Abstract

Bacterial pathogens regulate virulence factor expression at both the level of transcription initiation and mRNA processing/turnover. Within Staphylococcus aureus, virulence factor transcript synthesis is regulated by a number of two-component regulatory systems, the DNA binding protein SarA, and the SarA family of homologues. However, little is known about the factors that modulate mRNA stability or influence transcript degradation within the organism. As our entree to characterizing these processes, S. aureus GeneChips were used to simultaneously determine the mRNA half-lives of all transcripts produced during log-phase growth. It was found that the majority of log-phase transcripts (90%) have a short half-life (<5 min), whereas others are more stable, suggesting that cis- and/or trans-acting factors influence S. aureus mRNA stability. In support of this, it was found that two virulence factor transcripts, cna and spa, were stabilized in a sarA-dependent manner. These results were validated by complementation and real-time PCR and suggest that SarA may regulate target gene expression in a previously unrecognized manner by posttranscriptionally modulating mRNA turnover. Additionally, it was found that S. aureus produces a set of stable RNA molecules with no predicted open reading frame. Based on the importance of the S. aureus agr RNA molecule, RNAIII, and small stable RNA molecules within other pathogens, it is possible that these RNA molecules influence biological processes within the organism.

Staphylococcus aureus is a gram-positive pathogen that is capable of causing a number of infections, which range in severity from minor skin infections to life-threatening endocarditis and osteomyelitis. Although the organism is part of the normal human flora, it can cause infection when there is a break in the skin or mucous membrane that grants it access to the surrounding tissues (17, 39). S. aureus owes its ability to subsequently colonize host tissue and disseminate to other sites to the production of an array of virulence factors. Generally, these factors include accessory cytoplasmic, surface, and secreted components, which are coordinately regulated at the transcriptional level in response to endogenous and environmental cues, i.e., cell density, pH, and subinhibitory concentrations of antibiotics (9, 36, 46, 61). Virulence factor regulation is modulated by at least seven two-component regulatory systems (ArlRS [26], SaeRS [47, 55], AgrAC [35], SrrAB [62], LytRS [14], YycFG [44], and VraRS [37]), the DNA-binding protein SarA (18), and the SarA family of homologues (SarS [19, 57], SarR [40], SarU [42], SarT [51], SarV [43], MgrA [30, 31], and TcaR [45]).

The S. aureus sarA locus includes a 1.2-kb DNA fragment that produces three overlapping transcripts (sarA, sarB, and sarC), each of which shares a termination site and encodes SarA protein (5). In the laboratory setting, protein levels remain constant throughout growth phases (12). Yet, sarA and sarB transcripts are preferentially transcribed during log-phase growth. At higher cell densities, sarA and sarB transcript titers decrease, whereas sarC mRNA levels increase (12). sarC transcription is also driven by the alternative sigma factor σB (41). The significance of each transcriptional unit's production has not been studied in detail.

SarA is a pleiotropic regulator that negatively effects the protein production of several virulence factors, including protein A (spa), collagen-binding protein (cna), and serine proteinase (sspA) (5, 12, 34). Northern blotting and microarray studies have indicated that SarA's regulatory effects are, at least in part, at the transcriptional level. Electrophoretic gel-mobility shift assays and DNA footprinting have revealed that SarA is capable of binding to a 26-bp and/or 7-bp sequence within the promoter region of these target genes, suggesting that SarA acts as a transcription factor (20, 56). Nonetheless, it remains to be seen whether either of these putative SarA binding sites has any biological relevance. For instance, the 26-bp site cannot be found within 150 bp of the predicted translational start site of ∼70% of the genes whose transcript titers were found to be modulated in a sarA-dependent manner by microarray analysis (24). Likewise, the S. aureus strain N315 sequence contains >2,500 7-bp (ATTTTAT) putative SarA binding sites within its genome (P. M. Dunman and E. Murphy, unpublished data). It is difficult to imagine that a bona fide transcription factor binds this number of sites. Despite the presence of both putative SarA binding sites (7 bp and 26 bp) within the spa promoter region, Arvidson and Tegmark have indicated that protein A production is indirectly regulated by SarA, suggesting that it may regulate target gene expression in a previously unrecognized manner (2). The crystal structure of a SarA-DNA complex has been solved and indicates that SarA mediates DNA supercoiling. Based on this, it was suggested that SarA may act like the Escherichia coli proteins Fis, integration host factor, H-NS, and HU and function as a global DNA architectural protein that influences DNA superhelicity and transcription rather than a bona fide transcription factor (52).

Indeed, E. coli DNA architectural proteins (also known as histone-like proteins) share several similarities with SarA. They are relatively small (∼9 kDa) and abundant proteins, some of which also bind AT-rich regions of the chromosome (59). Histone-like proteins also act as pleiotropic regulatory molecules. Their regulatory functions differ from prototypical transcription factors in that they tend to globally regulate gene expression by binding to and altering the topology of gene promoter regions, which subsequently influences transcript synthesis (3, 25, 58). Histone-like proteins also posttranscriptionally modulate gene expression by binding directly to mRNA molecules and influencing transcript stability and translation (4, 13, 22). Based on the similarities between SarA and the histone-like proteins, we hypothesized that SarA may modulate gene expression on the level of both initiation of transcript synthesis and mRNA turnover.

Most prokaryotic studies of mRNA processing and turnover are limited to a few mRNA species within E. coli and, to a lesser extent, Bacillus subtilis. Those studies have indicated that bacterial mRNAs are generally unstable and undergo complex degradation processes that differ between E. coli and B. subtilis (reviewed in reference 21). As our entree to defining the molecular mechanism(s) of S. aureus mRNA processing and determining whether SarA influences the stability of target transcripts, we used Affymetrix S. aureus GeneChips to define the mRNA turnover properties of both wild-type and sarA mutant cells. Results indicate that the majority (90%) of all wild-type log-phase transcripts have an mRNA half-life of less than 5 min, whereas other transcripts are more stable, suggesting that cis- and/or trans-acting elements modulate mRNA turnover within S. aureus. In support of this, we found that two virulence factor transcripts, spa and cna, were stabilized in a sarA-dependent manner. Correlations between sarA's mRNA-stabilizing effects and protein production indicate that sarA may posttranscriptionally regulate virulence factor production. It was also found that S. aureus produces small stable mRNA molecules, with no obvious open reading frame.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. UAMS-1 is a well-characterized methicillin-susceptible clinical osteomyelitis isolate.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

Sampling, RNA isolation, and GeneChip analysis.

