Abstract

Epidemic Vibrio cholerae possess the VPI (Vibrio pathogenicity island) essential virulence gene cluster. The VPI is 41.2 kb in size and encodes 29 potential proteins, several of which have no known function. We show that the VPI-encoded Orf4 is a predicted 34-kDa periplasmic protein containing a zinc metalloprotease motif. V. cholerae seventh-pandemic (El Tor) strain N16961 carrying an orf4 mutation showed no obvious difference relative to its parent in the production of cholera toxin and the toxin-coregulated pilus, motility, azocasein digestion, and colonization of infant mice. However, analysis of rabbit ileal loops revealed that the N16961 orf4 mutant is hypervirulent, causing increased serosal hemorrhage and reactogenicity compared to its parent. Histology revealed a widening of submucosa, with an increase in inflammatory cells, diffuse lymphatic vessel dilatation, edema, endothelial cell hypertrophy of blood vessels, blunting of villi, and lacteal dilatation with lymphocytes and polymorphonuclear leukocytes. The mutant could be complemented in vivo with an orf4 gene on a plasmid but not with an orf4 gene containing a site-directed mutation in the putative zinc metalloprotease motif. Although its mechanism of its action is being studied further, our results suggest that the Orf4 protein is a zinc metalloprotease that modulates the pathogenesis and reactogenicity of epidemic V. cholerae. Based on our findings, we name this VPI-encoded protein Mop (for modulation of pathogenesis).

Vibrio cholerae is responsible for the life-threatening diarrheal disease called cholera. Cholera is a major public health concern because of its high transmissibility and death-to-case ratio and its ability to occur in epidemic and pandemic forms (19, 31). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), an estimated 120,000 deaths from cholera occur globally every year (37), and cholera continues to be a scourge throughout much of the world, with seven global pandemics recorded since 1817 (31). The explosive epidemic nature and severity of the disease and the potential threat to food and water supplies have prompted the listing of V. cholerae as an organism in biological defense research.

Studies on the pathogenesis of V. cholerae have identified several critical virulence factors, such as cholera toxin (CT), which is primarily responsible for the profuse secretory diarrhea characteristic of the disease (6), and the toxin-coregulated pilus (TCP) essential colonization factor and receptor for the phage encoding CT (34, 36). The pathogenesis of V. cholerae is still not well understood, as live attenuated vaccines from which known toxin genes have been deleted still cause reactogenicity in human volunteers (12, 33). This suggests that other as yet unidentified factors are involved in the pathogenesis of V. cholerae.

The V. cholerae pathogenicity island (VPI) is found in all epidemic V. cholerae strains and is typically absent from nonpathogenic strains (20, 23). The VPI is thought to be one of the genetic factors required for the emergence of epidemic V. cholerae (20). The VPI has been completely sequenced in both sixth- and seventh-pandemic strains; it is 41.2 kb in size (21) and encodes 29 potential proteins (21), including those involved in the synthesis of TCP (34) and accessory colonization factors (30) and in virulence regulation (5, 8, 9, 15, 16, 24, 29). Evidence that the VPI contains a phage-like integrase, excises from the chromosome, and can be horizontally transferred suggests that it is phage-like in properties (4, 20, 22, 23). The VPI also encodes several open reading frames with unknown but presumably important function. In pursuit of our interests in the factors involved in the emergence, pathogenesis, and persistence of epidemic V. cholerae and pathogenicity islands, we hypothesized that the VPI-encoded Orf4 has a role in the pathogenesis of epidemic V. cholerae strains.

Computer analysis predicts Orf4 to be a zinc metalloprotease.

