Abstract

Background

For hundred of years, people in the region encompassed by the Afghanistan-Iran-Pakistan borders (AIP region) have been challenged by conflict and political and civil instability, mass displacement, human rights abuses, drought, and famine. It not surprising that health and quality of life of vulnerable groups in this region are among the worst in the world. In general, women and children, in particular girls, in the AIP region have had especially limited access to healthcare. Women and children have dramatically high rates of communicable and non-communicable disease, morbidity, and mortality and a general low life expectancy that is rapidly declining. In spite of national and international efforts to improve health status of vulnerable populations in this region, the key underlying sociocultural determinants of health and disparities (ie, gender, language, ethnicity, residential status, and socioeconomic status) have not been systematically studied, nor have their relationships to environmental challenges been examined.

Objectives

We set out to summarize existing information regarding the sociocultural, environmental, and traditional determinants of health disparities among different population groups in the AIP region; identify gaps in research regarding the communities' needs in the region; and highlight factors that must be considered in the design and implementation of future health intervention studies in the region.

Methods

We reviewed current health literature, official documents, and other information (eg, reports of UN agencies) related to the social, cultural, and environmental factors that may influence the health outcomes of subpopulations living in the AIP region. We also interviewed individuals who had recently worked in this region.

Results

Overall, the health problems faced by this underdeveloped region can be categorized into those resulting from lack of essential supplies and services and those stemming from the existing cultural practices in the area. The low health status of the people, particularly women and children, in the AIP region is associated with not only poor hygiene and lack of water but also limited knowledge and lack of access to healthcare services. In addition, cultural, political, and socioenvironmental factors play a role, including gender inequality and differences between languages spoken locally in the region and those most often used in written health education materials.

Conclusion

Future intervention programs designed for this region must use culturally sensitive strategies not only to provide health information and health services but also to address the underlying nonmedical determinants of health related to gender inequalities

Introduction

Current thinking in public health has moved beyond the physical, biological, behavioral, and environmental causes of disease to embrace the relationships between health and social context, ie, poverty, gender, culture, and ethnicity.[1-6] Examination of social, political, economic, cultural, and environmental factors is important for understanding community health status and for demonstrating underlying health disparities among different subpopulations.[7-9] However, to date, much of the knowledge we have about health determinants and disparities derives from research and analysis of the interactions between socioeconomic factors and health in developed countries, which may not necessarily be relevant to situations in less-developed nations.[7,10,11] Moreover, interventions developed on the basis of such knowledge have not been extensively studied in developing countries and, particularly, in highly vulnerable communities within these countries.[12-14] In addition, information that is available, both from within and outside the health sector of less developed countries, is often not effectively used for development of appropriate community health interventions.[2,4,5,7,8,15] These gaps in knowledge are themselves a reflection of the broader "10-90 gap," wherein 90% of the world's health research dollars are devoted to 10% of the burden of disease in more-developed countries.[15-17]

With increasing globalization, however, has come the increased recognition of the importance of addressing health disparities globally,[17] as evident in the 2002 World Health Organization report of the Commission on Macroeconomics and Health.[16] Following a widespread decline in institutional commitments and funding for development and research into correcting global health disparities in the 1990s, positive developments have been emerging. A particularly encouraging step in this regard has been the Global Health Research Initiative in Canada, whereby the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the International Development Research Centre (IDRC), the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA), and Health Canada have agreed to a strengthened and coordinated funding of health research into correcting global health disparities.[17] In preparation for a proposal to the Canadian global health funding agencies to implement and evaluate an evidence-based intervention to provide health information and health services for women and children living in the region encompassed by the Afghanistan-Iran-Pakistan borders (AIP region), we reviewed current health literature, official documents, and other information (eg, UN agencies reports) related to the social, cultural and environmental factors that may influence the health outcomes of subpopulations living in the AIP region. We also interviewed individuals who had recently worked in this region.

The objectives of this article are to summarize existing information regarding sociocultural, environmental, and traditional determinants of health disparities among different population groups in the AIP region; identify gaps in research regarding the communities' needs in the region; and highlight factors that must be considered in the design and implementation of future health intervention studies in the region.

