Abstract

Objective: The author studied health information available for veterinary consumers both in print and online.

Methods: WorldCat was searched using a list of fifty-three Library of Congress subject headings relevant to veterinary consumer health to identify print resources for review. Identified items were then collected and assessed for authority, comprehensiveness of coverage, validity, and other criteria outlined by Rees. An in-depth assessment of the information available for feline lower urinary tract disease (FLUTD) and canine congestive heart failure (CHF) was then conducted to examine the availability and quality of information available for specific diseases and disorders. A reading grade level was assigned for each passage using the Flesch-Kincaid formula in the Readability Statistics feature in Microsoft Word.

Results/Discussion: A total of 187 books and 7 Websites were identified and evaluated. More than half of the passages relating to FLUTD and CHF were written above an 11th-grade reading level. A limited quantity of quality, in-depth resources that address specific diseases and disorders and are written at an appropriate reading level for consumers is available.

Conclusion: The library's role is to facilitate access to the limited number of quality consumer health resources that are available to veterinary consumers.

INTRODUCTION AND LITERATURE REVIEW

Pets play a significant role in people's lives, contributing to their physical, psychological, and social well-being. When a pet is injured or ill, family members experience the same feelings of fear, frustration, guilt, worry, confusion, and anxiety they would experience with relatives and other loved ones, sometimes even more. These feelings reflect a natural human tendency for anthropomorphism, defined as the attribution of human-like characteristics or traits to pets or other nonhuman entities [1]. Nearly 70% to 87% of individuals consider their pets full-fledged members of their families [2]. As such, pets are included in wide variety of family activities, from Christmas and birthday celebrations to family vacations, daily exercise, and play. Humans consider a pet to be “a personality in its own right” and thus often describe it as a best friend, sibling, child, or confidante [3].

Nearly 58.3% of US households owned some type of pet in 2001 [4]. Like children, pets depend on their “parents” for a variety of goods and services, including food, grooming, toys, and regular trips to a qualified veterinarian. This means that the veterinary consumer, like any individual responsible for the care of a beloved family member, needs information to make informed health care decisions. While consumer health for humans has been well researched in recent years, veterinary consumer health information remains relatively unexplored. Vreeland attempted to address the issue in a 1999 survey of the policies of academic and veterinary medical school libraries for consumer health reference services. She found no veterinary medical school libraries had a written policy for consumer health reference services [5]. Veterinary consumers, however, are seeking information for their pets. While answering questions for the Urbanhound.com Website, Brevitz learned consumers “wanted clear, complete, understandable information about what was going on with their dogs. In many cases, they already had a diagnosis from their own vets— they just hadn't understood all of the details, and they wanted to know more” [6].

This study examines veterinary consumer health information by assessing the literature that is currently available and evaluating it for authority, comprehensiveness of coverage, significance, validity, ease of use, and overall quality. The paper begins with a description of a typical veterinary consumer to provide context for the reader. An assessment of the current veterinary consumer literature relevant to dogs and cats, the most common companion animals in the United States, follows. The study concludes with an in-depth look at the information available for two companion animal diseases, feline lower urinary tract disease (FLUTD) and canine congestive heart failure (CHF).

THE VETERINARY CONSUMER

While a pet is a highly esteemed member of the family, consumption of health care services for a pet is significantly different than for a regular family member. First, similar to pediatric care, the patient cannot speak for itself. Thus, the veterinary client often must communicate vague symptoms to the veterinarian in an effort to reach a diagnosis and determine an appropriate course of treatment. Second, while health insurance for pets is available, the number of pet owners who carry this insurance remains low [7]. Most veterinary clients pay the entire bill for services rendered, including the price for such high-cost diagnostic procedures as X rays and magnetic resonance images (MRIs). Thus, a family's financial situation is a significant consideration when making decisions regarding a pet's health.

Veterinary clients, however, “are not well informed consumers of veterinary healthcare services” [8]. Like physicians, veterinarians are interested in ensuring optimal health outcomes for their patients. The American Animal Hospital Association recently studied the actions required to improve patient compliance [9]. Defined as client adherence to what veterinarians deem to be the best possible care for their pets, compliance includes following recommendations for preventive care as well as treatment protocols for specific diagnoses. Such compliance requires an informed consumer.