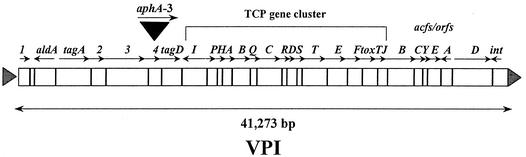

Orf4 is encoded on the VPI (Fig. 1). Computer analysis with PSORT predicts that orf4 is a single open reading frame which, after cleavage of a putative 18-amino-acid signal sequence, results in a potential secreted periplasmic protein of 34 kDa. Although a BLAST search (1, 2) found no homology of Orf4 with any protein in the database, a computer search of the PROSITE database found that Orf4 contains a conserved zinc metalloprotease motif (LVIHEFGHTL). These findings suggest that Orf4 is a periplasmic zinc metalloprotease. It is known that zinc metalloproteases are often involved in the pathogenesis of bacterial pathogens (11, 13, 14, 26, 28, 32, 35) and are often involved in virulence by either degrading eukaryotic host-cell proteins or by modifying bacterial proteins.

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the VPI in strain N16961, showing the location and the site of orf4 inactivation by the insertion of the aphA-3 gene encoding kanamycin resistance. Triangles flanking VP1 represent phage-like attachment (att) sites.

Cloning and mutagenesis of orf4.

In order to determine whether orf4 has a role in the pathogenesis of V. cholerae, we constructed an orf4 mutant. The V. cholerae strain N16961 (El Tor, serogroup O1), which was isolated in Bangladesh in 1971 and is a representative of the current seventh cholera pandemic which began in 1961 in Indonesia (25), was used in these studies. The predicted 939-bp orf4 from strain DK224, a spontaneous streptomycin-resistant (Smr) mutant derived from N16961, was amplified by PCR by using primers KAR268 (5′-TCATCGCAAGCTGATAGA-3′) and KAR67 (5′-ACCTACTTTAGGAAAAGAGCC-3′) on a 2.5-kb PCR product. The orf4 PCR product was then directly cloned into the TA cloning vector pGEM-T (Promega), creating plasmid pDK32, and confirmed by DNA sequencing. The 850-bp aphA-3 gene encoding kanamycin resistance and carried on pUC18K (27) was obtained by SmaI digestion. The aphA-3 gene was then blunt end ligated in-frame into the EcoRV site of pDK32, creating pDK44, which was confirmed by sequencing. Following SphI digestion, the 3.4-kb orf4::aphA-3 fragment was cloned into the suitably digested suicide plasmid pCVD442 (10), creating pDK46. With Escherichia coli strain SM10λpir(pDK46), allelic exchange was performed with the N16961 Smr strain DK224 to generate a nonpolar chromosomal orf4 Kmr mutant, designated DK297 (Fig. 1), which was confirmed by DNA sequencing. To construct a plasmid for complementation, orf4 was amplified on a 1.15-kb PCR fragment by using primers KAR453 (5′-CCCGAGCTCTTAGCTAATACACAAGGTCG-3′) and KAR455 (5′-CCCCCCGGGACACTACTTTAGTGTCACCG-3′), and the fragment was digested with SacI and SmaI and ligated into appropriately digested pWSK29, creating pDK102. Introduction of pDK102 into DK297, creating DK435, represented the complemented strain. Additionally, we constructed a site-directed mutation (His 224 Ala) in the putative zinc metalloprotease (LVIHEFGHTL) motif of orf4 on pDK102, creating pDK103. Plasmid pDK103 was transformed into DK297, creating DK436. We found no difference in the growth rate among the orf4 mutant (DK297), its parent (DK224), the complemented strain (DK435), and the site-directed mutant complemented strain (DK436).

The N16961 orf4 mutant is unaffected in CT, TCP, and motility in vitro.

For the determination of CT production, cell-free culture supernatant was obtained from strains grown in AKI broth at 37°C for 18 h with shaking at 200 rpm. The expression of CT was measured in microtiter plates by ganglioside enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (GM1-ELISA) by using rabbit anti-CT antisera and goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) (heavy plus light chains) conjugated with alkaline (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Inc.) and was read at an optical density of 405 nm. Statistical analysis was performed by using a one-way analysis of variance. We found no obvious difference between the orf4 mutant and its parent N16961 in CT production (data not shown). TCP production was assayed by Western blotting with a Supersignal kit and chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce) and was performed on whole-cell lysates by using cells from the cultures described above that were used for CT detection. Samples containing equal amounts of protein were run on 4 to 20% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis precast gels (Bio-Rad), transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (0.45-μm pore size) (17), and reacted with rabbit anti-TCP and goat anti-rabbit whole molecular IgG (Sigma). No obvious difference in TCP production was observed (data not shown). In addition, we found no difference in motility between DK224 and DK297 on 0.35% Luria-Bertani (LB) agar incubated at 37°C for 20 h.

