Abstract

Cross-talk between ethylene and jasmonate signaling pathways determines the activation of a set of defense responses against pathogens and herbivores. However, the molecular mechanisms that underlie this cross-talk are poorly understood. Here, we show that ethylene and jasmonate pathways converge in the transcriptional activation of ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR1 (ERF1), which encodes a transcription factor that regulates the expression of pathogen response genes that prevent disease progression. The expression of ERF1 can be activated rapidly by ethylene or jasmonate and can be activated synergistically by both hormones. In addition, both signaling pathways are required simultaneously to activate ERF1, because mutations that block any of them prevent ERF1 induction by any of these hormones either alone or in combination. Furthermore, 35S:ERF1 expression can rescue the defense response defects of coi1 (coronative insensitive1) and ein2 (ethylene insensitive2); therefore, it is a likely downstream component of both ethylene and jasmonate signaling pathways. Transcriptome analysis in Col;35S:ERF1 transgenic plants and ethylene/jasmonate-treated wild-type plants further supports the notion that ERF1 regulates in vivo the expression of a large number of genes responsive to both ethylene and jasmonate. These results suggest that ERF1 acts downstream of the intersection between ethylene and jasmonate pathways and suggest that this transcription factor is a key element in the integration of both signals for the regulation of defense response genes.

INTRODUCTION

Plants have developed both constitutive and inducible barriers for defense against pest and pathogen attack. Some of the inducible defenses have been shown to depend on the concerted action of two phytohormones, ethylene and jasmonate (Feys and Parker, 2000; McDowell and Dangl, 2000; Glazebrook, 2001; Thomma et al., 2001).

In response to different pathogens, jasmonate and ethylene cooperate to synergistically induce defense genes such as PR1b, PR5 (osmotin), and PDF1.2 (Xu et al., 1994; Penninckx et al., 1998). In the case of PDF1.2, compelling evidence has shown that the induction of this gene upon Alternaria brassicicola infection of Arabidopsis depends on the concomitant activation of both signaling pathways (Penninckx et al., 1996, 1998). In addition, genetic evidence on the implication of both hormonal pathways in the response to pathogens also has been provided. Mutations that impair jasmonate signaling (coi1 [coronative insensitive1] and jar1 [jasmonic acid resistant1]) or synthesis (fatty acid desaturase [fad]3-2, fad7-2, and fad8) resulted in an increased susceptibility of Arabidopsis plants to different fungal pathogens, such as Botrytis cinerea, A. brassicicola, Plectosphaerella cucumerina, Pythium spp (Staswick et al., 1998; Thomma et al., 1998, 2000; Vijayan et al., 1998), or insects, such as Bradysia impatiens (McConn et al., 1997). Similarly, ethylene insensitivity has been shown to enhance the susceptibility of different plant species to several fungi, including Septoria glycines, Rhizoctonia solani, Pythium spp, B. cinerea, and P. cucumerina (Knoester et al., 1998; Hoffman et al., 1999; Thomma et al., 1999), and to the soft-rot bacterium Erwinia carotovora (Norman-Setterblad et al., 2000). In addition, induced systemic resistance is blocked in jar1 and etr1 (ethylene resistant1) mutants impaired in their response to jasmonate and ethylene, respectively (Pieterse et al., 1996, 1998).

In addition, work with transgenic plants also supports the implication of these hormones in resistance against different pathogens. Constitutive expression of ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR1 (ERF1), a downstream component of the ethylene signaling pathway (Solano et al., 1998), increases Arabidopsis resistance to B. cinerea and P. cucumerina (Berrocal-Lobo et al., 2002). The application of exogenous methyl jasmonate to Arabidopsis plants reduces disease development from several fungi, such as A. brassicicola, B. cinerea, and P. cucumerina, in a dose-dependent manner (Thomma et al., 2000).

In addition to their role in the response to pathogen attack, ethylene and jasmonate regulate a wide variety of physiological processes in plants, including the activation of specific responses to different types of stress. How the plant selects the correct set of responses to a particular stress using the same two hormones (ethylene and jasmonate) remains poorly understood. The emerging picture is that the type of interaction that is established between these hormones after a given stress determines the type of responses that will be activated. Different types of interactions (both positive and negative) between ethylene and jasmonate have been described. For instance, ethylene is required for ozone-induced cell death in Arabidopsis, and this effect is antagonized by jasmonate (Rao and Davis, 1999; Overmyer et al., 2000; Rao et al., 2000). Another example of negative interaction is the participation of both hormones in the formation of the apical hook. Ethylene is required for hook development, and mutants that overproduce ethylene (eto) or that constitutively respond to the hormone (ctr1) develop an exaggerated apical hook (Wang et al., 2002). Jasmonate also antagonizes the effect of ethylene, in this case by preventing the formation of the apical hook even in ctr1 (Ellis and Turner, 2001).

The reciprocal type of negative interaction between these hormones (ethylene repressing jasmonate-dependent responses) also can be exemplified in the case of the wound response in Arabidopsis. In this plant, wounding promotes the synthesis of both jasmonate and ethylene. Jasmonate systemically induces the expression of several wound-responsive genes, whereas the ethylene synthesized locally represses the expression of these genes at the wound site. This negative interaction between the two hormones ensures the correct spatial pattern of expression of systemically induced genes (Rojo et al., 1999).

By contrast, a positive interaction between jasmonate and ethylene is responsible for the induction of proteinase inhibitors (PIN) genes after wounding in tomato. Although ethylene alone is not able to induce PIN expression, it cooperates with jasmonate to synergistically induce these genes (O'Donnell et al., 1996).

In summary, increasing evidence suggests that the set of defenses activated in plants in response to different types of stress (or developmental cues) finally depends on the type of interaction (positive or negative) between these hormonal signaling pathways rather than on the independent contribution of each hormone. However, in spite of the accumulating data, the molecular mechanisms that underlie these positive or negative interactions are largely unknown. Thus, a thorough knowledge at the molecular level of how cross-talk between ethylene and jasmonate pathways is regulated appears essential to understanding how plants activate the correct responses to a given stress, which is a necessary step to rationally improve these responses.

We have shown previously that ERF1 is a key element in the response to different necrotrophic pathogens. ERF1 is upregulated upon the infection of Arabidopsis by B. cinerea, and its constitutive expression in transgenic Arabidopsis plants is sufficient to confer resistance to several necrotrophic fungi, such as B. cinerea and P. cucumerina (Berrocal-Lobo et al., 2002). Here, we show the participation of ERF1 in jasmonate-mediated responses and investigate its role in the cross-talk between the ethylene and jasmonate pathways in plant defense. Our results indicate that ERF1 is a downstream component of both signaling pathways and suggest that it may play a key role in the integration of both signals to activate ethylene/jasmonate-dependent responses to pathogens.

RESULTS

ERF1 Is Upregulated by Jasmonate

Because the induction of the pathogenesis-related (PR) gene PDF1.2, a likely target of ERF1 (Solano et al., 1998), by A. brassicicola depends on the concerted action of the ethylene and jasmonate signaling pathways (Penninckx et al., 1998), we tested whether ERF1 would respond to jasmonate in addition to ethylene. Four-week-old soil-grown Arabidopsis plants were treated with jasmonate, and the accumulation of ERF1 transcripts was monitored at different times. As shown in Figure 1, jasmonate treatment of wild-type Arabidopsis plants resulted in a rapid and transient induction of ERF1 expression. ERF1 mRNA started to accumulate at 30 min after jasmonate treatment (Figure 1A) and returned to the basal level after 10 h (Figure 1B), suggesting that ERF1 is an early jasmonate-responsive gene. Similar results were obtained using liquid-cultured Arabidopsis plants (data not shown). In contrast to jasmonate, ethylene promoted a longer lasting induction of ERF1 expression (Figure 1B) (Solano et al., 1998). In addition, the treatment of wild-type plants with both ethylene and jasmonate had a synergistic effect on ERF1 expression (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

RNA Gel Blot Analysis of the Induction of ERF1 Expression by Jasmonate (A), and Synergistic Effect of Ethylene and Jasmonate on the Expression of ERF1, b-CHI, and PDF1.2 (B).

Four-week-old wild-type Arabidopsis plants were treated with 100 ppm of ethylene (E), 50 μM jasmonic acid (JA), both (EJA), or not treated (A [air]) for the indicated times. Twenty micrograms of total RNA was loaded per lane, and blots were hybridized with the indicated probes and rDNA as a loading control.

