Abstract

CrkRS is a Cdc2-related protein kinase that contains an arginine- and serine-rich (SR) domain, a characteristic of the SR protein family of splicing factors, and is proposed to be involved in RNA processing. However, whether it acts together with a cyclin and at which steps it may function to regulate RNA processing are not clear. Here, we report that CrkRS interacts with cyclin L1 and cyclin L2, and thus rename it as the long form of cyclin-dependent kinase 12 (CDK12L). A shorter isoform of CDK12, CDK12S, that differs from CDK12L only at the carboxyl end, was also identified. Both isoforms associate with cyclin L1 through interactions mediated by the kinase domain and the cyclin domain, suggesting a bona fide CDK/cyclin partnership. Furthermore, CDK12 isoforms alter the splicing pattern of an E1a minigene, and the effect is potentiated by the cyclin domain of cyclin L1. When expression of CDK12 isoforms is perturbed by small interfering RNAs, a reversal of the splicing choices is observed. The activity of CDK12 on splicing is counteracted by SF2/ASF and SC35, but not by SRp40, SRp55, and SRp75. Together, our findings indicate that CDK12 and cyclin L1/L2 are cyclin-dependent kinase and cyclin partners and regulate alternative splicing.

It is estimated that fewer than 30,000 genes are present in the human genome (13). The heterogeneity generated by this number of genes is not enough to account for the complexity that specifies human organs. One way to create more proteomic variations is through alternative splicing (2, 21). About 38 to 74% of human genes are subject to alternative splicing (3, 14, 15), and mutations that affect splicing patterns are the underlying causes of some cancers and neurodegenerative diseases (10, 29). It is estimated that ∼15% of disease-causing mutations in human genes involve misregulation of alternative splicing (25). Thus, unraveling the pathways and the molecules involved in alternative splicing is crucial to an understanding of various intricate cellular functions and for the management of human diseases.

Although cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) and their associated cyclins are pivotal for cell cycle progression and RNA transcription (23), evidence has emerged that they also engage in the regulation of RNA splicing (19, 27). For example, CDK11p110 colocalizes with the general splicing factor RNPS1 (20) and serine- and arginine-rich (SR) proteins, such as 9G8 (12). Moreover, depletion of CDK11p110 immune complex impedes the efficiency of an in vitro splicing assay (12). Similarly, blocking the activity of cyclin L1, a cyclin partner of CDK11p110, inhibits the second step (cutting of the lariat-exon intermediate and ligation of adjacent exons) of pre-mRNA splicing in an in vitro assay (7).

A recently identified Cdc2-related kinase, CrkRS, is also implicated in the regulation of RNA splicing (16). CrkRS contains an arginine- and serine-rich (RS) domain, a characteristic found in the SR protein family of splicing factors. Furthermore, CrkRS localizes in nuclear speckles and CrkRS-immunoprecipitated complexes phosphorylate the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II and the splicing factor SF2/ASF in vitro, suggesting its roles in transcription and splicing. However, whether CrkRS has a cyclin partner is not clear, nor is it known to be involved in alternative splicing machinery.

In a previous study, we surveyed the expression profiles of protein kinases in cultured neurons and in early developing neural tissues by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR using primers corresponding to conserved amino acids in the kinase domain (18). Several PCR fragments whose sequences corresponded to novel kinases at that time were identified. One of the fragments contains sequences similar to the CDC2 kinase domain. In this study, we characterized this kinase and showed that it is a shorter isoform of CrkRS.

Based on coprecipitation experiments as well as colocalization studies, we demonstrated that both isoforms of CrkRS interact with cyclin L1 and cyclin L2 and renamed these isoforms CDK12L (the long isoform of CDK12) and CDK12S (the short isoform of CDK12). Furthermore, overexpression of CDK12 isoforms, cyclin L1, and cyclin L2 affects the splicing pattern of the E1a minigene, and perturbation of CDK12 expression changes the splicing pattern in a reverse manner. We also demonstrated that the effect of CDK12 on the E1a splicing pattern is inhibited by overexpression of SF2/ASF and SC35. These results provide initial evidence that CDK12 and its cyclin partners are involved in alternative RNA splicing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and reagents.

Pregnant and postnatal Sprague-Dawley rats were obtained from the animal facility of National Yang-Ming University. Handling of the animals was according to university guidelines and was approved by the National Yang-Ming University Animal Care and Use Committee. Superscript reverse transcriptase II and chemicals used in tissue culture were purchased from Gibco-BRL (Grand Island, NY). Expand high-fidelity Taq DNA polymerase, dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP, 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), and the protease inhibitor cocktail were obtained from Roche (Mannheim, Germany). RNase inhibitor (RNasin) and Taq DNA polymerase were purchased from Promega (Madison, WI). Hybond-N+ nylon membranes, mRNA purification kits, and Rediprime II kits were purchased from Amersham Pharmacia (Buckinghamshire, England). The primers used in PCR were synthesized by MDBioMed (Taipei, Republic of China). The Marathon kits were from Clontech (Palo Alto, CA). All other chemicals, unless otherwise specified, were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany).

cDNA cloning of CDK12S.

Total RNA was prepared as described previously (5). A fragment of rat CDK12S was obtained by degenerated RT-PCR from embryonic day 14.5 (E14.5) cortical neurons (18). To obtain 5′ and 3′ fragments of rat CDK12S, 5′ and 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) was performed using the Marathon kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. The 5′- and 3′-RACE products were cloned into pCR II (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for DNA sequencing.

Northern blotting analysis.

Polyadenylated mRNAs or total RNAs were separated on a 1% denaturing agarose gel and transferred to Hybond-N+ nylon membranes. The membranes were prehybridized at 65°C for 2 h in prehybridization solution (0.125 M Na3PO4 [pH 7], 0.25 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10% PEG-6000, 7% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 1% bovine serum albumin) and then hybridized with probes corresponding to nucleotide sequence 90 to 786 (probe 1) of the rat CDK12S (accession number NM_138916), 3814 to 4381 (probe 2) of the rat CDK12S or 3951 to 4268 (probe 3) of the rat CDK12L (accession number AY962568). After hybridization at 65°C for 20 h, membranes were washed three times in 0.5× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate at 65°C for 30 min before autoradiography. For normalization, blots were stripped and reprobed with a cyclophilin probe.

Vector construction.

