Abstract

Recent studies demonstrated that 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl 1,2-dioxygenase from Burkholderia sp. strain LB400 (DHBDLB400; EC 1.13.11.39) cleaves chlorinated 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyls (DHBs) less specifically than unchlorinated DHB and is competitively inhibited by 2′,6′-dichloro-2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl (2′,6′-diCl DHB). To determine whether these are general characteristics of DHBDs, we characterized DHBDP6-I and DHBDP6-III, two evolutionarily divergent isozymes from Rhodococcus globerulus strain P6, another good polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) degrader. In contrast to DHBDLB400, both rhodococcal enzymes had higher specificities for some chlorinated DHBs in air-saturated buffer. Thus, DHBDP6-I cleaved the DHBs in the following order of specificity: 6-Cl DHB > 3′-Cl DHB ∼ DHB ∼ 4′-Cl DHB > 2′-Cl DHB > 4-Cl DHB > 5-Cl DHB. It also cleaved its preferred substrate, 6-Cl DHB, three times more specifically than DHB. Interestingly, some of the worst substrates for DHBDP6-I were among the best for DHBDP6-III (4-Cl DHB > 5-Cl DHB ∼ 6-Cl DHB ∼ 3′-Cl DHB > DHB > 2′-Cl DHB ∼ 4′-Cl DHB; DHBDP6-III cleaved 4-Cl DHB two times more specifically than DHB). Generally, each of the monochlorinated DHBs inactivated the enzymes more rapidly than DHB. The exceptions were 4-Cl DHB for DHBDP6-I and 2′-Cl DHB for DHBDP6-III. As observed in DHBDLB400, chloro substituents influenced the reactivity of the dioxygenases with O2. For example, the apparent specificities of DHBDP6-I and DHBDP6-III for O2 in the presence of 2′-Cl DHB were lower than those in the presence of DHB by factors of >60 and 4, respectively. DHBDP6-I and DHBDP6-III shared the relative inability of DHBDLB400 to cleave 2′,6′-diCl DHB (apparent catalytic constants of 0.088 ± 0.004 and 0.069 ± 0.002 s−1, respectively). However, these isozymes had remarkably different apparent Km values for this compound (0.007 ± 0.001, 0.14 ± 0.01, and 3.9 ± 0.4 μM for DHBDLB400, DHBDP6-I, and DHBDP6-III, respectively). The markedly different reactivities of DHBDP6-I and DHBDP6-III with chlorinated DHBs undoubtedly contribute to the PCB-degrading activity of R. globerulus P6.

The microbial degradation of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) has been intensively studied as a possible means to destroy these toxic, persistent environmental pollutants. Particular attention has focused on the bph pathway, which is responsible for the aerobic degradation of biphenyl in a wide range of microorganisms (1, 21). The upper bph pathway consists of four enzymatic activities which together transform biphenyl to benzoate and 2-hydroxypenta-2,4-dienoate. These enzymes also transform some of the approximately 100 different congeners of chlorinated biphenyl that can occur in commercial mixtures of PCBs. The range of PCBs that is transformed by the bph pathway is highly dependent upon the bacterial strain. For example, Burkholderia sp. strain LB400 (Burkholderia sp. strain LB400 was originally identified as Pseudomonas sp. strain LB400 [13]) and Rhodococcus globerulus strain P6 (R. globerulus strain P6 has variously been identified as Acinetobacter sp. strain P6, Corynebacterium sp. strain MB1, and Arthrobacter sp. strain M5 [7, 22]) transform exceptionally broad, but different, ranges of PCBs, including some hexachlorinated congeners (13, 29). Burkholderia sp. strain LB400 transforms ortho-chlorinated or non-dioxin-like congeners relatively well. In contrast, R. globerulus P6 preferentially transforms more coplanar or dioxin-like congeners exemplified by 3,3′-dichloro (3,3′-diCl) and 4,4′-diCl biphenyls (11, 12).

The optimization of microbial catabolic activities for the biodegradation of PCBs necessitates the determination of the specificity of bph pathway enzymes for chlorinated metabolites. PCB transformation has been studied largely as a function of biphenyl dioxygenase, the first enzyme of the bph pathway (for recent examples, see references 10 and 42). A few studies have focused on the second enzyme of the pathway (15, 39). However, its role in PCB degradation remains to be fully elucidated. More recently, the fourth enzyme of the pathway was identified as an important determinant of PCB degradation, being competitively inhibited by some chlorinated metabolites (36, 37).

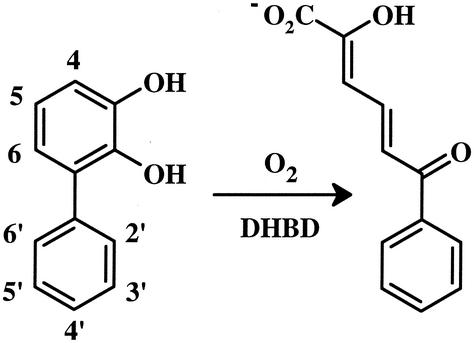

2,3-Dihydroxybiphenyl 1,2-dioxygenase (DHBD; EC 1.13.11.39) is the third enzyme of the bph degradation pathway. This enzyme utilizes a mononuclear nonheme iron(II) center to cleave 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl (DHB) in an extradiol fashion (Fig. 1). Whole-cell studies indicate that DHBD is of particular significance to the degradation of PCBs, as it is incapable of transforming certain chlorinated DHBs (23, 38). Recent studies demonstrated that DHBD from Burkholderia sp. strain LB400 (DHBDLB400) cleaves chlorinated DHBs less specifically than unchlorinated DHB and is competitively inhibited by 2′,6′-diCl DHB (17). DHBD is also inhibited by 3-chlorocatechol (2, 5, 8, 41, 44), a compound that is formed during the degradation of PCBs. In the DHBD-catalyzed reaction, the catechol binds to the enzyme first, activating the active-site Fe(II) for O2 binding (3, 4, 27, 43). During steady-state cleavage, DHBD is subject to two types of inhibition: reversible substrate inhibition and an irreversible mechanism-based inactivation, or suicide inhibition (43). The suicide inhibition of DHBD by DHB and 3-chlorocatechol involves the release of superoxide from the DHBD:DHB:O2 ternary complex and the oxidation of the active-site Fe(II) (44). It is unclear whether the reactivity of DHBDLB400 with PCB metabolites is representative of that of other DHBDs.

FIG. 1.

Reaction catalyzed by DHBD.

R. globerulus strain P6 contains three different enzymes that have been identified as DHBDs based on their abilities to cleave DHB (6, 8). Of the three isozymes, DHBDP6-I, encoded by bphC1, appears to be the functional homologue of DHBDLB400: both are two-domain enzymes (25), sharing 52% sequence identity, and the genes encoding these enzymes occur in the bph operon. The physiological function of DHBDP6-II and DHBDP6-III, encoded by bphC2 and bphC3, respectively, is less clear. These isozymes are single-domain enzymes that share 58% sequence identity with each other and approximately 17% sequence identity with the C-terminal domain of the two-domain enzymes (19, 25). Analysis of the DNA sequence surrounding bphC2 and bphC3 reveals no significant similarity to other bph genes. Gel filtration results indicate that R. globerulus P6 expresses DHBDP6-I and DHBDP6-II and/or DHBDP6-III when grown on biphenyl as the sole carbon source (6). Interestingly, several other gram-positive actinomycetes also possess multiple genes coding for DHBDs (30, 32, 35, 40). Most of these organisms are able to transform a wide range of PCBs and other aromatic compounds. However, the relationship between these catabolic capabilities and the occurrence of multiple DHB-cleaving enzymes in a single organism is unclear.