Assay for protease activity and location of Orf4 in cell fractions.

We attempted to detect Orf4 protease activity in different cellular fractions of V. cholerae. In order to measure protease activity of the supernatants, an azocasein digestion assay was used (26). To prepare cell-free supernatants, strains were inoculated into 15-ml glass test tubes containing 3 ml of tryptic soy broth (and antibiotics when appropriate) and incubated at 37°C with shaking at 250 rpm for 6 h, after which 1 ml was transferred into a 1-liter flask containing 150 ml of fresh tryptic soy broth (and antibiotics when appropriate) and incubated at 30°C at 250 rpm for 24 h. Following centrifugation at 6,000 rpm in a Sorvall RC-5B machine for 20 min, the supernatants were filtered through 0.22-μm-pore-size filters (Millipore) and concentrated 20-fold with a Centricon-Plus 20 membrane (molecular weight, 10,000) at 4°C. For the azocasein digestion assay, 50 μl of supernatant was added to 800 μl of azocasein (2 mg/ml) in 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 160 μl of 50% trichloroacetic acid, and samples were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 15 min. The absorbance of the reaction was read at 366 nm on a Smartspec 3000 (Bio-Rad) spectrophotometer. We did not detect any significant difference in the protease activities of the (20-fold-concentrated) supernatants of DK224 and the orf4 mutant under the conditions tested (data not shown). In addition, Western blot analysis did not detect Orf4 in these supernatants with rabbit antisera generated against an orf4::His tag fusion protein.

To obtain periplasmic extracts, cell pellets were washed with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in 5 ml of PBS. Polymyxin B was then added at a final concentration of 2 mg/ml, the sample was stirred on ice for 20 min and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was collected and then concentrated 10-fold as described above. The pellet was resuspended in 5 ml of cold PBS, sonicated on ice five times at 7 W for 10-s intervals, and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm at 4°C for 10 min; the supernatant that was then collected represented the soluble extract. We did not detect any significant differences in the azocasein digestion activities in the periplasmic extracts or soluble extracts of N16961 and DK297 under these conditions, and we could not detect Orf4 in these factions by Western blotting (data not shown). These data suggest that Orf4 in N16961 has very low expression in vitro under the conditions tested.

The N16961 orf4 mutant is unaffected in the colonization in infant mice.

To determine whether orf4 has a role in intestinal colonization, a procedure based on the method of Baselski and Parker (3) was performed by using the infant mouse model. A single colony of DK224 and the orf4 mutant (DK297) was inoculated into 4 ml of LB broth containing appropriate antibiotics and incubated at 37°C overnight with shaking (250 rpm). The cultures were then centrifuged, and the cell pellets were washed twice with PBS, resuspended in PBS, and adjusted to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.4 (∼108 cells); then, 5 μl of blue food coloring per ml of culture was added. Just prior to mouse inoculation, the bacterial inocula were plated to determine the actual number of CFU/ml administered. Three-day-old suckling CD-1 mice were separated from their mothers 1 h prior to inoculation with V. cholerae. The mice were then orally inoculated with 100 μl (∼107 cells) of either DK224, DK297, or a mixture containing an equal amount of DK224 and DK297 (coinfection). Three groups of seven mice were used, with one group being used for each individual strain and one for the coinfection. Mice were sacrificed after 18 h, and their small and large intestines were removed, placed in 2 ml of PBS, and mechanically homogenized by using a Virsonic 60 (Virtis) blender; serial dilutions were then plated onto LB agar supplemented with appropriate antibiotics to enumerate V. cholerae CFU. Colonies obtained were streaked onto thiosulfate citrate bile salts agar to confirm their identity as V. cholerae. We found no difference in the levels of intestinal colonization by these V. cholerae strains (data not shown), which supported the TCP production results and suggests that Orf4 has no role in the intestinal colonization of infant mice by strain N16961.