To construct pCDK12S, the CDK12S coding region was amplified from E14.5 rat brain cDNA by RT-PCR and cloned into pHA (a gift from C.-J. Huang, Academia Sinica, Taipei, Republic of China). To construct the pEGFP-Myc expression vector, the enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) coding region was amplified from vector pCRG and ligated into vector pEF (Invitrogen). CDK12S and truncated CDK12 fragments were amplified by PCR using pCDK12S as a template and cloned into pEGFP-Myc, such that the vectors were able to express EGFP-fused CDK12S and truncated CDK12 proteins tagged with Myc and His tags. Human CDK12S and CDK12L were amplified from cDNA of HeLa cells and cloned into pEF. The resulting vectors (phCDK12S and phCDK12L) express untagged human CDK12S and CDK12L proteins.

To construct pcyclin L1α-Flag, pcyclin L1β-Flag, and pcyclin L2α-Flag expression vectors, the coding regions were amplified from E14.5 rat cDNA using primer sets containing Flag and the stop codon sequence and cloned into pEF. Cyclin L1α-Flag and cyclin L1β-Flag were also cloned into pEGFP as pEGFP-cyclin L1α-Flag and pEGFP-cyclin L1β-Flag.

The SR protein expression vectors, including pSF2/ASF, pSC35, pSRp40, pSRp55, and pSRp75, were kindly provided by W.-Y. Tarn. These vectors were derived from pCEP4 and express hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged SR proteins. RNA recognition motifs 1 and 2 of SF2/ASF, the RS domain of SF2/ASF, the RNA recognition motif of SC35, and the RS domain of SC35 were amplified by PCR and then cloned into pCEP4 for truncated HA-tagged SR proteins. For RNA interference experiments, synthesized double-stranded DNA fragments corresponding to 1488 to 1513 (pCDK12si1) and 2809 to 2834 (pCDK12si2) of mouse CDK12 (accession number NM_138916) were cloned into vector pmU6 (32). For antigen expression in Escherichia coli, cDNA fragments were cloned into pET29a (Clontech). All constructs were verified by sequencing.

Cell cultures and transfection.

HEK293T cells were cultured at 37°C in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum in a 5% CO2 incubator. P19 cells were cultured in α minimal essential medium supplemented with 2.5% fetal bovine serum and 7.5% newborn calf serum. To introduce various constructs into HEK293T and P19 cells, calcium phosphate transfection cocktails (5 mg/ml HEPES, 5 mg/ml NaCl, 0.37 mg/ml KCl, 1 mg/ml d-glucose, 0.1 mg/ml Na2HPO4, pH 7.05, 125 μM calcium chloride, and 20 μg expression vector) were added to cells grown at 70% confluence in 10-cm culture dishes. Alternatively, cells were transfected using FuGENE6 (Roche) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The medium was changed 18 h after transfection. Cells were harvested 24 to 48 h after transfection. For the small interfering RNA experiments, pBiCS2-Puro/GFP (a gift from D. L. Turner, University of Michigan) was cotransfected with other plasmids into P19 cells. The P19 cells were then selected using 5 μg/ml of puromycin 18 h after transfection. Cells were harvested 48 h after transfection.

Antibodies.

DNA fragments corresponding to amino acid residues 1040 to 1212 of rat CDK12 (peptide 1) and amino acid residues 1297 to 1402 of CDK12L (peptide 2) were amplified and cloned into pET29a. The recombinant proteins produced by the two bacterial strains were purified by a Ni2+ column. Peptide 1 was injected into rabbit spleen to produce rabbit antiserum. The resulting antiserum (rαCDK12) was used at 1:2,000 dilution for immunofluorescence staining. Peptide 1 and peptide 2 were separately injected into BALB/c mice seven times before collection of the two antisera. The mouse antisera (mαCDK12 and mαCDK12L) were diluted at 1:2,000 for Western blots. Mouse anti-Flag M2 monoclonal antibody was from Kodak (New Haven, CT). Mouse anti-Myc monoclonal antibody (9E10) and mouse anti-β-tubulin antibody (E7) were obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (University of Iowa, IA), and rabbit anti-Myc antibody was from Bethyl (Montgomery, TX). Rhodamine-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G was purchased from Caltag Laboratories (Burlingame, CA). Other secondary antisera were from Cappel (Aurora, Ohio).

Protein extraction, immunoprecipitation, and Western blotting analysis.

Rat tissues were homogenized in Laemmli lysis buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 2% NP-40, 0.2% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 50 mM NaF, and the protease inhibitor cocktail) for Western analysis. Transfected cells were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline and dissolved in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.8, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% Triton X-100, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and protease inhibitor cocktail). The cell lysates were cleared by centrifuging at 13,000 × g force for 10 min, and supernatants were used for Western blotting analysis or immunoprecipitation. The protein concentration was determined using a BCA kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Immunoprecipitation was performed with 300 μg of protein extract and 2 μl of undiluted primary antibodies in a reaction volume of 500 μl at 4°C on a rotator for at least 12 h. The immune complex was absorbed onto 15 μl protein A/G beads (Calbiochem, Cambridge, MA) at 4°C on a rotator for 30 min. Samples were spun down by low-speed centrifugation and washed 5 times with RIPA lysis buffer. For Western blotting analysis, equal amounts of either tissue or cell lysate were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The membrane was blocked with 5% skimmed milk and probed with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. After the membrane was washed and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1 h, it was developed with an ECL kit (Amersham Pharmacia). Membranes were then stripped and reprobed with an anti-β-tubulin antibody.

In vivo splicing assay.

The pCEP4-E1a minigene vector was kindly provided by W.-Y. Tarn. HEK293T or P19 cells cultured in six-well plates were cotransfected with 0.4 μg of pCEP4-E1a and different amounts of Myc-tagged CDK12 isoform plasmids, Flag-tagged cyclin L1α plasmids, and/or SR plasmids. The amounts of plasmid were equalized in each well by the addition of the backbone vector (pEGFP, pEF, or pCEP4). Total RNAs from the transfected cells were extracted 32 to 48 h after transfection by the RNeasy minikit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

RT-PCR was then performed to amplify the various transcripts of E1a minigene. To detect the RT-PCR products, standard Southern blotting was performed. The 9S RT-PCR fragment of E1a minigene was used as the probe. Intensities of 13S, 12S, and 9S in the autoradiography were measured by the ImageQuant (version 1.1, Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA) or the Scion image (Beta 4.0.2, PC format of NIH Image by Wayne Rasband of National Institutes of Health) program. The percentage of each isoform relative to the total amount of three isoforms in each sample was calculated and further normalized to the control. Each experiment was performed at least three times. Statistical analysis was performed by paired t test, and the P value for statistical significance was set at 0.05.

Immunofluorescence microscopy.

Transfected HEK293T cells grown on coverslips were rinsed once with phosphate-buffered saline and then fixed in ice-cold methanol for 10 min. The samples were stained with appropriate primary antibodies and then with rhodamine-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antiserum or rhodamine-conjugated goat anti-mouse antiserum. The cells were finally stained with DAPI (1 μg/ml) for 10 min. The coverslips were examined by a fluorescence microscope (Eclipse E800M, Nikon) or a confocal microscope (TCS NT, Leica).