While veterinary practices are encouraged to provide client education materials, they do not have a mandate for this activity. Research on consumer health-information seeking behavior in general, however, indicates consumers seek health care information for a variety of reasons and from a variety of sources, including television, newspapers, the Web, books, print, or email discussion lists. Such activity may encourage a veterinary consumer to initiate a veterinary visit, because a print resource can help an individual determine whether vague symptoms are serious and require further exploration [10]. Further, in the medical community, research has shown that consumer health information facilitates physician-patient communication, an area challenged by medical jargon, physician time constraints, patient anxiety levels, and many other factors [11]. Armed with information, veterinary consumers may be better equipped to frame questions before visits with their veterinarians or know which questions to ask. A challenge for the veterinary consumer, however, is knowing where to access quality information that addresses specific veterinary health issues.

METHODS

A significant number of books related to pets are published in the United States each year. Many are breed specific and follow a rigid template dictated by the series of which they are a part. Such publications often provide basic information regarding general care, health, husbandry, welfare, and training for dogs and cats. Few, however, focus on specific diseases, providing consumers with practical information to assist them in making decisions with their veterinarian.

To identify print publications with information directly related to pet health, WorldCat was searched using a list of fifty-three Library of Congress subject headings that the author identified as relevant to veterinary consumer health (Appendix A). Breed-specific texts following a rigid template format were deleted from search results to reduce the number of publications with nonspecific health information. The search was further limited to the years 1999 to 2004, with a few exceptions if an equivalent resource of known quality could not be located. Online resources were identified using the author's knowledge of current Websites written for consumers by veterinary professional organizations and a list of veterinary consumer health sites compiled by the Pendergrass Agriculture and Veterinary Medicine Library at the University of Tennessee [12].

Resources identified as relevant were then physically assessed for authority, comprehensiveness of coverage, significance, validity, ease of use, and overall quality using the definitions and criteria outlined by Rees [10]. Items the author believed fulfilled these criteria were compiled in a list of “Recommended Resources for the Veterinary Consumer” (Appendix B). To address availability and quality of information on specific diseases and disorders, the indexes, table of contents, and, if online, Websites of all items, regardless of quality, were then searched for information regarding FLUTD or CHF in dogs. These diseases were chosen because the terms describe a broad range of symptoms or signs resulting from various etiologies and pathologies.

While research indicates that most health information for humans is written at the 10th-grade reading level or higher, nearly 50% of Americans read at an 8th-grade or lower level [13]. As a consequence, a common complaint of consumers seeking written health information is that it is either too generic or technical [14]. To examine whether this could also apply to veterinary consumer health information, the passages regarding FLUTD and CHF were evaluated for length and reading grade level. A manual count was conducted to determine the number of words for each passage. Because methods for assessing readability usually produce similar results, a reading grade level was determined using the Readability Statistics feature in the Spelling and Grammar Tools for Microsoft Word [15]. This feature calculates a reading grade level based on the Flesch-Kincaid readability formula. Samples of 300 words were taken from the beginning, middle, and end of each passage and entered into Microsoft Word. The Readability Statistics feature was then run to determine the average number of words per sentence, the average number of syllables per word, a Flesch Reading Ease Score, and a Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level Score. Passages of less than 300 words were not evaluated.

RESULTS

Overall, the author examined 187 books and 7 Websites offering information for veterinary consumers. Of the 187 books, nearly half (89), were authored or coauthored by a doctor of veterinary medicine or foreign equivalent. Only 30 books and 5 Websites were considered to fulfill the criteria provided by Rees and were then placed in the “Recommended Resources for the Veterinary Consumer” (Appendix B). These titles were selected for their relevance to topics of interest to the general public; their comprehensiveness, objectivity, and validity of content; the quality of the author's writing; the text's value for locating additional resources through references or lists of texts for further study; and, most importantly, whether the texts would aid the consumer in making informed decisions regarding their pet's care.

