Abstract

Vibrio cholerae, the causative agent of cholera, is a normal inhabitant of aquatic environments, where it survives in a wide range of conditions of pH and salinity. In this work, we investigated the role of three Na+/H+ antiporters on the survival of V. cholerae in a saline environment. We have previously cloned the Vc-nhaA gene encoding the V. cholerae homolog of Escherichia coli. Here we identified two additional antiporter genes, designated Vc-nhaB and Vc-nhaD, encoding two putative proteins of 530 and 477 residues, respectively, highly homologous to the respective antiporters of Vibrio species and E. coli. We showed that both Vc-NhaA and Vc-NhaB confer Na+ resistance and that Vc-NhaA displays an antiport activity in E. coli, which is similar in magnitude, kinetic parameters, and pH regulation to that of E. coli NhaA. To determine the roles of the Na+/H+ antiporters in V. cholerae, we constructed nhaA, nhaB, and nhaD mutants (single, double, and triple mutants). In contrast to E. coli, the inactivation of the three putative antiporter genes (Vc-nhaABD) in V. cholerae did not alter the bacterial exponential growth in the presence of high Na+ concentrations and had only a slight effect in the stationary phase. In contrast, a pronounced and similar Li+-sensitive phenotype was found with all mutants lacking Vc-nhaA during the exponential phase of growth and also with the triple mutant in the stationary phase of growth. By using 2-n-nonyl-4-hydroxyquinoline N-oxide, a specific inhibitor of the electron-transport-linked Na+ pump NADH-quinone oxidoreductase (NQR), we determined that in the absence of NQR activity, the Vc-NhaA Na+/H+ antiporter activity becomes essential for the resistance of V. cholerae to Na+ at alkaline pH. Since the ion pump NQR is Na+ specific, we suggest that its activity masks the Na+/H+ but not the Li+/H+ antiporter activities. Our results indicate that the Na+ resistance of the human pathogen V. cholerae requires a complex molecular system involving multiple antiporters and the NQR pump.

Cholera is a severe human diarrheal disease caused by Vibrio cholerae, which colonizes the small intestine of humans and produces the cholera toxin (10). V. cholerae is a normal inhabitant of aquatic environments, belonging to the free-living bacterial flora in estuarine areas (5). It is endemic in the Indian subcontinent and disseminates worldwide through major outbreaks, and it is particularly associated with poverty and poor sanitation (1). The V. cholerae pathogenic strains are mainly transmitted by contaminated water and food and belong to two major serogroups, O1 and O139 (2, 39). Their natural niche includes crustacea or mollusks as a part of the zooplankton (4, 37). V. cholerae is a halotolerant microorganism whose growth is stimulated by sodium, and it survives in a wide range of conditions of salinity and pH. Indeed, V. cholerae strains are mostly isolated from environmental sites with NaCl concentrations between 0.2 and 2.0 g/100 ml (5). In vitro, the bacteria survives in 0.25 to 3.0% salt with an optimal salinity of 2.0% (21). Moreover, the optimal pH for survival ranges from 7.0 to 9.0, depending upon salinity (21). All these data suggest that V. cholerae has developed complex molecular mechanisms to grow and survive in saline environments.

It is known that all living cells, eukaryotes as well as prokaryotes, maintain a sodium concentration gradient directed inward and a constant intracellular pH around neutral (29). Na+/H+ antiporters play a primary role in these homeostatic mechanisms (16, 20, 28, 45) and are ubiquitous proteins inserted in cytoplasmic membranes of cells and in membranes of many organelles. In Escherichia coli, genes for the three distinct antiporters nhaA (18), nhaB (32), and chaA (17) have been characterized already. The NhaA and NhaB antiporters of E. coli specifically exchange Na+ or Li+ for H+ (33, 41). NhaA is required for adaptation to high salinity, resistance to Li+ toxicity, and growth at alkaline pH in the presence of Na+ (28). NhaB confers a limited sodium tolerance to bacteria but becomes essential when the lack of NhaA limits growth (30).

E. coli nhaA has a dual mode of regulation of transcription, each involving a different promoter. During the logarithmic phase of growth, the expression of nhaA is positively regulated by NhaR, a member of the LysR family (34), Na+ is the inducer, and P1 is the Na+-specific promoter which is transcribed by σ70. In the stationary phase, σs transcribes nhaA via P2 in a fashion which is independent of Na+ and NhaR.

Little is known about the Na+/H+ antiporters of the genus Vibrio. NhaA and NhaB homologs have been identified in Vibrio parahaemolyticus and in Vibrio alginolyticus, two closely related aquatic species (19, 23, 25, 26). We recently cloned and characterized a 35-kDa NhaA of V. cholerae (designated Vc-NhaA), highly homologous to NhaA of E. coli (44). In addition, a homolog of E. coli NhaR (60% identity) has also been recently described (49). Interestingly, a third antiporter, named NhaD, was recently identified in V. parahaemolyticus (27) and V. cholerae (8). nhaD of V. cholerae (designated Vc-nhaD) was cloned and found to confer Na+ resistance to a Na+-sensitive E. coli nhaA nhaB mutant and to express Na+(Li+)/H+ antiporter activity in isolated membrane vesicles of the E. coli host (8).

In this work, we investigated the role of the Na+/H+ antiporters NhaA, NhaB, and NhaD in the survival of V. cholerae in a saline environment. For this purpose, we cloned V. cholerae NhaB and studied the properties of both Vc-NhaA (44) and Vc-NhaB antiporters in E. coli. We found that V. cholerae NhaA and NhaB express an antiporter activity in E. coli. Vc-NhaA possesses a pH profile similar to that of E. coli. By constructing a series of V. cholerae antiporter mutants (Vc-nhaA, Vc-nhaB, Vc-nhaD, Vc-nhaAB, Vc-nhaAD, Vc-nhaBD, and Vc-nhaABD) and inhibition of the NADH-quinone oxidoreductase (NQR) primary Na+ pump, we revealed the contribution of Vc-NhaA Na+/H+ antiporter to the survival of V. cholerae during the stationary and exponential growth phases in a saline environment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture media.