RESULTS

Cloning and sequence analysis of CDK12S.

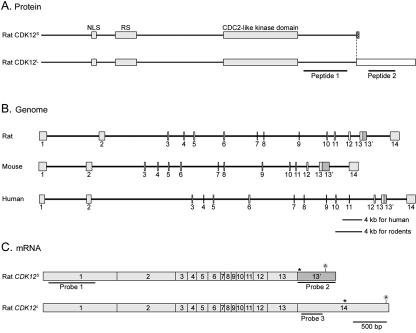

In a previous study, the expression profile of various protein kinases in rat cortical neurons was analyzed using degenerate RT-PCR and a nucleotide sequence identified as a novel CDC2-like kinase was isolated (18). Using RACE, we obtained a contiguous nucleotide sequence of 4,381 bp encoding an open reading frame of 1,258 amino acids. A polyadenylation signal was found at bp 4231 (Fig. 1C). Functional domains present in the deduced amino acid sequences were predicted by MotifScan search (http://hits.isb-sib.ch/cgi-bin/PFSCAN?) and included a bipartite nuclear localization signal, an RS domain, and a CDC2-like serine/threonine kinase domain (Fig. 1A). According to the characteristics of the sequence and the following data, we named the protein the short form of cyclin-dependent kinase 12 (CDK12S, accession number NM_138916). The sequences of the human and mouse CDK12S were then acquired by database comparison and were confirmed by RT-PCR and DNA sequencing. The deduced protein sequences of CDK12S are highly conserved among these species, with 90.7% identity between human and mouse, 91.8% identity between human and rat, and 96.5% identity between mouse and rat.

FIG. 1.

Protein, mRNA, and genomic structures of CDK12S and CDK12L. (A) Protein domains of CDK12S and CDK12L. The amino acid sequences of rat CDK12S and CDK12L were analyzed by the MotifScan program. CDK12S and CDK12L share 1,249 amino acids of sequence. They contain a bipartite nuclear localization signal (NLS), an arginine- and serine-rich motif (RS), and a CDC2-like kinase domain (gray boxes). CDK12S and CDK12L display 9 (hatched box) and 235 (blank box) distinct amino acid residues, respectively, at their carboxyl termini. Peptides 1 and 2 were used to generate antisera. (B) Genomic organization of CDK12. The exons were identified by comparing the cDNA sequences with the genomic sequences. The genomic structure of CDK12 contains 14 exons and is conserved between human, mouse, and rat. (C) mRNAs of CDK12S and CDK12L. The CDK12S and CDK12L transcripts share exons 1 to 13, and the CDK12S transcript reads through exon 13′, while the CDK12L transcript splices exon 13 directly to exon 14. The probes used in Northern analysis are underlined. Stop codons are labeled with asterisks. The position of the polyadenylation signal is also indicated.

A search of the nonredundant sequence database revealed that the cDNA sequences of the human Crkrs (NM_016507) and human CDK12S genes are identical at their 5′ ends (16). This suggests that they are alternatively spliced isoforms of the same gene. To confirm that the alternative splicing event is conserved, we cloned rat Crkrs cDNA, which encodes a protein of 1,484 amino acids, from E14.5 brain by RT-PCR. Alignment of the rat CDK12S and Crkrs cDNA sequences and comparison of these two sequences to rat genomic sequences indicates that CDK12S and Crkrs cDNAs are transcripts of the same gene, CDK12, and differ at the 3′ end (Fig. 1B and C).

There are 14 exons in the CDK12 gene. The CDK12S transcript skips the 5′ splice site at the end of exon 13 and contains exon 13′. As there is an in-frame stop codon in exon 13′, this results in a shortened open reading frame for CDK12S. In contrast, crkrs transcript splices out exon 13′ and connects exon 13 and 14, resulting in a longer open reading frame. For clarity, we renamed CrkRS CDK12L. Thus, the rat CDK12S and rat CDK12L proteins share the same 1,249 amino acids of the amino termini, but have an additional 9 and 235 distinct amino acid residues, respectively, at the carboxyl termini. An identical exon organization for the CDK12 gene is observed in the human and rodent genomes, albeit with different lengths of introns in the three species (Fig. 1B). The CDK12 gene is located on human chromosome 17q12 (AC009283) and on mouse chromosome 11 (AL591205). The closest homologous protein to human CDK12 is human CDC2L5 (22), which also contains a CDC2-like protein kinase domain and an RS domain.

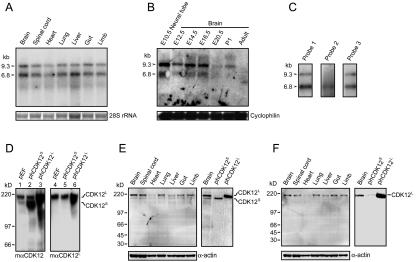

Expression analyses of rat CDK12.

Previously, Ko et al. detected CDK12 expression by Northern blotting using adult human tissues. Its expression in embryonic tissues was not analyzed. Moreover, the sizes of CDK12L and CDK12S transcripts were not determined. Thus, the expression of rat CDK12L and CDK12S transcripts in various tissues during embryonic development was analyzed using a probe (probe 1) that recognizes both transcripts. When total RNAs derived from E14.5 tissues were analyzed, two transcripts of CDK12 with sizes of 9.3 and 6.8 kb were detected (Fig. 2A). The CDK12 mRNAs were ubiquitously expressed in E14.5 tissues, including brain, spinal cord, heart, lung, liver, gut, and limb (Fig. 2A). We also examined the temporal expression pattern of CDK12 during the development of the nervous system. The CDK12 mRNAs were expressed in E10.5 neural tube, which was the earliest time point examined (Fig. 2B). The levels of CDK12 expression in rat brain are more abundant in the embryonic stages, gradually decrease as development proceeds, and became barely detectable at the adult stage (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Expression of CDK12 in embryonic rat tissues. (A) We used 5 μg of total RNA from various E14.5 rat tissues analyzed by Northern blotting using probe 1 depicted in Fig. 1C. Two major transcripts, 6.8 kb and 9.3 kb (arrowheads), were detected. Ethidium bromide staining of 28S rRNA was used as the loading control. (B) We used 30 μg of total RNA derived from E10.5 neural tube and brain at various developmental stages analyzed by Northern blotting. The membrane was stripped and reprobed with cyclophilin for the loading control. (C) Polyadenylated mRNA from E14.5 rat brain analyzed by Northern blotting using probe 1, probe 2, or probe 3. Probe 1 and probe 3 detected two transcripts, while probe 2 detected only the 6.8-kb transcript. (D) We used 20 μg of cell extracts of HEK293T transfected with control vector (pEF), phCDK12S and phCDK12L to examine the specificity of the mαCDK12 and the mαCDK12L antisera. The mαCDK12 antiserum recognizes both CDK12S and CDK12L, and the mαCDK12L antiserum recognizes only CDK12L. (E) Western analysis of 15 μg of E14.5 rat tissue extracts performed using mαCDK12 (left panel). The sizes of CDK12S and CDK12L detected in the E14.5 brain by the mαCDK12 antiserum are the same as those detected in 4 μg of CDK12S- or CDK12L-overexpressed HEK293T cell lysates (right panel). (F) Western analysis of 15 μg of E14.5 rat tissue extracts performed using mαCDK12L (left panel). The size of CDK12L detected in the E14.5 brain by the mαCDK12L antiserum is the same as that detected in 4 μg of CDK12L-overexpressed HEK293T cell lysates (right panel). Membranes were reprobed with the anti-α-actin antibody as the loading control.