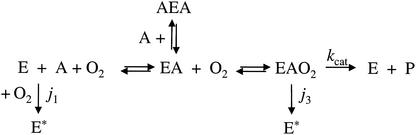

Herein, we report the reactivity of DHBDP6-I and DHBDP6-III towards each of the six monochlorinated DHBs. Steady-state kinetic studies based on the general mechanism of DHBD (Fig. 2) were conducted to determine the apparent specificities of the enzyme for DHBs and O2. The reactivity of these two DHBDs towards the recalcitrant 2′,6′-diCl DHB was also investigated. Finally, the suicide inhibition of these enzymes by each of the DHBs was studied. The results are discussed with respect to the reactivity of DHBDLB400 with these compounds as well as the physiological significance of the occurrence of evolutionarily divergent DHBDs in a single bacterium.

FIG. 2.

General mechanism of DHBD during steady-state turnover. Only DHBDP6-I is subject to substrate inhibition. E* denotes inactivated forms of the enzyme. The rate constants j1 and j3 are associated with reactions that result in enzyme inactivation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

DHB, 4-Cl DHB, 5-Cl DHB, 6-Cl DHB, 2′-Cl DHB, 3′-Cl DHB, 4′-Cl DHB, and 2′,6′-diCl DHB were synthesized according to standard procedures (33) and were a gift from Victor Snieckus. Ferene S was from ICN Biomedicals, Inc. (Costa Mesa, Calif.). All other chemicals were of analytical grade and used without further purification.

Strains, media, and growth.

Chromosomal DNA of R. globerulus strain P6 was a kind gift from Michel Sylvestre. Escherichia coli strain DH5α was used for DNA propagation and was cultured at 37°C and 200 rpm in Luria-Bertani broth with the appropriate antibiotics. Pseudomonas putida strain KT2442 (26), transformed with pVLT31 (18) derivatives, was used for overexpression and was cultured at 30°C and 250 rpm in Luria-Bertani broth with 20 μg of tetracycline/ml supplemented with phosphate buffer and mineral salts as previously described (43).

Construction of plasmids and overexpression of protein.

DNA was purified, restricted, ligated, and transformed according to standard protocols (9). The bphC1 and bphC3 genes were amplified by PCR from the chromosomal DNA of R. globerulus strain P6 that had been partially digested with BamHI. The bphC1 gene was amplified with two primers: C1for (5′-GCGCCATGGGTGTTCAGCGACTGGGTT-3′), which introduces an NcoI site (underlined) at the beginning of the bphC1 gene and modifies the second codon (Ser→Gly), and C1rev (5′-CCGCTGCAGGCCCTTACTCTCCC-3′), which introduces a PstI site (underlined) after the stop codon of the bphC1 gene. The bphC3 gene was amplified with two other primers: C3for (5′-GCCCCATGGCCGTCACACCGCGCCTTG-3′), which introduces an NcoI site (underlined) at the start of the bphC3 gene and modifies the second codon (Thr→Ala), and C3rev (5′-CGGCTGCAGATCAGGGGGTCAG-3′), which introduces a PstI site (underlined) after the stop codon of the bphC3 gene. PCRs were performed by using Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's instructions and an oligonucleotide hybridization step at 48°C. The resulting DNA fragments were digested with NcoI and PstI and cloned in pLEHP20 (20), yielding the expression plasmids pHMC1-1 and pHMC3-1 for bphC1 and bphC3, respectively. The genes were sequenced on an ABI 373 Strech (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) apparatus with BigDye terminators to confirm that they contained no errors. Both genes were subcloned using XbaI and PstI into the pVLT31 vector (18), yielding plasmids pHMC1-2 and pHMC3-2, containing bphC1 and bphC3, respectively. DHBDP6-I and DHBDP6-III were overexpressed in P. putida strain KT2442 freshly transformed with pHMC1-2 and pHMC3-2, respectively. The cultures were grown to an optical density at 600 nm of approximately 0.5, at which point 0.25 mM isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside was added to induce expression. The cultures were incubated for an additional 20 h before harvesting.

Protein purification.

All buffers were prepared by using water purified on a Barnstead NANOpure UV apparatus to a resistivity of greater than 17 MΩ×cm. After disruption of the cell preparations, DHBDP6-I and DHBDP6-III were manipulated under an inert atmosphere in an Mbraun (Stratham, N. H.) Labmaster glove box maintained at 2 ppm of O2 or less. Chromatography was performed as previously described (43) on an AKTA Explorer 100 (Amersham Biosciences, Montreal, Quebec, Canada) configured to maintain an anaerobic atmosphere during purification. Buffers were sparged with N2 and equilibrated in the glove box for at least 24 h prior to the addition of t-butanol, dithiothreitol (DTT), and ferrous ammonium sulfate when appropriate.

Cell pellets from 4 and 2 liters of culture were resuspended in 10 mM Tris, pH 7.5, for DHBDP6-I and DHBDP6-III, respectively. The cells were disrupted by two successive passages through a French press operated at 12,500 lb/in2 and 4°C. The cell debris was removed by ultracentrifugation in gas-tight tubes at 180,000 × g for 60 min. The clear supernatant was carefully removed and referred to as the raw extract.

The raw extract containing DHBDP6-I (approximately 17 ml) was divided into four equal portions, each of which was loaded onto an HR 10/10 Mono Q anion exchange column (Amersham Biosciences) equilibrated with buffer A (10 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 10% t-butanol, 2 mM DTT, 0.25 mM ferrous ammonium sulfate). The column was operated at a flow rate of 3.0 ml/min. The enzyme activity was eluted with a 180-ml linear gradient of 20 to 50% buffer B (buffer A containing 1.0 M NaCl). Fractions of 5 ml were collected. DHBDP6-I eluted at approximately 400 mM NaCl, and purity was verified by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (9). Fractions containing activity from the four runs were combined and concentrated in an Amicon stirred cell concentrator (Millipore, Ltd., Nepean, Ontario, Canada) to 25 to 30 mg/ml and flash-frozen as beads in liquid nitrogen.

The raw extract containing DHBDP6-III (approximately 19 ml) was divided into five equal portions, each of which was loaded onto an HR 10/10 Mono Q anion exchange column equilibrated with buffer C (10 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 1 mM DTT, 0.15 mM ferrous ammonium sulfate). The column was operated at a flow rate of 2.5 ml/min. Proteins that were not bound tightly to the resin were eluted with a 30-ml wash of 10% buffer D (buffer C containing 1.0 M NaCl). The enzyme activity was eluted using a 120-ml linear gradient of 10 to 40% buffer D. Fractions of 5 ml were collected. DHBDP6-III eluted at approximately 190 mM NaCl. Fractions containing activity from the five runs were combined and concentrated in an Amicon stirred cell concentrator until the volume reached approximately 10 ml. To this solution, an equal volume of buffer E (buffer C containing 0.82 M ammonium sulfate) was added, and the protein was divided into five equal portions, each of which was loaded on a phenyl-Sepharose column (1 by 10 cm; Amersham Biosciences) equilibrated with 50% buffer E. The column was operated at a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min. Proteins that were not bound tightly to the resin were eluted with a 25-ml wash of 50% buffer E. The enzyme activity was eluted with a 60-ml linear gradient of 50 to 0% buffer E. Fractions of 2.5 ml were collected. DHBDP6-III eluted at approximately 5% buffer E, and purity was verified by SDS-PAGE (9). Fractions containing activity from the five runs were combined, and several steps of concentration and dilution with buffer C were performed in an Amicon stirred cell concentrator until no ammonium sulfate remained. The final protein concentration reached 20 to 25 mg/ml, and the solution was flash-frozen as beads in liquid nitrogen. Preparations of purified DHBDP6-III and DHBDP6-I were stored at −80°C for several months without loss of activity.

