Abstract

In this review, we discuss examples that show how glial-cell pathology is increasingly recognized in several neurodegenerative diseases. We also discuss the more provocative idea that some of the disorders that are currently considered to be neurodegenerative diseases might, in fact, be due to primary abnormalities in glia. Although the mechanism of glial pathology (i.e. modulating glutamate excitotoxicity) might be better established for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a role for neuronal–glial interactions in the pathogenesis of most neurodegenerative diseases is plausible. This burgeoning area of neuroscience will receive much attention in the future and it is expected that further understanding of basic neuronal–glial interactions will have a significant impact on the understanding of the fundamental nature of human neurodegenerative disorders.

Keywords: Protein aggregation, tau, α-synuclein, SOD1

Adult onset neurodegenerative diseases represent a major health problem, especially with an aging population. They include disorders as diverse as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), ALS, Huntington’s disease (HD) and the spinocerebellar ataxias. Although the symptoms are divergent, there are two common observations from the pathology of these diseases that indicate some similarities. First, there is a progressive loss of neurons in specific regions of the CNS, which relate approximately to the symptoms that develop. For example, loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra in PD is associated with the movement disorder seen in these patients. Secondly, there are protein aggregates, which are often ubiquitin immunoreactive, in either the cytoplasm or nuclei of the remaining neurons (reviewed by Ciechanover and Brundin, 2003). Many of these disorders also have familial forms in which genetic mutations promote the tendency of these proteins to aggregate (Taylor et al., 2002).

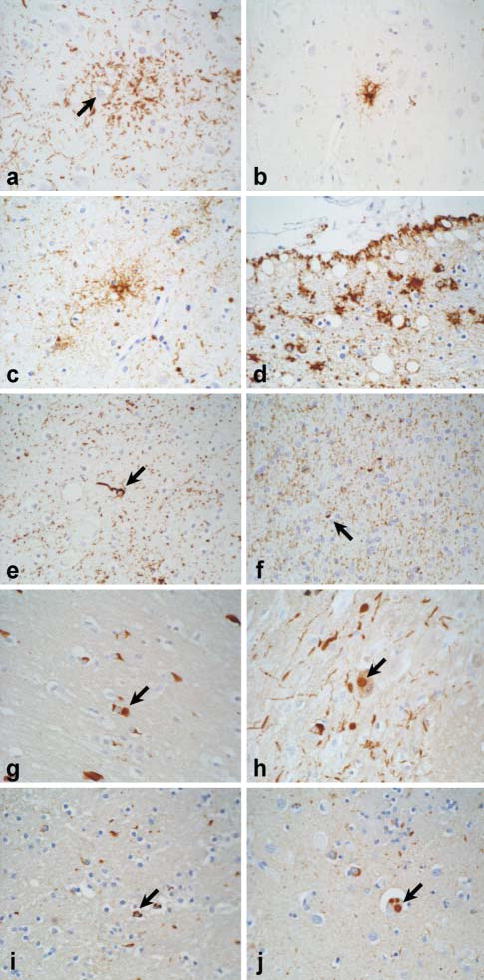

What is perhaps less appreciated is the contribution of glial cells and their interactions with neurons to the neurodegenerative process. Reactive glial changes occur in most, if not all, neurodegenerative diseases. These changes include gliosis in astrocytes (Eng and Ghirnikar, 1994) and activation of microglia (Nelson et al., 2002). There is substantial evidence that such reactive and inflammatory responses make significant contributions to neuronal damage in neurodegenerative diseases. There are excellent reviews of the role of glia in inflammatory responses in AD (McGeer and McGeer, 2002a; Monsonego and Weiner, 2003), PD (Hirsch et al., 2003; Teismann et al., 2003) and ALS (McGeer and McGeer, 2002b). Here, we discuss sporadic and familial neurodegenerative disorders with glial pathology that include inclusion bodies that are composed of protein aggregates analogous to those found in neurons (Chin and Goldman, 1996). First, we describe select examples of glial inclusions in neurodegeneration and highlight the similarities and differences between neuronal and glial inclusions. Some examples of these protein-containing inclusions are demonstrated in Fig. 1. We also discuss recent evidence that non-neuronal cells actively contribute to neuronal loss. This is best illustrated by elegant experiments using transgenic mice that express mutant Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase (SOD1), which is associated with familial ALS. These examples reinforce the idea that glia might not be simple bystanders in the neurodegenerative diseases, but are important contributors to disease pathogenesis.

