Abstract

1 Abdominal skin of 25 human subjects was irradiated with three times its minimal erythema dose of ultraviolet (u.v.) B radiation. Erythema appeared after 2 h, was of moderate degree at 6 h, and maximal at 24 and 48 h.

2 Exudate was recovered by a suction bulla technique from the subject's normal and erythematous skin either at 6, 24 or 48 h after irradiation.

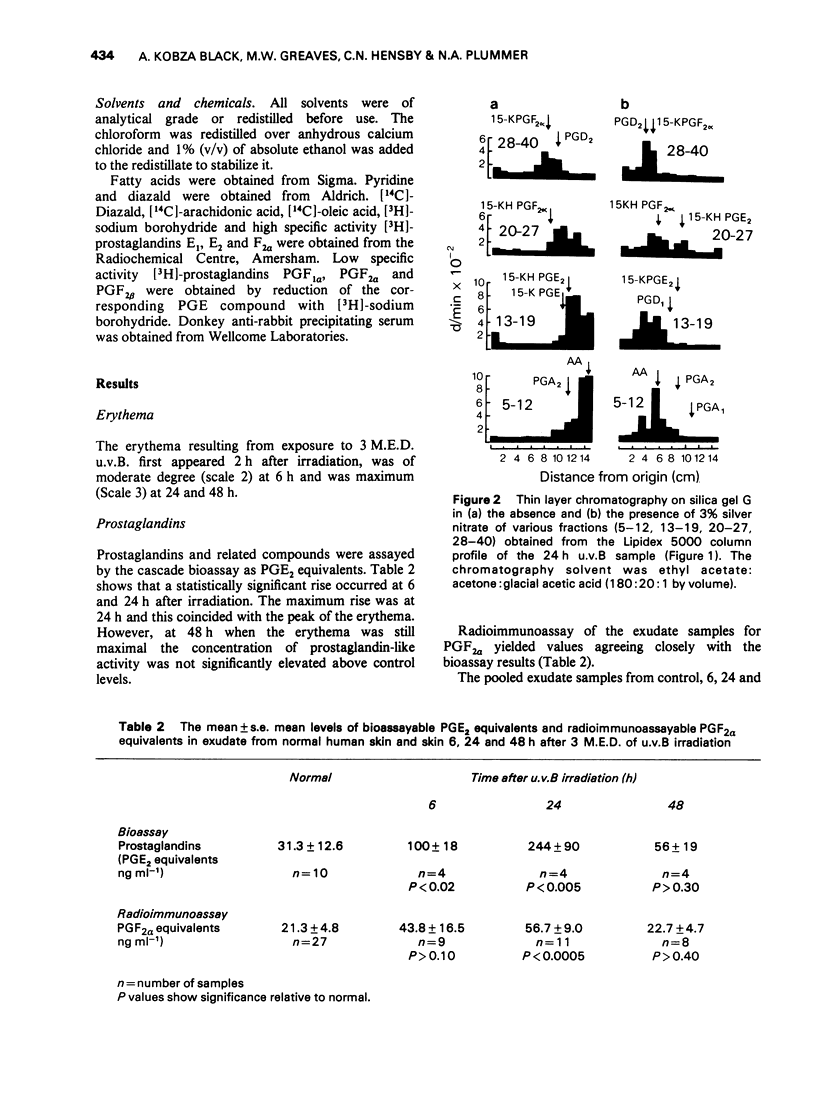

3 Superfusion cascade bioassay of exudate showed increased prostaglandin (PG)-like activity, measured in PGE2 equivalents, at 6 and 24 h after irradiation. The maximum rise was at 24 h, coinciding with the peak of the erythema. However, prostaglandin concentrations were not significantly above that of controls at 48 h when the erythema was still maximal.