Methods

This study included a review of relevant literature (eg, Medline, Social Sciences Citation Index), PubMed, Educational Resources Information Center [ERIC] database ), governmental and health officials' documents and reports from 3 countries (Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan), and of the UN agencies' (ie, UNICEF, WHO, UNESCO, FAO, UNFPA, UN Commission on Human Rights) and the World Bank's weekly, monthly, and annual reports and documents. Particular effort was made to collect information related to sociocultural, environmental, and health issues of people -- particularly women and children -- who live along the borders of the AIP region. In addition, we reviewed the most recent health statistics and information reported by health officials in each of the 3 countries. These documents and data were obtained directly from the Ministries of Health of Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan or through searching their Web sites. Several Canadian researchers and health workers who have recently returned from working in this area were also interviewed. Our local academic colleagues, researchers, and community partners working in Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan were asked to provide up-to-date information in terms of women and children's health status by fax, mail, or emails.

Results

People who live along the borders between Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan have the highest burden of most preventable diseases in South Asia.[18-20] This is commonly assumed to be associated with many different factors – ranging from an unusually large number of uprooted people in the region (ie, refugees from Afghanistan, migrants from Pakistan, and Iranian farmers fleeing villages ravaged by unprecedented drought), to the behavioral patterns and traditional practices in the region, to the rapidly deteriorating environmental conditions that lead to internal immigration from rural areas to urban centers.[21-26] Federal, provincial, and local governments have devoted substantial efforts to improve the health and well-being of people in the region,[18,20,23] and there has been considerable activity in the region by local non-government organizations (NGOs) and international NGOs and agencies.[24,25,27,28] Despite these efforts, which have mainly been in the form of disaster response and symptom relief,[28] marginal progress has been reported in the past 3 decades in terms of reduced disparities in health.[25,26,29] This may in part be related to the fact that few, if any, interdisciplinary, community-participatory studies have set out to identify non-medical determinants of women and children's health status in the AIP region.[26, 30,31] Some of the specific findings of this study are summarized in the following sections.

Geographic and Linguistic Profile

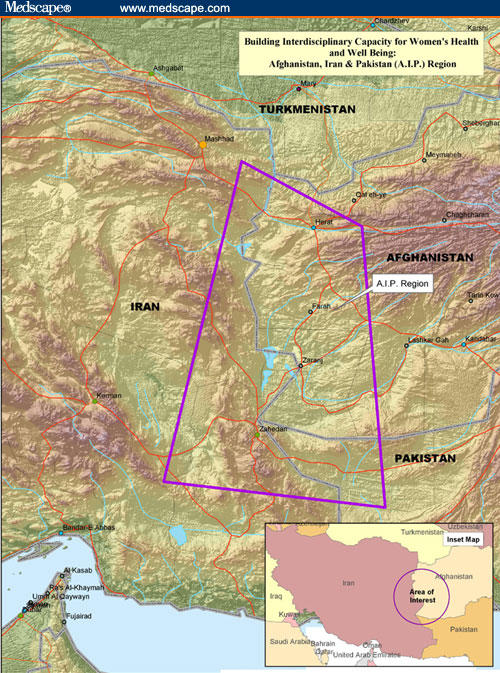

As shown in Figure 1, the 3 countries of the AIP region share a long border (approximately 1500 kilometers) along which people share similar cultures, language, and customs.[25,28] This region is home to approximately 4 million people, of whom 1.5 million are Afghani, 2 million are Iranian, and 500,000 are Pakistani.[21,28] The border provinces include Harat, Farah, and NimRooz in Afghanistan; Sistan-and-Baluchestan and southeast Khorasan in Iran; and Baluchistan in Pakistan.[28] The region has 2 main local languages (Baluchi and Dari), which are shared across the national borders.[32,33] Baluchi is a modern Iranian language of the Indo-Iranian group of the Indo-European language family.[32] Baluchi speakers live mainly in an area now composed of parts of southeastern Iran and southwestern Pakistan -- once the historic region of Baluchistan. They also live in Central Asia and southwestern Afghanistan. It is estimated that more than 6 million people communicate in Baluchi today.[28] The other common language is Dari,[33] the Afghan dialect of Farsi (Persian) and of the Iranian branch of the Indo-Iranian family of languages. It is written in a modified Arabic alphabet, and it has many Arabic and Persian loanwords. More than 2 million people within the borders of Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan speak Dari today.[28]

Figure 1.

The AIP region-South Asia.

