Abstract

Due to the abnormal vasculature of solid tumors, tumor cell oxygenation can change rapidly with the opening and closing of blood vessels, leading to the activation of both hypoxic response pathways and oxidative stress pathways upon reoxygenation. Here, we report that ataxia telangiectasia mutated-dependent phosphorylation and activation of Chk2 occur in the absence of DNA damage during hypoxia and are maintained during reoxygenation in response to DNA damage. Our studies involving oxidative damage show that Chk2 is required for G2 arrest. Following exposure to both hypoxia and reoxygenation, Chk2−/− cells exhibit an attenuated G2 arrest, increased apoptosis, reduced clonogenic survival, and deficient phosphorylation of downstream targets. These studies indicate that the combination of hypoxia and reoxygenation results in a G2 checkpoint response that is dependent on the tumor suppressor Chk2 and that this checkpoint response is essential for tumor cell adaptation to changes that result from the cycling nature of hypoxia and reoxygenation found in solid tumors.

Accurate DNA replication and division are essential for the survival of all living organisms. To safeguard the integrity of the genome, cells contain conserved pathways that monitor and respond to DNA damage, ensuring that proper DNA replication, cell division, and growth occur. Some causes of DNA damage include ionizing radiation (IR), UV radiation (UV), and chemotherapeutic agents. The resulting double-stranded breaks, single-stranded breaks, and stalled replication forks lead to the activation of checkpoint responses and subsequent cell cycle arrest in the G1 and S phases of the cell cycle or to apoptosis. In contrast, the physiological stress of hypoxia does not induce DNA damage but does lead to rapid replication arrest due to stalled replication forks (23). However, hypoxia followed by reoxygenation in cells has been shown to cause significant levels of DNA damage (24).

Two of the proteins responsible for initiating the DNA damage response in mammals are ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) and ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3 related (ATR). Both are members of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase-related protein kinase family and have functional domains that possess serine/threonine kinase activity. The ATM kinase responds very rapidly to low levels of DNA damage, leading to a conformational change which stimulates autophosphorylation. The result is a dissociation of the inactive homodimer into active monomers that can phosphorylate a variety of effector proteins involved in cell cycle control and DNA repair (4). In contrast, ATR responds primarily to damage that causes bulky DNA adducts and stalled replication forks, such as alkylating agents, UV radiation, and hypoxia (15). ATR also responds to ionizing radiation but with delayed kinetics compared to ATM, possibly as a result of S-phase arrest (1, 28). Of the many downstream targets of ATM and ATR, the tumor suppressors Chk1 and Chk2 have been suggested to play important roles in regulating the G2 checkpoint response to DNA damage (3, 28, 42, 45, 47, 67). Chk1 is an essential gene, and without it, embryonic lethality occurs early in development (42). Discovery of cancer-associated Chk1 mutations has been limited to colon, stomach, and endometrial carcinomas and is extremely rare (9, 49, 65). On the other hand, complete deficiency of Chk2 in mice is nonlethal and has been hypothesized not to play a significant role in tumorigenesis (61). However, new data in humans indicate otherwise. Chk2 mutations occur in a number of sporadic cancers, including lung cancer (46), and in a subset of cases of Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Epigenetic changes in Chk2 have also been identified in both bladder and breast cancers (6, 58). As new data emerge, our understanding of the mechanism by which Chk2 contributes to genetic instability makes it clear that further study of this protein is warranted.

Chk2 is a serine/threonine protein kinase capable of phosphorylating a number of proteins involved in the DNA damage response. When activated by phosphorylation on threonine 68, it displays kinase activity towards a variety of targets, which include Cdc25A, Cdc25C, Brca1, and p53. All of these proteins can contribute to cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, and/or repair (5, 29, 30, 40, 61, 72). Chk2 has been linked to G2 arrest through its ability to interact with Cdc25C (45). In response to ionizing radiation, Chk2 phosphorylates Cdc25C at the serine 216 residue, creating a binding site for 14-3-3 proteins, which then sequester Cdc25C in the cytoplasm, effectively disrupting its protein phosphatase activity (52). Without functional Cdc25C, Cdc2 remains phosphorylated and unable to form an active complex with cyclin B, resulting in cell cycle arrest in G2 phase (50).

Investigation of the role Chk2 plays in response to damage has led to conflicting results. Studies utilizing mouse models indicated that Chk2 deficiency resulted in loss of checkpoint function, radioresistant DNA synthesis, and defective p53-mediated transcription (30, 61). On the other hand, targeted gene disruption of Chk2 in the diploid human colon carcinoma cell line HCT116 showed that the response to ionizing radiation was intact, regardless of Chk2 status (36). Cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, p53 phosphorylation at Ser 20, p53 accumulation, and transcriptional activation were all unaltered in cells lacking Chk2 in the human colon cancer cells examined. A third study utilizing antisense inhibition of Chk2, also in human cells, reported increased p53-independent apoptosis (70). In addition, DNA-methylating agents, such as N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (MNNG), are known to induce mismatch repair-dependent G2 arrest that is dependent on Chk1 and Chk2 (2). Interestingly, Chk1 has also been described as having an essential role in DNA damage-induced G2 arrest, but this appears to be dependent on the system and type of DNA damage (42, 67). Less well characterized than the response to IR-, UV-, or chemically induced DNA damage is the physiological stress response that cells are subjected to within the tumor microenvironment, where fluctuating oxygen tensions elicit a damage response. Here, loss of a checkpoint function has a potentially significant impact with regard to both tumor progression and therapy.

Oxidative stress can be found in numerous disease settings. During ischemic injury to the brain, heart, lungs, kidney, or other organs, reoxygenation is known to induce the formation of reactive oxygen species, resulting in much of the tissue damage that is characteristic of these pathologies (14, 41, 53, 59, 69, 74). In other diseases, such as cancer, the tumor microenvironment contains hypoxic regions resulting from the formation of defective vasculature (56, 57). Studies show that due to limited oxygen diffusion distance, nearly all solid tumors have regions of chronic and acute hypoxia (11, 63). As a result of tumor hypoxia, there is a decrease in efficacy of chemotherapy and radiotherapy, both of which require adequate perfusion for maximal results (11, 64, 71). Therefore, increased hypoxia is also associated with a poor prognosis and a more aggressive phenotype (31-33).

Cells subjected to hypoxia (<0.01% O2) arrest in G1 and S phases of the cell cycle (21, 22, 25, 54). In response to hypoxia, it was reported by Gibson et al. that Chk2 is phosphorylated in an ATM-dependent manner. Although hypoxia itself is not associated with increased DNA damage in the form of DNA strand breaks (single-stranded breaks or double-stranded breaks), acute hypoxia often does not exist alone, and in the tumor, it is inevitably followed by reoxygenation, which does induce DNA damage (26). Recently, reoxygenation was identified as a novel mechanism for activating ATM in response to DNA damage (25). Since Chk2, a prime effector of ATM in response to DNA damage, plays an essential role in regulating the DNA damage response, we hypothesized that Chk2 mediates the damage response induced by reoxygenation through ATM-dependent phosphorylation. Here, we report that Chk2 is required for reoxygenation-induced G2 arrest and that loss of Chk2 results in increased apoptosis and decreased survival. Therefore, Chk2 is an essential gene in the mammalian response to the cycling stress of hypoxia and reoxygenation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines.

The HCT116 Chk2+/+, Chk2−/−, and p53−/− human colorectal carcinoma cell lines were cultured in McCoy's 5A medium with 90% 1.5 mM l-glutamine and 10% fetal bovine serum (36). RKO colorectal carcinoma cell line was cultured in 90% Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium and 10% fetal bovine serum. YZ3 (ATM+/+) and pEBS (ATM−/−) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 10% fetal bovine serum and supplemented with 100 μg/ml hygromycin (73). Lymphoblastoid cell lines GM0536 (ATM−/−), isolated from an ataxia telangiectasia patient, and GM1526 (ATM+/+, p53+/+), which was Epstein-Barr virus immortalized, were cultured in RPMI medium supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum (12).

Hypoxia induction and reoxygenation.

All cells were cultured on glass dishes for hypoxia unless otherwise noted. Hypoxia treatment described in this work refers to conditions of less than 0.01% O2 and was carried out using a hypoxic chamber (Sheldon Corp., Cornelius, Oreg.). For reoxygenation, glass dishes were removed from the chamber and placed in a tissue culture incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2.

RNA interference.

Cells were plated in six-well plastic dishes at 60% density for small interfering RNA (siRNA) transfection with Oligofectamine (Invitrogen). Either 200 nM of “SMARTpool” Chk2 siRNA or control nontargeting siRNA (Dharmacon, Lafayette, Co.) and Oligofectamine was diluted in serum and antibiotic-free OptiMEM (Invitrogen) and incubated for 10 min as per the manufacturer's protocol. On the following day, cells were split into glass plates for hypoxia/reoxygenation experiments.

Retroviral transduction/infection.

A previously published protocol for retroviral transfection/infection used in these studies can be found on the laboratory website of Gary Nolan (Stanford University; http://www.stanford.edu/group/nolan/protocols/pro_helper_dep.html).

Following infection, stable integrants were selected with puromycin.

Apoptosis quantitation.