Overnight cultures of S. aureus were diluted 1:100 in 250 ml fresh brain heart infusion (BHI) medium and were incubated at 37°C at 200 rpm with a flask-to-medium volume ratio of 6:1. Once cultures reached mid-log phase (optical density at 600 nm = 0.3 to 0.4), rifampin (200 μg ml−1; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was added to arrest transcription; Lee and Birkbeck have previously shown that 200 μg ml−1 rifampin rapidly and completely blocks S. aureus mRNA synthesis (38). Twenty-one milliliters of cells was removed at 0, 5, 15, 30, and 60 min after rifampin treatment. Aliquots were immediately processed for RNA isolation and for monitoring both cell viability and rifampin resistance. More specifically, 20 ml of each aliquot was added to 20 ml ice-cold acetone-ethanol (1:1) and stored at −80°C overnight; 10−1 and 10−5 dilutions of the remaining 1 ml were plated on BHI-rifampin (200 μg ml−1) and BHI agar, respectively. Plates were incubated overnight at 37°C, and viable numbers of CFU ml−1 were calculated to ensure that cell proliferation was halted by the addition of rifampin, suggesting that transcription was arrested. If rifampin-resistant colonies were detected, the experiment was discarded and repeated. For RNA isolation, −80°C suspensions were thawed on ice and centrifuged at 5,000 × g at 4°C for 10 min. The supernatant was removed, and the cell pellet was resuspended in 1 ml ice-cold TE buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) and transferred to a prechilled lysing matrix B tube (Q-BIOgene, Irvine, CA). Cells were lysed by shaking in an FP120 shaker (Q-BIOgene) two times at a setting of 4.5 for 20 s. Suspensions were then centrifuged at 13,000 × g at 4°C for 10 min, and the supernatant was used for RNA isolation with an RNeasy Mini column, according to the manufacturer's recommendations for on-the-column DNase treatment and RNA purification (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). The RNA concentration was determined by spectrophotometry (optical density at 260 nm of 1 = 40 μg RNA ml−1). Any residual DNA contamination was then removed by treatment with 1 U DNase I (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) 10 μg RNA−1 at 37°C for 30 min. RNA was then repurified with an RNeasy Mini column, according to the manufacturer's recommendations for RNA clean-up (QIAGEN), and subsequently quantitated by spectrophotometry. In preliminary studies, S. aureus rRNA was stable at 60 min post-transcriptional arrest (data not shown). Thus, the integrity of rRNA within each RNA preparation was analyzed by electrophoresis in a 1.2% agarose-0.66 M formaldehyde gel to confirm that RNA preparations were not subjected to contaminating RNase activity during handling. RNA was then reverse transcribed, and cDNA was fragmented, 3′ biotinylated, mixed with exogenous labeled “spike-in” transcripts, and hybridized to S. aureus GeneChips by following the manufacturer's recommendations for antisense prokaryotic arrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). The S. aureus GeneChips (Saur2a) used in this study are second-generation custom-made Affymetrix arrays representing consensus and unique sequences from S. aureus strains MRSA252, MSSA476, NCTC 8325, COL, N315, and Mu50 as well as unique GenBank entries and N315 intergenic regions greater than 50 nucleotides (nt) in length (23). GeneChips were washed, stained, and scanned, as previously described (8). Each strain was analyzed at least twice. GeneChip signal intensity values for each qualifier at each time point were then averaged and normalized to spike-in signals using GeneSpring 6.2 software (Silicon Genetics, Redwood City, CA). The half-life of each transcript was calculated as the time point at which the time zero (T0) signal decreased by a factor of 2, as previously described (53).

Real-time PCR.

Real-time PCR primers are shown in Table 2. For standard real-time PCRs 25 ng of RNA was reverse transcribed, amplified, and measured using a LightCycler RNA Master SYBR green I kit (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN), according to the manufacturer's recommendations. As an internal control, 25 pg of RNA was used to quantitate rRNA. Transcript concentrations were calculated using LightCycler software and the LightCycler control cytokine RNA (Roche Applied Science) titration kit as a standard and were then normalized to 16S rRNA abundance. Real-time PCR-determined relative (n-fold) degradation of the indicated mRNA species was measured as the difference between the transcript titer at T0 and the time point indicated, following the addition of rifampin.

TABLE 2.

Sequences of oligonucleotides used in PCR, Lightcycler, or Northern blotting reactions in this study

| Primer or probe | Oligonucleotide sequence (5′→3′) |

|---|---|

| Lightcycler | |

| spa-F | CAGATAACAAATTAGCTGATAAAAACAT |

| spa-R | CTAAGGCTAATGATAATCCACCAAATAC |

| cna-F | AACGAACAAGTATACACCAGGAGAG |

| cna-R | TTTGCTTTTTCATCTAATCCTGTC |

| 16SrRNA-F | ACACAGTCTGAGATGATTGTAGTGTTC |

| 16SrRNA-R | GCTTTCACATCAGACTTAAAAA |

| SA1278-F | ACACAGTCTGAGATGATTGTAGTGTTC |

| SA1278-R | ATCGAAAGACTTAGGATATTTCATTGC |

| gyrA-F | CTGAGCGTAATGGTAATGTTGTATG |

| gyrA-R | TGCATCTTCTTTTACTTTAGCAACC |

| dnaA-F | CCAAAAGAAACAACAAAACCTTCTA |

| dnaA-R | AAACCAACCCCTCCATAGATAAATA |

| hup-F | CTGGTTCAGCAGTAGATGCTGTATT |

| hup-R | ATCTTTTAATGCTTTACCAGCTTTG |

| purH-F | ATCAAGAAGTATTGACGCGATTAAG |

| purH-R | GATTGTTGTGGATTTTCTCCATATC |

| PCR | |

| spa-F | CATACAGGGGGTATTAATTTGAAAA |

| spa-R | AGTAGAAAGTGTTGAGGCGTTTCAG |

| 16SrRNA-F | TTTTATGGAGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTC |

| 16SrRNA-R | ATATCCTTAGAAAGGAGGTGATCCAG |

| Northern blotting | |

| WAN014GIY | CCTGATACACATCTTTCTACGTGTG |

| cna-F | AACGAACAAGTATACACCAGGAGAG |

Northern blotting.

Ten micrograms of purified total bacterial RNA (as indicated in text) was run in a 1% (wt/vol) formaldehyde-containing agarose gel at 75 V for 1.5 h. RNA samples were transferred to nylon Hybond-N membranes (Amersham Biosciences) by overnight capillary transfer in 20× SSC (0.3 M Na3 citrate, 3.0 M NaCl; pH 7.0) (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) and were immobilized by UV cross-linking. Oligonucleotide probes (Table 2) for cna and GeneChip qualifier WAN014GIY transcripts were 3′ digoxigenin labeled using digoxigenin oligonucleotide 3′-end-labeling kits (Roche Applied Science) according to the manufacturer's recommendations for labeling, determining labeling efficiency, hybridization, and detection steps for Northern blot analysis.

RESULTS

Log-phase mRNA half-lives.

S. aureus strain UAMS-1 is a well-characterized, highly virulent clinical isolate, and its genetic composition has recently been determined (7, 8, 10, 11, 16). The mRNA half-lives of all transcripts produced during log-phase UAMS-1 and isogenic sarA mutant cell growth were measured using S. aureus Affymetrix GeneChips (Saur2a). Briefly, each strain was grown to mid-log phase in nutrient-rich media and was treated with rifampin to arrest transcription, as previously described (38). Aliquots were removed at 0, 5, 15, 30, and 60 min post-transcriptional arrest and monitored for rifampin resistance. For experiments in which no resistance was detected, total bacterial RNA was labeled and hybridized to Affymetrix S. aureus GeneChips.

The GeneChip signal intensity values for all log-phase transcripts at each sampled time point are shown in Fig. 1. All experiments were repeated at least twice. A comparison of T0 samples from two independent experiments confirmed that the methodology used was reproducible; less than 0.3% of all transcripts demonstrated more than a twofold difference in titer (Fig. 1A). Similar levels of reproducibility were observed when comparing all other sampling times among independent experiments (<0.5% variability; data not shown). Results shown in Fig. 1B to E indicate that transcript signals decrease in a time-dependent manner, confirming that the amount of rifampin used was appropriate to rapidly and completely arrest de novo transcript synthesis. Results also suggest that although most transcripts degrade rapidly, several mRNA molecules appear to be less susceptible to degradation. To study transcript degradation rates in more detail, the mRNA half-life of each transcript was determined as the time point at which the amount of signal detected at time point zero decreased by a factor of two and are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. This method of measuring mRNA half-lives has been shown to be extremely accurate by Selinger and colleagues (53).