Population Health Status in the Region

Overall, the low health status of people in the AIP region, particularly women and children, is associated with poor hygiene, low literacy, and lack of access to healthcare services, cultural practices, stereotyping and discriminatory attitudes, and environmental problems.[28,34-37] In spite of local and international efforts to improve the status of women and children in this area, and a general concern for their education, health, and quality of life, marginal improvement has been reported in the past decades in terms of reduced gender inequalities and health and social disparities.[37-40] The problem of identifying effective strategies is compounded by the fact that there appear to be wide gaps between the data on health needs derived from statistics provided by health officials in the region and the observed health needs of the subpopulations. For instance, although the disparities between men and women in terms of life expectancy; access to education, health and social services; and overall quality of life have become wider in the past few years in the AIP region,[22,29,31,34,41] these inequalities are not reflected in the official documents in any of the 3 countries. The issues of AIDS, other sexually transmitted diseases, suicide attempts, and women trafficking in the region, reported by international NGOs as problems that need immediate attention,[24-28] have not been considered as priorities by local decision makers. By contrast, the limited food provision and other short-term assistance by local and central governments have not resolved the fundamental problems in the region.

In general, almost all reviewed reports and documents demonstrated that women and children are the most vulnerable populations at the AIP borders.[18,23-25,30,31,42,43] Maternal and infant mortality rates are high, especially among Afghani refugees ((Table 1)).[34,36,41,44] Many studies have linked these problems to lack of maternal healthcare and childcare, as well as inadequate first-level referral centers in the region.[36,37,44] Of the 3 countries, Iran has the lowest infant mortality rate (IMR) and under-5 mortality rates (U5MR), peaking at 35 and 46 per 1000 live births, respectively.[31,45] In Pakistan, a country where the status of children is terribly low -- especially for female children -- the IMR is 84 per 1000 live births, and the U5MR is 109 per 1000.[18] The situation in Afghanistan is even more alarming, with an IMR of 165 and a U5MR that soars to 257.[25,30,44,46] The statistics for these individual countries, however, do not compare to the dire state of the AIP region, where a quarter of children die within their first year, and half die before the age of 5, mainly due to respiratory tract infections and severe diarrhea caused by chronic malnutrition.[28,47] The international agencies UNICEF, UNFPA, and UNESCO have conducted different needs assessments in the AIP region and report excess mortality and morbidity rates among children who live with their parents at the border areas, particularly female children.[19,24,25,48-50]

Table 1.

Selected Health Data in the AIP Region and Surrounded Countries

| #x000A0; | AIP | Afghanistan | Iran | Pakistan |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal mortality ratio per 100,000 live births | 520-560 | 1900 | 76 | 500 |

| Infant mortality per 1000 live births | 250 | 165 | 35 | 84 |

| Under-5 mortality per 1000 live births | 500 | 257 | 46 | 109 |

Source: UN agencies' reports, 2000.

Environmental Issues in the Region

Water supply is a major challenge in the region as a result of 5 consecutive years of drought, dry lands, and lack of natural water resources.[21,47,51] The only natural waterway in the border region of Iran and Afghanistan is the Hillman River. Its flow to the border area was blocked from the Afghanistan shore during the Taliban era.[21,51] This blockage has caused tremendous environmental and climate changes in the region, specifically in the provinces of Sistan-and-Baluchestan in Iran and NimRooz and Farah in Afghanistan.[21,28,51] There is no other natural waterway between Iran and Pakistan or between Afghanistan and Pakistan borders. Due to lack of adequate water resources, and also traditional unhygienic practices among different population groups in the region (eg, using open fields for sanitation and cooking,[52]) the sanitation improvement programs developed by local health officials and international NGOs have had limited success.[47] The lack of water particularly affects women, as they are mainly responsible for collecting and providing clean water for the family.[35,40,53] Sometimes they have to travel for kilometers and/or stand in day-long lines to obtain clean, drinkable water.[51,54]

Food Security, Literacy, Sociocultural and Gender Issues in the Region

Food Security

The UN Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) has established a food and nutrition monitoring system in South Asia and has identified Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan as having moderate to severe undernourishment, stunting, and wasting among children younger than 5 years of age, specifically among girls.[43] In a recent report, the UN stated that ".... in times of diminished food resources, girls and their mothers are often last to be fed, resulting in a diet low in calories and protein."[50] Food insecurity and health threats are likely to increase even further in designated camps for refugees.[28,34] Old women and young girls, as well as families whose males have died or been injured in war or conflicts, have further problems in most refugee camps in the region because of discriminatory attitudes and ignorance.[28,47]

