Abstract

The viability of lactic acid bacteria in frozen, freeze-dried, and air-dried forms is of significant commercial interest to both the dairy and food industries. In this study we observed that when prestressed with either heat (50°C) or salt (0.6 M NaCl), Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 (also known as DR20) showed significant (P < 0.05) improvement in viability compared with the nonstressed control culture after storage at 30°C in the dried form. To investigate the mechanisms underlying this stress-related viability improvement in L. rhamnosus HN001, we analyzed protein synthesis in cultures subjected to different growth stages and stress conditions, using two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and N-terminal sequencing. Several proteins were up- or down-regulated after either heat or osmotic shock treatments. Eleven proteins were positively identified, including the classical heat shock proteins GroEL and DnaK and the glycolytic enzymes glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, lactate dehydrogenase, enolase, phosphoglycerate kinase, and triose phosphate isomerase, as well as tagatose 1,6-diphosphate aldolase of the tagatose pathway. The phosphocarrier protein HPr (histidine-containing proteins) was up-regulated in cultures after the log phase irrespective of the stress treatments used. The relative synthesis of an ABC transport-related protein was also up-regulated after shock treatments. Carbohydrate analysis of cytoplasmic contents showed higher levels (20 ± 3 μg/mg of protein) in cell extracts (CFEs) derived from osmotically stressed cells than in the unstressed control (15 ± 3 μg/mg of protein). Liquid chromatography of these crude carbohydrate extracts showed significantly different profiles. Electrospray mass spectrometry analysis of CFEs revealed, in addition to normal mono-, di-, tri-, and tetrasaccharides, the presence of saccharides modified with glycerol.

Certain species of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium are known probiotics that are extensively used in yogurts, dietary adjuncts, and other health-related products (4). By definition, probiotics are “ live microorganisms which when administered in adequate amounts confer a health benefit on the host” (16). The probiotic strain Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 (also known as DR20) has been characterized by a polyphasic approach using microbiological and molecular biological methods. The probiotic properties, such as ability to withstand acid and bile as well as the ability to adhere to human intestinal epithelial cells, have been described (41, 21). Further, L. rhamnosus HN001 has been shown to enhance natural and acquired immunity in healthy mice (19). In addition, a genome sequencing initiative for this strain is in progress (34).

The industrial preservation of lactobacilli involves processes such as freezing, freeze-drying, and air-drying. These processes can result in structural and physiological injury to the bacterial cells, resulting in substantial loss of viability. Initial investigations carried out on bacteria such as Escherichia coli have demonstrated that they possess an inherent ability to adapt to unfavorable environments by the induction of various general and specific stress responses. The survival of these bacteria under adverse conditions is frequently enhanced by these mechanisms. Different responses to different stress treatments (e.g., heat, low pH, osmotic shock, etc.) have been reported, and the heat shock response has been studied extensively (for reviews, see references 25 and 39). These stress responses are characterized by the transient induction of general and specific proteins and by physiological changes that generally enhance an organism's ability to withstand more adverse environmental conditions (1). In the case of osmotic stress, the significant physiological changes reported in bacteria include the induction of stress proteins as well as the accumulation of compatible solutes such as betaine, carnitine, and trehalose (8, 28, 35, 49).

There are only a few reports describing the physiological stress responses in lactic acid bacteria (LAB), particularly Lactobacillus species (5, 22, 32, 46, 48). Further, there is a paucity of information describing the physiological mechanisms underlying the stress-induced improvement in the survival of LAB in relation to industrial processing and storage conditions. To our knowledge, this is the first study describing the stress responses of L. rhamnosus in relation to viability and industrial processes. In this investigation, we used the analysis of two-dimensional (2D) protein gels combined with the identification of stress proteins by N-terminal sequencing to provide the first insights into the stress response of L. rhamnosus HN001. We have also analyzed the cell extracts (CFEs) for changes in carbohydrate profile in response to stress treatments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strain.

L. rhamnosus HN001 was obtained from the Culture Collection of the Fonterra Research Centre (earlier known as New Zealand Dairy Research Institute), Palmerston North, New Zealand. The number of subcultures used in this study was minimized by maintaining frozen stocks. All the experiments were conducted using the subcultures from the same frozen stock. The cultures were routinely grown in MRS broth (11) at 37°C.

Heat shock and growth characteristics of L. rhamnosus HN001.

The growth of L. rhamnosus HN001 was monitored by absorbance at 610 nm (OD610). Growth was initiated at 37°C, and when the OD610 reached 0.4 to 0.5, the cultures were transferred to water baths maintained at 45, 50, 55, and 60°C for 30 min. The time taken to attain the required shock temperature was less than 3 min. At the end of 10 min, the cultures were restored back to a water bath maintained at 37°C. Growth was further monitored until the cells reached the stationary phase.

Osmotic shock and growth characteristics of L. rhamnosus HN001.

L. rhamnosus HN001 was grown in MRS broth at 37°C, and when the OD610 reached 0.7 to 0.8, the cells were harvested by centrifugation (6,500 × g, 10 min, 4°C) and resuspended in MRS broth containing 0.0, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, or 0.7 M NaCl. Further growth was monitored to assess the effect of osmotic shock on the growth pattern. The osmolality of the MRS broth after the addition of salt was monitored with a vapor pressure osmometer (Wescor Inc., Logan, Utah).

Storage stability of dried L. rhamnosus HN001 cultures.

