Abstract

Hormones that act through the calcium-releasing messenger, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3), cause intracellular calcium oscillations, which have been ascribed to calcium feedbacks on the IP3 receptor. Recent studies have shown that IP3 levels oscillate together with the cytoplasmic calcium concentration. To investigate the functional significance of this phenomenon, we have developed mathematical models of the interaction of both second messengers. The models account for both positive and negative feedbacks of calcium on IP3 metabolism, mediated by calcium activation of phospholipase C and IP3 3-kinase, respectively. The coupled IP3 and calcium oscillations have a greatly expanded frequency range compared to calcium fluctuations obtained with clamped IP3. Therefore the feedbacks can be physiologically important in supporting the efficient frequency encoding of hormone concentration observed in many cell types. This action of the feedbacks depends on the turnover rate of IP3. To shape the oscillations, positive feedback requires fast IP3 turnover, whereas negative feedback requires slow IP3 turnover. The ectopic expression of an IP3 binding protein has been used to decrease the rate of IP3 turnover experimentally, resulting in a dose-dependent slowing and eventual quenching of the Ca2+ oscillations. These results are consistent with a model based on positive feedback of Ca2+ on IP3 production.

INTRODUCTION

The release of Ca2+ ions from intracellular stores is a central event in the transduction of hormone and neurotransmitter signals. In a multitude of cell types, the activation of receptors coupled to the phosphoinositide pathway triggers oscillations in the cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]c). In many cell types, the strength of the extracellular stimulus is encoded primarily in the frequency of the [Ca2+]c oscillations, which increases with the degree of stimulation. For example, in rat hepatocytes, the periods of [Ca2+]c oscillations range over one order of magnitude, from >250 s for low concentrations of hormones, such as vasopressin and noradrenalin, to ∼30 s for higher hormone doses (1).

A long-standing question has been whether the oscillations are generated by the cellular Ca2+ transporters and channels themselves or whether they originate upstream in the signal transduction machinery, between hormone binding to its receptor and the activation of Ca2+ fluxes. It has been proposed that the periodic release of Ca2+ ions from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) can be brought about through the regulatory properties of the IP3 receptor (IP3R), the main type of ER calcium release channel in nonexcitable cells (2–5). Mathematical models have demonstrated how fast activation and delayed inhibition of the IP3R by cytoplasmic Ca2+ can drive repetitive Ca2+ spiking (6–8). In these models, IP3 is required to initially open the IP3R and sensitize the channel toward feedback activation by cytoplasmic calcium. Therefore, Ca2+ oscillations can occur when IP3 concentration is held at a constant value. However, models based on a simple description of the IP3R dynamics generally produce [Ca2+]c oscillations with short periods (∼10–60 s) and thus do not reproduce the long interspike intervals observed experimentally. Long-period oscillations have been obtained when additional mechanisms, such as the regulation of IP3R by phosphorylation, stochastic gating phenomena or slow calcium buffers, are included (9,10,11).

Recently, it has become possible to monitor IP3 changes in intact cells. These experiments have shown that, for some of the agonists used, the IP3 concentration is highly dynamic and can oscillate together with cytoplasmic calcium (12–15). This raises the intriguing possibility that a coupled IP3-Ca2+ oscillator may generate long-period oscillations and underlie the efficient frequency encoding of the hormone dose.

The existence of both positive and negative feedbacks of Ca2+ on IP3 metabolism could mediate fluctuations in cellular IP3 levels. The production of IP3 is catalyzed by a diverse family of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C (PLC) isoforms (16). All PLC isoforms are activated by Ca2+ ions, although their sensitivities to [Ca2+] vary greatly (17,18). This feedback can have an important role in Ca2+ wave propagation (19–22). IP3 is removed by phosphorylation or dephosphorylation through IP3 3-kinase (IP3K) or IP3 5-phosphatase (IP3P), respectively. IP3 removal by IP3K is activated by Ca2+ (23–25). Moreover, it has also been suggested that protein kinase C (PKC), which is activated by receptor-mediated increases in Ca2+ and diacylglycerol, may inhibit IP3 production by inactivating agonist receptors (13,26). However, it is presently not clear what effects such feedbacks have on Ca2+ oscillations. Importantly, it is not known whether the involvement of these Ca2+-dependent feedback mechanisms serves a physiological role.

Previous models have shown that IP3-mediated Ca2+ release coupled to Ca2+-activated PLC can generate oscillations, without any requirement of IP3R regulation by Ca2+ (26,27). These models have been criticized because in some cell types Ca2+ oscillations can also be elicited by IP3 or its nonmetabolizable analogs (3,28,29). The incorporation of Ca2+ activation of PLC into a Ca2+ oscillator model based on the above-described IP3R properties has been reported to modulate Ca2+ oscillations (30), whereas the inclusion of IP3K has been found to have practically no effect (31,32).

In this work, we have carried out a systematic modeling study of the interaction between cellular Ca2+ transports and IP3 metabolism. The model includes the dynamics of IP3, Ca2+, and IP3R and takes into account positive and negative feedback of Ca2+ on the IP3 metabolism. These are mediated by Ca2+ activation of IP3 generation through PLC and Ca2+ activation of IP3 removal by IP3K, respectively. We have found that each of these Ca2+ feedbacks strongly modifies the properties of a core oscillator based on Ca2+ and IP3R dynamics and, in particular, substantially expands the range of oscillation frequencies. Thus IP3 oscillations may underlie efficient frequency encoding of the hormone signal. The model analysis shows that the lifetime of IP3 is a critical parameter in the system, the experimental perturbation of which can give information on the feedbacks present. We directly tested this theory in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells by transiently expressing an IP3 binding protein composed of the N-terminal ligand-binding domain of the type 1 IP3R fused to green fluorescent protein. The overexpression of this fusion protein exerted a dose-dependent suppression of repetitive agonist-induced Ca2+ oscillations that is consistent with an oscillator model including positive feedback of Ca2+ on IP3 generation. Taken together, the experimental data and theoretical analysis suggest that IP3 oscillations are an essential component of the Ca2+ oscillator, expanding the richness in the message conveyed by extracellular stimuli.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mathematical model

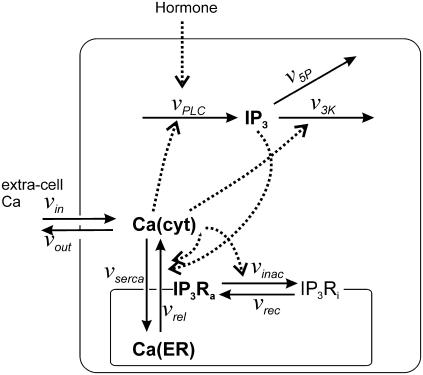

The model accounts for the formation and degradation of IP3, the main Ca2+ fluxes across the ER and plasma membrane, and the IP3R dynamics (see Fig. 1). It is formulated in terms of four variables: the IP3 and Ca2+ concentrations in the cytoplasm, p and c, respectively; the calcium concentration in the ER stores, s; and the fraction of IP3R that have not been inactivated by Ca2+, r.

FIGURE 1.

Interactions between Ca2+ transport processes and IP3 metabolism included in the model. The solid and dashed arrows indicate transport/reaction steps and activations, respectively. The bold quantities indicate the model variables: IP3, cytoplasmic IP3; Ca(cyt), free cytoplasmic Ca2+; Ca(ER), free Ca2+ in the ER; IP3Ra, active conformation of the IP3R. The other abbreviations denote: IP3Ri, inactive conformation of the IP3R;  rate of Ca2+ release through the IP3R;

rate of Ca2+ release through the IP3R;  active Ca2+ transport into the ER;

active Ca2+ transport into the ER;  and

and  rate of Ca2+-induced IP3R inactivation and recovery rate, respectively;

rate of Ca2+-induced IP3R inactivation and recovery rate, respectively;  production rate of IP3;

production rate of IP3;  and

and  rates of IP3 dephosphorylation and phosphorylation, respectively;

rates of IP3 dephosphorylation and phosphorylation, respectively;  and

and  rates of Ca2+ influx and extrusion across the plasma membrane, respectively.

rates of Ca2+ influx and extrusion across the plasma membrane, respectively.

IP3 dynamics

IP3 is produced by PLC, whose activity depends on agonist dose and Ca2+. The Ca2+ sensitivity of PLCβ can be modeled by (33)

|

(1) |

The maximal rate  depends on the agonist concentration, whereas

depends on the agonist concentration, whereas  characterizes the sensitivity of PLC to Ca2+. IP3 is removed through dephosphorylation by IP3P and phosphorylation by IP3K, which we model as

characterizes the sensitivity of PLC to Ca2+. IP3 is removed through dephosphorylation by IP3P and phosphorylation by IP3K, which we model as

|

(2) |

where  and

and  are the IP3 dephosphorylation and phosphorylation rate constants, respectively. The Ca2+ dependence of the IP3K is described by a Hill function with the half-saturation constant

are the IP3 dephosphorylation and phosphorylation rate constants, respectively. The Ca2+ dependence of the IP3K is described by a Hill function with the half-saturation constant  (23). According to Fink et al. (34) and Sims and Allbritton (35), one can assume that the two enzymes are not saturated with IP3, justifying the linear rate law in p.

(23). According to Fink et al. (34) and Sims and Allbritton (35), one can assume that the two enzymes are not saturated with IP3, justifying the linear rate law in p.