Literacy

Hundreds of thousands of children in the AIP region are failing to receive education.[23,25,26,28,29,47,49] Governmental and nongovernmental documents indicate that most children were not in school because there were none or they were too far away.[25,47] In addition to the lack of access to a school, there is a persistent lack of teachers in the schools that do exist.[26,29,31,48] Moreover, many families believe that it is more beneficial for their children to work than to go to school.[23,34,49,50] Thus, literacy in the region is poor, and female literacy in particular needs extraordinary efforts to improve.[48,55] Oxfam's study in 2001 indicated that more than 85% of the Afghani women have never been to school;[49] in other reports, only 5% to 10% of studied Afghan women and girls could read or write.[26,42]

Religion

The dominant religion practiced in the area is Islam, which is associated with gender-specific beliefs and customs relating to health practices and marriage.[25,35,39,40,54,56-59]

Gender Roles

In most cases, men have the dominant role in governing the communities, both politically and socially.[39,40] Women have the dominant role in feeding the family (purchasing, handling, and preparing foods), water collection, and taking care of elders' and children's health.[28,47] They participate in health-related meetings and classes, eg, family planning and health education.[28,34]

Gender Inequality

Discriminatory cultural-behavioral practices at home and in the community have caused severe developmental health and social disparities between children and adults, between men and women, and between boys and girls in the AIP region.[28,40,41,46,47,58] Priority for healthcare in most cases is given to boys -- eg, they receive higher-nutrient foods, better places to sleep, better clothing, and more emotional support.[40,50] In addition, boys are more likely to attend schools, whereas girls have limited access to education, specifically at the level of high school and postsecondary education.[25,49] Conservative opposition at home and in community to the education of women is a major reason for keeping girls out of school.[55] Even among educated women, there is discrimination with respect to employment and wages, and acts of harassment occur even in more-developed urban areas.[28,39,40,54] Overall, the priority for hiring and promotion is mainly given to men, even in the face of equal educational and experience qualifications.[40,54]

Young girls have little authority to select their own husbands: The senior male family member (father, brother, or grandfather) selects a spouse on the basis of political, economic, and tribal affiliations.[39,54,58] Family and tribal intermarriage is very common, which may contribute to genetic and family-related health problems.[25,28] Only men have the right to divorce, and they are allowed more than 1 wife.[38,40] This has been cited as reason for a high rate of attempted suicide by young women who have no other means to end an unwanted marriage.[38]

Despite their extraordinary contributions to the health and well-being of the family, women living at the AIP borders face a variety of health-related problems that are not attended to or acknowledged by other family members.[38] Their multiple responsibilities at home, their social isolation and lack of support at home and in the community, and their lack of decision-making power, lack of access to education, and lack of access to adequate health services are among the highly prevalent sociocultural factors that can lead to physical decline and increased emotional and mental strain.[38]

Discussion

As a result of the chaos of decades of warfare mass displacement, human rights abuses, drought, and famine, and the consequent neglect of public health functions, Afghanistan has become a reservoir for infectious diseases such as malaria, polio, cholera, and tuberculosis.[23,25,28,47] These diseases are not only debilitating the resident population, they are also exported to neighboring countries and can trigger epidemics, especially when introduced into areas with limited medical resources. Iran and Pakistan shelter an estimated 2 million Afghan refugees in their border provinces.[28,34,49] Some refugees have settled permanently in this region and are living in conditions comparable to those of the local residents.[28] In general, the more recent arrivals live in more stressful conditions until they get established.[28,34]

Although healthcare is universal and provided without charge in Iran and Pakistan, the medical infrastructure in the areas with the largest numbers of refugees is less dense than in other parts of these 2 countries, which means that fewer resources can be devoted to screening and treating newcomers.[28] In addition, because many of the refugees are unaware of available services and even of the microbial nature of infectious disease (which has been attributed to low literacy levels),[34] healthcare seeking and usage are disproportionately low in this population. A simple review of the medical records of refugees kept by regional health clinics reveals that preventable diseases are responsible for the burden of excess morbidity and mortality.