In most experiments we used the N18 V. cholerae O1 wild-type strain, isolated in 1991 from a patient during the cholera epidemic in Peru. V. cholerae strain O395 was obtained from C. Parsot (Institut Pasteur, Paris, France), and V. alginolyticus strain 255 was obtained from J. M. Fournier (Institut Pasteur). For DNA manipulations, we used the E. coli strains and plasmids listed in Table 1. E. coli strain β2155 was obtained from D. Mazel (Institut Pasteur), and E. coli strains TG1 and KNabc were obtained from T. Tsuchiya (Faculty of Pharmaceutical Science, Okayama University, Okayama, Japan). Bacteria were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth, modified LB broth in which NaCl was replaced by KCl (87 mM) (LBK), or nutrient broth (NB) (10 g each of Oxoid Lab Lemco and Oxoid Bacto Peptone per liter; Oxoid, Dardilly, France). When indicated, NaCl or LiCl was added and the pH was adjusted with 20 mM Tricine-KOH or 60 mM BTP {1,3 bis-[Tris (hydroxymethyl)-methylamino]propane} (Sigma, St. Quentin Fallavier, France). E. coli β2155 was grown in LB broth supplemented with diamino-pimelic acid (1 mM). The concentrations of the antibiotics used were the following: 100 mg of ampicillin/liter, 50 mg of kanamycin/liter, 10 mg of gentamicin/liter, 10 mg of chloramphenicol/liter, 12.5 mg of tetracycline/liter. Bacterial growth was usually followed by the measurement of turbidity at 600 nm or by counting CFU on agar plates after serial dilutions.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s)a | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| V. cholerae | ||

| N18 | Isolated in Peru in 1991, O1 serotype, E1 Tor biotype | J. M. Fournier (Institut Pasteur) |

| O395 | O1 serotype, classical biotype | C. Parsot (Institut Pasteur) |

| NA | N18 nhaA mutant (SV1) | 44 |

| NB | N18 nhaB mutant | This work |

| ND | N18 nhaD mutant | This work |

| NAB | N18 nhaA nhaB mutant | This work |

| NAD | N18 nhaA nhaD mutant | This work |

| NBD | N18 nhaB nhaD mutant | This work |

| NABD | N18 nhaA nhaB nhaD mutant | This work |

| E. coli (all are strain K-12 derivatives) | ||

| DH5α | recA1 gyrA (Nal) Δ(lacIZYA-argF) (φ80dlac Δ[lacZ]M15), pir RK6 | |

| DH5α λpir | recA1 gyrA (Nal), Δ(lacIZYA-argF) (φ80dlacΔ[lacZ]M15), pir RK6 | 22 |

| β2155 | F′ traD36 lacIq Δ(lacZ)M15 proA+B+/thr-1004 pro thi strA hsdS Δ(lacZ)M15 ΔdapA::erm pir::RP4 (::kan from SM10) | D. Mazel (Institut Pasteur), unpublished data |

| TG1 | F′ traD36 lacIq Δ(lacZ)M15 proA+B+/supE Δ(hsdM-mcrB)5 (rK−mK− McrB−) thi Δ(lac-proAB) | 26 |

| KNabc | TG1 (ΔnhaA ΔnhaB ΔchaA) | 26 |

| EP432 | melBLid ΔnhaA1::kan ΔnhaB1::cam ΔlacZY thr1 | 30 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pHG329 | Amp+ | 40 |

| pBR322 | Amp+, Tet+ | 47 |

| pCVD442 | Suicide vector composed of the mob, ori, and bla regions from pGP704 and the sacB gene of B. subtilis | 6 |

| pNOT218Apra | G+, a pNOT218 derivative with a 1,031-kb SmaI fragment containing aac3-IV inserted at the SmaI site | 3, 36 |

| pCVDnhaB:G | Amp+, G+, a pCVD442 derivative, with a 3.4-kb XbaI-SphI fragment containing aac3-IV inserted at the SacI site of a 2.3-kb PstI fragment containing the nhaB gene | This work |

| pHSG576 | Cm+ | 42 |

| pCVDnhaD:CAT | Amp+, Cm+, a pCVD442 derivative, with a 2.4-kb XbaI-SphI fragment containing CAT inserted at the StuI site of a 1.5-kb PCR fragment containing the nhaB gene | This work |

| pGM36 | pBR322 derivative, contains nhaA from E. coli | 11 |

| pHG329Vc-nhaA | pHG329 derivative, contains the nhaA gene from V. cholerae | 44 |

| pHG329Vc-nhaB | pHG329 derivative, contains the nhaB gene from V. cholerae | This work |

| pHG329Vc-nhaD | pHG329 derivative, contains the nhaD gene from V. cholerae | This work |

| pBR322Vc-nhaA | pBR322 derivative, contains the nhaA gene from V. cholerae | This work |

| pBR322Vc-nhaB | pBR322 derivative, contains the nhaB gene from V. cholerae | This work |

| pBR322Vc-nhaD | pBR322 derivative, contains the nhaD gene from V. cholerae | This work |

| pEL24 | Amp+, Kan+, contains nhaB from E. coli | 30 |

Amp, Tet, G, Cm, and Kan, resistance to ampicillin, tetracycline, gentamycin, chloramphenicol, and kanamycin, respectively.

To study survival during stationary phase, bacteria grown for 16 h on LBK-BTP medium at 37°C were exposed for 3 h to the indicated pHs and to various concentrations of NaCl or LiCl (0.2 to 0.8 M) and then were plated on LBK agar to determine the number of CFU.

Bacteria were also exposed to 2-n-nonyl-4-hydroxyquinoline N-oxide (NQNO) (kindly donated by Y. Shahak, The Volcani Center, Bet-Dagan, Israel) during exponential growth phase. Bacteria were grown overnight in LB broth and were diluted 1:500 into LB-BTP (pH 9.0) with or without NQNO (12.5 μM). Serial dilutions were plated on LB plates after 0, 3, and 10 h of incubation. NQNO was prepared in ethanol.

DNA manipulations and sequencing.

Chromosomal DNA purification, DNA ligation, bacterial transformation, agarose gel electrophoresis, colony hybridization, and Southern blotting were carried out by standard techniques, as described previously (38). Plasmid DNA was purified on QIAGEN columns (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France) or by using the Concert Rapid Plasmid Miniprep System (Gibco-BRL-Life Technologies, Eragny, France). All restriction enzymes and nucleic-acid-modifying enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs (Ozyme, St. Quentin en Yvelines, France). [α−32P]dCTP was obtained from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Orsay, France). Oligonucleotides were purchased from Genset (Evry, France). PCR was used to prepare probes and to clone DNA fragments by using a Perkin-Elmer DNA Thermal Cycler 480 (Applied Biosystems, Les Ullis, France). V. cholerae chromosomal DNA (100 ng) was mixed in a final volume of 100 μl with 200 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 40 pmol of each primer, 2 U of Taq polymerase (Promega, Charbonnières, France), and reaction buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], 50 mM KCl, and 1.5 mM MgCl2). The PCR mixture was subjected to a denaturation step (5 min at 95°C) followed by 35 cycles of amplification (60 s of denaturation at 95°C, 60 s of annealing at 55°C, and 90 or 120 s of elongation at 72°C) and a termination step (10 min at 72°C). The resulting amplicons were purified from agarose gels with a Geneclean kit (Bio 101; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The nucleotide sequence was determined by the dideoxy-chain termination method with the ABI PRISM Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems) and the ABI PRISM 310 automatic sequencer (Applied Biosystems). Computer analysis was carried out by using the Mac Vector program (International Biotechnologies Inc.) and the National Center for Biotechnology Information website (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Multiple sequence alignment of deduced peptide sequences was carried out by using Clustal W (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/clustalw/index.html).

Cloning of nhaB and complementation.