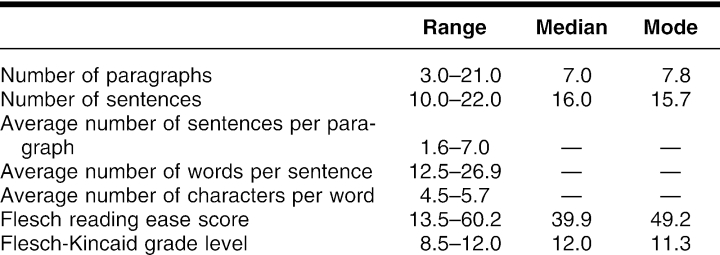

Information regarding FLUTD was located in the indexes and table of contents for 52 of the 185 books and 7 Websites under the index headings, “feline lower urinary tract disease (FLUTD),” “cystitis,” “urolithiasis,” “feline urological syndrome (FUS),” “bladder stones,” “urinary tract infections,” “bladder infections,” and 39 other variations of synonyms and/or terms referring to the symptoms or pathology of this condition. The texts ranged from 102 to 5,489 words in length, with an average passage length of 1,206 words and a median length of 817 words. For each passage, samples of 300 words were taken from the beginning, middle, and end and then evaluated for readability. The results of this evaluation are listed in Table 1. The samples ranged from 10 to 22 sentences in length, with an average of 12.5 to 26.9 words per sentence arranged in 3 to 21 paragraphs. The Flesch-Kincaid score indicated reading levels ranging from the 8th to the 12th grade. More than half of the passages were written at the 12th grade level or higher.

Table 1 Readability of passages concerning feline lower urinary tract disease (FLUTD)

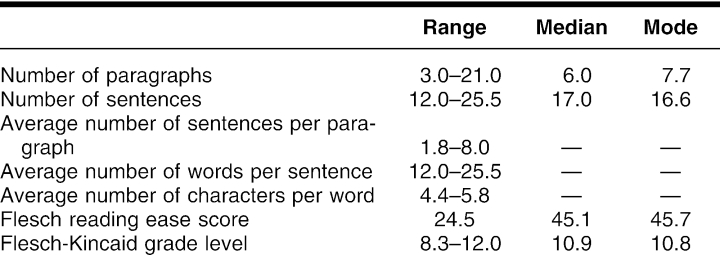

Like FLUTD, information for CHF in dogs was located in the indexes and tables of contents of 47 of the 185 books and 7 Websites using a variety of synonyms and/or terms related to the symptoms or underlying pathology of the disease. Terms included “heart disease,” “cardiomyopathy,” “patent ductus arteriosus,” “heart failure,” “aortic stenosis,” “congestive heart failure,” “heart problems,” “pulmonic stenosis,” “cardiovascular system,” and “congenital heart disease.” Like FLUTD, 72 other index terms were useful for locating information relevant to this condition.

The texts for CHF ranged from 75 to 8,904 words in length, with an average passage length of 1,671 words and a median of 1,015 words. Results for the readability evaluation of the 300-word samples for CHF are listed in Table 2. These samples ranged from 12 to 23 sentences in length, with an average of 12.0 to 25.5 words per sentence arranged in 3 to 21 paragraphs. Reading levels for the CHF samples were slightly lower, with a median reading level of 10th grade and a range of 8th to 12th grade.

Table 2 Readability of passages concerning congestive heart failure (CHF)

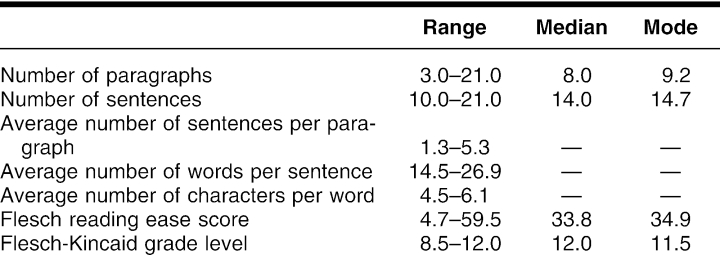

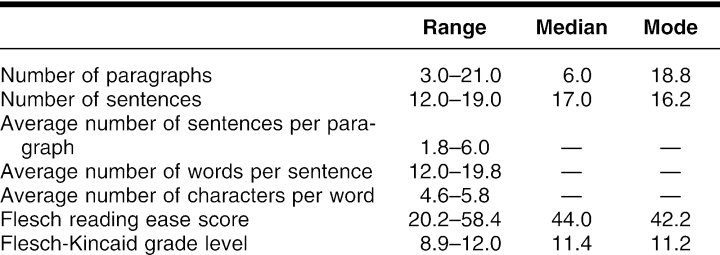

The reading level for texts on the list of “Recommended Resources for the Veterinary Consumer” was also evaluated. Results indicated these texts ranged from the eighth- to twelfth-grade reading level (Tables 3 and 4). Only four print resources on the list contained information regarding FLUTD. Four of the five listed Websites, however, offered twenty-two relevant links with information. More than half of all the FLUTD passages were written above a twelfth-grade reading level. Ten print resources on the list of “Recommended Resources for the Veterinary Consumer” included information on CHF in dogs, while the five Websites offered fourteen relevant links. Of these, more than half were written above an eleventh-grade reading level. The average passage for all resources on the recommended list was written above an eleventh-grade reading level.

