Abstract

Objective: This case control survey compared health history and healthcare utilization of women with vulvodynia to a control group reporting absence of gynecologic pain.

Methods: Women with a clinically-assessed diagnosis of vulvodynia and asymptomatic controls were frequency matched on age and mailed a confidential survey that evaluated demographics, health history, use of the healthcare system, and history of vulvodynia. Participants were all current or former ambulatory patients within a university healthcare system.

Results: Of the 512 questionnaires mailed to valid addresses, 70% (n = 91) of cases and 72% (n = 275) of controls responded, with 77 cases and 208 controls meeting eligibility criteria. Cases reported a substantial negative impact on quality of life, with 42% feeling out of control of their life and 60% feeling out of control of their body as a consequence of vulvodynia. Forty-one percent indicated a severe impact on their sexual life. When co-morbidities were evaluated individually and adjusted for age, fibromyalgia (OR = 3.84, 95% CI 1.54-9.55) and irritable bowel syndrome (OR = 3.11, 95% CI 1.6-6.05) were significantly associated with vulvodynia. On a multivariate level, vulvodynia was correlated with a history of chronic yeast vaginitis and urinary tract infections.

Conclusions: This survey highlights the psychological distress associated with vulvodynia, and underscores the need for prospective studies to investigate the relationship between chronic bladder and vaginal infections as etiologies for this condition. As well, the association of vulvodynia with other co-morbid conditions such as fibromyalgia and irritable bowel syndrome needs to be further evaluated.

Introduction

Vulvodynia is a chronic vulvar pain condition of uncertain etiology1 that affects up to 16% of women in the general population.2 Although the literature provides insight into the physical, sexual, and psychological aspects of this condition, less attention has been given to the relationship between vulvodynia and other chronic medical conditions or to the impact of vulvodynia on the healthcare community. Individuals with vulvodynia are often reported to seek help from multiple clinicians in an attempt to establish a diagnosis for their condition and effective alleviation of their symptoms.3 Clinical profiles suggest that more than half of women with vulvodynia may suffer from additional chronic health conditions, such as repeated yeast infections, chronic fatigue syndrome and irritable bowel syndrome.4 However, the literature sheds little light on how these characteristics compare to women who seek care for other, general medical conditions.

Case control studies are a valuable means of identifying clinical predictors and comorbidities of a particular condition, such as vulvodynia. The present case control study aimed to compare health history and healthcare utilization habits of women diagnosed with vulvodynia to that of an asymptomatic control group within the context of a care-seeking population.

Methods

In this case control survey study, women with vulvodynia (cases) and women without vulvodynia or other type of chronic gynecologic pain (controls) completed a confidential survey that assessed demographics (e.g., age, race, marital status), health history (e.g., medical conditions, obstetric/gynecologic history), use of the healthcare system (e.g. number/ nature of doctor's visits, insurance status), quality of life (QOL), and, where applicable, history of vulvodynia (e.g., nature and duration of pain, exacerbating factors, perceived etiology, impact on daily activities). Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for the study from University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey (UMDNJ)-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School. Written consent of participants was waived with the acknowledgement that the return of a completed survey implied a subject's willingness to participate.

The questionnaire used was developed for the purpose of this study. Some of the questions, such as age, sex, and race, are used routinely in health questionnaires and have face validity. Others, such as medical history, may yield incomplete answers but nevertheless are widely used and provide a basis of comparison between cases and controls. As QOL scales are usually tailored to capture domains relevant to the health conditions under study, and as we found no previously published scales designed to assess the impact of vulvar pain on QOL, we used a modified Ladder of Life scale, a scale that has criterion validity for this area.

Subjects were selected from two pre-existing study populations. Eligible cases included up to 135 women who participated in vulvodynia research studies at UMDNJ and who had clinically-confirmed vulvodynia according to Friedrich's criteria (vulvar erythema in the absence of other pathology, pain upon vestibular touch/entry, and tenderness with localized pressure to the vestibule),5 with symptoms of at least six months duration. The control population was randomly selected from a group of 1,416 female patients of a multidisciplinary medical practice at UMDNJ who had responded to a 2001 women's health survey and who, at the time of that survey, had never experienced vulvodynia or any other form of chronic gynecologic pain. As part of the current study, controls were self-identified through a series of screening questions and to be considered a control, denied experiencing chronic vulvar symptoms lasting six months or longer. Cases and controls were frequency matched on six age categories (18–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, and 65–80 years); the control population was grouped according to birth date, and 450 names were randomly selected for participation proportionate to the age distribution of the case population.