4 Radioimmunoassay for PGF2α yielded values in close agreement with the bioassay results.

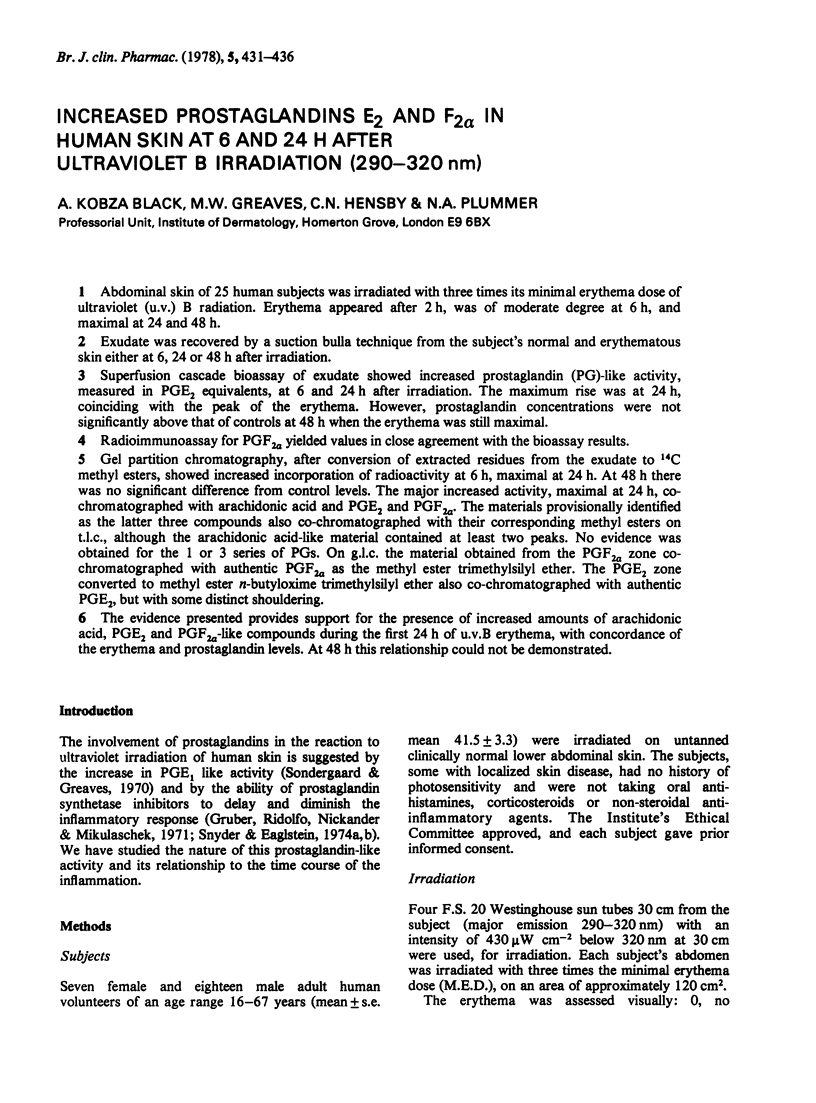

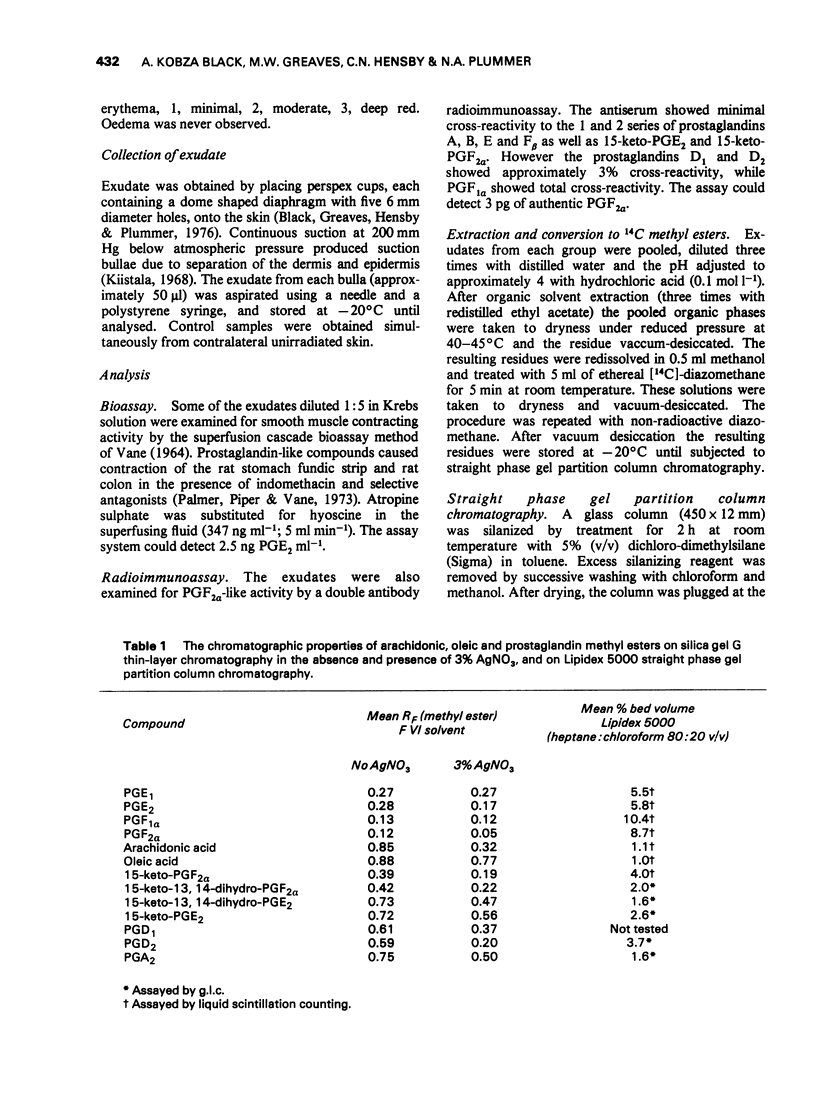

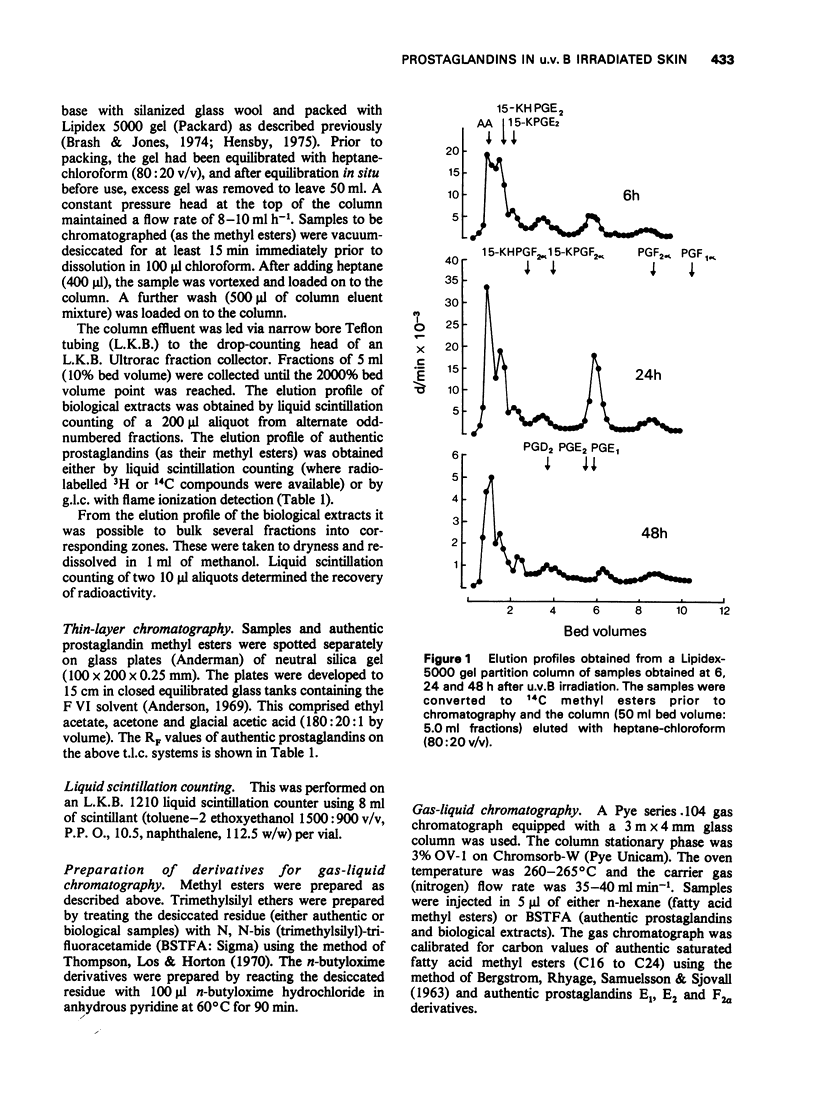

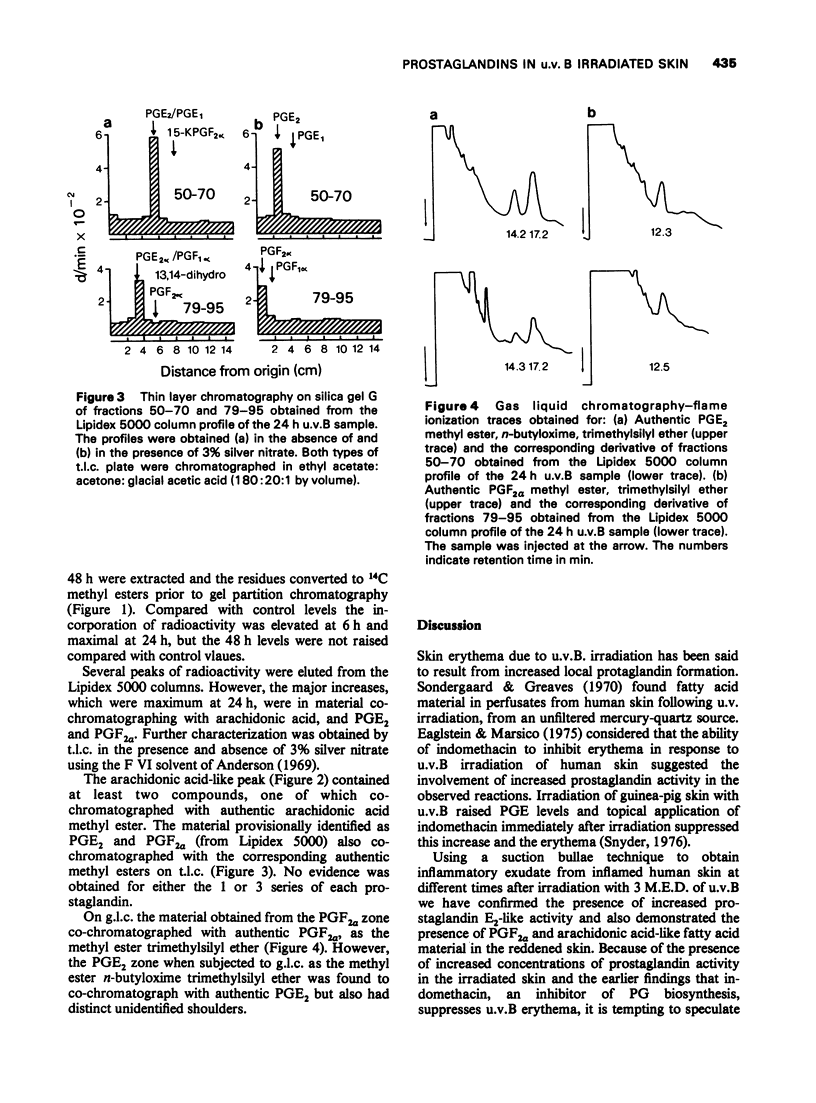

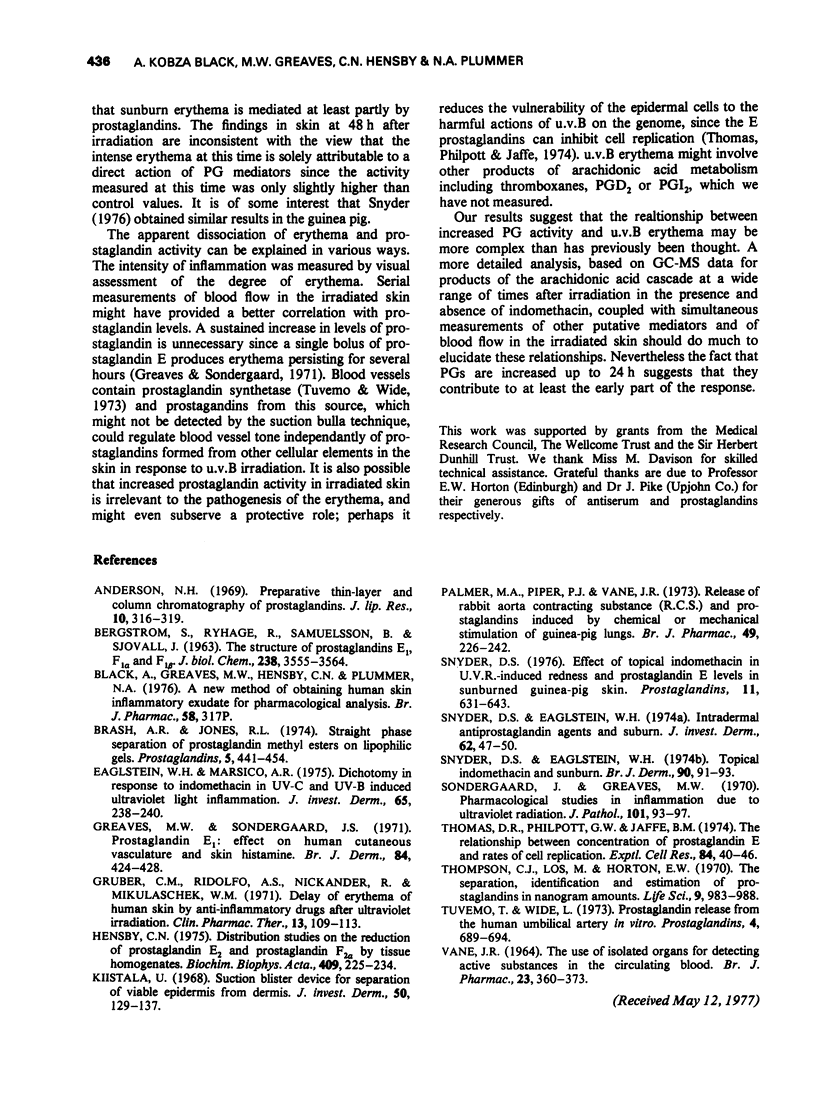

5 Gel partition chromatography, after conversion of extracted residues from the exudate to 14C methyl esters, showed increased incorporation of radioactivity at 6 h, maximal at 24 h. At 48 h there was no significant difference from control levels. The major increased activity, maximal at 24 h, co-chromatographed with arachidonic acid and PGE2 and PGF2α. The materials provisionally identified as the latter three compounds also co-chromatographed with their corresponding methyl esters on t.l.c., although the arachidonic acid-like material contained at least two peaks. No evidence was obtained for the 1 or 3 series of PGs. On g.l.c. the material obtained from the PGF2α zone co-chromatographed with authentic PGF2α as the methyl ester trimethylsilyl ether. The PGE2 zone converted to methyl ester n-butyloxime trimethylsilyl ether also co-chromatographed with authentic PGE2, but with some distinct shouldering.