Fig. 1. Glial lesions in neurodegenerative disorders, demonstrated by immunostaining for either tau or α-synuclein.

(A–F) Staining for tau, (G–J) staining for α-synuclein. (A) In cortico-basal degeneration (CBD), an astrocytic plaque appears as a cluster of short cell-processes around a central unstained astrocyte (arrow). (B) Tufted astrocytes in the motor cortex and basal ganglia are typical of progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP). (C) Tau-positive astrocytes (arrow) are common in the limbic lobe in argyrophilic grain disease (AGD). (D) Thorn-shaped astrocytes are restricted largely to subpial and perivascular regions in the temporal lobe in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. (E) Oligodendroglial coiled bodies (arrow) are common to several of these disorders (e.g. PSP, CBD, AGD and Parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17). (F) Glial-cell pathology is not a prominent feature of typical Pick’s disease, but astrocytic and oligodendroglial lesions (arrow) are detected sometimes, especially in white matter. (G) α-synuclein-positive glial-cell inclusions (GCIs; arrow) are pathognomic of multiple system atrophy (MSA). (H) Neuronal Lewy body-like inclusions (arrow) are also detected often in MSA in the pontine nuclei. Note the presence of neuritic processes, which are similar to those in Lewy body disease. (I) Like MSA, some cases of Lewy body disease, such as those with triplication of the α-synuclein gene locus (Singleton et al., 2003), have GCI-like inclusions (arrow) in affected regions of the basal ganglia and brainstem. (J) The defining lesion of Lewy body disease is the intraneuronal Lewy body [three Lewy bodies in a single neuron (arrow) from the same brain with α-synuclein triplication]. All images are ×400.

Glial cell pathology and intracellular protein inclusions (Table 1)

Table 1.

Glial-cell pathology in inherited and sporadic neurodegenerative diseases

| Diseasea | Areas of pathology | Genes and proteins | Glial-cell pathology | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FTDP-17 | Cerebral cortex, hippocampus, basal ganglia, thalamus, brainstem and cerebellum | MAPT gene, tau protein | Tau inclusions in astrocytes and oligodendrocytes | van Herpen et al., 2003 |

| PSP, CBD and AGD | Motor (PSP), limbic (AGD) and association (CBD) cortices, basal ganglia, thalamus, brainstem and cerebellum | Sporadic, tau protein | Tau inclusions in astrocytes (tufted astrocytes and astrocytic plaques) and oligodendrocytes (coiled bodies) | Chin and Goldman, 1996; Komori, 1999; Dickson, 2004 |

| AD and Aging | Subpial and subependymal regions | Sporadic, tau protein | Tau-positive astrocytes (thorn-shaped astrocytes) | Ikeda et al., 1995; Chin and Goldman, 1996 |

| Familial PD/DLBD | Limbic lobe, basal ganglia and brainstem | SNCA gene, α-synuclein protein | α-synuclein positive inclusions in oligodendrocytes | Gwinn-Hardy et al., 2000 |

| Sporadic PD/DLBD | Limbic lobe, basal ganglia and brainstem | Sporadic, α-synuclein protein | α-synuclein inclusions in oligodendrocytes | Wakabayashi et al., 2000 |

| MSA | Basal ganglia, brainstem and cerebellum | Sporadic, α-synuclein protein | α-synuclein inclusions in oligodendrocytes (GCIs) | Reviewed by Dickson et al., 1999 |

| ALS | Motor cortex and spinal cord | SOD1 gene, SOD1 protein | SOD1 aggregates in astrocytes | Kato et al., 1997; Jonsson et al., 2003 |

Abbreviations: AGD, argyrophilic grain disease; ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; CBD, cortico-basal degeneration; FTDP-17, Parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17; MSA, multiple system atrophy; PD/DLBD, Parkinson’s disease/diffuse Lewy body disease; PSP; SOD1, Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase.

Tauopathies with glial involvement

The microtubule-binding protein tau is recognized as the major protein component of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs). NFTs are intraneuronal proteinaceous inclusions that, along with extracellular amyloid plaques, are a defining pathological hallmark of AD. Mutations in the MAPT gene, which is located on chromosome 17 and encodes the tau protein, are associated with a related disorder, frontotemporal dementia with Parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 (FTDP-17). As its name implies, FTDP-17 has a range of clinical and pathological phenotypes, including cognitive and motor presentations.