To distinguish which transcripts correspond to CDK12S and CDK12L mRNAs in Northern blots, we designed probe 2 and probe 3, which specifically hybridize to the CDK12S and CDK12L mRNAs, respectively (Fig. 1C). In the Northern blots using CDK12S-specific probe 2, only the 6.8-kb band could be observed (Fig. 2C). Surprisingly, CDK12L-specific probe 3 could hybridize both the 9.3-kb and 6.8-kb bands, a pattern identical to that observed by probe 1 (Fig. 2C). The data indicate that two transcripts, with sizes of 9.3 and 6.8 kb, encode CDK12L; and a transcript with a size of 6.8 kb encodes CDK12S.

To verify that CDK12S and CDK12L transcripts can be translated to proteins and to examine endogenous protein expression of CDK12 in rat embryonic tissues by Western blotting, rabbit and mouse antisera (rαCDK12 and mαCDK12) were raised against peptide sequences 1040 to 1212 of rat CDK12 (peptide 1 in Fig. 1A) such that the antisera recognize both CDK12S and CDK12L. Mouse antisera (mαCDK12L) against amino acids 1297 to 1402 (peptide 2 in Fig. 1A) were also generated to detect only CDK12L. The specificity of the antibodies was determined by Western blotting using lysates of HEK293T cells transfected with a control vector (pEF), phCDK12S or phCDK12L. The latter two vectors were able to express human CDK12S and CDK12L protein, respectively.

In cells transfected with pEF, both mαCDK12 and mαCDK12L identified a 200-kDa band, suggesting that this band corresponds to CDK12L (Fig. 2D, lanes 1 and 4). mαCDK12, but not mαCDK12L, bound an additional 180-kDa band, suggesting that this band corresponds to CDK12S (Fig. 2D, lane 1). The data also indicated that HEK293T cells express CDK12S and CDK12L endogenously. The specificity of antibodies was further validated when CDK12S- or CDK12L-overexpressing HEK293T cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting (Fig. 2D). The sizes of CDK12S and CDK12L are larger than those predicted (140.0 kDa for CDK12S and 163.9 kDa for CDK12L), possibly due to posttranslational modification such as phosphorylation (16).

We then used these two antibodies to analyze the expression pattern of CDK12 in E14.5 rat tissues (Fig. 2E and F). Both CDK12S and CDK12L proteins were detected in E14.5 brain, spinal cord, heart, lung, liver, gut, and limb. The sizes of these two bands are identical to those found in HEK293T cells.

Interaction between CDK12, and cyclins L1 and L2.

It is possible that activation of CDK12 requires a cyclin. Examination of the cellular localization of known cyclins points to members of cyclin class L, cyclin L1 and cyclin L2, as good candidates for the cyclin partner of CDK12, as they contain an RS domain and are located in the nuclear speckles (6, 7, 31). To test this hypothesis, we determined whether CDK12 interacts with the cyclin L members.

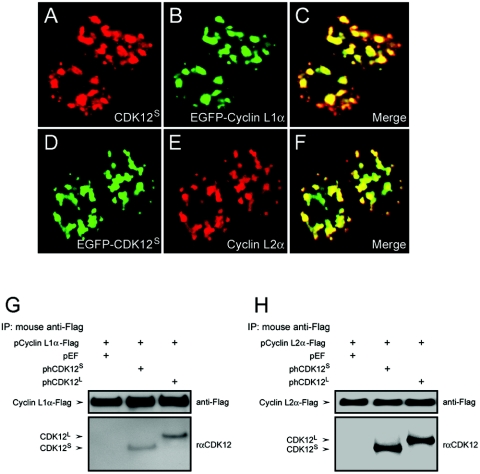

CDK12S and EGFP-tagged cyclin L1α (the longest isoform of cyclin L1) were overexpressed in HEK293T cells. The subcellular localization of CDK12S, recognized by rαCDK12, is in nuclear speckles and appears similar to the subcellular pattern of CDK12L reported previously (Fig. 3A) (16). As expected from previous studies (1, 7), EGFP-tagged cyclin L1α is located in the nuclear speckles (Fig. 3B) and is colocalized with CDK12S (Fig. 3C). CDK12S and cyclin L2α are also colocalized in nuclear speckles when overexpressed together in HEK293T cells (Fig. 2D to F).

FIG. 3.

Interaction between CDK12 and cyclin L1 and cyclin L2. (A to C) HEK293T cells transfected with pCDK12S-Myc and pEGFP-cyclin L1α-Flag were stained with the rαCDK12 antiserum (A) and examined for EGFP fluorescence (B). The merged photograph shows that CDK12S colocalizes with cyclin L1α in nuclear speckles (C). (D to F) HEK293T cells transfected with pEGFP-CDK12S and pcyclin L2α-Flag were examined for EGFP fluorescence (D) and stained with anti-Flag antibody (E). The merged photograph shows that CDK12S colocalizes with cyclin L2α in nuclear speckles (F). (G and H) Lysates of HEK293T cells transfected with the vectors indicated above the panels were immunoprecipitated with the anti-Flag antibody. The immunoprecipitates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with the anti-Flag antibody or the rαCDK12 antiserum. The expected positions of cyclin L1α, cyclin L2α, CDK12L and CDK12S are shown by arrows.