L. rhamnosus HN001 was grown in 1.5-liter lots in MRS broth. When the growth reached the mid-log phase (OD610 of about 0.7), heat shock (at 50°C) was applied as described above and the culture was immediately chilled and harvested by centrifugation (6,500 × g, 10 min, 4°C). The heat shock (at 50°C) was also given to stationary-phase cultures (after 16 h of growth [OD610, ∼1.6]) of L. rhamnosus HN001. Osmotic shock (0.6 M NaCl) was applied at mid-log phase, and growth was continued until the stationary phase. For each experiment four individual aliquots of MRS broth cultures were inoculated with identical inoculum levels (for heat shock at log and stationary phases, osmotic shock, and a nonshocked control) and grown under identical conditions. At the end of each treatment, the cells were harvested and the cell pellets obtained were reconstituted in chilled 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.5. The fluid bed drying was carried out at an inlet air temperature of 40°C and an outlet air temperature of 20 to 22°C with a drier from Glatt Air Techniques, Inc. (Ramsey, N.J.). The powders were stored in plastic containers at 30°C for about 4 months. The viable counts were determined at intervals on MRS agar by standard procedures. The paired t test was used to determine the statistical significance with Sigma plot version 4.01 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ill.).

Radiolabeling and preparation of CFEs.

Radiolabeling of shock proteins was carried out by using [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, N.J.). In the case of heat shock, radiolabeling was carried out just (3 min) after the shock treatment (at 50°C) during the mid-log phase (OD610, ∼0.7) as well as at the stationary phase (OD610, ∼1.6) of growth. In the case of osmotic shock, radiolabeling was carried out at the mid-log phase (OD610, ∼0.7) just (3 min) after transfer of the cells into MRS broth containing 0.6 M NaCl. Labeling was achieved by adding 5 μCi each of [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine per ml to the shocked cultures, incubating for 30 min, and then adding an excess of 1 mM l-cysteine hydrochloride and 1 mM l-methionine. The culture tubes were then transferred onto ice. Radiolabeled cells were collected by centrifugation, washed twice in washing buffer (0.1 M Tris HCl [pH 7.5] containing 1 mM EDTA), and finally resuspended in 10 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.5) containing 5 mM MgCl2 and 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. About 0.5 ml of cell suspension was mixed with 0.5 g of 0.17- to 0.18-mm-diameter glass beads (B. Braun Biotech International GmbH, Melsungen, Germany) and homogenized with Shake-it-Baby (Biospec Products, Bartlesville, Okla.). After homogenization for 10 to 20 min, the suspension was centrifuged and the supernatant (CFE) was collected (43).

2D gel electrophoresis.

An excess of chilled methanol was added to CFE containing 50 to 75 μg of protein, and the mixture was kept at −80°C for 1 h before centrifugation (18,000 × g, 5 min, 4°C) to collect the pellet. The pellet was vacuum dried and resuspended in Immobilised pH Gradient (IPG) (Amersham Biosciences) rehydration buffer (8 M urea, 2% [vol/vol] Triton X-100, 0.5% IPG buffer, and a few grains of bromophenol blue). Endonuclease (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) (150 U) was added to the rehydrated sample to remove nucleic acids, and the sample was incubated at room temperature for 20 min. The solution was then added to the IPG strips and rehydrated overnight at 20°C. The rehydrated IPG strips were then placed on a flat electrophoresis unit bed (Amersham Biosciences) and focused at 300 V for 30 min followed by 3,000 V for 4 h. The focused strips were equilibrated (15 min) in equilibration buffer (50 mM Tris HCl [pH 8.8], 6 M urea, 30% [vol/vol] glycerol, 2% [wt/vol] sodium dodecyl sulfate, and a few grains of bromophenol blue) containing either dithioerythritol (1.0%, wt/vol) or iodoacetamide (2.5%, wt/vol). After equilibration, the strips were placed on the top of a vertical homogeneous SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) gel (PROTEAN II xi cell; Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). The electrophoresis was carried out at 20 mA per plate for 15 min followed by 40 mA per plate for 4 h (43).

Western blotting, N-terminal sequencing, and autoradiography.

After 2D electrophoresis was completed, the gels were equilibrated in protein transfer buffer (24.8 mM Tris HCl [pH 8.3], 192 mM glycine, and 10% [vol/vol] methanol) and blotted on a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane by using a Trans-blot apparatus (Bio-Rad) at 24 V overnight at 4°C. Western blotting of membranes with GroEL antibodies was carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions (ECL Western blotting kit; Amersham Biosciences). For N-terminal sequencing, the membrane was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250. The target spots were excised, and N-terminal sequencing was carried out with an amino acid sequencer (model 476A; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). For autoradiography, the polyvinylidene difluoride membrane was exposed to Hyperfilm-βmax (Amersham Biosciences) for up to 2 weeks by using standard procedures. The autoradiograms were scanned with a Fluor-S Multimager System (Bio-Rad). The gels were compared by using the Z3 2D PAGE Analysis System (Compugen Inc, Jamesburg, N.J.) according to the instructions supplied by the manufacturer. The gels were normalized by equating the total volume of all spots in the comparative image to the total volume of all spots in the reference image. The relative absorbance units corresponding to protein spots in different gels were used to determine protein synthesis regulation.

Preparation and analysis of CFEs.