Handling of DHBD samples.

Aliquots of DHBD were anaerobically thawed immediately prior to use and exchanged into 20 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazinepropanesulfonic acid (HEPPS)-80 mM NaCl (ionic strength [I] = 0.1), pH 8.0, by gel filtration chromatography (43) unless otherwise stated. Samples of DHBD were further diluted with the same buffer as required.

SDS-PAGE was performed in a Bio-Rad MiniPROTEAN II apparatus, and the gels were stained with Coomassie blue according to established procedures (9). Protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford method (14). Iron concentrations were determined colorimetrically by using Ferene S (24).

Kinetic measurements and analysis of steady-state data.

Enzymatic activity was routinely measured by following the consumption of dioxygen with a Clark-type polarographic O2 electrode (model 5301; Yellow Springs Instruments, Yellow Springs, Ohio) as previously described (43). All experiments were performed with potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0 (I = 0.1), at 25.0 ± 0.1°C unless otherwise stated. The standard activity assay was performed with 80 μM DHB. Concentrations of active DHBD in the assay were defined by the iron content of the injected purified enzyme solution and were used in calculating the specificity, catalytic, and inactivation constants. One unit of enzymatic activity was defined as the quantity of enzyme required to consume 1 μmol of O2 per min. The O2 electrode was calibrated with standard concentrations of DHBD (either DHBDLB400 [43], DHBDP6-I, or DHBDP6-III) and DHB.

For specificity experiments in which the concentration of the DHBs was varied in air-saturated buffer, the initial velocities obtained were fit to an equation describing a mechanism involving substrate inhibition (based on Fig. 2) or to the Michaelis-Menten equation (16), as appropriate. In each case, the substrate concentration and reaction velocities were monitored after the initiation of the reaction (10 to 20 s) and compared to the calculated values to reject assays involving greater than 15% inactivation of the enzyme (43).

The steady-state cleavage of 2′,6′-diCl DHB by DHBD could not be directly followed with the oxygen electrodes due to the very slow rate of catalysis. However, it could be observed spectrophotometrically by following the appearance of product at 391 nm in potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0 (I = 0.1); ɛ = 36.5 mM−1 cm−1. By using the spectrophotometric assay, the apparent catalytic constant kcatapp for 2′,6′-diCl DHB could be determined for both enzymes. The KmAapp of DHBDP6-III for 2′,6′-diCl DHB was also determined by using this assay. The KmAapp of DHBDP6-I for 2′,6′-diCl DHB was determined with DHB as a reporter substrate in the oxygen electrode assay. The concentration of DHB was varied from 3 to 85 μM (i.e., at concentrations below those at which substrate inhibition is observed), and the concentration of 2′,6′-diCl DHB was varied from 0.02 to 1.3 μM. An equation identical in form to that for competitive inhibition was fit to the data (16). In this equation, the KmAapp of 2′,6′-diCl DHB replaces the competitive inhibition constant Kic.

For the O2 specificity experiments, the concentration of monochlorinated DHB was fixed such that the enzyme was saturated (>10 × KmAapp) without substrate inhibition occurring. The assay buffer was equilibrated with gas mixtures containing between 2.5 and 100% O2, as appropriate. Kinetic parameters were calculated from the initial velocities by using the Michaelis-Menten equation. All fitting was performed using the least-squares and dynamic weighting options of LEONORA (16).

Influence of copper on activity.

The influence of Cu(II) on the enzyme activity was tested by incubating DHBDP6-I (0.24 mg/ml) and DHBDP6-III (0.4 mg/ml) anaerobically for 2 min at 0°C in 20 mM HEPPS-80 mM NaCl, pH 8.0, containing various concentrations of CuCl2 · 2H2O prior to initiation of the reaction in the standard assay.

Stability in the presence of O2 and mechanism-based inactivation studies.

The stability of the free enzyme in the presence of O2 was studied by incubating DHBD in the oxygraph cuvette under standard assay conditions and monitoring At, the activity remaining after different time intervals, by adding 150 μM DHB to the cuvette. The apparent first-order rate constant of inactivation j1app was determined as previously described by using equation 1 (44), in which Amax is the activity observed in the absence of preincubation.

|

(1) |

Partition ratios for all substrates except 2′,6′-diCl DHB were determined by an oxygraph assay according to standard procedures (44). For 2′,6′-diCl DHB, the partition ratio was determined spectrophotometrically by using the assay described in the previous section. The amount of DHBD added to the reaction cuvette was such that the enzyme was completely inactivated before 15% of either the catecholic substrate or O2 was consumed in the reaction mixture. The partition ratio was calculated by dividing the amount of product formed by the amount of active DHBD added to the assay.

The apparent rate constant of inactivation during catalytic turnover in air-saturated buffer, j3app, was calculated from the partition ratio determined by using the oxygraph assay under saturating substrate conditions ([S] ≫ Km) according to established procedures (equation 2; [44]) except for 2′,6′-diCl DHB. Under such conditions, the concentration of free enzyme, [E], is negligible and the partition ratio is equal to the ratio of the catalytic constant kcatapp to the inactivation constant j3app (i.e., Σji = j3).

|

(2) |

The rate constant of inactivation, j3app, for 2′,6′-diCl DHB was evaluated from the rate constant of saturation js by using equation 3 (44). The latter was determined from progress curves obtained spectrophotometrically at 391 nm from reactions performed at saturating substrate concentrations [S] (100 to 200 μM) by using equation 4 (44).

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

In equation 3, Kmapp is the apparent Km of 2′,6′-diCl DHB in air-saturated buffer. In equation 4, Pi and P∞ are the concentrations of product at the start and end of the assay, respectively, and Pt is the concentration of product formed after different time intervals.

RESULTS

Purification.

DHBDP6-I and DHBDP6-III were purified anaerobically to apparent homogeneity. Relevant details of the purifications are shown in Table 1. The enzymes were estimated to be greater than 99% pure by SDS-PAGE (data not shown). Total yields of 117 mg of DHBDP6-I and 84 mg of DHBDP6-III were obtained from 4 and 2 liters of cell culture, respectively. Ninefold and fivefold increases in specific activity were observed upon purification for DHBDP6-I and DHBDP6-III, respectively, and the iron content of the purified enzymes was typically higher than 85%.

TABLE 1.