Subjects were assigned a unique identification number, which was recorded on the survey and linked to names and addresses on a master file. A modified Dillman technique6, 7 was used to maximize the response rate. Specifically, an initial survey and letter explaining the study was sent to subjects at Week 1. Responses were monitored, and follow-up surveys and letters were mailed to non-responders at Weeks 3 and 5.

Controls who reported symptoms consistent with the 2000 International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD) definition of vulvodynia, specifically constant or intermittent burning, stinging, irritation or rawness of the genital area that may be exacerbated with tampon insertion, speculum insertion during a gynecologic exam, intercourse, or exercise were excluded from the final study population; as these women failed to indicate such symptoms in 2001, it is assumed that they developed after that time. Additionally, cases and controls with an active vulvovaginal or sexually transmitted infection and/or who were pregnant, as were cases whose vulvodynia was not confirmed by a UMDNJ clinician.

Case and control response rates were calculated, and descriptive statistics were generated for all variables assessed. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to whether the distribution of continuous variables (e.g., age, quality of life, and level of stress in life) was approximately normal. Mean values were compared using t-tests (for those showing a normal distribution) and differences among cases and controls for variables without a normal distribution were tested using the Wilcoxon rank test. Fisher's exact test was used to compare proportions in demongraphic variables whose subcategories had sparse responses (e.g., married, single, divorced/widowed). Univariate analysis was conducted, and with the number of cases and controls available, the study had approximate 80% power to detect relative risks of 3.64, 2.48, and 2.16 for variables with control group frequencies of 5%, 15%, and 30% respectively (using a two-sided two-sided alpha error of 5%).

Although cases and controls were frequency matched on age, a disproportionate number of older controls responded to the survey relative to younger controls. Additionally, mailing addresses were no longer valid for a number of younger controls, further reducing the available control population in the younger age groups. Consequently, the case population was significantly younger than the control population. Thus, Mantel Haenszel calculations and bivariate regression modeling were used to explore the effect of age on individual factors. Age-adjusted odds ratios were calculated and significant univariate associations determined. Statistical significance was established at p< 0.05. Logistic regression was used to model multiple variables simultaneously and identify significant predictors. The effects of age were studied in three categories [18–44 years (pre-menopausal), 45–54 years (peri-menopausal), and 55–80 years (post-menopausal)] in the regression models, with pre-menopausal women (age 18–44 years) as the reference group. SPSS 11.0 was used for data analysis.

Results

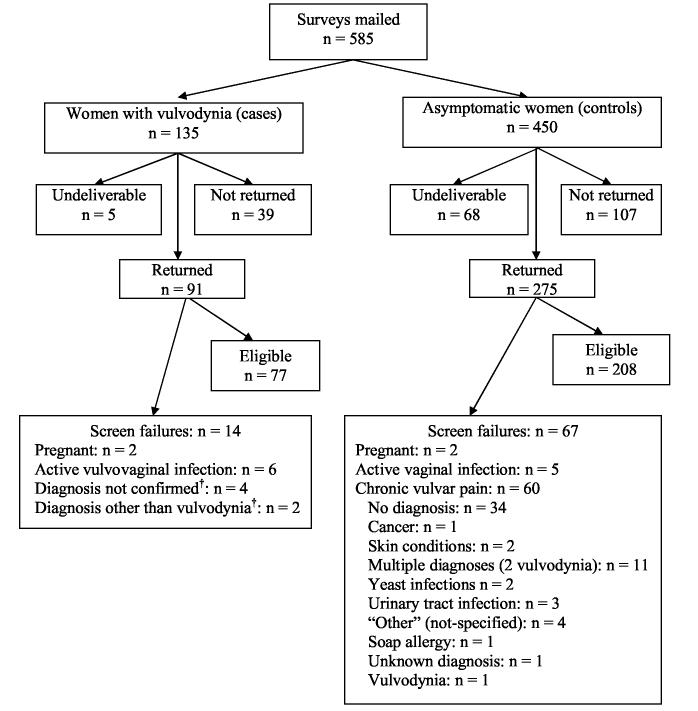

Questionnaires were mailed to 135 women with vulvodynia (cases) and to 450 women without vulvodynia or other chronic gynecologic pain (controls). Of these, 5 case surveys and 68 control surveys were returned as undeliverable. A 70% case response rate (n = 91 returned of 130 mailed) and a 72% response rate in the controls (n = 275 returned of 382 surveys mailed) was obtained. A total of 14 cases and 67 controls met exclusion criteria (Figure 1), leaving us with 77 cases and 208 controls for analysis.