L. rhamnosus HN001 was grown in 2-liter broth cultures and subjected to osmotic shock (0.6 M NaCl) as described above. The control and osmotically shocked cells were harvested (6,500 × g, 10 min, 4°C) and washed with 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.5. The final pellet was resuspended in sterile distilled water (25 ml) and passed through a French press (Spectronic Unicam Instruments, Rochester, N.Y.) at 520 lb/in2. The lysates were centrifuged (29,000 × g, 30 min, 4°C) to separate whole cells and cell wall material from the CFE. The total protein content of the CFE was measured by bicinchoninic acid protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.). Samples of CFEs were added to 70% (vol/vol) cold methanol, stored at −80°C for 14 to 16 h, and then centrifuged (29,000 × g, 20 min, 4°C) to remove the proteins and other alcohol-insoluble material. The supernatant was dried in a Speedvac (Savant Instruments, Holbrook, N.Y.), and the resultant powder was dissolved in water (300 μl). The carbohydrate content was measured by using the phenol-sulfuric acid method (14). The filtered (0.22-μm-pore-size filter) supernatant was analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with a DX500 instrument (Dionex Corp., Sunnyvale, Calif.) with a PA1 column and was monitored by using an ED40 electrochemical detector in pulsed amperometric detection mode. Gradient elution was performed starting at 18 mM NaOH for the first 40 min, followed by a linear gradient to 200 mM NaOH at 55 min, and then with the eluent held at 200 mM NaOH for 5 min. The eluent flow rate was maintained at 1 ml/min. The filtered supernatant was also analyzed by HPLC ion-moderated partition chromatography (1100 series; Hewlett-Packard, Waldbronn, Germany) with an Aminex 42A column (Bio-Rad) (held at 85°C with the guard deashing columns held at 60°C) and elution monitored with a refractive index detector (Hewlett-Packard 1100). Filtered (0.22-μm-pore-size filter) MilliQ water was used as the eluent at 0.4 ml/min. Peaks from the HPLC analysis were collected for mass spectrometry analysis.

Electrospray mass spectrometry analysis.

Underivatized, per-O-methylated, reduced per-O-methylated, and per-O-acetylated carbohydrates were dissolved in water-methanol (1:1, vol/vol) containing 100 μM sodium acetate (10). The oligosaccharides were analyzed in positive-ion mode for all mass spectrometry experiments, using an API 300 triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer with an electrospray source (Perkin-Elmer, Shelton, Conn.).

RESULTS

Growth characteristics of stress-treated cultures of L. rhamnosus HN001.

The growth pattern of L. rhamnosus HN001 after heat shock at 45, 50, and 55°C during the exponential growth phase as monitored by OD610 is shown in Fig. 1. Heat shock at 45°C for 30 min did not influence the growth rate of L. rhamnosus HN001. Heat shock at 50°C retarded the growth rate slightly (20% growth rate depression), and heat shock at 55°C retarded the growth rate severely (100% growth rate depression). At 2 h after heat shock, the OD610 values of the control and 50°C-shocked cultures were 1.25 and 1.0, respectively, whereas the OD610 of the 55°C-shocked culture was only 0.54.

FIG. 1.

Effect of heat shock on the growth of L. rhamnosus HN001 cultures. The cultures were grown in MRS broth at 37°C to an OD610 of 0.4 to 0.5 and subjected to heat shock at 37°C (•), 45°C (○), 50°C (▾), or 55°C (▿) for 30 min. Further growth was monitored at 37°C.

Osmotic shock with 0.3 M NaCl did not affect growth (Fig. 2), but higher salt concentrations (0.4, 0.5, 0.6, and 0.7 M) reduced the growth rate in the range of 12 to 40%. The osmolality of the MRS broth without any salt addition was 390 ± 2 mmol/kg, whereas addition of 0.6 M NaCl raised this value to 1,498 ± 2 mmol/kg.

FIG. 2.

Effect of osmotic shock on the growth of L. rhamnosus HN001 cultures. The cultures were grown in MRS broth at 37°C to an OD610 of 0.7 to 0.8 before being harvested and resuspended in MRS broth containing no NaCl (•) or 0.3 M (○), 0.4 M(▾), 0.5 M (▿), 0.6 M (▪), or 0.7 M (□) NaCl and then further incubated at 37°C.

Storage stability of dried L. rhamnosus HN001 at 30°C.

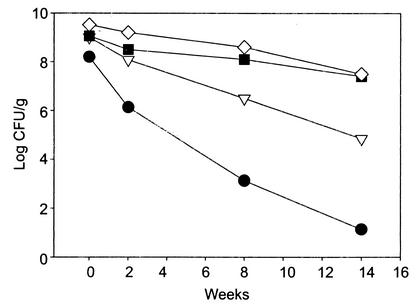

The viability of L. rhamnosus HN001 was monitored by enumerating the viable counts in the dried powder for up to 14 weeks of storage at 30°C (Fig. 3). At the end of 14 weeks, the heat-shocked (stationary-phase) and osmotically shocked cells showed decreases in viability of 1.6 and 2 log units, respectively. The highest viability losses were observed in unstressed control cultures (7.3-log-unit reduction), followed by cultures heat stressed after the mid-log phase (4.16-log-unit reduction).

FIG. 3.

Storage stability of L. rhamnosus HN001 in dried form at 30°C. Cultures were grown in MRS broth, stressed by using either heat or salt, and then harvested and dried as described in Materials and Methods. The powders were stored (30°C) under ambient atmospheric conditions away from sunlight in plastic containers. •, nonstressed; ▿, heat shocked at log phase; ▪, heat shocked at stationary phase; ⋄, osmotically shocked.

Protein synthesis after different growth phases and stress treatments.

The regulation of gene product expression by L. rhamnosus HN001 grown to different growth phases and subjected to different stress treatments was investigated by using 2D PAGE of 35S-labeled proteins and subsequent autoradiography (Fig. 4 to 6). The proteins on the gels were given spot numbers (spots 1 to 46). The N-terminal sequences of 11 proteins were determined and identified by comparison with the available protein sequences in the databases. Matches for the N-terminal sequences of spot 9 could not be found in the protein and nucleotide sequence databases (Table 1). However, the closest match (52% homology) in the L. rhamnosus HN001 genome sequence was found to be tagatose 1,6-diphosphate aldolase.

FIG. 4.

Protein synthesis in an unstressed (control) mid-log-phase L. rhamnosus HN001 culture. An autoradiogram of a 2D PAGE gel of [35S]methionine- and [35S]cysteine-pulse-labeled proteins derived from strain HN001 grown to mid-log phase at 37°C and labeled for 30 min is shown. The proteins were assigned unique spot numbers. GAP, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; TBPA, tagatose 1,6-diphosphate aldolase; PGK, phosphoglycerate kinase; TPI, triose phosphate isomerase.