A similar effect of ethylene and jasmonate also was observed for b-CHI, a PR gene that is a likely target of ERF1 (Solano et al., 1998). The expression of this gene was upregulated by jasmonate and by ethylene, and the accumulation of transcripts was potentiated by the simultaneous application of both hormones (Figure 1B).

The expression of PDF1.2 was induced at 6 h after jasmonate treatment, but no induction by ethylene was observed during the first 10 h. A synergistic effect of ethylene and jasmonate on the induction of PDF1.2 was observed at later times (24 to 48 h after hormone application; data not shown) (Penninckx et al., 1998).

These results indicate that ERF1 is an early ethylene- and jasmonate-responsive gene and suggest that ERF1 may be a common component of both the ethylene and jasmonate signaling pathways.

ERF1 Induction by Ethylene or Jasmonate Requires Both Hormone-Signaling Pathways

Because treatment with one hormone can alter the endogenous levels of others, we analyzed the induction of ERF1 expression in mutant backgrounds that block either ethylene or jasmonate signaling pathways (ein2 and coi1, respectively). Four-week-old Arabidopsis wild-type plants, and ein2 and coi1 mutants, were treated with ethylene (100 ppm), jasmonate (50 μM), or both hormones simultaneously, and ERF1 mRNA levels were examined by RNA gel blot analysis in RNA samples prepared after 6 h of treatment. As shown in Figure 2, mutation in the EIN2 gene prevented the induction of ERF1 not only by ethylene but also by jasmonate and the combination of both hormones. Similarly, the coi1 mutation prevented the induction of ERF1 in response to the three treatments examined (jasmonate, ethylene, and both hormones simultaneously).

Figure 2.

RNA Gel Blot Analysis of ERF1 and b-CHI Induction by Jasmonate and Ethylene in Different Mutant Backgrounds.

Four-week-old wild-type (WT) plants and coi1 and ein2-5 mutants were treated with 100 ppm of ethylene (E), 50 μM jasmonic acid (JA), both (EJA), or not treated (A [air]) for 6 h. Twenty micrograms of total RNA was loaded per lane, and blots were hybridized with the indicated probes and rDNA as a loading control.

Similar results were obtained for the ERF1 target b-CHI (Figure 2). Mutations at EIN2 or COI1 prevented the upregulation of b-CHI by ethylene or jasmonate and their synergy. These results indicate that both signaling pathways are required simultaneously for the activation of ERF1 and ERF1 targets.

This apparent paradox (the simultaneous requirement of both pathways for ERF1 expression, when each hormone alone is sufficient to induce its expression independently) can be explained by invoking a basal level of activity in both pathways in the wild type that is not sufficient to activate ERF1 expression but that is required for responsiveness to either hormone. Such basal activities would be compromised in the respective insensitive mutants, preventing responses to either of the hormones.

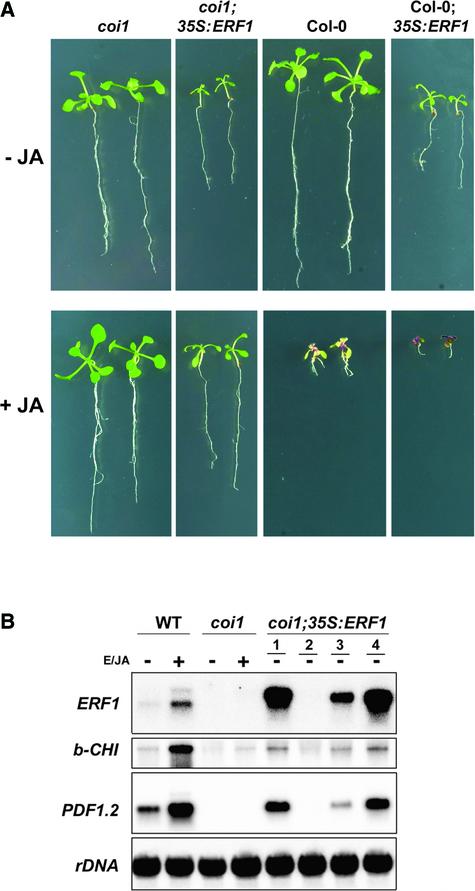

ERF1 Is Sufficient to Restore PR Gene Expression in coi1

These results suggested that ERF1 is a common downstream element of the ethylene and jasmonate pathways that may integrate both signals for the regulation of ethylene/jasmonate-responsive genes. To test this idea, we analyzed whether constitutive ERF1 expression in transgenic plants could bypass the need for COI1 in the expression of the ethylene/jasmonate-responsive genes b-CHI and PDF1.2, as demonstrated for EIN2 (Solano et al., 1998). To this end, we overexpressed ERF1 in a coi1 mutant background (coi1;35S:ERF1) and analyzed its phenotype and the expression of b-CHI and PDF1.2. As shown in Figure 3A, before jasmonate treatment, coi1;35S:ERF1 plants were similar to Col-0;35S:ERF1 plants. Both types of plants were smaller than their original parents (coi1 and Col-0, respectively), with a characteristic elongated shape of the leaves (Solano et al., 1998). The only apparent difference between the two types of transformants was that coi1;35S:ERF1, like coi1, was fully sterile (data not shown). In the presence of jasmonate, however, coi1;35S:ERF1 mutants were as insensitive to the hormone as coi1, at least with respect to root growth and anthocyanin accumulation.

Figure 3.

Phenotypic Analysis of coi1;35S:ERF1 Plants.

(A) Two-week-old wild-type Arabidopsis plants, coi1 mutants, and ERF1-expressing transgenic plants in wild-type or coi1 backgrounds were grown on agar plates containing (+JA) or not containing (−JA) 50 μM jasmonic acid.

(B) RNA gel blot analysis of the expression of ERF1, b-CHI, and PDF1.2 in coi1;35S:ERF1 plants. Four-week-old wild-type (WT) Arabidopsis plants, coi1 mutants, and four (lanes 1 to 4) independent transgenic lines expressing ERF1 in the coi1 background, grown in soil, were treated (+) or not treated (−) with 100 ppm of ethylene and 50 μM jasmonic acid (E/JA) for 24 h. Total RNA was extracted from these plants, and 20 μg was loaded per lane. The RNA gel blot was hybridized with the indicated probes and rDNA as a loading control. None of the transgenic coi1;35S:ERF1 lines was treated with ethylene and jasmonic acid.

In contrast to these apparently additive phenotypes of 35S:ERF1 and coi1, ERF1 expression bypassed the need for COI1 in the expression of PR genes. As shown in Figure 3B, expression of b-CHI, PDF1.2, and ERF1 was induced in wild-type plants after 24 h of treatment with ethylene and jasmonate, whereas mutations in COI1 fully prevented the induction of these three genes by these hormones. However, as in the case of ERF1 expression in wild-type plants, transgenic ERF1 expression in coi1 mutants resulted in the constitutive expression of both b-CHI and PDF1.2 in nontreated plants (Figure 3B, lines 1, 3, and 4). In transgenic line 2, which did not show detectable levels of ERF1, none of the targets was expressed either, further supporting the notion that the expression of b-CHI and PDF1.2 in the transgenic plants depends on ERF1.

These results demonstrate that 35S:ERF1 can rescue the defense response defects of coi1, as has been shown for ein2 (Solano et al., 1998); therefore, ERF1 is a likely downstream target of both the ethylene and jasmonate signaling pathways. Nevertheless, although ERF1 is sufficient to restore the expression of PR genes (b-CHI and PDF1.2) in ein2 and coi1, it does not suppress all ethylene- or jasmonate-related deficiencies in these mutants (e.g., development of exaggerated hook, male sterility, anthocyanin accumulation, etc.). This finding suggests that although ERF1 acts downstream of EIN2 and COI1, it regulates only a subset of the genes that are responsive to ethylene and jasmonate, most likely those involved in pathogen responses, such as b-CHI and PDF1.2, whose expression depends simultaneously on both hormones.