FIG. 1.

Degradation profile of S. aureus log-phase transcripts. The mRNA signal intensity values for each transcript represented on the GeneChip are plotted (+) at 0 min (T0; x axis) and at various time points after rifampin treatment (y axis). All measurements are averages of the results from at least two independent experiments. The gray dashed line indicates the level of sensitivity of the system. (A) All GeneChip transcript signals are plotted for T0 samples from two independent experiments, illustrating the reproducibility of the measurements taken. The average transcript signals for each mRNA molecule at T0 are plotted in comparison to the amount of signal detected at 5 min (B), 15 min (C), 30 min (D), and 60 min (E) after rifampin treatment.

We have previously found that UAMS-1 DNA hybridizes to 2,775 S. aureus GeneChip qualifiers, representing known or predicted S. aureus open reading frames (ORFs), as well as intergenic regions greater than 50 bp in length (16). A total of 644 (23.2%) of these 2,775 qualifiers demonstrated background levels of signal intensity prior to the addition of rifampin, suggesting that they were not transcribed at an appreciable level during log-phase growth. Thus, their mRNA half-lives could not be measured, and they are not included in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Many of these genes code for factors that are known to be preferentially expressed during late-log-phase growth, such as all of the members of the intercellular adhesion (ica), gamma hemolysin (hlg), and serine protease (spl) operons (24). A total of 1,910 (89.6%) of the 2,131 measurable log-phase transcripts had an mRNA half-life of less than 5 min. The mRNA half-lives of the remaining 221 transcripts were determined to be as follows: 173 (8.1%) between 5 and 15 min; 29 (1.3%) between 15 and 30 min; 3 (0.1%) between 30 and 60 min; and 16 (0.7%) after 60 min. These results suggest that the stability of S. aureus transcripts can be influenced by cis-acting elements and/or by trans-acting factors. In large part, the degradation rates of genes within an operon coincided with one another.

Transcripts with intermediate levels of stability (half-lives of >5 min but <60 min) included members of operons that could be associated with biological functions. These transcripts included the ATP synthase operon (atpA, atpC, atpD, atpE, atpF, atpG, and atpH), heat shock proteins (groES and groEL), members of the urease complex (ureAB, ureC, ureF, and ureG), and 33 genes coding for members of the translation apparatus (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The mRNA half-lives of several transcripts with either short (gyrA and purH) or long (hup and N315 SA1278) half-lives were confirmed by real-time PCR, indicating that the methodology used was appropriate to measure mRNA turnover (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Comparison of GeneChip-determined mRNA half-lives and real-time PCR-determined relative degradation

| Genea | Half-life (min)b | Fold decrease in mRNA titer at time (min)c:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 15 | 30 | 60 | ||

| gyrA | ≤5 | 9.8 (±0.8) | ND | ND | ND |

| purH | ≤5 | 15.3 (±6.5) | ND | ND | ND |

| hup | 30-60 | 1.2 (±0.5) | 1.8 (±0.3) | 7.8 (±2.1) | ND |

| SA1278 | >60 | 1.4 (±0.2) | 1.1 (±0.3) | 1.3 (±0.2) | 1.3 (±0.2) |

S. aureus strain N315 common gene name or locus.

GeneChip-determined mRNA half-life.

Real-time PCR-determined relative decrease in mRNA titer following 5, 15, 30, and 60 min of transcriptional arrest. ND, not determined.

Stable RNA molecules.

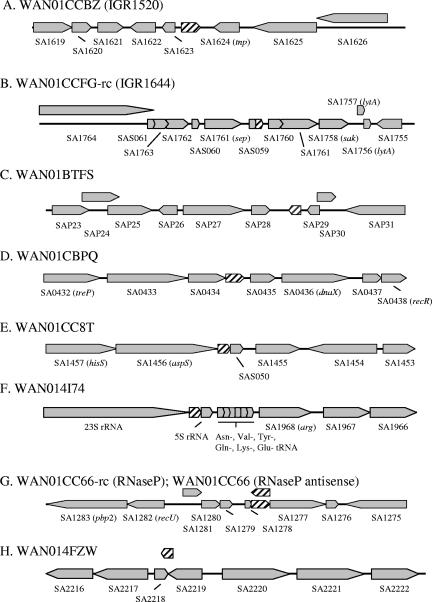

Sixteen RNA species did not demonstrate any appreciable degradation following 60 min of transcriptional arrest (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Three of these transcripts are expected to encode proteins with no known function. The remaining 13 transcripts do not contain an obvious open reading frame. Among these are five well-defined RNA molecules, including a serine tRNA, 16S and 23S rRNAs, tmRNA (15), and the RNA component of RNase P (54). Indeed, 16S and 23S rRNAs are generally regarded as stable RNA molecules. tmRNA (also known as SsrA) is an RNA molecule involved in protein tagging and rescuing stalled ribosomes that has been defined as a stable RNA species within other organisms (15). Northern blotting analysis demonstrated that the S. aureus tmRNA/ssrA locus produces at least 3 RNA species during log-phase growth, each of which appears to be stable for at least 2 h post-transcriptional arrest (Fig. 2), further confirming our GeneChip results. Eight transcripts that map to short (75 to 360 nt) N315 intergenic regions, but with no defined function, were also identified (Fig. 3). Two of these molecules (measured by GeneChip qualifiers WAN01CCBZ and WAN01CCFG-rc) were recently characterized to be transcripts without an obvious putative ORF sequence by Pichon and Felden, although their half-lives were not determined in that study (50). Based on the surrounding genomic content and directionality of transcript synthesis, it is likely that some stable RNA molecules are cotranscribed as part of an operon, whereas others are more likely to behave as antisense RNA molecules. For instance, the RNA component of RNase P holoenzyme, a protein/RNA complex that matures tRNA molecules, was measured by GeneChip qualifier WAN01CC66-rc and determined to be stable. Interestingly, a transcript mapping to the opposite strand was also determined to be stable (Fig. 3) (measured by GeneChip qualifier WAN01CC66). One can imagine a scenario whereby the latter RNA molecule may behave as an antisense molecule and regulate RNase P function. Indeed, the importance of the S. aureus agr-encoded RNAIII molecule (48) and small stable RNAs within other pathogens (33) makes it likely that many of the stable transcripts identified here may play an important role(s) in S. aureus biological processes.

FIG. 2.

Transcript degradation profile of small stable RNA molecules. Northern blotting results of small stable RNA molecules at 0, 60, and 120 min following transcriptional arrest (shown across top). M, molecular size markers.

FIG. 3.

Chromosomal composition adjacent to UAMS-1 log-phase stable RNA transcripts. Shown is the S. aureus strain N315 chromosomal map position of each small stable UAMS-1 RNA locus. The GeneChip qualifier name and corresponding transcript name, if known, are given in parentheses. IGR1520 and IGR1624 correspond to transcripts and corresponding nomenclature previously described by Pichon and Felden (50). Orientations of ORFs (gray arrows) and stable transcript coding regions (striped arrows) are indicated.

sarA influences cna and spa transcript stability.

