Reason for posting: Diane-35, an oral contraceptive with anti-androgen properties, has been heavily marketed to young women1 and has seen its Canadian sales jump by 45% between 2000 and 2001 alone.2 However, many physicians may be unaware of concerns about the drug's safety profile3 and the fact that it is not approved for use solely as an oral contraceptive.4 The UK Committee on the Safety of Medicines recently issued a warning on the drug's risk of venous thromboembolism,5 which was repeated verbatim by Health Canada in late December 2002.

The drug: Diane-35, which contains ethinylestradiol (35 μg) and cyproterone acetate (2 mg), provides effective birth control but is not indicated as such.4 Cyproterone acetate has anti-androgen effects resulting in part from its blockade of androgen receptors, and Diane-35 is approved only as therapy for androgen-sensitive skin conditions, including hirsutism and severe acne unresponsive to oral antibiotic therapy.4 Treatment with Diane-35 should be discontinued 3–4 menstrual cycles after a woman's skin condition has resolved.4,5 Warnings to minimize a woman's exposure to the drug result in part from the association with venous thromboembolic disease.

Since cases of venous thromboembolism were first reported in the 1960s in women taking combination oral contraceptives, preparations have been developed with lower doses of estrogen (typically 30–40 μg of ethinylestradiol, as compared with > 50 μg originally) and different progestagen components.6 The low-estrogen preparations are associated with lower rates of venous thrombosis, but they still carry risks of venous thromboembolism apparently related to their progestagen component. So-called “third-generation progestagens” (e.g., desogestrel) are associated with about double the risk of venous thrombosis of either the first- (norethindrone) or second-generation (levonorgestrel) progestagens,7,8,9 although the association is controversial.10 A Danish study showed no difference in risk of venous thromboembolism between levonorgestrel and cyproterone users;11 however, a large case–control study involving nearly 100 000 women in the United Kingdom showed that women taking oral contraceptives containing cyproterone had quadruple the risk of venous thromboembolism as those taking levonorgestrel combinations.3 Regarding fatal pulmonary embolism, a case–control study in New Zealand found that, compared with women taking no oral contraceptives, the adjusted odds ratio was 17.6 (95% confidence interval [CI] 2.7–113) among women taking cyproterone acetate, 5.1 (95% CI 1.2–21.4) among levonorgestrel users and 14.9 (95% CI 3.5–64.3) among desogestrel or gestodene users.12

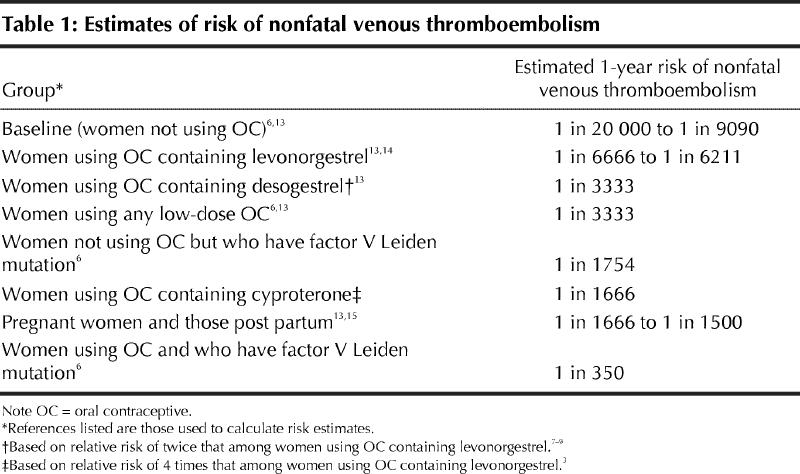

Oral contraceptives users at increased risk of venous thromboembolism include those who are obese7 and those who harbour prothrombotic mutations (factor V Leiden carriers have 35 times the risk as women without this mutation).6 The degree to which other risk factors for venous thrombosis (injury, immobility, postoperative status or postpartum status) affect the risk associated with oral contraceptives is unknown. Table 1 lists various estimates of the risks of nonfatal venous thromboembolism. Unlike arterial thrombosis,16 the risk of venous thrombosis among contraceptive users appears unaffected by the woman's age, history of hypertension or smoking status.7 Venous thrombosis develops in women taking combination oral contraceptives usually within the first year after starting the drug.17