Morphological changes indicative of apoptosis were highlighted by staining cells with the two nuclear dyes: Hoescht 3342 (20 μg/ml; Sigma) for visualization of changes in nuclear characteristics and propidium iodide (PI) (15 μg/ml; Sigma) to visualize the loss of membrane integrity. Cells were plated subconfluently prior to hypoxia/reoxygenation treatment. Three fields of more than 200 cells/field were counted.

Survival and growth competition assays.

Cells were counted and plated in triplicate on glass dishes, allowed to attach for 6 h, and then exposed to hypoxia (0.01% oxygen) or gamma irradiation. Cells were cultured undisturbed for 10 to 14 days at 37°C and 5% CO2. Colonies were stained with crystal violet, plating efficiency was determined, and results were plotted as the fractions of the colonies counted under aerobic conditions. For reoxygenation growth competition, two-well tissue chamber slides were coated with 5 μg/cm2 poly-l-lysine for 1 h and then rinsed. HCT116 Chk2+/+ and Chk2−/− cells stably expressing enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP) and enhanced cyan fluorescent protein (ECFP) were counted and mixed in a 1:1 ratio and then plated onto the coated chamber slides. Cells were allowed to adhere for 6 h before being placed in the hypoxia chamber for 15 h. Upon removal from the chamber, cells were reoxygenated for 1, 2, or 3 days. Upper chambers were removed, and slides were mounted with VECTASHIELD (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, Calif.) and sealed. Fluorescent cells were visualized and counted using a Nikon Axiophot microscope. Three fields of more than 300 cells were counted for each time point.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis.

Cells were collected following hypoxia/reoxygenation treatment, rinsed, and suspended in 1 ml phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) before ethanol fixation. For G2 checkpoint assay, cells were rinsed once with PBS and permeabilized and stained with 10 μg/ml anti-phospho-histone H3 (pH3; Upstate, product number 06-570) for 2.5 to 3 h. Goat anti-rabbit fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch) diluted 1:30 in 1% bovine serum albumin/PBS secondary was used to label the pH3-positive cells. Cells were analyzed using CellQuest software on a FACSCalibur system (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). For S-phase arrest assay, 20 μM BrdU [(+)-5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine; Sigma Chemical Company] was added to the medium for 1 h prior to harvesting. Cells were fixed and incubated for 30 min in 10 μl/ml of anti-BrdU FITC antibody (catalog no. 347583; BD-Biosciences, San Jose, CA). After one rinse in PBS-0.5% Tween-1% bovine serum albumin, cells were incubated on ice for 1 hour in PBS with 5 μg/ml propidium iodide and 0.1 mg/ml RNase A (R-5503; Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Company).

Immunoblotting.

Protein extracts were harvested with lysis buffer (10% Triton X-100, 10% sodium dodecyl suflate, 1.0 M Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], and 5 M NaCl) supplemented with 50× protease inhibitor (PharMingnen BD) and a phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (2 mM sodium orthovanadate, 2 mM EGTA, 12 mM B-glycerol phosphate, 10 mM sodium fluoride, and 16 μg/ml benzamidine hydrochloride). To detect total ATM (1:800) (GeneTex) and phospho-Ser 1981 ATM (1:700) (Rockland), extracts were separated on a 6% acrylamide gel, transferred to a polyvinylidine difluoride membrane, and probed overnight at 4°C. Membranes were incubated for 30 min in secondary horseradish peroxidase mouse and rabbit antibodies (1:5,000) (Amersham Biosciences). Proteins were detected by chemiluminescence with ECL Plus. Total Chk2 (1:1,000) (Upstate Biotechnology), phospho-Thr 68 Chk2 (1:800) (Cell Signaling), Cdc25A (1:500) (Santa Cruz), total Cdc25C (1:1,000) (Santa Cruz), phospho-S216 Cdc25C (1:100) (Santa Cruz), α-tubulin (1:5,000) (Research Diagnostics Inc.), and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; 1:5,000) (Research Diagnostics Inc.) were all detected following separation on an 8% acrylamide gel. Phospho Tyr15 Cdc2 (1:1,000) (Cell Signaling) was detected after separation on a 10% gel.

Comet assay and ROS scavenging.

A comet assay was performed as previously described (51). Briefly, cells were plated 1 day before treatment at a concentration of 2 × 104 on 60-mm glass dishes. HCT116 wild-type (wt) and Chk2−/− cells were subjected to 15 h of hypoxia. For the hypoxic samples, cells were trypsinized, resuspended in agarose, spread evenly onto precleaned microscope slides, and lysed inside the chamber with equilibrated lysis buffer. Samples for reoxygenation time points were removed from the hypoxia chamber and processed as indicated. For uniformity, all samples were electrophoresed on the same gel. For each sample, a median tail moment was derived from the scoring of 200 cells. For reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging experiments, cells were treated with 10 mM N-acetyl-l-cysteine (NAC) (pH 7.0) for 1 hour before exposure to hypoxia and reoxygenation. Cells were fixed and stained with propidium iodide for cell cycle analysis by FACS.

RESULTS

G2 arrest in cells exposed to hypoxia and reoxygenation.

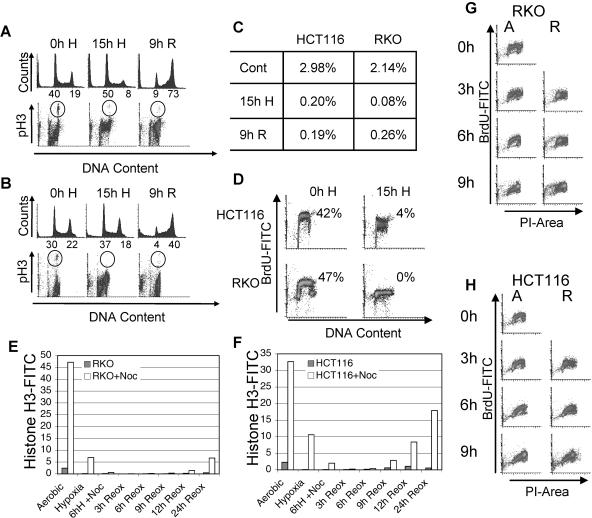

We investigated the cell cycle response to hypoxia and reoxygenation, which frequently occurs in solid tumors, and found that this combination of stresses caused cells to undergo a DNA damage response. After exposure to hypoxia (0.01% oxygen) and reoxygenation, cell cycle distribution, mitotic fraction, and S-phase arrest were determined by FACS analysis of labeled cells. Results are shown for the colon carcinoma cell lines HCT116 and RKO (Fig. 1). As in previous reports, we found that cells exposed to hypoxia arrested in both G1 and S phases of the cell cycle (Fig. 1A, B, and D) (21, 38). Dot blot profiles of the BrdU-labeled S-phase populations visible in untreated cells are absent under hypoxic conditions, demonstrating that cells have undergone replication arrest (Fig. 1D). Comparison of the histogram profiles of DNA content indicates that G1 cells also are arrested and do not enter S phase. After exposure to 15 h of hypoxia, neither HCT116 nor RKO cells entered mitosis (Fig. 1A to C). In untreated HCT116 and RKO cells, respectively, 2.98% and 2.14% of cells were mitotic while cells exposed to 15 h of hypoxia had a deficiency of mitotic cells, with only 0.18% and 0.07% of cells undergoing mitosis. This suggests that in addition to G1- and S-phase arrests, hypoxic cells also undergo a G2-phase arrest. In order to rule out the possibility that cells are cycling more slowly under hypoxia and are not actually arrested in G2, we exposed cells to hypoxia with nocodazole to arrest them in mitosis and then assessed pH3 staining. We found that 5.8 and 10.5% of cells treated with nocodazole for the duration of hypoxia were positive for pH3, a marker of mitosis, in RKO and HCT116 cells, respectively, while only 0.55 and 2.04% of cells treated with 5 h of hypoxia before the addition of nocodazole were positive for pH3 in RKO and HCT116 cells, respectively (Fig. 1E and F). We concluded that during the initial hours of hypoxia, some cells still divide but that during extended periods of hypoxia, cells come to a complete arrest in all phases of the cell cycle.

FIG. 1.

Reoxygenation-induced arrest in HCT116 and RKO cell lines. Colon carcinoma cells arrest in the G2 phase of the cell cycle following exposure to hypoxia and reoxygenation. FACS analysis of PI-stained DNA and FITC-labeled pH3 in HCT116 (A) or RKO (B) cells either untreated (0h H), exposed to 15 h of hypoxia (15h H), or exposed to 15 h hypoxia and 9 h of reoxygenation (9h R). The percentages of cells in G1 and G2 are indicated below the axes of the histograms. (C) Quantification of FITC-pH3 staining in panels A and B. (D) HCT116 and RKO cells undergo replication arrest during exposure to hypoxia. FACS analysis of BrdU incorporation in untreated cells (0h H) and those exposed to 15 h of hypoxia (H). RKO (E) and HCT116 (F) cells were subjected to hypoxia and reoxygenation (Reox). Cells were arrested in G2 by the addition of nocodazole during hypoxia or during reoxygenation and then analyzed by FACS for FITC-labeled phospho-histone H3 and DNA stained with propidium iodide. For hypoxic samples, nocodazole (Noc) was added immediately or after 6 h of hypoxia (6h H), while for reoxygenation samples, nocodazole was added immediately upon removal from hypoxia. Both RKO (G) and HCT116 (H) were exposed to 15 h of hypoxia and up to 9 h of reoxygenation. S-phase cells were labeled with BrdU for 1 hour between 2 and 3 hours of reoxygenation. For a control (0), untreated cells were also labeled with BrdU for 1 hour. FACS analysis of FITC-BrdU- and propidium iodide-labeled cells is shown. Hours of either aerobic conditions (A) or reoxygenation (R) are shown along the FITC-BrdU axes.

