Abstract

Quality control is an important aspect of a study because the quality of data collected provides a foundation for the conclusions drawn from the study. For studies that include interviews, establishing quality control for interviews is critical in ascertaining whether interviews are conducted according to protocol. Despite the importance of quality control for interviews, few studies adequately document the quality control procedures used during data collection. This article reviews quality control for interviews and describes methods and results of quality control for interviews from two of our studies regarding the accuracy of children's dietary recalls; the focus is on quality control regarding interviewer performance during the interview, and examples are provided from studies with children. For our two studies, every interview was audio recorded and transcribed. The audio recording and typed transcript from one interview conducted by each research dietitian either weekly or daily were randomly selected and reviewed by another research dietitian, who completed a standardized quality control for interviews checklist. Major strengths of the methods of quality control for interviews in our two studies include: (a) interviews obtained for data collection were randomly selected for quality control for interviews, and (b) quality control for interviews was assessed on a regular basis throughout data collection. The methods of quality control for interviews described may help researchers design appropriate methods of quality control for interviews for future studies.

Quality control is an important aspect of a study because the quality of data collected provides a foundation for the conclusions drawn from the study (1). For studies that include interviews, establishing quality control for interviews is critical in ascertaining whether interviews are conducted according to protocol. Nutrition studies often rely on more than one interviewer to conduct dietary recalls. Common sense dictates that if all interviews are not conducted according to protocol, then the information that one interviewer obtains from a subject may be different from the information another interviewer might have obtained from the same subject. Despite the importance of quality control for interviews, few studies have adequately documented the quality control procedures used during data collection (2). The purposes of this article are to review quality control for interviews in general and to describe the methods and results of quality control for interviews from two of our studies regarding the accuracy of children's dietary recalls. Although quality control should be performed from interviewer training to data entry of dietary recalls, this article discusses methods regarding interviewer performance during the interview only (not data entry). Furthermore, although quality control for interviews is vital to studies involving subjects in any age group, this article uses examples from studies with children because children have been the focus of our research.

GENERAL REVIEW OF QUALITY CONTROL FOR INTERVIEWS

One method of assessing quality control for interviews is to ask 10% of subjects to provide duplicate dietary recalls to different interviewers and then to compare the nutrient profiles of each individual subject's two recalls, as was done by Frank and colleagues (3). Duplicate dietary recalls raise several concerns that decrease their appeal and usefulness. First, even if both interviewers conduct the interview according to protocol, the subject may report different information in the back-to-back interviews; this would falsely imply that the interviewer(s) did not follow the interview protocol. Second, the subject is burdened with having to provide two dietary recalls in a row. Third, subjects report foods, not nutrients, so comparing the nutrient profiles of the two duplicate dietary recalls may yield similar results for some nutrients but not others because a discrepancy between the two recalls may be similar for certain nutrients but different for others.

The Continuing Survey of Food Intakes by Individuals (CSFII), 1994-1996 (4) and the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994 (NHANES III) (5) are examples of major nationwide studies that obtained 24-hour dietary recalls from various age groups including children. For the CSFII 1994-1996 (4), several procedures were used to monitor the quality of the data that interviewers collected, including audio recording and observation. For audio recording, the supervisor identified three interviews to be taped per interviewer for each survey year. After the interview was completed, the audio recording was mailed to the supervisor, who evaluated each interviewer's performance and provided feedback. In addition, a random sample of 10% of recalls was audio recorded and reviewed to monitor interviewer performance. Although some interviews were observed, it is unclear how many interviews were observed each year. For NHANES III (5), interviewers were monitored either in the field by observations of interviews in progress or by reviews of audio-recorded interviews; however, it is unclear how many interviews were observed or audio recorded or if this was done for interviews used for data collection. In January 2002, the CSFII merged with NHANES (6). Although the quality control for interviews procedures for the integrated CSFII—NHANES have not yet been published, 5% of interviews conducted by each interviewer are either audio recorded and reviewed by a home office staff member (in-person interviewers) or observed by a supervisor (telephone interviewers) (personal communication, Betty Perloff, United States Department of Agriculture, Food Surveys Research Group, 12/18/03). In summary, for CSFII 1994-1996, NHANES III, and the integrated CSFII—NHANES, interviewers knew in advance which interviews would be assessed for quality control for interviews. This advance knowledge is of concern because interviewers may alter their behaviors when they know interviews are being assessed for quality control.

In large studies for which children provided 24-hour dietary recalls, such as the Bogalusa Heart Study (7), the Dietary Intervention Study in Children (8), and the Child and Adolescent Trial for Cardiovascular Health (9), quality control for interviews procedures were mentioned briefly or readers were referred to other publications for details. For the Bogalusa Heart Study and the Dietary Intervention Study in Children, duplicate 24-hour dietary recalls were used for quality control purposes (7, 8). For the Child and Adolescent Trial for Cardiovascular Health, each interviewer was audio recorded at least once during the study while obtaining a 24-hour dietary recall, then senior nutritionists rated the interviewer's performance using standard criteria from a checklist and gave the interviewer immediate feedback (9). Both methods of quality control for interviews used in these three studies are prone to the limitations mentioned previously.