The health problems faced by this underdeveloped region can be categorized into those resulting from lack of essential supplies and social services and those stemming from the existing behavioral and traditional practices in the area. Essential supplies that are inadequately delivered to the AIP region include proper nutrition, clean water, contraceptives, immunization, essential medications, and simple therapeutic devices, such as those for oral rehydration and minerals. Furthermore, many children in the region are suffering from night blindness, a symptom of malnutrition common among poor populations, yet preventable by vitamin A supplements. Essential services that are lacking include maternal and mental healthcare, civil rights protection, social work services, proper transportation in emergencies, and schooling facilities generally and especially for girls and women. These supplies and services need to be provided by the provincial and federal governments of the 3 involved countries, as well as by the local and international NGOs.

UNICEF and UNFPA have developed different projects to alleviate the burden of night blindness among children and to improve women's health status in the region. FAO has also conducted many studies to improve the nutritional status of children in the region. In addition, World Bank has developed projects in the past 2 decades to improve the water supplies and sanitation practices in this area. However, few studies have assessed the non-medical determinants of health issues, and none have examined the impact of these underlying factors on population health outcomes in the AIP region.

Why Have Health Education Efforts in the Region Failed?

Health education in the AIP region has not been successful despite a long history of effort.[38,42,48] In addition, more recent national and international efforts have met with little progress. Why is this? To begin with, most international NGOs deal with disaster relief and humanitarian aid activities,[28,43,49] rather than address ongoing and long-term needs of communities. Second, international NGOs generally work under the control of central governments in the involved countries.[24,25,38] In the AIP region, the central governments historically have ignored local communicating languages for many years for political, social, and economic reasons,[28,39-41] and their rules and mandates have influenced the international NGOs' activities. So, for example, the development and production of health education materials often are funded by an international NGO but produced by local health departments,[10,60] and they are required to fulfill the central governments' mandates and rules about producing health materials in official languages.[29,48] By law, the language of the school system is the official language communicated in each of the 3 countries, and health education materials produced for use in the school system must also be conveyed in official languages.[47] In addition, Iran plays a dominant role in providing health services in the region,[25,28] and they mainly produce health education materials in Farsi.

Thus, one of the most significant problems identified by many researchers is that health education materials and schoolbooks provided by international agencies and NGOs are written in the official languages -- Farsi, Pashto, and Punjabi-- of each of the 3 countries,[23,26,28,34,38,61] whereas most people in the AIP region, particularly women, communicate in either Baluchi or Dari.[38] In general, the provision of basic education is still a major challenge for AIP region,[29,38] and no attempts have been made to provide adult education for older family members in the community.[26,28,47] Women's limited knowledge of the official languages and low literacy levels have been a barrier to effective receipt of information about health issues. This has had an immediate impact on their own and their families' health and quality of life, particularly their children's, as it is the women who mostly visit health clinics and health houses alongside their children to receive primary care services or attend health education classes.[48,49] In addition, because most local women's literacy levels are low, they have limited capacity to receive proper training by international staff.[28,49] Therefore, non-local volunteers or paid staff of an NGO take charge of educating local communities, and in most cases they have to use health education materials developed in official languages. Further, it should be noted that community-participatory programs are not supported or practiced by local and central governments.[38,47]

Another one of the most important factors that fosters continued problems with language is the short stays of international NGOs in the region.[47,49] The short stays prevent staff from learning the local languages to a degree that enables effective communication with the people of the region and to train and involve local women in their programs.[47] Notably, however, some of the staff of an international aid agency stationed at the border between Afghanistan and Iran who were interviewed recently by the authors remarked that Dari was quite easy to learn. They said that speaking a few sentences or greetings in Dari to the local people helped them to win many hearts, both at work and in the street. The aid workers also noted that the most challenging part of their stays in the region was their inability to communicate properly with people, especially with women, who traditionally are not allowed contact with foreigners, men in particular.[53]

The lack of progress in health education in the region may be also related to the international NGOs' failure to contribute effectively to the region's overall development. Although most foreign agencies and international NGOs state that their role is to help marginalized people,[47] local people and community leaders often believe that these agencies are too focused on completing their assigned projects[28] and do not learn sufficiently about the culture or people of the region to make the programs more relevant to the community and sustainable for the long term. Corruption and nepotism within some aid agencies in the region[28,47] have also added to a feeling of distrust by the local community. In addition, the magnitude of inequality in the region,[39,40] and the apparent inability of international agencies to reduce it,[47] is another reason for such attitudes toward foreigners by the local community.

