Abstract

Our studies indicate that regulatory factor for X-box (RFX) family proteins repress collagen alpha2(I) gene (COL1A2) expression (1,2). In the present investigation, we examine the mechanism(s) underlying the repression of collagen gene by RFX proteins. Two members of the RFX family, RFX1 and RFX5, associate with distinct sets of co-repressors on the collagen transcription start site in vitro. RFX5 specifically interacts with histone deacetylase 2 (HDAC2) and the mammalian transcriptional repressor (mSin3B) whereas RFX1 preferably interacts with HDAC1 and mSin3A. HDAC2 cooperates with RFX5 to down-regulate collagen promoter activity while HDAC1 enhances inhibition of collagen promoter activity by RFX1. IFN-γ promotes the recruitment of RFX5/HDAC2/mSin3B to the collagen transcription start site but decreases the occupancy by RFX1/mSin3A as manifested by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay. RFX1 binds to methylated collagen sequence with much higher affinity than unmethylated sequence, recruiting more HDAC1 and mSin3A. The DNA methyltransferase inhibitor, 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine (aza-dC), that inhibits DNA methylation, reduces RFX1/HDAC1 binding to the collagen transcription start site in ChIP assays. Finally, both RFX1 and RFX5 are acetylated in vivo. TSA stimulates the acetylation of RFX proteins and activates the collagen promoter activity. Collectively, our data strongly indicate two separate pathways for RFX proteins to repress collagen gene expression: one for RFX5/HDAC2 in IFN-γ mediated repression, the other for RFX1/HDAC1 in methylation mediated collagen silencing.

Keywords: collagen, RFX, HDAC, CIITA, IFN-γ, methylation

Introduction

Collagen, currently consisting of more than 27 members, is a large family of extracellular matrix proteins that play vital structural and physiological roles maintaining the integrity and contributing to homeostasis of the human body (3). Due to their diverse structures and distributions as well as complex interactions with other components of the extracellular matrix, expression and regulation of collagen proteins is an extremely complicated, yet critical process, which occurs at multiple levels-transcriptional, post-transcriptional, translational, and post-translational. Type I collagen, composed of two α1(I) (COL1A1) chains and one α2(I) (COL1A2) chain, is the most abundantly expressed member of the collagen genes, thereby playing a significant role in maintaining homeostasis. The transcription of these genes is important during development and repair of injury.

Transcription of eukaryotic genes is controlled by coordination of large complexes composed of activators/co-activators or repressors/co-repressors, which function to alter histone-DNA structure in highly-ordered chromatin. Histones are subjected to a number of posttranslational modifications such as phosphorylation (4-7), acetylation (8-10), and methylation (11-14). These modifications, termed ‘histone code’, greatly impact the chromatin structure, which in turn, leads to permissive or unfavorable access of transcription factors to a particular promoter causing the differential transcriptional activity of that promoter (12,15). For example, high levels of acetylation on certain lysines on the tail of histones H3 and H4 is often associated with loose chromatin structure, favorable binding of activators/co-activators and high rate of transcription, whereas low level of acetylation is usually accompanied by compact chromatin structure, denial of access of activators/co-activators to promoters, and low rate of transcription (16-19). It is not only the intensity of acetylation/deacetylation, but also the specific sites becoming acetylated or deacetylated that dictate the overall transcriptional outcome.

Acetylation of histones is a dynamic and reversible process which is catalyzed by two groups of antagonistic enzymes called histone acetyl transferase (HAT) and histone deacetylase (HDAC). So far, eighteen different HDACs have been identified and categorized into 3 groups based on their homology to three yeast HDACs. Class I HDACs, containing HDAC1, -2, -3, and -8, are homologous to yeast yRPD3 and are expressed in most tissues (20-25). Class II HDACs, which share homology with yeast yHDA1, consist of HDAC4, -5, -6, -7, -9, and -10, and show tissue-specific expression patterns (26-30). HDAC11 has homology to both class I and II. Both class I and class II HDACs are sensitive to such inhibitors as trichastatin A (TSA) and sodium butyrate. Class III HDACs are mammalian homologs to yeast SIR2 protein which have distinct catalytic domains compared to both Class I and II HDACs and are dependent on NAD for enzymatic activity (31,32). Class III HDACs are insensitive to TSA treatment; instead, their activity can be inhibited by nicotinamide (NAM). Class I HDACs are invariably found in multi-molecular complexes containing other repressor/co-repressor proteins. For example, the NuRD complex is composed of HDAC1, HDAC2 as well as methyl group binding protein (MBP) (33,34). Another commonly found HDAC-containing complex is the Sin3 complex which consists of HDAC1 and HDAC2 in addition to Sin3-associated polypeptides-SAP18 and SAP30 (35-37).

The major focus of research of this laboratory has been toward understanding the transcriptional events occurring at the transcription start site of type I collagen genes. Earlier investigations have led to the discovery of a binding site for regulatory factor for Xbox (RFX) at the transcription start site of both α1(I) and α2(I) genes, COL1A1 and COL1A2 (38,39). Binding of two members of RFX proteins, RFX1 and RFX5, to the start sites of the type I collagen genes represses their expression. RFX1 is able to form dimers with itself as well as with two other RFX members, RFX2 and RFX3, with which RFX1 shares significant homology including the dimerization domain that mediates the complex formation. On the other hand, RFX5 lacking the dimerization domain, is less homologous to other family members, and forms a trimeric complex with two other proteins, RFXB and RFXAP(1). RFX5 is also responsible for recruiting class II transactivator (CIITA), the master regulator for major histocompatibility II (MHC II) expression, to the collagen transcription start site during IFN-γ response (2). Though both RFX1 and RFX5 down-regulate collagen expression, their distinct association with other transcription factors suggests that they are involved in different physiological and pathophysiological events leading to the repression of collagen synthesis.

Our results presented here demonstrate that RFX1 and RFX5 differentially interact with class I HDACs, underlying the different pathways when repressing collagen synthesis.

Methods

Cell culture maintenance and treatment protocols

Human lung fibroblasts, IMR-90, (IMR, NJ), human kidney cells 293FT (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and human fibrosarcoma cells, HT1080 (ATCC, MD) were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Hyclone) and 1% penicillin G-streptomycin.

In several studies IMR-90 cells were treated with IFN-γ and/or TSA (Sigma, MO). IMR-90 fibroblasts were plated in p150 tissue culture dishes at 4×106 cells/dish and maintained in DMEM with 10% FBS for 16-24 hours. Cells were pretreated in DMEM with 0.4% FBS for 16 hours prior to IFN-γ treatment (100 U/ml in 0.4% DMEM for 0, 8, 16, or 24 hours) and/or TSA treatment (0.5-2μM for 24 hours where applicable). IFN-γ and TSA was added together.

In other studies, HT1080 cells were plated at a density of 5×105 cells per P35 mm plate and treated with 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine (aza-dC) (500nM and 1μM) for 3 days in DMEM medium adding fresh aza-dC each day. In some studies HT1080 cells were treated with TSA (300 nM) for 24 hours.

DNA-affinity pull-down assay

The collagen sequence (COL1A2 −25/+30, Genbank accession number AF004877) with a HindIII overhang was synthesized as complementary strands and annealed as previously described (40). Double-stranded collagen DNA was biotin-labeled by incubating with klenow fragment (NE Biolabs, Beverly, MA) and biotin-14-dATP (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with regular dCTP, dTTP and dGTP at room temperature for 30 minutes. The reaction mixture was phenol-chloroform extracted and alcohol precipitated to remove unincorporated biotin.

Nuclear protein extracts from IMR-90 cells were obtained as previously described using 450 mM sodium chloride (1,41). The streptavidin beads (Promega, Madison, WI) were washed three times with ice-cold PBS supplemented with 1mM PMSF. Nuclear proteins (100-200 μg) were pre-cleared by incubating with the washed beads for 30 minutes at 4 °C on a shaking platform as described previously(2). Pre-cleared nuclear proteins were prepared by capturing the beads on a magnetic stand and removing the supernatant. The supernatant was then incubated with biotin-labeled collagen DNA probe (−25/+30) for 1 hour at room temperature in binding buffer (60 mM NaCl, 20mM HEPES pH7.9, 0.1mM EDTA, 4% glycerol, 2mM DTT) supplemented with BSA, poly-dIdC and sonicated salmon sperm DNA to remove non-specific binding. DNA-protein complex formed was captured by the magnetic beads, washed extensively with binding buffer supplemented with 0.01% Triton X and 100mM KCl. The bound proteins were eluted with 1X electrophoresis sample buffer by incubating at 90°C for 10 minutes and analyzed by SDS-PAGE gels.