According to a recent Medline search by McPherson and colleagues (10) and our own review of publications since 1945, there are 21 validation studies (contained in 20 publications) that validated elementary school children's dietary recalls that were obtained without parental assistance and used methods that involved neither self-reports nor parental reports (11-30). Only four of the 21 studies mentioned quality control for interviews procedures (11,14,15,29); three of these four were conducted by our group. For our study regarding the accuracy and consistency of fourth-graders' school breakfast and school lunch recalls (11), inter-interviewer reliability was assessed by having research dietitians observe an interview being conducted by another research dietitian and complete duplicate interview forms according to what was heard. In addition, the principal investigator (PI) randomly selected and reviewed 5% of each interviewer's transcripts and audiotapes. The methods of quality control for interviews used in our group's other two studies (14,15) are described in detail later in this article. Todd and Kretsch (29) briefly described the quality control for interviews procedures for their study regarding the accuracy of self-reported dietary recalls of immigrant and refugee children by stating that a supervisory dietitian “unobtrusively observed interviews to ensure consistency of procedures”; however, the number of interviews observed is unclear. A review by Contento and colleagues (31) cited 16 articles that used 24-hour dietary recalls to evaluate nutrition education interventions with children (32-47), but only five of the 16 articles mentioned quality control for interviews (32-34,38,45); furthermore, in these five articles, quality control for interviews was only briefly discussed, methods of assessing quality control for interviews were generally unclear, and results of quality control for interviews were not reported.

According to Fowler, the best way for a supervisor to monitor whether interviewers conduct interviews according to protocol is to observe them; this can be done by sitting in on interviews or audio recording the interviews (48). However, Whitney (1) commented that a supervisor's presence at interviews is not the best way to assess interviewer performance because it may alter the behavior of the interviewer and/or the subject. In contrast, audio recording every interview allows for any interview to be selected randomly for quality control review after the interview has been conducted. This is important because interviewers do not know in advance which interviews will be assessed, and are less likely to conduct the interview differently because they know it is being monitored. Billiet and Loosveldt (49) and Fowler and Mangione (50) reported that audio recording interviews decreased the amount of interviewer-related error in surveys. Furthermore, Fowler and Mangione commented that audio recording the interviews does not seem to have a negative effect on response rates or subjects' reports of how they felt about interviews (50).

The International Study of Macro- and Micronutrients and Blood Pressure was a multicountry study that investigated the relationship between multiple nutrients and blood pressure among adults (51). Data collection for the International Study of Macro- and Micronutrients and Blood Pressure included 24-hour dietary recalls; every interview was audio recorded, and randomly selected interviews were reviewed for quality control for interviews. The International Study of Macro- and Micronutrients and Blood Pressure researchers reported that “An advantage of prompt and ongoing local evaluation of tape recordings by site nutritionists was that it gave rapid feedback to the dietary interviewers. It thereby served as a practical tool for maintenance and enhancement of quality data collection.”

METHODS OF QUALITY CONTROL FOR INTERVIEWS USED IN STUDIES 1 AND 2

Background of Studies 1 and 2

The methods of quality control for interviews described here were used in two studies (study 1, study 2) regarding the accuracy of fourth-grade children's dietary recalls (14,15). The Institutional Review Board approved both studies. Child assent and parental consent were both obtained before data collection for each study. For both studies, randomly selected children from up to 11 public schools in one school district were observed eating school meals (breakfast, lunch) and were later interviewed regarding intake. Children were interviewed individually by trained research dietitians in private locations or over the telephone (depending on the study). Interviewers for each study followed a written, multiple-pass protocol similar to that used by the Nutrition Data System for Research (version 4.03, 2000, Nutrition Coordinating Center, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis), but interviewers wrote information on a paper form rather than entering it into a computer while the interviews were conducted.

For both studies, interviewer training consisted of reading interview protocols, role playing, and conducting practice interviews with children. Practice interviews with children were audio recorded and usually transcribed. For data collection, interviewers audio recorded and transcribed every interview. During training and data collection, the interviewer usually typed her own transcripts; this method was preferred because it provided the interviewer with immediate feedback. After interviewer training for study 1, the need was recognized for a standardized method of evaluating the transcripts reviewed; this led to the development of a quality control for interviews checklist. For both studies 1 and 2, the PI and each interviewer had to agree that, based on training and practice interviews, interview quality had reached an acceptable level and thus each interviewer was ready to begin data collection.

Quality Control Procedures for the Two Studies

Over the course of the two studies, the methods of quality control for interviews evolved to meet the needs of the different studies. For both studies, quality control for interviews was assessed regularly throughout data collection (weekly or daily) to ascertain whether interviewers were adequately following protocol (thereby indicating that acceptable quality was maintained). A quality control for interviews checklist was completed and returned to the interviewer the week after the interview to provide the interviewer with prompt feedback. Interviewers participated in the process of quality control for interviews by completing quality control for interviews checklists on interviews conducted by other research dietitians.