To analyze the cell cycle response to reoxygenation, we removed the cells from hypoxia and harvested them after various periods of incubation under normal culture conditions. During reoxygenation, HCT116 and RKO cells arrested in G2 remained there with only 0.19% and 0.26% of cells, respectively, undergoing mitosis after 9 h of reoxygenation (Fig. 1A to C). Histograms of DNA content show that nearly all cells accumulate in the G2 phase of the cell cycle during reoxygenation (Fig. 1A and B). To determine whether cells were cycling more slowly during reoxygenation, we treated cells with nocodazole upon their removal from hypoxia and assessed pH3 staining over the course of 24 h (Fig. 1E and F). We found that through 9 h of reoxygenation, 0.29% of nocodazole-treated RKO cells had reached mitosis compared to 0.04% of cells without nocodazole. In cells not exposed to hypoxia, 47% were arrested in mitosis after 9 h of nocodazole. Similar results were obtained for HCT116 cells. To determine if cells progress more slowly through S phase during reoxygenation, we BrdU pulse-labeled and nocodazole treated cells after removal from hypoxia and compared expression of BrdU-labeled cells through the cell cycle during reoxygenation to normally cycling cells (Fig. 1G and H). Cell cycle progression did not appear significantly different in reoxygenated cells. The combination of mitotic inhibition and G2 accumulation indicates that exposure to hypoxia or to hypoxia and reoxygenation induces a variety of checkpoint responses in these cells, resulting in activation of the G1, S, and G2 checkpoints.

Loss of Chk2 results in attenuated G2 arrest and decreased viability following hypoxia and reoxygenation.

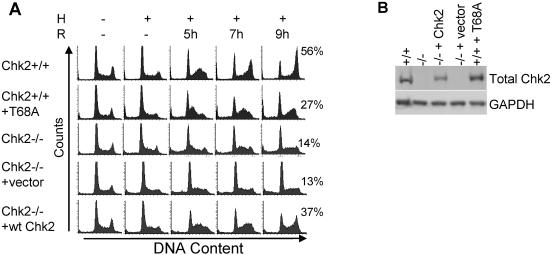

Based on recent findings describing ATM activation in response to reoxygenation as well as induction of DNA damage during early reoxygenation time points but not during hypoxia, we hypothesized that the G2 arrest observed during reoxygenation could be the result of DNA damage activating ATM and its downstream targets (24, 25). Several protein kinases have been reported to regulate G2 arrest, including Chk1 and Chk2. However, since ATM has been shown to be active and likely induced by the DNA damage detected during reoxygenation, Chk2 appeared to be a good candidate for mediating this effect. To test this hypothesis, we first used genetically matched HCT116 cells that differ at their Chk2 loci (36). HCT116 Chk2+/+ and HCT116 Chk2−/− cells were exposed to hypoxia and reoxygenation (Fig. 2A). During reoxygenation, some Chk2+/+ cells that arrested during hypoxia reentered the cell cycle, moved through S phase, and eventually arrested in G2. In contrast, cells lacking Chk2 have an attenuated G2 arrest. Chk2−/− cells also reenter the cell cycle but do not accumulate in G2. To further demonstrate that Chk2 was responsible for the differences in the cell cycle profiles between these two cells, we stably expressed wild-type Chk2 in the Chk2−/− cells and a dominant-negative Chk2T68A in the Chk2+/+ cells. For a control, we stably expressed empty vector alone in Chk2−/− cells. After exposure to hypoxia and reoxygenation, we found that adding wild-type Chk2 to Chk2−/− cells restored wild-type cell cycle distributions and that the addition of the dominant-negative Chk2T68A to Chk2+/+ cells phenocopied Chk2 loss (Fig. 2A). Treatment with an empty vector as a control did not alter the cell cycle response to hypoxia and reoxygenation. A Chk2 immunoblot for protein expression in the Chk2−/− cell line verified effective gene delivery in the stably transfected cells (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Reoxygenation-induced G2 arrest is dependent on the protein kinase Chk2. (A) Cells were untreated (−) or treated with 15 h of hypoxia (H), followed by indicated hours of reoxygenation (R). Cell types are HCT116 Chk2+/+, HCT116 Chk2+/+ stably expressing Chk2T68A, HCT116 Chk2−/−, HCT116 Chk2−/− stably expressing empty vector, and HCT116 Chk2−/− stably expressing Chk2+/+. Histogram profiles of DNA content were derived from FACS analysis from PI staining. The percentage of cells in the G2 phase of the cell cycle is shown for 9 h of reoxygenation next to each histogram. (B) Confirmation of stable integration of Chk2+/+-expressing vector in HCT116 Chk2−/− cells. Total protein (50 μg) was run and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane and then probed with total Chk2 antibody and an antibody to GAPDH for loading control.

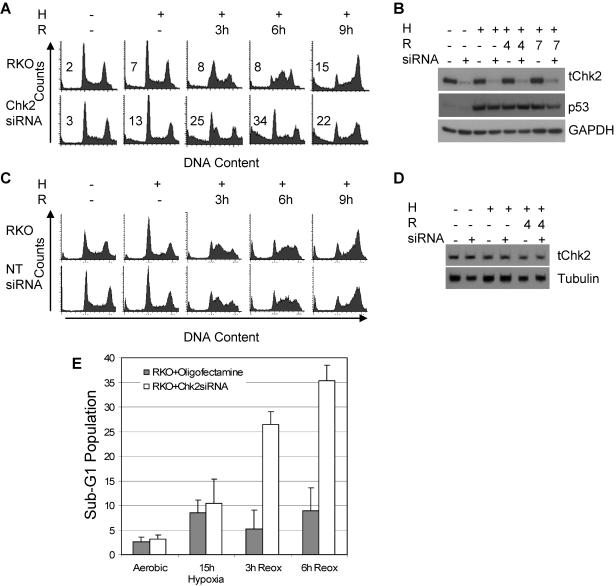

To test whether our findings were specific to the HCT116 cell line, we inhibited Chk2 in another colorectal cancer cell line, RKO, using siRNA to reduce Chk2 protein expression. RKO cells mock treated or treated with siRNA to Chk2 were exposed to hypoxia and reoxygenation and then analyzed by two-dimensional FACS (Fig. 3A). RKO cells expressing normal levels of Chk2 exhibited a reoxygenation damage response similar to that of the HCT116 Chk2+/+ cells and accumulated in the G2 phase of the cell cycle within 9 h, whereas RKO cells treated with Chk2 siRNA did not; instead, cells with reduced Chk2 protein exhibited an increase in their sub-G1 populations. After 6 h of reoxygenation, 33% of the cells treated with Chk2 siRNA were found in the sub-G1 region, compared to only 6.5% for the RKO Chk2+/+ cells (Fig. 3A and E). Chk2 immunoblots show that Chk2 siRNA treatment reduces protein expression by 95% but has no effect on either p53 or GAPDH throughout the time frame of the experiment (Fig. 3B). To confirm that the effect we observed was due to a reduction in Chk2 protein and not due to siRNA treatment alone, cells were treated with nontargeting siRNA (NT-siRNA). The response to hypoxia and reoxygenation assessed by FACS shows that siRNA treatment alone had no effect on the cell cycle (Fig. 3C). NT-siRNA had no effect on Chk2 protein levels (Fig. 3D).

FIG. 3.

Reoxygenation-induced G2 arrest after Chk2 siRNA treatment is attenuated in the RKO colon carcinoma cell line. (A) Chk2 protein knockdown in RKO colon cancer cells using Chk2 siRNA. RKO cells treated with or without Chk2 siRNA were subjected to 15 h of hypoxia (H) followed by 3, 6, or 9 h of reoxygenation (R). Shown here are histograms generated by FACS analysis of PI-stained DNA. (B) Knockdown of Chk2 protein by siRNA. Immunoblots of protein extracts from cells treated with 15 h of hypoxia followed by reoxygenation were probed with antibody to total Chk2 (tChk2), total p53, and GAPDH. (C) G2 arrest induced by Chk2 siRNA treatment was specific. NT-siRNA oligonucleotide treatment had no effect on cell cycle response to hypoxia and reoxygenation. Histograms were generated by FACS analysis of PI-stained DNA. (D) Western blots on protein extracts from NT-siRNA-treated cells subjected to hypoxia and reoxygenation probed with antibodies to total Chk2 and α-tubulin. (E) Quantification of sub-G1 populations in RKO cells treated with or without Chk2 siRNA and exposed to hypoxia and reoxygenation.

While an increase in sub-G1 population was noticeable in the HCT116 cell line as well, comparing the cell cycle profiles of the two different cell lines following hypoxia and reoxygenation shows that there is more cell death during reoxygenation in the Chk2 siRNA-treated RKO cells than the HCT116 Chk2-/- cells (Fig. 2A and 3A). The cell cycle difference between the RKO and HCT116 cells may be due to acute (RKO) versus chronic (HCT116) loss of Chk2 or to cell line-specific differences. However, in three systems, using two different cell lines, we found that in response to hypoxia/reoxygenation, loss of Chk2 leads to defective G2 arrest and an increased sub-G1 population.