Purification details of DHBDP6-I and DHBDP6-III expressed in P. putida strain KT2442a

| Isozyme and purification step | Total protein (mg) | Total act (U) | Sp act (U/mg) | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DHBDP6-I | ||||

| Raw extract | 1,450 | 19,260 | 14.1 | 100 |

| Mono Q | 117 | 14,320 | 122.6 | 74 |

| DHBDP6-III | ||||

| Raw extract | 834 | 6,570 | 7.9 | 100 |

| Mono Q | 245 | 5,880 | 24.0 | 89 |

| Phenyl-Sepharose | 84 | 3,010 | 36.0 | 46 |

Activity units are defined in Materials and Methods.

Coupling of the reaction and stability in the presence of O2.

The coupling of DHB and O2 utilization in DHBDP6-I and DHBDP6-III was investigated using an O2 electrode that had been calibrated with DHB and DHBDLB400, which constitutes a well-coupled system (43). For each P6 isozyme, the amount of O2 consumed corresponded to the amount of DHB added to the reaction mixture, demonstrating that the utilization of DHB and O2 was tightly coupled in both enzymes.

The stability of each enzyme in the presence of O2 was evaluated by determining j1app, the pseudo-first-order rate constant of inactivation in air-saturated buffer. The respective j1app values of DHBDP6-I and DHBDP6-III were (0.7 ± 0.1) × 10−3 and (4.4 ± 0.5) × 10−3 s−1, which correspond to half-lives of 16.5 ± 2 and 2.6 ± 0.3 min, respectively.

Influence of copper on DHB cleavage activity.

Incubation of DHBDP6-I (0.24 mg/ml) in the presence of 10, 25, 50, 100, 200, and 500 μM copper chloride resulted in 24, 58, 76, 90, 94, and 95% inhibition of the enzyme's DHB cleavage activity, respectively. Similar incubation of DHBDP6-III (0.4 mg/ml) inhibited the cleavage of DHB by 17, 35, 44, 63, 67, and 85%, respectively. Copper was therefore not included in any of the kinetic assays.

Steady-state kinetic analyses.

Steady-state kinetic analyses in which the DHB and O2 concentrations were varied demonstrated that DHBDP6-I and DHBDP6-III utilize a compulsory-order, ternary-complex mechanism (Fig. 2 and data not shown). DHBDP6-I, like DHBDLB400, was subject to substrate inhibition. In contrast, DHBDP6-III was not. Both P6 isozymes, like DHBDLB400, were susceptible to inactivation during the steady-state turnover. Accordingly, the apparent specificities of DHBDP6-I and DHBDP6-III for chloro DHBs (kAapp = kcatapp/KmAapp) and their apparent inactivation (j3app) by these compounds were studied essentially as described previously for DHBDLB400 (44).

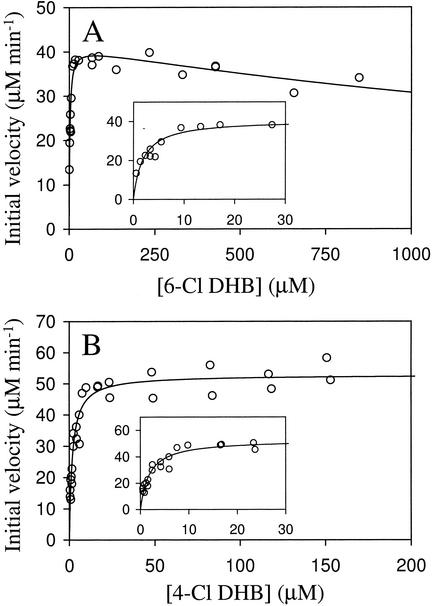

The results of typical steady-state kinetic experiments performed by varying the concentration of monochlorinated DHBs in air-saturated buffer are shown in Fig. 3. Interestingly, DHBDP6-I and DHBDP6-III cleaved some chloro DHBs more specifically than DHB (Table 2). Thus, DHBDP6-I cleaved 6-Cl DHB three times more specifically than DHB and cleaved 3′-Cl DHB, 4′-Cl DHB, and unchlorinated DHB with similar specificity. Overall, DHBDP6-I cleaved monochlorinated DHBs in the following order of specificity: 6-Cl DHB > 3′-Cl DHB ∼ DHB ∼ 4′-Cl DHB > 2′-Cl DHB > 4-Cl DHB > 5-Cl DHB. Similarly, DHBDP6-III cleaved a total of four monochlorinated DHBs more specifically than DHB, showing the highest apparent specificity for 4-Cl DHB in air-saturated buffer. DHBDP6-III cleaved the DHBs in the following order of specificity: 4-Cl DHB > 5-Cl DHB ∼ 6-Cl DHB ∼ 3′-Cl DHB > DHB > 2′-Cl DHB ∼ 4′-Cl DHB. By comparison, DHBDLB400 cleaved monochlorinated DHBs between 0.1 and 0.3 times that of unchlorinated DHB in the following order of specificity: DHB > 4′-Cl DHB > 6-Cl DHB > 3′-Cl DHB > 4-Cl DHB > 5-Cl DHB > 2′-Cl DHB.

FIG. 3.

Steady-state cleavage of 6-Cl DHB by DHBDP6-I and 4-Cl DHB by DHBDP6-III. The experiments were performed using air-saturated potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0 (I = 0.1), at 25°C. (A) DHBDP6-I-catalyzed cleavage of 6-Cl DHB. The line represents a best fit of the substrate inhibition equation to the data. The fitted parameters are KmAapp = 1.9 ± 0.3 μM, KiAapp = 3.0 ± 0.9 mM, and Vmaxapp = 41.1 ± 1.2 μM/min. The inset shows the initial portion of the graph (0 to 30 μM 6-Cl DHB) in more detail. (B) DHBDP6-III-catalyzed cleavage of 4-Cl DHB. The line represents a best fit of the Michaelis-Menten equation to the data. The fitted parameters are KmAapp = 1.8 ± 0.2 μM and v = 52.7 ± 1.2 μM/min. The inset shows the initial portion of the graph (0 to 30 μM 4-Cl DHB) in more detail.

TABLE 2.

Apparent steady-state kinetic parameters and inactivation parameters of DHBDP6-I, DHBDP6-III, and DHBDLB400 for chlorinated DHBsa

| Isozyme and compound | KmAapp (μM) | KiAapp (mM) | kcatapp (s−1) | kAapp (106 M−1 s−1) | Partition ratio | j3app (10−3 s−1) | j3app/KmAapp (103 M−1 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DHBDP6-I | |||||||

| DHB | 5.8 (1.0) | 2.2 (0.7) | 77.5 (2.7) | 13.3 (1.9) | 31,100 (3,300) | 2.5 (0.4) | 0.43 (0.14) |

| 2′-Cl DHB | 0.22 (0.06) | 2.02 (0.04) | 9 (2) | 1,650 (80) | 1.2 (0.1) | 5.5 (2.0) | |

| 3′-Cl DHB | 1.9 (0.3) | 1.5 (0.3) | 27.1 (0.8) | 14.2 (1.8) | 2,300 (200) | 11.8 (1.3) | 6.2 (1.7) |

| 4′-Cl DHB | 2.6 (0.3) | 6.6 (3.4) | 29.1 (0.7) | 11.4 (1.0) | 3,260 (130) | 8.9 (0.6) | 3.5 (0.6) |