FIG. 6.

Protein synthesis in an osmotically shocked mid-log-phase L. rhamnosus HN001 culture. An autoradiogram of a 2D-PAGE gel of [35S]methionine- and [35S]cysteine-pulse-labeled proteins of strain HN001 grown to mid-log phase, harvested, resuspended in preheated (37°C) MRS broth (with 0.6 M NaCl), and labeled for 30 min is shown. The proteins on the gel were given unique spot numbers. For abbreviations, see the legend to Fig. 4.

TABLE 1.

Proteins identified by N-terminal sequencing

| Spota | Molecular mass (kDa)b | pIb | N-terminal sequence | Homologous proteinc | Identity (%)d | Organism | Accession no. (SWALLe) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 60 | 4.9 | AKEIKFSEDARA | GroEL | 100 | Lactobacillus zeae | O32847 |

| 6 | 55 | 4.6 | SIITDVLAREVL | Enolase | 90.9 | Streptococcus pneumoniae | Q935W7 |

| 7 | 36 | 4.0 | TVKIGINGFGRI | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 100 | L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus | O32755 |

| 8 | 35 | 5.3 | ASITDKDHQKVI | Lactate dehydrogenase | 100 | L. casei | P00343 |

| 9 | 40 | 5.2 | SVKITAGQLEHLK | Tagatose 1,6-diphosphate aldolase | 52 | L. rhamnosus HN001 genome | |

| 10 | 48 | 5.5 | AKLIVSDLDVKD | Phosphoglycerate kinase | 91.6 | L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus | O32756 |

| 11 | 30 | 5.1 | MRTPFIAGNLK | Triose phosphate isomerase | 81.8 | Clostridium perfringens | BAB81008 |

| 12 | 30 | 4.1 | MRTPFIAGNLK | Triose phosphate isomerase | 81.8 | C. perfringens | BAB81008 |

| 13 | 29 | 5.0 | QLVNAAELVK | Putative ABC transporter protein (membrane-associated ATPase) | 88.9 | C. acetobutylicum | Q97FI2 |

| 28 | 14 | 4.9 | MEKREFNIAAE | Histidine-containing protein (HPr) | 90.9 | L. casei ATCC 393 | Q9KJV3 |

| 33 | 70 | 4.8 | SKVIGIDPGTTN | DnaK | 91.6 | C. pasteurianum | P81341 |

Similarity of the amino acid sequence to a sequence found in the database. The identity of GroEL was confirmed by Western blotting. The similarity searches were done by using the EMBL database with the FASTA3 program. The genes corresponding to all of the proteins were identified in L. rhamnosus HN001.

Based on the number of amino acids matching in the test sequence.

The SWALL database includes Swissport, Trembl, and TrembNew databases.

The protein synthesis levels in unstressed L. rhamnosus HN001 cultures after log-phase growth were compared with the levels after the stationary phase. Also, the protein synthesis patterns in unstressed cultures were compared with those in cultures after heat shock after either the log phase or the stationary phase as well as after osmotic shock after the log phase (Fig. 7). A 10-fold increase in the relative synthesis of the classical heat shock protein GroEL was observed as the L. rhamnosus HN001 culture passed from the log phase to the stationary phase (Fig. 7A). When cultures were subjected to heat shock after log phase, a 15-fold increase in GroEL synthesis was observed. Only a 1.5-fold increase was observed when stationary-phase cultures were subjected to heat shock, whereas osmotically stressed L. rhamnosus HN001 showed a threefold increase (Fig. 7A). For DnaK a similar trend was observed except that the level of DnaK in nonstressed stationary-phase culture was lower than that in nonstressed log-phase culture. The levels of the glycolytic enzymes enolase and lactate dehydrogenase increased by at least twofold when the culture passed from log phase to stationary phase. When heat stress was applied after stationary phase or osmotic stress, the enolase level decreased by about 0.4- and 0.6-fold, respectively. On the other hand, a threefold increase in the lactate dehydrogenase level was observed after osmotic stress. Heat shock at either log or stationary phase did not increase the enzyme levels. A fourfold increase in the level of tagatose-6-phosphate aldolase was observed after either osmotic shock or heat shock after stationary phase. The glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase level marginally increased when heat shock was applied after log phase. Levels of the other enzymes, triose phosphate isomerase and phosphoglycerate kinase, remained relatively unchanged. Heat shock after stationary phase increased the levels of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase and triose phosphate isomerase by 2.5- and 5-fold, respectively. By contrast, the levels of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, phosphoglycerate kinase and triose phosphate isomerase decreased after osmotic stress. The level of ABC transport-related protein was higher in nonshocked stationary-phase culture as well as in cultures after the application of stress treatments compared to nonshocked log-phase culture. The highest increase (twofold) was observed after osmotic stress. The levels of histidine-containing protein HPr were more than threefold higher in cultures after log phase (either without or with heat stress) than in the respective stationary-phase counterparts.

FIG. 7.

Differential regulation of L. rhamnosus HN001 protein synthesis during different stages of growth and stress treatments. After 2D gel electrophoresis and blotting followed by autoradiography, the autoradiograms were scanned by using a Fluor-S Multimager System (Bio-Rad). The gels were compared by using the Z3 2D-PAGE Analysis System (Compugen Inc.). The relative absorbance units (relative protein synthesis) corresponding to protein spots in different gels were used to determine the changes in protein synthesis. (A) Heat shock proteins; (B) glycolysis-related enzymes; (C) other proteins. For each enzyme the bars are as follow, from left to right: nonstressed log-phase cultures, cultures heat shocked after log-phase growth, cultures osmotically stressed after log-phase growth, nonstressed stationary-phase cultures, and cultures heat shocked after stationary phase growth. For abbreviations of the enzymes, see Fig. 4 (GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase).