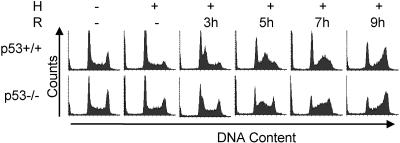

The p53 protein is not required for the hypoxia/reoxygenation damage response.

One downstream target of Chk2 that could mediate cell cycle arrest and death by apoptosis during hypoxia and reoxygenation is p53. Previous reports have shown that p53 is phosphorylated at the serine 15 residue in an ATR-dependent manner during hypoxia that is maintained in an ATM-dependent manner during reoxygenation (23, 24). Studies involving Chk2+/+ and Chk2−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts indicated that following ionizing radiation, Chk2 was required for adequate p53 stabilization (30, 61). We investigated whether the cell cycle arrest or death we observed might be linked to p53 activation, possibly through Chk2 phosphorylation of the p53 Ser 20 residue, which has been reported in in vitro kinase assays (30). We treated HCT116 p53+/+ and HCT116 p53−/− cells with hypoxia and reoxygenation and assessed the cell cycle responses. The p53−/− cells progressed from G1 to S phase more rapidly, but both cell types arrested in the G2 phase of the cell cycle approximately 9 h after reoxygenation (Fig. 4). No differences in the sub-G1 populations were observed within the time frame of the experiment. We concluded that the while the damage response we observed was dependent on Chk2, it was independent of p53.

FIG. 4.

G2 arrest is independent of p53 status. HCT116 wt and p53−/− cells were untreated (−) or treated with hypoxia (H) and reoxygenation (R). Shown here are histograms generated by FACS analysis of PI-stained DNA.

Chk2 phosphorylation is ATM dependent during hypoxia and reoxygenation.

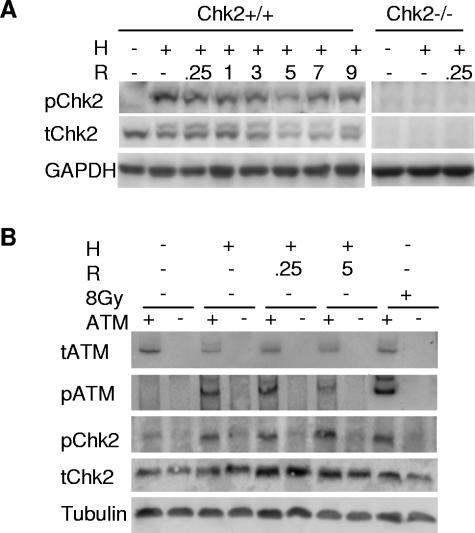

In response to ionizing radiation, ATM preferentially phosphorylates Chk2 on threonine 68 (T68) (48). To assess Chk2 phosphorylation at the T68 residue, we harvested protein from HCT116 Chk2+/+ and Chk2−/− cells exposed to 15 h of hypoxia and reoxygenation. Immunoblots of protein lysates revealed that phosphorylated Chk2 was present in total cell extracts by a mobility shift as well as by using a phospho-specific antibody, indicating that phosphorylation occurred prior to the DNA damage induced during reoxygenation (Fig. 5A). ATM and ATR exhibit different effector protein specificities in response to both UV and IR damage (28). To determine whether ATM was responsible for phosphorylating Chk2 in our system, we compared phosphorylation of Chk2 on T68 in genetically matched lymphoblastoid cell lines with and without ATM under hypoxia or reoxygenation conditions. In ATM+/+ cells, Chk2 is phosphorylated during both hypoxia and reoxygenation. On the other hand, in ATM−/− cells, Chk2 is not phosphorylated during either hypoxia or reoxygenation. Protein blots for total ATM, phospho-serine 1981 ATM, total Chk2, and phospho-threonine 68 Chk2 clearly show that Chk2 is phosphorylated in an ATM-dependent manner during hypoxia and reoxygenation (Fig. 5B). These data are consistent with recent results published by Gibson et al. that describe ATM-dependent phosphorylation of Chk2 in response to hypoxia. Although it has been suggested that ATR can also phosphorylate Chk2 in response to some types of damage, it is unlikely in this case, given that we did not observe an increase in Chk2 phosphorylation in ATM−/− cells and that in response to UV damage and IR damage, Chk2 is phosphorylated regardless of ATR status (28). We also found that ATM was phosphorylated during both hypoxia and reoxygenation. While it is not surprising that ATM is phosphorylated during reoxygenation, when damage is known to occur, ATM phosphorylation in the absence of DNA strand breaks has been demonstrated only using hypotonic buffers and drugs altering chromatin structure (4).

FIG. 5.

Chk2 phosphorylation is ATM dependent during hypoxia and reoxygenation. (A) HCT116 Chk2+/+ and Chk2−/− cells were treated with 15 h hypoxia (H) and reoxygenation (R) for the indicated hours. Protein lysates were subjected to Western blotting. Phospho-T68 Chk2 is shown in the upper panel, total Chk2 protein is shown in the middle panel, and GAPDH loading control is shown in the bottom panel. Lysates from HCT116 Chk2−/− cells failed to react with either Chk2 antibody (right panels). (B) Chk2 phosphorylation in a lymphoblastoid cell line treated with hypoxia and reoxygenation. The lymphoblastoid cell lines GM0536 (ATM+/+) and GM1526 (ATM−/−) were subjected to 15 h of hypoxia and various hours of reoxygenation. Western blots of protein lysates were probed with antibodies to phospho-S1981 ATM (pATM), total ATM (tATM), phospho-T68 Chk2 (pChk2), and α-tubulin (Tubulin).

Chk2 targets are phosphorylated during hypoxia and reoxygenation.

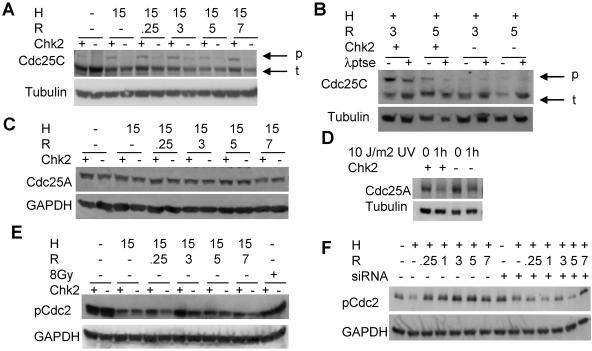

One potential target of Chk2 that has been implicated in G2 arrest is the protein phosphatase Cdc25C. Several studies implicate a Chk2 requirement for Cdc25C phosphorylation following damage by chemotherapeutics and IR in association with G2 arrest (16, 45). We subjected HCT116 Chk2+/+ and Chk2−/− cells to hypoxia and reoxygenation, harvested protein as before, and carried out an immunoblot analysis for Cdc25C (Fig. 6A). Under aerobic conditions, a single band is seen in both the HCT116 Chk2+/+ and Chk2−/− samples; however, during hypoxia and reoxygenation, we observed a Chk2-dependent shift in mobility, indicating that Cdc25C was phosphorylated and thus inactivated. To be sure that the slower migrating band in Fig. 6A was indeed the phosphorylated form of Cdc25C, we subjected Chk2+/+ and Chk2−/− protein lysates to treatment with lambda protein phosphatase (λppt), which has specific activity towards phosphorylated serine, threonine, and tyrosine. Following λppt treatment, we saw a reduction in intensity of the slower migrating band. As a loading control, the blot was probed with α-tubulin. In contrast Chk2−/− protein extracts were unchanged by phosphatase treatment (Fig. 6B). These results confirmed that Cdc25C exhibited a Chk2-dependent phosphorylation event in response to both hypoxia and reoxygenation.

FIG. 6.

Chk2 targets are phosphorylated following hypoxia and reoxygenation. (A) Cdc25C is phosphorylated during reoxygenation and is dependent on Chk2. HCT116 Chk2+/+ and Chk2−/− cells were treated with 15 h of hypoxia (H) and various times of reoxygenation (R). The top panel shows phosphorylated (p) forms migrating more slowly than total Cdc25C (t). An α-tubulin loading control is shown in the bottom panel. (B) Lambda protein phosphatase (λptse) treatment of protein extracts from HCT116 Chk2+/+ and Chk2−/− cells harvested after hypoxia and reoxygenation. (C) Cdc25A is not phosphorylated or degraded during hypoxia or reoxygenation treatment. HCT116 Chk2+/+ and Chk2−/− protein lysates from cells treated with 15 h of hypoxia and indicated times of reoxygenation were subjected to Western blotting and detection with total Cdc25A antibody, as shown in the top panel. GAPDH loading control is shown in the bottom panel. (D) Cdc25A is phosphorylated and degraded in response to UV stress. HCT116 Chk2+/+ and Chk2−/− cells were subjected to 10 J/m2 UV light. Cells were lysed after 1 h. Cdc25A was detected with total Cdc25A antibody after Western blotting, as shown in the top panel. α-Tubulin loading control is shown in the bottom panel. (E and F) Cdc2 phosphorylation during reoxygenation is Chk2 dependent. Protein lysates from HCT116 Chk2+/+ and Chk2−/− cells or from RKO cells treated with Chk2 siRNA were treated with 15 h hypoxia and indicated times of reoxygenation and were probed with phospho-specific Tyr15 Cdc2 (pCdc2) antibody after Western blotting, as shown in the upper panels. GAPDH loading control is shown in the lower panels.