Table 3 Readability of passages concerning FLUTD in texts on the “List of Recommended Resources for Veterinary Consumers” (Appendix B)

Table 4 Readability of passages concerning CHF in texts on the “List of Recommended Resources for Veterinary Consumers” (Appendix B)

DISCUSSION

Individuals seeking health information for their pets may be frustrated by a limited amount of quality, in-depth resources addressing specific diseases and disorders that are written at an appropriate reading level. This situation is unfortunate, considering such information could help the owner cope better with anxiety, frustration, or confusion following a pet's diagnosis and ultimately help the owner make decisions about the pet. More than 50% of the entries for FLUTD and CHF in texts meeting the criteria outlined by Rees for relevance, comprehensiveness, objectivity, validity, organization, ease of use, reference value, and consumer orientation were written above an eleventh-grade reading level. These results were similar to a study of consumer health publications recommended for public libraries that found reading levels ranged from tenth to fourteenth grade, higher than the average public's reading level [16]. High reading levels might act as a barrier for individuals seeking veterinary information to aid their decision making.

An additional barrier for veterinary consumers, in general, is a lack of resources that comprehensively cover specific diseases and disorders. Only 52 (27%) of the 185 examined print resources contain information on FLUTD. Only 46 (25%) of these resources offer information on CHF. Of note, all of the Websites on the “Recommended Resources for the Veterinary Consumer” address CHF and all but one address FLUTD. The readability for these Websites, however, varies from 8th to 12th grade, with more than half written above the 12th-grade reading level. Still, while the reading level for these Websites is high, it is noteworthy that consumers would be able to locate information using these resources.

Readability statistics are sometimes criticized for failing to address additional factors that affect an individual's ability to comprehend a text. Such factors include the frequency of technical language, an author's use of passive versus active voice, the cultural appropriateness of the text, the reader's interest, and the appropriateness of the text for the intended audience [16, 17]. Thus, an additional study that examines volunteer's actual comprehension of veterinary consumer health information would be of interest.

Also of interest, MedlinePlus, the US National Library of Medicine's premier consumer health site, offers a Pets and Pet Health page for consumers [18]. However, individuals seeking information on a specific disease or disorder for their pet may be frustrated using this resource, because MedlinePlus is indexed from the human medical perspective. Thus, the Pets and Pet Health page includes many links related to zoonotic diseases, diseases transmissible from animals to humans, in addition to pet health. Further, quality guidelines for MedlinePlus discourage selectors from including sites such as PetPlace.com, Drs. Foster & Smith's PetEducation.com, and the Veterinary Information Network's VeterinaryPartner.com [19–22]. While these Websites all have an educational mission and offer the most comprehensive coverage of diseases and disorders, they are linked to commercial enterprises. PetPlace.com, for example, was founded in 1999 by Rappaport, whose vision was to develop “an unbiased, authoritative, user-friendly website where pet owners worldwide could go for complete, up-to-date information on all pet issues” [23]. While Rappaport chose to pursue his vision by establishing a corporate entity, both Tufts University and the Angell Memorial Hospital of the Massachusetts Society of Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, one of the first humane organizations established in the United States, are respected nonprofit partners in the project. Rappaport's corporation coordinates written contributions from more than eighty veterinarians and seventy-six writers. The articles are available free of charge and do not promote any particular product or service. MedlinePlus, however, currently does not link to PetPlace.com, forcing consumers to learn of the Website from other sources. It is not clear whether MedlinePlus would select this Website after considering the organization's selection guidelines. MedlinePlus only recently added links to Healthypet.com, the consumer Website of the American Animal Hospital Association, to its Pets and Pet Health Web page [24]. Washington State University's Pet Health Topics, a site with a clear educational mission, is also currently not indexed in MedlinePlus [25].