Figure 1.

Mailing disposition of surveys sent to 585 women.*Surveys mailed to women who signed consent for UMDNJ clinical vulvodynia studies; review of non-responders indicated that a diagnosis of vulvodynia was not confirmed in three women, so they were excluded from the non-responder analysis.†A review of completed surveys from cases found that a UMDNJ clinician had not confirmed a diagnosis of vulvodynia in six women, and so they were excluded from the final analysis.

Sixty previously asymptomatic women (21.8%) included in the control mailing indicated that they now had chronic vulvar symptoms consistent with the ISSVD definition of vulvodynia. These 60 women were excluded from the final control population, but their responses to screening questions were reviewed for informational purposes. Although the majority (56%) had not received a diagnosis for their symptoms, three (1%) reported a diagnosis of vulvodynia since 2001. However, we had no clinical confirmation of this diagnosis. Additionally, as many of these 60 women were in their peri- or post-menopausal years, their unexplained vulvar symptoms may be the result of hormonal changes, such as atrophic vaginitis.

The final study population was primarily Caucasian and highly educated, with most participants having earned a college or graduate degree (Table 1). Cases were significantly younger than controls (p < 0.001) and more frequently reported being single, as compared to controls, which reported a higher divorce rate. There was a higher proportion of homemakers, students and retirees amongst controls, although this difference was not significant.

Table 1.

Demographics of 77 women with vulvodynia (cases) and 208 women without vulvodynia (controls).

| Cases (n = 77) | Controls (n = 208) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (± S. D.)* | 43.1 ± 13.7 | 51.1 ± 10.5 | ||

| Quality of Life (± S. D.)† | 7.0 ± 1.9 | 8.2 ± 1.4 | ||

| Stress in life (± S. D.)‡ | 5.9 ± 2.3 | 5.7 ± 2.4 | ||

| n | % | n | % | |

| Race | ||||

| White | 65 | 84.4 | 181 | 87 |

| Black | 2 | 2.6 | 13 | 6.2 |

| Asian | 3 | 3.9 | 5 | 2.4 |

| Native American or Alaskan | 2 | 2.6 | 1 | 0.5 |

| Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | ---- | ---- | 1 | 0.5 |

| Other | 3 | 3.9 | 7 | 3.4 |

| Missing | 2 | 2.6 | ---- | ---- |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 7 | 9.1 | 11 | 5.3 |

| Non-Hispanic | 68 | 88.3 | 191 | 91.8 |

| Missing | 2 | 2.6 | 6 | 2.9 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single§ | 18 | 23.4 | 10 | 4.8 |

| Married | 50 | 64.9 | 159 | 76.4 |

| Divorced/Widowed∥ | 6 | 7.8 | 38 | 18.3 |

| Other | 1 | 1.3 | 1 | 0.5 |

| Missing | 2 | 2.6 | ---- | ---- |

| Overall Health | ||||

| Excellent | 15 | 19.5 | 52 | 25.4 |

| Very good | 32 | 41.6 | 82 | 40.0 |

| Good | 28 | 36.4 | 60 | 29.3 |

| Fair | 2 | 2.6 | 10 | 4.9 |

| Poor | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 |

| Missing | 1 | 1.3 | 3 | 1.4 |

p < 0.001; n = 76 cases; n = 199 controls

p < 0.001; Average Quality of Life self-reported on a scale of 1 (worst) to 10 (best); n = 76 cases, 207 controls

Stress self-reported on a scale of 1 (least) to 10 (most); average value is shown; n = 76 cases, 207 controls

p < 0.001

p < 0.03

Although cases and controls reported similar levels of stress (Table 1), cases were more likely (p < 0.001) to report a worse overall quality of life, as measured on scale of 1 (worst) to 10 (best). Vulvodynia was significantly associated with worse overall quality of life (Table 1). Moreover, 42% felt out of control of their life, and 60% felt out their body specifically due to their chronic vulvar pain. Additionally, 90% of cases reported dyspareunia (painful intercourse), and 41% indicated that their condition had severely impacted their sexual life.