Plasmids, transfections and luciferase assays

The COL1A2-luciferase construct (pH20) (42) contains sequences from −221 to +54 bp of mouse COL1A2 promoter fused to the luciferase reporter gene. Full-length class I HDAC expression constructs (HDAC1, HDAC2, HDAC3) in pcDNA3 and silencing HDACs (43) were kindly provided by Dr. Edward Seto. Full-length Flag-RFX5 were also kindly provided by Dr. Jenny Ting. RFX1 cDNA was excised from pHISB-RFX-1 plasmids respectively and inserted into the pIRES-hrGFP-2A (Stratagene, CA) construct which has green fluorescent protein coding sequence. RFX1 plasmid was digested with Not1 and Xho1 to produce the 5 kb vector along with 3 kb fragment. The RFX1 fragment was inserted into the EcoR1/Xho1 site of the pIRES-hrGFP-2A plasmid. This bicistronic plasmid can encode the protein along with the green fluorescent protein when expressed in mammalian cell lines.

Cells were plated at the density of 3×105 cells/well in 6-well tissue culture dishes (for IMR-90 cells) or 5×106 cells per p100 tissue culture dish (for 293FT cells). Transfections were performed with Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer's protocol. Cells were harvested 48 hours post transfections and luciferase assays were performed with a luciferase reporter assay system (Promega).

Immunoprecipitations

To investigate whether factors interact in vivo, co-immunoprecipitations were performed. Whole cell lysates (IMR-90 or 293FT with transfected constructs as indicated where applicable) were obtained by resuspending cell pellets in RIPA buffer (50mM Tris pH7.4, 150mM NaCl, 1%Triton X-100) with freshly added protease inhibitor (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) and PMSF (100μg/ml RIPA). Anti-RFX5 (194, Rockland), or anti-RFX1 (I-19, Santa Cruz) antibody was added to and incubated with IMR-90 cell lysate overnight before being absorbed by Protein A/G-plus Agarose beads (Santa Cruz). Precipitated immune complex was released by boiling with 1X SDS electrophoresis sample buffer. Alternatively, Flag-conjugated beads (M2, Sigma) were added to and incubated with 293FT cell lysate overnight. Precipitated immune complex was eluted with 3X Flag peptide (Sigma).

Westerns

Proteins were separated by 8% or 10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis with prestained markers (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) for estimating molecular weight and efficiency of transfer to blots. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) in a Mini-Trans-Blot Cell (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The membranes were blocked with 5% milk powder in Tris buffered saline (TBST) (0.05% Tween 20, 150 mM NaCl, 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4) buffer at 4°C overnight and incubated for three hours to monoclonal anti-Flag (1:1000) (Sigma), polyclonal anti-RFX5 (194, 1:1000) (Rockland), polyclonal anti-mSin3A (K-20, 1:200) (Santa Cruz), polyclonal anti-mSin3B (AK-12, 1:200) (Santa Cruz), anti-HDAC1 (H-51, 1:200) (Santa Cruz), polyclonal anti-HDAC2 (C-19, 1:200) (Santa Cruz), polyclonal anti-HDAC3 (H-99, 1:200) (Santa Cruz) polyclonal Nacetyl-lysine (1:2000)(Cell Signaling) and polyclonal anti-RFX1 (I-19, 1:100) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibodies at room temperature. After 3 washes with TBST, the membranes were incubated with appropriate secondary antibodies, either anti-goat IgG (Sigma, St.Louis, MO), anti-mouse IgG, or anti-rabbit IgG (Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) conjugated to hourseradish peroxidase, for another 1hour at room temperature. Then protein blots were visualized using ECL reagent (NEN, Boston, MA) on a Kodak image station (NEN, Boston, MA).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

Chromatin in control and IFN-γ treated cells were crosslinked with 1% formaldehyde for 8 min at room temperature, sequentially washed with PBS, Solution I (10mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 10mM EDTA, 0.5mM EGTA, 0.75% Triton X-100), and Solution II (10mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 200mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 0.5mM EGTA). Cells were incubated in lysis buffer (150mM NaCl, 25mM Tris pH 7.5, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% deoxycholate) supplemented with protease inhibitor tablet (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) and PMSF. DNA was fragmented into ∼500bp pieces using a Branson 250 sonicator. Aliquots of lysates containing 200 μg of protein were used for each immunoprecipitation reaction with anti-RFX5 (194, Rockland), anti-RFX1 (I-19, Santa Cruz), anti-mSin3A (K-20, Santa Cruz), anti-mSin3B (AK-12, Santa Cruz), anti-HDAC1 (H-51, Santa Cruz), anti-HDAC2 (C-19, Santa Cruz), and anti-HDAC3 (H-99, Santa Cruz) antibodies followed by adsorption to Protein A/G plus agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Precipitated DNA-protein complexes were washed sequentially with RIPA buffer (50mM Tris, pH8.0, 150mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% deoxycholate, 1% NP-40, 1mM EDTA), high salt buffer (50mM Tris, pH8.0, 500mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% deoxycholate, 1% NP-40, 1mM EDTA), LiCl buffer (50mM Tris, pH8.0, 250mM LiCl, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% deoxycholate, 1% NP-40, 1mM EDTA), and TE buffer (10mM Tris, 1mM EDTA pH 8.0), respectively. DNA-protein crosslink was reversed by heating the samples to 65°C overnight. Proteins were digested with Proteinase K (Sigma, Saint Louis, MO) and DNA was phenol-chloroform extracted and precipitated by 100% ethanol. Dried DNA was dissolved in 50 μl deionized distilled water and 10 μl was used for each real-time PCR reaction. The primers surrounding the collagen start site for real time PCR have been described previously (1).

RNA isolation and real-time PCR:

Cells were harvested and RNA was extracted using an RNeasy RNA isolation kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to manufacturer's protocol. Reverse transcriptase reactions were performed using a SuperScript First-strand synthesis system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to manufacturer's protocol. Real-time PCR reactions were performed on a ABI Prism 7700 sequence detection PCR machine (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) according to manufacturer's protocol. The oligonucleotide forward and reverse PCR primers, and fluorescent probes are described in table 1.

Table I.

Primers for mRNA and hnRNA real-time PCR

| Gene | Amplicon Location | Exon | Sequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| COL1A2 mRNA* | 7568-7650/8929-8965 | ||

| Forward primer | Exon 5 | 5′-GCCCCCCAGGCAGAGA-3′ | |

| Taqman probe | Exon 5/6 | 6FAM-CCTGGTCTCGGTGGGAACTTTGCTG-TAMRA | |

| Reverse primer | Exon 6 | 5′-CCAACTCCTTTTCCATCATACTGA-3′ | |

| COL1A2 hnRNA* | 2468-2552 | ||

| Forward primer | Exon1 | 5′- CTTGCAGTAACCTTATGCCTAGCA -3′ | |

| Taqman probe | Exon1/Intron1 | 6FAM- CATGCCAATGTAAGTGCCTTCAGCTTGTT -TAMRA | |

| Reverse primer | Intron1 | 5′- CCCATCTAACCTCTCTACCCAGTCT -3′ |

Genbank assession number:AF004877

Results

RFX1 and RFX5 differentially interact with Class I HDACs on COL1A2 transcription start site

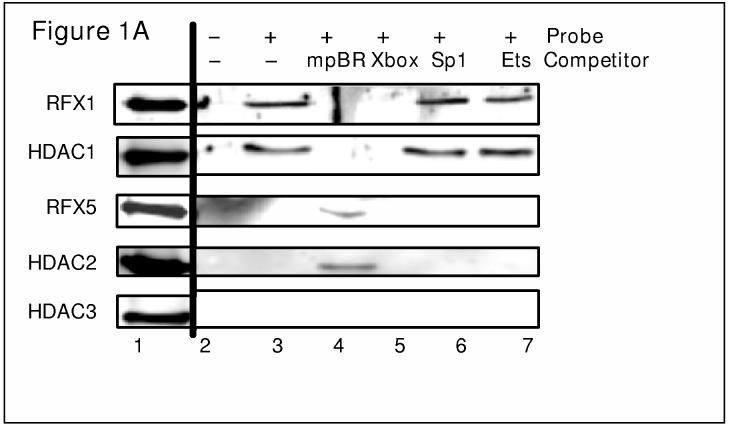

Previously, we reported that two members of the RFX family, RFX1 and RFX5, bind to the transcription start site of COL1A2 gene and repress its expression (39). During IFN-γ treatment, when RFX5 occupies the COL1A2 transcription start site, there is a coordinate decrease in acetylation of histones (1). Since transcriptional repression is usually associated with the recruitment of HDACs, we examined whether RFX1 and/or RFX5 is responsible for recruiting the HDACs to the collagen site. To this end, DNA affinity pulldown experiments were performed, as described previously(2), with nuclear proteins extracted from human IMR-90 cells and a biotin-labeled double-stranded DNA probe that spans from −25 to +30 of the collagen promoter containing the RFX binding site. Different DNA oligos were also used as competitors for RFX binding to test the specificity of the interactions. Streptavidin conjugated magnetic beads were used to sequester the biotinylated probe with bound nuclear proteins.

