Abstract

There is increasing evidence that genetic factors are associated with ischemic stroke, including multiple recent reports of association with the gene PDE4D, encoding phosphodiesterase 4D, on chromosome 5q12. Genetic studies of stroke are important but can be logistically difficult to perform. This article reviews the design of the Siblings With Ischemic Stroke Study (SWISS) and discusses problems in performing a sibling-based pedigree study where proband-initiated consent is used to enroll pedigree members. Proband-initiated enrollment optimizes privacy protections for family members, but it is associated with a substantial pedigree non-completion rate such that 3 to 4 probands must be identified to obtain one completed sibling pedigree. This report updates the progress of enrollment in the SWISS protocol, discusses barriers to pedigree completion and describes innovative approaches used by the SWISS investigators to enhance enrollment.

Keywords: Cerebral infarction, Ischemic stroke, Pedigree research, Proband, Recruitment, SWISS

Each year in the United States, about 500,000 patients have their first stroke and 200,000 patients have recurrent strokes. The estimated direct and indirect costs of stroke are $56.8 billion for 2005.1 There is intense interest in unraveling the genetic component of complex disorders like stroke. Monozygotic twins are 1.65-fold more likely to be concordant for stroke than dizygotic twins.2 In case-control studies, a family history of stroke increased the risk of stroke by 1.76-fold; in cohort studies, the risk of stroke increased by 1.30-fold.2

Although isolated candidate gene studies have generated conflicting results, a recent meta-analysis3 identified significant associations between ischemic stroke and polymorphisms in the genes for factor V Leiden, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, prothrombin and angiotensin-converting enzyme. The odds ratios for stroke for the significant polymorphisms ranged from 1.21 to 1.44. After analysis of 120 case-control studies encompassing 32 genes, Casas and colleagues3 concluded that common polymorphic variants in several genes, each exerting a modest effect, contribute to the risk of stroke.

THE SIBLINGS WITH ISCHEMIC STROKE STUDY (SWISS)

The human genome may contain chromosomal regions associated with ischemic stroke. SWISS aims to test this hypothesis through genome-wide scanning of DNA samples collected from sibling pairs who are concordant and discordant for stroke. The SWISS protocol has been published previously.4 Although there have been many affected-sibling-pair genetic studies for diverse and complex disorders, SWISS is the first multicenter affected-sibling-pair study of ischemic stroke. Investigators now have years of experience recruiting stroke-affected sibling pairs for SWISS. Here, we summarize the recruitment protocol, report on feasibility and pilot studies leading up to SWISS and describe interim results of the recruitment phase of the study.

Definition of Phenotype

Stroke is defined according to World Health Organization criteria5 as rapidly developing signs of a focal or global disturbance of cerebral function, with symptoms lasting at least 24 hours or leading to death with no apparent cause other than vascular origin. Patients are classified as having an ischemic stroke if computed tomographic or magnetic resonance imaging of the brain within 7 days of onset of symptoms identified the symptomatic cerebral infarct or failed to identify an alternative cause of the symptoms. Endophenotypes are defined according to the Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment criteria.6 Subtype diagnosis is made on the basis of available and relevant information obtained up to 3 months after the stroke.7

Study Population

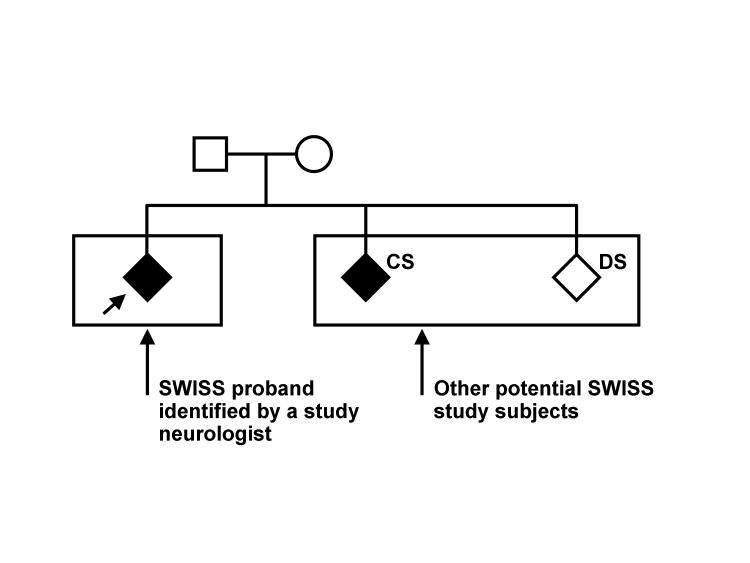

Three groups of subjects will be studied: probands, concordant siblings and discordant siblings. A typical SWISS pedigree is shown in figure 1▶.

Figure 1.

A typical SWISS pedigree. The proband is identified by the angled arrow. Squares represent men, circles represent women and diamonds represent study subjects (men and women). Stroke-affected members are shaded. CS, concordant sibling; DS, discordant sibling. Reproduced with permission from Meschia et al. The Siblings With Ischemic Stroke Study (SWISS) protocol. BMC Med Genet 2002;3:1.11882254 4 Copyright 2002 Meschia et al.

Probands

Probands are adult men and women who 1) have a diagnosis of at least one ischemic stroke confirmed by the study neurologist, 2) report having at least one living full sibling with a history of stroke and 3) are at least 18 years old at the time of enrollment in the study. If probands have had more than one ischemic stroke, the most recent is the proband index stroke. Probands are not excluded from the study for radiographic evidence of hemorrhagic transformation of an ischemic stroke.