For the purpose of the subsequent analysis we write the balance equation for the IP3 concentration in the following form

|

(3) |

where we introduce the characteristic time of IP3 turnover

|

(4) |

and the ratio of the maximal IP3K rate to the total maximal degradation rate of IP3

|

(5) |

The strength of the positive feedback will be tuned by changing  (the Ca2+ sensitivity of PLC), and the strength of the negative feedback will be tuned by changing

(the Ca2+ sensitivity of PLC), and the strength of the negative feedback will be tuned by changing  (the relative expression level of IP3K). Although both feedbacks can be present simultaneously, it is useful to first analyze them separately. Therefore, we define the “positive-feedback model” in which PLC is sensitive to Ca2+ (

(the relative expression level of IP3K). Although both feedbacks can be present simultaneously, it is useful to first analyze them separately. Therefore, we define the “positive-feedback model” in which PLC is sensitive to Ca2+ ( ) and IP3K is not expressed (

) and IP3K is not expressed ( ), and the “negative-feedback model” in which IP3K is present (

), and the “negative-feedback model” in which IP3K is present ( ) and PLC is assumed insensitive to physiological Ca2+ changes (

) and PLC is assumed insensitive to physiological Ca2+ changes ( ).

).

Note that the rescaled maximal PLC activity  equals the steady-state concentration of IP3 that would be attained in the absence of positive or negative feedbacks.

equals the steady-state concentration of IP3 that would be attained in the absence of positive or negative feedbacks.

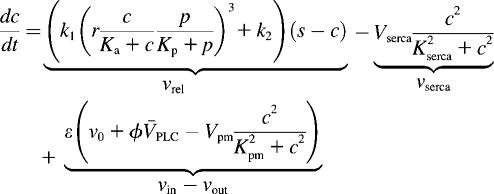

Calcium and IP3R dynamics

The Ca2+ release flux through the IP3R,  is modeled according to Li and Rinzel (36). The rate equations for active transport of Ca2+ across the ER and plasma membranes,

is modeled according to Li and Rinzel (36). The rate equations for active transport of Ca2+ across the ER and plasma membranes,  and

and  respectively, follow Lytton et al. (37) and Camello et al. (38). Calcium influx vin includes a leak into the cell and a stimulation dependent influx. The balance equation for cytoplasmic Ca2+ then reads

respectively, follow Lytton et al. (37) and Camello et al. (38). Calcium influx vin includes a leak into the cell and a stimulation dependent influx. The balance equation for cytoplasmic Ca2+ then reads

|

(6) |

The dimensionless parameter  measures the relative strength of the plasma membrane fluxes, which is known to be cell-type specific. We first carry out the model analysis for the simpler case that the plasma membrane fluxes are negligible. Setting

measures the relative strength of the plasma membrane fluxes, which is known to be cell-type specific. We first carry out the model analysis for the simpler case that the plasma membrane fluxes are negligible. Setting  the total Ca2+ concentration in the cell is conserved and can be expressed as

the total Ca2+ concentration in the cell is conserved and can be expressed as  where

where  is the ratio of effective cytoplasmic volume to effective ER volume (both accounting for Ca2+ buffering). Therefore, we can insert for the ER calcium in Eq. 6,

is the ratio of effective cytoplasmic volume to effective ER volume (both accounting for Ca2+ buffering). Therefore, we can insert for the ER calcium in Eq. 6,  In the presence of plasma-membrane fluxes (

In the presence of plasma-membrane fluxes ( ) this conservation no longer holds and a kinetic equation for s must be added:

) this conservation no longer holds and a kinetic equation for s must be added:

|

(7) |

The dynamics of IP3R inactivation by cytoplasmic Ca2+ is described by (35)

|

(8) |

The meaning and numerical values of the kinetic parameters are given in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Reference parameter values

| Positive feedback | Negative feedback | |

|---|---|---|

| IP3 dynamics parameters | ||

Half-activation constant of IP3K,

|

0.4 μM | 0.4 μM |

IP3 phosphorylation rate constant,

|

0 | 0.1 s−1 |

IP3 dephosphorylation rate constant,

|

0.66 s−1 | 0 |

Half-activation constant of PLC,

|

0.2 μM | 0 μM |

| Ca2+ transport and structural parameters | ||

| Ratio of effective volumes ER/cytosol, β | 0.185 | 0.185 |

Maximal SERCA pump rate,

|

0.9 μM s−1 | 0.25 μM s−1 |

Half-activation constant,

|

0.1 μM | 0.1 μM |

Maximal PMCA pump rate,

|

0.01 μM s−1 | 0.01 μM s−1 |

Half-activation constant,

|

0.12 μM | 0.12 μM |

Constant influx,

|

0.0004 μM/s | 0.0004 μM/s |

Stimulation-dependent influx,

|

0.0047 s−1 | 0.045 s−1 |

Strength of plasma membrane fluxes,

|

0 | 0 |

Total Ca2+ concentration (for  ), ),

|

2 μM | 2 μM |

| IP3R parameters | ||

| Maximal rate of Ca2+ release, k1 | 1.11 s−1 | 7.4 s−1 |

| Ca2+ leak, k2 | 0.0203 s−1 | 0.00148 s−1 |

Ca2+ binding to activating site,

|

0.08 μM | 0.2 μM |

Ca2+ binding to inhibiting site,

|

0.4 μM | 0.3 μM |

IP3 binding,

|

0.13 μM | 0.13 μM |

Characteristic time IP3R inactivation,

|

12.5 s | 6.6 s |

The half-saturation constants for PLC and IP3K were taken from Blank et al. (32) and Communi et al. (22), respectively. The IP3 degradation rate constants were chosen in accordance to Fink et al. (33) and Sims and Allbritton (34). The maximal rate of PLC,  is taken as the stimulation-dependent control parameter. In the positive-feedback model (Ca2+ activation of PLC), the parameters for the Ca2+ transport processes and the IP3R were taken from Li and Rinzel (35). In the negative feedback model (Ca2+ activation of IP3K), we obtained no substantial effect of the IP3K on the oscillations with these parameters. However, for different parameters (as given) the IP3K effects were pronounced. The differences in the Ca2+ fluxes between the two models can be accounted for by variations in the expression of the involved proteins. The differences in the Ca2+ binding properties to the activating site of the IP3R can be due to differences in the expression of IP3R subtypes, with IP3R subtype I having a higher Ca2+ dissociation constant for the activating site than subtypes II and III (52,53). The table gives the reference parameter set; parameters that are varied in specific simulations are indicated in the respective figure legends.

is taken as the stimulation-dependent control parameter. In the positive-feedback model (Ca2+ activation of PLC), the parameters for the Ca2+ transport processes and the IP3R were taken from Li and Rinzel (35). In the negative feedback model (Ca2+ activation of IP3K), we obtained no substantial effect of the IP3K on the oscillations with these parameters. However, for different parameters (as given) the IP3K effects were pronounced. The differences in the Ca2+ fluxes between the two models can be accounted for by variations in the expression of the involved proteins. The differences in the Ca2+ binding properties to the activating site of the IP3R can be due to differences in the expression of IP3R subtypes, with IP3R subtype I having a higher Ca2+ dissociation constant for the activating site than subtypes II and III (52,53). The table gives the reference parameter set; parameters that are varied in specific simulations are indicated in the respective figure legends.

Numerical solutions of the differential equations system, Eqs. 3 and 6–8, were obtained using a fourth-order Runge-Kutta algorithm implemented in XPPAUT (http://www.math.pitt.edu/∼bard/xpp/xpp.html). Bifurcation analyses were done using the program AUTO2000 (39). Calcium waves with the local kinetics given by Eqs. 3 and 6–8 and diffusion of Ca2+ and IP3 were calculated numerically with a finite-difference Crank-Nicholson scheme. Wave speeds for solitary waves were evaluated using AUTO2000.

Experimental procedures

Cell culture

CHO cells were cultured in Ham's F-12 media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics. Cells were seeded onto poly-D-lysine coated glass coverslips (25 mm) and maintained in culture until 70–80% confluent before experimental protocols.

Plasmid construction and transfection protocols

The cDNA encoding 620 amino acids of the N-terminal rat type 1 IP3 receptor (40) was ligated in-frame to the C-terminus of the enhanced green fluorescent protein gene in the plasmid pEGFP-C1 (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) to generate the plasmid pEGFP-LBD. Cell cultures were transiently transfected with either pEGFP-LBD (EGFP-LBD) or pEGFP-C1 (EGFP) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocols. Agonist-evoked [Ca2+]c responses were recorded in transfected cultures after a 16–48-h incubation period.

Imaging measurements of [Ca2+]c and fluorescent proteins

Calcium imaging experiments were performed in a HEPES-buffered physiological saline solution (HBSS) comprising (in mM): 25 HEPES (pH 7.4 at 37°C), 121 NaCl, 5 NaHCO3, 4.7 KCl, 1.2 KH2PO4, 1.2 MgSO4, 2.0 CaCl2, 10 glucose, 0.1 sulphobromophthalein, and 0.25% (w/v) fatty acid-free BSA. Cell cultures were loaded with fura-2/AM by incubation with 5 μM fura-2/AM plus Pluronic F-127 (0.02% v/v) for 20–40 min in HBSS. The cells were washed and transferred to a thermostatically regulated microscope chamber (37°C). Fura-2 fluorescence images (excitation, 340 and 380 nm, emission 420–600 nm) were acquired at 3–4-s intervals with a cooled charge-coupled device (CCD) camera as previously described (3). Fura-2 fluorescence intensities were corrected for GFP spillover before calculating fluorescence ratio values, by quenching cytosolic fura-2 with MnCl2. Cells expressing recombinant proteins were selected by screening for GFP fluorescence (excitation 488 nm, emission 525 nm).