All methods of quality control for interviews must have actionable rules to apply when the process suggests a decrease in quality below the acceptable level. Because some items on our quality control for interviews checklists were deemed more important than others, we classified all errors as either fatal, moderate, or minor. Fatal errors were errors that jeopardized the methodological aspect being tested. For example, a fatal error in study 1 would be if, during a reverse-order interview for study 1 (refer to forthcoming details regarding study 1), the interviewer prompted the child to begin with what she or he ate after getting up the day before instead of before going to bed the previous night. Moderate errors were items that could affect the quality of the interview. An example of a moderate error is failing to ask “What kind of. . .” and “How much of. . .” for foods that were reported added to other foods (eg, the child reported adding salad dressing to salad, but the interviewer did not ask the child what kind of, and how much, salad dressing was added to the salad). Minor errors were items regarding how the interviewer conducted the interview. An example of a minor error is saying “okay” except where written in the protocol. For both studies, the PI evaluated each interview assessed for quality control for interviews, considered the number and level of errors, and decided whether the interview would be used for data analysis. If an interview contained a fatal error, it would have been dropped from data analysis, and the interviewer would have received additional training on that portion of the protocol. If an interview contained several moderate errors and/or minor errors, it was reviewed more thoroughly and possibly dropped.

Study 1

Study 1 was conducted at 11 schools during the 2000-2001 school year to determine whether the accuracy of school breakfast and school lunch portions of children's 24-hour dietary recalls was better when children were prompted to report meals and snacks in reverse order (ie, “Going backwards through yesterday. . .”) compared with forward order (ie, “Going forwards through yesterday. . .”). A detailed description of the interview protocol and results regarding recall accuracy are reported elsewhere (14).

For study 1, staffing allowed for 12 to 32 interviews to be conducted each week, with one to three interviews conducted per interviewer each morning (Tuesday through Friday) depending on how many children were observed eating school meals (breakfast, lunch) on the previous day. Throughout data collection, quality control for interviews was assessed weekly for each interviewer. On the first work day each week, each research dietitian checked the quality control for interviews schedule to see which interviewer she was assigned to check for the previous week and randomly selected an interview conducted by that interviewer. The audio recording, transcript typed by the interviewer, and interview form from the randomly selected interview were reviewed, and a quality control for interviews checklist was completed. The typed transcript was compared with the audio recording to ascertain that it was typed verbatim. The reviewer noted any errors reflecting what she heard on the audio recording and wrote comments regarding deviance from the interview protocol directly on the transcript; the reviewer also corrected any errors on the interview form in a different color ink and dated and initialed the changes made. The completed quality control for interviews checklist and transcript were routed to the interviewer and PI, who each reviewed them and initialed the checklist. The quality control for interviews checklist for study 1 contained 53 items regarding all phases of the interview, the interview form, and the typed transcript. Response options for each item were “adequate” and “needs improvement.” There was also a space for comments; “not applicable” was written in the comment section if an item did not apply to that particular interview. For example, the reviewer would write “not applicable” for the item “Did not ask any details about water” if the child did not report water during the interview.