Probands are not enrolled if any of the following conditions apply: 1) the index stroke is presumed to be iatrogenic, i.e., onset of symptoms occurred within 48 hours after an invasive cerebrovascular or cardiovascular procedure such as coronary artery bypass grafting, a catheter-based procedure on carotid or coronary arteries, carotid endarterectomy, heart valve surgery, or thoracic or thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair; 2) the index stroke is presumed due to vasospasm after nontraumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage, i.e., the onset of symptoms occurred within 60 days after the onset of a nontraumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage; 3) the index stroke is presumed due to an autoimmune condition, i.e., the patient has a history of brain biopsy proven central nervous system vasculitis; 4) the patient is known to have any of the following single-gene or mitochondrial disorders: cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy, Fabry disease, homocystinuria, mitochondrial encephalopathy with lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes, or sickle cell anemia; 5) the patient had a mechanical aortic valve or a mechanical mitral valve at the time of index stroke onset (this criterion was chosen because of the high likelihood that ischemic strokes are iatrogenic in such patients); or 6) the patient had untreated or actively treated bacterial endocarditis at the time of index stroke onset.

Concordant siblings

To be enrolled as a concordant sibling, the subject must have a full sibling enrolled as a proband in SWISS. The eligibility criteria for concordant siblings are identical to those of probands. Both proband and concordant siblings must be at least 18 years old at enrollment and both must meet the same definition of ischemic stroke. A central, genotype-blinded committee of study-appointed neurologists makes the diagnosis of ischemic stroke on the basis of medical record review.

Discordant siblings

Inclusion criteria for discordant siblings enrollment into SWISS are as follows: 1) the subject is 18 years old at enrollment, 2) the subject has two or more full siblings who each have had an ischemic stroke and are participating in the study, and 3) the subject reports no medical history of stroke or transient ischemic attack and denies having any stroke symptoms. Discordant siblings are evaluated using the Questionnaire for Verifying Stroke-Free Status (table 1▶).8–11 Discordant siblings are excluded if they are deemed unreliable historians in the opinion of the interviewer administering the questionnaire. This judgment is made on the basis of the interviewer’s overall impression of moderate or severe impairment of speech, language, hearing or memory.

Table 1.

Questionnaire for verifying stroke-free status8

| Medical history |

| Were you ever told by a physician that you had a stroke? |

| Were you ever told by a physician that you had a mini-stroke or transient ischemic attack? |

| Review of symptoms |

| Have you ever had sudden, painless weakness on one side of your body? |

| Have you ever had sudden numbness or a dead feeling on one side of your body? |

| Have you ever had sudden, painless loss of vision in one or both eyes? |

| Have you ever suddenly lost half of your vision? |

| Have you ever suddenly lost the ability to understand what people were saying? |

| Have you ever suddenly lost the ability to express yourself verbally or in writing? |

Timing of DNA sampling

DNA samples are obtained at the time of pedigree enrollment (when the proband and concordant sibling have signed the consent form, with or without a discordant sibling). If signed informed consent is obtained from a legally authorized patient representative, DNA can also be obtained from probands who are impaired by the stroke and unable to provide informed consent. However, a study-wide survey of investigators and coordinators performed during 2002 and 200312 showed that only 46% of sites had authorization from their institutional review boards (IRB) to use surrogate consent for enrolling probands.

DNA is not obtained from patients who suddenly die of stroke. While this may introduce survival bias, the 30-day case-fatality rate for ischemic stroke is about 5%.13 Survival bias is likely to have less influence in studies of ischemic stroke than, for example, in studies of cerebral hemorrhage.

Recruitment Goals

We aim to enroll at least 300 concordant sibling pairs (300 probands and 300 concordant siblings) and 200 discordant siblings for a total of 800 study subjects. Because not all concordant siblings will participate in our study, more than 300 probands will be enrolled to obtain DNA from 300 concordant sibling pairs.

RESULTS OF A FEASIBILITY STUDY

SWISS was planned with the assumption that most probands would be enrolled shortly after presenting for medical attention with stroke, typically in the inpatient setting. A prospective family history registry was established at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota and Jacksonville, Florida.14 A total of 310 probands were enrolled between January 1, 1999 and August 31, 2000. The family history of stroke, including biological parents and full siblings, was obtained by a systematic interview of the proband or, when necessary, a surrogate. The median age of probands was 75 years (range: 26 to 97 years). Forty-eight percent of probands were women, 75% had at least one living sibling (95% confidence interval [CI], 70% to 80%), 10% had at least one concordant (stroke-affected) living sibling (95% CI, 7% to 14%) and 2% had at least one concordant sibling living in the same city as the proband (95% CI, 1% to 4%).

On the basis of the feasibility study, we estimated that we needed to screen approximately 10 probands to find 1 potentially concordant living sibling. We anticipated that the 10:1 ratio of patients screened to enrolled was conservative because not every sibling who reportedly had a history of stroke would have a well-documented, symptomatic ischemic stroke, and probands could be misinformed about the medical history of some siblings. Furthermore, some siblings with a stroke history may have had a hemorrhagic stroke rather than an ischemic stroke. Lastly, of the siblings with a true history of ischemic stroke, only a portion would have accessible medical records and only a portion would agree to participate in a genetics study.

The feasibility study clearly demonstrated the problem of geographic dispersion of siblings. We needed a process where we could verify the sibling phenotype and collect DNA when the sibling did not live near the center enrolling the respective proband. Remote recruitment of siblings has its own challenges; it may be more difficult to convey the importance of participating in a study over the telephone or by mail when compared with investigators interacting face-to-face with potential study subjects.

INVESTIGATOR-INITIATED CONTACT OF SIBLINGS

Pilot testing of sibling-pair recruitment was performed at Mayo Clinic sites in Rochester, Minnesota; Jacksonville, Florida; and Scottsdale, Arizona from August 30, 1999 to February 21, 2000.15 The pilot study used investigator-initiated contact of siblings. After enrolling a proband, a letter was mailed to a potentially concordant sibling informing the sibling that he or she may be contacted by the study’s operations center. Information such as name and address from proband case report forms (sent from the local center to the operations center) was used to telephone siblings. The operations center obtained verbal consent from siblings and sent a request for medical information form and two copies of the informed consent form to the sibling. After the Request for Medical Information form and one copy of the Informed Consent form were signed and returned to the operations center, we obtained health records and verified stroke-affected status in potentially concordant siblings.