EGFP-LBD concentration was estimated from a standard curve constructed with known concentrations of six His-tagged EGFP (Clontech; molecular weight of 27,000). Calibration solutions were prepared by diluting the recombinant protein in PBS. An aliquot (5 μl) was mixed with low-density mineral oil then sandwiched between two glass coverslips. EGFP containing “bubbles” ranging in size from 10 to 50 μm (the approximate range of cell diameters observed in CHO cultures) were imaged with a Nikon 20×, 0.75 NA Plan Apo objective on a wide-field microscope. The fluorophore protein concentration was converted into molar value assuming a molecular weight of 27,000 for His-tagged EGFP.

RESULTS

Positive and negative feedback models exhibit frequency encoding of agonist dose

In many cell types, one observes a strong dependence of the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations on the dose of the applied receptor agonist, whereas the oscillation amplitude remains nearly constant (1). A stepwise increase of the agonist concentration is accompanied by a prompt rise of the oscillation frequency. In the model, the maximal rate of PLC,  is a measure of agonist concentration. We subjected the positive-feedback model, with Ca2+ activation of PLC, and the negative-feedback model, with Ca2+ activation of IP3K, to stepwise increases in

is a measure of agonist concentration. We subjected the positive-feedback model, with Ca2+ activation of PLC, and the negative-feedback model, with Ca2+ activation of IP3K, to stepwise increases in  The responses are shown in Fig. 2, A and B, respectively, with the time points of

The responses are shown in Fig. 2, A and B, respectively, with the time points of  increase indicated by arrowheads. Both models exhibit a large range of oscillation frequencies with little change in [Ca2+]c amplitude (Fig. 2, A and B; top traces). The pronounced increase in the rate of spiking with increasing stimulus is the hallmark of the experimentally observed frequency encoding. For very large stimuli, a plateau of elevated [Ca2+]c is reached, again in agreement with experimental data.

increase indicated by arrowheads. Both models exhibit a large range of oscillation frequencies with little change in [Ca2+]c amplitude (Fig. 2, A and B; top traces). The pronounced increase in the rate of spiking with increasing stimulus is the hallmark of the experimentally observed frequency encoding. For very large stimuli, a plateau of elevated [Ca2+]c is reached, again in agreement with experimental data.

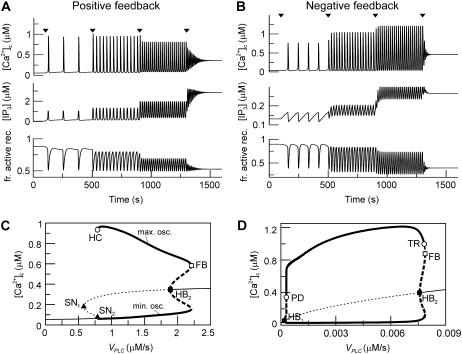

FIGURE 2.

Agonist-induced IP3 and Ca2+ oscillations in the positive and negative feedback models. (A) Positive feedback model with Ca2+ activation of PLC. Changes in [Ca2+]c, [IP3], and in the fraction of active receptors  (top, middle, and bottom panels) after stepwise increases in the agonist concentration (arrowheads), modeled by an increase in the maximal rate of PLC (

(top, middle, and bottom panels) after stepwise increases in the agonist concentration (arrowheads), modeled by an increase in the maximal rate of PLC ( for t < 100 with successive increases to 0.787, 1, 1.5, and 2.5 μM/s). (B) Negative feedback model with Ca2+ activation of IP3K. The response is shown for a step protocol with

for t < 100 with successive increases to 0.787, 1, 1.5, and 2.5 μM/s). (B) Negative feedback model with Ca2+ activation of IP3K. The response is shown for a step protocol with  for t < 100, followed by increases to 0.45, 2.5, 5.8, and 10 nM/s. (C) Bifurcation diagram for positive feedback model; shown are the maxima and minima of the [Ca2+]c oscillations (thick lines) and the [Ca2+]c steady states (thin lines) as a function of the stimulus (

for t < 100, followed by increases to 0.45, 2.5, 5.8, and 10 nM/s. (C) Bifurcation diagram for positive feedback model; shown are the maxima and minima of the [Ca2+]c oscillations (thick lines) and the [Ca2+]c steady states (thin lines) as a function of the stimulus ( ). Solid and dashed lines indicate stable and unstable states, respectively. HB, Hopf bifurcation; HC, homoclinic bifurcation; SN, saddle-node bifurcation; FB, saddle node of periodics. (D) Bifurcation diagram for negative feedback model. PD, period doubling; TR, torus bifurcation. Between PD and HB1 and TR and FB there exist complex oscillations (omitted for clarity). The parameter values used are listed in Table 1.

). Solid and dashed lines indicate stable and unstable states, respectively. HB, Hopf bifurcation; HC, homoclinic bifurcation; SN, saddle-node bifurcation; FB, saddle node of periodics. (D) Bifurcation diagram for negative feedback model. PD, period doubling; TR, torus bifurcation. Between PD and HB1 and TR and FB there exist complex oscillations (omitted for clarity). The parameter values used are listed in Table 1.

The [Ca2+]c oscillations in both models consist of a series of sharp spikes with baseline interludes (Fig. 2, A and B). The peak values of [Ca2+]c and [IP3] occur nearly at the same time. The shape of the [IP3] oscillations in the two models is different. In the positive-feedback model, [IP3] exhibits baseline-separated spikes (Fig. 2 A). In contrast, in the negative-feedback model, [IP3] follows a zig-zag pattern: the occurrence of a [Ca2+]c spike leads to an abrupt decrease in [IP3], after which [IP3] slowly builds up again over the whole oscillation period (Fig. 2 B). The IP3R activities show similar dynamics in both models.

The behavior of the two model systems for different stimulation strengths can be summarized in bifurcation diagrams (Fig. 2, C and D). We computed the steady states of [Ca2+]c and the maxima and minima of [Ca2+]c oscillations as a function of  For very low PLC activity, both models show a stable steady state of low [Ca2+]c; similarly, an elevated [Ca2+]c plateau is reached at relatively high PLC activity (these stable steady states are indicated by thin solid lines). For an intermediate range of

For very low PLC activity, both models show a stable steady state of low [Ca2+]c; similarly, an elevated [Ca2+]c plateau is reached at relatively high PLC activity (these stable steady states are indicated by thin solid lines). For an intermediate range of  the steady states are unstable (thin dashed lines). In these regions, both models exhibit oscillations ([Ca2+]c maxima and minima in stable oscillations are depicted by thick solid lines). The oscillations arise either via Hopf bifurcations (HB), or, in the case of the positive-feedback model, also by a homoclinic bifurcation (HC).

the steady states are unstable (thin dashed lines). In these regions, both models exhibit oscillations ([Ca2+]c maxima and minima in stable oscillations are depicted by thick solid lines). The oscillations arise either via Hopf bifurcations (HB), or, in the case of the positive-feedback model, also by a homoclinic bifurcation (HC).

Further bifurcations are indicated and referred to in the figure legend. In particular, a homoclinic bifurcation is associated with the existence of multiple steady states, which arise through saddle-node bifurcations (Fig. 2 C, SN). Such multistationarity is typical for models that neglect the plasma-membrane fluxes of calcium; this point will be discussed in more detail below. In the negative-feedback model, there are two regions near the Hopf bifurcations HB1 and HB2 (before the point PD and after the point TR in Fig. 2 D) where irregular and bursting oscillations are observed (results not shown). Because these two regions are extremely narrow, compared to the total stimulation range in the negative feedback model, our focus will be on the regular oscillations.

In the two bifurcation diagrams, one notices that the  values required for oscillations are considerably smaller in the negative-feedback model than in the positive-feedback model. This is primarily a consequence of the different feedback mechanisms. First, in the positive-feedback model the actual PLC activity is Ca2+ dependent and, therefore, is lower than

values required for oscillations are considerably smaller in the negative-feedback model than in the positive-feedback model. This is primarily a consequence of the different feedback mechanisms. First, in the positive-feedback model the actual PLC activity is Ca2+ dependent and, therefore, is lower than  at resting [Ca2+]c. Second, owing to the calcium activation of IP3K in the negative-feedback model, the IP3 degradation rate at resting [Ca2+]c is much smaller than in the positive-feedback model, requiring a smaller rate of IP3 production to raise [IP3] and induce oscillations.

at resting [Ca2+]c. Second, owing to the calcium activation of IP3K in the negative-feedback model, the IP3 degradation rate at resting [Ca2+]c is much smaller than in the positive-feedback model, requiring a smaller rate of IP3 production to raise [IP3] and induce oscillations.

The wide range of oscillation periods is due to interactions of IP3 and Ca2+ dynamics

To elucidate whether the IP3 dynamics participate in frequency encoding, we compared the oscillation periods in models without any Ca2+ feedback on IP3 (resulting in a constant [IP3]) and in the two feedback models (with [IP3] oscillations).