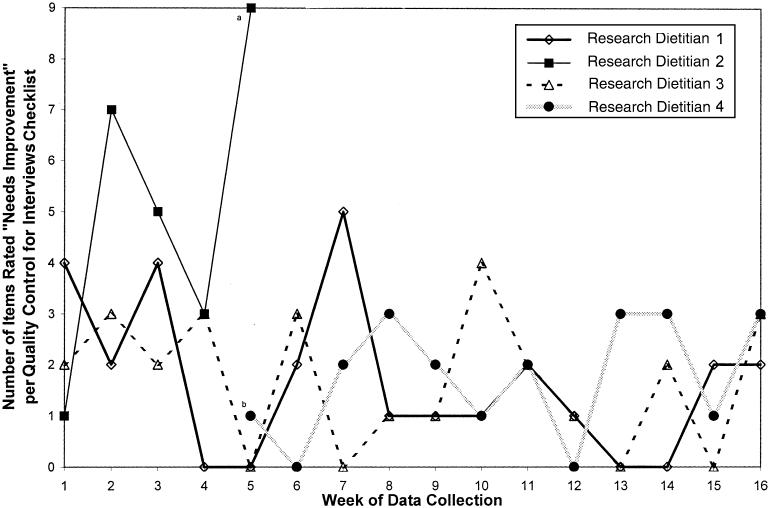

For study 1, 242 interviews were completed by four interviewers (research dietitian 1, research dietitian 2, research dietitian 3, research dietitian 4). Forty-nine of the 242 interviews (20%) were reviewed for quality control for interviews. After excluding items rated not applicable, 95% of items (2,081 of 2,181) were rated adequate and 5% of items (100 of 2,181) were rated needs improvement across all 49 quality control for interviews checklists. Of the 100 items rated needs improvement, items causing the most problems were failing to type transcripts verbatim (n=14); failing to ask, “What kind of. . .” and “How much of. . .” for foods that were reported added to other foods (n=8); failing to write AM or PM on the interview form (n=7); talking too fast (n=6); and failing to ask, “Was that morning or evening?” if the child did not give an indication as to time of day (n=6). The Table summarizes quality control for interviews results by interviewer and across interviewers for study 1. Items causing the most problems included minor and moderate errors, but there were no fatal errors and no interviews had to be dropped. A catchall item (“Did not follow interview protocol”) was included on the quality control for interviews checklists to cover deviations from the protocol not specifically mentioned elsewhere on the checklist. However, on reviewing the quality control for interviews checklists from studies 1 and 2 for this article, we noticed that reviewers sometimes marked needs improvement for the catchall item in addition to a specific item on the checklist when both regarded a single deviation from protocol. Therefore, each quality control for interviews checklist was reviewed again by the PI and another team member to delete any “double dings.” Figure 1 shows the number of items rated needs improvement for study 1 per quality control for interviews checklist and interviewer by week of data collection. The number of items rated needs improvement per checklist ranged from zero to five for research dietitian 1, one to nine for research dietitian 2, zero to four for research dietitian 3, and zero to three for research dietitian 4. For each research dietitian, the number of items rated needs improvement on a checklist often markedly decreased after a checklist with a high number of items rated needs improvement. This suggests that the constant and prompt feedback from the quality control for interviews checklists kept the interviewers alert and helped to prevent a gradual deterioration in performance so that an acceptable level of quality could be maintained throughout data collection. Results from quality control for interviews for study 1 showed that research dietitian 1, research dietitian 3, and research dietitian 4 adequately followed the protocols for completing the interviews throughout data collection. Research dietitian 2 was being retrained to reduce the number of items rated needs improvement on quality control for interviews checklists completed on interviews she conducted when she suddenly resigned. After her resignation, each interview she conducted was audited to ensure that it was acceptable for use in data analysis; however, no interview had to be dropped.

Figure 1.

Study 1: Number of items rated “needs improvement” per quality control for interviews checklist and interviewer by week of data collection. (aResearch Dietitian 2 was being retrained when she suddenly resigned; therefore, she did not continue to conduct interviews. bResearch Dietitian 4 was hired later and did not begin conducting interviews for data collection until week 5.)

Study 2

Study 2 was conducted at 10 schools during the 2001-2002 school year to determine if interviews conducted in person yielded more accurate dietary recalls than interviews conducted by telephone. Two research dietitians conducted interviews for study 2; research dietitian 1 conducted interviews on the first nine evenings, and research dietitian 2 conducted interviews for the remainder of the study. A detailed description of the interview protocol and results regarding recall accuracy are reported elsewhere (15).

For study 2, staffing allowed for eight to 24 interviews to be conducted each week, with two to six interviews conducted each evening (Monday through Thursday), depending on how many children were observed eating school meals that day. In a manner very similar to that of study 1 but on a more frequent basis, quality control for interviews was assessed for study 2 on one interview each day throughout data collection. The quality control for interviews checklist contained 56 items regarding all phases of the interview and interview form; the checklist had an additional four items regarding typing the transcript, but this is not reported as quality control for interviews because a research dietitian other than the interviewer may have typed the transcript. (A research dietitian could not conduct quality control for interviews on a transcript she typed.) Response options for each item were “adequate,” “needs improvement,” and “not applicable.” Each item also had a space for comments.

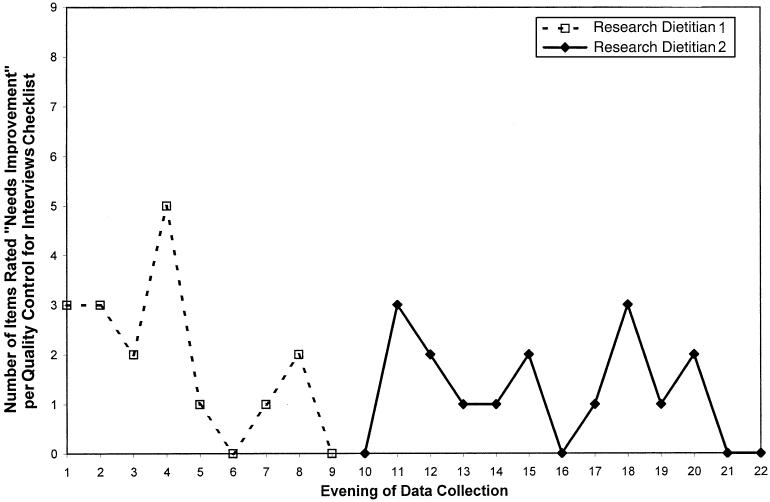

For study 2, 69 interviews were completed by two interviewers (research dietitian 1, research dietitian 2); 22 of the 69 interviews (32%) were reviewed for quality control for interviews purposes. After excluding items rated not applicable, 97% of items (937 of 970) were rated adequate and 3% (33 of 970) were rated needs improvement across all 22 quality control for interviews checklists. Of the 33 items rated needs improvement, items causing the most problems were failing to ask, “Was that this morning or tonight?” if more than 12 hours had passed since the reported time of a meal or snack (n=4), and failing to write AM or PM on the interview form where appropriate (n=3). The Table summarizes quality control for interviews results by interviewer and across interviewers for study 2. As with study 1, items causing the most problems in study 2 included both minor and moderate errors, but there were no fatal errors and no interviews had to be dropped. Figure 2 shows the number of items rated needs improvement for study 2 per quality control for interviews checklist and interviewer by evening of data collection. The number of items rated needs improvement per quality control for interviews checklist ranged from zero to five for research dietitian 1 and zero to three for research dietitian 2. Again, for both research dietitians, the number of items rated needs improvement on a checklist often markedly decreased after a checklist with a high number of items rated needs improvement. Results for quality control for interviews for study 2 indicated that both interviewers adequately followed the interview protocol throughout data collection.