Nine unrelated probands (6 men and 3 women) were enrolled. Median age was 74 years (range: 57 to 79 years). The median time from onset of the index stroke to enrollment was 18 days (range: 7 to 127 days). There were 10 potentially concordant siblings among the 9 pedigrees. The operations center received signed request for medical information forms and medical records from 100% (10/10) and 90% (9/10) of the potentially concordant siblings, respectively. Review of the records confirmed concordance for stroke in at least one sibling for 66% (6/9) of the probands. None (0/10) of the siblings lived in the same city as the proband.

PROBAND-INITIATED CONTACT OF SIBLINGS

The SWISS Executive Committee opted to switch from investigator-initiated contact to proband-initiated contact of siblings. This change allowed the identification of potential pedigrees without breaching the privacy of individuals in the pedigree.16 In proband-initiated contact, the proband does not share personal health identifiers or contact information of family members directly with investigators. Instead, enrolled probands provide information about the study and contact information of investigators to their siblings. Family members interested in the study contact investigators directly, and those with no interest in the study are free to avoid contacting the investigators.

For several years, the Mayo Foundation IRB disallowed investigator-initiated contact of siblings of probands enrolled at Mayo Clinic. This policy was in effect during a time of increased concerns about potential risks to “third parties” related to family history research.17 A subsequent Mayo Foundation IRB policy shift permitted investigators to mail letters of invitation to proband siblings, provided that there was proband consent. This led SWISS to seek and ultimately secure permission for a protocol modification, where investigators could contact family members by telephone if no response was received within 4 weeks of the letter mailing. The Mayo Foundation IRB approved the protocol modification in September 2005.

The SWISS Executive Committee recognized that proband-initiated contact could have an adverse effect on pedigree recruitment. We reviewed proband-initiated recruitment of pedigrees when 371 probands were enrolled.18 The sibling response rate was 30.6% (105/343). Of the siblings who contacted the operations center, 96% (101/105) authorized further contact. It is not known whether the siblings fail to contact the coordinating center because probands do not provide siblings with study information or because siblings are not interested in participating in the study. We needed to enroll more than 3 probands to collect DNA from 1 complete pedigree. Median time from proband enrollment to pedigree DNA banking was 134 days.

STATUS OF RECRUITMENT

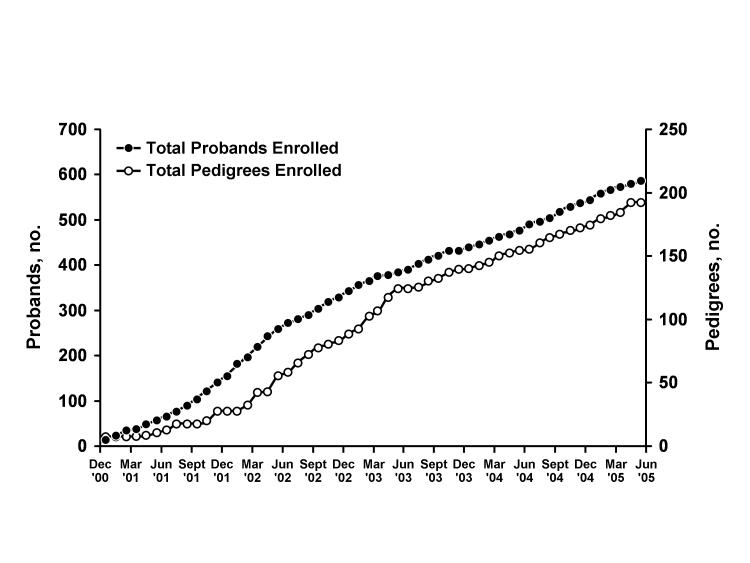

As of May 31, 2005, we have obtained DNA from 192 pedigrees. A total of 60% (116/192) of the pedigrees consist of a proband and one concordant sibling. A total of 38% (73/192) of the pedigrees consist of a proband, one concordant sibling and one discordant sibling. A total of 1% (2/192) of the pedigrees have more than one concordant sibling (one has two concordant siblings and one discordant sibling, the other has two concordant siblings and no discordant siblings). For one pedigree, DNA was collected from only one individual. The overall study-wide average recruitment rate has been 3.6 pedigrees per month. In 2005, the study-wide average recruitment rate has been 4.3 pedigrees per month (figure 2▶). The median age of DNA-donating probands is 67.4 years (mean, 66.3 years; range, 27 to 89 years). At the time of the index stroke, 5% (9/197) of probands were younger than 45 years, 18% (35/197) were younger than 55 years, and 41% (80/197) were younger than 65 years.

Figure 2.

Recruitment of probands and completed pedigrees in SWISS from December 2000 to June 2005. A pedigree is considered complete when DNA has been collected from a proband and at least one ischemic stroke-affected full sibling of the proband (i.e., one concordant sibling).

A recruitment goal of the study is to obtain a sample that is demographically representative of the North American population. Several efforts have been made to assure that case ascertainment is as complete as possible. Physician investigators and coordinators are continually reminded through monthly newsletters and annual investigator meetings to screen every patient with ischemic stroke encountered at their respective clinical sites. Furthermore, site payments are structured on a per-proband and per-pedigree basis, rather than as fixed salary support. The SWISS budget structure may encourage consecutive case ascertainment across sites.

To encourage participation in the study, sites are given study-specific brochures written in lay language that inform potential probands and their surrogates about the study. Study-specific posters are provided to advertise the study to patients and remind local investigators to screen potential participants. The Operations Committee has distributed a presentation to all principal investigators for use in educating physicians at their respective sites of the study. The presentation briefly outlines the objectives of SWISS and the eligibility criteria for probands.