The majority (57%) of cases first experienced vulvodynia symptoms after age 30, although nearly one-fifth of the cases had their first symptoms under the age of 20 years (Table 3). “Burning” was the leading pain descriptor (88%), and slightly more than 25% of cases suffered constant vulvar pain. Approximately 1/3 of cases believed their vulvodynia was multifactorial in origin, with stress (25%), yeast infections (29%), unknown causes (38%), and “other factors” (41%) being most commonly cited. Sexual intercourse (75%), use of soaps (41%), tampons (36%), and laundry detergents (35%) were all noted to exacerbate symptoms. Seventy-five percent of cases had consulted three to nine doctors in their lifetime for their vulvar pain, and one-quarter had missed work at least once in the last year due to symptoms of vulvodynia.

Table 3.

Unadjusted and age-adjusted odds ratios comparing health history, obstetric and gynecologic history, healthcare utilization, and demographics for 77 women with vulvodynia and 208 women without vulvodynia.

| Characteristics | Cases (n = 77) | Controls (n = 208) | OR | 95% CI | Adjusted OR* | 95% CI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | missing | % | n | missing | % | ||||||

| High blood pressure | 8 | 2 | 10.7 | 55 | 1 | 26.6 | 0.33b | 0.15, 0.730 | 37† | 0.16, 0.88 | |

| Fibroids | 14 | 1 | 18.4 | 74 | 4 | 36.5 | 0.40b | 0.21, 0.760 | 46† | 0.23, 0.90 | |

| Chronic fatigue | 6 | --- | 7.8 | 5 | 6 | 3.0 | 3.33 | 0.99, 11.25 | 3.19 | 0.88, 11.42 | |

| Fibromyalgia | 12 | --- | 15.6 | 12 | 7 | 6.0 | 2.91b | 1.25, 6.79 | 3.84† | 1.54, 9.55 | |

| Depression | 22 | 2 | 29.3 | 46 | 5 | 22.8 | 1.42 | 0.78, 2.57 | 1.46 | 0.79, 2.7 | |

| Irritable Bowel Syndrome | 21 | 1 | 27.6 | 23 | 5 | 11.3 | 2.99b | 1.54, 5.81 | 3.11† | 1.6, 6.05 | |

| Sexually active in last 6 months | 57 | --- | 74.0 | 162 | --- | 77.9 | 0.81 | 0.44, 1.48 | 0.49† | 0.25, 0.97 | |

| History of PMS | 46 | 7 | 65.7 | 110 | 11 | 55.8 | 1.52 | 0.86, 2.68 | 1.14 | 0.63, 2.07 | |

| > 3 urinary tract infections/year | 20 | 6 | 28.2 | 16 | 4 | 7.8 | 4.61b | 2.23, 9.53 | 5.33† | 2.44, 11.62 | |

| > 3 yeast infections/year | 44 | 3 | 59.5 | 27 | 4 | 13.2 | 9.62b | 5.19, 17.8 | 9.89† | 5.23, 18.71 | |

| Used tampons regularly | 48 | 4 | 65.8 | 144 | 4 | 70.6 | 0.80 | 0.45, 1.41 | 0.80 | 0.45, 1.45 | |

| History of oral contraceptive use | 59 | --- | 76.6 | 153 | 2 | 74.3 | 1.14 | 0.62, 2.10 | 0.83 | 0.43, 1.6 | |

| OCP use > 5 years‡ | 26 | --- | 44.1 | 86 | --- | 56.2 | 0.61 | 0.34, 1.12 | 0.49† | 0.26, 0.95 | |

| History of pregnancy | 47 | 1 | 61.8 | 192 | 1 | 92.8 | 0.13b | 0.06, 0.26 | 0.14† | 0.07, 0.3 | |

| Ever used female hormones | 34 | --- | 44.2 | 86 | 2 | 41.7 | 1.10 | 0.65, 1.87 | 1.64 | 0.89, 3.02 | |

| Menopausal | 27 | 6 | 38.0 | 115 | 11 | 58.4 | 0.4b | 0.25, 0.76 | 0.56 | 0.22, 1.45 | |