Table 1

What to do: Diane-35 should be reserved for temporary use in women with serious acne and should not be used solely as an oral contraceptive. All women who use combination oral contraceptives are at risk of venous thromboembolism and should be informed of this rare but potentially serious adverse effect, particularly if they are taking Diane-35. Clearly caution, and not panic, is warranted. For example, switching 2220 women from Diane-35 to an oral levonorgestrel contraceptive for 1 year would prevent 1 case of nonfatal venous thromboembolism. Physicians should consider not prescribing Diane-35 for women at risk of venous thromboembolism (especially those who carry prothrombotic mutations), while recognizing that such an approach to preventing venous thrombosis is limited by the fact that most venous thrombotic events are truly idiopathic (i.e. the women have no clinically recognizable risk factors).6

Eric Wooltorton CMAJ

References

- 1.Marketing Diane-35. Disclosure [television program]. Toronto: Canadian Broadcasting Corporation; 2003 Jan 14. Transcript available: www .cbc .ca /disclosure/archives/030114_diane/marketing .html (accessed 2003 Jan 21).

- 2.Top 200 prescribed medications — year 2001 [table]. Toronto: IMS Health Canada. Available: www .imshealthcanada.com/htmen/3_2_14.htm (accessed 2003 Jan 21).

- 3.Vasilakis-Scaramozza C, Jick H. Risk of venous thromboembolism with cytoperone or levonorgestrel contraceptives. Lancet 2001;358: 1427-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Diane-35 [product monograph]. In: Compendium of Pharmaceuticals and Specialties. Ottawa: Canadian Pharmacists Association; 2002. p. 493-5.

- 5.Cyproterone acetate (Dianette): risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE). Curr Probl Pharmacovigilance 2002;28:9-10. Available: www.mca.gov.uk/ourwork/monitorsafequalmed/currentproblems/cpprevious.htm#2002 (accessed 2003 Jan 21).

- 6.Vandenbroucke JP, Rosing J, Bloemenkamp KWM, Middeldorp S, Helmerhorst FM, Bouma BN, et al. Oral contraceptives and the risk of venous thrombosis. N Engl J Med 2001; 344: 1527-35. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Venous thromboembolic disease and combined oral contraceptives: results of international multicentre case–control study. World Health Organization Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception. Lancet 1995;346:1575-82. [PubMed]

- 8.Kemmeren JM, Algra A, Grobbee DE. Third generation oral contraceptives and risk of venous thrombosis: meta-analysis. BMJ 2001;323:131-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Jick H, Kaye JA, Vasilakis-Scaramozza C, Jick SS. Risk of venous thromboembolism among users of third generation oral contraceptives compared with users of oral contraceptives with levonorgestrel before and after 1995: cohort and case–control analysis. BMJ 2000;321:1190-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Skegg DCG. Third generation oral contraceptives. Caution is still justified [editorial]. BMJ 2000;321:190-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Lidegaard Ø, Edström B, Kreiner S. Oral contraceptives and venous thromboembolism: a five-year national case–control study. Contraception 2002;65(3):187-96. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Parkin L, Skegg DC, Wilson M, Herbison GP, Paul C. Oral contraceptives and fatal pulmonary embolism [letter]. Lancet 2000;355:2133-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Mills AM, Wilkinson CL, Bromham DR, Elias J, Fotherby K, Guillebaud J, et al. Guidelines for prescribing combined oral contraceptives. BMJ 1996;312:121-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Jick H, Jick SS, Gurewich V, Myers MW, Vasilakis C. Risk of idiopathic cardiovascular death and nonfatal venous thromboembolism in women using oral contraceptives with differing progestagen components. Lancet 1995;346:1589-93. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Bloomenthal D, von Dadelszen P, Liston R, Magee L, Tsang P. The effect of factor V Leiden carriage on maternal and fetal health. CMAJ 2002; 167(1):48-54. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Hoey J. Oral contraceptives and myocardial infarction. CMAJ 2002;166(7):931. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Farley TM, Meirik O, Marmot MG, Chang CL, Poulter NR. Oral contraceptives and risk of venous thromboembolism: impact of duration of use. Contraception 1998;57(1):61-5. [DOI] [PubMed]