Chromosomal DNA from V. cholerae O1 (N18) was digested with HindIII, and 4- to 10-kb DNA fragments selected by centrifugation on a sucrose gradient were cloned into pBR322 and used to transform E. coli DH5α. The Vc-nhaB gene was then cloned from this library by using an nhaB probe from V. alginolyticus (1,585 bp) obtained by PCR with the primers 5′-ATGCCGATATCGCTCGGAAAC-3′ and 5′-TTAGTGACCGCCGGAGACTAC-3′. For complementation assays, a 2,170-bp HincII fragment derived from the 6,634-kb fragment of the HindIII genomic library and containing the entire Vc-nhaB was inserted into pHG329 and pBR322 to give pHG329Vc-nhaB and pBR322Vc-nhaB, respectively. Cloning of pHG329VcnhaA has been previously described (44). Vc-nhaA was cloned into pBR322 to give pBR322Vc-nhaA.

Construction of the nhaB, nhaD, nhaAB, nhaAD, nhaBD, and nhaABD mutants.

For construction of an nhaB-disrupted mutant of strain N18 of V. cholerae O1, a 2,305-bp PstI fragment derived from the 6,634-bp HindIII fragment of the genomic library was inserted into pHG329, previously deleted from its SacI cloning site. A gentamicin resistance cassette (aac3-IV), obtained by SmaI digestion of pNOT218Apra, was cloned into the SacI-blunted site of the nhaB gene. The resulting 3,400-bp XbaI-SphI fragment containing the nhaB gene with the gentamicin resistance cassette was inserted into the suicide vector pCVD442 to give pCVDnhaB:G. All the constructs were made in E. coli DH5α except for the final step, which was made in E. coli strain DH5α λpir. pCVDnhaB:G was used to transform E. coli β2155, from which the plasmid was transferred into the wild-type V. cholerae strain by conjugation as previously described (44). Ampicillin and gentamicin double-resistant colonies contained the pCVDnhaB:G plasmid integrated into the chromosome by homologous recombination involving either the upstream or downstream fragments of nhaB, with creation of a merodiploid state. One such colony was selected and grown overnight in LB medium without selection, plated on LB medium-gentamicin with 2% sucrose but without NaCl, and grown at 30°C for 18 to 30 h, thereby selecting for clones that had deleted the integrated sacB gene. The genotype of the nhaB V. cholerae mutant (NB) was confirmed by Southern blot analysis.

We also constructed an nhaD-disrupted mutant from strain N18 of V. cholerae O1 by insertion of a chloramphenicol resistance cassette into the StuI site of the gene. A 1,514-bp PCR fragment containing the nhaD gene was generated by using V. cholerae O1 chromosomal DNA as a template with the primers 5′-AGCCTGCAGCCACAACAAACCA-3′ and 5′-CTGCTGCAGAGCCAATCGATAGCA -3′. This fragment was flanked by PstI restriction sites which were used for cloning into the vector pHG329. A 898-bp PCR fragment containing a chloramphenicol resistance cassette was generated by using pHSG576 as template with the primers 5′-GAACCCGGGTAAATGGCACT-3′ and 5′-CTGCCCGGGAAAAATTACGCCC-3′. This fragment was flanked by SmaI restriction sites which were used to insert it into the StuI site of the nhaD gene. The resulting 2,400-bp XbaI-SphI fragment containing the nhaD gene with the chloramphenicol resistance cassette was inserted into the suicide vector pCVD442 to give pCVDnhaD:CAT. The nhaD V. cholerae mutant (ND) was obtained by the same method described for the NB mutant, with chloramphenicol selection instead of the gentamicin selection. Its genotype was confirmed by PCR.

An nhaBD double mutant (NBD) was constructed in the same way as the ND mutant but with the NB mutant as the recipient strain instead of the wild-type strain. nhaAB (NAB), nhaAD (NAD), or nhaABD (NABD) mutants were constructed as previously described (44) by the integration of the suicide vector pSV1 containing an internal fragment of nhaA into the chromosomal nhaA gene of the NB, ND, or NBD V. cholerae mutants, respectively. Their genotypes were confirmed by PCR. All these constructs were performed in strains N18 and O395 of V. cholerae with similar results.

Isolation of everted membrane vesicles and Na+/H+ antiporter activity assay.

If not otherwise stated, Na+/H+ antiporter activity assays were conducted on everted membrane vesicles prepared from cells grown in LBK at pH 7.5 (35). The antiporter activity was assayed as described previously (28) in a reaction mixture that contained 50 to 100 μg of membrane protein, 140 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM BTP adjusted to the indicated pH, and 0.5 μM acridine orange, for which steady-state fluorescence was measured in a Perkin-Elmer fluorimeter (Applied Biosystems) at 490 nm excitation and 530 nm emission. ΔpH (transmembrane pH gradient) was established by the addition of 2 mM d-lactate or 2 mM ATP, detected by the quenching of the fluorescence, and estimated from the new steady-state level of fluorescence. The antiporter activity was measured from the dequenching of fluorescence upon the subsequent addition of 10 mM NaCl or LiCl. Total membrane protein was determined as previously described (50).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nhaB nucleotide sequence from V. cholerae O1 strain N18 has been entered into the GenBank nucleotide sequence database under the accession number AF489522.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Identification of nhaB of V. cholerae.

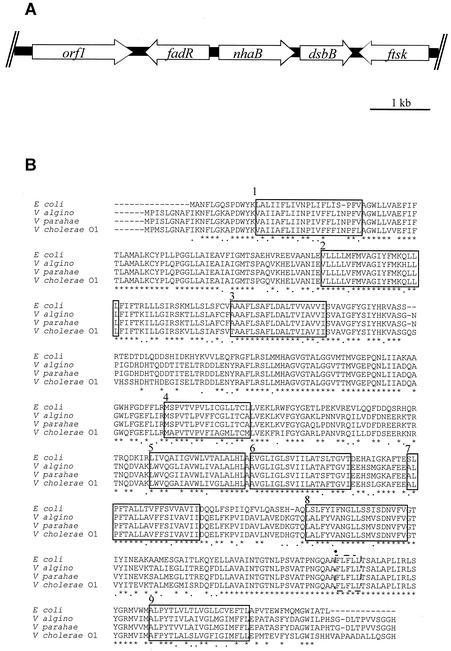

A HindIII genomic library was constructed from wild-type epidemic strain N18 of V. cholerae O1. This library was screened with an nhaB probe from V. alginolyticus under conditions of high stringency. A positive clone carrying a 6.5-kb HindIII fragment was isolated, and its DNA sequence (6,634 bp) revealed the presence of 5 open reading frames (ORFs), including a homolog (orf3) of nhaB of V. parahaemolyticus and V. alginolyticus (Fig. 1). orf1 encodes a putative protein of unknown function, and orf2 encodes a putative protein highly homologous to the multifunctional regulator of fatty acid metabolism, FadR of V. alginolyticus (95% identity on 126 residues), Yersinia pestis (53%), E. coli (52%), and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (51%). orf4 encodes a putative protein highly homologous to the disulfide-bond-forming protein, DsbB (also known as disulfide oxidoreductase), of V. alginolyticus (70% identity), Y. pestis (51%), E. coli (46%), and Shigella flexneri (45%). orf5 encodes a putative protein highly homologous to a putative cell division protein, FtsK, of Y. pestis (75% identity), S. enterica serovar Typhi (75%), S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (75%), E. coli (74%), Neisseria meningitidis (66%), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (64%), for example.