6 The evidence presented provides support for the presence of increased amounts of arachidonic acid, PGE2 and PGF2α-like compounds during the first 24 h of u.v.B erythema, with concordance of the erythema and prostaglandin levels. At 48 h this relationship could not be demonstrated.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- BERGSTROEM S., RYHAGE R., SAMUELSSON B., SJOEVALL J. PROSTAGLANDINS AND RELATED FACTORS. 15. THE STRUCTURES OF PROSTAGLANDIN E1, F1-ALPHA, AND F1-BETA. J Biol Chem. 1963 Nov;238:3555–3564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brash A. R., Jones R. L. Straight phase separation of prostaglandin methyl esters on lipophilic gels. Prostaglandins. 1974 Mar 10;5(5):441–454. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(74)80014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaglstein W. H., Marsico A. R. Dichotomy in response to indomethacin in UV-C and UV-B induced ultraviolet light inflammation. J Invest Dermatol. 1975 Aug;65(2):238–240. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12598255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber C. M., Jr, Ridolfo A. S., Nickander R., Mikulaschek W. M. Delay of erythema of human skin by anti-inflammatory drugs after ultraviolet irradiation. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1972 Jan-Feb;13(1):109–113. doi: 10.1002/cpt1972131109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensby C. N. Distribution studies on the reduction of prostaglandin E2 to prostaglandin F2alpha by tissue homogenates. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1975 Nov 21;409(2):225–234. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(75)90157-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiistala U. Suction blister device for separation of viable epidermis from dermis. J Invest Dermatol. 1968 Feb;50(2):129–137. doi: 10.1038/jid.1968.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer M. A., Piper P. J., Vane J. R. Release of rabbit aorta contracting substance (RCS) and prostaglandins induced by chemical or mechanical stimulation of guinea-pig lungs. Br J Pharmacol. 1973 Oct;49(2):226–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1973.tb08368.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder D. S., Eaglstein W. H. Topical indomethacin and sunburn. Br J Dermatol. 1974 Jan;90(1):91–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder D. S. Effect of topical indomethacin on UVR-induced redness and prostaglandin E levels in sunburned guinea pig skin. Prostaglandins. 1976 Apr;11(4):631–643. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(76)90066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sondergaard J., Greaves M. W. Pharmacological studies in inflammation due to exposure to ultraviolet radiation. J Pathol. 1970 Jun;101(2):93–97. doi: 10.1002/path.1711010204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sondergaard J., Greaves M. W. Prostaglandin E1: effect on human cutaneous vasculature and skin histamine. Br J Dermatol. 1971 May;84(5):424–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1971.tb02527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas D. R., Philpott G. W., Jaffe B. M. The relationship between concentration of prostaglandin E and rates of cell replication. Exp Cell Res. 1974 Mar 15;84(1):40–46. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(74)90377-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson C. J., Los M., Horton E. W. The separation, identification and estimation of prostaglandins in nanogram quantities by combined gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Life Sci I. 1970 Sep 1;9(17):983–988. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(70)90121-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuvemo T., Wide L. Prostaglandin release from the human umbilical artery in vitro. Prostaglandins. 1973 Nov;4(5):689–694. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(73)80051-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VANE J. R. THE USE OF ISOLATED ORGANS FOR DETECTING ACTIVE SUBSTANCES IN THE CIRCULATING BLOOD. Br J Pharmacol Chemother. 1964 Oct;23:360–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1964.tb01592.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]