| 4-Cl DHB | 22.0 (2.6) | 2.6 (0.7) | 109 (5) | 4.9 (0.4) | 27,800 (200) | 3.9 (0.2) | 0.18 (0.03) |

| 5-Cl DHB | 5.3 (0.6) | 7.2 (0.2) | 1.4 (0.1) | 660 (35) | 11.0 (0.8) | 2.1 (0.4) | |

| 6-Cl DHB | 1.9 (0.3) | 3.0 (0.9) | 72.5 (2.2) | 39 (5) | 4,085 (25) | 17.7 (0.6) | 9.4 (1.8) |

| 2′6′-diCl DHB | 0.144 (0.014) | 0.088 (0.004) | 0.61 (0.09) | 49.9 (1.2) | 1.7 (0.1) | 11.7 (1.6) | |

| DHBDP6-III | |||||||

| DHB | 16.7 (1.9) | 17.0 (0.6) | 1.0 (0.1) | 895 (60) | 19.0 (2.0) | 1.1 (0.2) | |

| 2′-Cl DHB | 10.4 (1.0) | 5.3 (0.1) | 0.51 (0.04) | 1,990 (160) | 2.7 (0.3) | 0.25 (0.05) | |

| 3′-Cl DHB | 10.4 (0.7) | 14.2 (0.3) | 1.36 (0.08) | 870 (70) | 16.3 (1.7) | 1.6 (0.3) | |

| 4′-Cl DHB | 27.0 (3.0) | 12.7 (0.4) | 0.47 (0.04) | 410 (60) | 31.2 (5.5) | 1.2 (0.3) | |

| 4-Cl DHB | 1.8 (0.2) | 4.0 (0.1) | 2.2 (0.2) | 260 (40) | 15.5 (3.0) | 8.6 (2.6) | |

| 5-Cl DHB | 4.3 (0.6) | 6.6 (0.3) | 1.5 (0.2) | 97 (20) | 68.0 (17.1) | 15.8 (6.2) | |

| 6-Cl DHB | 3.9 (0.8) | 5.5 (0.3) | 1.4 (0.2) | 200 (10) | 27.8 (3.1) | 7.1 (2.2) | |

| 2′6′-diCl DHB | 3.9 (0.4) | 0.069 (0.002) | 0.017 (0.001) | 14.8 (0.3) | 5.4 (0.2) | 1.4 (0.1) | |

| DHBDLB400 | |||||||

| DHB | 12 (1) | 2.7 (0.6) | 251 (6) | 21 (1) | 84,900 (1,400) | 3.0 (0.1) | 0.25 (0.10) |

| 2′-Cl DHB | 2.3 (0.2) | 2.7 (0.6) | 5.0 (0.7) | 2.1 (0.2) | 1,390 (150) | 3.6 (0.9) | 1.6 (0.5) |

| 3′-Cl DHB | 58 (5) | 0.40 (0.05) | 305 (19) | 5.3 (0.2) | 42,000 (14,000) | 7.3 (2.9) | 0.13 (0.06) |

| 4′-Cl DHB | 68 (11) | 0.38 (0.07) | 430 (50) | 6.4 (0.4) | 40,600 (5,500) | 10.6 (2.7) | 0.16 (0.07) |

| 4-Cl DHB | 23 (1) | 72 (1) | 3.1 (0.1) | 10,850 (400) | 6.6 (0.3) | 0.29 (0.06) | |

| 5-Cl DHB | 26.4 (3.1) | 2.5 (0.7) | 63 (3) | 2.4 (0.2) | 12,000 (1,500) | 5.2 (0.9) | 0.20 (0.06) |

| 6-Cl DHB | 6.5 (0.6) | 1.28 (0.15) | 38.3 (0.9) | 5.9 (0.4) | 5,500 (470) | 7.0 (0.8) | 1.1 (0.2) |

| 2′6′-diCl DHB | 0.007 (0.001) | 0.036 (0.001) | 5.1 (0.9) | 49.5 (1.6) | 0.69 (0.01) | 99 (16) |

Experiments with DHBDP6-I and DHBDP6-III were performed using air-saturated potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0 (I = 0.1), at 25°C. KmAapp, KiAapp, kcatapp, kAapp, and j3app represent the apparent Km, inhibition constant, catalytic constant, specificity constant, and rate constant of inactivation during catalytic turnover, respectively, for DHB or chloro DHBs. All DHBDLB400 data except KiAapp were either taken or extrapolated from Dai et al. (17). Values in parentheses represent standard errors.

The apparent specificities of the two P6 isozymes for O2 were studied at saturating concentrations of DHB and each of the six monochlorinated DHBs (Table 3). The apparent specificity constant of both DHBDP6-I and DHBDP6-III for O2 (kBapp = kcatapp/KmBapp) was highest in the presence of DHB. In contrast, the kB of DHBDLB400 was highest in the presence of 3′-Cl DHB and 4′-Cl DHB (17). Moreover, chlorinated DHBs influenced the respective reactivities of DHBDP6-I and DHBDP6-III with O2 in different ways. For example, the KmBapp of DHBDP6-I was lowest in the presence of 4′-Cl DHB whereas that of DHBDP6-III was highest in the presence of this same compound. Nevertheless, the lowest kBapp value of both isozymes was observed in the presence of 2′-Cl DHB, the most slowly cleaved substrate. However, the decrease in specificity versus that observed in the presence of DHB was more drastic for DHBDP6-I (>60-fold) than for DHBDP6-III (3.6-fold). In comparison, the kB of DHBDLB400 was 50-fold lower in the presence of 2′-Cl DHB than in the presence of DHB (17).

TABLE 3.

Apparent steady-state kinetic parameters of DHBDP6-I and DHBDP6-III for O2 in the presence of monochlorinated DHBsa

| Isozyme and compound | Concn of (Cl-) DHB (μM) | KmBapp (μM) | kcatapp (s−1) | kBapp (106 M−1 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DHBDP6-I | ||||

| DHB | 275 | 253 (16) | 121 (4) | 0.48 (0.02) |

| 2′-Cl DHB | 35 | >5,000 | ∼40 | <0.008 |

| 3′-Cl DHB | 150 | 240 (16) | 32 (1) | 0.134 (0.005) |

| 4′-Cl DHB | 150 | 167 (4) | 32.1 (0.4) | 0.193 (0.003) |

| 4-Cl DHB | 750 | 750 (120) | 200 (16) | 0.269 (0.022) |

| 5-Cl DHB | 250 | 334 (52) | 10.7 (0.8) | 0.032 (0.003) |

| 6-Cl DHB | 150 | 425 (28) | 103 (4) | 0.243 (0.008) |

| DHBDP6-III | ||||

| DHB | 270 | 480 (80) | 45.6 (3.5) | 0.095 (0.009) |

| 2′-Cl DHB | 200 | 700 (150) | 18.0 (1.8) | 0.026 (0.003) |

| 3′-Cl DHB | 200 | 387 (50) | 26.1 (1.3) | 0.067 (0.006) |

| 4′-Cl DHB | 350 | 726 (82) | 43.5 (2.8) | 0.060 (0.003) |

| 4-Cl DHB | 85 | 116 (17) | 5.0 (0.2) | 0.044 (0.005) |

| 5-Cl DHB | 55 | 619 (100) | 19.0 (1.4) | 0.031 (0.003) |

| 6-Cl DHB | 70 | 440 (120) | 15.7 (1.6) | 0.036 (0.006) |

Experiments were performed with potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0 (I = 0.1), at 25°C with saturating, but noninhibiting, concentrations of (monochlorinated) DHBs. KmBapp, kcatapp, kBapp represent the apparent Km, catalytic constant, and specificity constant, respectively, for O2 in the presence of DHM or chloro DHBs. Values in parentheses represent standard errors.