Cdc25A, another Cdc25 family member, has been reported to regulate both G1 and G2 arrests (43, 44, 67). Chk1 and Chk2 have been shown to regulate Cdc25A by phosphorylation, which targets it for ubiquitin-mediated degradation by the proteosome. Once it is degraded, Cdc25A is unable to dephosphorylate Cdk2, which in turn cannot bind cyclins A and D, and cells do not progress from the G1 phase to the S phase of the cell cycle (37, 55). To determine whether Cdc25A had a role in hypoxia/reoxygenation-mediated damage response, protein lysates were collected following exposure to hypoxia and reoxygenation, and an immunoblot analysis was carried out for total Cdc25A (Fig. 6C). We found Cdc25A protein stability was unaffected following either hypoxia or reoxygenation treatment. To confirm that HCT116 cells were capable of signaling to Cdc25A, we exposed cells to 10 J/m2 UV and probed for Cdc25A following Western blotting. We found Cdc25A degraded following UV exposure in both HCT116 wt and Chk2−/− cells (6D). Based on these results, we concluded that Chk2 did not phosphorylate Cdc25A and that Cdc25A was not contributing to the arrest phenotypes under conditions of hypoxia or reoxygenation.

Ultimately, the Cdc2/cyclin B complex regulates progression from G2 to mitosis. Complex activation occurs following the removal of inhibitory phosphorylation at threonine 14 and tyrosine 15. A positive feedback loop facilitates Cdc2 dephosphorylation by Cdc25C, ensuring the progression to mitosis in undamaged cells (34, 35). However, during stress, Cdc25C activity is reduced through sequestration in the cytoplasm, and Cdc2 activity is inhibited via sustained phosphorylation (52). To determine the effect on Cdc2 following hypoxia and reoxygenation, we compared Cdc2 phosphorylation status in HCT116 Chk2+/+ and Chk2−/− cells. By immunoblotting, using a phospho-specific Tyr15 antibody against Cdc2, we found that Cdc2 was indeed phosphorylated during reoxygenation in a Chk2-dependent manner (Fig. 6E and F). In response to reoxygenation, Cdc2 phosphorylation in HCT116 Chk2+/+ cells is induced, particularly by 3 h, compared to that in response to hypoxia alone. In Chk2−/− cells, however, Cdc2 phosphorylation is unaffected during reoxygenation. Using Chk2 siRNA to knock down protein expression in RKO cells, we also found that Cdc2 phosphorylation is maintained at a higher level in a Chk2-dependent manner (Fig. 6F). RKO cells transfected with Chk2 siRNA had reduced phosphorylation during reoxygenation. Therefore, Chk2 appears to be controlling a G2 arrest through the regulation of Cdc25C activity and Cdc2.

Survival is impaired in Chk2−/− cells following hypoxia and reoxygenation.

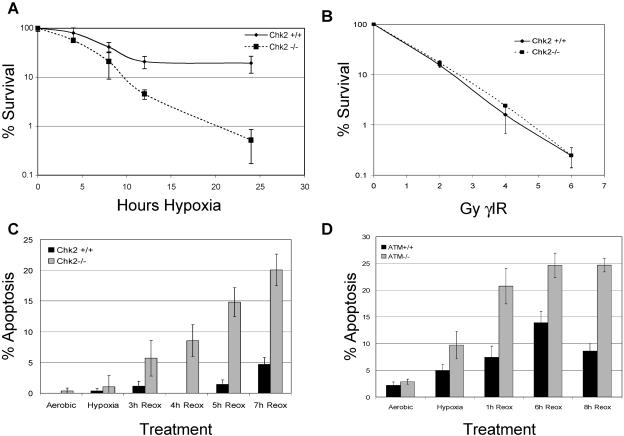

To further characterize the Chk2-mediated damage response, we assessed the effects of hypoxia/reoxygenation and gamma IR on colony survival in both HCT116 Chk2+/+ and Chk2−/− cells. For reoxygenation studies, 500 cells of each type were plated in triplicate and exposed to a range of hypoxia treatments and allowed to grow undisturbed for 14 days (Fig. 7A). Chk2−/− cells were significantly more sensitive to the stress of hypoxia/reoxygenation, with less than 1% surviving after 24 h of hypoxia and 2 weeks of reoxygenation, while 51% of the Chk2+/+ cells survived after the same treatment. In contrast, both Chk2+/+ and Chk2−/− cells exhibited similar sensitivities to 2, 4, 6, and 8 Gy of gamma IR treatment (Fig. 7B). These data demonstrate significant differences in the biological response to gamma IR compared to the stress of hypoxia and reoxygenation that is mediated by Chk2.

FIG. 7.

Chk2−/− cells are sensitive to hypoxia and reoxygenation. (A) Colony-forming efficiency. Decreased survival of HCT116 Chk2−/− cells during reoxygenation is proportional to length of exposure to hypoxia. HCT116 Chk2+/+ and Chk2−/− cells were untreated or treated with hypoxia for 4, 8, 12, or 24 h and then incubated undisturbed for 2 weeks. Colonies were stained with crystal violet and counted. Results are expressed in log values. (B) Chk2+/+ and Chk2−/− cells are equally as sensitive to ionizing radiation. HCT116 Chk2+/+ and Chk2−/− cells were subjected to 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 Gy gamma irradiation (γIR) and then allowed to grow undisturbed for 2 weeks. Colonies were stained with crystal violet and counted. Colony numbers are expressed in log values. (C) Increased apoptosis in Chk2−/− cells during reoxygenation. HCT116 Chk2+/+ and Chk2−/− cells were either untreated or placed in hypoxia for 15 h. Upon reoxygenation, cells were stained with Hoechst 33342 and PI. Nuclear morphology was assessed for each condition. Graphs are presented as the percentages of apoptotic cells in the total population. (D) Cells deficient in ATM are sensitive to reoxygenation. ATM+/+ (YZ3) or ATM−/− (pEBS) cells were treated with 15 h of hypoxia and then stained with Hoechst 33342 and PI at the indicated times. Results are reported as the percentages of apoptotic cells in the total population.

We speculated that the increase in sub-G1 content seen in our FACS analysis and the decrease in colony survival of Chk2−/− cells might be due in part to apoptosis. To test this hypothesis, we stained cells with Hoechst 3342 and PI to quantify apoptosis. HCT116 Chk2+/+ and Chk2−/− cells were subjected to hypoxia and reoxygenation for the indicated times (Fig. 7C). We found that cells lacking Chk2 were at least five times more sensitive to the stress of reoxygenation than Chk2+/+ cells. Since Chk2 is dependent on ATM for phosphorylation during hypoxia and reoxygenation, we also looked at apoptosis in cells with or without ATM. We observed increased cell death in ATM null fibroblasts (Fig. 7D), reconfirming the link between ATM and Chk2 in the reoxygenation damage response.

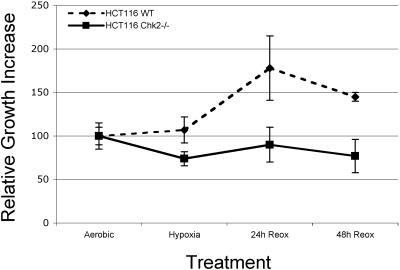

We further investigated the differences in survival between HCT116 Chk2+/+ and Chk2−/− cells during early reoxygenation time points. HCT116 Chk2+/+ and Chk2−/− cells stably infected with EYFP and ECFP, respectively, were mixed in equal numbers, plated on chamber slides, and then exposed to hypoxia and reoxygenation. Following hypoxia and 1 or 2 days of reoxygenation, we counted the number of surviving fluorescent cells in each population (Fig. 8A). Three fields of more than 200 cells were counted for each cell line and each time point. After 24 h of reoxygenation, the HCT116 Chk2+/+ cell population was nearly double the HCT116 Chk2−/− cell population. Together, these data suggest that the Chk2-mediated G2 arrest following hypoxia and reoxygenation plays an important role in maintaining cell survival.

FIG. 8.

Chk2+/+ cells have a survival advantage during reoxygenation. HCT116 Chk2+/+ and Chk2−/− cells stably expressing EYFP and ECFP were mixed in equal numbers and plated onto slides and then either left untreated, treated with hypoxia overnight, or treated and then allowed to grow for 1 or 2 days under normal culture conditions. Blue and yellow cells were counted at each time point. Cell numbers relative to the starting population are plotted above.

DNA damage in HCT116 cells is attenuated by ROS scavenger, NAC.