Figure 2.

Study 2: Number of items rated “needs improvement” per quality control for interviews checklist and interviewer by evening of data collection.

DISCUSSION

There are several strengths of the methods of quality control for interviews used in studies 1 and 2. First, every interview was audio recorded. This allowed any interview to be randomly selected for quality control for interviews, and it encouraged interviewers to follow the interview protocol because they knew that any interview could be randomly selected and checked for quality control for interviews purposes. Furthermore, audio recording each interview was necessary to type the transcript; typing the transcript made the typist (who was usually the research dietitian who conducted the interview) aware of any deviations from the protocol that were made during the interview. Second, quality control for interviews was assessed throughout data collection instead of only during training or only after data collection ended. Quality control for interviews checklists were completed no later than the Friday of the week after the interview so that feedback could be provided to each interviewer in a timely manner; this allowed interviewers to correct their technique before conducting a large number of additional interviews and thus helped to prevent a gradual deterioration in performance to unacceptable levels. Third, children were not burdened with having to provide duplicate dietary recalls in which they may have reported different items or amounts to different interviewers, which could falsely imply deviance on the interviewer's part from the interview protocol. Fourth, interviews conducted for data collection were assessed for quality control for interviews as opposed to conducting interviews solely for purposes of assessing quality control for interviews. Fifth, our methods of quality control for interviews did not include a supervisor observing the interview to assess quality control for interviews; having a supervisor observe an interview for quality control for interviews could alter the interviewer's performance because she would know she was being evaluated, and could also change the dynamics between the child and interviewer. Finally, interviewer performance within each study was assessed in a standardized manner (ie, using a quality control for interviews checklist).

A limitation of the methods of quality control for interviews for studies 1 and 2 is that nonverbal communication, which may be important for in-person interviews, could not be assessed. In addition, an oversight (mentioned previously) made by our team when developing the quality control for interviews checklists was the incorporation of duplicate items. When developing quality control for interviews checklists for use in future studies, researchers should avoid including duplicate items.

Quality control for interviews may be more commonly overlooked when automated protocols are used to obtain recalls because researchers may feel that the automated protocol itself ascertains adherence to the interview protocol.

The methods of quality control for interviews used for studies 1 and 2 are appropriate for use in various types of studies that obtain dietary recalls. Quality control for interviews checklists can be modified according to the specific interview protocols used. These methods could be applied to automated (ie, computerized) interview protocols (such as Nutrition Data System for Research) as well; quality control for interviews checklists could be created containing items such as entering information as reported by the subject, avoiding the use of additional prompts not in the interview protocol, and so on. Quality control for interviews may be more commonly overlooked when automated protocols are used to obtain recalls because researchers may feel that the automated protocol itself ascertains adherence to the interview protocol. However, even when using automated protocols, quality control for interviews is necessary to monitor whether interviewers followed the interview protocol (ie, used prompts or probes appropriately and recorded dietary intake exactly as reported by subjects during the interview). The fact that interviewers are trained and/or certified is often mentioned in publications (eg, references 22, 36, 42, and 52). Although training and certification of interviewers are important, this is generally done before data collection; thus, it does not ensure that interviewers followed the interview protocol throughout data collection. When designing studies that use 24-hour dietary recalls, it is imperative to assess quality control for interviews during training (to ascertain acceptable quality for data collection to begin) as well as regularly throughout data collection (to ascertain acceptable maintenance of quality throughout the study). As mentioned previously, although this article only discusses quality control for interviews for studies done with children, the same principles and standards should be applied to studies with any age group.

In summary, quality control for interviews should be an integral part of any study obtaining dietary recalls to ascertain whether interviews are conducted according to protocol. The methods of quality control for interviews used during our two studies may help researchers design appropriate methods of quality control for interviews for future studies.

CONCLUSIONS

When conducting a study that includes dietary recalls, perform quality control for interviews during training and practice before data collection as well as throughout data collection. Develop a quality control for interviews checklist based on the interview protocol but avoid duplicate items.

Create guidelines from the quality control for interviews checklist for actions to be taken if an interviewer does not follow the interview protocol (ie, team discussion, retraining, termination).

Set guidelines to determine whether an interview will or will not be used for data analysis.

Assess quality control for interviews only on randomly selected interviews conducted for actual data collection to avoid the problem of the interviewer knowing before conducting interviews which interviews will be used for quality control for interviews; this can be accomplished by audio recording all interviews.