| Hysterectomy | 6 | 2 | 8.0 | 42 | 2 | 20.4 | 0.34b | 0.14, 0.84 | 0.40 | 0.15, 1.1 | |

| Saw doctor > 1x/last year | 72 | --- | 93.5 | 180 | 1 | 87.0 | 2.16 | 0.8, 5.83 | 3.15† | 1.13, 8.78 | |

| See OB/GYN at least once/year | 70 | --- | 90.9 | 166 | 1 | 80.2 | 2.47 | 1.06, 5.77 | 2.17 | 0.91, 5.17 | |

| See specialist at least 1x/year | 54 | 1 | 74.1 | 111 | 3 | 54.1 | 2.08 | 1.18, 3.66 | 2.56† | 1.37, 4.55 | |

| Mental health care in last year | 21 | --- | 27.3 | 28 | 2 | 13.6 | 2.38b | 1.26, 4.52 | 2.49† | 1.29, 4.83 | |

| Employed§ | 61 | --- | 91.0 | 146 | --- | 83.9 | 1.95 | 0.77, 4.95 | 2.1 | 0.83, 5.31 | |

| In a committed relationship | 62 | 2 | 82.7 | 170 | 1 | 82.1 | 1.04 | 0.52, 2.08 | 0.79 | 0.38, 1.66 | |

OR = Odds Ratio; CI = Confidence Interval

Mantel-Hanszel age-adjusted odds ratio is presented

p < 0.05

Data based upon n = 59 cases and n = 153 controls who reported a history of oral contraceptive use

n = 7 cases and n= 25 controls excluded because of retirement; additional n = 3 cases and n = 8 controls excluded for missing information

Age-adjusted odds ratios demonstrated that controls were significantly more likely than cases to report a history of uterine fibroids, hypertension, or pregnancy. Cases, however, were not as sexually active in the six months prior to the survey than controls, and reported less use of oral contraceptives than controls (Table 4). Relative to controls, women with vulvodynia had three times the rate of co-morbid diagnoses of fibromyalgia (OR = 3.8; 95% CI 1.54-9.55) and irritable bowel syndrome (OR = 3.1; 95% CI 1.6-6.05). Of gynecologic conditions assessed, self-reported history of chronic yeast infections and chronic urinary tract infections had the strongest univariate associations with vulvodynia (OR = 5.3; 95% CI 2.44-11.62 and OR = 9.9; 95% CI 5.23-18.71 respectively); “chronic” was defined as three or more infections within a 12-month period.

Table 4.

Predictors of vulvodynia as determined through backward stepwise logistic regression with variables identified as significant (p < 0.05) in univariate analysis.*

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age 45–54 | 1.54 | 0.491, 4.805 | 0.460 |

| Age 55–80 | 0.83 | 0.278, 2.477 | 0.738 |

| Quality of life | 1.71 | 1.285, 2.275 | < 0.001 |

| Uterine fibroids | 0.14 | 0.042, 0.49 | 0.002 |

| Diagnosed with 3+ urinary tract infections in last year | 4.41 | 1.143, 17.01 | 0.031 |

| Diagnosed with 3+ yeast infections in last year | 6.11 | 2.473, 15.103 | < 0.001 |

| Ever pregnant | 0.18 | 0.049, 0.627 | 0.007 |

| Constant | 0.029 | ---- | 0.067 |

Age was forced into model, and all other variables (QOL, HTN, fibroids, fibromyalgia, IBS, intercourse in last 6 months, diagnosed with 3+ UTI/yr, diagnosed with 3+ yeast infections/yr, ever pregnant, seen mental health professional in last 6 months, see doctor > once per year, see specialist > once per year, took OCPs for > 5 years) were included as stepwise backwards regression; Hosmer Lemeshow Test Chi Square = 8.563, p = 0.381

With regard to utilization of the healthcare system, cases were about 50% more likely as controls to consult a specialist at least once in the last year. Similarly, cases were twice as likely as controls to have seen a mental health professional in the 12 months preceding the survey.

Logistic regression consistently yielded self-reported diagnoses of chronic yeast and chronic urinary tract infections as the strongest predictors of vulvodynia (OR = 4.4, p = 0.031; OR = 6.1, p = 0.000 respectively), with reduced quality of life also being significantly associated with vulvodynia (Table 5). Consistent with findings from the univariate analysis, vulvodynia had a reduced odds (p < 0.05) of being associated with pregnancy and uterine fibroids, even with age included in the model.