To demonstrate the possibility that CDK12 can associate with cyclin L1 and cyclin L2, immunoprecipitation experiments were performed. Cell lysates containing overexpressed CDK12S or CDK12L and Flag-tagged cyclin L1α or Flag-tagged cyclin L2α were immunoprecipitated by an anti-Flag antibody. The immune complex was then subjected to Western blotting. Both CDK12S and CDK12L were coimmunoprecipitated with cyclin L1α or L2α (Fig. 3G and H). Similarly, when cell lysates containing overexpressed Myc-tagged CDK12S and Flag-tagged cyclin L1α were immunoprecipitated by an anti-Myc antibody, it was shown that cyclin L1α was coimmunoprecipitated with CDK12S (Fig. 4B, lane 2).

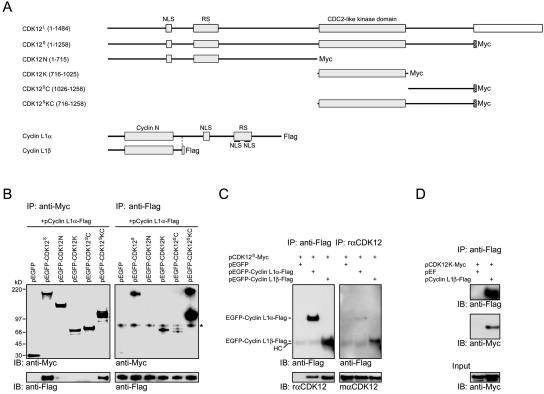

FIG. 4.

Mapping of interaction domains between CDK12 and cyclin L1. (A) Schematic structures of CDK12L, Myc-tagged CDK12S, various Myc-tagged CDK12 truncated constructs, Flag-tagged cyclin L1α, and Flag-tagged cyclin L1β. (B) Lysates of HEK293T cells transfected with various CDK12 truncated constructs and pcyclin L1α-Flag were immunoprecipitated with the anti-Myc antibody. The immunoprecipitates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with the anti-Flag antibody or the rabbit anti-Myc antiserum (left panels). The same lysates were also immunoprecipitated with the anti-Flag antibody. The immunoprecipitates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with the anti-Flag antibody or the rabbit anti-Myc antiserum (right panels). A nonspecific band was recognized by the rabbit anti-Myc antiserum (asterisk). (C) Lysates of HEK293T cells transfected with the plasmids listed above the panel and immunoprecipitated with the anti-Flag antibody. The resulting proteins were then immunoblotted using the rabbit anti-Flag antiserum or the rαCDK12 antiserum (left panels). The same lysates were immunoprecipitated with the rαCDK12 antiserum. The resulting proteins were then immunoblotted using the mαCDK12 antiserum or the anti-Flag antibody (right panels). A faint band corresponding to the heavy chain (HC) of antibodies used in the immunoprecipitation was detected by the secondary antibodies. (D) Lysates of HEK293T cell transfected with pCDK12K-Myc and pEF or pcyclin L1β-Flag were immunoprecipitated with the anti-Flag antibody. The resulting proteins were then immunoblotted using the anti-Flag antibody or the rabbit anti-Myc antiserum.

To study further the interaction between CDK12 and cyclin L1, we next mapped the domains involved in the interaction. Since CDK12S is sufficient to bind cyclin L1α and the amino acid sequence of CDK12S is included in CDK12L (except the last 9 amino acids), we used CDK12S as the starting template to study the interaction between CDK12 and cyclin L1. The Myc-tagged CDK12S or Myc-tagged truncated proteins (Fig. 4A) were coexpressed with Flag-tagged cyclin L1α in HEK293T cells. Immunoprecipitation with the anti-Flag antibody and Western blotting were then performed. The results showed that cyclin L1α protein was coprecipitated with CDK12S and the truncated CDK12 protein containing the kinase domain and the carboxyl-terminal domain (CDK12SKC, Fig. 4B, left panel).

In the reverse immunoprecipitation experiment, CDK12S and the kinase domain (CDK12K), carboxyl terminus (CDK12SC) or CDK12SKC were coprecipitated with cyclin L1α protein by the anti-Flag antibody (Fig. 4B, right panel). The cause for the discrepancy observed between these two immunoprecipitation experiments is unclear. One possibility is that binding of the anti-Myc antibody to CDK12K and CDK12SC during immunoprecipitation may generate steric hindrance that inhibits interaction between these proteins and cyclin L1α. Together, these results suggest that the kinase domain and carboxyl-terminal domain of CDK12S interact with cyclin L1α. In a control experiment, the anti-Flag antibody was unable to pull down CDK12S or truncated proteins using lysates of cells transfected with the CDK12 constructs but without pcyclin L1α-Flag (data not shown).

As many cyclins interact with CDK through the cyclin domain, we cloned a naturally occurring cyclin L1 isoform, cyclin L1β, which contains the cyclin domain but no carboxyl-terminal RS domain (Fig. 4A), and examined its interaction with CDK12 by immunoprecipitation. The results showed that cyclin L1β can interact with CDK12S (Fig. 4C). The kinase domain of CDK12 can also interact with cyclin L1β in the immunoprecipitation experiment (Fig. 4D).

CDK12 and cyclin L1 are regulators of alternative splicing.

It was reported that human CDK12L immune complex contains a kinase activity that phosphorylates SF2/ASF in vitro (16). We also found that immunoprecipitated rat CDK12S can phosphorylate SF2/ASF, although CDK12S does not directly phosphorylate SF2/ASF (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). As SF2/ASF is a member of the SR proteins, which are involved in the regulation of constitutive splicing as well as alternative splicing (9), we tested whether CDK12 and cyclin L1 change splicing site selection of an E1a minigene in HEK293T cells.

The pre-mRNA of the E1a minigene can be processed into five mRNAs. Three major forms, 13S, 12S, and 9S, derive from selection of one of three 5′ splice sites, and two minor forms, 11S and 10S, involve additional splicing using an upstream 3′ splice site (Fig. 5A). We transfected the E1a minigene together with pCDK12S or pCDK12L and then quantified the intensity ratios of the 13S, 12S, and 9S products after RT-PCR and Southern blotting. We normalized the percentages of the three major bands to those in the control experiments, so that changes in the splicing patterns are easily visualized.

FIG. 5.