We begin by discussing the positive-feedback model. In the positive-feedback model, we consider Ca2+ activation of the agonist-dependent PLCβ. The strength of the positive feedback can be tuned by changing the value of the Ca2+ activation constant,  For

For  being much lower than the basal [Ca2+]c, PLC is always saturated with Ca2+ and its activity is independent of variations in [Ca2+]c. In particular, by setting

being much lower than the basal [Ca2+]c, PLC is always saturated with Ca2+ and its activity is independent of variations in [Ca2+]c. In particular, by setting  positive feedback will effectively be eliminated. This model with constant [IP3] shows fast calcium oscillations with a period of 10–15 s (Fig. 3 A, dashed line). Introducing positive feedback by setting

positive feedback will effectively be eliminated. This model with constant [IP3] shows fast calcium oscillations with a period of 10–15 s (Fig. 3 A, dashed line). Introducing positive feedback by setting  causes oscillations with long periods at low stimulation. The frequency encoding of the stimulus becomes very pronounced when the sensitivity of PLC to changes in [Ca2+]c is just above basal [Ca2+]c (Fig. 3 A, solid lines;

causes oscillations with long periods at low stimulation. The frequency encoding of the stimulus becomes very pronounced when the sensitivity of PLC to changes in [Ca2+]c is just above basal [Ca2+]c (Fig. 3 A, solid lines;  and 0.2 μM).

and 0.2 μM).

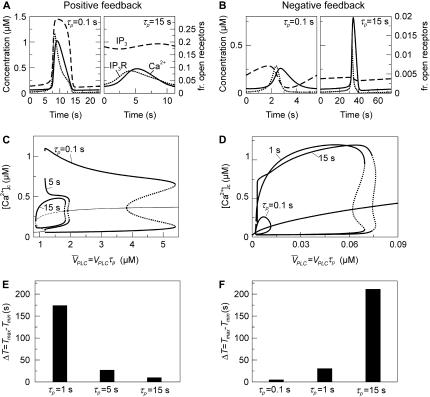

FIGURE 3.

Frequency encoding of agonist stimulus. (A) Positive feedback: oscillation periods observed at different stimulation strengths (varying  ). Increasing the half-saturation constant of PLC for Ca2+, KPLC, from 0 (no functional positive feedback) to 0.2 μM (functional feedback) greatly enhances frequency encoding. (B) Negative feedback. Increasing the amount of IP3K relative to IP3P (

). Increasing the half-saturation constant of PLC for Ca2+, KPLC, from 0 (no functional positive feedback) to 0.2 μM (functional feedback) greatly enhances frequency encoding. (B) Negative feedback. Increasing the amount of IP3K relative to IP3P ( ) enhances frequency encoding. (C, D) The feedback effects shown in panels A and B are preserved when plasma-membrane fluxes of Ca2+ are included in the models (

) enhances frequency encoding. (C, D) The feedback effects shown in panels A and B are preserved when plasma-membrane fluxes of Ca2+ are included in the models ( ). (E) Range of oscillation periods,

). (E) Range of oscillation periods,  in the presence (+) and absence (w/o) of positive feedback for two different strengths of the plasma-membrane Ca2+ fluxes (

in the presence (+) and absence (w/o) of positive feedback for two different strengths of the plasma-membrane Ca2+ fluxes ( ). (F) Range of oscillation periods in the presence (−) and absence (w/o) of negative feedback for two different strengths of the plasma-membrane Ca2+ fluxes (

). (F) Range of oscillation periods in the presence (−) and absence (w/o) of negative feedback for two different strengths of the plasma-membrane Ca2+ fluxes ( ). We have found that the IP3K has an impact on the oscillation period only when the Ca2+ fluxes between ER and cytoplasm are comparatively slow and the IP3R is less sensitive to Ca2+ activation. To expose the period effect of the negative feedback, we have chosen different parameter values than in the positive feedback model (see Table 1).

). We have found that the IP3K has an impact on the oscillation period only when the Ca2+ fluxes between ER and cytoplasm are comparatively slow and the IP3R is less sensitive to Ca2+ activation. To expose the period effect of the negative feedback, we have chosen different parameter values than in the positive feedback model (see Table 1).

For the negative-feedback model, we recall that there are two removal pathways for IP3, one catalyzed by the Ca2+-insensitive IP3 5-phosphatase (IP3P) and the other by the Ca2+-activated IP3 3-kinase (IP3K). We can modify the strength of the negative feedback by taking different concentration ratios of IP3P and IP3K. The feedback strength is expressed by the ratio of the maximal IP3K rate to the total degradation rate of IP3;  where

where  has been kept constant in the following calculations. The oscillation periods in the absence of negative feedback (

has been kept constant in the following calculations. The oscillation periods in the absence of negative feedback ( ), and therefore constant [IP3], are shown in Fig. 3 B (dashed line). When

), and therefore constant [IP3], are shown in Fig. 3 B (dashed line). When  is sufficiently high, the negative feedback has a pronounced effect on the range of oscillations periods; for

is sufficiently high, the negative feedback has a pronounced effect on the range of oscillations periods; for  there is an increase in the period range (Fig. 3 B, solid lines).

there is an increase in the period range (Fig. 3 B, solid lines).

In the positive-feedback model, arbitrarily long periods can be obtained (exceeding the 200 s shown), which are due to the onset of the oscillations via a homoclinic bifurcation (see also Fig. 2 C). The homoclinic bifurcation specifically occurs in the model when the plasma-membrane fluxes of Ca2+ are neglected, which is a valid simplification for many cell types in which the contribution of these fluxes to Ca2+ oscillations is small (41). We have also studied the more general case when the plasma-membrane Ca2+ fluxes are included in the model (see Materials and Methods). Then there is a unique steady state and the homoclinic bifurcation no longer exists. Nevertheless, long-period oscillations are present (Fig. 3 C). Importantly, the dependence of the period range of the oscillations on  remains very similar.

remains very similar.

We also introduced plasma-membrane fluxes of Ca2+ into the negative-feedback model (Fig. 3 D). We observed a similar picture as without plasma membrane fluxes, provided that the plasma-membrane fluxes were comparatively moderate. However, when the plasma-membrane Ca2+ fluxes are large enough, the effect of IP3K on the oscillation period practically disappears. In contrast, the period behavior in the positive-feedback model is less affected by changes in the magnitude of the plasma-membrane Ca2+ fluxes. To show this, we evaluated the range of oscillation periods  where Tmax and Tmin are the maximal and minimal period that are obtained for low and high stimulation, respectively, for two different strengths of the plasma-membrane Ca2+ fluxes (

where Tmax and Tmin are the maximal and minimal period that are obtained for low and high stimulation, respectively, for two different strengths of the plasma-membrane Ca2+ fluxes ( and

and  ). The positive-feedback model exhibits in both cases a much larger period range than the corresponding model without feedback (Fig. 3 E). In contrast, the increase of the period range through negative feedback is only seen when the plasma-membrane Ca2+ fluxes are comparatively small,

). The positive-feedback model exhibits in both cases a much larger period range than the corresponding model without feedback (Fig. 3 E). In contrast, the increase of the period range through negative feedback is only seen when the plasma-membrane Ca2+ fluxes are comparatively small, (Fig. 3 F).

(Fig. 3 F).

In summary, both positive and negative feedbacks of Ca2+ on IP3 may serve a physiological role by greatly enhancing the range of frequency encoding of the agonist stimulus. The frequency encoding supported by the positive feedback is more robust against variations in the kinetic parameters of the Ca2+ transport processes.

Positive and negative models respond differently to changes in feedback IP3 turnover time

In the model simulations, we noticed that the characteristic time of IP3 turnover  has a decisive impact on the Ca2+-IP3 oscillators. The measured IP3 turnover times span a relatively wide range, from 0.1 to >10 s depending on cell type and experimental conditions (34,35). We have found that fast IP3 turnover (

has a decisive impact on the Ca2+-IP3 oscillators. The measured IP3 turnover times span a relatively wide range, from 0.1 to >10 s depending on cell type and experimental conditions (34,35). We have found that fast IP3 turnover ( ) is associated with long oscillation periods in the positive-feedback model. Conversely, the negative-feedback model exhibits long-period oscillations when the IP3 turnover is comparatively slow (

) is associated with long oscillation periods in the positive-feedback model. Conversely, the negative-feedback model exhibits long-period oscillations when the IP3 turnover is comparatively slow ( ).

).

Insight into the origin of this difference between the two models can be gained by looking at the time courses of the model variables. In the positive feedback model, fast IP3 turnover ( ) yields high-amplitude oscillations in [Ca2+]c and [IP3] (Fig. 4 A, solid and dashed lines, respectively). [Ca2+]c and [IP3] rise simultaneously, and IP3-induced Ca2+ release and Ca2+-activated IP3 production coincide. After termination of the [Ca2+]c spike, [IP3] returns quickly to a basal level, because Ca2+-activated IP3 production has ceased and IP3 degradation is fast. Also, the IP3Rs close efficiently after the spike (Fig. 4 A, dotted line showing the fraction of open IP3R). For slow IP3 turnover (

) yields high-amplitude oscillations in [Ca2+]c and [IP3] (Fig. 4 A, solid and dashed lines, respectively). [Ca2+]c and [IP3] rise simultaneously, and IP3-induced Ca2+ release and Ca2+-activated IP3 production coincide. After termination of the [Ca2+]c spike, [IP3] returns quickly to a basal level, because Ca2+-activated IP3 production has ceased and IP3 degradation is fast. Also, the IP3Rs close efficiently after the spike (Fig. 4 A, dotted line showing the fraction of open IP3R). For slow IP3 turnover ( ) [IP3] does not sufficiently decline after the [Ca2+]c spike, leading to an increased basal opening of the IP3R, lower ER Ca2+ store loading and, consequently, much less pronounced [Ca2+]c spikes (Fig. 4 A).