Transcriptome Analysis of Col-0;35S:ERF1 Plants

To investigate the involvement of ERF1 in the regulation of the expression of PR genes, and to further understand why 35S:ERF1 transgenic plants are highly resistant to pathogens (Berrocal-Lobo et al., 2002), a transcriptome analysis of Col-0;35S:ERF1 plants was performed using the Arabidopsis GeneChip from Affymetrix, which allows the simultaneous monitoring of 8000 genes. Because the expression of the known targets of ERF1 (b-CHI and PDF1.2) depends on both ethylene and jasmonate, expression profiling of 35S:ERF1 transgenic plants was compared with that of wild-type plants untreated or treated simultaneously with ethylene and jasmonate for 6 h. The diagrams in Figure 4 summarize the number of genes with altered expression patterns identified in two independent experiments. Group I represents genes exclusively induced (Figure 4A) or repressed (Figure 4B) by ethylene/jasmonate in wild-type plants, group II represents genes constitutively expressed or repressed in transgenic plants, and group III represents genes common to both (constitutively expressed/repressed in Col-0;35S:ERF1 and induced/repressed by ethylene/jasmonate in wild-type plants).

Figure 4.

Venn Diagrams of Results from the Transcriptome Analysis.

Numbers in overlapping or nonoverlapping areas of the diagrams represent the numbers of genes induced (A) or repressed (B) by treatment of 4-week-old wild-type plants with 100 ppm of ethylene and 50 μM jasmonic acid (E/JA) for 6 h or expressed differentially in Col-0;35S:ERF1 versus untreated wild-type plants. Numbers in parentheses represent the number of defense-related genes. Group I, genes induced/repressed exclusively in Col-0 plants by E/JA; group II, genes constitutively expressed/repressed in Col-0;35S:ERF1 transgenic plants and not induced/repressed by E/JA (6 h of treatment) in Col-0 plants; group III, overlapping genes (genes induced/repressed by E/JA in Col-0 and constitutively expressed/repressed in Col-0;35S:ERF1 transgenic plants).

As shown in Figure 4A, 164 genes were constitutively expressed in Col-0;35S:ERF1 plants (136 in group II plus 28 in group III), and 77 genes were upregulated after 6 h of treatment with ethylene and jasmonate in wild-type plants (49 in group I plus 28 in group III), both compared with nontreated wild-type plants. Twenty-eight genes (group III) were common to both groups; therefore, >36% of the genes induced by ethylene/jasmonate in wild-type plants were expressed constitutively in Col-0;35S:ERF1. Moreover, a high percentage of the genes in group III (71.4%; 20 genes) and in group II (39.7%; 54 genes) have been shown previously to be involved in plant defense (Table 1). Two major conclusions can be drawn from these results: (1) ERF1 plays a major role in the regulation of the expression of ethylene/jasmonate-responsive genes; and (2) a high number of the ERF1-regulated genes are related to defense.

Table 1.

Defense-Related Genes Upregulated in Col-0;35S:ERF1

| Fold Change

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accession No. | Gene Name | Product Description | Col E/JA | 35S:ERF1 | Ref. |

| CAA63009 | ASP | Cys-rich antifungal protein 1, anther specific | 15.7 | 149.6 | 1 |

| AF076277 | ERF1 | Ethylene response factor 1 | 15.5 | 128.9 | 2 |

| CAB45069 | –a | Putative storage protein/wound–inducible endochitin | – | 93.8 | 3 |

| AAB64047 | CHI | Putative endochitinase | – | 47 | 4 |

| CAB42592 | – | Berberine bridge–forming enzyme | – | 27.8 | 5 |

| CAB39936 | OSL3 | Osmotin precursor | 4.8 | 24.9 | 6 |

| CAA57943 | SRG2At | β-Glucosidase | – | 20.8 | 7 |

| AAA32769 | – | Basic chitinase | 4.3 | 17.9 | 8 |

| BAA82810 | ChiB | Basic endochitinase | 4.8 | 17 | 8 |

| AAB40594 | AtSS-2 | Strictosidine synthase | – | 16.6 | 9 |

| CAB10405 | – | β-1,3-glucanase class I precursor | 11.6 | 13.7 | 10 |

| AAC28502 | – | β-glucosidase | – | 12.4 | 7 |

| AAA32863 | – | PR1-like | – | 11.9 | 11 |

| AAB63634 | JIP | Jasmonate-inducible protein isolog | – | 10.4 | 12 |

| AAC69380 | – | Xyloglucan endotransglycosylase | – | 10.2 | 13 |

| CAA48026 | Eli3-2 | Plant defense gene | – | 7.7 | 14 |

| CAA20585 | PR1 | Pathogenesis-related protein 1 precursor | – | 7.3 | 11 |

| AY059757 | – | Linalool synthase-like | – | 7 | 15 |

| AAD00509 | GLP9 | Germin-like protein | – | 7 | 16 |

| CAA19698 | – | Putative chitinase | – | 6.4 | 8 |

| CAA23047 | – | WRKY53 | – | 5.8 | 9 |

| AAB82640 | PME | Pectin methylesterase | – | 5.6 | 9 |

| CAA65419 | PR1 | Pathogenesis-related protein 1 | – | 5.2 | 16 |

| AAD34694 | – | Similar to latex-abundant protein | – | 5.2 | 16 |

| AAD03416 | CYP79B2 | Cytochrome P450 | – | 5 | 17 |

| AAA32827 | LOX1 | Lipoxygenase 1 | 2.7 | 4.9 | 16 |

| AAC16094 | – | β-Glucosidase | – | 4.7 | 7 |

| AAB60774 | – | WRKY6 | – | 4.5 | 18 |

| AAA62426 | CCoAMT | S-Adenosyl-l-Meth:trans–caffeoyl–coenzyme A 3-O-methyltransferase | – | 4.3 | 19 |

| AAC00608 | MLP | Similar to major latex protein | – | 4.2 | 16 |

| CAB42588 | – | Berberine bridge–forming enzyme | – | 4.2 | 9 |

| CAA20584 | PR1 | Pathogenesis-related protein 1 precursor | – | 4.1 | 11 |

| AAD21459 | HIN1 | Similar to harpin-inducible protein | – | 3.8 | 20 |

| AAB63631 | JIP | Jasmonate-inducible protein isolog | – | 3.5 | 12 |

| CAA17549 | CAD | Cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase–like protein | – | 3.4 | 9 |

| AAA20642 | HEL | Pre-hevein-like | – | 3 | 12 |

| CAB42594 | – | Berberine bridge–forming enzyme | – | 3 | 5 |

| AAA32865 | – | Thaumatin-like | – | 2.9 | 11 |

| AAD25759 | BBE | Berberine bridge enzyme | – | 2.8 | 9 |

| CAB45070 | – | Putative storage protein/wound–inducible endochitin | 4.3 | 2.8 | 3 |

| CAB45071 | – | Putative storage protein/wound–inducible endochitin | – | 2.7 | 3 |

| CAB45881 | BBE | Berberine bridge enzyme | – | 2.6 | 9 |

| CAB16771 | CYP81E1 | Cytochrome P450-like | 2.1 | 2.5 | 21 |

| AAC49117 | TSA1 | Trp synthase α chain | 3.8 | 2.4 | 17 |

| AAA32738 | ASA1 | Anthranilate synthase α subunit | 3 | 2.4 | 17 |

| AAD14487 | – | Aldo-keto reductase | – | 2.4 | 22 |

| AAA60380 | InGPS | Indole-3-glycerol phosphate synthase | 3.4 | 2.2 | 17 |

| AAC39479 | RbohD | Respiratory burst oxidase protein D | 1.8 | 2.2 | 9 |

| AAD24653 | GRP | Gly-rich protein | – | 2 | 9 |

| AAC64880 | – | Similar to 5-epi-aristolochene synthase/delta cadinene synthase | – | 73 | 15 |