Healthcare utilization models indicated that vulvodynia was most strongly correlated with increasing age, and cases were less likely to have health insurance (Table 6); these findings were statistically significant (p < 0.05). Although women with vulvodynia also had an increased odds of seeing mental health providers, an OB/GYN, and medical specialists at least once a year and of consulting a healthcare provider an average of more than three times per year, these associations were not statistically significant.

Discussion

Prevalence estimates suggest that women suffering from vulvodynia comprise approximately 4% of the general population at a given point in time,2 with the representation as high as 15% in gynecologic clinic populations.8 With a final sample size of 77 clinically diagnosed vulvodynia cases, our study was on par with sample sizes of previous clinic-based studies.8-12 Since both cases and controls had previously participated in UMDNJ studies, and considering that all subjects had sought medical care at UMDNJ, effects of response bias were expected to balance out between the two groups.

Self-reported pain characteristics of the case population reflect the clinical profiles of vulvodynia patients reported in the literature,1 with vulvar burning the most commonly reported symptom in our population. The negative impact of vulvodynia on a woman's sexuality is well documented,4, 9, 13, 14 with just under half of cases in our study noting that this condition had an “extreme or disabling” impact on their sexual lives. Despite self-report of painful intercourse, approximately three-quarters of cases engaged in sexual activity within the six months preceding the survey, observations that are similar to other data that reported nearly two-thirds of women with vulvodynia who experienced dyspareunia had engaged in intercourse during the month prior to the survey.15 Such findings suggest that women with vulvodynia find alternates to “traditional” intercourse in an effort to maintain a fulfilling sexual life and emphasize the need for a thorough sexual history in women with this condition. Because of the high prevalence of dyspareunia in women with vulvodynia, the utility of counseling in non-coital types of sexual exchange should be explored.

Age-adjusted odds ratios indicated that fibromyalgia and irritable bowel syndrome were significantly associated with vulvodynia. The prevalence of these disorders amongst our overall study population reflects population-based estimates reported in the literature; within the context of cases and controls, the prevalence of fibromyalgia and irritable bowel syndrome in cases is in agreement with national estimates, while prevalence of these two conditions in controls is slightly higher than national estimates.16, 17 Such multifactorial chronic pain conditions of unknown etiology have been cited as being overrepresented in vulvodynia patients.4, 18, 19 Arguments have been made to classify such conditions as part of a chronic widespread pain syndrome20 and to also consider vulvodynia within the context of this model.4 These data suggest that women with vulvodynia should be questioned for symptoms of other chronic pain conditions. Furthermore, the potential relationship between these idiopathic, yet highly prevalent disorders is largely unexplored and may offer an avenue by which to examine the pathophysiology and management of vulvodynia.

Self-report of chronic yeast infections and urinary tract infections (each defined as three or more infections within 12 months) were the strongest predictors of vulvodynia in both univariate and multivariate models. Consistent with this finding, nearly 30% of cases believed that their vulvodynia was caused in part by yeast infections. As with any case control study, the potential for recall bias is acknowledged; cases may better remember past exposures, a particular concern in the instance of vulvodynia and vulvovaginal infection history. The literature also supports an association between vulvodynia and yeast infections,4, 5, 18, 21-24 with limited discussion on urinary tract infections,21 but the nature of these relationships is not well understood. Like our current study, previous research has relied upon self-report of infection history without laboratory confirmation of the diagnosis.

Surprisingly, although women with vulvodynia reported a significantly worse quality of life than controls, there were no significant differences in self-reported stress ratings or history of depression. Although vulvodynia is traditionally correlated with high levels of stress and depression,4, 5, 9, 10, 25, 26 several recent studies have indicated otherwise.9, 26 We also suggest that our findings may reflect study location. Participants, both cases and controls were recruited from an academic medical center in New Jersey, an area characterized by high rates of depression and stress following the 2001 terrorist attacks.27 This may have led to increased rates of stress or depression in the controls in our study.

Chronic pelvic pain places a significant burden on the healthcare system, with outpatients costs totaling more than $880 million each year.28 As women with vulvodynia appear to see multiple clinicians and try numerous treatments,3 it was anticipated that study results would demonstrate the case population uses the healthcare system more frequently than controls. Interestingly, this hypothesis only was supported by univariate analysis. When healthcare variables were considered in conjunction with other factors, they were no longer significantly associated with disease. There was a concern that chronic yeast and urinary tract infections were so strongly correlated with vulvodynia that they prevented healthcare utilization variables from remaining in the model, but when a separate model was generated with only healthcare utilization variables, these univariate findings still did not emerge as significant predictors.