Improving the Health of Women and Children in the AIP Region

Many of the customs and traditional practices rooted in the culture and religion have considerably influenced the health and quality of life of women and children and caused the considerable disparities related to health and social status between men and women and boys and girls in the region. Because of the similar cultural and religious practices among people in the AIP region, some studies indicate that in the long run, one of the best ways to reach and assist vulnerable populations, especially women and children, is through social, economic, and political empowerment of women in the border areas.[47] There is a largely under-realized potential capability among women in the region to take charge of community activities, including environmental and health-related issues.[35,54] In addition, female healthcare providers working in NGOs, such as Red Crescent Society (ARCS), and rural "health houses" have been identified by many investigators as a useful way to communicate and provide basic and health literacy in the region of interest.[49] However, it seems the language-related problems will persist, unless the regional languages (ie, Baluchi or Dari) are used to develop basic education and health information materials.

Communities in the AIP region need programs to provide emergency relief, education for all, easy access to primary healthcare and social services, and empowering capacity. Although these programs are urgent, there is still a need to refocus local and international efforts to promote gender equality and long-term sustainable development and environmental improvements.

Conclusion

Government officials, international agencies, and NGOs in the 3 countries involved are investing considerable efforts to improve the health and well-being of people in the marginalized communities in the AIP border area. Little progress, however, has been observed so far regarding improvements in gender equality and reducing health and social disparities in particularly vulnerable subpopulations living in this disadvantaged region. To better design effective and sustainable intervention programs, the impact of underlying sociocultural and environmental determinants (gender, language, ethnicity, residential status, and socioeconomic status) in relation to social and health disparities of women and children in the AIP region must be studied.

Some conclusions and recommendations that ought to be considered in the design of future health interventions in this region emerge from our review. Broadly speaking, the objectives of programs aiming to improve the health and social status of vulnerable groups in this region should fall into the following 4 categories:

Healthcare: Establish and operate affordable primary and emergency healthcare services, accessible by vulnerable people, primarily women and children. This will minimize the burden of morbidity and mortality from both communicable and non-communicable diseases among marginalized populations.

Education and empowerment: Support school and other literacy programs for all, particularly for women and young girls, to reduce illiteracy in the region. This would empower young women to build sustainable livelihoods and could narrow the gender inequality in the region.

Awareness: Conduct local campaigns and forums to build community capacity and to increase public awareness of community health, human rights, and relevant issues. More familiar and appropriate language(s) and culturally sensitive and accepted methods must be applied.

Sustainable development: Plan and conduct longer-term programs to build and strengthen the community infrastructure in the region. Addressing the impact of the environmental, social, economic, and cultural determinants of health would facilitate community development in the region. Particular attention should be paid to the factors affecting women and children's health and the traditional practices that may promote gender inequality in terms of health, education, wealth, and decision making.

In conclusion, the people within the AIP borders need healthcare services and culturally appropriate awareness campaigns to improve women's and children's health, as well as programs to help children, especially young girls, find new opportunities for education. More research is needed to determine and measure the impact of underlying cultural factors that can be modified to promote the empowerment of women and facilitate sustainable changes needed to support health.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Mr. Darrin Grund, project manager, and Mr. Luan Vo, research assistant, at the Institute for Health Research and Education at Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, British Columbia, for their assistance with designing and revising the map.

Footnotes

This article is supported by funding from the Institute of Health Promotion Research, University of British Columbia.

Correspondence: Iraj M. Poureslami, Adjunct Professor, Institute of Health Promotion Research, the University of British Columbia (UBC), Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z3, Canada. E-mail: pouresla@interchange.ubc.ca

Contributor Information

Iraj M Poureslami, Iran University of Medical Sciences and Institute of Health Promotion Research, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

David R MacLean, Institute for Health Research and Education, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada.

