress. Mol. Microbiol. 20:1127-1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wai, S. N., T. Takata, A. Takade, N. Hamasaki, and K. Amako. 1995. Purification and characterization of ferritin from Campylobacter jejuni. Arch. Microbiol. 164:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang, Y., and D. E. Taylor. 1990. Natural transformation in Campylobacter species. J. Bacteriol. 172:949-955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wassenaar, T. M., B. N. Fry, and B. A. van der Zeijst. 1993. Genetic manipulation of Campylobacter: evaluation of natural transformation and electro-transformation. Gene 132:131-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yamamoto, Y., M. Higuchi, L. B. Poole, and Y. Kamio. 2000. Identification of a new gene responsible for the oxygen tolerance in aerobic life of Streptococcus mutans. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 64:1106-1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yamamoto, Y., M. Higuchi, L. B. Poole, and Y. Kamio. 2000. Role of the dpr product in oxygen tolerance in Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 182:3740-3747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yamamoto, Y., L. B. Poole, R. R. Hantgan, and Y. Kamio. 2002. An iron-binding protein, Dpr, from Streptococcus mutans prevents iron-dependent hydroxyl radical formation in vitro. J. Bacteriol. 184:2931-2939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yanisch-Perron, C., J. Vieira, and J. Messing. 1985. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene 33:103-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yao, R., R. A. Alm, T. J. Trust, and P. Guerry. 1993. Construction of new Campylobacter cloning vectors and a new mutational cat cassette. Gene 130:127-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhao, G., P. Ceci, A. Ilari, L. Giangiacomo, T. M. Laue, E. Chiancone, and N. D. Chasteen. 2002. Iron and hydrogen peroxide detoxification properties of DNA-binding protein from starved cells. A ferritin-like DNA-binding protein of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 277:27689-27696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]