Because SarA is an abundant protein with promiscuous binding characteristics that can alter DNA topology, we hypothesized that the protein may, in part, act as a DNA-structuring protein. Indeed, the Escherichia coli histone-like protein integration host factor is an abundant DNA-binding protein which, like SarA, binds to AT-rich regions of the chromosome (59). Moreover, histone-like proteins, such as HU and H-NS, can bind to mRNA molecules in a manner that alters their stability and, in doing so, leads to the posttranscriptional regulation of target genes (4, 13, 22). Accordingly, the mRNA stability of log-phase transcripts produced within UAMS-1 (sarA) cells were determined and are included in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

In large part, the mRNA half-lives of transcripts produced in sarA cells matched those of wild-type cells, demonstrating the reproducibility of the GeneChip-based measurements. However, 138 mRNA molecules, including collagen-binding protein (cna) and protein A (spa) virulence factor transcripts, were found to have longer half-lives in wild-type than in sarA mutant cells, suggesting that they are stabilized in a sarA-dependent manner (Table 4). Nearly the complete set of UAMS-1 transcripts with intermediate level stability was more rapidly degraded in the sarA mutant background. Conversely, seven transcripts were determined to be destabilized in a sarA-dependent manner and are highlighted in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Because SarA has been shown to influence Spa and Cna production, we focused on characterizing this phenomenon in more detail.

TABLE 4.

Log-phase transcripts with differential degradation properties within UAMS-1 and isogenic sarA mutant cells

| Qualifiera | Common | Half-life (min) ofb:

|

Locusc | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WTe | sarA mutants | ||||

| Amino acid transport and metabolism | |||||

| WAN014HF5_at | gcvH | 15 | 5 | SA0760 | Glycine cleavage system protein H |

| WAN014I0A_at | glyA | 15 | 5 | SA1915 | Serine hydroxymethyl transferase |

| WAN014G7C_at | ureAB | 15 | 5 | SA2083 | Urease beta subunit |

| WAN014G7E_at | ureC | 15 | 5 | SA2084 | Urease alpha subunit |

| Carbohydrate transport and metabolism | |||||

| WAN014HDZ_at | eno | 15 | 5 | SA0731 | Enolase |

| WAN014I16_at | fba | 15 | 5 | SA1927 | Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase |

| WAN014GEN_at | fda | 15 | 5 | SA2399 | Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase homolog |

| WAN014HDR_at | gap | 15 | 5 | SA0727 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| WAN014HKV_at | pgi | 15 | 5 | SA0823 | Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase A |

| WAN014HDT_at | pgk | 15 | 5 | SA0728 | Phosphoglycerate kinase |

| WAN014HDX_at | pgm | 15 | 5 | SA0730 | 2, 3-Diphosphoglycerate-independent phosphoglycerate mutase |

| WAN014HSG_at | ptsH | 15 | 5 | SA0934 | Phophocarrier protein HPR |

| WAN014HDV_at | tpiA | 15 | 5 | SA0729 | Triosephosphate isomerase |

| WAN014H3R_at | 15 | 5 | SA0528 | Similar to hexulose-6-phosphate synthase | |

| WAN014G6N_at | 15 | 5 | SA2053 | Glucose uptake protein homolog | |

| Energy production and conversion | |||||

| WAN014HZV_at | atpA | 15 | 5 | SA1907 | ATP synthase alpha chain |

| WAN014HZJ_at | atpC | 15 | 5 | SA1904 | FoF1-ATP synthase epsilon subunit |

| WAN014HZO_at | atpD | 15 | 5 | SA1905 | ATP synthase beta chain |

| WAN014I01_at | atpE | 15 | 5 | SA1910 | ATP synthase C chain |

| WAN014HZZ_at | atpF | 15 | 5 | SA1909 | ATP synthase B chain |

| WAN014HZQ_at | atpG | 15 | 5 | SA1906 | ATP synthase gamma chain |

| WAN014HZX_at | atpH | 15 | 5 | SA1908 | ATP synthase delta chain |

| WAN014HTB_at | pdhA | 15 | 5 | MW0976 | Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex |

| WAN014HTC_at | pdhB | 15 | 5 | SA0944 | Pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component beta subunit |

| WAN014HTE_at | pdhC | 15 | 5 | SA0945 | Dihydrolipoamide acetyltransferase |

| WAN014HTG_at | pdhD | 15 | 5 | SA0946 | Dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase |

| WAN014GTJ_at | qoxA | 30 | 5 | SA0913 | Similar to quinol oxidase polypeptide II QoxA |

| WAN014GTH_at | qoxB | 30 | 5 | SA0912 | Quinol oxidase polypeptide I |

| WAN014GTE_at | qoxC | 15 | 5 | SA0911 | Quinol oxidase polypeptide III |

| WAN014GVS_at | 15 | 5 | SA0367 | Similar to nitro/flavin reductase | |

| WAN014GTD_at | 15 | 5 | SA0910 | Similar to quinol oxidase polypeptide IV QoxD | |

| WAN014G5B_at | 15 | 5 | SA2311 | Similar to NAD(P)H-flavin oxidoreductase | |

| General transport | |||||

| WAN014I5X_at | adk | 15 | 5 | SA2027 | Adenylate kinase |

| WAN014GDJ_at | copP | 15 | 5 | SA2345 | Similar to mercuric ion-binding protein |

| WAN014GTL_at | folD | 30 | 5 | SA0915 | FolD bifunctional protein |

| WAN014I1K_at | pyn | 15 | 5 | SA1938 | Pyrimidine nucleoside phosphorylase |

| WAN014I5Z_at | secY | 15 | 5 | SA2028 | Preprotein translocase SecY subunit |

| WAN014H6Q_at | sodA | 15 | 5 | SA1382 | Superoxide dismutase SodA |

| WAN014I08_at | upp | 15 | 5 | SA1914 | Uracil phosphoribosyl transferase |

| WAN014H1C_at | 15 | 5 | SA0477 | Conserved hypothetical protein | |

| WAN014H1E_at | 15 | 5 | SA0478 | Conserved hypothetical protein | |

| WAN014HF3_at | 15 | 5 | SA0759 | Similar to arsenate reductase | |

| Miscellaneous | |||||

| WAN014I20_at | acpP | 15 | 5 | SA1075 | Acyl carrier protein |

| WAN01BPWU_x_at | cspD | 15 | 5 | SA1234 | Major cold shock protein CspA |

| WAN014GCU_at | ddh | 15 | 5 | SA2312 | d-Specific d-2-hydroxyacid dehydrogenase |

| WAN014GWS_at | dmpl | 15 | 5 | SAS044 | 4-Oxalocrotonate tautomerase |

| WAN014H1M_at | hup | 60 | 5 | SA1305 | DNA-binding protein II (HB) |

| WAN014I5M_at | rpoA | 15 | 5 | SA2023 | DNA-directed RNA polymerase alpha chain |

| WAN014GVD_at | ssb | 15 | 5 | SA0353 | Single-stranded DNA-binding protein |

| WAN014I06_at | wecB | 15 | 5 | SA1913 | UDP-GlcNAc 2-epimerase |

| WAN014H7P_at | 15 | 5 | SA0182 | Similar to indole-3-pyruvate decarboxylase | |

| WAN014H3T_at | 15 | 5 | SA0529 | Conserved hypothetical protein | |

| WAN014FY9_at | 30 | 5 | SA1528 | Conserved hypothetical protein | |

| WAN014GJ0_at | 15 | 5 | tRNA-Ser | ||

| WAN014GJ6_at | 15 | 5 | tRNA-Gly | ||

| WAN014GIY_at | Stable | 5 | Unknown RNA | ||

| Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones | |||||

| WAN014GAE_at | ahpC | 15 | 5 | SA0366 | Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase subunit C |