| AAC95191 | GST | Putative glutathione S-transferase | – | 22.6 | 9 |

| P42043 | HMZ1 | Ferrochelatase I | – | 10.5 | 23 |

| CAA07352 | p9a | Peroxidase | – | 7.8 | 24 |

| CAA55654 | SRG1 | – | – | 6.1 | 25 |

| AAA19628 | NIT4 | Nitrilase | 3.9 | 4.9 | 26 |

| CAA77089 | –a | Blue copper binding–like protein | 2.6 | 4.8 | 16 |

| AAC95192 | GST | Putative glutathione S-transferase | 5.2 | 4 | 9 |

| CAA16797 | RLK | Receptor Ser/Thr kinase-like protein | – | 3.7 | 9 |

| AAD03365 | – | Putative disease resistance protein | – | 3.2 | – |

| CAA50677 | prxCb | Peroxidase | – | 3.1 | 27 |

| AAC31840 | EREBP | Ethylene response element binding protein | – | 3.1 | 9 |

| AF081067 | JR3 | IAA-Ala hydrolase | 2 | 3.1 | 12 |

| AAC20719 | – | Dioxygenase | – | 3.1 | 28 |

| AAD28243 | TPx2 | Peroxiredoxin | – | 2.5 | 29 |

| AAB47973 | – | Blue copper binding protein II | – | 2.5 | 16 |

| CAA52619 | – | β-Fructosidase | – | 2.5 | 30 |

| U75198 | GLP5 | Germin-like protein 5 | – | 2.4 | 31 |

| CAA74639 | GST11 | Glutathione S-transferase 11 | 3 | 2.2 | 9 |

| AAC95354 | RKC1 | Receptor-like protein kinase | – | 2.1 | 32 |

| AAC32912 | GST | Glutathione S-transferase | 2.8 | 2 | 9 |

| AAC02748 | CYP71A13 | Cytochrome P450 | – | 14.3 | 9 |

| AAC06158 | CYP76C2 | Cytochrome P450 | – | 8.3 | 9 |

| AAB64022 | – | Putative glucosyltransferase | – | 5.1 | 9 |

| AAB63623 | – | Cellulose synthase isolog | 2.8 | 3.1 | 9 |

Defense-related genes constitutively expressed in Col-0;35S:ERF1 transgenic plants (groups II and III in Figure 4A) compared with wild-type plants. The subset of these genes that also are induced by 6 h of ethylene/jasmonate treatment in wild-type plants are indicated in the Col E/JA column. Genes from this table used in the experiment of Figure 5 are highlighted in boldface letters. Included in this table are genes with a direct role in defense and oxidative stress or that are involved indirectly in defense responses (pathogen-induced genes, genes similar to defense genes in other plants, etc.), as described in the references as numbered in the table and listed below: 1, Terras et al., 1993; 2, Berrocal-Lobo et al., 2002; 3, Coleman and Chen, 1993; 4, Rasmussen et al., 1992; 5, Dittrich and Kutchan, 1991; 6, Capelli et al., 1997; 7, Sue et al., 2000; 8, Samac and Shah, 1994; 9, Cheong et al., 2002; 10, Chye and Cheung, 1995; 11, Uknes et al., 1992; 12, Reymond et al., 2000; 13, van Kan et al., 1992; 14, Kiedrowski et al., 1992; 15, Bohlmann et al., 1997; 16, Schenk et al., 2000; 17, Brader et al., 2001; 18, Chen et al., 2002; 19, Busam et al., 1997; 20, Lee et al., 2001; 21, Akashi et al., 1998; 22, Welle et al., 1991; 23, Roper and Smith, 1997; 24, Justesen et al., 1998; 25, Truesdell and Dickman, 1997; 26, Bartel and Fink, 1994; 27, Intapruk et al., 1994; 28, Ponce de Leon et al., 2002; 29, Baier and Dietz, 1996; 30, Sturm and Chrispeels, 1990; 31, Carter et al., 1998; 32, Ohtake et al., 2000.

–, not applicable.

The overlap between ERF1- and ethylene/jasmonate-regulated genes does not apply only to upregulated genes but to downregulated genes as well. As shown in Figure 4B, 35 genes were constitutively repressed in Col-0;35S:ERF1 plants (28 in group II plus 7 in group III) (Table 2), whereas 70 genes were repressed by ethylene/jasmonate treatment in wild-type Col-0 plants (63 in group I plus 7 in group III). Thus, 20% of the genes repressed in Col-0;35S:ERF1 plants also were repressed by ethylene and jasmonate (6 h of treatment) in wild-type plants.

Table 2.

Genes Downregulated in Col-0;35S:ERF1 Transgenic Plants

| Fold Change

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accession No. | Gene Name | Product Description | Col E/JA | 35S:ERF1 |

| AAD20908 | –a | Putative cell wall protein precursor | – | −51.8 |

| AAC41678 | Thi2.1 | Thionin | – | −18 |

| AAA97403 | AGL8 | Agamous-like 8 | – | −16.1 |

| CAB36809 | – | Subtilisin proteinase-like | – | −7.6 |

| AAC50042 | ATA20 | – | – | −5.1 |

| AAD20695 | ARF | Auxin response factor-like | −2.4 | −4.8 |

| AAC49698 | ICK1 | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor | −2.8 | −4.2 |

| CAB36525 | APG | Putative anther-specific proline-rich protein | −3 | −3.5 |

| CAA18852 | RBFA | Putative ribosome-binding factor | – | −3.4 |

| CAB09231 | AtMYB76 | R2R3-MYB transcription factor | −3.5 | −3.2 |

| AAD32811 | RR | Putative two-component response regulator | – | −3.2 |

| CAA19701 | – | Lectin-like protein | – | −3.1 |

| AAC69133 | – | Putative squamosa-promoter binding protein | – | −3.1 |

| BAA22095 | VSP | Vegetative storage protein | – | −3 |

| CAA06772 | Sqp1;1 | Squalene epoxidase | −10.4 | −2.8 |

| CAB56585 | SPL3 | Squamosa-promoter binding protein-like 3 | – | −2.5 |

| CAA38894 | cor6.6 | Cold-regulated 6.6 | – | −2.5 |

| AAD17422 | – | Putative esterase | – | −2.5 |

| AAC79099 | – | Putative oxidoreductase | −3.4 | −2.5 |

| AAC06175 | AGL20 | Agamous-like MADS box protein | – | −2.4 |

| AAD53103 | MYB28 | R2R3-MYB transcription factor | −2.5 | −2.3 |

| AAD20164 | ARF1 | Putative ARF1 auxin responsive transcription factor | – | −2.3 |

| CAB10528 | – | Thioesterase-like protein | – | −2.2 |

| CAB56589 | SPL10 | Squamosa-promoter binding protein–like 10 | – | −2.1 |

| AAG51381 | HBL2 | Class 2 nonsymbiotic hemoglobin | – | −2.1 |

| CAB10464 | RPP5 | Disease resistance RPP5–like protein | – | −2.1 |

| AAC00607 | – | Similar to ripening-induced protein | – | −2 |

| BAA23547 | COR47 | Cold-regulated 47 | – | −2 |

| AAD23043 | MYB | Putative MYB transcription factor | – | −2 |

Genes constitutively repressed in Col-0;35S:ERF1 transgenic plants (groups II and III in Figure 4B) compared with wild type plants. The subset of these genes that also are repressed by 6 h of ethylene/jasmonate treatment in wild type plants are indicated in the Col E/JA column.

–, not applicable.

The high number of defense-related genes whose expression was upregulated by ERF1 is fully consistent with our previous results demonstrating that ERF1-overexpressing plants are resistant to several pathogens (Berrocal-Lobo et al., 2002). Moreover, these results also confirm the major role that ERF1 plays in the regulation of ethylene/jasmonate-dependent defense gene expression and may help to identify new defense-related genes among those of unknown function (15 in group II and 9 in group I [Figure 4A]; see also supplemental data online).

The reliability of the microarray data was confirmed further by analysis of the expression of genes from different groups in response to ethylene, jasmonate, or both in wild-type, coi1, and ein2 plants. In all cases in which the intensity of the chip signal was high (see supplemental data online), a very good correlation between chip and RNA gel blot data was observed. However, when the intensity of the hybridization in the chip was low (see genes 20420at and 19121at in the supplemental data online), hybridization could not be detected by RNA gel blot techniques.