Discuss methods of, and results of, quality control for interviews when publishing or presenting results of studies that use dietary recalls.

When reading publications or attending oral or poster presentations that report results of studies that use dietary recalls, consider the methods of, and results of, quality control for interviews when drawing conclusions about the strength of the study's results. If possible, ask questions when the methods of, or results of, quality control for interviews are not described or are unclear.

Table.

Summary of results for QCIa by interviewer and across interviewers for study 1 and study 2

| Study 1b |

Study 2c |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Research Dietitian 1 | Research Dietitian 2 | Research Dietitian 3 | Research Dietitian 4 | Total (mean) | Research Dietitian 1 | Research Dietitian 2 | Total (mean) | |

| Number of interviews conducted | 81 | 30 | 72 | 59 | 242 | 28 | 41 | 69 |

| Number of interviews for which QCI was evaluated | 16 | 5 | 16 | 12 | 49 | 9 | 13 | 22 |

| Number of items rated needs improvement across all QCI checklistsd | 27 | 25 | 27 | 21 | 100 | 17 | 16 | 33 |

| Mean number of items rated needs improvement per QCI checkliste | 1.7 | 5.0 | 1.7 | 1.8 | (2.0) | 1.9 | 1.2 | (1.5) |

| Median number of items rated needs improvement per QCI checklistf | 1.5 | 5.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | (2.0) | 2.0 | 1.0 | (1.0) |

| Number of QCI checklists with two or fewer items rated needs improvement | 13 | 1 | 11 | 8 | 33 | 6 | 11 | 17 |

QCI=quality control for interviews.

Four research dietitians (Research Dietitians 1, 2, 3, and 4) conducted interviews.

Two research dietitians (Research Dietitians 1 and 2) conducted interviews.

For study 1, the QCI checklist contained 53 items. For study 2, the QCI checklist contained 56 items. On checklists for both studies, any item could have been rated not applicable for an individual interview.

The mean was calculated by dividing the total number of items rated needs improvement across all QCI checklists by the number of QCI checklists. For example, for study 1, Research Dietitian 1 had 27 items rated needs improvement across 16 QCI checklists, so the mean number of items rated needs improvement was 27÷16=1.7.

The median was calculated by ordering the number of items rated needs improvement from lowest to highest and finding the middle number (if there was no middle number, the arithmetic mean of the two middle numbers was used). For example, for study 1, for Research Dietitian 2, the number of items rated needs improvement per checklist in order from lowest to highest was one, three, five, seven, and nine; therefore, the median number of items rated needs improvement per checklist was five (because there are two values below five and two values above five).

Footnotes

This research was supported by R01 grant HL 63189 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health; the Principal Investigator was Suzanne Domel Baxter, PhD, RD, FADA.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the children, faculty, and staff of Blythe, Goshen, Gracewood, Hephzibah, Lake Forest Hills, McBean, Monte Sano, National Hills, Rollins, Willis Foreman, and Windsor Spring Elementary Schools, and the Richmond County Board of Education in Georgia for allowing data to be collected.

References

- 1.Whitney CW, Lind BK, Wahl PW. Quality assurance and quality control in longitudinal studies. Epidemiol Rev. 1998;20:71–80. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a017973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edwards S, Slattery ML, Mori M, Berry TD, Caan BJ, Palmer P, Potter JD. Objective system for interviewer performance evaluation for use in epidemiological studies. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;140:1020–1028. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frank GC, Hollatz AT, Webber LS, Berenson GS. Effect of interviewer recording practices on nutrient intake—Bogalusa Heart Study. J Am Diet Assoc. 1984;84:1432–1439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tippett KS, Cypel YS, editors. Design and Operation: The Continuing Survey of Food Intakes by Individuals and the Diet and Health Knowledge Survey, 1994-96. No. 96-1; . US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Department of Health and Human Services . Plan and Operation of the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-94. National Center for Health Statistics, Vital and Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 1994. DHHS Publication No. (PHS) 94-1308. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Food Surveys Research Group Frequently Asked Questions—HHS-USDA Dietary Survey Integration. Available at: http://www.barc.usda.gov/bhnrc/foodsurvey/integrationfaq.html. Accessed June 24, 2002.