The degree to which the enrolled proband population accurately represents the screened population of ischemic stroke patients treated at participating institutions is not precisely known. Maintenance of screening logs at all sites was not feasible because eligible probands constituted a low proportion of the screened patients. However, we compared the racial and ethnic composition of enrolled probands with all patients seen at the University of Virginia Health System (Charlottesville, Virginia), one of the SWISS sites with a higher enrollment rate. Table 2▶ shows that the racial composition of probands was comparable to the racial composition of the overall patient population at that site.

Table 2.

Racial composition of SWISS probands, patient population and local population

| White, % | African American, % | Asian, % | Native American, % | Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, % | Other, % | Multiracial, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SWISS probands* | 65.0 | 32.5 | 0 | 2.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| UVA patients (2002)† | 81 | 18 | <1 | NA | NA | <1 | NA |

| UVA patients (2004)† | 81 | 18 | 1 | NA | NA | <1 | NA |

| Charlottesville, Virginia (2000)‡ | 69.6 | 22.2 | 4.9 | 0.1 | 0 | 1 | 2.1 |

*First 40 probands consecutively enrolled at UVA.

†All UVA patients seen during the year indicated.

‡US Census data (2000).

NA, not available. (These census categories were not used at the time.)

SWISS, Siblings With Ischemic Stroke Study; UVA, University of Virginia Health System (Charlottesville, Virginia).

As of May 2005, there is greater racial diversity among all enrolled probands than among DNA-donating probands (DNA was collected from sibling pairs only after sibling stroke status was confirmed).19,20 Table 3▶ shows proband enrollment stratified by race and ethnicity for all probands and the subset of probands who donated DNA. Our experience with enrolling sibling pairs implies that minority patients who are informed about the research in a face-to-face interview with on-site study staff are more likely to appreciate the importance of the research aims and be reassured of the minimal risk of participation than individuals who are first informed of the study by relatives. Proband-initiated contact likely compounds a preexisting reluctance among minority populations to have genetic testing.21

Table 3.

Racial and ethnic composition of all probands and DNA-donating probands*

|

All probands |

DNA-donating probands |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | ||

| Race | |||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 447 | 77 | 180 | 93 | |

| African American | 22 | 4 | 7 | 3.5 | |

| Other | 111 | 19 | 7 | 3.5 | |

| Total | 580 | 100 | 194 | 100 | |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Hispanic | 20 | 3 | 3 | 2 | |

| Non-Hispanic | 560 | 97 | 188 | 98 | |

| Total | 580 | 100 | 191 | 100 | |

* Diagnosis of ischemic stroke was confirmed for at least one living sibling before DNA was donated.

CREATION OF A GENETIC RESOURCE

After obtaining informed consent from all members of the enrolling pedigree, blood from each participant was collected and shipped to the Coriell Institute for Medical Research (Camden, New Jersey) by overnight courier service and processed within 1 to 8 days after venipuncture (mean: 1.8 days). Cell lines from SWISS participants were established from freshly isolated lymphocytes using standard Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) transformation protocols that included cell separation by gradient centrifugation and lymphocyte growth enhancement by the mitogen phytohemagglutinin.19

EBV is a human herpesvirus that interacts with immunocompetent cells carrying the EBV receptor. EBV is used to transform human B cells into continuously propagating lymphoblastoid cell lines in vitro.22 EBV-transformed lymphoblast cell lines are generally robust and long-lived in culture, however, they typically are not truly immortal and most EBV-transformed cell lines do not have more than 160 population doublings.23,24 Nevertheless, appropriate maintenance of cell lines should assure a practically unlimited supply of genetic material from most EBV-transformed cells.

Since EBV transformation is widely used to generate permanent cell lines, it is important to know if the virus affects the genome of the transformed cells. Analyses of point mutations and deletions in several genes have shown that the mutations observed in lymphocytes are identical to those in EBV-transformed lymphoblastoid cells, and these mutations are stable through five 10-fold expansions of the cell lines.25 However, for trinucleotide-repeat mutations, which can be unstable in vivo,26 the stability of disease mutations in the transformed cell lines was similar to the stability before transformation.25 Furthermore, a marked decrease in DNA methylation observed after transformation suggests that a variable demethylation process was induced.27 Although trinucleotide repeats may be subject to mutation or altered methylation, it is assumed that the EBV-transformed cell lines generally provide a stable resource for genetic material.

SWISS cell lines were established and grown without antibiotics. For a transformation to be considered successful, the cell line had to be free of contamination from bacteria, fungi and mycoplasma, and it must be viable after cryopreservation. The transformation success rate was determined for 360 individuals affected with stroke and 68 unaffected siblings. In total, 317 non-contaminated, viable cell lines were obtained (317/360, success rate = 88.0%). Sixty-three cell lines were established from the unaffected siblings (63/68, success rate = 92.6%). The difference in success rates could not be attributed to the multiple variables that might affect transformation, e.g., time between venipuncture and initiation of processing, mean age at sampling and volume of blood. Of note, a considerable portion (15.1%) of samples from affected individuals required more than 60 days for successful transformation when compared with samples from unaffected siblings (6.3%). This might be due to differences in the biology of the cells or the medication regimen of each individual.

The success rates presented above were determined by one transformation attempt for each subject. Because additional aliquots of isolated cryopreserved lymphocytes were available for multiple transformations, cell lines were established with nearly 100% efficiency. Thus, we have created a renewable source of genetic material from SWISS participants for future studies.

EFFORTS TO ENHANCE RECRUITMENT

As stated above, there is considerable attrition between enrolling a proband at a local center and obtaining DNA from a pedigree. It is also apparent that the recruitment rates at participating clinical sites are not proportional to the volume of stroke patients seen in clinical practice. To increase the rate of pedigree recruitment, the Operations Committee will try to foster higher recruitment rates at the clinical sites. Therefore, it is important for SWISS to increase its visibility among physicians and coordinating staff at participating centers.