Regulation of alternative splicing by CDK12 and cyclin L1. (A) A schematic diagram illustrating the splicing pattern of the E1a reporter gene. The alternative 5′ splice sites and splicing events that generate 13S, 12S, and 9S mRNAs are indicated above the diagram. The locations of the primers used for PCR analysis are marked by arrowheads. (B) HEK293T cells were transfected with 0.4 μg of pCEP4-E1a and 1.6 μg of phCDK12L or phCDK12S. The splicing assays were then performed as described under Materials and Methods. The upper panel shows a representative autoradiograph of the results. The positions of the 13S, 12S, 10S, and 9S transcripts are indicated on the left. The mean values and standard deviations from three independent experiments are shown in the lower panel. * indicates P < 0.05 in comparison to the control by paired t test. (C) HEK293T cells were transfected with 0.4 μg of pCEP4-E1a and the indicated amounts of pCDK12S-Myc. The upper panel shows a representative autoradiograph result. The mean values and standard deviations from three independent experiments are shown in the lower panel. * indicates P < 0.05 in comparison to the control by paired t test. (D) Splicing assays of HEK293T cells transfected with pCEP4-E1a (0.4 μg) and the indicated amounts of pcyclin L1α-Flag were performed. The upper panel shows a representative autoradiograph result. The mean values and standard deviations from three independent experiments are shown in the lower panel. * indicates P < 0.05 in comparison to the control by paired t test. (E) Splicing assays of HEK293T cells transfected with 0.4 μg of pCEP4-E1a and 2.8 μg of pCDK12S-Myc or pCDK12L-Myc and/or 0.8 μg of pcyclin L1β-Flag were performed. The upper panel shows a representative autoradiograph result. The mean values and standard deviations from four independent experiments are shown in the lower panel. * indicates P < 0.05 in comparison to the control and # indicates P < 0.05 between the pairs marked by connecting lines.

In HEK293T cells, both CDK12S and CDK12L decreased the 13S transcript and increased the 9S transcript (Fig. 5B). Moreover, this effect of CDK12 on E1a splicing pattern is dosage dependent (Fig. 5C). Similar dosage-dependent increases of the 9S transcript and decrease of the 12S and 13S transcripts were also observed when cyclin L1α and cyclin L2α were transfected into HEK293T cells (Fig. 5D; see Fig. S2B in the supplemental material). Changes of the splicing pattern of the E1a minigene were also observed when CDK12S and cyclin L1α were overexpressed in P19 cells (Fig. 6C, lanes 1 and 2). P19 cells are a mouse embryonic carcinoma cell line (8).

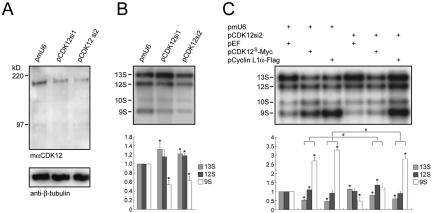

FIG. 6.

Changes in the alternative splicing pattern in cells with decreased expression of CDK12. (A and B) Proteins and RNAs of P19 cells transfected with 0.4 μg of pCEP4-E1a and 1.2 μg of pmU6, pCDK12si1, and pCDK12si2 were prepared. Proteins were subjected to Western analysis using the mαCDK12L antiserum (A). The membrane was reprobed with the anti-β-tubulin antibody. RNAs were subjected to splicing assays (B). The upper panel shows a representative autoradiograph result. Quantitative results derived from three independent experiments are shown in the lower panel. Standard deviations are indicated. * indicates P < 0.05 in comparison to the control by paired t test. (C) Splicing assays of P19 cells transfected with 0.4 μg of pCEP4-E1a and 0.6 μg of the plasmid indicated above each lane. The upper panel shows a representative autoradiograph result. The mean values and standard deviations from three independent experiments are shown in the lower panel. * indicates P < 0.05 in comparison to the control (lane 1) and # indicates P < 0.05 between the pairs marked by connecting lines.

As cyclin L1β, which contains mainly the cyclin domain, had lower activity in the E1a splicing assay (see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material), we examined whether it could potentiate the effects of CDK12. There was no change in the splicing pattern when 0.8 μg of pcyclin L1β was transfected into HEK293T cells (Fig. 5E, lane 4). However, this dose of pcyclin L1β potentiated the effects induced by 2.8 μg of phCDK12S and phCDK12L (Fig. 5E, compare lanes 5 and 6 to lanes 2 and 3).

To further confirm that CDK12 proteins are involved in alternative splicing, we knocked down mouse CDK12 in P19 cells, in which the expression of endogenous CDK12 is higher than that in HEK293T cells (data not shown). Two small interfering RNA constructs, pCDK12si1 and pCDK12si2, were transfected into P19 cells. Both constructs decreased endogenous CDK12 proteins by at least 40% (Fig. 6A). When the E1a minigene splicing assay was performed in P19 cells, fewer of the 13S transcripts and more of the 9S transcripts were detected in the control conditions (Fig. 6B, lane 1) compared to the levels in HEK293T cells. When CDK12 was knocked down, there were increases in the 13S transcript and decreases in the 9S transcript levels (Fig. 6B, lanes 2 and 3), a pattern opposite what was observed for the CDK12-overexpressed experiments. The small interfering RNAs also completely blocked any effect on the alternative splicing pattern generated by overexpression of CDK12S (Fig. 6C, compare lane 5 to lane 2). Moreover, when the expression of endogenous CDK12 was suppressed, the effect of overexpressed cyclin L1α on alternative splicing was also partially inhibited (Fig. 6C, compare lane 6 to lane 3), suggesting that the effects of cyclin L1 on alternative splicing, at least in part, are mediated by CDK12.

Effect of CDK12 on E1a splicing pattern is compromised by overexpression of SF2/ASF and SC35.

Many SR splicing factors have been shown to increase the 13S and 12S transcripts and to decrease the 9S transcript, a pattern opposite what was observed in the case of CDK12 in the E1a splicing assay (26, 28, 33). We thus hypothesized that CDK12 may deplete the activities of SR proteins in the splicing machinery by indirect phosphorylation or sequestration of SR proteins and change the way in which the splicing machinery selects splice sites. If this hypothesis is correct, we reasoned that overexpression of SR proteins may counteract the effects of CDK12 on the E1a splicing pattern.

We examined this possibility by overexpressing five SR splicing factors, including SF2/ASF, SC35, SRp40, SRp55, and SRp75, with or without CDK12S in HEK293T cells for the E1a assay. In HEK293T cells, due to their already greater amounts of the 13S transcript, no further increase of the 13S transcript was observed by overexpression of SR proteins alone (Fig. 7A, lanes 3 to 6), except the minor increase caused by overexpression of SF2/ASF (Fig. 7A, lane 2). Among the five SR proteins tested, SF2/ASF partially inhibited and SC35 almost eliminated the effect of CDK12S in the E1a assay (Fig. 7A, compare lanes 8 and 9 to lane 7). The other three SR proteins had no influence on CDK12S activity. Some of the HEK293T cell lysates used for the splicing assay were used in Western analyses to detect the overexpressed proteins. The results showed that SR proteins were expressed as expected and ectopic expression of SR proteins did not affect synthesis of CDK12S proteins (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Moreover, no changes in the molecular weights of all the SR proteins tested were observed when SR proteins and CDK12S proteins were coexpressed.

FIG. 7.