CONCLUSION

The bond between humans and their animal companions may be as deep as the bonds individuals form with friends, siblings, and even spouses. “Pets make us feel good,” note Barton Ross and Baron-Sorenson, both leaders of pet-loss support groups. “they comfort us when we're depressed and share our joy when we're happy. They can be our best friends, our children, physical extensions of ourselves (for disabled people), and someone to share our lives with” [26]. Pet owners feel the same helplessness, fear, and sadness for a pet that is ill, injured, or dying that they would for a close relative. Pets also play an important role in the family, contributing to human welfare by encouraging exercise, facilitating interaction with others, and reducing stress. Research has even shown that having a pet in the family can lower blood pressure and increase survival after a heart attack [27, 28]. With this mutually beneficial relationship, pet owners, or, perhaps more appropriately stated, “caregivers,” have an added incentive to seek quality, comprehensive information to make informed decisions regarding their pets' care. Unfortunately, a limited amount of disease-specific veterinary information, written at an appropriate reading level, is available and accessible to consumers at this time.

The American Animal Hospital Association has noted that negative compliance with veterinary recommendations may be attributed to “the need to impart a large amount of information in a limited amount of time” [9]. Further, the verbal exchange of information between veterinarians and their clients often takes place in a distracting environment, as owners may be receiving recommendations while handling their misbehaving pets or listening over the noise of other animals elsewhere in the veterinary hospital. While a veterinarian may provide written client educational materials, research related to human consumer health has illustrated that consumers seek health information from a variety of sources, not just their physicians. The timing of information is also significantly important. Consumers are sometimes not ready to receive the information offered by a health professional. Anxiety or denial, especially following a shocking diagnosis, can interfere with their ability to absorb and/or process the information exchanged during the clinical consultation. Because one coping mechanism is to seek information from other sources—including friends, family, the Web, books, news articles, and other sources— the library's role is to facilitate access to the limited number of quality resources that are available to veterinary consumers.

APPENDIX A

Library of Congress subject headings used to identify information for veterinary consumers

Alternative veterinary medicine

Animal Diseases—therapy

Cancer in animals

Cat Diseases

Cats

Cats—Aging

Cats—Anatomy

Cats—Breeding

Cats—Diseases

Cats—Encyclopedias

Cats—Food

Cats—Genetics

Cats—Growth & development

Cats—Handbooks, manuals, etc.

Cats—Health

Cats—Injuries

Cats—Nutrition

Cats—Parasites

Cats—Vaccination

Cats—Wounds and injuries

Cats Veterinary medicine

Dog Diseases

Dogs

Dogs—Aging

Dogs—Anatomy

Dogs—Breeding

Dogs—Diseases

Dogs—Encyclopedias

Dogs—Food

Dogs—Genetics

Dogs—Growth & development

Dogs—Handbooks, manuals, etc.

Dogs—Health

Dogs—Injuries—Handbooks

Dogs—Nutrition

Dogs—Parasites

Dogs—Reproduction

Dogs—Surgery

Dogs—Vaccination

Dogs—Wounds and injuries

Dogs Veterinary medicine

First aid for animals

Holistic veterinary medicine

Kittens

Pet loss

Pets—Death

Pets—Diseases

Pets—Feeding and feeds

Pets—Health

Pets—Nutrition

Pets

Puppies

Veterinary medicine

APPENDIX B

List of recommended resources for the veterinary consumer

Ackerman LJ. Canine nutrition: what every owner, breeder, and trainer should know. Loveland, CO: Alpine Publications, 1999.

Ackerman LJ. The genetic connection: a guide to health problems in purebred dogs. Lakewood, CO: AAHA Press, 1999.

American Animal Hospital Association. Healthypet.com. [Web document]. Lakewood, CO: The Association, 2004. [rev.14 Apr 2005; cited 14 Apr 2005]. <http://www.healthypet.com>.

Arden D, Gambardella PC, Brum D. The Angell Memorial Animal Hospital book of wellness and preventive care for dogs. Chicago, IL: Contemporary Books, 2003.

Brackenridge SS. Because of flowers and dancers. Santa Barbara, CA: Veterinary Practice Publishing, 1994.

Brevitz B. Hound health handbook: the definitive guide to keeping your dog happy, healthy & active. New York, NY: Workman, 2004.

Carmack BJ. Grieving the death of a pet. Minneapolis, MN: Augsburg Books, 2003.

Case LP. The cat: its behavior, nutrition, & health. Ames, IA: Iowa State Press, 2003.

Case LP. The dog: its behavior, nutrition, and health. 1st ed. Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press, 1999.

College of Veterinary Medicine, Washington State University. Pet health issues. [Web document]. Pullman, WA: The University, 2004–. [rev. 8 Sep 2005; cited 8 Sep 2005]. <http://www.vetmed.wsu.edu/ClientED/problems_diagnoses.asp>.