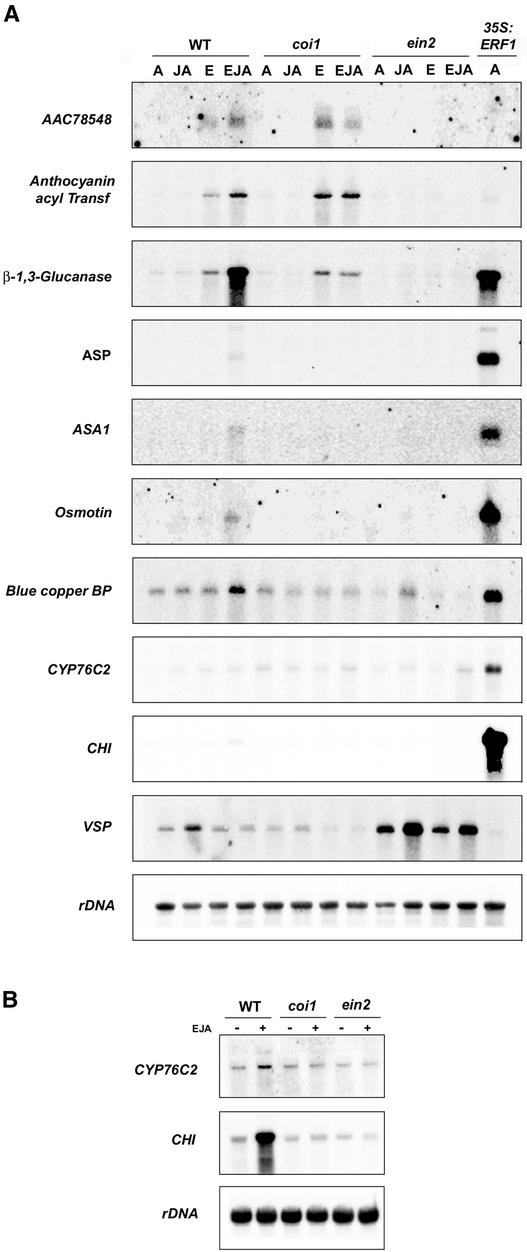

Genes AAC78548 and AAB95283 (Anthocyanin Acyl Transferase) represent examples of genes not regulated by ERF1 (not expressed in 35S:ERF1 plants but induced by ethylene/jasmonate treatment in wild-type plants; group I). As shown in Figure 5, these two genes were shown to be induced by ethylene in wild-type plants and coi1 mutants, but not in ein2, and were not expressed in Col-0;35S:ERF1 plants. These genes were not upregulated by jasmonate, which suggests, together with the results presented previously, that genes constitutively expressed in 35S:ERF1 plants may be only those induced simultaneously by ethylene and jasmonate but not regulated differentially by these hormones. This hypothesis was further supported by the expression of genes in group III and VSP. All genes from group III tested (β-1,3-Glucanase, ASP, Anthranilate Synthase, Osmotin, and Blue Copper Binding Protein) were shown to be induced synergistically by ethylene/jasmonate and expressed constitutively in Col-0;35S:ERF1 plants. In the case of VSP, its expression was regulated differentially by jasmonate and ethylene. Jasmonate upregulated VSP expression in wild-type plants, whereas ethylene had the opposite effect, because it prevented induction by jasmonate in wild-type plants, and ein2 mutants showed a constitutively high level of expression that could be increased further by jasmonate treatment (Figure 5) (Rojo et al., 1999). This gene was not expressed in Col-0;35S:ERF1 plants, again suggesting that ERF1 only regulates genes induced simultaneously by ethylene and jasmonate but not genes regulated differentially by these hormones.

Figure 5.

RNA Gel Blot Analysis of the Expression of Ethylene/Jasmonate- and/or ERF1-Regulated Genes Identified by Transcriptome Profiling.

Four-week-old wild-type (WT) plants and 35S:ERF1, coi1, and ein2-5 mutants were treated with either 100 ppm of ethylene (E), 50 μM jasmonic acid (JA), both (EJA), or not treated (A [air]) for 6 h (A) or 24 h (B). Ten micrograms of total RNA was loaded per lane, and blots were hybridized with the indicated probes and rDNA as a loading control.

The cytochrome P450 CYP76C2 and CHI are examples of genes specifically upregulated by ERF1 but not induced in ethylene/jasmonate-treated wild-type plants. Although genes in this group were not upregulated by ethylene/jasmonate after 6 h of treatment, the possibility cannot be excluded that, as with PDF1.2 (Figure 3B) (Solano et al., 1998), these genes may be upregulated by both hormones at later times. To address this possibility, we analyzed the expression of both genes (CYP76C2 and CHI) at 24 h after treatment with ethylene and jasmonate. As shown in Figure 5B, both genes were upregulated by the ethylene/jasmonate treatment in wild-type plants but not in the coi1 or ein2 mutants, demonstrating that these also are ethylene/jasmonate-responsive genes. These results suggest that genes in group II may represent genes also upregulated by both hormones at times later than the 6-h time point used for the microarray analysis.

In summary, the transcriptional profiling analysis indicates that ERF1 plays a key role in the regulation in vivo of the expression of genes that are induced simultaneously by ethylene and jasmonate but not of genes regulated differentially by these hormones, which mainly represent defense-related genes.

DISCUSSION

Ethylene and jasmonate are involved in the activation of defense responses to different plant pathogens. Here, we demonstrate that (1) transcription factor ERF1 is a downstream component of both ethylene and jasmonate pathways; (2) ERF1 expression requires both signaling pathways simultaneously; and (3) ERF1 is responsible for the transcriptional activation of ethylene/jasmonate-dependent defense-related genes. Together, these results suggest that ERF1 is a key integrator of ethylene and jasmonate signals in the regulation of ethylene/jasmonate-dependent defenses.

ERF1 Is a Common Component of the Ethylene and Jasmonate Pathways

As described in the Introduction, ethylene and jasmonate signaling pathways may interact, both positively and negatively, to co-regulate the expression of stress-responsive genes. This positive or negative cross-talk is supposed to define the response of plants to a given stress and has been documented in several instances: ozone-induced cell death (Rao and Davis, 1999; Overmyer et al., 2000; Rao et al., 2000), development of the apical hook (Ellis and Turner, 2001), wounding (O'Donnell et al., 1996; Rojo et al., 1999), and defense against pathogens (reviewed by Turner et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2002). The fact that the final outcome of the interaction between ethylene and jasmonate differs in the different responses suggests that alternative combinations of preexisting signals may fine-tune the responses of plants to their environment.

In spite of the accumulating data regarding cross-talk between ethylene and jasmonate pathways, no molecular mechanism has been proposed to explain these interactions; in fact, very limited data are available about molecular mechanisms of any type of cross-talk in plant signaling (for an example, see Blazquez and Weigel, 2000). Here, we show that ERF1 may explain at the molecular level the positive interaction between ethylene and jasmonate in the plant's response to pathogens (such as B. cinerea and P. cucumerina [Berrocal-Lobo et al., 2002]) by being an inducible factor that reacts rapidly and synergistically to both signals (ethylene and jasmonate) and that requires both signaling pathways simultaneously to be activated. ERF1 was identified previously as a downstream component of the ethylene signaling pathway, whose expression is regulated in vivo by EIN3, which binds to the ERF1 promoter (Solano et al., 1998). Here, ERF1 also was shown to be an early jasmonate-responsive gene. Because jasmonate does not induce ethylene synthesis in Arabidopsis (Rojo et al., 1999), the accumulation of the ERF1 mRNA soon after jasmonate treatment indicates that ERF1 responds directly to jasmonate. In agreement with this idea, ORCA3 has been described as a key component of the jasmonate response pathway in Catharanthus roseus (van der Fits and Memelink, 2000, 2001). In this plant species, ORCA3 regulates jasmonate-dependent responses through a jasmonate and elicitors response element (JERE). ORCA3 is very similar to ERF1, and its DNA binding site (JERE) is very similar to the ERF1 DNA target (GCC box), suggesting that in Arabidopsis, ERF1, or a highly related member of the ERF family, also may regulate the expression of genes in response to jasmonate and elicitors through a JERE-like element. In fact, the STRICTOSIDINE SYNTHASE gene, which is a target of ORCA3 in Catharanthus, also is upregulated by ERF1 in Arabidopsis (16.6-fold change; Table 1). This finding also suggests that ORCA3, like ERF1, may be an ethylene response factor.

The fact that ERF1 induction by jasmonate is dependent on EIN2 and that ERF1 induction by ethylene is dependent on COI1 demonstrates that both signaling pathways are required simultaneously for ERF1 activation and suggests that ERF1 is a downstream target of both the ethylene and jasmonate pathways, which act in parallel in the activation of this transcription factor to trigger defense responses. This idea is further supported by the synergistic induction of ERF1 by both hormones and is confirmed by the bypass, through ERF1 overexpression, of the requirement of COI1 and EIN2 for PDF1.2 and b-CHI expression (Solano et al., 1998). As mentioned above, it has been demonstrated previously that functional ethylene and jasmonate pathways are absolutely required for the expression of PDF1.2 (Penninckx et al., 1996, 1998), and our work extends this concept for b-CHI and ERF1. Mutations that impair responses to ethylene (such as ein2) or jasmonate (such as coi1) prevent the activation of these genes by either of the two hormones. We demonstrate that ERF1 is sufficient to activate PDF1.2 and b-CHI gene expression in these mutant backgrounds (coi1 and ein2; this work and Solano et al., 1998, respectively), suggesting that the expression of ERF1 is the only requirement for PDF1.2 and b-CHI expression and further confirming that ERF1 acts downstream of both signaling pathways.