Rabbit ileal loop studies demonstrate that Orf4 modulates pathogenesis in vivo.

We then studied whether orf4 had a role in pathogenesis by using the rabbit ileal loop model. In these studies, New Zealand White male rabbits (2 kg) (Covance Research Products) were used. Ligated ileal loops were performed essentially as described by De and Chatterjee (7) with strains DK224, DK297, JBK70 (a ctxAB mutant of N16961 [18]), DK435, and DK436. The strains to be tested were inoculated from frozen glycerol stocks into 4 ml of AKI broth (containing antibiotics where appropriate) and incubated at 37°C overnight at 180 rpm. Following incubation, 100 μl was transferred to a 250-ml flask containing 10 ml of AKI broth (containing antibiotics where appropriate) and incubated for 3 h at 37°C at 250 rpm. Bacterial cells were collected and washed twice with PBS; the cell density was adjusted to 107 CFU/ml, and cells were plated to confirm the number of CFU/ml. Prior to surgery, the rabbits were fasted for 24 h and fed only water ad libitum. The rabbits were anesthetized, a laparotomy was performed, and the small intestine was tied off into four loops (5 cm) with interloops (1 cm) between each main loop. By using a 25-gauge needle, 1 ml (107 cells) of solution containing either DK224, DK297, JBK70, DK435, or PBS as a control was inoculated into each loop. The intestine was returned to the peritoneal cavity, the incision was closed, and the rabbits were returned to their cage and given water ad libitum. The rabbits were sacrificed at 8 (n = 3) or 18 h (n = 6), the peritoneal cavity was opened, and the small intestine was removed. The loops were examined macroscopically; the fluid of each loop was removed and measured, and an aliquot was removed and plated onto LB agar containing appropriate antibiotics to determine the bacterial concentration (CFU/ml) and streaked onto thiosulfate citrate bile salts agar to confirm the cells' identity as V. cholerae. For histology, the loops were fixed in formalin, sectioned, stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and examined for histopathology. The fluid accumulation ratio (FAR) was determined by measuring the fluid (ml) in the loops and dividing by the length (cm) of the loop.

Experiments showed no difference in virulence between N16961 and DK224. Although there was no difference in the total number of V. cholerae cells per loop, examination of loops after 18 h with V. cholerae cells revealed obvious regions of serosal hemorrhage (redness), necrotic areas, pseudomembranous colitis (characterized by white flakey particles in the fluid), and fibrinopurulent tufts of exudate in the loop of each rabbit inoculated with DK297 (Fig. 2). No major serosal hemorrhage was observed in any other loop in any of the rabbits. Gross examination of the loops containing DK435 suggested that normal in vivo virulence could be restored after complementing the mutant with pDK102. However, pDK103, which contains a site-directed (H → A) mutation in the putative zinc metalloprotease (LVIHEFGHTL) motif of orf4, did not appear to restore wild-type virulence levels in DK297, further suggesting that the Orf4 protein is a zinc metalloprotease. While not statistically significant, we found only a slight increase in the FAR in the DK297 loop (2.4) compared to that in the DK224 loop (2.1) (Table 1). Similar findings in the level of serosal hemorrhage and the FAR in the DK297 loops were found in 8-h loops of three rabbits when the loop order was reversed (data not shown). Therefore, gross pathological changes were much greater in the loops inoculated with the orf4 mutant of N16961 than in those inoculated with its parent.

FIG. 2.