The biochemistry of tau has been reviewed in detail elsewhere (Crowther and Goedert, 2000), but a few salient points are germane to this discussion. Six isoforms of tau are generated by alternative mRNA splicing and further micro-heterogeneity is produced by post-translational modifications. Tau is natively disordered in solution, but adopts a higher degree of secondary structure on binding to microtubules. Tau is prone to self-aggregation and aggregated forms of tau form filamentous assemblies that are characteristic of NFTs. The morphology of tau filaments varies depending upon the isoform composition of tau. Finally, tau is a phosphoprotein, and hyperphosphorylation is also associated with aggregation of the protein in NFTs (reviewed by Buee et al., 2000). These properties are similar to another protein that is important in other neurodegenerative disorders, α-synuclein.

Although tau was once thought to be restricted to neurons (Binder et al., 1985), more recent studies indicate that tau is also present in normal glial cells; however, only trace amounts of tau can be detected at basal levels in normal human, bovine and rodent astrocytes (Ksiezak-Reding et al., 2003; Muller et al., 1997; Zientek et al., 1993). Tau is difficult to detect, even in cultured human fetal astrocytes exposed to activating conditions such as interleukin-1β (Liu et al., 1994) and phosphatase inhibitors, including okadaic acid (Ksiezak-Reding et al., 2003). These results indicate that additional factors lead to the production and aggregation of tau protein within astrocytes in neurodegenerative diseases. Alternatively, adult astrocytes have properties that are distinct from fetal astrocytes, which are employed in most cell-culture studies.

Tau is easier to detect in oligodendrocytes, especially in brains that have been subjected to injury or stress, such as ischemia (Irving et al., 1997). It is also readily detected in oligodendrocytes in culture (Ksiezak-Reding et al., 2003; LoPresti et al., 1995; Muller et al., 1997), where it appears to be composed of restricted tau isoforms, similar to the isoform restriction that occurs in neurodegenerative diseases with glial tau inclusions. Specifically, alternative splicing of exon 3 of tau contributes to the heterogeneity in tau isoforms. The function of this domain is not known, but in neurodegenerative diseases that have abundant glial tau-positive inclusions, tau splice forms that lack exon 3 appear to accumulate, based upon lack of immunostaining with exon 3-specific antibodies (Feany et al., 1995; Nishimura et al., 1997). The same is true of oligodendrocytes in culture (Ksiezak-Reding et al., 2003; Richter-Landsberg, 2001).

As mentioned previously, the most widely recognized lesions composed of insoluble, fibrillar aggregates of tau are NFTs in AD, but there are many reports of tau-positive lesions in glia (both astrocytic and oligodendroglial lesions) in other degenerative disorders. The most common disorders with glial tau pathology include PSP, CBD, Pick’s disease and argyrophilic grain disease (AGD) (Dickson, 2004). In each of these, tau-positive inclusions in oligodendrocytes, which are referred to as ‘coiled bodies’, vary in number and distribution between disorders (Fig. 1). Tau-positive astrocytic lesions also occur but are morphologically diverse. They also have more diagnostic significance than coiled bodies in oligodendrocytes. In particular, ‘tufted astrocytes’ of PSP and ‘astrocytic plaques’ of CBD are almost diagnostic of these disorders (Komori et al., 1998). Less distinctive, tau-positive, glial lesions have been described in Pick’s disease and AGD (Fig. 1).

Varying numbers of glial and neuronal tau-positive inclusions occur in morphologically diverse lesions in FTDP-17 (van Herpen et al., 2003). To some extent, the type of glial lesion and their distribution in the brain vary with different MAPT gene mutations, which have different effects on expression and fibrillogenesis of the tau protein (Ghetti et al., 2003). Lesions similar to those found in PSP, CBD and Pick’s disease have all been reported in FTDP-17.

Less frequently, tau-positive glial inclusions are detected in Guam Parkinson-dementia complex (Oyanagi et al., 1997), post-encephalitic Parkinsonism and other neurodegenerative disorders that contain NFTs. Tau-positive astrocytic lesions are found in AD and in the aged human brain in the form of, so-called, ‘thorn-shaped astrocytes’ (Ikeda et al., 1995), but these lesions, which are relatively restricted to the white matter of the medial temporal lobe and the periventricular and subpial regions in the basal forebrain, are not clinically significant and are of no diagnostic importance.