| WAN014G9N_at | ahpF | 15 | 5 | SA0365 | Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase subunit F |

| WAN014HVE_at | groEL | 15 | 5 | SA1836 | GroEL protein |

| WAN014HVI_at | groES | 15 | 5 | SA1837 | GroES protein |

| WAN014G7I_at | ureF | 15 | 5 | SA2086 | Urease accessory protein UreF |

| WAN014G7K_at | ureG | 15 | 5 | SA2087 | Urease accessory protein UreG |

| WAN014H7X_at | 15 | 5 | SA1403 | Conserved hypothetical protein | |

| Translation | |||||

| WAN014H5H_at | efp | 15 | 5 | SA1359 | Translation elongation factor EF-P |

| WAN014H2U_at | fusA | 15 | 5 | SA0505 | Translational elongation factor G |

| WAN014I5V_at | infA | 15 | 5 | SA2026 | Translation initiation factor IF-1 |

| WAN014H2C_at | rplA | 15 | 5 | SA0496 | 50S ribosomal protein L1 |

| WAN014I6G_at | rplE | 15 | 5 | SA2035 | 50S ribosomal protein L5 |

| WAN014I69_at | rplF | 15 | 5 | SA2033 | 50S ribosomal protein L6 |

| WAN014H29_at | rplK | 15 | 5 | SA0495 | 50S ribosomal protein L11 |

| WAN014I6K_at | rplN | 15 | 5 | SA2037 | 50S ribosomal protein L14 |

| WAN014I61_at | rplO | 15 | 5 | SA2029 | 50S ribosomal protein L15 |

| WAN014I6S_at | rplP | 15 | 5 | SA2040 | 50S ribosomal protein L16 |

| WAN014I5K_at | rplQ | 15 | 5 | SA2022 | 50S ribosomal protein L17 |

| WAN014I67_at | rplR | 15 | 5 | SA2032 | 50S ribosomal protein L18 |

| WAN014I2L_at | rplS | 15 | 5 | SA1084 | 50S ribosomal protein L19 |

| WAN014I6I_at | rplX | 15 | 5 | SA2036 | 50S ribosomal protein L24 |

| WAN014A7W-5_at | rplY | 15 | 5 | SA0459 | 50S ribosomal protein L25 |

| WAN014GVM_at | rpmB | 15 | 5 | SA1067 | 50S ribosomal protein L28 |

| WAN014I6O_at | rpmC | 15 | 5 | SA2039 | 50S ribosomal protein L29 |

| WAN014I63_at | rpmD | 15 | 5 | SA2030 | 50S ribosomal protein L30 |

| WAN014FT7_at | rpmGd | 30 | 5 | SAS042 | 50S ribosomal protein L33 |

| WAN014H6M_at | rpmGd | 15 | 5 | SAS047 | 50S ribosomal protein L33 |

| WAN014H1V_at | rpsA | 15 | 5 | SA1308 | 30S ribosomal protein S1 |

| WAN014I65_at | rpsE | 15 | 5 | SA2031 | 30S ribosomal protein S5 |

| WAN014A7X-3_at | rpsF | 15 | 5 | SA0352 | 30S ribosomal protein S6 |

| WAN014A7X-5_at | rpsF | 15 | 5 | SA0352 | 30S ribosomal protein S6 |

| WAN014H2S_at | rpsG | 15 | 5 | SA0504 | 30S ribosomal protein S7 |

| WAN014I6B_at | rpsH | 15 | 5 | SA2034 | 30S ribosomal protein S8 |

| WAN014I5O_at | rpsK | 15 | 5 | SA2024 | 30S ribosomal protein S11 |

| WAN014H2Q_at | rpsL | 15 | 5 | SA0503 | 30S ribosomal protein S12 |

| WAN014I5Q_at | rpsM | 15 | 5 | SA2025 | 30S ribosomal protein S13 |

| WAN014I6D_at | rpsN | 15 | 5 | SAS079 | 30S ribosomal protein S14 |

| WAN014I6L_at | rpsQ | 15 | 5 | SA2038 | 30S ribosomal protein S17 |

| WAN014FXU_at | rpsT | 15 | 5 | SA1414 | 30S ribosomal protein S20 |

| WAN014A7V-3_at | tufd | 15 | 5 | SA0506 | Translational elongation factor TU |

| WAN014A7V-5_at | tufd | 30 | 5 | SA0506 | Translational elongation factor TU |

| WAN014A7V-M_at | tufd | 30 | 5 | SA0506 | Translational elongation factor TU |

| WAN014H2O_at | 15 | 5 | SA0502 | Similar to ribosomal protein | |

| Unknown | |||||

| WAN014HTM_at | ccoS | 15 | 5 | SAS056 | Hypothetical protein |

| WAN014HAL_at | csbD | 15 | 5 | SA1452 | σB-controlled gene product |

| WAN014G0U_at | hit | 15 | 5 | SA1656 | Hit-like protein |

| WAN014GSG_at | 15 | 5 | MW0922 | Hypothetical protein | |

| WAN014G09_at | 30 | 5 | MWP025 | Hypothetical protein | |

| WAN014HY6_at | 15 | 5 | SA0269 | Hypothetical protein | |

| WAN014GN8_at | 60 | 5 | SA0271 | Conserved hypothetical protein | |

| WAN014GPI_at | 15 | 5 | SA0295 | Similar to outer membrane protein precursor | |

| WAN014GVL_at | 15 | 5 | SA0359 | Conserved hypothetical protein | |

| WAN014H31_at | 15 | 5 | SA0509 | Conserved hypothetical protein | |

| WAN014IV8_at | 15 | 5 | SA0889 | Hypothetical protein | |

| WAN014GNH_at | Stable | 15 | SA1278 | Hypothetical protein | |

| WAN014H3P_at | 15 | 5 | SA1345 | Conserved hypothetical protein | |

| WAN014H3N_at | 15 | 5 | SA1344 | Conserved hypothetical protein | |

| WAN014H7T_at | 15 | 5 | SA1401 | Conserved hypothetical protein | |

| WAN014H7V_at | 15 | 5 | SA1402 | Conserved hypothetical protein | |

| WAN014HGB_x_at | 15 | 5 | SA1559 | Similar to smooth muscle caldesmon | |

| WAN014G2Y_at | 15 | 5 | SA1743 | Hypothetical protein | |

| WAN014GKY_at | 15 | 5 | SA1754 | Hypothetical protein (bacteriophage phiN315) | |

| WAN014HUU_at | 30 | 5 | SA1768 | Hypothetical protein (bacteriophage phiN315) | |

| WAN014I4W_at | 30 | 5 | SA1770 | Hypothetical protein (bacteriophage phiN315) | |

| WAN014HUY_at | 30 | 5 | SA1771 | Hypothetical protein (bacteriophage phiN315) | |

| WAN014HV0_at | 30 | 5 | SA1774 | Hypothetical protein (bacteriophage phiN315) | |