Larger stroke centers are likely to have several concurrent treatment and prevention studies for patients with ischemic stroke. Participation in a therapeutic trial does not preclude patient participation in SWISS. However, investigators may be reluctant to enroll a patient in two concurrent studies for fear that the process of informed consent or compliance with the protocols might be compromised.

SWISS has no eligibility criterion for probands based on time from onset of stroke to enrollment. This is in contradistinction to many stroke prevention studies that have an onset-to-enrollment time window of several weeks28 and in sharp contradistinction to acute ischemic stroke treatment trials that have an onset-to-enrollment window of only a few hours.29 Because SWISS has no onset-to-enrollment time window, probands may be enrolled long after routine acute care and rehabilitation services have ceased.

SWISS is increasing direct-to-patient advertising of the study, encouraging patients to electively present at a clinical site for screening. Advertisements and so-called advertorials will appear in patient-centered periodicals published by nonprofit stroke advocacy groups. SWISS was recently added to the Web site maintained by the National Institutes of Health (http://ClinicalTrials.gov) which provides contact information for investigators and coordinators at many participating clinical sites; interested patients can learn more about the study from investigators in their area. With weekly telephone calls to site coordinators, the SWISS Recruitment Subcommittee reviews site-specific recruitment tools for lower-recruiting sites. Another strategy to increase recruitment involves community action by the study coordinators. By participating in local health fairs and community health awareness presentations, coordinators will share information about stroke prevention and participation in SWISS.

SWISS is also increasing the number of clinical sites where probands are screened and enrolled. In January 2005, the SWISS Recruitment Subcommittee asked current investigators for recommendations of new sites and new investigators to improve patient recruitment. This inquiry resulted in the identification of 21 new sites. In February 2005, 64 clinics (not already participating in SWISS) were identified as primary stroke centers on the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations Web site for disease-specific certifications. The 85 sites were invited to participate in SWISS, and a positive response was received from 38 centers (45%). Currently, 42% (16/38) have contracts to participate in the study and are in the process of getting study approval from their individual IRBs to begin enrolling participants. Although the primary purpose of developing stroke centers was to improve patient outcomes through greater standardization of care and greater compliance with evidence-based guidelines,30,31 the SWISS experience suggests that the creation of certified stroke centers has also created a unique opportunity to further clinical research in stroke. The SWISS Operations Committee now uses a site selection survey to help prioritize sites targeted to join the study. The survey inquires about the number of stroke patients seen per year and the demographic characteristics of the patient population. The Operations Committee is interested in enriching the consortium of sites that see patients from predominantly minority populations. Appendix A lists all the currently participating centers.

CONCLUSIONS

There is increasing evidence that genetic factors are associated with ischemic stroke, making genetic studies of stroke such as SWISS a high priority. The sibling-pair design of SWISS, including analysis of concordant and discordant siblings, should provide sufficient data to identify chromosomal regions that are associated with ischemic stroke. The preliminary evidence indicates that the design of the SWISS trial is feasible, but it is logistically challenging because siblings frequently do not live near each other. Thus, the SWISS protocol was expanded to many centers across the United States and includes the aim of collecting a representative sample of ischemic stroke patients.

After SWISS was initiated, interpretation of privacy regulations by the Mayo Foundation IRB led to a protocol change requiring proband-initiated contact. These changes have been associated with markedly slowed recruitment of pedigrees, primarily because of sibling nonresponse. To date, three or more probands have been enrolled for every one completed pedigree. Proband enrollment has generally been representative of the racial distribution of the ischemic stroke population, but pedigree completion is less likely to occur in minority groups. The reasons for this are unclear but may include minority patients being less trustful of the medical and scientific community, the perception among minority populations of being studied rather than being included in the process of discovery, or the perception of lack of cultural sensitivity among investigators.32 There may also be disinclination in some minority populations specific to participating in research that includes genetic testing.21

The SWISS investigators have responded to these challenges, and recruitment continues at a steady pace. We anticipate that enrollment will be complete by 2008, and final genetic analyses will be completed thereafter.

APPENDIX A

SWISS Investigative Team

Executive Committee: James F. Meschia, chair; Thomas G. Brott, Robert D. Brown, Jr, Brett Kissela, John Hardy, Stephen S. Rich. Statistical Center: Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Stephen S. Rich, director; W. Mark Brown. DNA Repository: Coriell Institute for Medical Research, Camden, New Jersey. Jeanne Beck, PhD, director. Data and Site Management: Mayo Alliance for Clinical Trials, Rochester, Minnesota. Tammy S. Olson, clinical trials assistant; Jay B. Doughty, project manager; Hattie M. Hanert, RN, senior clinical research associate; Pamela S. Neumann, data management director; Karen Johnson, regulatory affairs director.

Centers and Investigators Listed by Proband Enrollment as of May 25, 2005

Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota (probands enrolled, 52): Principal investigator (PI): Robert D. Brown, Jr, MD; coordinator: Colleen S. Albers, RN; subinvestigators (SI): George W. Petty, MD; Eelco F. M. Wijdicks, MD; Irene Meissner, MD; Bruce A. Evans, MD; Kelly D. Flemming, MD; Edward M. Manno, MD; Jimmy R. Fulgham, MD; David O. Wiebers, MD.

Shands HealthCare, affiliated with the University of Florida, Jacksonville, Florida (probands enrolled, 40): PI: Scott Silliman, MD; coordinator: Barbara Quinn, RN; Cicely Bryant.

University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, Ohio (probands enrolled, 39): PI: Brett Kissela, MD; coordinator: Kathleen Alwell, RN; SI: Joseph Broderick, MD; Daniel Woo, MD; Daniel Kanter, MD; Dawn Kleindorfer; Alexander Schneider, MD; Matthew Flaherty, MD.

University of Virginia Health System, Charlottesville, Virginia (probands enrolled, 39): PI: Bradford Worrall, MD, MSc; coordinator: Martha Davis, RN; SI: E. Clarke Haley, Jr, MD; Karen Johnston, MD, MSc; Jaclyn van Wingerden.

Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Florida (probands enrolled, 36): PI: Thomas G. Brott, MD; coordinator: Jacob Rosenberg, CRC; SI: James F. Meschia, MD; Frank A. Rubino, MD; Benjamin H. Eidelman, MD.

Mercy Ruan Neurology Clinic, Des Moines, Iowa (probands enrolled, 33): PI: Michael Jacoby, MD; coordinator: Judi Greene, RN; SI: Bruce Hughes, MD; Randall Hamilton, MD; Paul Babikian, MD; Mark Puricelli, DO.

Neurological Associates, Inc, Richmond, Virginia (probands enrolled, 31): PI: Francis McGee, Jr, MD; coordinator: Sharon McQueen-Goss, RN; Janet McGee, CCRC; SI: Stephen Thurston, MD; Thomas Smith, MD; Robert White, MD; Philip Davenport, MD; John Brush, MD; Susanna Mathe, MD; Robert Cohen, MD; J. Kim Harris, MD; John O’Bannon III, MD; John Blevins, MD.

Mercy General Hospital, Sacramento, California (probands enrolled, 16): PI: Paul Akins, MD, PhD; coordinator: Deidre Wentworth, RN.

Main Line Health Stroke Program, Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania (probands enrolled, 16): PI: Gary Friday, MD; coordinator: Angela Whittington-Smith, RN.

Centre Hospitalier Affilie Universitaire de Quebec, Quebec City, Province of Quebec, Canada (probands enrolled, 14): PI: Ariane Mackey MD; coordinator: Annette Hache, RN; Sophie Dube, RN; SI: Steve Veireault, MD.

Kaleida Stroke Care Center, Millard Fillmore Gates Circle Hospital, Buffalo, New York (probands enrolled, 14): PI: F. E. Munschauer, MD; coordinator: Kathleen Wrest, MLS; SI: Peterkin Lee-Kwen, MD.

Luther Midelfort Hospital, Eau Claire, Wisconsin (probands enrolled, 13): PI: Felix Chukwudelunzu, MD; coordinator: Tonya Kunz, RN; Karen Snobl, RN; SI: James Bounds, MD; Rae Hanson, MD; David Nye, MD; Donn Dexter, MD.

Maine Medical Center, Portland, Maine (probands enrolled, 12): PI: John Belden, MD; coordinator: Diane Diconzo-Fanning, RN; SI: Paul Muscat, MD.

Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Arizona (probands enrolled, 12): PI: David W. Dodick, MD; coordinators: Erica L. Boyd, RN; Rebecca I. Rush, RN; Gail R. LeBrun, RN; Nadine F. Lendzion, RN; Barbara B. Cleary, RN; SI: Bart M. Demaerschalk, MD.

Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina (probands enrolled, 11): PI: David Lefkowitz, MD; coordinators: Jean Satterfield, RN; Elizabeth Westerberg, CCRC; SI: Charles Tegeler IV, MD; Patrick Reynolds, MD.

Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (probands enrolled, 10): PI: Scott Kasner, MD; coordinator: Jessica Clarke, RN; SI: David S. Liebeskind, MD; Brett L. Cucchiara, MD; Michael L. McGarvey, MD; Steven R. Messe, MD; Robert A. Taylor, MD.

University of Maryland, Baltimore, Maryland (probands enrolled, 10): PI: Steven Kittner, MD; coordinators: Mary J. Sparks; SI: John Cole, MD.

Stroke Prevention and Atherosclerosis Research Centre, London, Ontario, Canada (probands enrolled, 10): PI: David Spence, MD; coordinator: Rose Freitas; SI: Claudio Munoz, MD.

University of South Alabama, Mobile, Alabama (probands enrolled, 10): PI: Richard Zweifler, MD; coordinators: Robin Yunker, RNC, MSN; Mel Parnell, RN, BSN; SI: Ivan Lopez, MD; M. Asim Mahmood, MD.

Hôpital Charles LeMoyne, Greenfield Park, Province of Quebec, Canada (probands enrolled, 9): PI: Leo Berger, MD; coordinators: Martine Maineville; Denise Racicot.

University of Iowa Hospital, Iowa City, Iowa (probands enrolled, 9): PI: Patricia Davis, MD; coordinator: Jeri Sieren, RN; SI: Harold P. Adams, Jr, MD.

Metro Health Medical Center, Cleveland, Ohio (probands enrolled, 9): PI: Joseph Hanna, MD; coordinators: Alice Liskay, RN; Joan Kappler, RN; Dana Simcox, RN; SI: Marc Winkelman, MD; Nimish Thakore, MD, DM.

Cleveland Clinic Florida, Weston, Florida (probands enrolled, 9): PI: Virgilio Salanga, MD; coordinators: Anupama Podichetty, MD; Jose Alvarez, MD; SI: Eduardo Locatelli, MD; Nestor Galvez-Jimenez, MD; Efrain Salgado, MD.

Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri (probands enrolled, 8): PI: Jin-Moo Lee, MD, PhD; coordinator: Denise Shearrer, RMA, BS; SI: Abdullah Nassief, MD.

Helen Hayes Hospital, West Haverstraw, New York (probands enrolled, 5): PI: Laura Lennihan, MD; coordinator: Laura Tenteromano, RN.

University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, Dallas, Texas (probands enrolled, 8): PI: D. Hal Unwin, MD; coordinator: J. Greggory Wright, BS; SI: Dion Graybeal, MD; Mark Johnson, MD; Mounzer Kassab, MD.

University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin (probands enrolled, 7): PI: Robert Dempsey, MD; coordinator: Pam Winne; SI: George Newman, MD; Douglas Dulli, MD; Madeleine Geraghty, MD.

Marshfield Clinic, Marshfield, Wisconsin (probands enrolled, 7): PI: Percy Karanjia, MD; coordinator: Kathy Mancl, CCRC; SI: Kenneth Madden, MD.