After extensive washing, bound proteins were eluted with SDS electrophoresis buffer, separated on SDS 10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to membranes for Western analysis using specific antibodies for RFX and HDAC family members. No proteins were present in the eluates without a DNA probe (Figure 1A, lane 2 & 1B, lane 3). In the presence of DNA probe, RFX1 is detected in the eluates along with HDAC1 (Figure 1A, lane 3 & 1B lane 4). When a methylated sequence, that acts as a competitor specifically eliminating the binding of RFX1 (mpBR) is added as previously demonstrated (40), HDAC1 binding is also lost (Figure 1A, lane 4 & 1B lane 5). This indicates that RFX1 selectively interacts with HDAC1 on the collagen start site.

Figure 1.

RFX1 interacts with HDAC1 whereas RFX5 interacts with HDAC2 at COL1A2 transcription start site in vitro. (A) DNA affinity pull-down assays were performed with IMR-90 nuclear extract as described in Materials and Methods. Eluates were separated by 10% SDS gel and Westerns performed with anti-RFX1, HDAC1, RFX5, HDAC2, or HDAC3 antibody as indicated. The original lysate (10%) was separated and labeled input. (B) IFN-γ increases the interaction between RFX5 and co-repressor molecules on COL1A2 promoter in vitro. DNA affinity pull-down assays were performed with IMR-90 nuclear extract treated with (+) or without (−) IFN-γ (100U/ml) as described in Materials and Methods. Eluates were separated by 10% SDS gel and Westerns performed with anti-RFX1, HDAC1, RFX5, HDAC2, mSin3B, or HDAC3 antibody as indicated.

In contrast, RFX5 is able to bind to DNA in the absence of RFX1 along with HDAC2 (Figure 1A, lane 4 & 1B, lane 5), suggesting a selective interaction between RFX5 and HDAC2. The MHC II X-box sequence abolishes the binding of RFX1 (Figure 1A, lane5) and RFX5 (Figure 1B, lane 6), as well as the two HDACs whereas neither Sp1 nor Ets consensus sequence alters the binding of RFX1, HDAC1, RFX5 or HDAC2, implying that the interactions are specific. A third class I HDAC, HDAC3, is not detectable under any of these circumstances probably because it is not recruited to the collagen transcription start site through RFX proteins.

IFN-γ enhances the interaction between RFX5 and co-repressors

Earlier studies indicated that IFN-γ increased RFX5 protein levels, nuclear localization, and occupation on collagen start site in IMR-90 cells (1). Since there was an interaction between RFX5 and HDACs, RFX5 may recruit more HDACs and IFN-γ could enhance the association between RFX5 and HDACs at the collagen transcription start site. Increased HDACs could inhibit histone acetylation, and ultimately repress collagen transcription. To test this hypothesis, DNA affinity pull-down experiments were performed first with nuclear proteins extracted from IMR-90 cells treated with or without IFN-γ (100 U) for 24 hours.

Both RFX1 and HDAC1 bind to the collagen sequence with similar affinity either with or without IFN-γ treatment (compare lane 4 and lane 10). With the addition of methylated mpBR, binding of RFX1 as well as HDAC1 is eliminated whereas RFX5, HDAC2, and mSin3B associate with the probe (lane 5). Binding of RFX5, HDAC2, and mSin3B are all enhanced with IFN-γ treatment (compare lane 5 to lane 11). The specificity of the interactions were maintained in the presence of IFN-γ (lanes 12-14), suggesting that more co-repressors are recruited to the collagen transcription start site by RFX5.

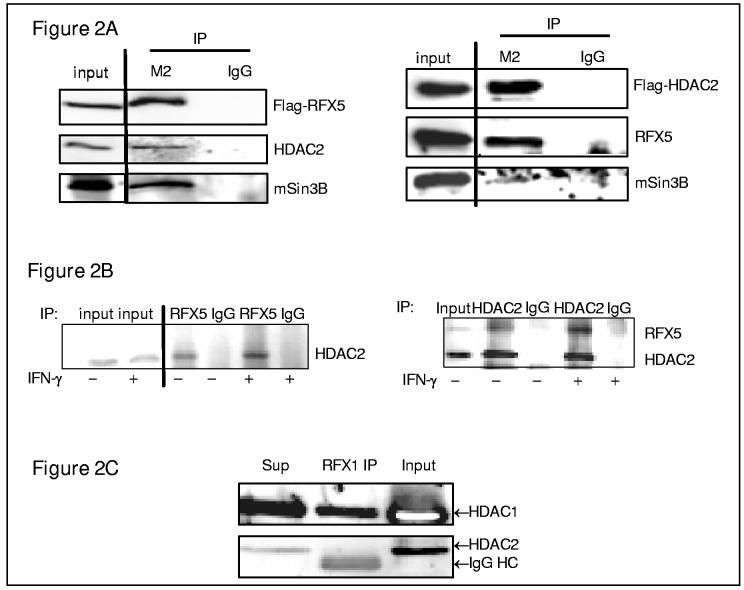

Interactions between RFX proteins and HDACs are DNA-independent

Next, co-immunoprecipitation experiments were performed between RFX proteins and HDACs to determine whether interactions depend on DNA. The first immunoprecipitation experiments were performed using epitope tagged RFX5 and HDAC expressed proteins in 293FT cells because they are fast-growing human kidney cells that stably expresses the large T antigen of SV40 allowing increased amounts of over expressed protein. Flag-conjugated beads were used to precipitate protein extracts from 293FT cells transfected with either Flag-tagged RFX5 or HDAC2. Eluates were separated by SDS-PAGE gels and examined for endogenous proteins that might co-precipitate with Flag-tagged proteins. As depicted in Figure 2A, Flag-RFX5 co-precipitates with endogenous HDAC2 (left panel) and vice versa (right panel), indicative of a reciprocal interaction. In both cases, mSin3B is present in the immune complex.

Figure 2.

RFX proteins interact with HDACs independent of DNA. (A) RFX5, HDAC2 and mSin3B interact with each other reciprocally. 293FT cell extracts (500 μg) with transfected Flag-RFX5 (left panel) or Flag-HDAC2 (right panel) were precipitated using Flag-conjugated beads (40 μl) (M2) or pre-immune IgG-conjugated beads (40 μl) (IgG) as described in Materials and Methods. Eluates were separated by 10% SDS gel and Westerns performed with anti-Flag, RFX5, HDAC2, or mSin3B antibody as indicated. 10% of the original lysate was also loaded as input. (B) RFX5 interacts with HDAC2 in IMR-90 cells. Whole cell extracts (500 μg) prepared from IMR-90 cells with (+) or without (−) IFN-γ treatment were precipitated using an anti-RFX5 antibody (5 μg) (left panel), an anti HDAC2 antibody (5 μg) (right panel) or anti-pre-immune IgG (5 μg) as indicated. Eluates were separated by 10% SDS gel and Westerns performed with an anti-HDAC2 antibody (left panel) or both anti-HDAC and anti-RFX5 antibody. The original lysate proteins (10%) was also loaded and labeled as input. (C) RFX1 interacts with HDAC1 but not HDAC2 in IMR-90 cells. Nuclear extracts (300 μg) prepared from IMR-90 cells were precipitated using an anti-RFX1 antibody (5 μg). Eluates were separated by 10% SDS gel and Westerns performed withanti-HDAC1 or HDAC2 antibody as indicated. 10% of the original lysate was also loaded as input.

Next, nuclear proteins from IMR-90 cells treated with or without IFN-γ were precipitated using an anti-RFX5 or anti-HDAC2 antibody to examine endogenous interactions. Eluates were separated by SDS-PAGE gels and examined for HDAC2 (left panel) or RFX5 and HDAC2 (right panel). HDAC2 is immunoprecipitated with the RFX5 antibody but not with a pre-immune IgG (Figure 2B, right panel). More HDAC2 is co-immunoprecipitated with RFX5 antibody from IFN-γ treated cells. HDAC2 antibody also co-immunoprecipitated increased amounts of RFX5 after IFN-γ treatment (Figure 2B, right panel) suggesting increased interactions between these proteins during IFN-γ treatment.

Lastly, to examine endogenous interactions, RFX1 was immunoprecipitated from IMR-90 nuclear extracts with an anti-RFX1 antibody. Proteins in the supernatant and precipitate were separated by SDS-PAGE gels and examined for endogenous proteins that remain in the supernatant or co-precipitate. A considerable fraction of HDAC1 co-preciptiates with RFX1 (Figure 2C). In contrast to RFX5, RFX1 did not co-precipitate with HDAC2 (Figure 2C). These data suggest that RFX proteins probably associate with HDAC before recruiting them to the collagen transcription start site.