| WAN014I0C_at | 15 | 5 | SA1916 | Conserved hypothetical protein | |

| WAN014I3J_at | 15 | 5 | SA1985 | Hypothetical protein | |

| WAN014G6J_at | 15 | 5 | SA2049 | Hypothetical protein | |

| WAN014GD4_at | Stable | 5 | SA2331 | Hypothetical protein | |

| WAN014GED_at | 15 | 5 | SA2378 | Conserved hypothetical protein | |

| WAN014HSP_at | 30 | 5 | SAR0694 | Hypothetical protein | |

| WAN014IOE_at | 15 | 5 | SAR2779 | Putative N-acetyltransferase | |

| WAN014IVJ_at | Stable | 5 | SAS059 | Hypothetical protein (bacteriophage phiN315) | |

| WAN014IOC_at | 15 | 5 | SAV2383 | Hypothetical protein SAV2383 | |

| WAN014FZW_at | Stable | 5 | Antisense | ||

| Virulence factors | |||||

| WAN014HM2_at | cna | 15 | 5 | MW2612 | Collagen adhesin protein |

| WAN014IPY_at | fib | 15 | 5 | SAR1130 | Fibrinogen-binding protein precursor |

| WAN014ITO_s_at | spa | 30 | 5 | SA0107 | Immunoglobulin G binding protein A |

| WAN014G2F_at | sspB | 15 | 5 | SA1725 | Staphopain |

| WAN014HM5_at | 15 | 5 | SA0841 | Similar to cell surface protein Map-w | |

| WAN014HGC_at | 15 | 5 | SAR1816 | Putative membrane protein | |

Affymetrix S. aureus GeneChip (Saur2a) descriptive representing indicated predicted ORF or intergenic region.

Transcript half-life in min; 5 indicates <5 min, 15 indicates between 5 and 15 min, 30 indicates between 15 and 30 min, 60 indicates between 30 and 60 min, and stable indicates >60 min.

S. aureus strain N315 loci. Genes not contained within strain N315 but present in other sequenced S. aureus strains are indicated. SAV, MW, SAS, SAR, and SACOL preceeding a locus number correspond to Mu50, MW2, MSSA 476, MRSA 252, and COL loci.

Gene regions are represented separately and independently on the GeneChip.

WT, wild type.

Using real-time PCR, we confirmed that both cna and spa transcripts are more stable within wild-type cells than in sarA mutant cells. As shown in Table 5, cna and spa transcript titers decreased 2.6- and 2.7-fold, respectively, following 10 min of transcriptional arrest within wild-type cells. Within isogenic sarA mutant cells, the relative decrease in transcript abundance was >2,000- and 66.6-fold for spa and cna mRNA, respectively. In the case of spa mRNA, this relative degradation is not an accurate measurement. The reason for this is that, despite measuring high titers of spa transcript at the time of transcriptional arrest (T0), spa mRNA was undetectable at 10 min after rifampin treatment. Transcript stability could be restored to sarA mutant cells by complementation by a low-copy-number plasmid capable of producing the sarA transcriptional unit via its endogenous promoter, confirming that this phenomenon is due to the presence of the sarA locus as opposed to another previously unrecognized characteristic of the strain background. Moreover, the observed sarA-mediated change in mRNA stability was specific to spa and cna transcripts; S. aureus N315-SA1278 transcripts were unaffected by the presence or absence of the sarA locus.

TABLE 5.

Relative degradation of spa and cna transcripts

| Strain | Fold mRNA degradation ofa:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| spa | cna | SA1278 | |

| UAMS-1 | 2.7 (±1.1) | 2.6 (±1.7) | 1.0 (±0.8) |

| UAMS-929 (sarA) | 2,405.4 (±486.5) | 66.6 (±9.8) | 1.0 (±0.7) |

| UAMS-969 (sarA; pSARA) | 2.8 (±1.8) | 2.6 (±1.5) | ND |

Real-time PCR was used to determine the relative decrease in spa, cna, and strain N315 locus SA1278 transcript titers following 10 min of transcriptional arrest. ND, not determined.

DISCUSSION

Modulating mRNA maturation and degradation are recognized means of regulating bacterial gene expression. Although these processes have been well characterized in E. coli, and to a lesser extent B. subtilis, little is known about mRNA processing within staphylococci. In this work, we determined the S. aureus mRNA half-lives of log-phase transcripts as a first step toward understanding the organism's transcript turnover properties.

S. aureus mRNA molecules appear to undergo differential rates of degradation, suggesting that there may be previously unrecognized cis-acting mRNA elements or trans-acting factors that influence mRNA processing. It is intriguing to consider (i) what elements confer stability to these molecules, (ii) whether trans-acting factors temporally regulate transcript stability, and if so, (iii) whether the modulation of mRNA stability correlates with a previously unappreciated level of regulation within S. aureus. It seems plausible that modulating mRNA turnover is an efficient and dynamic means of posttranscriptional gene regulation that allows S. aureus to respond rapidly to endogenous and exogenous signals. Indeed, a number of other bacterial pathogens produce mRNA-binding proteins which influence virulence factor mRNA turnover and protein production. For instance, E. coli produces an RNA-binding protein, CsrA, that influences biofilm formation by altering pgaABCD transcript stability and, consequently, poly-B-1,6-N-acetyl-d-glucosamine production (60). CsrA homologs have been shown to influence virulence factor production in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, Erwinia carotovora subsp. carotovora, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (1, 32, 49). Although we have not identified a CsrA homolog within S. aureus, the finding that at least two virulence factor transcripts, cna and spa, are stabilized in a sarA-dependent manner suggests that trans-acting factors do modulate virulence factor mRNA turnover within S. aureus and may represent a previously unappreciated mechanism of regulation within this organism. We are currently evaluating whether this change in stability correlates to changes in protein abundance.

Although it was found that the sarA locus stabilizes spa and cna virulence factor transcripts, it is possible that this phenomenon is more global than initially observed. There are two main reasons for this. First, we measured the mRNA stability of log-phase cells. Many UAMS-1 virulence factors (and other genes) are preferentially transcribed during late-log-phase growth; thus, they were not expressed at our initial sampling time and could not be evaluated. Second, most virulence factors that were transcribed during log-phase growth decayed before the earliest post-transcriptional arrest measurement (5 min), making it difficult to discern whether sarA influenced the stability of those transcripts (a transcript's half-life might be 30 s in a sarA mutant but 3 min in wild-type cells).

The finding that spa and cna transcripts are stabilized in a sarA-dependent manner was unexpected. We anticipated that sarA's effect, if any, would be to accelerate the degradation rate of these two transcripts. The reason for this is that both collagen-binding protein and protein A production are repressed in a sarA-dependent manner. Accordingly, we hypothesized that SarA may lower the pool of target mRNA molecules available for translation via two mechanisms, repressing transcript synthesis and accelerating mRNA degradation of any basally produced transcripts. However, we found the opposite to be the case; these transcripts were stabilized by sarA. Although our initial hypothesis was incorrect, our observations could be explained by other scenarios. Because sarA is a negative regulator of Spa and Cna production, it is quite possible that it may act to both repress transcript synthesis and stabilize any transcripts that are basally produced in a manner that interferes with translation and delays degradation (degradosome accessibility). Indeed, within B. subtilis the 5′ end of a transcript not only serves as a potential entry point for the degradosome but also is the entry point for ribosomes during translation. Moreover, the binding of regulatory proteins and ribosome stalling within this region has been shown to increase B. subtilis mRNA stability (6, 28, 29). Accordingly, it is easy to imagine that SarA or a SarA-regulated molecule might bind this region of a transcript in a manner that simultaneously influences translation and degradation. Thus, there may be multiple layers by which sarA modulates gene expression. Alternatively, sarA may alter the transcriptional start site of affected transcripts in a manner that provides a 5′ stabilizing structure. Admittedly, we are in the initial stages of testing this hypothesis; nonetheless, these studies may have expanded significance in that SarA represents a prototypical regulatory molecule with a multitude of homologues within S. aureus and other bacterial pathogens.