Glial cytoplasmic inclusions (GCI) have come to be recognized as the defining histopathologic hallmark of multiple system atrophy (MSA) (Lantos, 1998) (Fig. 1). These inclusions are found in oligodendroglia, rather than astrocytes, and differ from the inclusions noted previously in their inconsistent immunoreactivity with antibodies to tau epitopes (Cairns et al., 1997), but constant immunoreactivity for ubiquitin and α-synuclein (see later). Finally, astrocytic, tau-positive inclusions have been noted in autosomal recessive juvenile-onset Parkinson’s disease (ARJP) with a parkin gene mutation (van de Warrenburg et al., 2001), although this has not been confirmed in larger autopsy studies of ARJP.

MSA: a sporadic α-synucleinopathy

MSA is a disorder with variable clinical presentations, including Parkinsonism, cerebellar ataxia and autonomic dysfunction (Wenning et al., 1997). Unlike PD, MSA is not responsive to dopamine replacement therapy, which indicates that the Parkinsonism in MSA is due to more widespread degeneration that involves more than the dopaminergic neurons of the pars compacta of the substantia nigra. In fact, it is associated with significant pathology in the basal ganglia. However, the distribution of pathology in the brain is variable and reflects the predominant clinical phenotype, with the major clinical forms (MSA-P and MSA-C) associated with predominant pathology in the nigrostriatal system (MSA-P) and the olivopontocerebellar system (MSA-C).

The unifying histopathologic hallmark of MSA is the GCI, which is a round or crescent-shaped inclusion in the cytoplasm of oligodendroglia in white matter in affected brain regions (Papp et al., 1989). GCIs were detected initially with silver stains (e.g. Gallyas stain) and ubiquitin immunostaining; however, the most sensitive and specific method for detecting GCIs is immunostaining for α-synuclein (Arima et al., 1998; Spillantini et al., 1998; Wakabayashi et al., 1998), which is a small soluble protein that is more abundant in neurons than glia (see later). The GCI is pathognomonic of MSA and a diagnosis of MSA is untenable in the absence of GCIs. It should be noted that many cases of MSA also have neuronal inclusions (both cytoplasmic and nuclear) composed of filamentous α-synuclein, but neuronal lesions are more limited in number and distribution than GCIs. MSA is associated with demyelination and GCIs in white matter tracts, as well as neuronal loss in the basal ganglia, substantia nigra, pontine nuclei, inferior olive and cerebellum. Given the presence of α-synuclein in GCIs it is reasonable to assume that α-synuclein and oligodendroglial dysfunction play central roles in the pathogenesis of MSA. However, it is still a mystery whether neuronal or glial deficits are primary to the disease process.

Several lines of evidence indicate that α-synuclein is a predominantly neuronal protein in the normal, adult CNS. Several immunostaining studies, including the early work of Maroteoux and others, have shown that α-synuclein localizes to the presynaptic terminals of neurons (Maroteaux et al., 1988). The cognate mRNA is expressed in gray matter, but not in white matter, of normal, human brain (Solano et al., 2000). Moreover, α-synuclein immunostaining in white matter tracts in human brain is generally attributed to neuronal α-synuclein protein (Irizarry et al., 1996; Iwai et al., 1995), although one report suggests weaker glial expression that is enhanced in proteinase K-treated sections (Mori et al., 2002).

Given that α-synuclein usually has limited expression in glial cells, how might it occur there in MSA? The most parsimonious explanation is that oligodendroglia express α-synuclein at low levels normally but that expression increases because of some abnormal stress in the disease. Transient expression of α-synuclein has been demonstrated in rat oligodendrocytes as they mature in culture (Richter-Landsberg et al., 2000), and there is a report of the detection of low levels of α-synuclein in glia in vivo (Mori et al., 2002). α-synuclein mRNA and protein is also found in astroglioma cells in vitro, where it can be upregulated by the inflammatory cytokine interleukin-1β and serum deprivation (Tanji et al., 2001). It is not known whether these stressors can increase α-synuclein expression in mature, non-transformed oligodendrocytes. More provocatively, one might hypothesize that apparent increased concentrations of protein are caused by post-translation stabilization or lack of turnover of α-synuclein in diseased glia. In support of this idea, tau can be induced to form inclusions in oligodendrocytes in culture, if the proteasome is inhibited and tau turnover is slowed (Goldbaum et al., 2003).