Inova Fairfax Hospital, Church Falls, Virginia (probands enrolled, 7): PI: Paul Nyquist, MD; coordinator: Barbara Farmer, RN, MSN.

Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia (probands enrolled, 7): PI: Barney Stern, MD; coordinator: Betty Jo Shipp, RN; SI: Michael Frankel, MD; Marc Chimowitz, MD; Owen Samuels, MD.

University of California, Davis School of Medicine, Sacramento, California (probands enrolled, 7): PI: Piero Verro, MD; coordinator: Shari Nichols.

Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, Indiana (probands enrolled, 7): PI: Linda Williams, MD; SI: Askiel Bruno, MD; William Jones, MD.

East Bay Region Associates in Neurology, Berkeley, California (probands enrolled, 6): PI: Brian Richardson, MD; coordinator: Lauren McCormick.

Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio (probands enrolled, 6): PI: Andrew Slivka, MD; coordinator: Peggy Notestine, CCRC; SI: Yousef Mohammad, MD.

Florida Neurovascular Institute, Tampa, Florida (probands enrolled, 5): PI: Erfan Albakri, MD; coordinators: Taryn Chauncey, RN; Judy Jackson; Mary Katherine Taylor, ARNP.

Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (probands enrolled, 5): PI: Rodney Bell, MD; coordinator: Lisa Bowman, MNS, CRNP, CNRN; SI: David G. Brock, MD; Carissa Pineda, MD.

Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut (probands enrolled, 3): PI: Mark Gorman, MD; coordinator: Janet Halliday, RN, BS.

Scripps Clinic, La Jolla, California (probands enrolled, 4): PI: Mary Kalafut, MD; coordinator: Carmen James, RN; Joy Reyes.

University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky (probands enrolled, 4): PI: L. Creed Pettigrew, MD; coordinator: Deborah Taylor, MS; SI: Stephen Ryan, MD; Anand G. Vaishnav, MD.

University of California Los Angeles Stroke Center, Los Angeles, California (probands enrolled, 4): PI: Jeffery Saver, MD; coordinator: Gina Paek, BA; SI: Bruce Ovbiagele, MD; Scott Selco, MD; Venkatakrishna Rajajee, MD.

Field Neurosciences Institute, Saginaw, Michigan (probands enrolled, 3): PI: Faith Abbott, MD; coordinator: Richard Herm, RN, BSN, CEN; SI: Malcolm Field, MD; Debasish Mridha, MD.

Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, South Carolina (probands enrolled, 3): PI: Timothy Carter, MD.

University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, Illinois (probands enrolled, 3): PI: Cathy Helgason, MD; coordinator: Joan N. Martellotto, RN, PhD.

Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Baltimore, Maryland (probands enrolled, 3): PI: Rafael Llinas, MD; coordinator: Janice Alt; SI: Christopher Earley, MD.

University of California San Diego Stroke Center, San Diego, California (probands enrolled, 3): PI: Patrick Lyden, MD; coordinators: Nancy Kelly, RN; Janet Werner, RN; SI: Christy Jackson, MD; Thomas Hemmen, MD; Brett Meyer, MD.

Royal University Hospital, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada (probands enrolled, 3): PI: Ali Rajput, MD; coordinator: Theresa Shirley, RN; SI: Alexander Rajput, MD.

Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois (probands enrolled, 3): PI: Sean Ruland, DOMD; coordinator: Karen Whited, RN; SI: Michael Schneck, MD; Michael Sloan, MD; Phillip Gorelick, MD, MPH.

Chattanooga Neurology Associates, Chattanooga, Tennessee (probands enrolled, 3): PI: Thomas Devlin, MD; coordinators: Patty Wade-Hardie, RN; Tammy Owens, RN; SI: Adele Ackell, MD; Sharon Farber, MD; Ravi Chander, MD; G. Hagan Jackson, MD; Kadrie Hytham, MD; Bruce Kaplan, MD; David Rankine, MD.

Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science, Los Angeles, California (probands enrolled, 1): PI: Lowell Nelson, PhD; coordinators: Marcia Montenegro, RN; Derek Knight.

Syracuse VA Medical Center, Syracuse, New York (probands enrolled, 1): PI: Antonio Culebras, MD; coordinator: Therese Dean, RN.

Rhode Island Hospital, Providence, Rhode Island (probands enrolled, 1): Janet Wilterdink, MD; coordinator: Carol Cirillo, RN.

Disclaimer: Portions of this manuscript were published in Meschia JF, Brown RD Jr, Brott TG, Chukwudelunzu FE, Hardy J, Rich SS. The Siblings with Ischemic Stroke Study (SWISS) protocol. BMC Med Genet 2002;3:1. Epub 2002 Feb 12.

Grant Support: SWISS is supported by grant 5R01NS039987-05 from the United States National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

References

- 1.American Stroke Association, Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics —2005 Update. American Heart Association Web site. Available at: http://www.americanheart.org/downloadable/heart/1105390918119HDSStats2005Update.pdf. Accessed November 17, 2005.