Carbohydrate metabolites produced during osmotic shock.

In an attempt to verify the accumulation of osmolytes in osmotically stressed L. rhamnosus HN001 cultures, treated and untreated CFEs were analyzed for total sugar and total protein. The sugar/protein ratio was higher in the osmotic shock lysate (20 ± 3 μg/mg of protein) than in the respective control CFE (15 ± 3 μg/mg of protein). Chromatographic analysis of the two CFEs with an Aminex 42A column (data not shown) and a Dionex PA1 column (Fig. 8a) showed significantly different profiles. Comparison of these profiles with those obtained with a malto-oligosaccharide standard and a glycerol standard allowed the identification of tetra-, tri-, di-, and monosaccharide peaks. Further, the electrospray mass spectrometry mass analysis confirmed that these saccharides were both normal and modified tetra-, tri-, di-, and monohexoses (Fig. 8b, methylated oligosaccharides). Figure 8a shows that the monosaccharide levels (peaks 1 and 2) were similar in the control and treated lysates, whereas the disaccharide levels were higher (two- to fourfold) in the osmotically shocked lysate than in the control lysate. Further, the CFE derived from osmotically shocked L. rhamnosus HN001 had relatively more trisaccharides (peaks 7 and 9) and tetrasaccharides (peak 10) than the control lysate. HPLC analysis with the Aminex 42A column (data not shown) showed significantly higher quantities of glycerol in the unstressed (control) culture lysate than in the osmotically stressed culture lysate. Electrospray mass spectrometry analysis was performed for control and osmotically stressed cell lysates on both the unfractionated methanol supernatant and fractions from the Aminex 42A separation. Analysis of the Aminex 42A fractions was done on nonderivatized saccharides, and the whole-lysate methanol supernatant was analyzed in the nonderivatized, per-O-methylated, reduced and then per-O-methylated, and per-O-acetylated forms. The nonderivatized modified mono-, di-, tri-, and tetrasaccharides were observed at m/z 277, 439, 601, and 763 (M + Na) from the fractions and the cell lysate methanol supernatants. These values are 74 atomic mass units (amu) above the m/z observed for unmodified saccharides (containing hexoses), i.e., m/z 203, 365, 527, and 689 (M + Na), respectively. This mass addition could be achieved by a modifying group introducing a further three carbons, two oxygens, and six hydrogens to the saccharides. Comparison between the per-O-methylated samples and those reduced prior to being per-O-methylated showed no difference in mass, suggesting that the modifying group was bound at reducing terminus carbon one. The increase in mass in the per-O-methylated modified saccharides compared to the per-O-methylated nonmodified saccharides is only 88 amu, which indicates that the modifying group must contain two free hydroxyl groups, the first one to compensate for the reducing hydroxyl now involved in the linkage and the second to account for the extra methyl group added to the mass. The 116-amu difference between the per-O-acetylated modified saccharide and that of an equivalent per-O-acetylated nonmodified saccharide also leads to the same conclusion. Hydrolysis of the cell lysate methanol supernatant showed that the oligosaccharides contained the hexoses glucose and galactose. MS-MS experiments on the per-O-methylated modified disaccharide and trisaccharides suggested that the linkages between the hexose residues were 1,4 and 1,6/1,4, respectively, but further linkage analysis is required to confirm this. From the mass spectrometry data obtained to this point, glycerol is the only candidate molecule we have produced that could modify the oligosaccharides and produce the resultant masses, but it is not possible to indicate to which of the three carbons in the glycerol molecule the oligosaccharides are linked.

FIG.8.

(a) Carbohydrate profiles of CFEs derived from control (dashed line) and osmotically stressed (solid line) L. rhamnosus HN001 by using a Dionex PA1 column. The HPLC system used was a Dionex DX500 system with electrochemical detection. The gradient was 18 mM NaOH for 40 min, followed by a linear rise to 200 mM NaOH over 15 min with the elution held at 200 mM for a further 5 min. Peaks 1 and 2, monosaccharides; peaks 3, 4, and 5, disaccharides; peaks 6 through 12, tri- and tetrasaccharides. (b) Electrospray mass spectrometry of methylated control and osmotically stressed L. rhamnosus HN001 CFEs. Normal di-, tri-, and tetrasaccharides have mass/charge ratios (m/z M + Na) of 477, 681, and 885, respectively, when methylated. When the oligosaccharides are modified with glycerol, the methylated m/z values shift to 565, 769, and 973, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Large-scale manufacture of probiotic bacteria involves growth in large-scale fermentors followed by cooling, harvesting, freezing, and/or drying (freeze-drying or convective drying). In the present investigation, we studied the protective effect of prestressing L. rhamnosus HN001 with heat or osmotic shock on the viability of dried preparations during storage. We used fluid bed drying technology to dry the cell concentrate. This process is used extensively in the yeast industry and uses a much lower inlet air temperature than conventional spray drying, and hence it can be used to dry heat-sensitive biological material (37).