) [IP3] does not sufficiently decline after the [Ca2+]c spike, leading to an increased basal opening of the IP3R, lower ER Ca2+ store loading and, consequently, much less pronounced [Ca2+]c spikes (Fig. 4 A).

FIGURE 4.

IP3 turnover time controls feedbacks. (A) Positive-feedback model. Dynamics of [Ca2+]c, [IP3], and the fraction of open IP3Rs (solid, dashed, and dot-dashed lines, respectively) during an oscillation period; the fraction of open IP3Rs is given by  (see Eq. 6). Fast IP3 turnover yields a pronounced spike (left panel,

(see Eq. 6). Fast IP3 turnover yields a pronounced spike (left panel,  ), whereas slow IP3 turnover supports only a small-amplitude response (right panel,

), whereas slow IP3 turnover supports only a small-amplitude response (right panel,  ). (B) The negative-feedback model shows the opposite behavior, with a small-amplitude response for fast IP3 turnover (left panel,

). (B) The negative-feedback model shows the opposite behavior, with a small-amplitude response for fast IP3 turnover (left panel,  ) and a sharp spike for slow IP3 turnover (left panel,

) and a sharp spike for slow IP3 turnover (left panel,  ). (C) Positive-feedback model. Bifurcation diagram showing the maxima and minima of the [Ca2+]c oscillations as a function of the stimulus for different values of the IP3 turnover. The bifurcation diagrams for different values of

). (C) Positive-feedback model. Bifurcation diagram showing the maxima and minima of the [Ca2+]c oscillations as a function of the stimulus for different values of the IP3 turnover. The bifurcation diagrams for different values of  are compared by plotting them against the product

are compared by plotting them against the product  ; in this way, the steady-state concentrations of Ca2+ and IP3 are identical for a given

; in this way, the steady-state concentrations of Ca2+ and IP3 are identical for a given  (solid and dashed lines indicate stable and unstable states, respectively; the stability of the steady state is shown for

(solid and dashed lines indicate stable and unstable states, respectively; the stability of the steady state is shown for  ). Both amplitude and range of stimuli leading to oscillations increase with faster IP3 turnover. (D) The corresponding bifurcation diagrams for the negative-feedback model show the opposite behavior. The amplitude and range of stimuli leading to oscillations increase with slower IP3 turnover. (E, F) Dependence of frequency encoding on IP3 turnover in the positive and negative feedback models, respectively. Shown are the differences

). Both amplitude and range of stimuli leading to oscillations increase with faster IP3 turnover. (D) The corresponding bifurcation diagrams for the negative-feedback model show the opposite behavior. The amplitude and range of stimuli leading to oscillations increase with slower IP3 turnover. (E, F) Dependence of frequency encoding on IP3 turnover in the positive and negative feedback models, respectively. Shown are the differences  between the largest (for low stimulation) and smallest (for high stimulation) oscillation period.

between the largest (for low stimulation) and smallest (for high stimulation) oscillation period.

Not only the spike characteristics but also the oscillation period and the range of agonist stimuli that give oscillations are affected by the IP3 half-life. For fast IP3 turnover, oscillations in the positive-feedback model are observed over a wide range of stimuli (Fig. 4 C,  ). Slower IP3 turnover leads to reduced oscillation ranges and also much smaller amplitudes (Fig. 4 C,

). Slower IP3 turnover leads to reduced oscillation ranges and also much smaller amplitudes (Fig. 4 C,  and 15 s). Importantly, also, the capacity for frequency encoding of the stimulus, as measured by the period range of oscillations, is high when the IP3 turnover is fast (Fig. 4 E).

and 15 s). Importantly, also, the capacity for frequency encoding of the stimulus, as measured by the period range of oscillations, is high when the IP3 turnover is fast (Fig. 4 E).

In the negative-feedback model, changing the timescale of IP3 turnover has the opposite effect. When IP3 turnover is fast ( ), a rise in [Ca2+]c triggers, via activation of IP3K, a pronounced decrease in [IP3], which in turn limits further Ca2+ release (Fig. 4 B). Therefore, the [Ca2+]c spikes are relatively small and [IP3] shows strong variations (solid and dashed lines, respectively, in Fig. 4 B). When the IP3 lifetime is larger (

), a rise in [Ca2+]c triggers, via activation of IP3K, a pronounced decrease in [IP3], which in turn limits further Ca2+ release (Fig. 4 B). Therefore, the [Ca2+]c spikes are relatively small and [IP3] shows strong variations (solid and dashed lines, respectively, in Fig. 4 B). When the IP3 lifetime is larger ( ), [IP3] remains at a relatively high level throughout and the [Ca2+]c spikes are accordingly more pronounced (Fig. 4 B). Moreover, for slow IP3 degradation, the range of stimuli where oscillations occur is larger (Fig. 4 D). The capacity for frequency encoding as measured by the range of oscillation periods,

), [IP3] remains at a relatively high level throughout and the [Ca2+]c spikes are accordingly more pronounced (Fig. 4 B). Moreover, for slow IP3 degradation, the range of stimuli where oscillations occur is larger (Fig. 4 D). The capacity for frequency encoding as measured by the range of oscillation periods,  strongly increases with the IP3 half-life (Fig. 4 F). This finding agrees with the frequent observation that negative feedback is more prone to oscillate when the controlled variable (here IP3) responds slowly.

strongly increases with the IP3 half-life (Fig. 4 F). This finding agrees with the frequent observation that negative feedback is more prone to oscillate when the controlled variable (here IP3) responds slowly.

To summarize, frequency encoding in the two feedback models poses opposite requirements on IP3 turnover: positive and negative feedbacks are efficient frequency modulators when the IP3 turnover is fast and slow, respectively. The critical IP3 lifetimes estimated in the model indicate that both cases could be realized physiologically.

Period control is shared by all processes

The calculations have shown that the inclusion of IP3 dynamics strongly alters the frequency properties of the oscillator and, particularly, leads to long-period oscillations. We have, therefore, quantified the control of the IP3 dynamics and the other processes present in the model on the oscillation period. To this end, we have used the following sensitivity measure

|

(9) |

which we refer to as period control coefficients (see also Wolf et al. (42)). The  set the change of the oscillation period T in proportion to the change in the characteristic time

set the change of the oscillation period T in proportion to the change in the characteristic time  of an individual process i. We analyzed the control of the following processes: IP3 metabolism (with

of an individual process i. We analyzed the control of the following processes: IP3 metabolism (with  as defined in Eqs. 3 and 4), the IP3R dynamics (with

as defined in Eqs. 3 and 4), the IP3R dynamics (with  as defined in Eq. 8), Ca2+ transport across the ER membrane (achieved by scaling

as defined in Eq. 8), Ca2+ transport across the ER membrane (achieved by scaling  with

with  in Eq. 6), and Ca2+ transport across the plasma membrane (achieved by scaling

in Eq. 6), and Ca2+ transport across the plasma membrane (achieved by scaling  with

with  in Eq. 6). A positive period control coefficient implies that a slowing of the respective process (i.e., increase in

in Eq. 6). A positive period control coefficient implies that a slowing of the respective process (i.e., increase in  ) raises the period. At any point, the period control coefficients sum to unity,

) raises the period. At any point, the period control coefficients sum to unity,  so that each coefficient quantifies the relative contribution of a single process to the oscillation period (43).

so that each coefficient quantifies the relative contribution of a single process to the oscillation period (43).

The control coefficients were calculated for various levels of stimulation in the positive and negative feedback models. Because these levels correspond to different oscillation periods, we can plot the Ci against the period. Fig. 5, A and B, depict the result for the model without plasma-membrane fluxes of Ca2+ ( ). Positive and negative feedback models yield a similar picture. The control is distributed between the dynamics of IP3, Ca2+, and IP3R. In long-period oscillations, the IP3 turnover has the leading control (dot-dashed lines). The IP3R dynamics contributes more significantly to setting the period of fast oscillations, especially in the positive-feedback model (dotted lines).

). Positive and negative feedback models yield a similar picture. The control is distributed between the dynamics of IP3, Ca2+, and IP3R. In long-period oscillations, the IP3 turnover has the leading control (dot-dashed lines). The IP3R dynamics contributes more significantly to setting the period of fast oscillations, especially in the positive-feedback model (dotted lines).

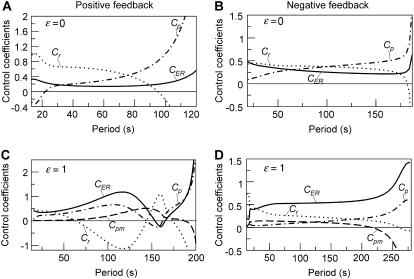

FIGURE 5.

Control coefficients for the oscillation period. (A, B) Positive and negative feedback models, respectively, in the absence of Ca2+ fluxes across the plasma membrane ( ); control coefficients of Ca2+ exchange across the ER membrane (Cer, solid line), IP3 metabolism (Cp, dashed line), and IP3R dynamics (Cr, dotted line) as function of the period of the oscillations. A positive period control coefficient signifies that a slowing of the corresponding process increases the oscillation period. (C, D) Period control coefficients in the positive and negative feedback models, respectively, in the presence of plasma-membrane fluxes of Ca2+ (

); control coefficients of Ca2+ exchange across the ER membrane (Cer, solid line), IP3 metabolism (Cp, dashed line), and IP3R dynamics (Cr, dotted line) as function of the period of the oscillations. A positive period control coefficient signifies that a slowing of the corresponding process increases the oscillation period. (C, D) Period control coefficients in the positive and negative feedback models, respectively, in the presence of plasma-membrane fluxes of Ca2+ ( ). The dash-dotted line indicates the control exerted by Ca2+ exchange across the plasma membrane (Cpm).