Gross examination of rabbit ileal loops revealed greater serosal hemorrhage in rabbit ileal loops inoculated with the orf4 (mop) mutant strain DK297. These results were consistent in rabbits after 8.5 (n = 3) and 18 (n = 6) h of incubation.

TABLE 1.

Virulence of the wild type and the orf4 mutant in rabbit ileal loopsa

| Sample | Effect on rabbit ileal loop

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vol (ml) | Length (cm) | FAR (vol/length) | Tissue damageb | |

| DK224 | 18 | 8.7 | 2.1 | −/+ |

| DK297 | 19.8 | 8.2 | 2.4 | +++ |

| JBK70 | 1.9 | 5.6 | 0.3 | − |

| PBS | 0.6 | 5.3 | 0.1 | − |

Results are based on 18-h ileal loops. Results for volume, length, and FAR are averages of values obtained from six rabbits.

Similar findings of serosal hemorrhage and particulate matter in loop fluid were observed in gross examination at 8 h. +, gross tissue damage; −, no visible gross tissue damage.

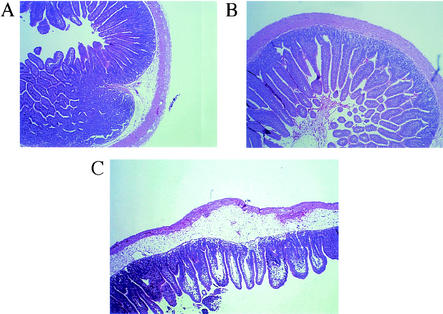

While histology showed that the tissue from loops containing DK224, JBK70, and PBS had a similar appearance, histology revealed obvious differences between the orf4 mutant and its parent DK224 (Fig. 3). The tissue of loops inoculated with DK224 appeared to be within normal limits, with only slight widening of submucosa. However, in sections from 18-h loops, the loops inoculated with the orf4 mutant DK297 generally demonstrated a widening of the submucosa, with an increase in heterophilic inflammatory cells in the mucosa, submucosa, muscularis, and serosa. Also characteristic of the DK297 loops were multifocal necrotic areas on the mucosa, diffuse lymphatic vessel dilatation, edema, and endothelial cell hypertrophy of the blood vessels. The villi multifocally demonstrated shortening and severe lacteal dilatation, with moderate amounts of inflammatory cells, including lymphocytes and lesser numbers of polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Introduction of pDK102 into DK297 restored histopathology to within normal limits. However, as described above, pDK103 did not appear to complement the orf4 mutation in vivo. These in vivo results suggest that the mutation of orf4 in N16961 results in a hypervirulent epidemic V. cholerae strain. The results also strongly suggest that orf4 has an important role in the pathogenesis of V. cholerae. Based on these findings, we propose to rename the VPI-encoded protein Mop (for modulation of pathogenesis).

FIG. 3.

Histology of ileal loops. Note the relatively normal tissue in loops inoculated with the N16961 Smr strain DK224 (A) and the ctxAB mutant JBK70 (B) compared to the increased pathological changes in loops in response to the orf4 (mop) mutant DK297 (C). For a description of pathological changes, see Results.

Comparison of sixth- and seventh-pandemic strains shows that relative to the products of other VPI genes, Mop (Orf4) has a higher level of variation (21). In that study, we found that the seventh-pandemic sequence differs from the sixth-pandemic sequence by 2.3% of its nucleotides and includes five amino acid differences. The amino acid polymorphisms in Mop between sixth- and seventh-pandemic strains include those that result in very different hydrophobicity properties. These differences might reflect functional differences in Mop expression between these strains and suggest that Mop might be under selective pressure in certain environments.

Although the exact function of Mop in epidemic V. cholerae is not fully understood and is being studied further, its predicted location in the periplasm or close to the bacterial cell surface would enable it to act on any secreted bacterial protein or any host cell factor and affect pathogenesis. Based on the results from this study, we propose that Mop, possibly in association with other factors, modulates the pathogenesis and reactogenicity of epidemic V. cholerae strains.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Karaolis lab for helpful discussions and David Acheson for reviewing the manuscript. We also thank Felicia Neuman and Srinivas Rao for assistance in performing rabbit surgeries and Mardi Reymann for technical assistance with CT ELISA assays. We are grateful to Genevieve Losonsky and Ron Taylor for supplying anti-CT and anti-TcpA antisera, respectively, and to Rick Milanich for photography assistance.