FIG. 1.

(A) Genetic organization of the nhaB locus of V. cholerae O1. (B) Clustal W alignment of NhaB of E. coli, V. alginolyticus (V algino), V. parahaemolyticus (V parahae), and V. cholerae N18. Asterisks indicate amino acid identity, and dots indicate amino acid similarity. Helical structures spanning the membrane are indicated with open boxes and are numbered. They were deduced by comparison with the NhaB two-dimensional model of V. alginolyticus (9). The putative amiloride-binding site is indicated with a black circle.

The genomic organization of the nhaB region of V. cholerae (Fig. 1) is similar to that of V. alginolyticus but differs from that of E. coli, where dsbB is not present downstream from nhaB (23, 32). The nhaB gene of V. cholerae N18 (designated Vc-nhaB) is predicted to encode a protein of 530 residues, highly homologous to the NhaB antiporters of V. alginolyticus and V. parahaemolyticus (85% identity), E. coli (69%), Y. pestis (68%), S. enterica serovar Typhi (68%), S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (68%), Pasteurella multocida (67%), Haemophilus influenzae (67%), and P. aeruginosa (61%), suggesting that these proteins might share functional properties. The deduced peptide sequence of Vc-NhaB predicts the same polytopic structure as that of V. alginolyticus NhaB, with 9 putative transmembrane segments (9). Moreover, V. cholerae NhaB sequence analysis revealed in the third transmembrane region the presence of aspartate 147 (D147). Aspartate located at a similar position has been suggested to be involved in the antiporter activity of V. alginolyticus NhaB (24). Vc-NhaB also presents the 459FLFLL464 pentamer, which is presumably implicated in the amiloride binding site of prokaryotic NhaB proteins and eukaryotic antiporters, including mammalian NHE1 (164VFFLFLLPPI173). This diuretic drug is a potent inhibitor of purified E. coli NhaB, in contrast to E. coli NhaA (31).

Analysis of the V. cholerae El Tor N16961 genome sequence (14) revealed the presence of an ORF encoding a putative protein highly homologous to NhaD of V. parahaemolyticus (27). The nhaD gene of V. cholerae N18 (Vc-nhaD) encodes a predicted protein of 477 residues with 77% peptidic identity with NhaD of V. parahaemolyticus. Moreover, V. cholerae NhaD displays the same 301KTXXHXLA308 sequence as V. parahaemolyticus NhaD, presumably implicated in pH sensitivity (27). Recently and independently, nhaD has been cloned, expressed in E. coli, and found to encode a Na+/H+ antiporter (8). We therefore did not continue to characterize the NhaD protein.

Growth in a saline environment of E. coli antiporter mutants transformed with plasmids carrying Vc-nhaA and Vc-nhaB.

To study the Na+ resistance conferred by Vc-NhaA and Vc-NhaB, we transformed either the EP432 E. coli strain, an nhaA nhaB mutant (30), or the KNabc E. coli strain, which is an nhaA nhaB chaA mutant (26), with pBR322 Vc-nhaA or pBR322 Vc-nhaB (see Materials and Methods). Due to the lack of the antiporters, both EP432 and KNabc are Na+ sensitive, and their membrane vesicles are devoid of specific Na+/H+ antiporter activity. Therefore, these strains allowed us to study Na+ resistance conferred by the heterologous antiporter genes and to monitor, without background, the encoded antiporter activity.

The EP432/pBR322 Vc-nhaA strain was grown on LB-BTP agar plates (see Materials and Methods) containing 0.2 to 0.6 M NaCl at pH 7.0 or 8.3. pGM36, containing an insert encoding the wild-type nhaA gene of E. coli (designated Ec-nhaA), and pBR322 served as positive and negative controls, respectively. The results summarized in Table 2 show that at pH 7.0, EP432/pBR322 Vc-nhaA exhibits a resistance to Na+ similar to that of EP432/pGM36. In contrast, at pH 8.3, as reflected in a smaller size of the colonies, the Na+ resistance conferred by Vc-nhaA was lower than that conferred by Ec-nhaA.

TABLE 2.

Na+ resistance conferred by Vc-NhaA and Vc-NhaB in E. coli at various pHsa

| E. coli mutant and transforming plasmid | Na+ resistance at the indicated NaCl concn

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH 7.0

|

pH 8.3

|

||||

| 0.2 M | 0.4 M | 0.6 M | 0.2 M | 0.6 M | |

| EP432 | |||||

| pGM36(Ec-nhaA) | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| pBR322Vc-nhaA | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | + |

| pEL24(Ec-nhaB) | +++ | ND | ++ | − | − |

| pBR322Vc-nhaB | ++ | ND | − | − | − |

| pBR322 | − | − | − | − | − |

| KNabc | |||||

| pGM36(Ec-nhaA) | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | + |

| pEL24(Ec-nhaB) | +++ | ++ | + | − | − |

| pBR322Vc-nhaB | ++ | + | − | − | − |

| pBR322 | − | − | − | − | − |

The various transformants were grown on LB-BTP agar plates containing the indicated Na+ concentrations at the indicated pHs. +++, full number and size of colonies; ++ and +, the same number of colonies but with decreasing size; −, no growth; ND, not determined. Each experiment was conducted three times with basically identical results.

The generation time of EP432/pBR322 Vc-nhaA was then determined at various Na+ concentrations in liquid medium at pH 8.0 and 8.3 and was compared to that of EP432/pGM36 (Table 3). At pH 8.0 in the presence of 0.2 M NaCl, the doubling time of bacteria harboring plasmid copies of Ec-nhaA was very similar to that containing Vc-nhaA (32 and 37 min, respectively). However, a pronounced difference in the doubling time of the two strains was observed upon increasing the Na+ concentration to 0.4 M NaCl (42 and 58 min, respectively). At 0.6 M NaCl, only EP432/pGM36 grew with a doubling time of 60 min. At similar Na+ concentrations, increasing the pH to 8.3 slowed down the growth of both strains, but the effect was slightly more pronounced on EP432/pBR322 Vc-nhaA (Table 3). Thus, although slightly less efficient than Ec-NhaA, Vc-NhaA confers Na+ resistance (both on solid and in liquid medium) when expressed in E. coli.

TABLE 3.