). The dash-dotted line indicates the control exerted by Ca2+ exchange across the plasma membrane (Cpm).

The distribution of control becomes more complex when the plasma-membrane fluxes of Ca2+ are included (Fig. 5, C and D;  ), although, interestingly, the plasma-membrane fluxes exert very little period control themselves (dashed lines). There are several notable features. First, the fast oscillations in the positive-feedback model are no longer dominated by the IP3R dynamics. There is even a rather counterintuitive behavior at intermediate periods where acceleration of the IP3R dynamics would result in a slowing of the oscillations (

), although, interestingly, the plasma-membrane fluxes exert very little period control themselves (dashed lines). There are several notable features. First, the fast oscillations in the positive-feedback model are no longer dominated by the IP3R dynamics. There is even a rather counterintuitive behavior at intermediate periods where acceleration of the IP3R dynamics would result in a slowing of the oscillations ( ). Second, the overall tendency that the IP3 dynamics are more relevant for slow oscillations is preserved. However, the dynamics of ER Ca2+ release and refilling now play a more pronounced role in setting the period.

). Second, the overall tendency that the IP3 dynamics are more relevant for slow oscillations is preserved. However, the dynamics of ER Ca2+ release and refilling now play a more pronounced role in setting the period.

This quantification of period control reveals that no process can be singled out as a unique period controlling factor. Depending on the oscillation mechanism and the reference period, the IP3 turnover, the ER Ca2+ fluxes, and the IP3R dynamics can all exert strong control.

How to distinguish Ca2+ feedbacks on IP3 metabolism experimentally: model predictions

Our analysis has shown that oscillation mechanisms involving Ca2+-activated PLC or IP3K are sensitive to the timescale of IP3. This offers the possibility to experimentally interfere with the oscillation mechanism by perturbing the IP3 turnover.

The overexpression of IP3 metabolizing enzymes would accelerate the IP3 turnover and also decrease [IP3] (see Eqs. 3–5). Overexpression of either IP3 5-phosphatase or IP3 3-kinase can abolish Ca2+ and IP3 oscillations. In the case of IP3P overexpression, this effect can be revoked by an increase in agonist dose, while quenching of oscillations with overexpression of the Ca2+-dependent IP3K is predicted to be irreversible. However, positive- and negative-feedback models behave in the same way (see Supplementary Material, Fig. S1).

A different result is obtained if the IP3 turnover is slowed by introducing IP3-binding proteins (IP3 buffer) into the cell. To be specific, we assume a monovalent IP3 buffer with on- and off-rate constants  and

and  respectively. The IP3 balance equation (Eq. 3) is then modified to

respectively. The IP3 balance equation (Eq. 3) is then modified to

|

(10a,b) |

where p as before stands for [IP3], B denotes the total concentration of the introduced IP3 buffer, and C is the concentration of occupied IP3 buffer. If the binding of IP3 to the buffer is fast compared to the IP3 degradation rate, the amount of occupied buffer will be in equilibrium with [IP3]. This implies  where

where  is the dissociation constant. Summing Eqs. 10a and 10b, and using the equilibrium relation for C, one obtains for the dynamics of unbound IP3

is the dissociation constant. Summing Eqs. 10a and 10b, and using the equilibrium relation for C, one obtains for the dynamics of unbound IP3

|

(11) |

with the modified characteristic time of IP3 turnover

|

(12) |

The IP3 buffer creates an additional bound pool of IP3 that is protected from degradation. Then the buildup of free [IP3] after PLC activation is delayed, because the buffer binding sites also need to be filled. Similarly, the decay of free [IP3] is slowed, because IP3 molecules dissociate from the buffer as cellular [IP3] decreases. Precisely these two effects are accounted for by the modified time constant  which increases with the buffer concentration (Eq. 12). Note that the balance between the rates of IP3 production and degradation is unaffected by the buffer. In particular, the IP3 buffer would not change the steady-state concentration of free IP3 attained when

which increases with the buffer concentration (Eq. 12). Note that the balance between the rates of IP3 production and degradation is unaffected by the buffer. In particular, the IP3 buffer would not change the steady-state concentration of free IP3 attained when  (The endogenous IP3 binding sites have already been accounted for by the characteristic time of IP3 turnover,

(The endogenous IP3 binding sites have already been accounted for by the characteristic time of IP3 turnover,  defined in the absence of the exogenous IP3 buffer.)

defined in the absence of the exogenous IP3 buffer.)

Introducing an exogenous IP3 buffer into a core Ca2+ oscillator model operating with constant PLC activity and Ca2+-insensitive degradation (such as the model discussed above in the absence of Ca2+ feedbacks on IP3), will delay the rise in [IP3] after PLC activation. However, eventually the same steady-state concentration of free [IP3] would be reached as without buffer. Therefore, Ca2+ oscillations may set in with an increased latency, whereas spike shape and period would be unaffected by the presence of the IP3 buffer.)

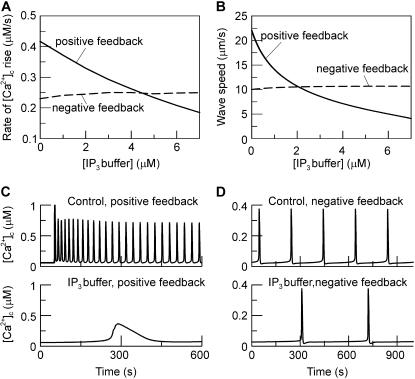

When introducing the IP3 buffer into the positive- and negative-feedback models, we find that for low concentrations of IP3 buffer (0 < B < 10 μM for  ) the oscillations persist in both models. However, depending on which type of Ca2+ feedback is present, IP3 buffer affects the kinetic properties of the [Ca2+]c oscillations in very different ways. In the positive-feedback model, the IP3 buffer slows the Ca2+ responses. The rate of [Ca2+]c rise in an individual spike is predicted to be decreased by the buffer in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6 A, solid line). Another characteristic property of [Ca2+]c oscillations is the wave speed—the velocity at which a calcium spike propagates through the cell. To evaluate the effect of IP3 buffer on wave propagation, we added to the model diffusion of Ca2+ and IP3 in the cytoplasm and solved the resulting reaction-diffusion equations numerically on a one-dimensional domain. The propagation speed of a Ca2+ spike shows a very similar behavior as the rate of [Ca2+]c rises: it decreases strongly as a function of IP3 buffer concentration in the positive-feedback model (Fig. 6 B, solid line). In contrast, in the negative-feedback model, the IP3 buffer will cause hardly perceptible increases in the rate of Ca2+ rise (Fig. 6 A, dashed line) and the wave speed (Fig. 6 B, dashed line). These two properties are well suited for experimental measurements, because they have been found to be remarkably constant in cells not perturbed by IP3 buffer (44–46).

) the oscillations persist in both models. However, depending on which type of Ca2+ feedback is present, IP3 buffer affects the kinetic properties of the [Ca2+]c oscillations in very different ways. In the positive-feedback model, the IP3 buffer slows the Ca2+ responses. The rate of [Ca2+]c rise in an individual spike is predicted to be decreased by the buffer in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6 A, solid line). Another characteristic property of [Ca2+]c oscillations is the wave speed—the velocity at which a calcium spike propagates through the cell. To evaluate the effect of IP3 buffer on wave propagation, we added to the model diffusion of Ca2+ and IP3 in the cytoplasm and solved the resulting reaction-diffusion equations numerically on a one-dimensional domain. The propagation speed of a Ca2+ spike shows a very similar behavior as the rate of [Ca2+]c rises: it decreases strongly as a function of IP3 buffer concentration in the positive-feedback model (Fig. 6 B, solid line). In contrast, in the negative-feedback model, the IP3 buffer will cause hardly perceptible increases in the rate of Ca2+ rise (Fig. 6 A, dashed line) and the wave speed (Fig. 6 B, dashed line). These two properties are well suited for experimental measurements, because they have been found to be remarkably constant in cells not perturbed by IP3 buffer (44–46).

FIGURE 6.

Slowing of the IP3 turnover with an IP3 buffer. (A) The maximal rate of [Ca2+]c rise during a [Ca2+]c spike decreases as a function of IP3 buffer concentration in the positive-feedback model (solid line), whereas it is barely affected in the negative-feedback model (dashed line). The results are shown for  (positive feedback) and

(positive feedback) and  (negative feedback); similar results are obtained for other values. (B) The intracellular wave speed decreases as a function of IP3 buffer concentration in the positive-feedback model (solid line), whereas it is barely affected in the negative-feedback model (dashed line). A solitary Ca2+ wave is initiated by a local increase in [IP3]; [Ca2+]c and [IP3] diffuse with diffusion constants of 20 and 280 μm2/s, respectively;

(negative feedback); similar results are obtained for other values. (B) The intracellular wave speed decreases as a function of IP3 buffer concentration in the positive-feedback model (solid line), whereas it is barely affected in the negative-feedback model (dashed line). A solitary Ca2+ wave is initiated by a local increase in [IP3]; [Ca2+]c and [IP3] diffuse with diffusion constants of 20 and 280 μm2/s, respectively;  (positive feedback) and 0.217 nM/s (negative feedback). (C) High IP3 buffer concentration abolishes oscillations in the positive-feedback model (

(positive feedback) and 0.217 nM/s (negative feedback). (C) High IP3 buffer concentration abolishes oscillations in the positive-feedback model ( μM,

μM,  ). (D) Oscillations persist in the presence of IP3 buffer in the negative feedback model (

). (D) Oscillations persist in the presence of IP3 buffer in the negative feedback model ( μM,

μM,  ). In all panels the IP3 buffer dissociation constant is

). In all panels the IP3 buffer dissociation constant is  μM. For the positive-feedback calculations:

μM. For the positive-feedback calculations:

s,

s,  s,

s,

/s. For the negative-feedback model

/s. For the negative-feedback model  Other parameters are as listed in Table 1.