Jerry Spiegel, Liu Institute for Global Issues, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

Annalee Yassi, Institute of Health Promotion Research, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

References

- 1. Green LW, Richard L, Potvin L. Ecological foundations of health promotion. Am J Health Promot. 1996;10:270-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Richard L, Potvin L, Kishchuk N, Prlic H, Green LW. Assessment of the integration of the ecological approach in health promotion programs. Am J Health Promot. 1996;10:318-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stokols D. Translating social ecological theory into guidelines for community health promotion. Am J Health Promot. 1996;10:282-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Raphael D, Steinmetz B, Renwick R, et al. The Community Quality of Life Project: a health promotion approach to understanding communities. Health Promotion International. 1999;14:197-210. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yassi A, Mas P, Bonnet M, et al. Applying an ecosystem approach to the determinants of health in Centro Habana. Ecosystem Health. 1999;5:3-19. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stokols D. Establishing and maintaining healthy environments: toward a social ecology of health promotion. American Psychologist. 1992;47:6-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Marmot M, Wilkinson R. Social determinants of health. Health Promotion International. 2000;15:87-89. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lasker RD, Weiss ES. Broadening participation in community problem solving: a multidisciplinary model to support collaborative practice and research. J Urban Health. 2003;80:14-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pilon AF. Experience and Learning in the Ecosystemic Model of Culture. Sao Paulo, Brazil: University of S. Paulo Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hubley J. Barriers to health education in developing countries. Health Educ Res. 1986;1:233-245. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sakurai N, Tomoyama G, Watanabe T, Fujiwara Y, Hoshi T. Public participation and empowerment in health promotion. Nippon Eiseigaku Zasshi. 2002;57:490-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Laverack G, Esisakyi B, Hubley J. Participatory learning materials for health promotion in Ghana - a case study. Health Promotion International. 1997;12:21-26. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chalmers B. International Research: Promoting a Multidisciplinary Approach to Perinatal Health Care. Women's Health matters: Health Bytes. Sunnybrook and Women's College Health Sciences Centre; March 2002.

- 14. Mittelmark M. Promoting social responsibility for health: health impact assessment and healthy public policy at the community level. Heath Promotion International. 2001;16:269-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Global Forum for Health Research. The 10/90 Report on Health Research 2001-2002. http://www.globalforumhealth.org/pages/index.asp. Last accessed July 22, 2004.

- 16. World Health Organization. Report of the Commission on Macroeconomics and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2002.

- 17. Spiegel JM, Labonte R, Hatcher-Roberts J, Girard J, Neufeld V. Tackling the 10-90 gap: a report from Canada. Lancet. 2003; 362:917-918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fikree F, Midhet F, Sadruddin S, Berendes HW. Maternal mortality in different Pakistani sites: ratios, clinical causes and determinants. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1997;76:637-645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. UNICEF. Special Measures for Infants and Children. June 2003 report.

- 20. Brundtland GH. Afghanistan: rebuilding a health system. JAMA. 2002;287:2354-2355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Carliez S. The Drought Story: Iranian Red Crescent Works to Maintain Water Delivery to Afghan Refugees. Shirabad, Iran. November 2001.

- 22.Massarrat MS, Tahaghoghi SM. Iranian National Health Survey: A Brief Report. Archives of Iranian Medicine. 2003;18:1-9. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ministry of Health - Iran. Sistan and Baluchestan Province and the Borderlines health and well-being features. Sistan and Baluchestan, Iran: Iran Ministry of Health Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 24. UNICEF. Nutrition status of children in Iran. UNICEF-Iran Publishing Inc. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 25. UNFPA and UNICEF. Health and well-being of different population groups in Iran and its borders. WHO - Iran. 2000.

- 26. International Rescue Committee. Building a future for Afghan children: IRC education program in Pakistan. IRC publishing Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mayor S. UNICEF Report Calls for Children to Move to the Top of the Health agenda. BMJ. 2000;321:1490-1492. [Google Scholar]

- 28. United Nations. Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan (AIP): Closed door policy; Afghanistan refugees in Pakistan and Iran. Human Rights Watch. 2003,14;1-45. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mohsenpour B, Kiamanesh A. Evaluation of the education of rural girls project in Iran (Sistan and Baluchestan province data). United Nations Children's Fund and Literacy Movement Organization; 2000.

- 30. Forouzain M, Malekafzali H, Bahrami B. Growth of a group of low-income infants in first year of life in Southeast Iran and the border areas. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics and Environmental Child Health. 1999;24:182-186. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Malekafzali H, Poureslami I. Survey of Health Indicators in Sistan & Baluchestan Province in Iran and the Border Areas of Afghanistan and Pakistan. Presented at the First Seminar of Analyzing the Obstacles and Effective Factors in Cultural and Educational Development of Sistan & Baluchestan and Its Borders; 1998.