This work is supported by the NIH (grant AI45637 to D.K.R.K.) and by a Burroughs Wellcome Fund Career Award in the Biomedical Sciences (to D.K.R.K.).

Editor: B. B. Finlay

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, A. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baselski, V. S., and C. D. Parker. 1978. Intestinal distribution of Vibrio cholerae in orally infected infant mice: kinetics of recovery of radiolabel and viable cells. Infect. Immun. 21:518-525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyd, E. F., K. E. Moyer, L. Shi, and M. K. Waldor. 2000. Infectious CTXΦ and the vibrio pathogenicity island prophage in Vibrio mimicus: evidence for recent horizontal transfer between V. mimicus and V. cholerae. Infect. Immun. 68:1507-1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carroll, P. A., K. T. Tashima, M. B. Rogers, V. J. DiRita, and S. B. Calderwood. 1997. Phase variation in tcpH modulates expression of the ToxR regulon in Vibrio cholerae. Mol. Microbiol. 25:1099-1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De, S. N. 1959. Enterotoxicity of bacteria-free-culture-filtrate of Vibrio cholerae. Nature 183:1533-1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De, S. N., and D. N. Chatterjee. 1953. An experimental study of the mechanism of action of V. cholerae on the intestinal mucous membrane. J. Pathol. Bacteriol. 66:559-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DiRita, V. J. 1992. Co-ordinate expression of virulence genes by ToxR in Vibrio cholerae. Mol. Microbiol. 6:451-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DiRita, V. J., C. Parsot, G. Jander, and J. J. Mekalanos. 1991. Regulatory cascade controls virulence in Vibrio cholerae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:5403-5407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donnenberg, M. S., and J. B. Kaper. 1991. Construction of an eae deletion mutant of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli by using a positive-selection suicide vector. Infect. Immun. 59:4310-4317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finkelstein, R. A., M. Boesman-Finkelstein, Y. Chang, and C. C. Häse. 1992. Vibrio cholerae hemagglutinin/protease, colonial variation, virulence, and detachment. Infect. Immun. 60:472-478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fox, J. L. 1998. But cholera vaccine faces uphill struggle. ASM News 64:439-440. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Häse, C. C., and R. A. Finkelstein. 1993. Bacterial extracellular zinc-containing proteases. Microbiol. Rev. 57:823-837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Häse, C. C., and R. A. Finkelstein. 1991. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of the Vibrio cholerae hemagglutinin/protease (HA/protease) gene and construction of an HA/protease-negative strain. J. Bacteriol. 173:3311-3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Häse, C. C., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1998. TcpP protein is a positive regulator of virulence gene expression in Vibrio cholerae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:730-734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins, D. E., E. Nazareno, and V. J. DiRita. 1992. The virulence gene activator ToxT from Vibrio cholerae is a member of the AraC family of transcriptional activators. J. Bacteriol. 174:6974-6980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jonson, G., A. M. Svennerholm, and J. Holmgren. 1992. Analysis of expression of toxin-coregulated pili in classical and El Tor Vibrio cholerae O1 in vitro and in vivo. Infect. Immun. 60:4278-4284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaper, J. B., H. Lockman, M. M. Baldini, and M. M. Levine. 1984. Recombinant nontoxinogenic Vibrio cholerae strains as attenuated cholera vaccine candidates. Nature 308:655-658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaper, J. B., J. G. Morris, Jr., and M. M. Levine. 1995. Cholera. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 8:48-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karaolis, D. K. R., J. A. Johnson, C. C. Bailey, E. C. Boedeker, J. B. Kaper, and P. R. Reeves. 1998. A Vibrio cholerae pathogenicity island associated with epidemic and pandemic strains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:3134-3139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karaolis, D. K. R., R. Lan, J. B. Kaper, and P. R. Reeves. 