Bacteria have evolved stress-sensing systems and defenses against stress, which allow them to withstand harsh conditions and sudden environmental changes (46). The time taken to initiate the stress response is different for different treatments. For example, bacteria respond to heat shock (51) and osmotic shock (20) quickly (in minutes) compared to cold shock (13) (in hours). Among the stress-induced responses studied in bacteria, the heat shock response has been described in greater detail. In Bacillus subtilis, a model organism for gram positive bacteria, the heat shock response is classified into four categories based on the regulators of the genes. Class I genes are regulated by the HrcA repressor, which binds to the palindromic operator sequence CIRCE (for controlled invert repeat of chaperone expression) (52). Class II genes are regulated by sigma factor σB (42). Class III genes are controlled by the class III stress gene repressor CtrR, which binds to a specific direct repeat referred to as the CtsR box (12). The genes regulated by unknown mechanisms are grouped under class IV. For LAB, however, the state of knowledge is quite different. Although heat shock proteins such as DnaK, DnaJ, GrpE, GroES, GroEL, and proteases (Clp, HtrA, FtsH) have been identified and found to be well conserved in LAB, the stress-induced regulatory mechanisms are not well understood (46). In this study, we found the expression of classical heat shock proteins GroEL and DnaK was up-regulated as a result of heat shock as well osmotic shock treatment. Similar observations were recorded for Lactococcus lactis (31, 50, 52). Schmidt et al. (44) investigated the molecular characterization of the dnaK operon in Lactobacillus sakei and reported the regulatory mechanism to be similar to B. subtilis class I stress gene regulation. Stress proteins DnaK and GroEL are known molecular chaperones, i.e., they bind substrate proteins in a transient noncovalent manner, prevent premature folding, and promote the attainment of the correct state in vivo (25). GroEL is also reported to be involved in the protection of mRNA from nuclease degradation, suggesting that it plays an additional role as an RNA chaperone (17). It is speculated that increasing the concentrations of GroEL and DnaK in bacterial cells (by way of stress treatments) prior to their exposure to severe process treatments (such as drying and/or rehydration) offers protection to cellular proteins and other macromolecules from process-induced damage and denaturation (48).

Interestingly, the storage stability of the culture that was heat shocked after stationary phase was superior to that of the culture that was heat shocked after log phase. Classical heat shock proteins (DnaK and GroEL) were found to be up-regulated after both log- and stationary-phase growth, indicating that there are other stationary-phase-related viability factors which can further improve the survival of dried L. rhamnosus HN001. There is evidence to suggest that the onset of stationary phase (33) and starvation conditions (24, 18) confers multiple stress resistance in LAB. It is well established that glucose depletion and starvation conditions prevail in stationary-phase growth cultures. We speculate that these conditions might have conferred multiple stress resistance, leading to the improved storage stability in L. rhamnosus HN001.

Further, in addition to the observed changes in the synthesis of the shock proteins after various growth stages and stress treatments, changes in the synthesis of some glycolytic enzymes were also observed. The glycolytic enzymes identified in this study constitute the glycolytic cycle in the following order: triose phosphate isomerase, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, phosphoglycerate kinase, enolase, and lactate dehydrogenase. At various growth stages and after stress treatments, the levels of the enzymes triose phosphate isomerase, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, and phosphoglycerate kinase were regulated in a similar fashion, indicating that their synthesis is controlled by similar mechanisms. This observation is supported by the genome sequence of L. rhamnosus HN001, which revealed that these genes are clustered into a single operon (M. Lubbers, personal communication). Similar results have been reported for Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus (3). In Lactococcus lactis, the glycolytic enzyme synthesis is also linked to the stress response (31), but unlike in L. rhamnosus HN001, the genes gap and tpi are monocistronic (6, 7). Further, the enzyme tagatose 1,6-diphosphate aldolase (2) was also found to be stress regulated, indicating the utilization of this pathway for energy generation in L. rhamnosus HN001.

Microorganisms respond to a decrease in water activity (increase in osmotic stress) in a medium by accumulating compatible solutes such as glycine betaine and carnitine (28), trehalose (45, 49), glucosyl glycerol (15, 23), and mannosylglycerate (38). These compatible solutes are not inhibitory to cellular processes even at very high concentrations (submolar). With regard to the osmotic stress response in lactobacilli, significant research on Lactobacillus plantarum has been reported. Unlike the enteric bacteria and B. subtilis, in which glycine betaine is synthesized, L. plantarum relies on the uptake of such compounds from the culture medium (20, 28, 29, 30). It is believed that the transport of these compatible solutes occurs through the quaternary ammonium compound transport system (QacT), which belongs to the ABC transport superfamily (20). The accumulation of glycine betaine and carnitine has been shown to enhance survival of L. plantarum after drying (28). These transporter proteins utilize the energy derived from ATP hydrolysis to fuel the transport of solutes across the membrane (27). Our investigation identified an ABC transport-related protein (spot 13) which was found to be up-regulated during osmotic shock, implying solute accumulation.

In order to examine the effect of osmotic shock on carbohydrate metabolism, we investigated changes in levels of sugars during this treatment. The fractionation of carbohydrates in the CFEs by HPLC indicated the presence of mono-, di-, tri-, and tetrasaccharides and glycerol. The lysate derived from osmotically stressed cultures showed lower levels of free glycerol and higher levels of modified oligosaccharides than the control lysate. The mass spectrometry data lead us to believe that the modifying group is glycerol bound to the reducing terminus of the molecule. The glycerol found in control lysates may have been derived from glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate or dihydroxyacetone phosphate via the metabolic pathway described for Leuconostoc oenos (47). The glycerol modification of saccharides will increase the number of hydroxyl groups available in the molecule for interaction with cellular macromolecules (via hydrogen bonding) under conditions of dehydration (water replacement hypothesis [9, 36]), thus leading to protection of these macromolecules and therefore to a better storage stability of L. rhamnosus. Osmotically induced trehalose has been reported to protect E. coli against desiccation damage (49).

In conclusion, our results suggest that the robustness of L. rhamnosus HN001 can be improved by stress adaptation to withstand industrial processes (such as drying and rehydration) and storage conditions. The shock (heat or osmotic) protection acquired by dried L. rhamnosus HN001 may be due to the mechanisms associated with stress proteins along with glycolysis-related machinery and other stationary-phase-related proteins and regulatory factors. The stationary-phase-related factors include osmolyte synthesis and accumulation (26, 40), onset of multiple stress resistance (32), and starvation-induced stress resistance (24, 18). Further understanding on the stress regulatory networks associated with the stationary phase gives us information to control these responses in order to achieve desirable robustness of bacteria in relation to various industrial processes.