- 7.Frank GC, Berenson GS, Webber LS. Dietary studies and the relationship of diet to cardiovascular disease risk factor variables in 10-year old children—The Bogalusa Heart Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 1978;31:328–340. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/31.2.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Obarzanek E, Kimm SYS, Barton BA, Van Horn L, Kwiterovich PO, Jr, Simons-Morton DG, Hunsberger SA, Lasser NL, Robson AM, Franklin FA, Jr, Lauer RM, Stevens VJ, Friedman LA, Dorgan JF, Greenlick MR. Long-term safety and efficacy of a cholesterol-lowering diet in children with elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol: Seven year results of the Dietary Intervention Study in Children (DISC) Pediatrics. 2001;107:256–264. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.2.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stone EJ, Osganian SK, McKinlay SM, Wu MC, Webber LS, Luepker RV, Perry CL, Parcel GS, Elder JP. Operational design and quality control in the CATCH multicenter trial. Prev Med. 1996;25:384–399. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McPherson RS, Hoelscher DM, Alexander M, Scanlon KS, Serdula MK. Dietary assessment methods among school-aged children: Validity and reliability. Prev Med. 2000;31:S11–S33. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baxter SD, Thompson WO, Litaker MS, Frye FHA, Guinn CH. Low accuracy and low consistency of fourth-graders' school breakfast and school lunch recalls. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102:386–395. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90089-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baxter SD, Thompson WO, Davis HC, Johnson MH. Impact of gender, ethnicity, meal component, and time interval between eating and reporting on accuracy of fourth-graders' self-reports of school lunch. J Am Diet Assoc. 1997;97:1293–1298. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(97)00309-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baxter SD, Thompson WO, Davis HC. Prompting methods affect the accuracy of children's school lunch recalls. J Am Diet Assoc. 2000;100:911–918. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(00)00264-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baxter SD, Thompson WO, Smith AF, Litaker MS, Yin Z, Frye FHA, Guinn CH, Baglio ML, Shaffer NM. Reverse versus forward order reporting and the accuracy of fourth-graders' recalls of school breakfast and school lunch. Prev Med. 2003;36:601–614. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(02)00030-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baxter SD, Thompson WO, Litaker MS, Guinn CH, Frye FHA, Baglio ML, Shaffer NM. Accuracy of fourth-graders' dietary recalls of school breakfast and school lunch validated with observations: In-person versus telephone interviews. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2003;35:124–134. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60196-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bransby ER, Daubney CG, King J. Comparison of results obtained by different methods of individual dietary survey. Br J Nutr. 1948;2:89–110. doi: 10.1079/bjn19480017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carter RL, Sharbaugh CO, Stapell CA. Reliability and validity of the 24-hour recall. J Am Diet Assoc. 1981;79:542–547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crawford PB, Obarzanek E, Morrison J, Sabry ZI. Comparative advantage of 3-day food records over 24-hour recall and 5-day food frequency validated by observation of 9- and 10-year-old girls. J Am Diet Assoc. 1994;94:626–630. doi: 10.1016/0002-8223(94)90158-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Domel SB, Thompson WO, Baranowski T, Smith AF. How children remember what they have eaten. J Am Diet Assoc. 1994;94:1267–1272. doi: 10.1016/0002-8223(94)92458-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Emmons L, Hayes M. Accuracy of 24-hr recalls of young children. J Am Diet Assoc. 1973;62:409–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greger JL, Etnyre GM. Validity of 24-hour dietary recalls by adolescent females. Am J Public Health. 1978;68:70–72. doi: 10.2105/ajph.68.1.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lytle LA, Murray DM, Perry CL, Eldridge AL. Validating fourth-grade students' self-report of dietary intake: Results from the 5-A-Day Power Plus program. J Am Diet Assoc. 1998;98:570–572. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(98)00127-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lytle LA, Nichaman MZ, Obarzanek E, Glovsky E, Montgomery D, Nicklas T, Zive M, Feldman H. Validation of 24-hour recalls assisted by food records in third-grade children. J Am Diet Assoc. 1993;93:1431–1436. doi: 10.1016/0002-8223(93)92247-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reynolds LA, Johnson SB, Silverstein J. Assessing daily diabetes management by 24-hour recall interview: The validity of children's reports. J Pediatr Psychol. 1990;15:493–509. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/15.4.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mack KA, Blair J, Presser S. Measuring and improving data quality in children's reports of dietary intake. In: Warnecke RB, editor. Health Survey Research Methods Conference Proceedings; DHHS Publication no. (PHS) 96-1013; Hyattsville, MD. 1996.pp. 51–55. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meredith A, Matthews A, Zickefoose M, Weagley E, Wayave M, Brown EG. How well do school children recall what they have eaten? J Am Diet Assoc. 1951;27:749–751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Samuelson G. An epidemiological study of child health and nutrition in a northern Swedish county. II. Methodological study of the recall technique. Nutr Metab. 1970;12:321–340. doi: 10.1159/000175306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stunkard AJ, Waxman M. Accuracy of self-reports of food intake. J Am Diet Assoc. 1981;79:547–551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Todd KS, Kretsch MJ. Accuracy of the self-reported dietary recall of new immigrant and refugee children. Nutr Res. 1986;6:1031–1043. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baranowski T, Islam N, Baranowski J, Cullen KW, Myres D, Marsh T, de Moor C. The Food Intake Recording Software System is valid among fourth-grade children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102:380–385. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90088-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Contento IR, Randell JS, Basch CE. Review and analysis of evaluation measures used in nutrition intervention research. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2002;34:2–25. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60220-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baranowski T, Henske J, Simons-Morton B, Palmer J, Tiernan K, Hooks PC, Dunn JK. Dietary change for cardiovascular disease prevention among Black-American families. Health Educ Res. 1990;5:433–443. doi: 10.1177/109019819001700205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bush PJ, Zuckerman AE, Taggart VS, Theiss PK, Peleg EO, Smith SA. Cardiovascular risk factor prevention in black school children: The “Know Your Body” evaluation project. Health Educ Q. 1989;16:215–227. doi: 10.1177/109019818901600206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gortmaker SL, Cheung LWY, Peterson KE, Chomitz G, Cradle JH, Dart H, Fox MK, Bullock RB, Sobol AM, Colditz G, Field AE, Laird N. Impact of a school-based interdisciplinary intervention on diet and physical activity among urban primary school children: Eat Well and Keep Moving. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:975–983. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.9.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindholm BW, Touliatos J, Wenberg MF. Predicting changes in nutrition knowledge and dietary quality in ten- to thirteen-year-olds following a nutrition education program. Adolescence. 1984;19:367–375. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luepker RV, Perry CL, Murray DM, Mullis R. Hypertension prevention through nutrition education in youth: A school-based program involving parents. Health Psychol. 1988;7(suppl):233–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McDonald WF, Brun JK, Esserman J. In-home interviews measure positive effects of a school nutrition program. J Nutr Educ. 1981;13:140–144. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nader PR, Stone EJ, Lytle LA, Perry CL, Osganian SK, Kelder S, Webber LS, Elder JP, Montgomery D, Feldman HA, Wu M, Johnson C, Parcel GS, Luepker RV. Three-year maintenance of improved diet and physical activity: The CATCH cohort. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:695–704. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.7.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nader PR, Sallis JF, Patterson TL, Abramson IS, Rupp JW, Senn KL, Atkins CJ, Roppe BE, Morris JA, Wallace JP, Vega WA. A family approach to cardiovascular risk reduction: Results from The San Diego Family Health Project. Health Educ Q. 1989;16:229–244. doi: 10.1177/109019818901600207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luepker RV, Perry CL, McKinlay SM, Nader PR, Parcel GS, Stone EJ, Webber LS, Elder JP, Feldman HA, Johnson CC, Kelder SH, Wu M. Outcomes of a field trial to improve children's dietary patterns and physical activity: The Child and Adolescent Trial for Cardiovascular Health (CATCH) JAMA. 1996;275:768–776. doi: 10.1001/jama.1996.03530340032026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perry CL, Bishop DB, Taylor G, Murray DM, Mays RW, Dudovitz BS, Smyth M, Story M. Changing fruit and vegetable consumption among children: The 5-A-Day Power Plus program in St. Paul, Minnesota. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:603–609. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.4.603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perry CL, Luepker RV, Murray DM, Kurth C, Mullis R, Crockett S, Jacobs DR., Jr Parent involvement with children's health promotion: The Minnesota Home Team. Am J Public Health. 1988;78:1156–1160. doi: 10.2105/ajph.78.9.1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perry CL, Luepker RV, Murray DM, Hearn MD, Halper A, Dudovitz B, Maile MC, Smyth M. Parent involvement with children's health promotion: A one-year follow-up of the Minnesota Home Team. Health Educ Q. 1989;16:171–180. doi: 10.1177/109019818901600203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perry CL, Lytle LA, Feldman H, Nicklas T, Stone E, Zive M, Garceau A, Kelder SH. Effects of the Child and Adolescent Trial for Cardiovascular Health (CATCH) on fruit and vegetable intake. J Nutr Educ. 1998;30:354–360. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reynolds KD, Franklin FA, Binkley D, Raczynski JM, Harrington KF, Kirk KA, Person S. Increasing the fruit and vegetable consumption of fourth-graders: Results from the High 5 Project. Prev Med. 2000;30:309–319. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schinke SP, Singer B, Cole K, Contento IR. Reducing cancer risk among Native American adolescents. Prev Med. 1996;25:146–155. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.0040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Walter HJ. Primary prevention of chronic disease among children: The school-based “Know Your Body” intervention trials. Health Educ Q. 1989;16:201–214. doi: 10.1177/109019818901600205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fowler FJ., Jr . Reducing interviewer-related error through interviewer training, supervision, and other means. In: Biemer PP, Groves RM, Lyberg LE, Mathiowetz NA, Sudman S, editors. Measurement Errors in Surveys. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1991. pp. 259–278. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Billiet J, Loosveldt G. Improvement of the quality of responses to factual survey questions by interviewer training. Public Opin Q. 1988;52:190–211. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fowler FJ, Jr, Mangione TW. Applied Social Research Methods Series. Vol. 18. Sage Publications; Newbury Park, CA: 1990. Standardized Survey Interviewing: Minimizing Interviewer-Related Error. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dennis B, Stamler J, Buzzard M, Conway R, Elliott P, Moag-Stahlberg A, Okayama A, Okuda N, Robertson C, Robinson F, Schakel S, Stevens M, Van Heel N, Zhao L, Zhou B. INTERMAP: The dietary data—process and quality control. J Hum Hypertens. 2003;17:609–622. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Simons-Morton BG, Parcel GS, Baranowski T, Forthofer R, O'Hara NM. Promoting physical activity and a healthful diet among children: Results of a school-based intervention study. Am J Public Health. 1991;81:986–991. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.8.986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]