Other parameters are as listed in Table 1.

For higher concentrations of IP3 buffer (B>20 μM), the differences between the positive- and negative-feedback models are even clearer. In the positive-feedback model, the IP3 buffer completely abolishes the [Ca2+]c oscillations, and instead a single slow [Ca2+]c transient is observed (Fig. 6 C). In the negative feedback model, the [Ca2+]c oscillations persist even for very high concentrations of IP3 buffer, although the oscillation period is increased (Fig. 6 D).

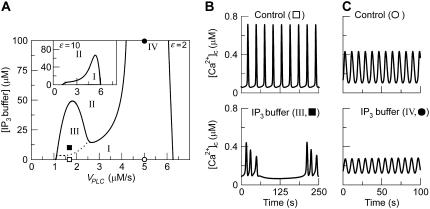

As IP3 buffering causes the strongest effects in the positive-feedback model, we have analyzed this case in more detail. Fig. 7 A summarizes the results by showing the regions of oscillatory behavior as a function of the stimulus ( ) and the concentration of exogenous IP3 buffer. Four different regions can be distinguished. In region I, the IP3 buffer slows the oscillations with respect to rise time and propagation speed (see solid lines in Fig. 6, A and B). In region II, high enough IP3 buffer concentrations abolish the oscillations (shown in Fig. 6 C). In region III, IP3 buffer can cause more complex oscillations, such as the bursting oscillations shown in Fig. 7 B. For a large range of stimuli, the oscillations disappear when sufficiently high amounts of IP3 buffer are added (transition into region II). However for strong stimulation, there can be an additional domain, region IV (Fig. 7 A). Here, the oscillations persist even at very high IP3 buffer concentration but have strongly diminished amplitude (Fig. 7 C). Note that in the presence of sufficiently high IP3 buffer, only fast oscillations (at high stimulation) can be retained. The long-period oscillations, which depend on Ca2+ feedback on PLC are invariably abolished by the IP3 buffer.

) and the concentration of exogenous IP3 buffer. Four different regions can be distinguished. In region I, the IP3 buffer slows the oscillations with respect to rise time and propagation speed (see solid lines in Fig. 6, A and B). In region II, high enough IP3 buffer concentrations abolish the oscillations (shown in Fig. 6 C). In region III, IP3 buffer can cause more complex oscillations, such as the bursting oscillations shown in Fig. 7 B. For a large range of stimuli, the oscillations disappear when sufficiently high amounts of IP3 buffer are added (transition into region II). However for strong stimulation, there can be an additional domain, region IV (Fig. 7 A). Here, the oscillations persist even at very high IP3 buffer concentration but have strongly diminished amplitude (Fig. 7 C). Note that in the presence of sufficiently high IP3 buffer, only fast oscillations (at high stimulation) can be retained. The long-period oscillations, which depend on Ca2+ feedback on PLC are invariably abolished by the IP3 buffer.

FIGURE 7.

Complex responses to an IP3 buffer in the positive-feedback model. (A) Bifurcation diagram showing the region of oscillations as function of stimulus ( ) and IP3 buffer concentration (gray-shaded area; the solid lines indicate the locus where the steady state becomes unstable via a Hopf bifurcation). In region I, regular oscillations have a decreased rate of [Ca2+]c rise with increased [IP3 buffer] as shown in Fig. 6 A. In region II, the IP3 buffer abolishes the Ca2+ oscillations completely, as shown in Fig. 6 C. In region III, bursting [Ca2+]c oscillations are observed (the lower boundary of this region is determined by a period doubling bifurcation, dotted line). We have indicated an additional region IV, which is characterized by oscillations persisting even at high [IP3 buffer]. The parameters are as in Fig. 6, with

) and IP3 buffer concentration (gray-shaded area; the solid lines indicate the locus where the steady state becomes unstable via a Hopf bifurcation). In region I, regular oscillations have a decreased rate of [Ca2+]c rise with increased [IP3 buffer] as shown in Fig. 6 A. In region II, the IP3 buffer abolishes the Ca2+ oscillations completely, as shown in Fig. 6 C. In region III, bursting [Ca2+]c oscillations are observed (the lower boundary of this region is determined by a period doubling bifurcation, dotted line). We have indicated an additional region IV, which is characterized by oscillations persisting even at high [IP3 buffer]. The parameters are as in Fig. 6, with  When the strength of the Ca2+ plasma-membrane fluxes is increased (

When the strength of the Ca2+ plasma-membrane fluxes is increased ( ), regions III and IV disappear (inset). (B) Example of bursting oscillations observed in region III (top panel, control without IP3 buffer; bottom panel, [IP3 buffer] = 10 μM;

), regions III and IV disappear (inset). (B) Example of bursting oscillations observed in region III (top panel, control without IP3 buffer; bottom panel, [IP3 buffer] = 10 μM;  ). (C) Example of oscillations in region IV (

). (C) Example of oscillations in region IV ( ; [IP3 buffer] = 100 μM), which are characterized by high frequency and low amplitude.

; [IP3 buffer] = 100 μM), which are characterized by high frequency and low amplitude.

Whether regions III and IV exist, depends on the kinetic parameters of the Ca2+ fluxes. The inset in Fig. 7 A shows a situation where the Ca2+ fluxes across the plasma membrane were increased fivefold. Then only regions I and II remain, and sufficiently high buffering of IP3 always suppresses oscillations. Closer analysis revealed that if the system can oscillate for constant [IP3] then IP3 buffer never completely abolish the oscillations and a region IV exists (A. Politi, unpublished data).

Expression of an IP3 buffer suppresses Ca2+ oscillations

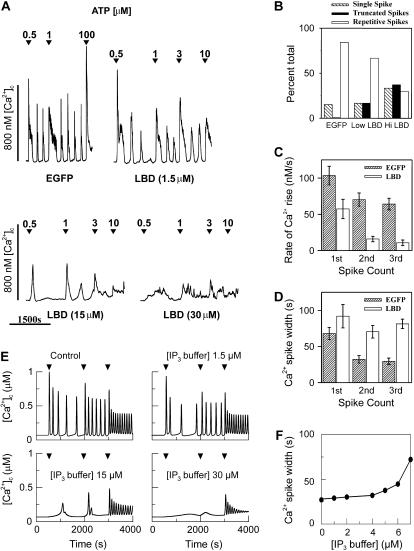

The most significant difference in the responses of the positive-feedback and negative-feedback models to the IP3 buffer is that agonist-induced oscillations always persist in the latter model whereas they can be abolished in the former. To examine the model predictions experimentally, we took advantage of a molecular IP3 buffer developed in our laboratory, which consists of the N-terminal ligand binding domain of rat type 1 IP3R linked to enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP-LBD; (47); L. Gaspers, P. Burnett, J. Johnston, A. Politi, T. Höfer, S. Joseph and A. Thomas, unpublished data). CHO cells were transiently transfected with EGFP or EGFP-LBD then challenged with submaximal and maximal ATP concentrations. The subsequent [Ca2+]c responses were monitored via changes in the fura-2 fluorescence ratio. EGFP fluorescence was utilized to distinguish transfected from nontransfected cells in a given field of view and to estimate the intracellular concentration of the transgene (see Materials and Methods).

The addition of low ATP concentrations elicited periodic [Ca2+]c spikes in >85% of the CHO cells expressing EGFP (Fig. 8, A and B) or nonexpressing cells from cultures transfected with EGFP-LBD (not shown). Agonist-evoked [Ca2+]c oscillations required functional ER Ca2+ stores (i.e., they were thapsigargin-sensitive), but ceased abruptly upon removing extracellular Ca2+ suggesting that plasma membrane Ca2+ fluxes are relatively strong in this cell type (not shown). In both GFP-expressing and nonexpressing cells, the [Ca2+]c increase immediately after agonist challenge was more prolonged and the rate of Ca2+ rise faster than subsequent [Ca2+]c oscillations (Fig. 8, A and C). No systematic differences were evident in agonist sensitivity or the pattern of the [Ca2+]c spiking between EGFP expressing and nonexpressing cells suggesting that neither EGFP nor the transfection reagents per se had significant effects on Ca2+ signaling. By contrast, the presence of EGFP-LBD had a dose-dependent effect on the agonist-dependent Ca2+ oscillations in CHO cells (Fig. 8 A). High levels of EGFP-LBD expression correlated with a loss of repetitive [Ca2+]c spiking and the appearance of low amplitude [Ca2+]c increases (Fig. 8, A and B). Moreover, EGFP-LBD expression significantly slowed the rate of [Ca2+]c rise (Fig. 8 C; p < 0.01) and significantly broadened the width of the [Ca2+]c spike (Fig. 8 D; p < 0.05) compared to EGFP expressing cells. For these data, we only analyzed EGFP-LBD expressing cells where low ATP challenge (0.5 or 1 μM) evoked at least three sequential baseline-separated Ca2+ spikes. This was observed predominately in cells expressing low levels of EGFP-LBD and, thus we probably underestimated the actions of IP3 buffering on the kinetics of [Ca2+]c oscillations.