FIG. 5.

Protein synthesis in a heat-shocked mid-log-phase L. rhamnosus HN001 culture. An Autoradiogram of a 2D PAGE gel of [35S]methionine- and [35S]cysteine-pulse-labeled proteins derived from strain HN001 grown to mid-log phase at 37°C, shock treated at 50°C, and labeled for 30 min is shown. The proteins on the gel were identified with spot numbers. For abbreviations, see the legend to Fig. 4.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the contribution of Pat Janssen with regard to the fluid bed drying of L. rhamnosus HN001, Julian Reid and Stephanie Harvey for their expertise and useful discussion with regard to protein sequence data and mass spectrometry, Carl Batt (Cornell University, Ithaca, N.Y.) for providing GroEL antibodies, and Tim Coolbear, Ross Holland, and Mark Lubbers for useful discussion and critical reading of the manuscript

REFERENCES

- 1.Ang, D., K. Libereck, D. Skowyra, M. Zylicz, and C. Georgopoulos. 1991. Biological role and regulation of the universally conserved heat shock proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 266:24233-24236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Battenbrock, K., U. Siebers, P. Ehrenreich, and C.-A. Alpert. 1999. Lactobacillus casei 64H contains a phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent phosphotransferase system for uptake of galactose, as confirmed by analysis of ptsH and different gal mutants. J. Bacteriol. 181:225-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Branny, P., F. de la Torre, and J. R. Garel. 1998. An operon encoding three glycolytic enzymes in L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus: glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, phosphoglycerate kinase and triosephosphate isomerase. Microbiology 144:905-914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brassart, D., and E. Schiffirin. 1997. The use of probiotics to reinforce mucosal defence mechanisms. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 8:321-326. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Broadbent, J. R., C. J. Oberg, C. Wang, and L. Wei. 1997. Attributes of heat shock response in three species of dairy Lactobacillus. Sys. Appl. Microbiol. 20:12-19. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cancilla, M. R., A. J. Hillier, and B. E. Davidson. 1995. Lactococcus lactis glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene, gap: further evidence for strongly biased codon usage in glycolytic pathway genes. Microbiology 141:1027-1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cancilla, M. R., B. E. Davidson, A. J. Hillier, N. Y. Nguven, and J. Thomson. 1995. The Lactococcus lactis triosephosphate isomerase gene, tpi, is monocistronic. Microbiology 141:229-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark, D., and J. Parker. 1984. Proteins induced by high osmotic pressure in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 25:81-83. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crowe, J. H., L. M. Crowe, and J. F. Carpenter. 1993. Preserving dry biomaterials: the water replacement hypothesis, part I. BioPharm 6:28-32. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dell, A., A. J. Reason, K.-H. Khoo, M. Panico, R. A. McDowell, and H. R. Morris. 1994. Mass spectrometry of carbohydrate containing biopolymers. Methods Enzymol. 230:108-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeMan, J. C., M. Rogosa, and M. E. Sharpe. 1960. A medium for cultivation of lactobacilli. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 23:130-135. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Derre, I., G. Rapoport, and T. Msadek. 1999. CtsR, a novel regulator of stress and heat shock response, controls clp and molecular chaperone gene expression in gram-positive bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 31:117-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Derzelle, S., B. Hallet, K. Francis, T. Ferain, J. Delcour, and P. Hols. 2000. Changes in cspL, cspP, and cspC mRNA abundance as a function of cold shock and growth phase in Lactobacillus plantarum. J. Bacteriol. 182:5105-5113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dubois, M., K. A. Gilles, J. K. Hamilton, P. A. Rebers, and F. Smith. 1956. Colorimetric method for the determination of sugars and related substances. Anal. Chem. 28:350-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Engelbrecht, F., K. Marin, and M. Hagemann. 1999. Expression of the ggpS gene involved in osmolyte synthesis in the marine cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. strain PCC7002 revealed regulatory differences between this strain and the freshwater strain Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6809. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:4822-4829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Food and Agricultural Organization-World Health Organization. 2001. Report of a joint FAO/WHO expert consultation on evaluation of health and nutritional properties of probiotics in food including powder milk with live lactic acid bacteria, Cordoba, Argentina 1-4 October 2001. [Online.] http://www.fao.org/es/esn/food/foodandfood_probio_en.stm#contacts.