Our results also indicate that S. aureus is capable of producing a set of extremely stable RNA molecules (half-life > 60 min) with no predicted open reading frame during log-phase growth. These transcripts were detected by GeneChip features representing intergenic regions of the S. aureus N315 genome and, based on size predictions, are expected to be ∼75 to 300 nt in length. Further analysis indicates that none of these transcripts maps to an ORF within any of the publicly available S. aureus genomes. Thus, many, if not all, of these RNA species may represent short, noncoding RNAs (also known as micro-RNAs and short interfering RNAs), which regulate essential processes within eukaryotic cells as well as stress responses and pathogenicity factors within bacteria. Because the GeneChip used in these studies contains oligonucleotides representing segments of these stable RNA molecules, we cannot accurately determine the full sequence of each species. Studies are under way to better characterize each of these molecules and determine whether they influence biological processes within S. aureus.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Christine Reekie for technical assistance with tables and figures.

This work is partially supported by American Heart Association grant 0535037N to P.M.D. K.L.A. was supported by a University of Nebraska Medical Center Assistantship award.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altier, C., M. Suyemoto, and S. D. Lawhon. 2000. Regulation of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium invasion genes by csrA. Infect. Immun. 68:6790-6797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arvidson, S., and K. Tegmark. 2001. Regulation of virulence determinants in Staphylococcus aureus. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 291:159-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Auner, H., M. Buckle, A. Deufel, T. Kutateladze, L. Lazarus, R. Mavathur, G. Muskhelishvili, I. Pemberton, R. Schneider, and A. Travers. 2003. Mechanism of transcriptional activation by FIS: role of core promoter structure and DNA topology. J. Mol. Biol. 331:331-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balandina, A., L. Claret, R. Hengge-Aronis, and J. Rouviere-Yaniv. 2001. The Escherichia coli histone-like protein HU regulates rpoS translation. Mol. Microbiol. 39:1069-1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bayer, M. G., J. H. Heinrichs, and A. L. Cheung. 1996. The molecular architecture of the sar locus in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 178:4563-4570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bechhofer, D. H., and D. Dubnau. 1987. Induced mRNA stability in Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:498-502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beenken, K. E., J. S. Blevins, and M. S. Smeltzer. 2003. Mutation of sarA in Staphylococcus aureus limits biofilm formation. Infect. Immun. 71:4206-4211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beenken, K. E., P. M. Dunman, F. McAleese, D. Macapagal, E. Murphy, S. J. Projan, J. S. Blevins, and M. S. Smeltzer. 2004. Global gene expression in Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. J. Bacteriol. 186:4665-4684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernardo, K., N. Pakulat, S. Fleer, A. Schnaith, O. Utermohlen, O. Krut, S. Muller, and M. Kronke. 2004. Subinhibitory concentrations of linezolid reduce Staphylococcus aureus virulence factor expression. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:546-555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blevins, J. S., K. E. Beenken, M. O. Elasri, B. K. Hurlburt, and M. S. Smeltzer. 2002. Strain-dependent differences in the regulatory roles of sarA and agr in Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 70:470-480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blevins, J. S., M. O. Elasri, S. D. Allmendinger, K. E. Beenken, R. A. Skinner, J. R. Thomas, and M. S. Smeltzer. 2003. Role of sarA in the pathogenesis of Staphylococcus aureus musculoskeletal infection. Infect. Immun. 71:516-523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blevins, J. S., A. F. Gillaspy, T. M. Rechtin, B. K. Hurlburt, and M. S. Smeltzer. 1999. The Staphylococcal accessory regulator (sar) represses transcription of the Staphylococcus aureus collagen adhesin gene (cna) in an agr-independent manner. Mol. Microbiol. 33:317-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brescia, C. C., M. K. Kaw, and D. D. Sledjeski. 2004. The DNA binding protein H-NS binds to and alters the stability of RNA in vitro and in vivo. J. Mol. Biol. 339:505-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brunskill, E. W., and K. W. Bayles. 1996. Identification and molecular characterization of a putative regulatory locus that affects autolysis in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 178:611-618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cairrao, F., A. Cruz, H. Mori, and C. M. Arraiano. 2003. Cold shock induction of RNase R and its role in the maturation of the quality control mediator SsrA/tmRNA. Mol. Microbiol. 50:1349-1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cassat, J. E., P. M. Dunman, F. McAleese, E. Murphy, S. J. Projan, and M. S. Smeltzer. 2005. Comparative genomics of Staphylococcus aureus musculoskeletal isolates. J. Bacteriol. 187:576-592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheung, A. L., A. S. Bayer, G. Zhang, H. Gresham, and Y. Q. Xiong. 2004. Regulation of virulence determinants in vitro and in vivo in Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 40:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheung, A. L., J. M. Koomey, C. A. Butler, S. J. Projan, and V. A. Fischetti. 1992. Regulation of exoprotein expression in Staphylococcus aureus by a locus (sar) distinct from agr. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:6462-6466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheung, A. L., K. Schmidt, B. Bateman, and A. C. Manna. 2001. SarS, a SarA homolog repressible by agr, is an activator of protein A synthesis in Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 69:2448-2455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chien, Y., A. C. Manna, S. J. Projan, and A. L. Cheung. 1999. SarA, a global regulator of virulence determinants in Staphylococcus aureus, binds to a conserved motif essential for sar-dependent gene regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 274:37169-37176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Condon, C. 2003. RNA processing and degradation in Bacillus subtilis. Microbiol. Mol. Biol Rev. 67:157-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deighan, P., A. Free, and C. J. Dorman. 2000. A role for the Escherichia coli H-NS-like protein StpA in OmpF porin expression through modulation of micF RNA stability. Mol. Microbiol. 38:126-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dunman, P. M., W. Mounts, F. McAleese, F. Immermann, D. Macapagal, E. Marsilio, L. McDougal, F. C. Tenover, P. A. Bradford, P. J. Petersen, S. J. Projan, and E. Murphy. 2004. Uses of Staphylococcus aureus GeneChips in genotyping and genetic composition analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:4275-4283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dunman, P. M., E. Murphy, S. Haney, D. Palacios, G. Tucker-Kellogg, S. Wu, E. L. Brown, R. J. Zagursky, D. Shlaes, and S. J. Projan. 2001. Transcription profiling-based identification of Staphylococcus aureus genes regulated by the agr and/or sarA loci. J. Bacteriol. 183:7341-7353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dworkin, J., A. J. Ninfa, and P. Model. 1998. A protein-induced DNA bend increases the specificity of a prokaryotic enhancer-binding protein. Genes Dev. 12:894-900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fournier, B., A. Klier, and G. Rapoport. 2001. The two-component system ArlS-ArlR is a regulator of virulence gene expression in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 41:247-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gillaspy, A. F., S. G. Hickmon, R. A. Skinner, J. R. Thomas, C. L. Nelson, and M. S. Smeltzer. 1995. Role of the accessory gene regulator (agr) in pathogenesis of staphylococcal osteomyelitis. Infect. Immun. 63:3373-3380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glatz, E., R. P. Nilsson, L. Rutberg, and B. Rutberg. 1996. A dual role for the Bacillus subtilis glpD leader and the GlpP protein in the regulated expression of glpD: antitermination and control of mRNA stability. Mol. Microbiol. 19:319-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glatz, E., M. Persson, and B. Rutberg. 1998. Antiterminator protein GlpP of Bacillus subtilis binds to glpD leader mRNA. Microbiology 144:449-456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ingavale, S., W. van Wamel, T. T. Luong, C. Y. Lee, and A. L. Cheung. 2005. Rat/MgrA, a regulator of autolysis, is a regulator of virulence genes in Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 73:1423-1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ingavale, S. S., W. Van Wamel, and A. L. Cheung. 2003. Characterization of RAT, an autolysis regulator in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 48:1451-1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johansson, J., and P. Cossart. 2003. RNA-mediated control of virulence gene expression in bacterial pathogens. Trends Microbiol. 11:280-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Julio, S. M., D. M. Heithoff, and M. J. Mahan. 2000. ssrA (tmRNA) plays a role in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium pathogenesis. J. Bacteriol. 182:1558-1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karlsson, A., P. Saravia-Otten, K. Tegmark, E. Morfeldt, and S. Arvidson. 2001. Decreased amounts of cell wall-associated protein A and fibronectin-binding proteins in Staphylococcus aureus sarA mutants due to up-regulation of extracellular proteases. Infect. Immun. 69:4742-4748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kornblum, J., B. N. Kreiswirth, S. J. Projan, H. Ross, and R. P. Novick. 1990. Agr: a polycistronic locus regulating exoprotein synthesis in Staphylococcus aureus, p. 373-402. In R. P. Novick (ed.), Molecular biology of the staphylococci. VCH Publishers, New York, N.Y.