We demonstrated previously that necrotrophic pathogens, such as B. cinerea, induce the expression of ERF1 and that ERF1 is sufficient to confer resistance to these fungi (Berrocal-Lobo et al., 2002). The requirement of both ethylene and jasmonate signaling pathways for the activation of ERF1 expression parallels the requirement of both signaling pathways for plant resistance to different necrotrophic pathogens (for review, see Thomma et al., 2001), further suggesting that ERF1 is a key component in the activation of plant defenses against necrotrophs.

ERF1-Regulated Genes Are Related Mainly to Defense

Transcriptome analysis is a powerful means by which to compare gene expression profiles and gather data to help reveal gene function (for an example, see Petersen et al., 2000). In our case, the objective of the transcriptome analysis was not to obtain a catalog of genes regulated early by ethylene and jasmonate, or expressed constitutively in ERF1-overexpressing plants, but to get a “genome-wide” glance at the type of genes that may be regulated by ERF1 and of the overlap between ERF1- and ethylene/jasmonate-regulated genes that would further extend our understanding of the role of ERF1 in the regulation of plant stress responses.

More than one-third of the genes induced after 6 h of treatment with ethylene and jasmonate were expressed constitutively in ERF1-overexpressing plants, and more than two-thirds of these genes have been reported to be involved in defense responses (Table 1). In fact, this is an underestimation, because many of the genes analyzed do not have a known function. By contrast, only a low percentage (12.5%) of the genes induced by ethylene and jasmonate (after 6 h), but not by ERF1 overexpression (genes in group I), are defense-related genes. These data highlight the instrumental role of ERF1 in the regulation of ethylene/jasmonate-dependent pathogen response genes. In fact, considering the total number of defense-related genes induced by ethylene and jasmonate (after 6 h) in wild-type plants, only 20% are independent of ERF1, whereas 80% also are expressed constitutively in untreated Col;35S:ERF1 transgenic plants. Among the total number of defense-related genes expressed constitutively in Col;35S:ERF1 plants (74 genes), 54 belong to group II (not induced in Col-0 plants after 6 h of ethylene and jasmonate treatment). These genes might represent late defense response genes, which could be induced by ethylene and jasmonate at later times. This possibility is exemplified clearly here by CYP76C2, CHI, and PDF1.2.

These results reflect the surprisingly high percentage of ethylene/jasmonate-dependent responses, especially those related to defense, that may be explained by the mere expression of ERF1 and suggest a pivotal role of ERF1 in the regulation of ethylene/jasmonate-dependent defense responses. In agreement with these results, several different groups recently demonstrated that ERF1 is induced after the infection of Arabidopsis plants with different pathogens (Berrocal-Lobo et al., 2002; Chen et al., 2002; Onate-Sanchez and Singh, 2002) and that constitutive expression of ERF1 enhances the resistance of Arabidopsis plants to several fungi (Berrocal-Lobo et al., 2002).

It is important to consider here that the ERF family is composed of a high number of genes in Arabidopsis; therefore, other members of this family, in addition to ERF1, could participate in vivo in the regulation of these defense-related genes. In fact, as with ERF1 (15.5-fold change), another member of the ERF family, AtERF2, was induced rapidly after ethylene and jasmonate treatment (3.5-fold change; see supplemental data online). This gene also was identified recently as a pathogen response gene, as was another member of the ERF family, AtERF1 (Chen et al., 2002). Therefore, it is possible that these three genes have redundant functions that make functional analysis in single mutants difficult. Double or triple mutants will likely be necessary to analyze the requirement of each gene in the activation of plant defense responses.

The participation of ERF1 in defense responses may not be restricted to fungal pathogens. In fact, among the genes upregulated by ERF1 are four enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of indole glucosinolates (ASA, InGPS, TSA, and CYP79B2), which have been implicated in defense against pathogens and herbivores, and the myrosinase binding protein, which is involved in the breakdown (and thus toxicity) of the glucosinolates (Halkier, 1999; Rask et al., 2000).

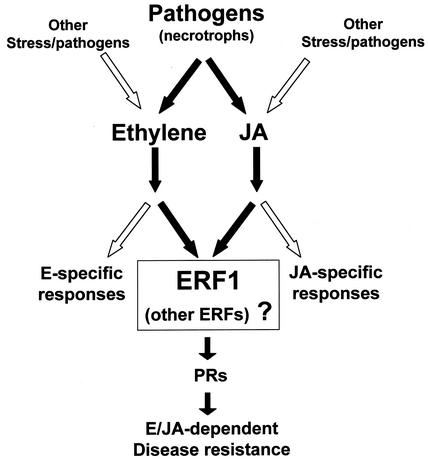

A simplified picture of our current view of the ethylene/jasmonate-dependent defense responses is shown in Figure 6. Challenge of Arabidopsis plants by some types of pathogens, such as the necrotrophic fungi described in the Introduction, or by some types of herbivores, starts a cascade of signaling events (black arrows) that involve the synthesis and subsequent activation of both the ethylene and jasmonate pathways simultaneously (Penninckx et al., 1998). This activation drives the expression of ERF1 (and possibly other members of the ERF family), which may be responsible for the integration of the signals from both pathways to activate the expression of pathogen response genes encoding defense-related proteins that prevent disease progression (Berrocal-Lobo et al., 2002; this work). In contrast to these ethylene/jasmonate-dependent defense responses, other types of pathogens or stresses induce the synthesis and activation of only one of these signaling pathways (white arrows), and this activation triggers the induction of ethylene- or jasmonate-specific responses. Thus, in summary, depending on the type of pathogen or stress, different types of defense responses can be induced in the plant through the correct activation of ethylene, jasmonate, or both signaling pathways.

Figure 6.

Scheme of the Ethylene/Jasmonate-Dependent Pathway of the Arabidopsis Response to Pathogens.

Infection by some types of pathogens induces the synthesis and subsequent activation of the ethylene and jasmonate pathways simultaneously (black arrows). As a consequence, ERF1 is activated transcriptionally; in turn, it activates the expression of defense-related genes that prevent disease progression. Other types of stress or pathogens (white arrows) induce the activation of only one of these signaling pathways and, therefore, ethylene- or jasmonate-specific responses.

METHODS

Biological Materials and Growth Conditions

The Columbia (Col-0) ecotype is the genetic background of all of the Arabidopsis thaliana plants used in this work (wild-type, coi1, ein2-5, and transgenic ERF1-expressing plants). The coi1;35S:ERF1 plants were obtained by transformation of coi1 heterozygous mutants with the 35S:ERF1-expressing construct (described previously by Solano et al., 1998) and subsequent selection of the F2 siblings on plates containing 50 μM jasmonate and 50 μM kanamycin. Before plating, seeds were surface-sterilized in 75% bleach and 0.5% Tween 20 and washed three times in sterile water. For RNA gel blot experiments, seedlings were selected on plates containing 50 μM kanamycin (transgenic plants), 50 μM jasmonate (coi1), or 10 μM 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ein2), transferred to soil, and grown in a phytochamber with a 16-h-light/8-h-dark photoperiod at 60% RH and 21°C. ABRC stock numbers for the transgenic lines used in this work are CS6142 and CS6143 (Col-0;35S:ERF1) and CS6144 and CS6145 (coi1;35S:ERF1).

RNA Gel Blot Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from frozen tissues harvested at different times after treatment using RNAwiz as described by the manufacturer (Ambion, Austin, TX). Extracted RNAs were subjected to electrophoresis on 1.5% formaldehyde/agarose gels and blotted to Hybond N+ membranes (Amersham). ERF1 probes were labeled with 100 μCi of α-32P-dCTP. All other probes were labeled with 50 μCi of α-32P-dCTP. Blots were exposed for 24 h on a PhosphorImager screen (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA).