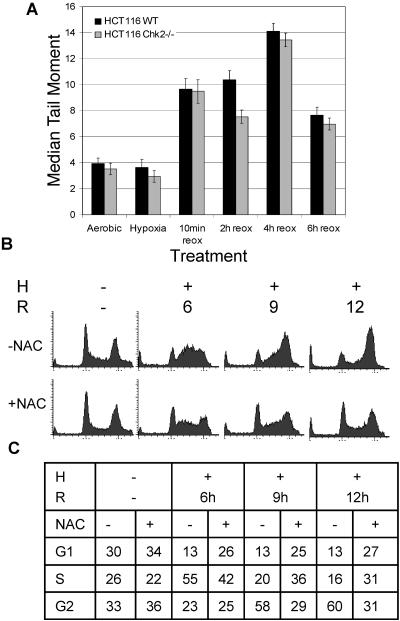

In an effort to determine the mechanism by which hypoxia and reoxygenation result in the G2 arrest phenotype, we investigated damage response more thoroughly. First, we looked at the DNA damage. Previously published studies indicated that upon removal from hypoxia, cellular DNA damage occurs nearly instantaneously (24). For a more extensive study of this damage, we performed a comet assay on cells exposed to hypoxia and reoxygenation (Fig. 9A). In agreement with previously published data, we found that no increase in DNA damage was detectable during hypoxia treatment. However, during reoxygenation, DNA damage was sustained and increased for approximately 4 h before repair could be detected. ROS generation following reoxygenation after periods of ischemia or hypoxia is known to result in DNA damage (8, 14, 24, 41, 62, 74). To determine whether damage due to ROS generation during reoxygenation was responsible for the G2 arrest phenotype, we treated cells with NAC before exposure to hypoxia and reoxygenation (Fig. 9B and C). Cell cycle distributions remained almost normal in the NAC-treated cells, with 29% of cells in the G2 phase of the cell cycle after 9 h of reoxygenation, while 58% of the untreated cells accumulated in the G2 phase of the cell cycle after the same amount of time. Cells treated with NAC displayed a reduced G2 arrest response to hypoxia and reoxygenation, confirming that the damage response was due to ROS generation.

FIG. 9.

Reoxygenation-dependent damage response is attenuated by ROS scavenger NAC. (A) The comet assay detects increasing damage during reoxygenation in HCT116 Chk2+/+ and Chk2−/− cells. Hypoxic samples were trypsinized and lysed under hypoxia conditions. Reoxygenation samples were harvested after indicated times. (B) HCT116 cells were treated with 10 mM NAC prior to hypoxia (H) and reoxygenation (R). After fixation, cell cycle distributions were assessed by FACS analysis of PI-stained DNA.

DISCUSSION

Using genetically matched cells as well as protein knockdown by siRNA in RKO cells, we demonstrated that Chk2 is responsible for mediating the damage response to reoxygenation. Loss of Chk2 resulted in reduced phosphorylation of its downstream targets, Cdc25C and Cdc2, and resulted in attenuated G2 arrest, increased apoptosis, and decreased colony survival. Our data suggest that checkpoint loss results in sensitivity rather than resistance to death mechanisms.

Recently, in response to damage caused by 5-fluorouracil, it was demonstrated that loss of Chk1, and thus loss of a checkpoint, resulted in increased sensitivity to apoptosis. FACS profiles showed that cells failed to reach 4N DNA content and instead underwent apoptosis (68). Furthermore, Chk2 loss is not associated with radioresistance in human cells (36, 70). In response to gamma IR, HEK-293 cells with reduced Chk2 protein levels were more sensitive to DNA damage-induced apoptosis, despite being unable to stabilize p53 protein above control levels (70). Taken together, these data support our findings that loss of a checkpoint can result in increased sensitivity to stress.

On the other hand, a recent report by Jallepalli et al. found that loss of Chk2 did not affect the cell cycle response to ionizing radiation in HCT116 cells (36). Regardless of Chk2 status, p53 was found to be both stabilized and phosphorylated on serine 20 in their system. Our findings, however, imply a significant regulatory role for Chk2 following reoxygenation, underscoring the fact that the tumor-specific stress of hypoxia/reoxygenation evokes a damage response that is not equivalent to the damage response induced by ionizing radiation. Like Jallepalli et al., we also found that HCT116 Chk2+/+ and Chk2−/− cells exposed respond to gamma IR damage in similar manners as both cell lines reached G2 arrest 8 h following treatment (36). These differences in cell cycle checkpoint responses highlight a novel distinction between gamma IR-induced damage, in which G2 arrest is Chk2 independent, versus reoxygenation-induced damage, which results in a Chk2-dependent G2 arrest.

One thing to consider when interpreting these results is that both HCT116 and RKO cells are derived from colon cancer cells and are deficient in mismatch repair (MMR) genes. MMR gene mutations or epigenetic silencing is found in a variety of hereditary and sporadic cancers (10, 18, 39). MMR gene defects are associated with decreased sensitivity to DNA damaging drugs, such as cisplatin, doxorubicin, and 5-fluorouracil (13, 17), but show increased sensitivity to agents that disrupt DNA replication by inhibition of DNA polymerase (60). In our system, where DNA replication is stalled during S phase, followed by ROS-induced DNA damage, these defects may have some role in the baseline apoptosis seen in cells proficient in Chk2.

In our system, cells with intact Chk2 have a survival advantage over cells lacking this important checkpoint protein. By Western analysis, we found Cdc25C to be phosphorylated in a Chk2-dependent manner during both hypoxia and reoxygenation. Chk2 was also required for the maintenance of the inhibitory phosphorylation at Tyr15 of Cdc2. Both HCT116 Chk2−/− cells and RKO cells treated with Chk2 siRNA exhibited decreased Cdc2 phosphorylation during reoxygenation. Loss of phosphatase activity of another member of the Cdc25 family, Cdc25A, has also been shown to regulate G2 arrest (43, 44, 67). However, in the systems described here, no changes in phosphorylation or abundance of Cdc25A were observed during hypoxia/reoxygenation studies, although Cdc25A degradation was induced by exposure to UV irradiation. Cdc2 was hypophosphorylated during hypoxia in both HCT116 Chk2+/+ and HCT116 Chk2−/− cells and hyperphosphorylated in Chk2-proficient cells but not Chk2-deficient cells during reoxygenation, indicating that cells were arrested in the G2 phase of the cell cycle in a Chk2-dependent manner during reoxygenation only. This result indicates that the G2 arrest found under hypoxic conditions may be through a different mechanism.

A particularly intriguing result from this study was that ATM was phosphorylated and active despite the absence of DNA strand breaks during hypoxia. That ATM was phosphorylated during hypoxia was somewhat surprising since DNA strand breaks, thought to be required for induction of this phosphorylation event, are undetectable by comet assay during hypoxia. In support of this, there is recent evidence that UV-induced stalled replication forks result in ATM-dependent phosphorylation of Chk2, although ATM phosphorylation, in this case, was not specifically addressed (28). Additionally, a recent study by Gibson et al. describes ATM- and not ATR-dependent phosphorylation of Chk2 during hypoxia treatment in MCF-7 cells (19). Further supporting our finding that ATM is phosphorylated in the absence of damage is a report that phosphorylated histone H2AX has also been found under hypoxic conditions (24). ATM oligomer dissociation and autophosphorylation can be induced both by exposure to hypotonic solutions and by changes in chromatin structure as well as by inhibition of protein phosphatase 2A interaction with ATM (4, 20). These data support a model in which hypoxia is capable of inducing phosphorylation of ATM in the absence of strand breaks, possibly by structural changes in chromatin that are found when S-phase cells form stalled replication forks following treatment with hypoxia (25).

By comet assay, we detected increasing DNA damage during the first several hours of reoxygenation. One possibility is that due to alterations in gene and protein expression during 15 h of severe hypoxia, cells are incapable of either immediate damage repair or protecting from damage. A second possibility is that ROS generation during reoxygenation leads to an extended period of DNA damage. In support of this, ischemia and reperfusion studies have shown that extending the period of ischemia results in increased ROS formation and leads to increased p53 independent apoptosis, which can be attenuated by superoxide dismutase pretreatment (14). Confirming that ROS generation contributed to the G2 arrest, we showed that pretreatment of cells with NAC was effective in reducing the G2 arrest response to reoxygenation. Several other reports have shown that hypoxia and reoxygenation induce ROS formation and that hypoxia actually decreases ROS levels (62, 74). The use of NAC, a chemical ROS scavenger, attenuated p53 phosphorylation of Ser 15 during reoxygenation but not phosphorylation at this residue during hypoxia, further supporting the model for ROS formation during reoxygenation causing DNA damage (24).

A recent publication by Bartkova et al. suggests that in early tumors, activated oncogenes causing unscheduled DNA replication result in a damage response that activates ATM and Chk2, among other proteins. They hypothesize that the acquisition of further mutations allows the cells to overcome the damage response, adding to the genomic instability of the tumor (7). However, because of the limited diffusion distance of oxygen in tissues, hypoxia is also thought to be an early stress in the developing tumor. As we have shown here, hypoxia and reoxygenation have an important and often overlooked role, influencing the DNA damage response, proliferation, cell cycle, and survival. In turn, these factors influence the tumor response in that they determine the efficacy of radiotherapy and chemotherapy (11, 66). Potentially, loss of Chk2, and thus loss of a checkpoint, could result in increased genomic instability in cells as they acquire additional mutations. Perhaps it is the combination of activated oncogenes and hypoxia/reoxygenation that contributes to tumorigenesis and genomic instability rather than either stress alone.

The correlation between tumor hypoxia and aggression, low apoptotic index, and overall poor prognosis has been well documented (31-33). The loss of checkpoint response resulting from mutations in genes involved in the detection and repair of DNA is likely to account for some of these phenomena. Together, these perturbations in the normal cellular processes and fluctuating oxygen tensions exert a selective pressure on the cells, allowing for the expansion of mutant populations. Our data strongly indicate that Chk2 is essential in responding to hypoxia and reoxygenation and controls activation of downstream targets responsible for activation of G2 arrest and DNA repair.