- 2.Flossmann E, Schulz UG, Rothwell PM. Systematic review of methods and results of studies of the genetic epidemiology of ischemic stroke. Stroke 2004;35:212–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casas JP, Hingorani AD, Bautista LE, Sharma P. Meta-analysis of genetic studies in ischemic stroke: thirty-two genes involving approximately 18,000 cases and 58,000 controls. Arch Neurol 2004;61:1652–1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meschia JF, Brown RD Jr, Brott TG, Chukwudelunzu FE, Hardy J, Rich SS. The Siblings With Ischemic Stroke Study (SWISS) protocol. BMC Med Genet 2002;3:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO MONICA Project Principal Investigators. The World Health Organization MONICA Project (monitoring trends and determinants in cardiovascular disease): a major international collaboration. J Clin Epidemiol 1988;41:105–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adams HP Jr, Bendixen BH, Kappelle LJ, Biller J, Love BB, Gordon DL, Marsh EE 3rd. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment. Stroke 1993;24:35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Madden KP, Karanjia PN, Adams HP Jr, Clarke WR. Accuracy of initial stroke subtype diagnosis in the TOAST study. Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment. Neurology 1995;45:1975–1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meschia JF, Brott TG, Chukwudelunzu FE, Hardy J, Brown RD Jr, Meissner I, Hall LJ, Atkinson EJ, O’Brien PC. Verifying the stroke-free phenotype by structured telephone interview. Stroke 2000;31:1076–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones WJ, Williams LS, Meschia JF. Validating the Questionnaire for Verifying Stroke-Free Status (QVSFS) by neurological history and examination. Stroke 2001;32:2232–2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meschia JF, Lojacono MA, Miller MJ, Brott TG, Atkinson EJ, O’Brien PC. Reliability of the questionnaire for verifying stroke-free status. Cerebrovasc Dis 2004;17:218–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castillo PR, Brott TG, Alvarez S, Meschia JF. Creation of a bilingual Spanish-English version of the Questionnaire for Verifying Stroke-free Status. Neuroepidemiology 2004;23:236–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Worrall BB, Chen DT, Brown RD Jr, Brott TG, Meschia JF; SWISS. A survey of the SWISS researchers on the impact of sibling privacy protections on pedigree recruitment. Neuroepidemiology 2005;25:32–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hartmann A, Rundek T, Mast H, Paik MC, Boden-Albala B, Mohr JP, Sacco RL. Mortality and causes of death after first ischemic stroke: the Northern Manhattan Stroke Study. Neurology 2001;57:2000–2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meschia JF, Brown RD Jr, Brott TG, Hardy J, Atkinson EJ, O’Brien PC. Feasibility of an affected sibling pair study in ischemic stroke: results of a 2-center family history registry. Stroke 2001;32:2939–2941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meschia JF, Brott TG, Hardy J, Brown RD, Dodick DW, Cornwell KB. Genome-wide screen for stroke: pilot testing in the Siblings With Ischemic Stroke Study (SWISS). J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2000;9:276–281. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Worrall BB, Chen DT, Meschia JF. Ethical and methodological issues in pedigree stroke research. Stroke 2001;32:1242–1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wadman M. US geneticists encouraged to play by the book. Nature 2000;404:530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen DT, Worrall BB, Brown RD Jr, Brott TG, Kissela BM, Olson TS, Rich SS, Meschia JF; SWISS Investigators. The impact of privacy protections on recruitment in a multicenter stroke genetics study. Neurology 2005;64:721–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beck JC, Beiswanger CM, John EM, Satariano E, West D. Successful transformation of cryopreserved lymphocytes: a resource for epidemiological studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2001;10:551–554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doyle A, Griffiths JB. Mammalian cell culture: essential techniques. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons; 1997.

- 21.Armstrong K, Micco E, Carney A, Stopfer J, Putt M. Racial differences in the use of BRCA1/2 testing among women with a family history of breast or ovarian cancer. JAMA 2005;293:1729–1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pope JH, Horne MK, Scott W. Transformation of foetal human leukocytes in vitro by filtrates of a human leukaemic cell line containing herpes-like virus. Int J Cancer 1968;3:857–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sugimoto M, Furuichi Y, Ide T, Goto M. Incorrect use of “immortalization” for B-lymphoblastoid cell lines transformed by Epstein-Barr virus. J Virol 1999;73:9690–9691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sugimoto M, Ide T, Goto M, Furuichi Y. Reconsideration of senescence, immortalization and telomere maintenance of Epstein-Barr virus-transformed human B-lymphoblastoid cell lines. Mech Ageing Dev 1999;107:51–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bernacki SH, Beck JC, Stankovic AK, Williams LO, Amos J, Snow-Bailey K, Farkas DH, Friez MJ, Hantash FM, Matteson KJ, Monaghan KG, Muralidharan K, Pratt VM, Prior TW, Richie KL, Levin BC, Rohlfs EM, Schaefer FV, Shrimpton AE, Spector EB, Stolle CA, Strom CM, Thibodeau SN, Cole EC, Goodman BK, Stenzel TT. Genetically characterized positive control cell lines derived from residual clinical blood samples. Clin Chem 2005;51:2013–2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bowater RP, Wells RD. The intrinsically unstable life of DNA triplet repeats associated with human hereditary disorders. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol 2001;66:159–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonilla V, Sobrino F, Lucas M, Pintado E. Epstein-Barr virus transformation of human lymphoblastoid cells from patients with fragile X syndrome induces variable changes on CGG repeats size and promoter methylation. Mol Diagn 2003;7:163–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mohr JP, Thompson JL, Lazar RM, Levin B, Sacco RL, Furie KL, Kistler JP, Albers GW, Pettigrew LC, Adams HP Jr, Jackson CM, Pullicino P; Warfarin-Aspirin Recurrent Stroke Study Group. A comparison of warfarin and aspirin for the prevention of recurrent ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1444–1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alexandrov AV, Molina CA, Grotta JC, Garami Z, Ford SR, Alvarez-Sabin J, Montaner J, Saqqur M, Demchuk AM, Moye LA, Hill MD, Wojner AW; CLOTBUST Investigators. Ultrasound-enhanced systemic thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 2004;351:2170–2178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Camilo O, Goldstein LB. Lower stroke-related mortality in counties with stroke centers: North Carolina Stroke Facilities Survey. Neurology 2005;64:762–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kidwell CS, Shephard T, Tonn S, Lawyer B, Murdock M, Koroshetz W, Alberts M, Hademenos GJ, Saver JL. Establishment of primary stroke centers: a survey of physician attitudes and hospital resources. Neurology 2003;60:1452–1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Herring P, Montgomery S, Yancey AK, Williams D, Fraser G. Understanding the challenges in recruiting blacks to a longitudinal cohort study: the Adventist health study. Ethn Dis 2004;14:423–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]