- 32. Crystal D. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language. 2nd ed; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dail A. "Dictionary of Languages" Bloomsbury Publishing Inc, London, UK: Universal Language Resources; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 34. UNICEF. UNICEF Humanitarian Action: Afghanistan Crisis. November 2001; 2: 1-6.

- 35. Amartya S. The many faces of gender inequality. New Republic. 2001;225:35-41. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nierenberg D. Afghan women. World Watch. 2002;15:1-2. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Weiner M, Banuazizi A. Gender Inequality in the Islamic Republic of Iran: A Socio-Demography. In The State and Social Transformation in Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan. Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Poureslami I. Social, Cultural, and Environmental Determinants of Health Status of Women and Children in AIP Region (Borders between Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan). Presented at the Institute of Health Promotion Seminar; University of British Columbia; September 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Moghadam VM. Gender and National Identity: Women and Politics in Muslim Societies. London, UK: Zed Books; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Moghadam VM. Patriarchy and the politics of gender in modernizing societies: Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan. International Sociology. 1992;7:35-53. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kamguian A. Women in Afghanistan: What Next? Institute for Secularization of Islamic Society; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Miller LC, Timouri M, Wijnker J, Schaller JG. Afghan refugee children and mothers. Arch Pediatr Med. 1994;148:704-708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Djazayery A. FAO-Nutrition Country Profiles: Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan. 2002. FAO, Rome, Italy. Available at: http://www.fao.org/countryprofiles/index.asp?lang=en&iso3=IRN. Last accessed July 24, 2004.

- 44. Bartlett L, Sheps S, Povey G. Maternal Mortality in Afghanistan: Magnitude, Causes, Risk Factors and Preventability. Preliminary Findings, UNICEF-CDC November 2002. Presented at the HealthCare and Epidemiology Seminar, University of British Columbia; May 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Malekafzali H. Mortality from diarrhea among children under 5 in Iran. Eastern Mediterranean Region Health Journal. 1998;5:41-46. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rasekh Z, Manos M. Women's health and human rights in Afghanistan. JAMA. 1998;280:449-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. WHO-EMRO Document 56: First border meeting: Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan (AIP). Chabahar, Iran; July 2003.

- 48. Sheykhi MT. Proposals to Alleviate Poverty and Decrease Social Exclusion in Asia with Emphasis on Iran: A Sociological Appraisal. Presented at International Research Conference on Social Security; 2000; Helsinki, Finland; ,2000.

- 49. Oxfam International Advocacy Office. Humanitarian Situation in Afghanistan and on its Borders. Oxfam Briefing Paper No. 6. September 2001: 1-9.

- 50. United Nations Development Program. The Global Challenge: Goals and Targets. Millennium Development Goals. 2002: 1-12.

- 51. UN Secretary Council. Letter from Iran to the UN Secretary-General: Blockage of water flow in the Hirmand River. Relief Web. December 2002.

- 52.Van der Hoek W, Feenstra SG, Konradsen F. Availability of irrigation water for domestic use in Pakistan: its impact on prevalence of diarrhea and nutrition status of children. J Health Popul Nutr. 2002;20:77-84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Grima B. Women, Culture, and Health in Rural Afghanistan. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Moghadam VM. Modernizing Women: Gender and Social Change in the Middle East. Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner Publishers; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Stein J. Education is the Key to Women's Health and Security. Women's Health matters: Women & Social Conditions. Sunnybrook and Women's College Health Sciences Centre; March 2002.

- 56. Hlupekile Longwe S. Gender Equality and Women's Empowerment. Presented at the Working Seminar on Methods for Measuring Women's Empowerment in a Southern African Context; October 2001; Windhoek, Namibia.

- 57. Convention on the elimination of all forms of discrimination against women. In: Twenty-five Human Rights Documents. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 1994: 48-56. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Swarna J. Women, education and empowerment in Asia. Gender & Education. 1997;9:411-424. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Editorial. Can we promote equity when we promote health? Health Promotion International. 1997;12:97-98. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Jahan RA. Promoting health literacy: a case study in the prevention of diarrhea disease. Health Promotion International. 2000;15:285-291. [Google Scholar]

- 61. UNICEF Afghanistan. 2002 - Year in Review. Pishraft. January 2003 report.