Done S. Color atlas of veterinary anatomy: the dog & cat. v.3. London, UK: Mosby-Wolfe, 1996.

Downing R. Pets living with cancer: a pet owner's resource. Lakewood, CO: AAHA Press, 2000.

Duno S. Plump pups and fat cats: a seven-point weight loss program for your overweight pet. 1st ed. New York, NY: St. Martin's Griffin, 1999.

Eldredge D, Bonham MH. Cancer and your pet: the complete guide to the latest research, treatments, and options. Sterling, VA: Capital Books, 2005.

Fogle B. Caring for your dog. 1st US ed. New York, NY: DK Pub, 2002.

Foster R, Smith M. Drs. Foster & Smith PetEducation.com. [Web document]. Rhinelander, WI: Foster & Smith, 1997–. [rev. 27 Jul 2004; cited 27 Jul 2004]. <http://www.peteducation.com>.

Giffin JM, Carlson L. Dog owner's home veterinary handbook. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Howell Book House, 2000.

Gough A, Thomas A. Breed predispositions to disease in dogs and cats. Oxford, UK, and Ames, IA: Blackwell Publishing and Iowa State Press, 2004.

Greene LA, Landis J. Saying good-bye to the pet you love: a complete resource to help you heal. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger, 2002.

Guthrie S, Lane D, Sumner-Smith G. Ultimate dog care: a complete veterinary guide. Lydney, Gloucestershire, UK: Ringpress, 2001.

Hamilton D. Homeopathic care for cats and dogs: Small doses for small animals. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books, 1999.

Intelligent Content. Petplace.com. [Web document]. Weston, FL: Intelligent Content, 1999–.[rev.27 Jul 2004; cited 27 Jul 2004]. <http://www.petplace.com>.

Kaplan L. Help your dog fight cancer: an overview of home care options: featuring Bullet's survival story. Briarcliff, NY: JanGen Press, 2004.

Merck & Co. Merck veterinary manual. [Web document]. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck in cooperation with Merial, 2002–. [rev. 24 Jul 2004; cited 24 Jul 2004]. <http://www.merckvetmanual.com/mvm/>.

Messonnier S. Natural health bible for dogs & cats: your A–Z guide to over 200 conditions, herbs, vitamins, and supplements. 1st ed. Roseville, CA: Prima, 2001.

Nakaya SF. Kindred spirit, kindred care: making health decisions on behalf of our animal companions. Novato, CA: New World Library, 2005.

Neal S. Without regret: a handbook for owners of canine amputees. Sun City, AZ: Doral Publishing, 2002.

Pinney CC. The complete home veterinary guide. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 2004.

Redding RW, Papurt ML. The dog's drugstore: a dog owner's guide to nonprescription drugs and their safe use in veterinary home-care. 1st ed. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press, 2000.

Shojai A. The first-aid companion for dogs & cats. Emmaus, PA: Rodale, 2001.

Sife W. The loss of a pet. Rev. and expanded ed. New York, NY: Howell Book House, 1998.

Stern M, Cropper S. Loving and losing a pet: a psychologist and a veterinarian share their wisdom. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson, 1998.

Straw D. Why is cancer killing our pets?: how you can protect and treat your animal companion. Rochester, VT: Healing Arts Press, 2000.

Tilley LP, Smith FWK. The 5-minute veterinary consult: canine and feline. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004.

Veterinary Information Network. VeterinaryPartner.com. [Web document]. Davis, CA: The Network, 2002–. [rev. 27 Jul 2004; cited 27 Jul 2004]. <http://www.veterinarypartner.com>.

REFERENCES

- Lagoni L, Hetts S, and Butler C. The human-animal bond and grief. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, 1994:10–4. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AM, Katcher AH. Between pets and people: the importance of animal companionship. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press, 1996:41. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschman EC. Consumers and their animal companions. J Consumer Res. 1994 Mar; 20(4):616–32. [Google Scholar]

- American Veterinary Medical Association. U.S. pet ownership & demographics sourcebook. Schaumburg, IL: American Veterinary Medical Association, 2002:6,31,34. [Google Scholar]