Inhibition of CDK12 alternative splicing activity by SR proteins. (A and B) Splicing assays of HEK293T cells transfected with 0.4 μg of pCEP4-E1a and 1.8 μg of the plasmids listed above the panels were performed. The splicing assays were then performed as described under Materials and Methods. The upper panel shows a representative autoradiograph of the results. The positions of the 13S, 12S, 10S, and 9S transcripts are indicated on the right. The mean values and standard deviations from three independent experiments are shown in the lower panel. * indicates P < 0.05 in comparison to the control (lane 1) and # indicates P < 0.05 between the pairs marked by connecting lines by paired t test.

Previous reports had shown that the RNA recognition motifs (RRMs), but not the RS domain, mediate the effect of SF2/ASF in the E1a splicing assay (4, 30). We thus tested whether the RRMs of SF2/ASF are sufficient to block the effect of CDK12S in the E1a assay. As expected, the RRMs of SF2/ASF, but not the RS domain, changed the E1a splicing pattern (Fig. 7B, lanes 2 and 3) and eliminated the effect of CDK12S (Fig. 7B, compare lane 7 to lane 6). However, neither the RRM nor the RS domain of SC35 offset the effect of CDK12S, suggesting that both domains of SC35 were required to counteract CDK12S (Fig. 7B, lanes 9 and 10). Together, these data suggested that one of the mechanisms by which CDK12 regulates alternative splicing is mediated by blockage of the activities of SF2/ASF and SC35.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we describe the cloning of a shorter isoform of crkrs and demonstrate that both isoforms interact with cyclin L1, and we renamed them as isoforms of CDK12. Based on a comparison of genomic DNA sequences, these isoforms result from alternative splicing. Unlike canonical CDKs, CDK12S and CDK12L are proteins with high molecular weights and have an extended amino-terminal region that contains an RS domain. By Northern and Western analyses, both isoforms of CDK12 are ubiquitously expressed in embryonic tissues. A lower level of CDK12 proteins is detected in adult rat tissues (data not shown). In the present report, both CDK12S and CDK12L proteins are shown to associate with members of the cyclin L class and act similarly in the splicing assay. Further experiments are needed to reveal whether there are functional differences between the CDK12S and CDK12L proteins in terms of these activities.

Our results from the coprecipitation and colocalization experiments show that CDK12 associates with cyclin L1 and cyclin L2. We further demonstrate that this interaction occurs mainly between the kinase domain of CDK12 and the cyclin domain of cyclin L1, albeit the carboxyl-terminal region of CDK12S also interacts weakly with cyclin L1 (Fig. 4B). In the E1a minigene splicing assay, CDK12, cyclin L1α, and cyclin L2α increase formation of the 9S transcript at the expense of the 13S transcript in HEK293T cells. Furthermore, addition of a very small amount of the cyclin domain of cyclin L1 potentiates the effect of CDK12S on the change in alternative splicing, suggesting that these two proteins collaborate. Note that there is endogenous expression of CDK12 and cyclin L1α in HEK293T cells and P19 cells, which makes it difficult to display a strong synergistic effect between cyclin L1 and CDK12.

The cooperation between CDK12 and cyclin L1 is further suggested by the small interfering RNA experiments. Introduction of CDK12 small interfering RNAs into cultured cells not only partially decreases endogenous CDK12 expression, hence increasing the 13S transcript in the E1a minigene assay, but also eliminates the effect of overexpressed CDK12 in the splicing assay. Moreover, in the presence of CDK12 small interfering RNAs, the effects of overexpressed cyclin L1α are also partially blocked (Fig. 6C), which further substantiates the interaction between CDK12 and cyclin L1. The fact that blockage of the cyclin L1α effect by the CDK12 small interfering RNAs is incomplete is not unexpected, as cyclin L1α may associate with other CDKs, in addition to CDK12, to regulate RNA processing. At least one known CDK, CDK11p110, has been demonstrated to interact with cyclin L1α, and this protein is involved in constitutive splicing as measured by an in vitro assay (12). It is possible that CDK11p110 regulates alternative splicing in the same manner as CDK12, and by acting with CDK11p110 the overexpressed cyclin L1α protein may still be able to change the splicing pattern even in the absence of CDK12.

The protein sequence of human CDK12 is very similar to that of a recently identified kinase, CDC2L5 (22). There is 92% amino acid identity in the kinase domain and 52% identity overall between human CDK12L and human CDC2L5. Like CDK12, CDC2L5 contains an RS domain at the amino-terminal region. It has thus been suggested that these two genes belong to a new subfamily in the CDC2-like protein kinase family (22). In view of the structural similarity between CDK12 and CDC2L5, it is likely that CDC2L5 may interact with cyclin L1 or a related cyclin(s) and regulate RNA processing.

The observed effects of CDK12/cyclin L1 on the E1a minigene, with a decrease of the 13S transcript and a concurrent increase of the 9S transcript, are opposite those exerted by SR proteins (26, 28). Interestingly, we found that overexpression of SF2/ASF and SC35, but not SRp40, SRp55, and SRp75, offsets the effect of CDK12 on alternative splicing (Fig. 7A). The relationship between CDK12, SF2/ASF, and SC35 is currently unclear. There is no direct phosphorylation of SF2/ASF in vitro by CDK12 (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), and no molecular weight increase of SR proteins is observed when SR proteins are coexpressed with CDK12 (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Moreover, there was no increase of phosphorylated endogenous SR proteins detected by the 1H4 antibody, which recognizes phosphoserine in the RS domain, when CDK12 was overexpressed in cultured cells (data not shown). One possibility is that CDK12 affects splicing patterns by sequestering SR proteins by its interaction with SR proteins. It has been suggested that nuclear factors SAF-B and YT521-B bind and sequester SR proteins to affect splice site selection (11, 24). By saturating the CDK12 binding sites, overexpression of SF2/ASF and SC35 thus eliminates the CDK12 effect. CDK12 deletion constructs and mutations are needed to sort out whether sequestration of SR proteins by CDK12 is likely. As SF2/ASF and SC35 are essential for constitutive splicing and alternative splicing and are involved in maintaining genome stability (17), our results may also show another way to control the activities of these two splicing factors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Woan-Yuh Tarn, Chang-Jen Huang, and David L. Turner for providing reagents and Shu-Fen Tsai, Yui-Ing Yu and Shu-Huei Wang for assistance with the confocal microscopy. We thank Zi-Jay Shan, I-Jan Shan, and Hsin-I Yu for generating mαCDK12L antisera and Shu-Fen Lin for cloning mouse CDK12S. We are also grateful to Lung-Sen Kao, Chen-Kung Chou, and Woan-Yuh Tarn for critical reading of the manuscript and to other laboratory members for their help in manuscript preparation.