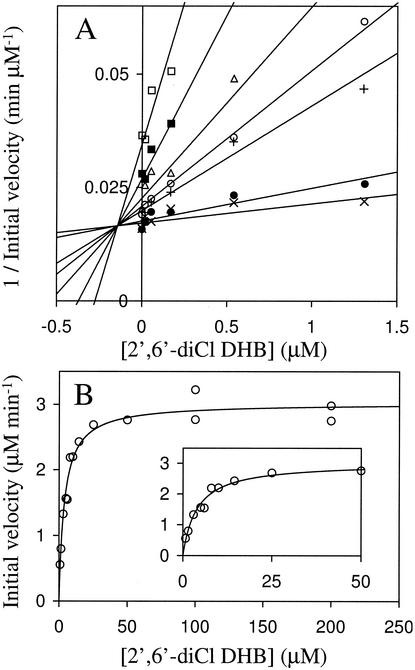

As with DHBDLB400, the cleavage of 2′,6′-diCl DHB by DHBDP6-I and DHBDP6-III was too slow to follow directly with the oxygen electrodes. By using a spectrophotometric assay to follow product formation, the KmAapp of DHBDP6-III for 2′,6′-diCl DHB was 3.9 ± 0.4 μM (Fig. 4). The KmAapp of DHBDP6-I for 2′,6′-diCl DHB could not be determined by this assay due to the very low KmAapp of the enzyme for this compound. By using DHB as a reporter substrate in the oxygen electrode assay, 2′,6′-diCl DHB competitively inhibited the cleavage of DHB by DHBDP6-I with a Kicapp of 0.144 ± 0.014 μM in air-saturated buffer (Fig. 4). By using the same assay, 2′,6′-diCl DHB competitively inhibited the cleavage of DHB by DHBDP6-III with a Kicapp of 2.6 ± 0.2 μM, confirming the spectrophotometrically determined value. Under saturating substrate conditions, 2′,6′-diCl DHB was cleaved 900 and 250 times slower than DHB by DHBDP6-I and DHBDP6-III, respectively (Table 2).

FIG. 4.

Steady-state utilization of 2′,6′-diCl DHB by DHBDP6-I and DHBDP6-III. The experiments were performed using air-saturated potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0 (I = 0.1), at 25°C. (A) DHBDP6-I-catalyzed cleavage of DHB in the presence of 2′,6′-diCl DHB. The rate of DHB cleavage was determined by using 3.1 μM (□), 5.4 μM (▪), 9.3 μM (▵), 13.1 μM (○), 16.9 μM (+), 54 μM (•), and 82.9 μM (×) DHB. Fits were obtained using an equation similar in form to that describing competitive inhibition as described in Materials and Methods. The fit of the equation to the data yielded the following parameters: KmAapp = 0.144 ± 0.014 μM, KmDHBapp = 3.4 ± 0.3 μM, and Vmaxapp = 60.4 ± 1.5 μM/min. (B) The DHBDP6-III-catalyzed cleavage of 2′,6′-diCl DHB. The line represents a best fit of the Michaelis-Menten equation to the data. The fitted parameters are Kmaxapp = 3.9 ± 0.4 μM and Vmaxapp = 3.0 ± 0.1 μM/min. The inset shows the initial portion of the graph (0 to 50 μM 2′,6′-diCl DHB) in more detail.

The DHBD isozymes had different susceptibilities to inactivation (j3app/KmAapp) by the chlorinated substrates. Thus, DHBDP6-I was inactivated by these compounds in the following order: 2′,6′-diCl DHB > 6-Cl DHB > 3′-Cl DHB > 2′-Cl DHB > 4′-Cl DHB > 5-Cl DHB > DHB > 4-Cl DHB. In contrast, DHBDP6-III was inactivated by these compounds in the following order: 5-Cl DHB > 4-Cl DHB > 6-Cl DHB > 3′-Cl DHB > 2′,6′-diCl DHB > 4′-Cl DHB > DHB > 2′-Cl DHB. These patterns differ from that of DHBDLB400 (2′,6′-diCl DHB > 2′-Cl DHB > 6-Cl DHB > 4-Cl DHB > DHB > 5-Cl DHB > 4′-Cl DHB > 3′-Cl DHB [17]). In the presence of saturating concentrations of individual substrates, DHBDP6-I would be inactivated by these compounds in the following order: 6-Cl DHB > 3′-Cl DHB > 5-Cl DHB > 4′-Cl DHB > 4-Cl DHB > DHB > 2′,6′-diCl DHB > 2′-Cl DHB. In contrast, DHBDP6-III would be inactivated by these compounds in the following order: 5-Cl DHB > 4′-Cl DHB > 6-Cl DHB > DHB > 3′-Cl DHB > 4-Cl DHB > 2′,6′-diCl DHB > 2′-Cl DHB. Again, these patterns differ from that of DHBDLB400 (4′-Cl DHB > 3′-Cl DHB > 6-Cl DHB > 4-Cl DHB > 5-Cl DHB > 2′-Cl DHB > DHB > 2′,6′-diCl DHB [17]).

DISCUSSION

R. globerulus strain P6 contains three extradiol ring cleavage enzymes that have been identified as DHBDs. The properties of the highly active preparations of DHBDP6-I and DHBDP6-III described differed slightly from those previously reported for the DHBDP6 isozymes. First, DHBDP6-I and DHBDP6-III in raw extracts of P. putida strain KT2442 displayed strong substrate inhibition for DHB (8). In contrast, these isozymes were subject to minor or no substrate inhibition by DHB in the present study. It is possible that the previous analyses did not adequately account for the rapid inactivation of the enzymes observed at high substrate concentrations. The substrate inhibition observed in DHBDP6-I is similar in magnitude to that observed in DHBDLB400 with most substrates and presumably is due to the binding of a second substrate molecule in the active site of the enzyme, as proposed for DHBDLB400 (43).

A second difference in properties concerns the reactivity of the isozymes with copper. More particularly, a previous report established that 0.1 and 0.2 mM Cu(II) stimulated the DHB cleavage activity of DHBDP6-II by 137 and 165%, respectively (6). In contrast, DHBDP6-I and DHBDP6-III were inhibited by Cu(II) at all of the concentrations tested in the present study. It is unclear whether this difference reflects differences in the enzymes or differences in experimental conditions. In a previous study, DTT was included in the incubation buffer. DTT is highly reactive with transition metals (31), and would likely generate small quantities of Cu(I) and otherwise influence the reactivity of the copper. Interestingly, the specificity of DHBDP6-II for DHB estimated from the reported specific activity and KmAapp (6) is very similar to that of DHBDP6-III reported here. The mechanism of activation of DHBDP6-II by copper remains to be fully elucidated.