2001. Comparison of Vibrio cholerae pathogenicity islands in sixth and seventh pandemic strains. Infect. Immun. 69:1947-1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karaolis, D. K. R., S. Somara, D. R. Maneval, Jr., J. A. Johnson, and J. B. Kaper. 1999. A bacteriophage encoding a pathogenicity island, a type-IV pilus and a phage receptor in cholera bacteria. Nature 399:375-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kovach, M. E., M. D. Shaffer, and K. M. Peterson. 1996. A putative integrase gene defines the distal end of a large cluster of ToxR-regulated colonization genes in Vibrio cholerae. Microbiology 142:2165-2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kovacikova, G., and K. Skorupski. 2000. Differential activation of the tcpPH promoter by AphB determines biotype specificity of virulence gene expression in Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 182:3228-3238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levine, M. M., R. E. Black, M. L. Clements, D. R. Nalin, L. Cisneros, and R. A. Finkelstein. 1981. Volunteer studies in development of vaccines against cholera and enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli: a review. In T. Holme, J. Holmgren, M. H. Merson, and R. Mollby (ed.), Acute enteric infections in children: new prospects for treatment and prevention. Elsevier/North-Holland Biomedical Press, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 26.Mel, S. F., K. J. Fullner, S. Wimer-Mackin, W. I. Lencer, and J. J. Mekalanos. 2000. Association of protease activity in Vibrio cholerae vaccine strains with decreases in transcellular epithelial resistance of polarized T84 intestinal epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 68:6487-6492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ménard, R., P. J. Sansonetti, and C. Parsot. 1993. Nonpolar mutagenesis of the ipa genes defines IpaB, IpaC, and IpaD as effectors of Shigella flexneri entry into epithelial cells. J. Bacteriol. 175:5899-5906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moncrief, J. S., R. Obiso, Jr., L. A. Barroso, J. J. Kling, R. L. Wright, R. L. Van Tassell, D. M. Lyerly, and T. D. Wilkins. 1995. The enterotoxin of Bacteroides fragilis is a metalloprotease. Infect. Immun. 63:175-181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ogierman, M. A., and P. A. Manning. 1992. Homology of TcpN, a putative regulatory protein of Vibrio cholerae, to the AraC family of transcriptional activators. Gene (Amsterdam) 116:93-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peterson, K. M., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1988. Characterization of the Vibrio cholerae ToxR regulon: identification of novel genes involved in intestinal colonization. Infect. Immun. 56:2822-2829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pollitzer, R. 1959. Cholera monograph, series 43. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [PubMed]

- 32.Smith, A. W., B. Chahal, and G. L. French. 1994. The human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori has a gene encoding an enzyme first classified as a mucinase in Vibrio cholerae. Mol. Microbiol. 13:153-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tacket, C. O., G. Losonsky, J. P. Nataro, S. J. Cryz, R. Edelman, A. Fasano, J. Michalski, J. B. Kaper, and M. M. Levine. 1993. Safety and immunogenicity of live oral cholera vaccine candidate CVD110, a ΔctxA Δzot Δace derivative of El Tor Ogawa Vibrio cholerae. J. Infect. Dis. 168:1536-1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor, R. K., V. L. Miller, D. B. Furlong, and J. J. Mekalanos. 1987. The use of phoA gene fusions to identify a pilus colonization factor coordinately regulated with cholera toxin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:2833-2837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Toma, C., Y. Ichinose, and M. Iwanaga. 1999. Purification and characterization of an Aeromonas caviae metalloprotease that is related to the Vibrio cholerae hemagglutinin/protease. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 170:237-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Waldor, M. K., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1996. Lysogenic conversion by a filamentous phage encoding cholera toxin. Science 272:1910-1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.World Health Organization. 2001. Cholera vaccines. Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 76:117-124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]