- Vreeland CE. A survey of consumer health reference services policies of academic medical school libraries and veterinary medical school libraries. [Web document]. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1999. [rev. 29 Apr 2004; cited 29 Apr 2004]. <http://ils.unc.edu/MSpapers/2515.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- Brevitz B. Hound health handbook: the definitive guide to keeping your dog happy, healthy & active. New York, NY: Workman, 2004:x. [Google Scholar]

- Pet insurance market revenue in U.S. increased 342% over past 5 years, Market Trends reports. Insurance Advocate. 2003 Aug 18; 114(31):50. [Google Scholar]

- Catanzaro TE. Promoting the human-animal bond in veterinary practice. 1st ed. Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- American Animal Hospital Association. The path to high quality care: practical tips for improving compliance. Lakewood, CO: American Animal Hospital Association, 2003:4–25,46. [Google Scholar]

- Rees AM. ed. The consumer health information source book. 5th ed. Phoenix, AZ: Oryx Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Baker L, Manbeck V. Consumer health information for public librarians. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Viera A. Pet health. [Web document]. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee, 2004. [rev. 24 Jul 2004; cited 24 Jul 2004]. <http://www.lib.utk.edu/agvet/veterinary/pethealth.html>. [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch IS. Educational Testing Service, National Center for Education Statistics. Adult literacy in America: a first look at the results of the National Adult Literacy Survey. Washington, DC: Office of Educational Research and Improvement, US Department of Education; Superintendent of Documents, US Government Printing Office, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Dewdney P, Marshall JG, and Tiamiyu MA. A comparison of legal and health information services in public libraries. RQ. 1991 Winter; 31:185–96. [Google Scholar]

- Chall JS. Qualitative assessment of text difficulty: a practical guide for teachers and writers. Cambridge, MA: Brookline Books, 1996:112. [Google Scholar]

- Baker LM, Wilson FL. Consumer health materials recommended for public libraries: too tough to read? Public Libr. 1996 Mar/Apr; 35:124–30. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenbach G, Powell J, Kuss O, and Sa ER. Empirical studies assessing the quality of health information for consumers on the World Wide Web: a systematic review. JAMA. 2002 May 22–29; 287(20):2691–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health. Pets and pet health. [Web document]. Washington, DC: The Library, 2004. [rev. 29 Apr 2004; cited 29 Apr 2004]. <http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/petsandpethealth.html>. [Google Scholar]

- National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health. MedlinePlus quality guidelines. [Web document]. Washington, DC: The Library, 2004. [rev. 18 May 2004; cited 8 Sep 2005]. <http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/criteria.html>. [Google Scholar]

- Intelligent Content. Petplace.com. [Web document]. Weston, FL: Intelligent Content, 1999 –. [rev. 27 Jul 2004; cited 27 Jul 2004]. <http://www.petplace.com>. [Google Scholar]

- Foster R, Smith M. Drs. Foster & Smith PetEducation.com. [Web document]. Rhinelander, WI: Foster & Smith, 1997–. [rev. 27 Jul 2004; cited 27 Jul 2004]. <http://www.peteducation.com>. [Google Scholar]

- Veterinary Information Network. VeterinaryPartner.com. [Web document]. Davis, CA: The Network, 2002 –. [rev. 27 Jul 2004; cited 27 Jul 2004]. <http://www.veterinarypartner.com>. [Google Scholar]

- Intelligent Content. About us. [Web document]. Weston, FL: Intelligent Content, 1999–. [rev. 8 Sep 2005; cited 8 Sep 2005]. <http://www.petplace.com/Corporate/corpSiteTextHandler.asp?code=About+Us>. [Google Scholar]

- American Animal Hospital Association. Healthypet.com. [Web document]. Lakewood, CO: The Association, 2004. [rev. 14 Apr 2005; cited 14 Apr 2005]. <http://www.healthypet.com>. [Google Scholar]

- College of Veterinary Medicine, Washington State University. Pet health topics. [Web document]. Pullman, WA: The University, 2004–. [rev. 8 Sep 2005; cited 8 Sep 2005]. <http://www.vetmed.wsu.edu/ClientED/problems_diagnoses.asp>. [Google Scholar]

- Ross CB, Baron-Sorensen J. Pet loss and human emotion: guiding clients through grief. Washington, DC: Accelerated Development, 1998:15. [Google Scholar]

- Edney AT. Companion animals and human health: an overview. J R Soc Med. 1995 Dec; 88(12):704–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AM, Meyers NM.. Health enhancement and companion animal ownership. Annu Rev Public Health. 1996;17:247–57. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.17.050196.001335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]