Generation time of Vc-nhaA-transformed EP432 in liquid medium at alkaline pH and various salt concentrationsa

| pH and plasmid | Generation time (min) at the indicated NaCl concn

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.2 M | 0.4 M | 0.6 M | |

| 8.0 | |||

| pGM36(Ec-nhaA) | 32 | 42 | 60 |

| pBR322Vc-nhaA | 37 | 58 | No growth |

| 8.3 | |||

| pGM36(Ec-nhaA) | 43 | 46 | 70 |

| pBR322Vc-nhaA | 56 | 60 | No growth |

Cells were grown in LB-BTP containing the indicated concentrations of NaCl at pH 8.0 or 8.3, and the exponential doubling time was determined.

The same strategy was used to study Na+ resistance conferred by Vc-NhaB by using EP432 or KNabc as hosts and cells transformed with plasmid pEL24 that encodes E. coli NhaB (Ec-NhaB) as a positive control. As previously shown (26), the KNabc strain is more susceptible to Na+ than the EP432 strain (Table 2). Thus, whereas EP432 transformed with Ec-nhaA grows well in the presence of 0.6 M NaCl even at pH 8.3, a reduced resistance was found with E. coli KNabc containing Ec-nhaA. A decrease in the size of colonies was already observed in the presence of 0.6 M NaCl at pH 7.0 and in the presence of 0.2 M NaCl at pH 8.3 (Table 2). At pH 7.0, Vc-nhaB conferred resistance to Na+ (0.2 M) in both E. coli EP432 and KNabc strains, and in the latter strain resistance was monitored up to 0.4 M NaCl (Table 2). However, this Na+ resistance was lower than that conferred by Ec-NhaB, which grew up to 0.6 M NaCl in both strains. Similar to Ec-NhaB at pH 8.3, Vc-NhaB did not confer any Na+ resistance.

Antiporter activity of Vc-NhaA and Vc-NhaB in everted membrane vesicles of E. coli.

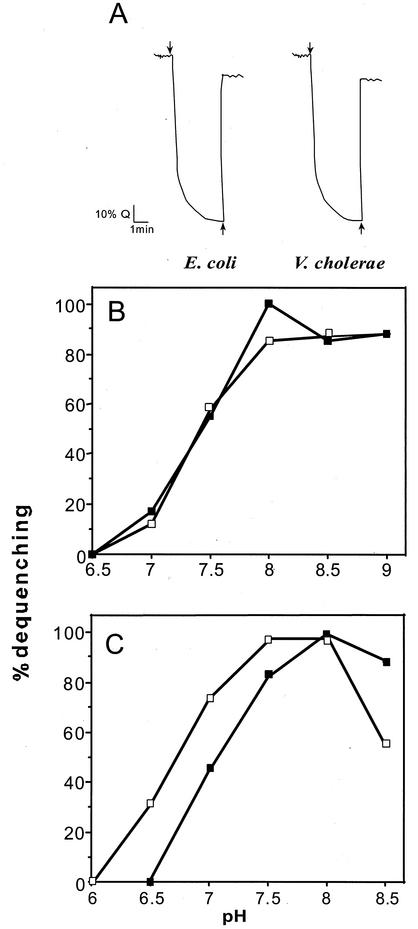

We determined the Na+/H+ antiporter activity of Vc-NhaA and Vc-NhaB by using everted membrane vesicles isolated from E. coli EP432 expressing Vc-NhaA or Vc-NhaB. The determination of Na+/H+ or Li+/H+ antiporter activity was based upon the measurement of Na+- or Li+-induced changes in the ΔpH by using a fluorescent probe to monitor ΔpH as previously described (11). Everted membrane vesicles isolated from E. coli EP432/pGM36 and from EP432/pBR322 strains were used as positive and negative controls, respectively.

The results obtained with EP432/pBR322 Vc-nhaA bacteria are illustrated in Fig. 2A. The pattern of the Na+/H+ activity of Vc-NhaA at pH 8.5 is very similar to that of Ec-NhaA. The kinetic parameters of Vc-NhaA at pH 8.5 were also close to the values measured for Ec-NhaA (Table 4). The Vmax values of Vc-NhaA were similar to those of Ec-NhaA, and the Km values of Vc-NhaA both for Na+ (0.65 mM) and Li+ (0.052 mM) were no more than threefold higher than those of Ec-NhaA. We have previously shown that the antiporter activity of Ec-NhaA is strongly dependent on pH, increasing dramatically between pH 7.5 and 8.5 (41). The pH dependence of the Na+/H+ antiporter activity of Vc-NhaA was found to be identical to that of Ec-NhaA (Fig. 2B). A small alkaline shift (of about a 0.5 pH unit) of the pH dependence of the Li+/H+ antiport activity was found (Fig. 2C). Taken together, these results suggest that Vc-NhaA has the potential to play a role in Na+ tolerance in alkaline environments.

FIG. 2.

Na+/H+ antiporter activity of Vc-NhaA. (A) EP432/pBR322-Vc-NhaA or EP432/pGM36 was grown in LBK (pH 7.5), and everted membrane vesicles were isolated. ΔpH was monitored in everted membrane vesicles (50 μg of protein) with acridine orange (0.5 μM) at pH 8.5 in a buffer containing 140 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM BTP. At the onset of the experiment, Tris-d-lactate (2 mM) or ATP (2 mM) was added (arrow pointing down) and the fluorescence quenching (Q) was recorded. NaCl (10 mM, arrows pointing up) was then added, and the new steady state of fluorescence was obtained (dequenching) after each addition was monitored. (B) The pH-dependent Na+/H+ antiport activity of the Vc-NhaA antiporter (closed squares) compared to that of the Ec-NhaA antiporter (opened squares). Membrane vesicles were prepared and assayed as described in the legend to panel A, but the reaction mixtures were titrated to the identical pH with KOH. (C) The pH-dependent Li+/H+ antiport activity of the Vc-NhaA antiporter (closed squares) compared to that of the Ec-NhaA antiporter (open squares).

TABLE 4.

The kinetic parameters of the Vc-NhaA antiporter compared to those of the Ec-NhaA antiportera

| Strain | Chemical and parameter

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na+

|

Li+

|

|||

| Vmax (% dequenching) | Km (mM) | Vmax (% dequenching) | Km (mM) | |

| E. coli NhaA | 86 | 0.2 | 57 | 0.02 |

| V. cholerae NhaA | 94 | 0.65 | 100 | 0.052 |

The kinetic parameters of the antiporter activity were measured in everted membrane vesicles of EP432/pBR322 Vc-nhaA or EP432/pBR322 Ec-nhaA prepared and assayed as described in the legend to Fig. 2A.

To test the antiporter activity of Vc-NhaB, we first used membrane vesicles from EP432/pBR322Vc-NhaB grown in the absence of added Na+. In one experiment, a low Na+/H+ antiporter activity was measured at pH 7.5, but for an unknown reason this result could not be reproduced. Since Vc-NhaB was found to confer Na+ resistance upon KNabc/pBR322Vc-NhaB grown in the presence of 0.2 M NaCl at pH 7.0. (Table 2), we also prepared membrane vesicles from bacteria grown in the presence of 0.2 M Na+ and used strain KNabc/pEL24(Ec-nhaB) as a positive control. Whereas no activity of the Vc-NhaB antiporter was observed in the presence of NaCl or LiCl, Ec-NhaB showed, as previously described (30), a very high antiport activity (data not shown). We suggest that Vc-NhaB, when expressed in the heterologous membranes, is unstable during preparation.