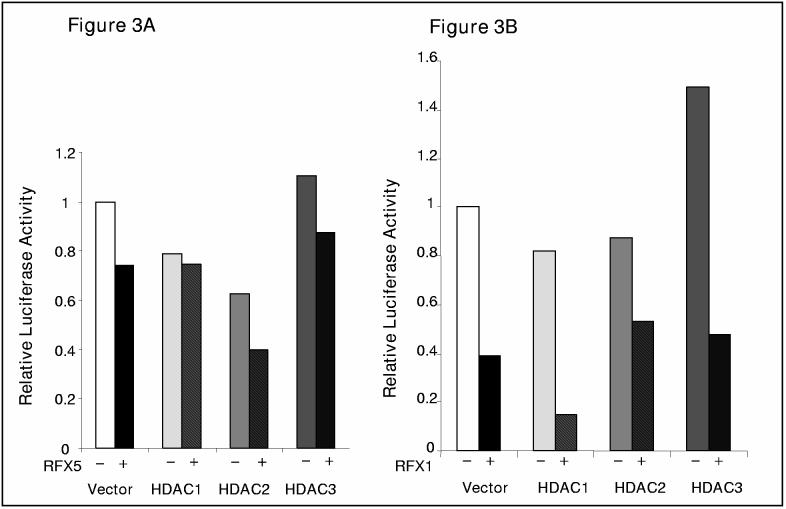

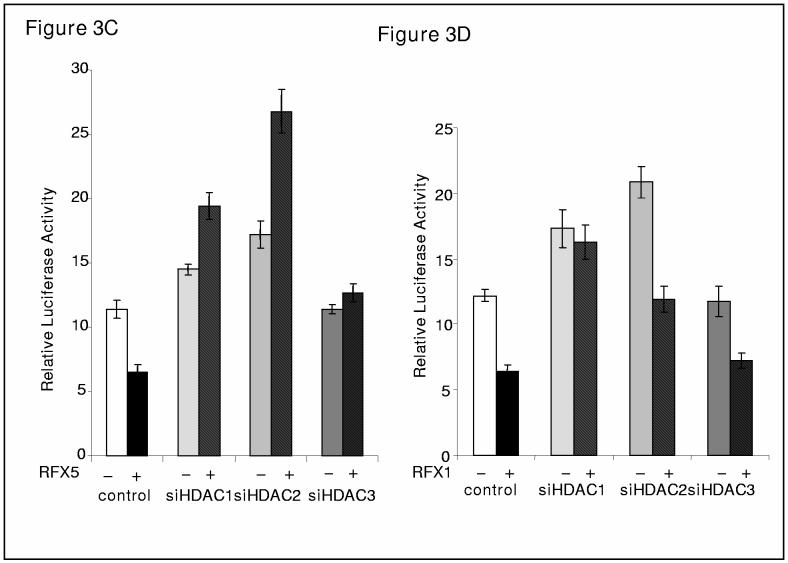

Class I HDACs display distinct functions regulating COL1A2 promoter activity

Since there were interactions between RFX proteins and HDACs, we examined whether these interactions bear any functional significance. Transient transfections were performed in IMR-90 cells with different HDAC expression constructs with or without RFX expression plasmids. As shown in Figure 3, both HDAC1 and HDAC2 repress the collagen promoter activity whereas HDAC3 does not significantly alter COL1A2 promoter activity, which is in accordance with our binding data (Figure 1). RFX5 represses better with HDAC2 (Figure 3A). Similarly, RFX1 represses better with HDAC1 (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

RFX proteins functionally interact with different HDACs on COL1A2 promoter. (A). HDAC2 enhances repression of COL1A2 promoter by RFX5. A COL1A2 promoter construct (pH20, 0.5μg) was co-transfected with different class I HDAC constructs (0.5μg) in the presence (+) or absence (−) of RFX5 (0.5μg), along with GFP (0.1μg) for normalization, into IMR-90 cells in duplicate wells as described in Materials and Methods. Average luciferase activities were normalized by both protein concentration and GFP fluorescence and were expressed as relative percentage activity compared to the control group in which an empty vector was transfected. This representative experiment was repeated at least three times. (B). HDAC1 enhances repression of COL1A2 promoter by RFX1. A COL1A2 promoter construct (pH20, 0.5μg) was co-transfected with different class I HDAC constructs (0.5μg) in the presence (+) or absence (−) of RFX5 (0.5μg), along with GFP (0.1μg) for normalization, into IMR-90 cells in duplicate wells as described in Materials and Methods. Average luciferase activities were normalized by both protein concentration and GFP fluorescence and were expressed relative percentage activity compared to the control group in which an empty vector was transfected. This representative experiment was repeated at least three times. (C, D) Silencing HDAC constructs activate COL1A2 promoter activity. A COL1A2 promoter construct (pH20, 0.5μg) was co-transfected with different class I siHDAC constructs (43) in the presence (+) or absence (−) of RFX5 (C, 0.5μg) or RFX1 (D, 0.5μg), along with GFP (0.1μg) for normalization, into IMR-90 cells in triplicate wells as described in Materials and Methods. Average luciferase activities were normalized by both protein concentration and GFP fluorescence and were expressed as relative luciferase activity per μg protein per ng GFP. This representative experiment was repeated at least twice.

Next, siHDACs (43) were transfected with or without RFX expression constructs (Figure 3C and 3D). Silencing either HDAC1 or HDAC2, but not HDAC3 activated collagen promoter activity. Surprisingly without these HDAC enzymes, RFX5 also further activated the collagen promoter (Figure 3C). RFX1 remained a repressor with siHDAC2 and siHDAC3 but lost its ability to repress collagen promoter without HDAC1. This further demonstrates the different functional interactions between the RFX family members.

RFX5/HDAC2/mSin3B are involved in IFN-γ mediated collagen transcriptional repression

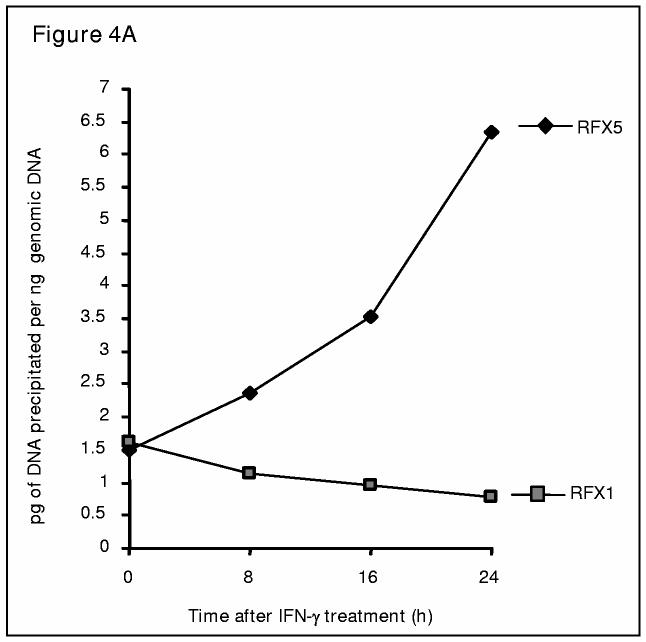

Since there is differential association between RFX proteins and HDACs, both physically and functionally, we hypothesized that RFX5/HDAC2 and RFX1/HDAC1 might be involved in different mechanisms responsible for collagen repression. Our previous reports suggest that RFX5 complex might be responsible for mediating IFN-γ repression of collagen transcription (1,2). Since certain co-repressor proteins were associated with RFX5 on the collagen start site in vitro in DNA affinity pull-down assays (Figure 1) and the association could be increased by IFN-γ (Figure 1B), it was hypothesized that these repressors might be recruited to the collagen site by RFX5 during IFN-γ response in vivo to repress collagen expression. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed with anti-RFX5, RFX1, HDAC1, HDAC2, HDAC3, mSin3A as well as mSin3B antibodies in IMR-90 cells treated with IFN-γ for 0, 8, 16 or 24 hours.

Similar amounts of genomic DNA surrounding the COL1A2 transcription start site is precipitated by either RFX5 or RFX1 antibody (Figure 4A). During IFN-γ treatment, however, binding of RFX5 to the collagen sequence is greatly enhanced whereas RFX1 binding is gradually and slightly decreased, suggesting that RFX5, but not RFX1, is involved in IFN-γ mediated collagen repression.

Figure 4.

IFN-γ induces a distinct set of repressors/co-repressors on COL1A2 transcription start site in vivo. (A). IFN-γ treatment leads to increased occupancy of RFX5 as well as decreased occupancy of RFX1 on COL1A2 transcription start site. Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays were performed with IMR-90 cells treated with IFN-γ (100U/ml) for 0, 8, 16, or 24 hours as indicated using anti-RFX1 or anti-RFX5 antibodies as described in Materials and Methods. This experiment was repeated at least twice in duplicate wells. A representative graph was shown. Data were expressed as picogram DNA precipitated by indicated antibody per nanogram total genomic DNA. (B). IFN-γ treatment leads to increased occupancy of mSin3A as well as decreased occupancy of mSin3B on COL1A2 transcription start site. Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays were performed with IMR-90 cells treated with IFN-γ (100U/ml) for 0, 8, 16, or 24 hours as indicated using anti-mSin3A or anti-mSin3B antibodies as described in Materials and Methods. This experiment was repeated three times in duplicate wells and plotted as average+/−S.D. Data were expressed as picogram DNA precipitated by indicated antibody per nanogram total genomic DNA. One-way ANOVA was used to assess the statistical significance. **, p<0.05 and ***, p<0.01 . (C). IFN-γ treatment leads to increased occupancy of HDAC2, but not HDAC1 or HDAC3, on COL1A2 transcription start site. Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays were performed with IMR-90 cells treated with IFN-γ (100U/ml) for 0, 8, 16, or 24 hours as indicated using anti-HDAC1, HDAC2 or anti-HDAC3 antibodies as described in Materials and Methods. This experiment was repeated at least twice in duplicate wells. A representative graph was shown. Data were expressed as picogram DNA precipitated by indicated antibody per nanogram total genomic DNA.