The failure to identify significant healthcare utilization predictors on the multivariate level may reflect the fact that case and control subjects were selected from a care-seeking population. For example, this study could only address that of those who had received the diagnosis of vulvodynia, they had seen “x” number of providers about their pain. This form of selection bias might reduce any effect of excess medical visits and missed days of work or school by cases because controls also sought care from the same clinical community. To further evaluate such care-seeking factors and explore burden of vulvodynia on the healthcare system and society as a whole, healthcare utilization trends of women with vulvodynia could be compared to data from the National Health Interview Survey.

This study demonstrates that vulvodynia substantially impacts quality of life and sexual health. Furthermore, the significant associations between vulvodynia and other chronic pain syndromes underscore the need for awareness among healthcare providers in asking detailed questions about conditions such as fibromyalgia and irritable bowel syndrome. A combination of awareness and better understanding of the relationship between vulvodynia and other (chronic) health disorders may enhance the management of women with this condition.

Table 2.

Characteristics of vulvar pain in 76 women with vulvodynia.*

| Women with Vulvodynia (n = 76)a | ||

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Age first experienced pain (n = 72) | ||

| Less than 20 years old | 14 | 19.4 |

| 20-24 years old | 17 | 23.6 |

| 30 years and older | 41 | 57.0 |

| Pain Descriptors† | ||

| Burning | 67 | 88.2 |

| Itching | 46 | 60.5 |

| Stinging | 40 | 52.6 |

| Aching | 37 | 48.7 |

| Stabbing | 31 | 40.8 |

| Perceived causes of pain‡ | ||

| “Other” | 31 | 40.8 |

| Unknown | 29 | 38.2 |

| Yeast infection | 22 | 28.9 |

| Stress | 19 | 25.0 |

| Diet | 8 | 10.5 |

| Exacerbating factors§ | ||

| Intercourse | 57 | 75.0 |

| Soaps | 31 | 40.8 |

| Tampons | 27 | 35.5 |

| Laundry detergents | 19 | 35.0 |

| Exercise | 21 | 27.6 |

| # of doctors seen for pain (n = 75) | ||

| None | 1 | 1.3 |

| 1-2 doctors | 15 | 20.0 |

| 3-4 doctors | 32 | 42.7 |

| 5-9 doctors | 23 | 30.7 |

| 10 or more doctors | 4 | 5.3 |

| Impact of vulvar pain on intercourse | ||

| Ever stopped intercourse due to pain (n = 73) | 66 | 90.4 |

| Ever feared intercourse due to pain (n = 73) | 62 | 84.9 |

| Currently no intercourse due to pain (n = 70) | 39 | 55.7 |

| Impact of pain on sex life (n = 75) | ||

| Extreme/disabling | 31 | 41.3 |

| Quite a bit | 29 | 38.7 |

| Moderate | 5 | 6.7 |

| Mild | 5 | 6.7 |

| Not at all | 5 | 6.7 |

| Degree one feels out of control of her life | ||

| Extreme/disabling | 4 | 5.6 |

| Quite a bit | 16 | 22.2 |

| Moderate | 11 | 15.3 |

| Mild | 18 | 25.0 |

| Not at all | 23 | 31.9 |

| Degree one feels out of control of her body | ||

| Extreme/disabling | 5 | 7.0 |

| Quite a bit | 23 | 32.4 |

| Moderate | 14 | 19.7 |

| Mild | 20 | 28.2 |

| Not at all | 9 | 12.7 |

Responses are based on n = 76 cases; 1 case did not answer pain questions and was excluded from this analysis

Subjects indicated all words that described their symptoms

Subjects indicated all factors that they perceived caused their vulvodynia

Subjects indicated all factors that exacerbate their vulvodynia

Footnotes

Funding: This study was funded by the National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development (NIH grant R01-HD040119).

Précis

Vulvodynia, correlated with history of chronic yeast vaginitis, urinary tract infection and poor quality of life, shows individual association with fibromyalgia and irritable bowel syndrome.