Contribution of Na+/H+ antiporters to the survival of V. cholerae in a saline environment during stationary growth phase.

We have previously characterized the logarithmic growth phenotype of a Vc-nhaA mutant (44) and found that, as opposed to the primary role played by Ec-NhaA in pH and Na+ homeostasis in E. coli, inactivation of Vc-NhaA confers Li+ but not Na+ resistance to logarithmic cells of V. cholerae (44). Here we found that Vc-NhaA expressed in E. coli membranes is very active and similar to that of Ec-NhaA both in kinetic parameters and pH regulation. The assumption that Vc-NhaA is as active in its native membrane as in E. coli membranes led us to investigate further the physiological role of Vc-NhaA under various stress conditions for the pathogen pertaining to Na+ and pH. In parallel we studied the role of the antiporters Vc-NhaB and Vc-NhaD on their own and in combination with Vc-NhaA.

To study the role of Vc-NhaB and Vc-NhaD in V. cholerae, we constructed a Vc-nhaB-disrupted mutant (designated NB) and an nhaD-disrupted mutant (designated ND) from V. cholerae O1 N18 strain. Then we constructed a series of the following double and triple mutants: Vc-nhaAB, Vc-nhaBD, Vc-nhaAD, or Vc-nhaABD mutants (designated NAB, NBD, NAD, and NABD, respectively). Exponential growth of the mutants was followed in nutrient broth at pH 8.5 in the presence of various concentrations of NaCl (0.12 to 1.0 M), LiCl (0.05 to 0.2 M), or KCl (0.12 M). In the presence of either NaCl or KCl, no significant difference in the exponential growth rate was observed between the wild-type strain and the Vc-nhaA, Vc-nhaB, Vc-nhaD, Vc-nhaAB, Vc-nhaAD, Vc-nhaBD, and Vc-nhaABD mutants (data not shown). However, bacterial growth of the Vc-nhaAB, Vc-nhaAD, and Vc-nhaABD mutants was inhibited by 120 mM LiCl at pH 8.5, as described previously for a Vc-nhaA mutant (44). These results are also in marked contrast to those obtained with E. coli, where a mutant inactivated in the two antiporters (Ec-nhaAB) is more susceptible to NaCl than either of the single mutants Ec-nhaA or Ec-nhaB (30).

We have previously found that, in addition to its essential role in pH and Na+ homeostasis during logarithmic growth, Ec-NhaA plays a primary role in the survival of E. coli in the stationary phase (7). We therefore studied the role of the V. cholerae antiporters during the stationary growth phase of V. cholerae by comparing the survival of the wild-type bacteria N18 to NA, NB, ND, and NABD mutants in LB liquid medium in the presence of various Na+ concentrations at different pHs. Following the exponential phase of growth in both LB and LBK media, all strains except ND did not lyse and reached a stationary phase at approximately 109 CFU/ml, which lasted at least up to 16 h of preincubation (data not shown). On the other hand, ND lysed after about 12 h of preincubation. We therefore could not measure its survival during the stationary phase.

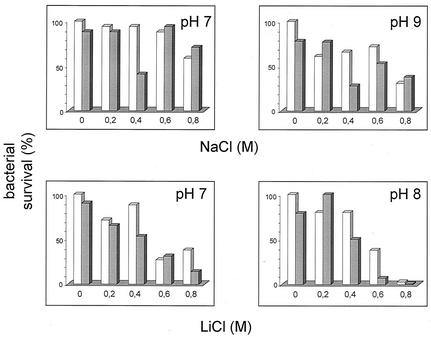

The NA, NB, and NABD stationary-phase bacteria (between 12 to 16 h incubation in LBK) were exposed for 3 h to various stress conditions of pH and salts, and their survival was determined. In the presence of NaCl or LiCl we did not find any significant difference between the wild-type N18 and the single mutants NA and NB (data not shown). However, in the presence of NaCl we found a slight decrease in the survival of the nhaABD mutant (∼50%) compared to that of wild-type N18, but only for a concentration of 0.4 M at pH 7.0 and 9.0 (Fig. 3). This slight decrease was very reproducible and disappeared at concentrations of 0.6 to 0.8 M, presumably due to a compensatory mechanism(s). In the presence of LiCl, a significant difference in survival of the NABD mutant was observed at pH 7.0 in 0.8 M LiCl and pH 8.0 in 0.6 M LiCl. Hence, inactivation of three antiporters instead of one enhanced the salt susceptibility of the N18 strain. These results strongly suggest that the Na+/H+ antiporters contribute to the survival of V. cholerae in a saline environment during the stationary growth phase. However, their conferred resistance to Na+ stress is much less pronounced compared to that of the Li+ stress, a situation that was previously found in the exponential phase of growth (44).

FIG. 3.

The role of V. cholerae antiporters in the stationary phase. N18 (open bars) or NABD mutant (closed bars) was grown for 16 h on LBK-BTP medium and was exposed for 3 h to the indicated pHs and various concentrations of NaCl or LiCl (0.2 to 0.8 M). Bacteria were then plated on LBK agar to determine CFU counts.

Contribution of Vc-NhaA to Na+ resistance of V. cholerae is revealed upon inhibition of the Vc-NQR Na+ pump.

Similar to V. alginolyticus, V. cholerae possesses an electron transport-linked Na+ pump, the NQR pump (12), which specifically extrudes Na+ but not Li+ (13). This Na+-specific activity of the pump may explain the higher contribution observed here of the V. cholerae Na+/H+ antiporters to Li+ resistance compared to that of Na+ resistance. In the absence of Na+/H+ antiporters, the NQR pump can compensate for the Na+/H+ but not Li+/H+ antiport activity, resulting in a Li+-sensitive but not Na+-sensitive phenotype.

To test this possibility, we used NQNO, a quinone analogue similar to that previously shown to inhibit the NQR from V. alginolyticus (43). The results show that 12.5 μM NQNO (Table 5) as well as 25 μM NQNO (data not shown) have no effect on the growth of wild-type V. cholerae. However, as little as 12.5 μM NQNO dramatically inhibited to the same extent the growth of both NA and NABD mutants. These results strongly suggest that NhaA is involved in the Na+ and H+ homeostasis of V. cholerae at alkaline conditions, but its contribution can only be revealed when the Na+ pump activity of NQR is inhibited. Our results show that to understand the Na+ resistance of the V. cholerae pathogen, it is essential to study the interrelationship between the Na+/H+ antiporters and the NQR Na+ pump, both contributing to the Na+ cycle of V. cholerae.

TABLE 5.