More DNA are precipitated by mSin3A binding to the collagen start site than mSin3B before IFN-γ is added (Figure 4B, compare 0 hour mSin3A to 0 hour mSin3B). However, while binding of mSin3B increases with time during IFN-γ treatment, mSin3A occupancy is continuously decreased. By 24 hours of IFN-γ treatment, mSin3A binding is decreased to the level of mSin3B binding before IFN-γ treatment whereas binding of mSin3B is stimulated to the level of mSin3A binding at the beginning of IFN-γ treatment. In other words, it appears as though IFN-γ induces an exchange of mSin3A for mSin3B on the collagen transcription start site.

Meanwhile, when the occupancy of HDACs was examined, it was discovered that HDAC2 was the predominant form of histone deacetylase present on the collagen transcription start site before IFN-γ treatment. Binding of HDAC1 and HDAC3 was minimal compared to the binding of HDAC2, although the amount of DNA precipitated by either anti-HDAC1 or anti-HDAC3 antibody was significantly above control levels (Figure 4C).

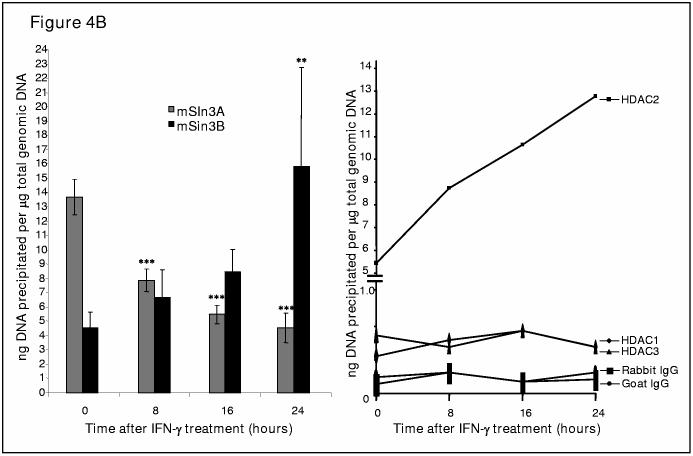

RFX1/HDAC1/mSin3A are involved in methylation mediated collagen transcriptional repression

Our recent studies indicate that collagen expression is greatly decreased when the gene is methylated (44) and that RFX1 binding to the collagen site is methylation sensitive (38,40), raising the possibility that RFX1 might be involved in methylation mediated collagen repression by recruiting co-repressors to the collagen transcription start site. To examine the validity of this hypothesis, DNA affinity pull-down experiments were performed using either a regular biotinylated COL1A2 DNA probe (−25 to +30) or the same probe that was methylated at the +7 site which enhances the binding of RFX1 to the collagen transcription start site (40). As depicted in Figure 5A, binding of RFX1 was much more robust on the methylated probe than on the unmethylated probe as expected. Interestingly, both HDAC1 and mSin3A bind to the methylated probe more strongly just like RFX1, supporting the notion that during methylation of collagen DNA more RFX1 is able to bind to the transcription start site and recruit more co-repressor complexes to repress collagen transcription. No RFX5 binding is detectable under these conditions.

Figure 5.

Methylation of the collagen gene (COL1A2) enhances the interaction between RFX1 and co-repressors. (A). Methylation enhances the binding of RFX1, HDAC1, as well as mSin3A to COL1A2 sequence in vitro. DNA affinity pull-down assays were performed with IMR-90 nuclear extract using either un-methylated probe (U) or methylated probe (M) as described in Materials and Methods. Eluates were separated by 10% SDS gel and Westerns performed with anti-RFX1, HDAC1, RFX5, or mSin3A antibody as indicated. 10% of the original lysate was also loaded as input. (B, C) Aza-dC treatment of HT1080 cells leads to decreased occupancy of RFX1 and HDAC1 on COL1A2 transcription start site. Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays were performed with HT1080 cells treated with Aza-dC at indicated concentrations for 72 consecutive hours using anti-RFX1 (B), anti-HDAC1, or anti-HDAC2 (C) antibodies as described in Materials and Methods. This experiment was repeated at least twice and a representative graph was shown. Data were expressed as picogram DNA precipitated by indicated antibody per nanogram total genomic DNA.

The inhibitor, aza-dC, a compound that inhibits DNA methyl transferases (DNMTs), dramatically (40 fold) increases collagen gene expression in a fibrosarcoma cell line, HT1080, in which 50% of collagen genomic DNA is methylated (38,44). Therefore, we examined whether the effect of aza-dC is mediated through diminished binding of RFX1 as well co-repressors to the collagen transcription start site due to demethylation. ChIP assays were performed with HT1080 cells treated with different concentrations of aza-dC for 72 hours using anti-RFX1, HDAC1, as well as HDAC2 antibodies. RFX1 binding is decreased with aza-dC treatment in a dose response manner by up to 60% (Figure 5B). Interestingly, HDAC1 binds to the partially methylated collagen transcription start site in vivo much more strongly than HDAC2 (Figure 5C). Binding of HDAC1 is also greatly decreased by aza-dC treatment similar to RFX1, further confirming that RFX1/HDAC1 might be involved in DNA-methylation mediated collagen transcriptional repression.

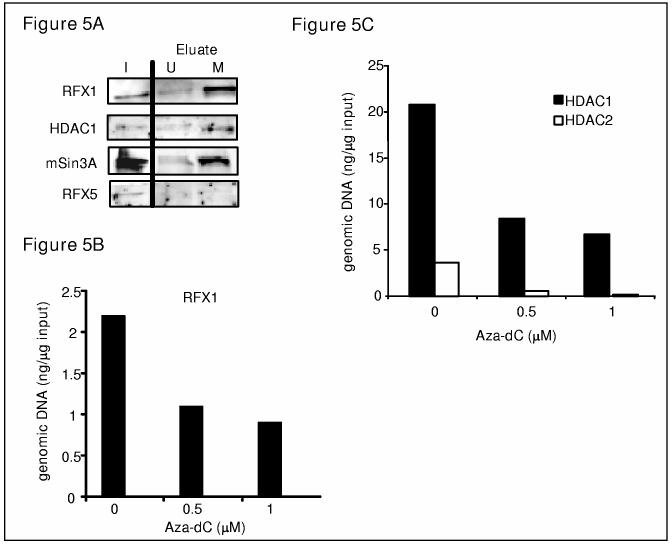

TSA has differential cell specific effects on steady state mRNA levels.

Since HDACs are clearly involved in the repression of collagen transcription, we postulated that inhibition of overall HDAC activity would increase collagen transcription. TSA is a general inhibitor for Class I and II HDACs that alters expression of many genes presumably through histone deacetylation. First, HT1080 cells were treated with several doses of TSA (50, 100, 500 1000 nM) for 24 hours. There was no change in collagen mRNA levels at low doses. At higher doses of TSA there was a 5 fold (500 nM) or 10 fold (1000 nM) increase in collagen mRNA (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

TSA stimulates COL1A2 mRNA in a cell specific manner. (A) HT1080 cells were untreated or treated with 300 nM of TSA for 24 hours before harvesting as described in Methods and Materials. Total RNAs were prepared, transcribed to form cDNA, and real time PCR reactions were performed with the cDNA samples using primers to detect COL1A2 mRNA. (B,C) IMR-90 cells were untreated or treated with IFN-γ (100 U/ml) and/or TSA (500 nM) for 24 hours before harvesting as described in Methods and Materials. Total RNAs were prepared, transcribed to form cDNA, and real time PCR reactions were performed with the cDNA samples using primers to detect COL1A2 mRNA (B) or COL1A2 hnRNA (C) (see table 1 for primers). Each experiment was repeated at least three times in duplicate wells. Data are expressed as relative RNA levels compared to control levels, normalized to 18S RNA and presented as average±S.D. (A) Paired-sample T Test, 2 tailed and (B,C) One-way ANOVA was performed to evaluate the statistical significance, *** p<0.01.

On the other hand, when IMR-90 cells were treated with TSA (500 nM) there was no significant increase in collagen mRNA levels (figure 7B). IFN-γ repressed collagen mRNA levels by 50% in 24 hours. TSA partially reversed the repression of collagen mRNA expression.