- 17.Georgellis, D., B. Sohlberg, F. U. Hartl, and A. Von Gabain. 1995. Identification of GroEL as a constituent of an mRNA-protein complex in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 16:1259-1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giard, J. C., A. Hartke, S. Flahaut, A. Benachour, P. Boutibonnes, and Y. Auffray. 1996. Starvation-induced multiresistance in Enterococcus faecalis JH2-2. Curr. Microbiol. 32:264-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gill, H. S., K. J. Rutherfurd, J. Prasad, and P. K. Gopal. 2000. Enhancement of natural and acquired immunity by Lactobacillus rhamnosus (HN001), Lactobacillus acidophilus (HN017) and Bifidobacterium lactis (HN019). Br. J. Nutr. 83:167-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glaasker, E., E. H. M. L. Heuberger, W. N. Konings, and B. Poolman. 1998. Mechanism of osmotic activation of the quaternary ammonium compound transporter (QacT) of L. plantarum. J. Bacteriol. 180:5540-5546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gopal, P. K., J. Prasad, J. Smart, and H. S. Gill. 2001. In vitro adherence properties of Lactobacillus rhamnosus DR20 and Bifidobacterium lactis DR10 strains and their antagonistic activity against an enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 67:207-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gouesbet, G., G. Jan, and P. Boyaval. 2002. Two-dimensional electrophoretic study of Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus thermotolerance. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1055-1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hagemann, M., and N. Erdmann. 1994. Activation and pathway of glycosylglycerol synthesis in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Microbiology 140:1427-1431. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hartke, A., S. Bouche, X. Gansel, P. Boutibonnes, and Y. Auffray. 1994. Starvation-induced stress resistance in Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis IL1403. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:3474-3478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hendrick, J. P., and F. U. Hartl. 1993. Molecular chaperone functions of heat-shock proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 62:349-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hengge-Aronis, R., W. Klein, R. Lange, M. Rimmele, and W. Boos. 1991. Trehalose synthesis genes are controlled by the putative sigma factor encoded by rpoS and are involved in stationary-phase thermotolerance in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 173:7918-7924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones, P. M., and A. M. George. 1999. Sub-unit interactions: towards a functional architecture. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 179:187-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kets, E. P. W., and J. A. M. de Bont. 1994. Protective effect of betaine on survival of L. plantarum subjected to drying. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 116:251-256. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kets, E. P. W., E. A Galinski, and J. A. M de Bont. 1994. Carnitine: a novel compatible solute in L. plantarum. Arch. Microbiol. 162:243-248. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kets, E. P. W., P. J. M. Teunissen, and J. A. M. de Bont. 1996. Effect of compatible solutes on survival of lactic acid bacteria subjected to drying. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:259-261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kilstrup, M., S. Jacobsen, K. Hammer, and F. K. Vogensen. 1997. Induction of heat shock proteins DnaK, GroEL, and GroES by salt stress in Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:1826-1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim, W. S., L. Perl, J. H. Park, J. E. Tandianus, and N. W. Dunn. 2001. Assessment of stress response of the probiotic Lactobacillus acidophilus. Curr. Microbiol. 43:346-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim, W. S., J. Ren, and N. W. Dunn. 1999. Differentiation of Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis and subsp. cremoris strains by their adaptive response to stress. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 171:57-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klaenhammer, T., E. Altermann, F. Arigoni, A. Bolotin, F. Breidt, J. Broadbent, R. Cano, S. Chaillou, J. Deutscher, M. Gasson, M. van de Guchte, J. Guzzo, A. Hartke, T. Hawkins, P. Hols, R. Hutkins, M. Kleerebezem, J. Kok, O. Kuipers, M. Lubbers, E. Maguin, L. Mckay, D. Mills, A. Nauta, R. Overbeek, H. Pel, D. Pridmore, M. Saier, D. van Sinderen, A. Sorokin, J. Steele, D. O'Sullivan, W. de Vos, B. Weimer, M. Zagorec, and R. Siezen. 2002. Discovering lactic acid bacteria by genomics. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 82:29-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ko, R., L. T. Smith, and G. M. Smith. 1994. Glycine betaine confers enhanced osmotolerance and cryotolerance on Listeria monocytogenes. J. Bacteriol. 176:426-431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leslie, S. B., E. Israeli, B. Lighthart, J. H. Crowe, and L. M. Crowe. 1995. Trehalose and sucrose protect both membranes and proteins in intact bacteria during drying. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:3592-3597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lievense, L. C., and K. Van't Riet. 1993. Convective drying of bacteria. I. The drying process. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Bio/Technol. 50:45-63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martins, L. O., N. Empadinhas, J. D. Marugg, C. Miguel, C. Ferreira, M. S. da Costa, and H. Santos. 1999. Biosynthesis of mannosylglycerate and genetic characterisation of a mannosylglycerate synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 274:35407-35414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parsell, D. A., and S. Lindquist. 1993. The function of heat-shock proteins in stress tolerance: degradation and re-activation of damaged proteins. Annu. Rev. Genet. 27:437-496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pichereau, V., A. Hartke, and Y. Auffray. 2000. Starvation and osmotic stress induced multiresistances: influence of extracellular compounds. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 55:19-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prasad, J., H. S. Gill, J. Smart, and P. K. Gopal. 1999. Selection and characterisation of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium strains for use as probiotics. Int. Dairy J. 8:993-1002. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Price, C. W., P. Fawcett, H. Ceremonie, N. Su, C. K. Murphy, and P. Youngman. 2001. Genome-wide analysis of the general stress response in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 41:757-774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmid, R., J. Bernhardt, H. Antelmann, A. Volker, H. Mach, U. Volker, and M. Hecker. 1997. Identification of vegetative proteins for a two-dimensional protein index of B. subtilis. Microbiology 143:991-998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schmidt, G., C. Hartel, and W. P. Hammes. 1999. Molecular characterisation of the dnaK operon of Lactobacillus sakei LTH681. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 22:321-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Soto, T., J. Fernandez, J. Vicente-Soler, J. Cansado, and M. Gacto. 1999. Accumulation of trehalose by overexpression of tps1, coding for trehalose-6-phosphate synthase, causes increased resistance to multiple stresses in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:2020-2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van de Guchte, M., P. Serror, C. Chervaux, T. Smokvina, S. D. Ehrlich, and E. Maguin. 2002. Stress response in lactic acid bacteria. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 82:187-216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Veiga-da-Cunha, M., H. Santos, and E. Van Schaftingen. 1993. Pathway and regulation of erythritol formation in Leuconostoc oenos. J. Bacteriol. 175:3941-3948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Walker, D. C., H. S. Girgis, and T. R. Klaenhammer. 1999. The groESL chaperone operon of Lactobacillus johnsonii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:3033-3041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Welsh, D. T., and R. A. Herbert. 1999. Osmotically induced intracellular trehalose, but not glycine betaine accumulation promotes desiccation tolerance in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 174:57-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Whitaker, R. D., and C. A. Batt. 1991. Characterization of heat shock response in Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57:1408-1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yura, T., and K. Nakahigashi. 1999. Regulation of the heat-shock response. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2:153-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zuber, U., and W. Schumann. 1994. CIRCE, a novel heat shock element involved in regulation of heat shock operon dnaK of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 176:1359-1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]