Effect of NQNO on growth of wild-type V. cholerae and the mutants NABD and NAa

| V. cholerae strain | Growth (CFU) with or without NQNO at the indicated time (h)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0

|

3

|

10

|

||||

| − | + | − | + | − | + | |

| O1 | 8.0 × 106 | 1.2 × 107 | 8.0 × 108 | 8.0 × 108 | 2.4 × 109 | 2.4 × 109 |

| NABD | 1.6 × 107 | 6.0 × 106 | 1.2 × 109 | 1.2 × 108 | 3.4 × 109 | 2.0 × 108 |

| NA | 1.4 × 107 | 1.2 × 107 | 8.0 × 108 | 6.0 × 107 | 3.4 × 109 | 2.4 × 108 |

Bacteria were grown overnight in LB broth and were diluted 1:500 into LB-BTP (pH 9.0) with or without NQNO (12.5 μM) prepared in ethanol. Serial dilutions were plated on LB plates after 0, 3, and 10 h of incubation.

The sequence analysis of the complete genome of V. cholerae (14) suggests the presence of three other putative antiporters: (i) YqkI, with 57% peptide identity with the Bacillus subtilis antiporter YqkI (48), 27% identity with its paralog YheL (46), and 31% identity with Bacillus firmus NhaC; (ii) NhaP, with 58% identity with NhaP of P. multocida, 40% with NhaP of P. aeruginosa, and 22% with NhaG of B. subtilis; and (iii) NhaC-1 (or NhaC-like), with 36 and 32% identity with NhaC-1 and NhaC-2, respectively, of Borrelia burgdorferi and 16% with the NhaC antiporter of B. firmus. It will be interesting to explore the contribution of these antiporters to the resistance of V. cholerae to various Na+ and pH stress conditions.

Finally, survival of V. cholerae in the saline environment is intimately related to the Na+ cycle, pH, and growth phase conditions. For example, it has been demonstrated that the bacterial number of epidemic V. cholerae O1 is closely related to the salinity and the temperature of water in two estuaries of Florida (15). Our results contribute to the understanding of the molecular mechanisms of persistence of V. cholerae in endemic foci and of the reemergence of new epidemics of cholera.

Acknowledgments

We thank Shamila Nair for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript. Thanks are also due to the Massimo and Adelina Della Pergolla Chair in Life Sciences and the Moshe Shilo Center for Biogeochemistry. We thank T. Tsuchiya for his gift of E. coli TG1 and the KNabc mutant strain and D. Mazel for the E. coli mutant strain β2155.

This work was supported by INSERM and the University of Paris V. It was also supported by the GIF (the German-Israeli Foundation of Scientific Research and Development), The Israeli Science Foundation, and the BMBF and the International Bureau of the BMBF at the DLR (German-Israeli Projects, DIP) (to E.P.).

Katia Herz and Sophie Vimont contributed equally to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barua, D., and M. Merson. 1992. Prevention and control of cholera, p. 329-349. In D. Barua and W. B. Greenough III (ed.), Cholera. Plenum Medical Book Co., New York, N.Y.