References

- 1.Moyal-Barracco M, Lynch PJ. 2003 ISSVD terminology and classification of vulvodynia: a historical perspective. J Reprod Med. 2004;49:772–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harlow BL, Stewart EG. A population-based assessment of chronic unexplained vulvar pain: have we underestimated the prevalence of vulvodynia? J Am Med Womens Assoc. 2003;58:82–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Metts JF. Vulvodynia and vulvar vestibulitis: challenges in diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 1999;59:1547–56. 1561-2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sadownik LA. Clinical profile of vulvodynia patients. A prospective study of 300 patients. J Reprod Med. 2000;45:679–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedrich EG., Jr Vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. J Reprod Med. 1987;32:110–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dillman DA. Mail and telephone surveys : the total design method. Wiley; New York: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salant P, Dillman DA. How to conduct your own survey. Wiley; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goetsch MF. Vulvar vestibulitis: prevalence and historic features in a general gynecologic practice population. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164:1609–14. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)91444-2. discussion 1614-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reed BD, Haefner HK, Punch MR, Roth RS, Gorenflo DW, Gillespie BW. Psychosocial and sexual functioning in women with vulvodynia and chronic pelvic pain. A comparative evaluation. J Reprod Med. 2000;45:624–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sackett S, Gates E, Heckman-Stone C, Kobus AM, Galask R. Psychosexual aspects of vulvar vestibulitis. J Reprod Med. 2001;46:593–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adanu RM, Haefner HK, Reed BD. Vulvar pain in women attending a general medical clinic in Accra, Ghana. J Reprod Med. 2005;50:130–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Danielsson I, Sjoberg I, Wikman M. Vulvar vestibulitis: medical, psychosexual and psychosocial aspects, a case-control study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79:872–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lamont J, Randazzo J, Farad M, Wilkins A, Daya D. Psychosexual and social profiles of women with vulvodynia. J Sex Marital Ther. 2001;27:551–5. doi: 10.1080/713846829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berglund AL, Nigaard L, Rylander E. Vulvar pain, sexual behavior and genital infections in a young population: a pilot study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002;81:738–42. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2002.810809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reed BD, Crawford S, Couper M, Cave C, Haefner HK. Pain at the Vulvar Vestibule: A Web-Based Survey. Am Soc for Colp and Cervical Path. 2004;8:48–57. doi: 10.1097/00128360-200401000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saito YA, Schoenfeld P, Locke GR., 3rd The epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome in North America: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1910–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolfe F, Ross K, Anderson J, Russell IJ, Hebert L. The prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia in the general population. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:19–28. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lynch PJ. Vulvodynia: a syndrome of unexplained vulvar pain, psychologic disability and sexual dysfunction. J Reprod Med. 1986;31:773–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bazelmans E, Vercoulen JH, Swanink CM, et al. Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Primary Fibromyalgia Syndrome as recognized by GPs. Fam Pract. 1999;16:602–4. doi: 10.1093/fampra/16.6.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.White KP, Harth M. Classification, epidemiology, and natural history of fibromyalgia. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2001;5:320–9. doi: 10.1007/s11916-001-0021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarma AV, Foxman B, Bayirli B, Haefner H, Sobel JD. Epidemiology of vulvar vestibulitis syndrome: an exploratory case-control study. Sex Transm Infect. 1999;75:320–6. doi: 10.1136/sti.75.5.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marinoff SC, Turner ML. Vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. Dermatol Clin. 1992;10:435–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bergeron S, Binik YM, Khalife S, Pagidas K. Vulvar vestibulitis syndrome: a critical review. Clin J Pain. 1997;13:27–42. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199703000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKay M. Vulvodynia. A multifactorial clinical problem. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:256–62. doi: 10.1001/archderm.125.2.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomas TG, Mundâe PF. A practical treatise on the diseases of women. Lea brothers & co.; Philadelphia: 1891. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aikens JE, Reed BD, Gorenflo DW, Haefner HK. Depressive symptoms among women with vulvar dysesthesia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:462–6. doi: 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00521-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Psychological and emotional effects of the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center--Connecticut, New Jersey, and New York, 2001. Jama. 2002;288:1467–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mathias SD, Kuppermann M, Liberman RF, Lipschutz RC, Steege JF. Chronic pelvic pain: prevalence, health-related quality of life, and economic correlates. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:321–7. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00458-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]