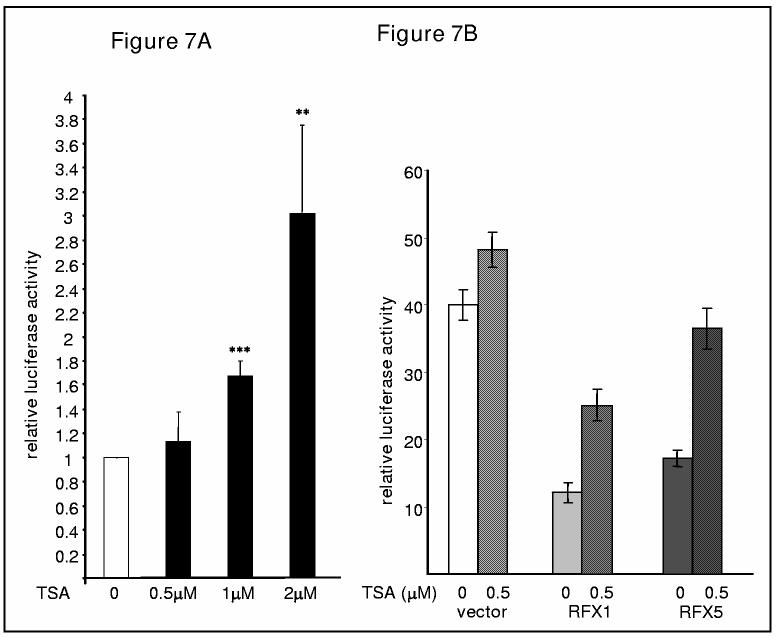

Figure 7.

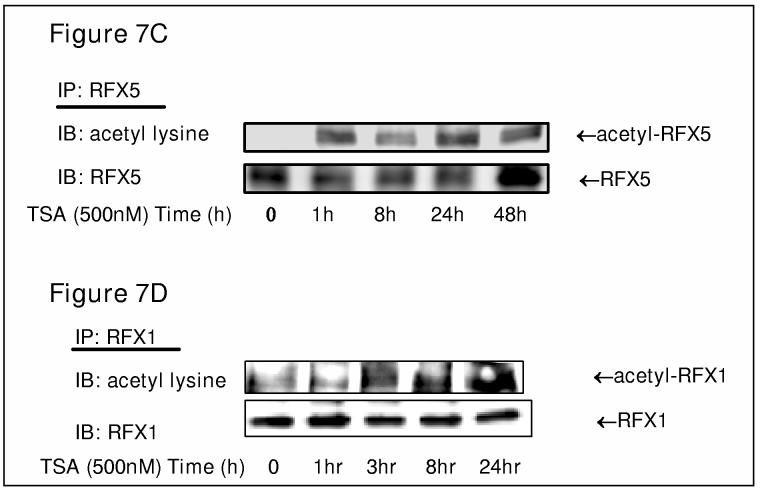

TSA stimulates COL1A2 promoter activity in a dose response manner. (A and B) A COL1A2 promoter construct (pH20, 0.5μg) was co-transfected with or without RFX expression constructs (0.5μg), along with GFP (0.1μg) for normalization, into IMR-90 cells in duplicate wells as described in Materials and Methods. 24 hours after transfections, cells were treated with TSA at indicated concentrations for additional 24 hours before harvesting. Luciferase activities were normalized by both protein concentration and GFP fluorescence and were expressed relative percentage activity compared to the control group in which an empty vector was transfected. This experiment was repeated three times and data were shown as average +/− S.D. One-way ANOVA was used to evaluate the statistical significance. **, p<0.05 and ***, p<0.01. (B, C). TSA enhances the acetylation of both RFX5 and RFX1. Whole cell extracts prepared from IMR-90 cells with TSA (500nM) treatment for indicated period of time were precipitated using an anti-RFX5 antibody or an anti-RFX1 as indicated. Eluates were separated by 10% SDS gel and Westerns performed with anti-acetyl lysine, RFX5 or RFX1 antibody as indicated.

The mRNA steady state levels are a combination of transcription and degradation or processing of mRNA. In order to examine early transcription, primers within the second intron and second exon (table 1) were used to measure heterogeneous RNA transcripts. Total RNA was DNAase treated and no reverse transcriptase was used as controls to be sure that RNA, not DNA, was measured by these primers. TSA treatment increased transcription of heterogenous collagen mRNA more than steady state mRNA in the IMR-90 cells (Figure 7C) suggesting that TSA increases transcription and degradation or processing of mRNA. IFN-γ repressed collagen heterogeneous RNA to the same extend as steady state mRNA.

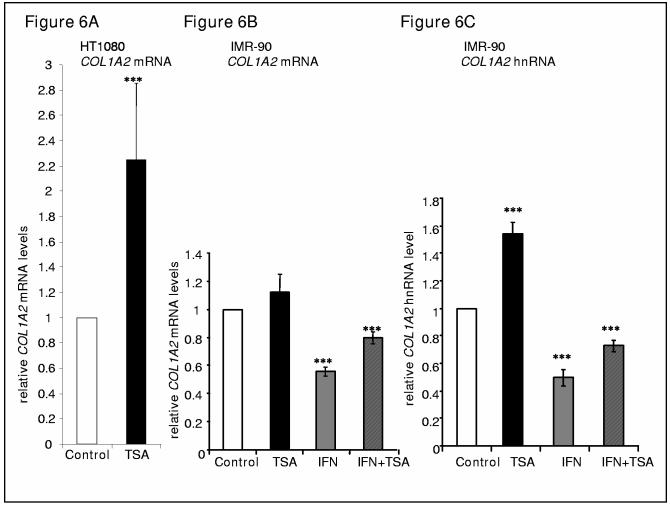

TSA stimulates collagen promoter activity and partially blocks repression by RFX proteins.

Even though TSA effects on collagen mRNA was low, TSA activated collagen promoter-luciferase activity in IMR-90 cells (Figure 8A). Over expression of RFX1 and RFX5 repressed collagen synthesis and TSA treatment was able to partially block this repression (Figure 8B). RFX5 seemed to be more sensitive to TSA than RFX1 since TSA (500 nM) almost completely blocked repression by RFX5 over expression.

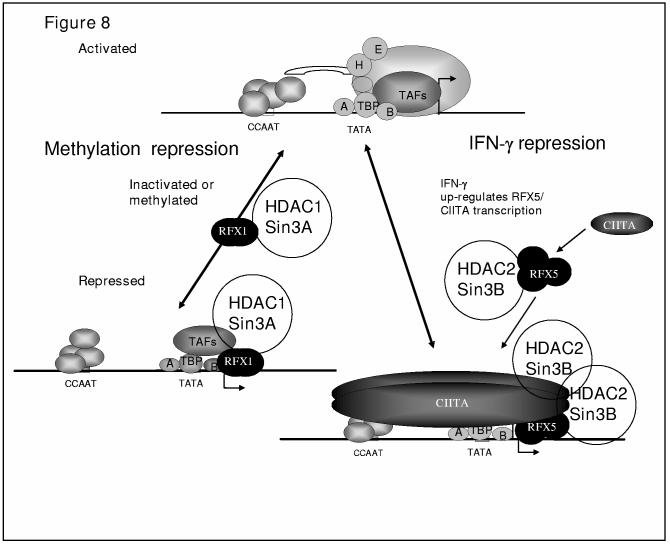

Figure 8.

Model for RFX family repression of collagen gene expression. A schematic representation illustrating two distinct pathways for collagen repression by RFX1 and RFX5. RFX1 is in a complex with HDAC1 and Sin3A. Methylation of the collagen gene at CpG +7 activates RFX1 interaction with the collagen gene bringing HDAC1 to the site. RFX5 differentially interacts with HDAC2 and Sin3B. IFN-γ treatment increases expression of RFX5 complex proteins and CIITA allowing increased interaction with HDAC2/Sin3B as well. Once the RFX5 complex is assembled, it interacts with CIITA which may also interact with HDACs. The drawing at the bottom represents some possible interactions showing proteins such as TBP, TFIIA, and TFIIB and NFY that can interact with CIITA. The collagen promoter cis-acting consensus sites are shown as boxes (TATA, TATA box or TFIID binding site, CCAAT, CBF/NF-Y binding site,(78).

RFX proteins are acetylated by TSA treatment.

Although HDACs are active on histones, several acetylated transcription factors are deacetylated by HDACs. To determine if RFX proteins are acetylated, IMR-90 cells were treated with 1μM TSA and the acetylation of either RFX5 or RFX1 was examined by immunoprecipitation followed by Western blot with a specific anti-lysine antibody. Intriguingly, both RFX5 (Figure 7C) and RFX1 (Figure 7D) are acetylated in vivo and their acetylation is dramatically stimulated by TSA treatment within 24 hours.