- 2.Berche, P., C. Poyart, E. Abachin, H. Lelievre, J. Vandepitte, A. Dodin, and J. M. Fournier. 1994. The novel epidemic strain O139 is closely related to the pandemic strain O1 of Vibrio cholerae. J. Infect. Dis. 170:701-704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brau, B., U. Pilz, and W. Piepersberg. 1984. Genes for gentamicin-(3)-N-acetyltransferases III and IV. I. Nucleotide sequence of the AAC(3)-IV gene and possible involvement of an IS140 element in its expression. Mol. Gen. Genet. 193:179-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colwell, R. R. 1996. Global climate and infectious disease: the cholera paradigm. Science 274:2025-2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colwell, R. R., and A. Huq. 1994. Vibrios in the environment: viable but nonculturable Vibrio cholerae, p. 117-133. In I. K. Wachsmuth, P. A. Blake, and O. Olsvik (ed.), Vibrio cholerae and cholera: molecular to global perspectives. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 6.Donnenberg, M. S., and J. B. Kaper. 1991. Construction of an eae deletion mutant of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli by using a positive-selection suicide vector. Infect. Immun. 59:4310-4317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dover, N., and E. Padan. 2001. Transcription of nhaA, the main Na+/H+ antiporter of Escherichia coli, is regulated by Na+ and growth phase. J. Bacteriol. 183:644-653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dzioba, J., E. Ostroumov, A. Winogrodzki, and P. Dibrov. 2002. Cloning, functional expression in Escherichia coli and primary characterization of a new Na+/H+ antiporter, NhaD, of Vibrio cholerae. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 229:119-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Enomoto, H., T. Unemoto, M. Nishibuchi, E. Padan, and T. Nakamura. 1998. Topological study of Vibrio alginolyticus NhaB Na+/H+ antiporter using gene fusions in Escherichia coli cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1370:77-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faruque, S. M., M. J. Albert, and J. J. Mekalanos. 1998. Epidemiology, genetics, and ecology of toxigenic Vibrio cholerae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:1301-1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldberg, E. B., T. Arbel, J. Chen, R. Karpel, G. A. Mackie, S. Schuldiner, and E. Padan. 1987. Characterization of a Na+/H+ antiporter gene of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:2615-2619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hase, C. C., and B. Barquera. 2001. Role of sodium bioenergetics in Vibrio cholerae. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1505:169-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hase, C. C., N. D. Fedorova, M. Y. Galperin, and P. A. Dibrov. 2001. Sodium ion cycle in bacterial pathogens: evidence from cross-genome comparisons. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 65:353-370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heidelberg, J. F., J. A. Eisen, W. C. Nelson, R. A. Clayton, M. L. Gwinn, R. J. Dodson, D. H. Haft, E. K. Hickey, J. D. Peterson, L. Umayam, S. R. Gill, K. E. Nelson, T. D. Read, H. Tettelin, D. Richardson, M. D. Ermolaeva, J. Vamathevan, S. Bass, H. Qin, I. Dragoi, P. Sellers, L. McDonald, T. Utterback, R. D. Fleishmann, W. C. Nierman, and O. White. 2000. DNA sequence of both chromosomes of the cholera pathogen Vibrio cholerae. Nature 406:477-483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hood, M. A., G. E. Ness, G. E. Rodrick, and N. J. Black. 1983. Distribution of Vibrio cholerae in two Florida estuaries. Microb. Ecol. 9:65-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inaba, M., A. Sakamoto, and N. Murata. 2001. Functional expression in Escherichia coli of low-affinity and high-affinity Na+ (Li+)/H+ antiporters of Synechocystis. J. Bacteriol. 183:1376-1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ivey, D. M., A. A. Guffanti, J. Zemsky, E. Pinner, R. Karpel, E. Padan, S. Schuldiner, and T. A. Krulwich. 1993. Cloning and characterization of a putative Ca2+/H+ antiporter gene from Escherichia coli upon functional complementation of Na+/H+ antiporter-deficient strains by the overexpressed gene. J. Biol. Chem. 268:11296-11303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karpel, R., Y. Olami, D. Taglicht, S. Schuldiner, and E. Padan. 1988. Sequencing of the gene ant which affects the Na+/H+ antiporter activity in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 263:10408-10414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuroda, T., T. Shimamoto, K. Inaba, M. Tsuda, and T. Tsuchiya. 1994. Properties and sequence of the NhaA Na+/H+ antiporter of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 116:1030-1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Majernik, A., G. Gottschalk, and R. Daniel. 2001. Screening of environmental DNA libraries for the presence of genes conferring Na+(Li+)/H+ antiporter activity on Escherichia coli: characterization of the recovered genes and the corresponding gene products. J. Bacteriol. 183:6645-6653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller, C. J., B. S. Drasar, and R. G. Feachem. 1984. Response of toxigenic Vibrio cholerae 01 to physico-chemical stresses in aquatic environments. J. Hyg. (London) 93:475-495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller, V. L., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1988. A novel suicide vector and its use in construction of insertion mutations: osmoregulation of outer membrane proteins and virulence determinants in Vibrio cholerae requires toxR. J. Bacteriol. 170:2575-2583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakamura, T., H. Enomoto, and T. Unemoto. 1996. Cloning and sequencing of the nhaB gene encoding an Na+/H+ antiporter from Vibrio alginolyticus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1275:157-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakamura, T., Y. Fujisaki, H. Enomoto, Y. Nakayama, T. Takabe, N. Yamaguchi, and N. Uozumi. 2001. Residue aspartate-147 from the third transmembrane region of Na+/H+ antiporter NhaB of Vibrio alginolyticus plays a role in its activity. J. Bacteriol. 183:5762-5767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakamura, T., Y. Komano, E. Itaya, K. Tsukamoto, T. Tsuchiya, and T. Unemoto. 1994. Cloning and sequencing of an Na+/H+ antiporter gene from the marine bacterium Vibrio alginolyticus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1190:465-468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nozaki, K., K. Inaba, T. Kuroda, M. Tsuda, and T. Tsuchiya. 1996. Cloning and sequencing of the gene for Na+/H+ antiporter of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 222:774-779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nozaki, K., T. Kuroda, T. Mizushima, and T. Tsuchiya. 1998. A new Na+/H+ antiporter, NhaD, of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1369:213-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Padan, E., N. Maisler, D. Taglicht, R. Karpel, and S. Schuldiner. 1989. Deletion of ant in Escherichia coli reveals its function in adaptation to high salinity and an alternative Na+/H+ antiporter system(s). J. Biol. Chem. 264:20297-20302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Padan, E., D. Zilberstein, and S. Schuldiner. 1981. pH homeostasis in bacteria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 650:151-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pinner, E., Y. Kotler, E. Padan, and S. Schuldiner. 1993. Physiological role of NhaB, a specific Na+/H+ antiporter in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 268:1729-1734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pinner, E., E. Padan, and S. Schuldiner. 1995. Amiloride and harmaline are potent inhibitors of NhaB, a Na+/H+ antiporter from Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 365:18-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pinner, E., E. Padan, and S. Schuldiner. 1992. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of the nhaB gene, encoding a Na+/H+ antiporter in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 267:11064-11068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pinner, E., E. Padan, and S. Schuldiner. 1994. Kinetic properties of NhaB, a Na+/H+ antiporter from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 269:26274-26279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rahav-Manor, O., O. Carmel, R. Karpel, D. Taglicht, G. Glaser, S. Schuldiner, and E. Padan. 1992. NhaR, a protein homologous to a family of bacterial regulatory proteins (LysR), regulates nhaA, the sodium proton antiporter gene in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 267:10433-10438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosen, B. P. 1986. Ion extrusion systems in Escherichia coli. Methods Enzymol. 125:328-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rowe-Magnus, D. A., A. M. Guerout, P. Ploncard, B. Dychinco, J. Davies, and D. Mazel. 2001. The evolutionary history of chromosomal super-integrons provides an ancestry for multiresistant integrons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:652-657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sakasaki, R. 1992. Bacteriology of Vibrio and related organisms, p. 37-55. In D. Barua and W. B. Greenough III (ed.), Cholera. Plenum Medical Book Company, New York, N.Y.

- 38.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 39.Shimada, T., E. Arakawa, K. Itoh, T. Nakazato, T. Okitsu, S. Yamai, M. Kusum, G. B. Nair, and Y. Takeda. 1994. Two strains of Vibrio cholerae non-O1 possessing somatic O antigen factors in common with Vibrio cholerae serogroup O139 synonym Bengal. Curr. Microbiol. 29:331-333. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stewart, G. S., S. Lubinsky-Mink, C. G. Jackson, A. Cassel, and J. Kuhn. 1986. pHG165: a pBR322 copy number derivative of pUC8 for cloning and expression. Plasmid 15:172-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taglicht, D., E. Padan, and S. Schuldiner. 1991. Overproduction and purification of a functional Na+/H+ antiporter coded by nhaA (ant) from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 266:11289-11294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takeshita, S., M. Sato, M. Toba, W. Masahashi, and T. Hashimoto-Gotoh. 1987. High-copy-number and low-copy-number plasmid vectors for lacZ alpha-complementation and chloramphenicol- or kanamycin-resistance selection. Gene 61:63-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tokuda, H., and T. Unemoto. 1982. Characterization of the respiration-dependent Na+ pump in the marine bacterium Vibrio alginolyticus. J. Biol. Chem. 257:10007-10014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vimont, S., and P. Berche. 2000. NhaA, an Na+/H+ antiporter involved in environmental survival of Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 182:2937-2944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Waditee, R., T. Hibino, T. Nakamura, A. Incharoensakdi, and T. Takabe. 2002. Overexpression of a Na+/H+ antiporter confers salt tolerance on a freshwater cyanobacterium, making it capable of growth in sea water. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:4109-4114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang, W., A. A. Guffanti, Y. Wei, M. Ito, and T. A. Krulwich. 2000. Two types of Bacillus subtilis tetA(L) deletion strains reveal the physiological importance of TetA(L) in K+ acquisition as well as in Na+, alkali, and tetracycline resistance. J. Bacteriol. 182:2088-2095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Watson, N. 1988. A new revision of the sequence of plasmid pBR322. Gene. 70:399-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wei, Y., A. A. Guffanti, M. Ito, and T. A. Krulwich. 2000. Bacillus subtilis YqkI is a novel Malic/Na+-lactate antiporter that enhances growth on malate at low protonmotive force. J. Biol. Chem. 275:30287-30292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Williams, S. G., O. Carmel-Harel, and P. A. Manning. 1998. A functional homolog of Escherichia coli NhaR in Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 180:762-765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zor, T., and Z. Selinger. 1996. Linearization of the Bradford protein assay increases its sensitivity: theoretical and experimental studies. Anal. Biochem. 236:302-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]