It is unclear whether all of the enzymes identified as DHBDs in R. globerulus strain P6 are involved in biphenyl or PCB degradation. Indeed, the apparent specificity of each of the P6 isozymes for DHB is significantly lower than that for DHBDLB400. Thus, the respective apparent specificities of DHBDP6-I and DHBDP6-III for DHB were 1.6 and 21 times lower than that for DHBDLB400 (43). It is unclear whether the low specificities of DHBDP6-II and DHBDP6-III in particular reflect their adaptation to the degradation of other compounds such as PCBs (see below). Interestingly, the apparent Km for oxygen, the KmBapp values, of DHBDP6-I and DHBDP6-III in the presence of DHB are significantly lower than that of DHBDLB400 so the differences in apparent specificity for DHB between the P6 isozymes and DHBDLB400 would not be as great at lower O2 concentrations.

The most striking result of the present study is that DHBDP6-I and DHBDP6-III cleaved certain chlorinated DHBs with higher apparent specificities than DHB. This is in clear contrast to DHBDLB400, whose best substrate is DHB (17). Moreover, the respective specificities of the two P6 isozymes for chlorinated DHBs appear to be quite complementary. Thus, the worst substrate for DHBDP6-III (4′-Cl DHB) was a good substrate for DHBDP6-I and the best substrates for DHBDP6-III (4-Cl DHB and 5-Cl DHB) were the worst substrates for DHBDP6-I. It is likely that the differences in the specificities of the enzymes for polychlorinated DHBs would be even larger. Overall, these data suggest that the existence of multiple DHBD isozymes in a single bacterial strain improves the PCB-degrading capabilities of that strain and suggest that these enzymes may have been recruited or adapted to improve the PCB-degrading capabilities of R. globerulus strain P6.

The different reactivities of DHBDP6-I, DHBDP6-III, and DHBDLB400 towards PCB metabolites is further illustrated by their respective reactivities towards 2′,6′-diCl DHB. All three isozymes turned over this compound very slowly, indicating that the chlorine substituents probably partially occlude the accessibility for O2, as observed in DHBDLB400 (17). However, the KmAapp of the isozymes for 2′,6′-diCl DHB differed by over 500-fold. Moreover, the KmAapp for 2′,6′-diCl DHB was 1,700 times lower than that for DHB in DHBDLB400, 40 times lower than that for DHB in DHBDP6-I, and only 4 times lower than that for DHB in DHBDP6-III. Thus, the P6 isozymes, particularly DHBDP6-III, are not as susceptible to competitive inhibition by 2′,6′-diCl DHB. As this inhibition would prevent the degradation of other chlorinated DHBs, the different KmAapp values of DHBDP6-I and DHBDP6-III for 2′,6′-diCl DHB further demonstrate how the existence of multiple DHBD isozymes in the same strain is advantageous to PCB degradation.

There appears to be no correlation between substrate specificity and susceptibility to inactivation in DHBDP6-I and DHBDP6-III: in general, the best substrates were not those that inactivated the enzymes more slowly. Similarly, both P6 isozymes were relatively resistant to inactivation by DHB although this was not the best substrate of either enzyme. This lack of correlation between specificity and susceptibility to inactivation might reflect the recent evolution of these enzymes for the degradation of PCB metabolites, as PCBs were only recently introduced into the environment in significant amounts. The tuning of the enzyme against inactivation versus optimization of specificity could be more difficult to evolve. Alternatively, R. globerulus strain P6 might possess a XylT-like ferredoxin (28, 34) to reduce oxidized iron in DHBDP6-I and DHBDP6-III. The existence of such a ferredoxin would prevent prolonged inactivation of the enzymes in vivo and might reduce the evolutionary pressure to minimize susceptibility to inactivation. It was recently shown that DHBDLB400 in Burkholderia sp. strain was LB400 inactivated with 3-Cl catechol recovered in vivo in the absence of protein synthesis, indicating the presence of an agent capable of reducing the enzyme in this organism (44).

Commercial mixtures of PCBs typically contain up to 60 different congeners. The effective microbial degradation of these environmental pollutants thus requires enzymes of broad or complementary specificities. The present study of the specificities of DHBDP6-I and DHBDP6-III points to several similarities as well as significant structural or electronic differences in the respective active sites of DHBDP6-I, DHBDP6-III, and DHBDLB400. Structural and spectroscopic studies of DHBDP6-I and DHBDP6-III may provide insights into the molecular basis of these differences. The poor cleavage of 2′,6′-diCl DHB by DHBDP6-I and DHBDP6-III further suggests that directed evolution of DHBD might be worthwhile to improve the cleavage of this recalcitrant metabolite and, ultimately, the microbial degradation of PCBs.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Strategic grants from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC). F.H.V. was the recipient of the Li Tze Fong Memorial and NSERC postgraduate scholarships.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abramowicz, D. A. 1990. Aerobic and anaerobic biodegradation of PCBs: a review. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 10:241-251. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams, R. H., C.-M. Huang, F. K. Higson, V. Brenner, and D. D. Focht. 1992. Construction of a 3-chlorobiphenyl-utilizing recombinant from an intergeneric mating. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:647-654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arciero, D. M., and J. D. Lipscomb. 1986. Binding of 17O-labeled substrate and inhibitors to protocatechuate 4,5-dioxygenase-nitrosyl complex. Evidence for direct substrate binding to the active site Fe2+ of extradiol dioxygenases. J. Biol. Chem. 261:2170-2178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arciero, D. M., A. M. Orville, and J. D. Lipscomb. 1985. [17O]Water and nitric oxide binding by protocatechuate 4,5-dioxygenase and catechol 2,3-dioxygenase. Evidence for binding of exogenous ligands to the active site Fe2+ of extradiol dioxygenases. J. Biol. Chem. 260:14035-14044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arensdorf, J. J., and D. D. Focht. 1994. Formation of chlorocatechol meta cleavage products by a pseudomonad during metabolism of monochlorobiphenyls. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:2884-2889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asturias, J. A., L. D. Eltis, M. Prucha, and K. N. Timmis. 1994. Analysis of three 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl 1,2-dioxygenases found in Rhodococcus globerulus P6. J. Biol. Chem. 269:7807-7815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asturias, J. A., E. Moore, M. M. Yakimov, S. Klatte, and K. N. Timmis. 1994. Reclassification of the polychlorinated biphenyl-degraders Acinetobacter sp. P6 and Corynebacterium sp. strain MB1 as Rhodococcus globerulus. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 17:226-231. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asturias, J. A., and K. N. Timmis. 1993. Three different 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl-1,2-dioxygenase genes in the gram-positive polychlorobiphenyl-degrading bacterium Rhodococcus globerulus P6. J. Bacteriol. 175:4631-4640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl. 2000. Current protocols in molecular biology. J. Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 10.Barriault, D., M. M. Plante, and M. Sylvestre. 2002. Family shuffling of a targeted bphA region to engineer biphenyl dioxygenase. J. Bacteriol. 184:3794-3800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bedard, D. L., and M. L. Haberl. 1990. Influence of chlorine substitution pattern on the degradation of polychlorinated biphenyls by eight bacterial strains. Microb. Ecol. 20:87-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bedard, D. L., R. Unterman, L. H. Bopp, M. J. Brennan, M. L. Haberl, and C. Johnson. 1986. Rapid assay for screening and characterizing microorganisms for the ability to degrade polychlorinated biphenyls. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 51:761-768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bopp, L. H. 1986. Degradation of highly chlorinated PCBs by Pseudomonas strain LB400. J. Ind. Microbiol. 1:23-29. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruhlmann, F., and W. Chen. 1999. Transformation of polychlorinated biphenyls by a novel BphA variant through the meta-cleavage pathway. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 179:203-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cornish-Bowden, A. 1995. Analysis of enzyme kinetic data. Oxford University Press, New York, N.Y.