Discussion

Previously, we demonstrated that there is a binding site for the RFX family of transcription factors within the first exon (−1 to +20) of the COL1A2 gene (40). Two members of the RFX family, RFX5 and RFX1, bind to this site and repress collagen expression (39). RFX1 homodimers and RFX1/RFX2 heterodimers bind to the collagen gene with higher affinity especially when it is methylated on the coding strand (38-40,44,45). In this paper, it is clear that RFX1 interacts on the collagen start site with HDAC1 by DNA affinity precipitation (Figure 1). This interaction of RFX1 and HDAC1 with collagen DNA is increased when the CpG site within the RFX consensus sequence is methylated (Figure 5A). In normal fibroblasts there is a small, but measurable amount of RFX1 binding within chromatin as judged by ChIP assays (Figure 4A). Collagen type I genes are methylated in DNA from certain cancer lines and in colorectal tumors (44). The collagen gene in HT1080 cells is 50% methylated at the CpG within the RFX1 binding site (44) and aza-dC increases collagen expression as much as 40 fold in this fibrosarcoma cell line (44,46). RFX1 occupies the site 2 fold more in HT 1080 cells than in IMR-90 cells (data not shown). In HCT116 cells that have higher methylation status of the collagen gene, RFX1 occupancy is further increased (data not shown) suggesting that RFX1 does interact more with collagen start site when the gene is methylated. Aza-dC, which decreases methylation by inhibiting DNMTs, also decreases the occupancy of RFX1 as well as HDAC1 on the collagen start site (Figure 5). This data suggests again that RFX1 and HDAC1 interact at the DNA within chromatin. In fact, RFX1 also co-immunoprecipitates with HDAC1, but not HDAC2 or HDAC3, suggesting that these protein-protein interactions occur independent of RFX1-DNA interactions.

On the other hand, RFX5 interacts with two other RFX proteins, RFXB and RFXAP, as well as CIITA, to repress collagen transcription during IFN-γ stimulation (1,2). This study demonstrates that RFX5 occupies the collagen gene and RFX5 occupancy increases with IFN-γ treatment as RFX1 occupancy decreases (Figure 4A). HDAC2, but not HDAC1 or HDAC3, also increases on the collagen gene with time of IFN-γ treatment (Figure 4B) suggesting that HDAC2 is responsible for the deacetylation of histones surrounding the collagen start site observed earlier (1). Therefore, although both RFX1 and RFX5 are repressors for the COL1A2 gene, the underlying mechanisms might differ through different co-repressor interactions which could account for altered cellular responses impacting collagen expression. Two collagen-related events, namely IFN-γ regulated collagen repression during pulmonary fibrosis or inflammation, and methylation-mediated collagen down-regulation in carcinogenesis, has led to an association of these two events with the RFX family. RFX1 might be responsible for methylation whereas RFX5 may be responsible for IFN-γ mediated collagen down-regulation.

CIITA is also recruited to the collagen transcription start site by RFX5 with time of IFN-γ treatment (2). Earlier studies demonstrate that CIITA interacts with HDAC1 and mSin3A to terminate MHC II activation (47,48). However, this investigation suggests that HDAC2 and Sin3B occupy the collagen transcription start site during IFN-γ treatment (Figure 4B). Our preliminary results suggest that CIITA can complex with HDAC2 and Sin3B (data not shown). Although our effort so far has been concentrated on RFX5 and CIITA, recent evidence has been published that the other two members of the RFX5 complex, RFXB and RFXAP, are both capable of interacting with certain histone-modifying factors (49,50), suggesting a universal role for RFX5 proteins in transcriptional control. RFXAP, for example, complexes with brahma related gene 1 (BRG1), an ATPase-dependent chromatin remodeling molecule, to regulate MHC II expression (49). RFXANK is a binding partner for HDAC4 although the biological significance of this interaction remains unclear (50). Therefore, there might be extensive interactions between histone modifying proteins and RFX-associated transcription factors. This may explain why silencing of any one of the class I HDACs still caused an increase in collagen promoter activity. Certainly other classes of HDACs, such as HDAC4 discussed above, could be involved in collagen repression through the RFX complex.

Co-repressor complexes have been isolated containing several HDACs with HDAC1 and HDAC2 usually isolated together with Sin3A (36,37). However, recently interactions of HDACs with individual transcription factors have been noted especially in the Sp1/kruppel zinc finger family(51-54). HDACs interact with Sp1 protein without activation of the enzyme activity by blocking access of the Sp1 protein to the DNA (53). Collagen is a Sp1 activated promoter and, therefore, the recruitment of HDAC to the collagen gene may block assess to Sp1 sites in the promoter. In this case, HDAC represses transcription with out active catalytic activity.

TSA inhibits multiple histone deacetylases in class I and class II causing wide ranging changes in gene expression. The effects of TSA on collagen gene expression are dependent on cell type. In our studies, TSA activated gene expression in the cancer cell line, HT1080. Gene expression of collagen in human hepatoma cells is induced by TSA accompanied by changes in histone acetylation (55). However, one of the cell lines, PLC/PRF, had no detectible collagen expression. Our investigations on this cell line indicate that the collagen gene is very highly methylated and TSA, therefore, can not activate a gene silenced by complete methylation. On the other hand, TSA can induce collagen gene expression in a variety of cancer cell lines with partially methylated collagen genes such as breast cancer cell line, MCF7, or colorectal cancer cell line, HCT116 (Unpublished results).

Our studies also indicate that in fibroblasts, TSA produces no significant changes in steady state mRNA levels. However, this seems to be caused by a combination of increased transcription with accompanying increases in degradation and/or processing. Others have demonstrated that TSA suppresses collagen synthesis in dermal fibroblasts and hepatic stellate cells (56-58). Although steady state mRNA and protein levels of collagen decrease after TSA treatment, nuclear run on studies indicated that transcription of type I collagen actually was activated supporting our results with hnRNA(58). The decrease in collagen found by these investigators is most likely due to indirect mechanisms involving increased degradation or processing of collagen mRNA and protein due to multiple changes in gene expression from TSA inhibition of HDACs.

The actual increased acetylation of RFX1 and RFX5 proteins with TSA treatment suggests that the mechanism for repression of collagen through the RFX family may require active deacetylation activity of HDAC. The role of acetylation of RFX family needs to be further analyzed. Protein acetylation of transcription factors has been implicated in multiple cellular processes including differentiation, metabolism, proliferation, and survival against stress (59-62). NF-κB, c-Myc, Sp3, p53, FOXO, GATA and SMAD7 have all been identified as targets for acetylation (61,63-66). For example, acetylation of SMAD 7 is involved with stabilizing the protein (67). On the other hand, acetylation of p53 is required for efficient recruitment of co-activators to promoter regions as well as activation of target genes (68-70). Transcriptional output mediated by FOXO is controlled via a two-tiered mechanism of phosphorylation and acetylation (71). FOXO and RFX family have similar winged helix DNA binding domains (72) so they could be regulated in a similar manner by acetylation. The acetylation may alter the interaction of RFX1 with co-repressors or with DNA. The overall consequence of acetylation is not well understood and seems to vary from one factor to another and depend on specific circumstances.

The roles of HDACs in several diseases, especially in lung inflammation (73,74) and in cancer (75), have been recently outlined. HDAC2 specifically may decrease in COPD patients causing corticosteroid resistance (74,76). HDAC1 has been associated with certain types of breast cancer (77). These studies point out the biological significance of acetylation and deacetylation and the need to investigate the mechanism of action on individual genes associated with these diseases.

In summary, the RFX family represses collagen transcription at the transcription start site through either methylation specific binding by RFX1-3 family members or through IFN-γ stimulated binding during inflammation by RFX5/CIITA complex (Figure 8). In each case, a specific co-repressor complex most likely contains RFX family members. RFX1 interacts best with HDAC1 and mSin3A whereas RFX5/CIITA interacts with HDAC2 and mSin3B on the collagen transcription start site. During IFN-γ treatment, RFX5 synthesis, translocation to the nucleus, and complex formation is increased (1). CIITA is expressed and recruited to the collagen start site with RFX5(2). Most likely RFX5 becomes deacetylated by HDAC2 which increases complex interactions and repressor activity of RFX5. If the collagen gene is methylated, RFX1 interacts with the collagen gene and represses transcription through HDAC1 deacetylation of chromatin. This paper reveals that different members of the same family of transcription factors repress collagen transcription through similar but distinct mechanisms.

Acknowledgement

This work was funded in part by VA merit review project, NHLBI at National Institutes of Health, R01-HL68094 and P01-HL013262-31 (BDS) as well as an American Heart Association post-doctoral fellowship grant 0525981T (YX).