This work not only is an important addition to the understanding of how the tumor suppressor Chk2 responds to oxidative damage but also may help in understanding how cells respond to changes in oxygen tension that occur under other pathophysiologic conditions.

Acknowledgments

We kindly thank Bert Vogelstein and Fred Bunz for HCT116 Chk2+/+ and HCT116 Chk2−/− cell lines, Michael Kastan for the GM1526 and GM536 cell lines, and Yoseph Shiloh for the pEBS and YZ3 cell lines.

This work was supported by NIH grant CA 88480.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abraham, R. T. 2001. Cell cycle checkpoint signaling through the ATM and ATR kinases. Genes Dev. 15:2177-2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adamson, A. W., D. I. Beardsley, W. J. Kim, Y. Gao, R. Baskaran, and K. D. Brown. 2005. Methylator-induced, mismatch repair-dependent G2 arrest is activated through Chk1 and Chk2. Mol. Biol. Cell 16:1513-1526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahn, J. Y., J. K. Schwarz, H. Piwnica-Worms, and C. E. Canman. 2000. Threonine 68 phosphorylation by ataxia telangiectasia mutated is required for efficient activation of Chk2 in response to ionizing radiation. Cancer Res. 60:5934-5936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakkenist, C. J., and M. B. Kastan. 2003. DNA damage activates ATM through intermolecular autophosphorylation and dimer dissociation. Nature 421:499-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartek, J., J. Falck, and J. Lukas. 2001. CHK2 kinase-a busy messenger. Nat Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2:877-886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bartkova, J., P. Guldberg, K. Gronbaek, K. Koed, H. Primdahl, K. Moller, J. Lukas, T. F. Orntoft, and J. Bartek. 2004. Aberrations of the Chk2 tumour suppressor in advanced urinary bladder cancer. Oncogene 23:8545-8551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bartkova, J., Z. Horejsi, K. Koed, A. Kramer, F. Tort, K. Zieger, P. Guldberg, M. Sehested, J. M. Nesland, C. Lukas, T. Orntoft, J. Lukas, and J. Bartek. 2005. DNA damage response as a candidate anti-cancer barrier in early human tumorigenesis. Nature 434:864-870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barzilai, A., and K. Yamamoto. 2004. DNA damage responses to oxidative stress. DNA Repair (Amsterdam) 3:1109-1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bertoni, F., A. M. Codegoni, D. Furlan, M. G. Tibiletti, C. Capella, and M. Broggini. 1999. CHK1 frameshift mutations in genetically unstable colorectal and endometrial cancers. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 26:176-180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyer, J. C., A. Umar, J. I. Risinger, J. R. Lipford, M. Kane, S. Yin, J. C. Barrett, R. D. Kolodner, and T. A. Kunkel. 1995. Microsatellite instability, mismatch repair deficiency, and genetic defects in human cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 55:6063-6070. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown, J. M. 2002. Tumor microenvironment and the response to anticancer therapy. Cancer Biol. Ther. 1:453-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Canman, C. E., D. S. Lim, K. A. Cimprich, Y. Taya, K. Tamai, K. Sakaguchi, E. Appella, M. B. Kastan, and J. D. Siliciano. 1998. Activation of the ATM kinase by ionizing radiation and phosphorylation of p53. Science 281:1677-1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carethers, J. M., D. P. Chauhan, D. Fink, S. Nebel, R. S. Bresalier, S. B. Howell, and C. R. Boland. 1999. Mismatch repair proficiency and in vitro response to 5-fluorouracil. Gastroenterology 117:123-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chien, C. T., P. H. Lee, C. F. Chen, M. C. Ma, M. K. Lai, and S. M. Hsu. 2001. De novo demonstration and co-localization of free-radical production and apoptosis formation in rat kidney subjected to ischemia/reperfusion. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 12:973-982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cliby, W. A., C. J. Roberts, K. A. Cimprich, C. M. Stringer, J. R. Lamb, S. L. Schreiber, and S. H. Friend. 1998. Overexpression of a kinase-inactive ATR protein causes sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents and defects in cell cycle checkpoints. EMBO J. 17:159-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deep, G., R. P. Singh, C. Agarwal, D. J. Kroll, and R. Agarwal. 3 October 2005, posting date. Silymarin and silibinin cause G1 and G2-M cell cycle arrest via distinct circuitries in human prostate cancer PC3 cells: a comparison of flavanone silibinin with flavanolignan mixture silymarin. Oncogene [Online.] doi: 10.1038/sj.onc. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Drummond, J. T., A. Anthoney, R. Brown, and P. Modrich. 1996. Cisplatin and adriamycin resistance are associated with MutLalpha and mismatch repair deficiency in an ovarian tumor cell line. J. Biol. Chem. 271:19645-19648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fleisher, A. S., M. Esteller, G. Tamura, A. Rashid, O. C. Stine, J. Yin, T. T. Zou, J. M. Abraham, D. Kong, S. Nishizuka, S. P. James, K. T. Wilson, J. G. Herman, and S. J. Meltzer. 2001. Hypermethylation of the hMLH1 gene promoter is associated with microsatellite instability in early human gastric neoplasia. Oncogene 20:329-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibson, S. L., R. S. Bindra, and P. M. Glazer. 2005. Hypoxia-induced phosphorylation of Chk2 in an ataxia telangiectasia mutated-dependent manner. Cancer Res. 65:10734-10741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goodarzi, A. A., J. C. Jonnalagadda, P. Douglas, D. Young, R. Ye, G. B. Moorhead, S. P. Lees-Miller, and K. K. Khanna. 2004. Autophosphorylation of ataxia-telangiectasia mutated is regulated by protein phosphatase 2A. EMBO J. 23:4451-4461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Graeber, T. G., J. F. Peterson, M. Tsai, K. Monica, A. J. Fornace, Jr., and A. J. Giaccia. 1994. Hypoxia induces accumulation of p53 protein, but activation of a G1-phase checkpoint by low-oxygen conditions is independent of p53 status. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:6264-6277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Green, S. L., R. A. Freiberg, and A. J. Giaccia. 2001. p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 regulate cell cycle reentry after hypoxic stress but are not necessary for hypoxia-induced arrest. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:1196-1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hammond, E. M., N. C. Denko, M. J. Dorie, R. T. Abraham, and A. J. Giaccia. 2002. Hypoxia links ATR and p53 through replication arrest. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:1834-1843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hammond, E. M., M. J. Dorie, and A. J. Giaccia. 2003. ATR/ATM targets are phosphorylated by ATR in response to hypoxia and ATM in response to reoxygenation. J. Biol. Chem. 278:12207-12213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hammond, E. M., and A. J. Giaccia. 2004. The role of ATM and ATR in the cellular response to hypoxia and re-oxygenation. DNA Repair (Amsterdam) 3:1117-1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hammond, E. M., S. L. Green, and A. J. Giaccia. 2003. Comparison of hypoxia-induced replication arrest with hydroxyurea and aphidicolin-induced arrest. Mutat. Res. 532:205-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reference deleted.