- 36.Kupferwasser, L. I., M. R. Yeaman, C. C. Nast, D. Kupferwasser, Y. Q. Xiong, M. Palma, A. L. Cheung, and A. S. Bayer. 2003. Salicylic acid attenuates virulence in endovascular infections by targeting global regulatory pathways in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Investig. 112:222-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuroda, M., H. Kuroda, T. Oshima, F. Takeuchi, H. Mori, and K. Hiramatsu. 2003. Two-component system VraSR positively modulates the regulation of cell-wall biosynthesis pathway in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 49:807-821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee, K. Y., and T. H. Birkbeck. 1984. In vitro synthesis of the delta-lysin of Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 44:434-438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lindsay, J. A., and M. T. Holden. 2004. Staphylococcus aureus: superbug, super genome? Trends Microbiol. 12:378-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Manna, A., and A. L. Cheung. 2001. Characterization of sarR, a modulator of sar expression in Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 69:885-896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Manna, A. C., M. G. Bayer, and A. L. Cheung. 1998. Transcriptional analysis of different promoters in the sar locus in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 180:3828-3836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manna, A. C., and A. L. Cheung. 2003. sarU, a sarA homolog, is repressed by SarT and regulates virulence genes in Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 71:343-353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Manna, A. C., S. S. Ingavale, M. Maloney, W. van Wamel, and A. L. Cheung. 2004. Identification of sarV (SA2062), a new transcriptional regulator, is repressed by SarA and MgrA (SA0641) and involved in the regulation of autolysis in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 186:5267-5280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martin, P. K., T. Li, D. Sun, D. P. Biek, and M. B. Schmid. 1999. Role in cell permeability of an essential two-component system in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 181:3666-3673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McCallum, N., M. Bischoff, H. Maki, A. Wada, and B. Berger-Bachi. 2004. TcaR, a putative MarR-like regulator of sarS expression. J. Bacteriol. 186:2966-2972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Novick, R. P. 2000. Pathogenicity factors and their regulation, p. 392-407. In V. A. Fischetti, R. P. Novick, J. J. Ferretti, D. A. Portnoy, and J. I. Rood (ed.), Gram-positive pathogens. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 47.Novick, R. P., and D. Jiang. 2003. The staphylococcal saeRS system coordinates environmental signals with agr quorum sensing. Microbiology 149:2709-2717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Novick, R. P., H. F. Ross, S. J. Projan, J. Kornblum, B. Kreiswirth, and S. Moghazeh. 1993. Synthesis of staphylococcal virulence factors is controlled by a regulatory RNA molecule. EMBO J. 12:3967-3975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pessi, G., F. Williams, Z. Hindle, K. Heurlier, M. T. Holden, M. Camara, D. Haas, and P. Williams. 2001. The global posttranscriptional regulator RsmA modulates production of virulence determinants and N-acylhomoserine lactones in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 183:6676-6683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pichon, C., and B. Felden. 2005. Small RNA genes expressed from Staphylococcus aureusgenomic and pathogenicity islands with specific expression among pathogenic strains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:14249-14254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schmidt, K. A., A. C. Manna, S. Gill, and A. L. Cheung. 2001. SarT, a repressor of alpha-hemolysin in Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 69:4749-4758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schumacher, M. A., B. K. Hurlburt, and R. G. Brennan. 2001. Crystal structures of SarA, a pleiotropic regulator of virulence genes in S. aureus. Nature 409:215-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Selinger, D. W., R. M. Saxena, K. J. Cheung, G. M. Church, and C. Rosenow. 2003. Global RNA half-life analysis in Escherichia coli reveals positional patterns of transcript degradation. Genome Res. 13:216-223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Spitzfaden, C., N. Nicholson, J. J. Jones, S. Guth, R. Lehr, C. D. Prescott, L. A. Hegg, and D. S. Eggleston. 2000. The structure of ribonuclease P protein from Staphylococcus aureus reveals a unique binding site for single-stranded RNA. J. Mol. Biol. 295:105-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Steinhuber, A., C. Goerke, M. G. Bayer, G. Doring, and C. Wolz. 2003. Molecular architecture of the regulatory locus sae of Staphylococcus aureus and its impact on expression of virulence factors. J. Bacteriol. 185:6278-6286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sterba, K. M., S. G. Mackintosh, J. S. Blevins, B. K. Hurlburt, and M. S. Smeltzer. 2003. Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus SarA binding sites. J. Bacteriol. 185:4410-4417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tegmark, K., A. Karlsson, and S. Arvidson. 2000. Identification and characterization of SarH1, a new global regulator of virulence gene expression in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 37:398-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tupper, A. E., T. A. Owen-Hughes, D. W. Ussery, D. S. Santos, D. J. Ferguson, J. M. Sidebotham, J. C. Hinton, and C. F. Higgins. 1994. The chromatin-associated protein H-NS alters DNA topology in vitro. EMBO J. 13:258-268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ussery, D., T. S. Larsen, K. T. Wilkes, C. Friis, P. Worning, A. Krogh, and S. Brunak. 2001. Genome organisation and chromatin structure in Escherichia coli. Biochimie 83:201-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang, X., A. K. Dubey, K. Suzuki, C. S. Baker, P. Babitzke, and T. Romeo. 2005. CsrA post-transcriptionally represses pgaABCD, responsible for synthesis of a biofilm polysaccharide adhesin of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 56:1648-1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weinrick, B., P. M. Dunman, F. McAleese, E. Murphy, S. J. Projan, Y. Fang, and R. P. Novick. 2004. Effect of mild acid on gene expression in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 186:8407-8423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yarwood, J. M., J. K. McCormick, and P. M. Schlievert. 2001. Identification of a novel two-component regulatory system that acts in global regulation of virulence factors of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 183:1113-1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.