References

- 1.Xu Y, Wang L, Buttice G, Sengupta PK, Smith BD. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:49134–49144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309003200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu Y, Wang L, Buttice G, Sengupta PK, Smith BD. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:41319–41332. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404174200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Myllyharju J, Kivirikko KI. Trends Genet. 2004;20:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hauser C, Schuettengruber B, Bartl S, Lagger G, Seiser C. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:7820–7830. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.22.7820-7830.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biade S, Stobbe CC, Boyd JT, Chapman JD. Int J Radiat Biol. 2001;77:1033–1042. doi: 10.1080/09553000110066068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mishra SK, Mandal M, Mazumdar A, Kumar R. FEBS Lett. 2001;507:88–94. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02951-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loury R, Sassone-Corsi P. Methods. 2003;31:40–48. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(03)00086-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tishchenko LI, Miul'berg AA, Ashmarin IP. Biokhimiia. 1971;36:595–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krieger DE, Levine R, Merrifield RB, Vidali G, Allfrey VG. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:332–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boffa LC, Vidali G, Mann RS, Allfrey VG. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:3364–3366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hendzel MJ, Davie JR. Biochem J. 1991;273(Pt 3):753–758. doi: 10.1042/bj2730753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jenuwein T, Allis CD. Science. 2001;293:1074–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1063127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boggs BA, Cheung P, Heard E, Spector DL, Chinault AC, Allis CD. Nat Genet. 2002;30:73–76. doi: 10.1038/ng787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fournier C, Goto Y, Ballestar E, Delaval K, Hever AM, Esteller M, Feil R. Embo J. 2002;21:6560–6570. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strahl BD, Allis CD. Nature. 2000;403:41–45. doi: 10.1038/47412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boffa LC, Walker J, Chen TA, Sterner R, Mariani MR, Allfrey VG. Eur J Biochem. 1990;194:811–823. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb19474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuo MH, Allis CD. Bioessays. 1998;20:615–626. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199808)20:8<615::AID-BIES4>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walia H, Chen HY, Sun JM, Holth LT, Davie JR. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:14516–14522. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.23.14516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alland L, Muhle R, Hou H, Jr., Potes J, Chin L, Schreiber-Agus N, DePinho RA. Nature. 1997;387:49–55. doi: 10.1038/387049a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laherty CD, Yang WM, Sun JM, Davie JR, Seto E, Eisenman RN. Cell. 1997;89:349–356. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80215-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao L, Cueto MA, Asselbergs F, Atadja P. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:25748–25755. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111871200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dangond F, Henriksson M, Zardo G, Caiafa P, Ekstrom TJ, Gray SG. Int J Oncol. 2001;19:773–777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kasten MM, Dorland S, Stillman DJ. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4852–4858. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buggy JJ, Sideris ML, Mak P, Lorimer DD, McIntosh B, Clark JM. Biochem J. 2000;350(Pt 1):199–205. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dangond F, Hafler DA, Tong JK, Randall J, Kojima R, Utku N, Gullans SR. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;242:648–652. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.8033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fischle W, Emiliani S, Hendzel MJ, Nagase T, Nomura N, Voelter W, Verdin E. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:11713–11720. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.11713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grozinger CM, Hassig CA, Schreiber SL. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:4868–4873. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.4868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fischer DD, Cai R, Bhatia U, Asselbergs FA, Song C, Terry R, Trogani N, Widmer R, Atadja P, Cohen D. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:6656–6666. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108055200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guardiola AR, Yao TP. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:3350–3356. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109861200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kao HY, Lee CH, Komarov A, Han CC, Evans RM. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:187–193. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108931200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kyrylenko S, Kyrylenko O, Suuronen T, Salminen A. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60:1990–1997. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3090-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thiagalingam S, Cheng KH, Lee HJ, Mineva N, Thiagalingam A, Ponte JF. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;983:84–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb05964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones PL, Veenstra GJ, Wade PA, Vermaak D, Kass SU, Landsberger N, Strouboulis J, Wolffe AP. Nat Genet. 1998;19:187–191. doi: 10.1038/561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Y, Ng HH, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Bird A, Reinberg D. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1924–1935. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.15.1924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hassig CA, Tong JK, Fleischer TC, Owa T, Grable PG, Ayer DE, Schreiber SL. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:3519–3524. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Y, Iratni R, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Reinberg D. Cell. 1997;89:357–364. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80216-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Y, Sun ZW, Iratni R, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Hampsey M, Reinberg D. Mol Cell. 1998;1:1021–1031. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sengupta P, Xu Y, Wang L, Widom R, Smith BD. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:21004–21014. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413191200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sengupta PK, Fargo J, Smith BD. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:24926–24937. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111712200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sengupta PK, Erhlich M, Smith BD. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:36649–36655. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schreiber E, Matthias P, Muller MM, S. W. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:6419. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.15.6419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goldberg H, Helaakoski T, Garrett LA, Karsenty G, Pellegrino A, Lozano G, Maity S, de Crombrugghe B. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:19622–19630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang X, Wharton W, Yuan Z, Tsai SC, Olashaw N, Seto E. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:5106–5118. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.12.5106-5118.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sengupta S, Smith EM, Kim K, Murnane MJ, Smith BD. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1789–1797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sengupta PK, Smith BD. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1443:75–89. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(98)00188-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chiba T, Yokosuka O, Fukai K, Hirasawa Y, Tada M, Mikata R, Imazeki F, Taniguchi H, Iwama A, Miyazaki M, Ochiai T, Saisho H. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:1185–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zika E, Greer SF, Zhu XS, Ting JP. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:3091–3102. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.9.3091-3102.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zika E, Ting JP. Curr Opin Immunol. 2005;17:58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mudhasani R, Fontes JD. Mol Immunol. 2005;42:673–682. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang AH, Gregoire S, Zika E, Xiao L, Li CS, Li H, Wright KL, Ting JP, Yang XJ. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:29117–29127. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500295200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Medugno L, Florio F, De Cegli R, Grosso M, Lupo A, Costanzo P, Izzo P. Gene. 2005;359:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Matsumura T, Suzuki T, Aizawa K, Munemasa Y, Muto S, Horikoshi M, Nagai R. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:12123–12129. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410578200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kang JE, Kim MH, Lee JA, Park H, Min-Nyung L, Auh CK, Hur MW. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2005;16:23–30. doi: 10.1159/000087728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhao S, Venkatasubbarao K, Li S, Freeman JW. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2624–2630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chiba T, Yokosuka O, Fukai K, Kojima H, Tada M, Arai M, Imazeki F, Saisho H. Oncology. 2004;66:481–491. doi: 10.1159/000079503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Niki T, Rombouts K, De Bleser P, De Smet K, Rogiers V, Schuppan D, Yoshida M, Gabbiani G, Geerts A. Hepatology. 1999;29:858–867. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rombouts K, Niki T, Wielant A, Hellemans K, Geerts A. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2001;64:239–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rombouts K, Niki T, Greenwel P, Vandermonde A, Wielant A, Hellemans K, De Bleser P, Yoshida M, Schuppan D, Rojkind M, Geerts A. Exp Cell Res. 2002;278:184–197. doi: 10.1006/excr.2002.5577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brunet A, Sweeney LB, Sturgill JF, Chua KF, Greer PL, Lin Y, Tran H, Ross SE, Mostoslavsky R, Cohen HY, Hu LS, Cheng HL, Jedrychowski MP, Gygi SP, Sinclair DA, Alt FW, Greenberg ME. Science. 2004;303:2011–2015. doi: 10.1126/science.1094637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van der Horst A, Tertoolen LG, de Vries-Smits LM, Frye RA, Medema RH, Burgering BM. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:28873–28879. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401138200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sakaguchi K, Herrera JE, Saito S, Miki T, Bustin M, Vassilev A, Anderson CW, Appella E. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2831–2841. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.18.2831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.You H, Mak TW. Cell Cycle. 2005;4 doi: 10.4161/cc.4.1.1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Furia B, Deng L, Wu K, Baylor S, Kehn K, Li H, Donnelly R, Coleman T, Kashanchi F. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:4973–4980. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107848200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Braun H, Koop R, Ertmer A, Nacht S, Suske G. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:4994–5000. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.24.4994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vervoorts J, Luscher-Firzlaff JM, Rottmann S, Lilischkis R, Walsemann G, Dohmann K, Austen M, Luscher B. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:484–490. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Boyes J, Byfield P, Nakatani Y, Ogryzko V. Nature. 1998;396:594–598. doi: 10.1038/25166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Simonsson M, Heldin CH, Ericsson J, Gronroos E. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:21797–21803. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503134200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Barlev NA, Liu L, Chehab NH, Mansfield K, Harris KG, Halazonetis TD, Berger SL. Mol Cell. 2001;8:1243–1254. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00414-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ito A, Lai CH, Zhao X, Saito S, Hamilton MH, Appella E, Yao TP. Embo J. 2001;20:1331–1340. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.6.1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Luo J, Li M, Tang Y, Laszkowska M, Roeder RG, Gu W. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:2259–2264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308762101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Accili D, Arden KC. Cell. 2004;117:421–426. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00452-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gajiwala KS, Burley SK. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2000;10:110–116. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(99)00057-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Blanchard F, Chipoy C. Drug Discov Today. 2005;10:197–204. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(04)03309-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Barnes PJ, Adcock IM, Ito K. Eur Respir J. 2005;25:552–563. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00117504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nebbioso A, Clarke N, Voltz E, Germain E, Ambrosino C, Bontempo P, Alvarez R, Schiavone EM, Ferrara F, Bresciani F, Weisz A, de Lera AR, Gronemeyer H, Altucci L. Nat Med. 2005;11:77–84. doi: 10.1038/nm1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ito K, Ito M, Elliott WM, Cosio B, Caramori G, Kon OM, Barczyk A, Hayashi S, Adcock IM, Hogg JC, Barnes PJ. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1967–1976. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhang Z, Yamashita H, Toyama T, Sugiura H, Ando Y, Mita K, Hamaguchi M, Hara Y, Kobayashi S, Iwase H. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005 doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-6001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hatamochi A, Paterson B, de Crombrugghe B. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:11310–11314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]