Chip Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from frozen plant tissue treated (or not) with ethylene (100 ppm) and jasmonate (50 μM) using RNAwiz (Ambion). Poly(A)+ RNA was prepared using the Oligotex mRNA Midi Kit from Qiagen (Valencia, CA). Two micrograms of poly(A)+ was converted to double-stranded cDNA using the SuperScript Choice System (Gibco BRL) with a T7-(dT)24 primer incorporating a T7 RNA polymerase promoter (Genset, La Jolla, CA). Biotin-labeled cRNA was synthesized from 1 μg of double-stranded cDNA using the BioArray High Yield RNA Transcript Labeling Kit (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). Fifteen micrograms of biotin-labeled copy RNA was purified and fragmented by heating at 94°C for 35 min in a buffer containing 40 mM Tris-acetate, pH 8.1, 100 mM KOAc, and 30 mM MgOAc. Fragmented copy RNAs were hybridized with an Arabidopsis genome array (Affymetrix) for 16 h at 45°C in a buffer containing 100 mM Mes, 1 M Na+, 20 mM EDTA, 0.01% Tween 20, 0.1 mg/mL herring sperm DNA (Promega), and 0.5 mg/mL acetylated BSA (Gibco BRL). After removal of the hybridization mixture, the arrays were washed and then stained with streptavidin-phycoerythrin (Molecular Probes) and biotinylated goat anti-streptavidin antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) in the Affymetrix fluidics stations using standard procedures supplied by the manufacturer. Arrays were scanned using an Agilent GeneArray Scanner (Affymetrix).

Two replicate experiments were performed, and the results from both replicates were combined and classified using the comparison analysis algorithms provided with the Affymetrix software (MicroArray Suite MAS 4.0; http://www.affymetrix.com/products/software/specific/mas.affx) in the following manner. After global scaling of the arrays to an average intensity of 180 to 200 (to make all experiments comparable), genes were considered “induced” when they were determined to be “increased” in one replicate and “increased” or “marginal increased” in the other. “Repressed” genes were those determined to be “decreased” in one replicate and “decreased” or “marginal decreased” in the other. In addition, genes were considered “reliable induced genes” only if they were called “present” by the analysis software in the Experimental Channel in both replicates. Similarly, “reliable repressed genes” were those called “present” in the Baseline Channel in both replicates. Finally, only those genes whose expression difference increased or decreased twofold or greater in both replicates were included in the list of genes presented in Tables 1 and 2 and in the supplemental data online. To ensure the reliability of the data, mixtures of biological material were used in each replicate of the experiment.

Upon request, all novel materials described in this article will be made available in a timely manner for noncommercial research purposes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Paz-Ares, C. Castresana, J.M. Martínez-Zapater, J.M. Alonso, and M. Pernas for critical reading of the manuscript and stimulating discussions. We also thank K.D. Harshman (genomics facility at the Centro Nacional de Biotecnología) and J.C. Oliveros (ALMA Bioinformatics SL, Tres Cantos, Madrid, Spain) for their advice and help in the transcriptome analysis, and P. Paredes for excellent technical assistance. Seeds from coi1 were kindly provided by J.G. Turner. This work was financed by Grants 07G/0048/2000 and BIO2001-0567 to R.S. from the Comunidad de Madrid and the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología, respectively.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1105/tpc.007468.

Footnotes

Online version contains Web-only data.

References

- Akashi, T., Aoki, T., and Ayabe, S. (1998). CYP81E1, a cytochrome P450 cDNA of licorice (Glycyrrhiza echinata L.), encodes isoflavone 2′-hydroxylase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 251, 67–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baier, M., and Dietz, K.J. (1996). Primary structure and expression of plant homologues of animal and fungal thioredoxin-dependent peroxide reductases and bacterial alkyl hydroperoxide reductases. Plant Mol. Biol. 31, 553–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel, B., and Fink, G.R. (1994). Differential regulation of an auxin-producing nitrilase gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 6649–6653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrocal-Lobo, M., Molina, A., and Solano, R. (2002). Constitutive expression of ETHYLENE-RESPONSE-FACTOR1 in Arabidopsis confers resistance to several necrotrophic fungi. Plant J. 29, 23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazquez, M.A., and Weigel, D. (2000). Integration of floral inductive signals in Arabidopsis. Nature 404, 889–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohlmann, J., Steele, C.L., and Croteau, R. (1997). Monoterpene synthases from grand fir (Abies grandis): cDNA isolation, characterization, and functional expression of myrcene synthase, (−)-(4S)-limonene synthase, and (−)-(1S,5S)-pinene synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 21784–21792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brader, G., Tas, E., and Palva, E.T. (2001). Jasmonate-dependent induction of indole glucosinolates in Arabidopsis by culture filtrates of the nonspecific pathogen Erwinia carotovora. Plant Physiol. 126, 849–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busam, G., Junghanns, K.T., Kneusel, R.E., Kassemeyer, H.H., and Matern, U. (1997). Characterization and expression of caffeoyl-coenzyme A 3-O-methyltransferase proposed for the induced resistance response of Vitis vinifera L. Plant Physiol. 115, 1039–1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capelli, N., Diogon, T., Greppin, H., and Simon, P. (1997). Isolation and characterization of a cDNA clone encoding an osmotin-like protein from Arabidopsis thaliana. Gene 191, 51–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter, C., Graham, R.A., and Thornburg, R.W. (1998). Arabidopsis thaliana contains a large family of germin-like proteins: Characterization of cDNA and genomic sequences encoding 12 unique family members. Plant Mol. Biol. 38, 929–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W., et al. (2002). Expression profile matrix of Arabidopsis transcription factor genes suggests their putative functions in response to environmental stresses. Plant Cell 14, 559–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong, Y.H., Chang, H.S., Gupta, R., Wang, X., Zhu, T., and Luan, S. (2002). Transcriptional profiling reveals novel interactions between wounding, pathogen, abiotic stress, and hormonal re-sponses in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 129, 661–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chye, M.L., and Cheung, K.Y. (1995). β-1,3-Glucanase is highly expressed in laticifers of Hevea brasiliensis. Plant Mol. Biol. 29, 397–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, G.D., and Chen, T.H. (1993). Sequence of a poplar bark storage protein gene. Plant Physiol. 102, 1347–1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittrich, H., and Kutchan, T.M. (1991). Molecular cloning, expression, and induction of berberine bridge enzyme, an enzyme essential to the formation of benzophenanthridine alkaloids in the response of plants to pathogenic attack. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88, 9969–9973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, C., and Turner, J.G. (2001). The Arabidopsis mutant cev1 has constitutively active jasmonate and ethylene signal pathways and enhanced resistance to pathogens. Plant Cell 13, 1025–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feys, B.J., and Parker, J.E. (2000). Interplay of signaling pathways in plant disease resistance. Trends Genet. 16, 449–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazebrook, J. (2001). Genes controlling expression of defense responses in Arabidopsis: 2001 status. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 4, 301–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkier, B.A. (1999). Glucosinolates. In Naturally Occurring Glycosides: Chemistry, Distribution, and Biological Properties, R. Ikan, ed (New York: John Wiley & Sons), pp. 193–223.