- 28.Helt, C. E., W. A. Cliby, P. C. Keng, R. A. Bambara, and M. A. O'Reilly. 2005. Ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) and ATM and Rad3-related protein exhibit selective target specificities in response to different forms of DNA damage. J. Biol. Chem. 280:1186-1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hirao, A., A. Cheung, G. Duncan, P. M. Girard, A. J. Elia, A. Wakeham, H. Okada, T. Sarkissian, J. A. Wong, T. Sakai, E. De Stanchina, R. G. Bristow, T. Suda, S. W. Lowe, P. A. Jeggo, S. J. Elledge, and T. W. Mak. 2002. Chk2 is a tumor suppressor that regulates apoptosis in both an ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM)-dependent and an ATM-independent manner. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:6521-6532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hirao, A., Y. Y. Kong, S. Matsuoka, A. Wakeham, J. Ruland, H. Yoshida, D. Liu, S. J. Elledge, and T. W. Mak. 2000. DNA damage-induced activation of p53 by the checkpoint kinase Chk2. Science 287:1824-1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hockel, M., C. Knoop, K. Schlenger, B. Vorndran, E. Baussmann, M. Mitze, P. G. Knapstein, and P. Vaupel. 1993. Intratumoral pO2 predicts survival in advanced cancer of the uterine cervix. Radiother. Oncol. 26:45-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hockel, M., K. Schlenger, B. Aral, M. Mitze, U. Schaffer, and P. Vaupel. 1996. Association between tumor hypoxia and malignant progression in advanced cancer of the uterine cervix. Cancer Res. 56:4509-4515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hockel, M., K. Schlenger, S. Hockel, and P. Vaupel. 1999. Hypoxic cervical cancers with low apoptotic index are highly aggressive. Cancer Res. 59:4525-4528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoffmann, I., P. R. Clarke, M. J. Marcote, E. Karsenti, and G. Draetta. 1993. Phosphorylation and activation of human cdc25-C by cdc2-cyclin B and its involvement in the self-amplification of MPF at mitosis. EMBO J. 12:53-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Izumi, T., and J. L. Maller. 1993. Elimination of cdc2 phosphorylation sites in the cdc25 phosphatase blocks initiation of M-phase. Mol. Biol. Cell 4:1337-1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jallepalli, P. V., C. Lengauer, B. Vogelstein, and F. Bunz. 2003. The Chk2 tumor suppressor is not required for p53 responses in human cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 278:20475-20479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jinno, S., K. Suto, A. Nagata, M. Igarashi, Y. Kanaoka, H. Nojima, and H. Okayama. 1994. Cdc25A is a novel phosphatase functioning early in the cell cycle. EMBO J. 13:1549-1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krtolica, A., and J. W. Ludlow. 1996. Hypoxia arrests ovarian carcinoma cell cycle progression, but invasion is unaffected. Cancer Res. 56:1168-1173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leach, F. S., N. C. Nicolaides, N. Papadopoulos, B. Liu, J. Jen, R. Parsons, P. Peltomaki, P. Sistonen, L. A. Aaltonen, M. Nystrom-Lahti, et al. 1993. Mutations of a mutS homolog in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Cell 75:1215-1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee, J. S., K. M. Collins, A. L. Brown, C. H. Lee, and J. H. Chung. 2000. hCds1-mediated phosphorylation of BRCA1 regulates the DNA damage response. Nature 404:201-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li, C., M. M. Wright, and R. M. Jackson. 2002. Reactive species mediated injury of human lung epithelial cells after hypoxia-reoxygenation. Exp. Lung Res. 28:373-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu, Q., S. Guntuku, X. S. Cui, S. Matsuoka, D. Cortez, K. Tamai, G. Luo, S. Carattini-Rivera, F. DeMayo, A. Bradley, L. A. Donehower, and S. J. Elledge. 2000. Chk1 is an essential kinase that is regulated by Atr and required for the G(2)/M DNA damage checkpoint. Genes Dev. 14:1448-1459. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mailand, N., J. Falck, C. Lukas, R. G. Syljuasen, M. Welcker, J. Bartek, and J. Lukas. 2000. Rapid destruction of human Cdc25A in response to DNA damage. Science 288:1425-1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mailand, N., A. V. Podtelejnikov, A. Groth, M. Mann, J. Bartek, and J. Lukas. 2002. Regulation of G(2)/M events by Cdc25A through phosphorylation-dependent modulation of its stability. EMBO J. 21:5911-5920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matsuoka, S., M. Huang, and S. J. Elledge. 1998. Linkage of ATM to cell cycle regulation by the Chk2 protein kinase. Science 282:1893-1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matsuoka, S., T. Nakagawa, A. Masuda, N. Haruki, S. J. Elledge, and T. Takahashi. 2001. Reduced expression and impaired kinase activity of a Chk2 mutant identified in human lung cancer. Cancer Res. 61:5362-5365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Matsuoka, S., G. Rotman, A. Ogawa, Y. Shiloh, K. Tamai, and S. J. Elledge. 2000. Ataxia telangiectasia-mutated phosphorylates Chk2 in vivo and in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:10389-10394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Melchionna, R., X. B. Chen, A. Blasina, and C. H. McGowan. 2000. Threonine 68 is required for radiation-induced phosphorylation and activation of Cds1. Nat. Cell Biol. 2:762-765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Menoyo, A., H. Alazzouzi, E. Espin, M. Armengol, H. Yamamoto, and S. Schwartz, Jr. 2001. Somatic mutations in the DNA damage-response genes ATR and CHK1 in sporadic stomach tumors with microsatellite instability. Cancer Res. 61:7727-7730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nurse, P. 1990. Universal control mechanism regulating onset of M-phase. Nature 344:503-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Olive, P. L., J. P. Banath, and R. E. Durand. 1990. Heterogeneity in radiation-induced DNA damage and repair in tumor and normal cells measured using the “comet” assay. Radiat. Res. 122:86-94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Peng, C. Y., P. R. Graves, R. S. Thoma, Z. Wu, A. S. Shaw, and H. Piwnica-Worms. 1997. Mitotic and G2 checkpoint control: regulation of 14-3-3 protein binding by phosphorylation of Cdc25C on serine-216. Science 277:1501-1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saito, A., C. M. Maier, P. Narasimhan, T. Nishi, Y. S. Song, F. Yu, J. Liu, Y. S. Lee, C. Nito, H. Kamada, R. L. Dodd, L. B. Hsieh, B. Hassid, E. E. Kim, M. Gonzalez, and P. H. Chan. 2005. Oxidative stress and neuronal death/survival signaling in cerebral ischemia. Mol. Neurobiol. 31:105-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Seim, J., P. Graff, O. Amellem, K. S. Landsverk, T. Stokke, and E. O. Pettersen. 2003. Hypoxia-induced irreversible S-phase arrest involves down-regulation of cyclin A. Cell Prolif. 36:321-332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sexl, V., J. A. Diehl, C. J. Sherr, R. Ashmun, D. Beach, and M. F. Roussel. 1999. A rate limiting function of cdc25A for S phase entry inversely correlates with tyrosine dephosphorylation of Cdk2. Oncogene 18:573-582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shah-Yukich, A. A., and A. C. Nelson. 1988. Characterization of solid tumor microvasculature: a three-dimensional analysis using the polymer casting technique. Lab Investig. 58:236-244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shweiki, D., A. Itin, D. Soffer, and E. Keshet. 1992. Vascular endothelial growth factor induced by hypoxia may mediate hypoxia-initiated angiogenesis. Nature 359:843-845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Staalesen, V., J. Falck, S. Geisler, J. Bartkova, A. L. Borresen-Dale, J. Lukas, J. R. Lillehaug, J. Bartek, and P. E. Lonning. 2004. Alternative splicing and mutation status of CHEK2 in stage III breast cancer. Oncogene 23:8535-8544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sugawara, T., M. Fujimura, N. Noshita, G. W. Kim, A. Saito, T. Hayashi, P. Narasimhan, C. M. Maier, and P. H. Chan. 2004. Neuronal death/survival signaling pathways in cerebral ischemia. NeuroRx 1:17-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Takahashi, T., Z. Min, I. Uchida, M. Arita, Y. Watanabe, M. Koi, and H. Hemmi. 2005. Hypersensitivity in DNA mismatch repair-deficient colon carcinoma cells to DNA polymerase reaction inhibitors. Cancer Lett. 220:85-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Takai, H., K. Naka, Y. Okada, M. Watanabe, N. Harada, S. Saito, C. W. Anderson, E. Appella, M. Nakanishi, H. Suzuki, K. Nagashima, H. Sawa, K. Ikeda, and N. Motoyama. 2002. Chk2-deficient mice exhibit radioresistance and defective p53-mediated transcription. EMBO J. 21:5195-5205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Therade-Matharan, S., E. Laemmel, J. Duranteau, and E. Vicaut. 2004. Reoxygenation after hypoxia and glucose depletion causes reactive oxygen species production by mitochondria in HUVEC. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 287:R1037-R1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Thomlinson, R. H., and L. H. Gray. 1955. The histological structure of some human lung cancers and the possible implications for radiotherapy. Br. J. Cancer 9:539-549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tomida, A., and T. Tsuruo. 1999. Drug resistance mediated by cellular stress response to the microenvironment of solid tumors. Anticancer Drug Des. 14:169-177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vassileva, V., A. Millar, L. Briollais, W. Chapman, and B. Bapat. 2002. Genes involved in DNA repair are mutational targets in endometrial cancers with microsatellite instability. Cancer Res. 62:4095-4099. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vaupel, P., and M. Hockel. 2000. Blood supply, oxygenation status and metabolic micromilieu of breast cancers: characterization and therapeutic relevance. Int. J. Oncol. 17:869-879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xiao, Z., Z. Chen, A. H. Gunasekera, T. J. Sowin, S. H. Rosenberg, S. Fesik, and H. Zhang. 2003. Chk1 mediates S and G2 arrests through Cdc25A degradation in response to DNA-damaging agents. J. Biol. Chem. 278:21767-21773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xiao, Z., J. Xue, T. J. Sowin, S. H. Rosenberg, and H. Zhang. 2005. A novel mechanism of checkpoint abrogation conferred by Chk1 downregulation. Oncogene 24:1403-1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yang, W., and E. R. Block. 1995. Effect of hypoxia and reoxygenation on the formation and release of reactive oxygen species by porcine pulmonary artery endothelial cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 164:414-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yu, Q., J. H. Rose, H. Zhang, and Y. Pommier. 2001. Antisense inhibition of Chk2/hCds1 expression attenuates DNA damage-induced S and G2 checkpoints and enhances apoptotic activity in HEK-293 cells. FEBS Lett. 505:7-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zeman, E. M., D. P. Calkins, J. M. Cline, D. E. Thrall, and J. A. Raleigh. 1993. The relationship between proliferative and oxygenation status in spontaneous canine tumors. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 27:891-898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang, J., H. Willers, Z. Feng, J. C. Ghosh, S. Kim, D. T. Weaver, J. H. Chung, S. N. Powell, and F. Xia. 2004. Chk2 phosphorylation of BRCA1 regulates DNA double-strand break repair. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:708-718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ziv, Y., A. Bar-Shira, I. Pecker, P. Russell, T. J. Jorgensen, I. Tsarfati, and Y. Shiloh. 1997. Recombinant ATM protein complements the cellular A-T phenotype. Oncogene 15:159-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zulueta, J. J., R. Sawhney, F. S. Yu, C. C. Cote, and P. M. Hassoun. 1997. Intracellular generation of reactive oxygen species in endothelial cells exposed to anoxia-reoxygenation. Am. J. Physiol. 272:L897-902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]