- 17.Dai, S., F. H. Vaillancourt, H. Maaroufi, N. M. Drouin, D. B. Neau, V. Snieckus, J. T. Bolin, and L. D. Eltis. 2002. Identification and analysis of a bottleneck in PCB biodegradation. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9:934-939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Lorenzo, V., L. D. Eltis, B. Kessler, and K. N. Timmis. 1993. Analysis of Pseudomonas gene products using lacIq/Ptrp-lac plasmids and transposons that confer conditional phenotypes. Gene 123:17-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eltis, L. D., and J. T. Bolin. 1996. Evolutionary relationships among extradiol dioxygenases. J. Bacteriol. 178:5930-5937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eltis, L. D., S. G. Iwagami, and M. Smith. 1994. Hyperexpression of a synthetic gene encoding a high potential iron sulfur protein. Protein Eng. 7:1145-1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Furukawa, K. 2000. Biochemical and genetic bases of microbial degradation of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs). J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 46:283-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Furukawa, K., F. Matsumura, and K. Tonomura. 1978. Alcaligenes and Acinetobacter capable of degrading polychlorinated biphenyls. Agric. Biol. Chem. 42:543-548. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Furukawa, K., N. Tomizuka, and A. Kamibayashi. 1979. Effect of chlorine substitution on the bacterial metabolism of various polychlorinated biphenyls. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 38:301-310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haigler, B. E., and D. T. Gibson. 1990. Purification and properties of NADH-ferredoxinNAP reductase, a component of naphthalene dioxygenase from Pseudomonas sp. strain NCIB 9816. J. Bacteriol. 172:457-464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han, S., L. D. Eltis, K. N. Timmis, S. W. Muchmore, and J. T. Bolin. 1995. Crystal structure of the biphenyl-cleaving extradiol dioxygenase from a PCB-degrading pseudomonad. Science 270:976-980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herrero M., V. de Lorenzo, and K. N. Timmis. 1990. Transposon vectors containing non-antibiotic resistance selection markers for cloning and stable chromosomal insertion of foreign genes in gram-negative bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 172:6557-6567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hori, K., T. Hashimoto, and M. Nozaki. 1973. Kinetic studies on the reaction mechanism of dioxygenases. J. Biochem. 74:375-384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hugo, N., C. Meyer, J. Armengaud, J. Gaillard, K. N. Timmis, and Y. Jouanneau. 2000. Characterization of three XylT-like [2Fe-2S] ferredoxins associated with catabolism of cresols or naphthalene: evidence for their involvement in catechol dioxygenase reactivation. J. Bacteriol. 182:5580-5585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kohler, H.-P. E., D. Kholer-Staub, and D. D. Focht. 1988. Cometabolism of polychlorinated biphenyls: enhanced transformation of Aroclor 1254 by growing bacterial cells. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 54:1940-1945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kosono, S., M. Maeda, F. Fuji, H. Arai, and T. Kudo. 1997. Three of the seven bphC genes of Rhodococcus erythropolis TA421, isolated from a termite ecosystem, are located on an indigenous plasmid associated with biphenyl degradation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3282-3285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krezel, A., W. Lesniak, M. Jezowska-Bojczuk, P. Mlynarz, J. Brasun, H. Kozlowski, and W. Bal. 2001. Coordination of heavy metals by dithiothreitol, a commonly used thiol group protectant. J. Inorg. Biochem. 84:77-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kulakov, L. A., V. A. Delcroix, M. J. Larkin, V. N. Ksenzenko, and A. N. Kulakova. 1998. Cloning of new Rhodococcus extradiol dioxygenase genes and study of their distribution in different Rhodococcus strains. Microbiology 144:955-963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nerdinger, S., C. Kendall, R. Marchhart, P. Riebel, M. R. Johnson, C.-F. Yin, L. D. Eltis, and V. Snieckus. 1999. Directed ortho-metalation and Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling connections: regiospecific synthesis of all isomeric chlorodihydroxybiphenyls for microbial degradation studies of PCBs. Chem. Commun. 1999:2259-2260. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Polissi, A., and S. Harayama. 1993. In vivo reactivation of catechol 2,3-dioxygenase mediated by a chloroplast-type ferredoxin: a bacterial strategy to expand the substrate specificity of aromatic degradative pathways. EMBO J. 12:3339-3347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmid, A., B. Rothe, J. Altenbuchner, W. Ludwig, and K.-H. Engesser. 1997. Characterization of three distinct extradiol dioxygenases involved in mineralization of dibenzofuran by Terrabacter sp. strain DPO360. J. Bacteriol. 179:53-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seah, S. Y. K., G. Labbé, S. R. Kaschabek, F. Reifenrath, W. Reineke, and L. D. Eltis. 2001. Comparative specificities of two evolutionarily divergent hydrolases involved in microbial degradation of polychlorinated biphenyls. J. Bacteriol. 183:1511-1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seah, S. Y. K., G. Labbé, S. Nerdinger, M. R. Johnson, V. Snieckus, and L. D. Eltis. 2000. Identification of a serine hydrolase as a key determinant in the microbial degradation of polychlorinated biphenyls. J. Biol. Chem. 275:15701-15708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seeger, M., K. N. Timmis, and B. Hofer. 1995. Conversion of chlorobiphenyls into phenylhexadienoates and benzoates by the enzymes of the upper pathway for polychlorobiphenyl degradation encoded by the bph locus of Pseudomonas sp. strain LB400. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:2654-2658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seeger, M., K. N. Timmis, and B. Hofer. 1995. Degradation of chlorobiphenyls catalyzed by the bph-encoded biphenyl-2,3-dioxygenase and biphenyl-2,3-dihydrodiol-2,3-dehydrogenase of Pseudomonas sp. LB400. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 133:259-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shimizu, S., H. Kobayashi, E. Masai, and M. Fukuda. 2001. Characterization of the 450-kb linear plasmid in a polychlorinated biphenyl degrader, Rhodococcus sp. strain RHA1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:2021-2028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sondossi, M., M. Sylvestre, and D. Ahmad. 1992. Effects of chlorobenzoate transformation on the Pseudomonas testosteroni biphenyl and chlorobiphenyl degradation pathway. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:485-495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suenaga, H., T. Watanabe, M. Sato, Ngadiman, and K. Furukawa. 2002. Alteration of regiospecificity in biphenyl dioxygenase by active-site engineering. J. Bacteriol. 184:3682-3688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vaillancourt, F. H., S. Han, P. D. Fortin, J. T. Bolin, and L. D. Eltis. 1998. Molecular basis for the stabilization and inhibition of 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl 1,2-dioxygenase by t-butanol. J. Biol. Chem. 273:34887-34895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vaillancourt, F. H., G. Labbé, N. M. Drouin, P. D. Fortin, and L. D. Eltis. 2002. The mechanism-based inactivation of 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl 1,2-dioxygenase by catecholic substrates. J. Biol. Chem. 277:2019-2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]