- Hoffman, T., Schmidt, J.S., Zheng, X., and Bent, A. (1999). Isolation of ethylene-insensitive soybean mutants that are altered in pathogen susceptibility and gene-for-gene disease resistance. Plant Physiol. 119, 935–949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intapruk, C., Takano, M., and Shinmyo, A. (1994). Nucleotide sequence of a new cDNA for peroxidase from Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. 104, 285–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justesen, A.F., Jespersen, H.M., and Welinder, K.G. (1998). Analysis of two incompletely spliced Arabidopsis cDNAs encoding novel types of peroxidase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1443, 149–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiedrowski, S., Kawalleck, P., Hahlbrock, K., Somssich, I.E., and Dangl, J.L. (1992). Rapid activation of a novel plant defense gene is strictly dependent on the Arabidopsis RPM1 disease resistance locus. EMBO J. 11, 4677–4684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoester, M., van Loon, L.C., van den Heuvel, J., Henning, J., Bol, J.F., and Linthorst, H.J.M. (1998). Ethylene-insensitive tobacco lacks nonhost resistance against soil-borne fungi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 1933–1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J., Klessig, D.F., and Nurnberger, T. (2001). A harpin binding site in tobacco plasma membranes mediates activation of the pathogenesis-related gene HIN1 independent of extracellular calcium but dependent on mitogen-activated protein kinase activity. Plant Cell 13, 1079–1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConn, M., Creelman, R.A., Bell, E., Mullet, J.E., and Browse, J. (1997). Jasmonate is essential for insect defense in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 5473–5477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell, J.M., and Dangl, J.L. (2000). Signal transduction in the plant immune response. Trends Biochem. Sci. 25, 79–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman-Setterblad, C., Vidal, S., and Palva, E.T. (2000). Interacting signal pathways control defense gene expression in Arabidopsis in response to cell wall-degrading enzymes from Erwinia carotovora. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 13, 430–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell, P.J., Calvert, C., Atzorn, R., Wasternack, C., Leyser, H.M.O., and Bowles, D.J. (1996). Ethylene as a signal mediating the wound response of tomato plants. Science 274, 1914–1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtake, Y., Takahashi, T., and Komeda, Y. (2000). Salicylic acid induces the expression of a number of receptor-like kinase genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 41, 1038–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onate-Sanchez, L., and Singh, K.B. (2002). Identification of Arabidopsis ethylene-responsive element binding factors with distinct induction kinetics after pathogen infection. Plant Physiol. 128, 1313–1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overmyer, K., Tuominen, H., Kettunen, R., Betz, C., Langebartels, C., Sandermann, H., Jr., and Kangasjarvi, J. (2000). Ozone-sensitive Arabidopsis rcd1 mutant reveals opposite roles for ethylene and jasmonate signaling pathways in regulating superoxide-dependent cell death. Plant Cell 12, 1849–1862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penninckx, I.A.M.A., Eggermont, K., Terras, F.R.G., Thomma, B.P.H.J., De Samblanx, G.W., Buchala, A., Metraux, J.-P., Manners, J.M., and Broekaert, W.F. (1996). Pathogen-induced systemic activation of a plant defensin gene in Arabidopsis follows a salicylic acid-independent pathway. Plant Cell 8, 2309–2323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penninckx, I.A.M.A., Thomma, B.P.H.J., Buchala, A., Metraux, J.-P., and Broekaert, W.F. (1998). Concomitant activation of jasmonate and ethylene response pathways is required for induction of a plant defensin. Plant Cell 10, 2103–2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, M., et al. (2000). Arabidopsis MAP kinase 4 negatively regulates systemic acquired resistance. Cell 103, 1111–1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse, C.M., van Wees, S.C., Hoffland, E., van Pelt, J.A., and van Loon, L.C. (1996). Systemic resistance in Arabidopsis induced by biocontrol bacteria is independent of salicylic acid accumulation and pathogenesis-related gene expression. Plant Cell 8, 1225–1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse, C.M.J., van Wees, S.C.M., van Pelt, J.A., Knoester, M., Laan, R., Gerrits, H., Weisbeek, P.J., and van Loon, L.C. (1998). A novel signaling pathway controlling induced systemic resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 10, 1571–1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponce de Leon, I., Sanz, A., Hamberg, M., and Castresana, C. (2002). Involvement of the Arabidopsis alpha-DOX1 fatty acid dioxygenase in protection against oxidative stress and cell death. Plant J. 29, 61–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao, M.V., and Davis, K.R. (1999). Ozone-induced cell death occurs via two distinct mechanisms in Arabidopsis: The role of salicylic acid. Plant J. 17, 603–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao, M.V., Lee, H., Creelman, R.A., Mullet, J.E., and Davis, K.R. (2000). Jasmonic acid signaling modulates ozone-induced hypersensitive cell death. Plant Cell 12, 1633–1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rask, L., Andreasson, E., Ekbom, B., Eriksson, S., Pontoppidan, B., and Meijer, J. (2000). Myrosinase: Gene family evolution and herbivore defense in Brassicaceae. Plant Mol. Biol. 42, 93–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen, U., Bojsen, K., and Collinge, D.B. (1992). Cloning and characterization of a pathogen-induced chitinase in Brassica napus. Plant Mol. Biol. 20, 277–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reymond, P., Weber, H., Damond, M., and Farmer, E.E. (2000). Differential gene expression in response to mechanical wounding and insect feeding in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 12, 707–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojo, E., Leon, J., and Sanchez-Serrano, J.J. (1999). Cross-talk between wound signaling pathways determines local versus systemic gene expression in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 20, 135–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roper, J.M., and Smith, A.G. (1997). Molecular localisation of ferrochelatase in higher plant chloroplasts. Eur. J. Biochem. 246, 32–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samac, D.A., and Shah, D.M. (1994). Effect of chitinase antisense RNA expression on disease susceptibility of Arabidopsis plants. Plant Mol. Biol. 25, 587–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenk, P.M., Kazan, K., Wilson, I., Anderson, J.P., Richmond, T., Somerville, S.C., and Manners, J.M. (2000). Coordinated plant defense responses in Arabidopsis revealed by microarray analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 11655–11660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solano, R., Stepanova, A., Chao, Q.M., and Ecker, J.R. (1998). Nuclear events in ethylene signaling: A transcriptional cascade mediated by ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE3 and ETHYLENE-RESPONSE-FACTOR1. Genes Dev. 12, 3703–3714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staswick, P.E., Yuen, G.Y., and Lehman, C.C. (1998). Jasmonate signaling mutants of Arabidopsis are susceptible to the soil fungus Pythium irregulare. Plant J. 15, 747–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturm, A., and Chrispeels, M.J. (1990). cDNA cloning of carrot extracellular beta-fructosidase and its expression in response to wounding and bacterial infection. Plant Cell 2, 1107–1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue, M., Ishihara, A., and Iwamura, H. (2000). Purification and characterization of a hydroxamic acid glucoside beta-glucosidase from wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) seedlings. Planta 210, 432–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terras, F.R., Torrekens, S., Van Leuven, F., Osborn, R.W., Vanderleyden, J., Cammue, B.P., and Broekaert, W.F. (1993). A new family of basic cysteine-rich plant antifungal proteins from Brassicaceae species. FEBS Lett. 316, 233–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomma, B.P.H.J., Eggermont, K., Broekaert, W.F., and Cammue, B.P.A. (2000). Disease development of several fungi on Arabidopsis can be reduced by treatment with methyl jasmonate. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 38, 421–427. [Google Scholar]

- Thomma, B.P.H.J., Eggermont, K., Penninckx, I.A.M.A., Mauch-Mani, B., Vogelsang, R., Cammue, B.P.A., and Broekaert, W.F. (1998). Separate jasmonate-dependent and salicylate-dependent defense-response pathways in Arabidopsis are essential for resistance to distinct microbial pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 15107–15111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomma, B.P.H.J., Eggermont, K., Tierens, K.F.M.-J., and Broekaert, W.F. (1999). Requirement of functional Ethylene-Insensitive 2 gene for efficient resistance of Arabidopsis to infection by Botrytis cinerea. Plant Physiol. 121, 1093–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomma, B.P.H.J., Penninckx, I.A.M.A., Broekaert, W.F., and Cammue, B.P.A. (2001). The complexity of disease signaling in Arabidopsis. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 13, 63–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truesdell, G.M., and Dickman, M.B. (1997). Isolation of pathogen/stress-inducible cDNAs from alfalfa by mRNA differential display. Plant Mol. Biol. 33, 737–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner, J.G., Ellis, C., and Devoto, A. (2002). The jasmonate signal pathway. Plant Cell 14 (suppl.), S153.–S164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uknes, S., Mauch-Mani, B., Moyer, M., Potter, S., Williams, S., Dincher, S., Chandler, D., Slusarenko, A., Ward, E., and Ryals, J. (1992). Acquired resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 4, 645–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Fits, L., and Memelink, J. (2000). ORCA3, a jasmonate-responsive transcriptional regulator of plant primary and secondary metabolism. Science 289, 295–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Fits, L., and Memelink, J. (2001). The jasmonate-inducible AP2/ERF-domain transcription factor ORCA3 activates gene expression via interaction with a jasmonate-responsive promoter element. Plant J. 25, 43–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kan, J.A., Joosten, M.H., Wagemakers, C.A., van den Berg-Velthuis, G.C., and de Wit, P.J. (1992). Differential accumulation of mRNAs encoding extracellular and intracellular PR proteins in tomato induced by virulent and avirulent races of Cladosporium fulvum. Plant Mol. Biol. 20, 513–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayan, P., Shockey, J., Levesque, C.A., Cook, R.J., and Browse, J. (1998). A role for jasmonate in pathogen defense of Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 7209–7214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.L., Li, H., and Ecker, J.R. (2002). Ethylene biosynthesis and signaling networks. Plant Cell 14 (suppl.), S131.–S151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welle, R., Schroder, G., Schiltz, E., Grisebach, H., and Schroder, J. (1991). Induced plant responses to pathogen attack: Analysis and heterologous expression of the key enzyme in the biosynthesis of phytoalexins in soybean (Glycine max L. Merr. cv. Harosoy 63). Eur. J. Biochem. 196, 423–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y., Chang, P.F., Liu, D., Narasimhan, M.L., Raghothama, K.G., Hasegawa, P.M., and Bressan, R.A. (1994). Plant defense genes are synergically induced by ethylene and methyl jasmonate. Plant Cell 6, 1077–1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.