This work was supported by grants from the National Health Research Institute (NHRI-GT-EX89S732C), Yen Tjing Ling Medical Foundation, and the Program for Promoting Academic Excellence from Ministry of Education, ROC, to M.-J.F.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berke, J. D., V. Sgambato, P. P. Zhu, B. Lavoie, M. Vincent, M. Krause, and S. E. Hyman. 2001. Dopamine and glutamate induce distinct striatal splice forms of Ania-6, an RNA polymerase II-associated cyclin. Neuron 32:277-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black, D. L. 2000. Protein diversity from alternative splicing: a challenge for bioinformatics and post-genome biology. Cell 103:367-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brett, D., J. Hanke, G. Lehmann, S. Haase, S. Delbruck, S. Krueger, J. Reich, and P. Bork. 2000. EST comparison indicates 38% of human mRNAs contain possible alternative splice forms. FEBS Lett. 474:83-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caceres, J. F., T. Misteli, G. R. Screaton, D. L. Spector, and A. R. Krainer. 1997. Role of the modular domains of SR proteins in subnuclear localization and alternative splicing specificity. J. Cell Biol. 138:225-238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chomczynski, P., and N. Sacchi. 1987. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal. Biochem. 162:156-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Graaf, K., P. Hekerman, O. Spelten, A. Herrmann, L. C. Packman, K. Bussow, G. Muller-Newen, and W. Becker. 2004. Characterization of cyclin L2, a novel cyclin with an arginine/serine-rich domain: phosphorylation by DYRK1A and colocalization with splicing factors. J. Biol. Chem. 279:4612-4624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dickinson, L. A., A. J. Edgar, J. Ehley, and J. M. Gottesfeld. 2002. Cyclin L is an RS domain protein involved in pre-mRNA splicing. J. Biol. Chem. 277:25465-25473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edwards, M. K., and M. W. McBurney. 1983. The concentration of retinoic acid determines the differentiated cell types formed by a teratocarcinoma cell line. Dev. Biol. 98:187-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fu, X. D. 1995. The superfamily of arginine/serine-rich splicing factors. RNA 1:663-680. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garcia-Blanco, M. A., A. P. Baraniak, and E. L. Lasda. 2004. Alternative splicing in disease and therapy. Nat. Biotechnol. 22:535-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hartmann, A. M., O. Nayler, F. W. Schwaiger, A. Obermeier, and S. Stamm. 1999. The interaction and colocalization of Sam68 with the splicing-associated factor YT521-B in nuclear dots is regulated by the Src family kinase p59(fyn). Mol. Biol. Cell 10:3909-3926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu, D., A. Mayeda, J. H. Trembley, J. M. Lahti, and V. J. Kidd. 2003. CDK11 complexes promote pre-mRNA splicing. J. Biol. Chem. 278:8623-8629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium. 2004. Finishing the euchromatic sequence of the human genome. Nature 431:931-945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium. 2001. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature 409:860-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson, J. M., J. Castle, P. Garrett-Engele, Z. Kan, P. M. Loerch, C. D. Armour, R. Santos, E. E. Schadt, R. Stoughton, and D. D. Shoemaker. 2003. Genome-wide survey of human alternative pre-mRNA splicing with exon junction microarrays. Science 302:2141-2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ko, T. K., E. Kelly, and J. Pines. 2001. CrkRS: a novel conserved Cdc2-related protein kinase that colocalises with SC35 speckles. J. Cell Sci. 114:2591-2603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li, X., and J. L. Manley. 2005. Inactivation of the SR protein splicing factor ASF/SF2 results in genomic instability. Cell 122:365-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin, S. D., and M. J. Fann. 1998. Differential expression of protein kinases in cultured primary neurons derived from the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, and sympathetic ganglia. J. Biomed. Sci. 5:111-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loyer, P., J. H. Trembley, R. Katona, V. J. Kidd, and J. M. Lahti. 2005. Role of CDK/cyclin complexes in transcription and RNA splicing. Cell Signal. 17:1033-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loyer, P., J. H. Trembley, J. M. Lahti, and V. J. Kidd. 1998. The RNP protein, RNPS1, associates with specific isoforms of the p34cdc2-related PITSLRE protein kinase in vivo. J. Cell Sci. 111:1495-1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maniatis, T., and B. Tasic. 2002. Alternative pre-mRNA splicing and proteome expansion in metazoans. Nature 418:236-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marques, F., J. L. Moreau, G. Peaucellier, J. C. Lozano, P. Schatt, A. Picard, I. Callebaut, E. Perret, and A. M. Geneviere. 2000. A new subfamily of high molecular mass CDC2-related kinases with PITAI/VRE motifs. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 279:832-837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murray, A. W., and D. Marks. 2001. Can sequencing shed light on cell cycling? Nature 409:844-846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nayler, O., W. Stratling, J. P. Bourquin, I. Stagljar, L. Lindemann, H. Jasper, A. M. Hartmann, F. O. Fackelmayer, A. Ullrich, and S. Stamm. 1998. SAF-B protein couples transcription and pre-mRNA splicing to SAR/MAR elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 26:3542-3549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Philips, A. V., and T. A. Cooper. 2000. RNA processing and human disease. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 57:235-249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Screaton, G. R., J. F. Caceres, A. Mayeda, M. V. Bell, M. Plebanski, D. G. Jackson, J. I. Bell, and A. R. Krainer. 1995. Identification and characterization of three members of the human SR family of pre-mRNA splicing factors. EMBO J. 14:4336-4349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shin, C., and J. L. Manley. 2004. Cell signalling and the control of pre-mRNA splicing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 5:727-738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van der Houven van Oordt, W., K. Newton, G. R. Screaton, and J. F. Caceres. 2000. Role of SR protein modular domains in alternative splicing specificity in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:4822-4831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Venables, J. P. 2004. Aberrant and alternative splicing in cancer. Cancer Res. 64:7647-7654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang, J., and J. L. Manley. 1995. Overexpression of the SR proteins ASF/SF2 and SC35 influences alternative splicing in vivo in diverse ways. RNA 1:335-346. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang, L., N. Li, C. Wang, Y. Yu, L. Yuan, M. Zhang, and X. Cao. 2004. Cyclin L2, a novel RNA polymerase II-associated cyclin, is involved in pre-mRNA splicing and induces apoptosis of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 279:11639-11648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu, J. Y., S. L. DeRuiter, and D. L. Turner. 2002. RNA interference by expression of short-interfering RNAs and hairpin RNAs in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:6047-6052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang, W. J., and J. Y. Wu. 1996. Functional properties of p54, a novel SR protein active in constitutive and alternative splicing. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:5400-5408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.