FIGURE 8.

The effects of a molecular IP3 buffer on ATP-evoked [Ca2+]i oscillations in CHO cells. CHO cells (n = 5 independent cultures) were transiently transfected with pEGFP-LBD (EGFP-LBD) or pEGFP-C1 (EGFP). The cells were loaded with fura-2/AM 16–48 h posttransfection and challenged with the indicated ATP concentrations. The traces (A) show typical ATP-evoked [Ca2+]c spikes in CHO cells transiently expressing EGFP or different levels of EGFP-LBD. The intracellular EGFP-LBD concentration was estimated as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Data show the effects of increasing EGFP-LBD expression on ATP-evoked Ca2+signals. CHO cells expressing EGFP-LBD were arbitrarily divided into low (489 ± 66 units; n = 18 cells) or high (3170 ± 480 units; n = 27 cells) categories using a cutoff of 1000 fluorescence intensity units. The estimated mean EGFP-LBD concentration was 6 ± 0.8 or 38 ± 6 μM, respectively. The mean EGFP fluorescence intensity was 7400 ± 615 units (89 ± 7 μM; n = 198 cells). Truncated spikes are defined as low amplitude [Ca2+]c oscillations similar to those shown in the bottom traces of panel A. The initial rates of [Ca2+]c rise (C) and the widths of the [Ca2+]i spike (D) were calculated in cells expressing EGFP (n = 52 cells) or EGFP-LBD (n = 20 cells) where ATP challenge (0.5 or 1 μM) evoked at least three sequential baseline-separated Ca2+ spikes. The width of the [Ca2+]c spike were determined at half-peak height. (E) The positive feedback model, Ca2+ activation of PLC, with different IP3 buffer concentrations (as indicated) shows a good agreement with the EGFP-LBD experimental data shown in panel A. An increase in ATP is simulated by an increase in the maximal activity of PLC (arrowheads). (F) In the positive feedback model we also observe a significant increase in spike width (calculated at half-peak height). To match the Ca2+ oscillations in CHO cells all variables have been slowed by a factor 10, reference parameter set as in Fig. 6  In panel E,

In panel E,  0.2, 0.4 μM/s. Initial condition at

0.2, 0.4 μM/s. Initial condition at  In panel F,

In panel F,

According to the theoretical results, the disappearance of the oscillations and a slowing of the Ca2+ rise suggests that IP3 oscillations driven by positive feedback of Ca2+ on IP3 production are involved in this system. We have simulated the positive-feedback model with relatively strong plasma-membrane Ca2+ fluxes as observed in CHO cells. At high concentrations of IP3 buffer (Fig. 8 E), the model exhibits single transients (for lower agonist dose), and repetitive truncated spikes (for high agonist dose). Both responses closely resemble the experimentally observed patterns in cells expressing high amounts of EGFP-LBD. The Ca2+ oscillations at lower concentrations of IP3 buffer (Fig. 8 F) exhibit a broadening of the individual spikes, which is very similar to the experimental observation in cells expressing low amounts of EGFP-LBD. Also the observed decrease of the rate of Ca2+ rise is reproduced by the model (data similar to Fig. 6 A). A model with negative feedback could account for none of the experimental findings (see Fig. 6).

DISCUSSION

There has been increasing evidence that hormone-evoked periodic Ca2+ spiking can be accompanied by oscillations of the Ca2+-releasing second messenger IP3 (12–15). The experimental findings raise the questions of i), the underlying mechanisms of IP3 oscillations and ii), their potential functional role. The theoretical analysis and experiments presented here provide insight into both issues.

Several processes could be involved in the generation of IP3 oscillations. Feedbacks of IP3 and the second product of the PLC reaction, diacylglycerol, on PLC and upstream agonist receptor/G-protein could produce IP3 oscillations without involvement of Ca2+ (26,48). Alternatively, feedbacks on IP3 metabolism may be mediated by Ca2+, resulting in coupled IP3-Ca2+ oscillators (27,30,32,49). In this work, we have focused on the latter type of feedback oscillators because they can naturally account for the experimental observations of i), Ca2+ oscillations at clamped IP3 concentration and ii), coupled IP3 and Ca2+ oscillations. We considered prototypical positive and negative feedbacks of Ca2+ ions on IP3 metabolism: Ca2+ activation of PLC and Ca2+ activation of IP3 3-kinase, respectively.

The incorporation of such feedbacks into a core Ca2+ oscillator model based on the regulatory properties of the IP3 receptor can greatly expand the sensitivity of signal transduction to the hormonal stimulus. The presence of either feedback increases the range of agonist concentrations where one observes Ca2+ oscillations and enhances the ability to frequency-encode the agonist dose. Thus Ca2+ feedbacks on IP3 metabolism represent a possible mechanism for the generation of robust long-period oscillations. This is likely to be an important component of frequency-modulated Ca2+ signals, because physiological responses are controlled in this lower frequency range (50,51). Thus our model points to a physiological role of IP3 oscillations.

For the positive feedback to modulate the oscillation properties, the Ca2+ sensitivity of PLC needs to be only somewhat above basal [Ca2+]c ( ). Such values are in agreement with experimental data (33). This feedback delays the onset of the Ca2+ spike, because both [IP3] and [Ca2+]c must rise to a certain level for triggering explosive opening of the IP3R. In this way, long oscillation periods arise for low levels of stimulation, whereas for strong stimuli the high IP3 level obviates the need for additional Ca2+ activation of PLC. We have here specifically assumed that Ca2+ and agonist act on the same isoform of PLC (e.g., PLCβ). However, similar results were obtained in a model variant when the isoform PLCδ is also included in the model, which is a Ca2+-sensitive but agonist-insensitive PLC isoform (results not shown).

). Such values are in agreement with experimental data (33). This feedback delays the onset of the Ca2+ spike, because both [IP3] and [Ca2+]c must rise to a certain level for triggering explosive opening of the IP3R. In this way, long oscillation periods arise for low levels of stimulation, whereas for strong stimuli the high IP3 level obviates the need for additional Ca2+ activation of PLC. We have here specifically assumed that Ca2+ and agonist act on the same isoform of PLC (e.g., PLCβ). However, similar results were obtained in a model variant when the isoform PLCδ is also included in the model, which is a Ca2+-sensitive but agonist-insensitive PLC isoform (results not shown).

Negative feedback exerts control on the Ca2+ oscillations when IP3 removal takes place predominantly via IP3K rather than by the IP3P (>60% of the removal flux at high [Ca2+]c carried by IP3K). Long oscillation periods are generated when [IP3] drops in the wake of a Ca2+ spike due to IP3K activation and subsequently recovers slowly to the level needed to activate the IP3R. We have found that this mechanism requires a finely tuned interplay between IP3 metabolism and Ca2+ fluxes. This sensitivity may explain the discrepancy to the work of Dupont and Erneux (32), who reported only small effects of IP3K on [Ca2+]c oscillation periods. In contrast, the effects of the positive feedback were found to be robust with respect to the properties of the core Ca2+ oscillator.

The different modes of action of positive and negative feedbacks are reflected by opposing requirements on the lifetime of IP3. In the case of positive feedback, IP3 turnover must be fast to support long-period oscillations, allowing for i), coincidence of Ca2+ and IP3 spikes and ii), for the rapid removal of IP3 in the wake of a spike. In the case of negative feedback, slow IP3 turnover is required for the slow recovery of IP3 levels in between spikes. In different cellular systems, either one of the IP3 feedbacks could play a significant role in controlling Ca2+ oscillations, depending primarily on the underlying turnover rate of IP3. However, they cannot be expected to act synergistically.

A critical question is the experimental identification of the mechanisms that drive IP3 oscillations. The theoretical analysis showed that slowing the IP3 turnover by means of an IP3 buffer can be used to distinguish between the two feedback mechanisms. An IP3 buffer can quench the oscillations generated by an IP3-Ca2+ oscillator based on positive feedback of Ca2+ on IP3, but not by one based on negative feedback. Our preliminary modeling results indicate that the weak response of the negative-feedback oscillator to IP3 buffering could be a general property not limited to a mechanism operating through IP3 3-kinase. We obtained very similar results with an alternative mechanism acting through PKC-dependent inactivation of the agonist receptors.

To test this theoretical prediction, we overexpressed the ligand binding domain of the type 1 IP3R in a mammalian cell line, which acts as an IP3 buffer. The observed dose-dependent suppression of Ca2+ oscillations demonstrates that the IP3 dynamics play a critical role in the oscillator mechanism. Moreover, the detailed agreement between the experimental data and the simulations of the positive-feedback model is consistent with a coupled IP3-Ca2+ oscillator based on Ca2+ activation of PLC.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

An online supplement to this article can be found by visiting BJ Online at http://www.biophysj.org.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Fang Lui for technical assistance with the CHO cell cultures, Dr. Suresh Joseph (Thomas Jefferson University) for supplying cDNA encoding type 1 LBD, and Paul Burnett for constructing the EGFP-LBD plasmid.

Support by the Boehringer Ingelheim Fonds (to A.P.), the Hepatocyte Systems Biology program of the Federal Ministry for Education and Research of German (to T.H.), and United States National Institutes of Health grants DK38422 and AA014918 (to A.P.T.) are gratefully acknowledged.

Antonio Politi and Lawrence D. Gaspers contributed equally to this work.

References