An alternative, if less likely, possibility is that oligodendrocytes take up α-synuclein released from neurons. It has been shown that α-synuclein is present in cerebrospinal fluid (Borghi et al., 2000) and plasma from human patients and in culture media from neuronal cell lines (El-Agnaf et al., 2003). This demonstrates that some of the α-synuclein protein synthesized within cells is translocated to the extracellular space. However, these observations do not identify whether this is a regulated phenomenon or whether it results from membrane lysis in a small number of neurons. The observation that some α-synuclein might be glycosylated (Shimura et al., 2001) indirectly supports the idea that secretion is active and regulated, as many proteins that undergo regulated secretion are glycosylated whilst passing through the ER and golgi. However, the molecular weight of α-synuclein from extracellular sources does not indicate any post-translational modification (Borghi et al., 2000; El-Agnaf et al., 2003). Once in the extracellular fluid, oligodendroglia would have to take up α-synuclein. Some cell lines can endocytose α-synuclein from media via a rab5-dependent pathway (Sung et al., 2001). Whether mature oligodendrocytes in vivo have such capacity is unknown. Therefore, the hypothesis that α-synuclein is exported from neurons and acquired by glia is conjectural at present.

Some of these issues could be resolved by looking in detail at α-synuclein from GCIs. Recently, an ultrastructural study of GCIs revealed that full-length α-synuclein is present in GCIs (Gai et al., 2003), which indicates that there is no requirement for protein truncation and post-translational modification before the protein accumulates in GCIs. Fibrils of α-synuclein in GCIs are in parallel bundles rather than the radiating pattern of α-synuclein fibrils in Lewy bodies, the predominant neuronal lesion found in PD and related disorders. This indicates that different fibrillization mechanisms might be involved in MSA compared to other α-synucleinopathies.

Hyperphosphorylation of α-synuclein has been suggested to be a key event in the formation of GCIs. Hyperactivity of casein kinases (Fujiwara et al., 2002; Okochi et al., 2000) and G-protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRKs) (Pronin et al., 2000) has been implicated, because these enzymes have been shown to phosphorylate α-synuclein. Phosphorylation via GRKs interferes with the inhibitory effects of α-synuclein on phospholipase D2 (PLD2), which is important for phosphorylation of cytoskeletal proteins. Increased PLD2 activity can cause rearrangement of actin cytoskeleton (Pronin et al., 2000). Interestingly, GCIs are immunoreactive for cyclin-dependent kinase (Nakamura et al., 1998) and its activator, p39 (Honjyo v 2001) indicating that upregulation of these proteins in oligodendroglia might be a mediating factor in increased cytoskeletal phosphorylation and subsequent GCI formation.

In light of the differences between α-synuclein in glial and neuronal inclusions, it is important to note that lesions can be found in both types of cells in some cases. In addition to MSA, α-synuclein-immunoreactive oligodendroglial inclusions are recognized increasingly in PD (Wakabayashi et al., 2000). Likewise, α-synuclein-positive neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions can be present in MSA (Yokoyama et al., 2001). These observations imply that there might be common mechanisms in neurons and glia that promote the formation of α-synuclein inclusions. One route to α-synuclein pathology in neurons and oligodendrocytes might be through a net increase in concentration of α-synuclein protein. The recent discovery that triplication of the α-synuclein gene results in a net doubling of the α-synuclein protein concentration in affected members of the ‘Iowa kindred’ provides direct support for this idea (Singleton et al., 2003). Interestingly, in addition to Lewy body pathology, GCI-like pathology has been demonstrated in these cases (Gwinn-Hardy et al., 2000) (Fig. 1). This provides further support for neuronal–glial interplay in the pathogenesis of MSA and also indicates that the mechanisms involved in the formation of neuronal and glial α-synuclein lesions might not be completely distinct.

Active contribution of glia to neurodegeneration

The presence of tau-positive and α-synuclein-positive glial inclusions indicates that astrocytes and oligodendrocytes play a role in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases. However, these observations do not easily answer a second, crucial question: Is this role primary or secondary? Clearly, reactive glial changes (e.g. microglia and astrocytes) are involved in all brain disorders in response to neuronal injury or loss, and they might play a more active or even a primary role in autoimmune and demyelinating diseases.

For reasons of brevity, the present discussion is limited to neurodegenerative diseases, where the contribution of glia to pathogenesis is less clearly defined. Although the role of glia in developmental and demyelinating disorders is not discussed, it is worth noting that mutations in the gene that encodes the astrocytic intermediate filament protein, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), cause Alexander’s disease. This is an inherited leukodystrophy that is associated with marked loss of myelin and the presence of inclusion bodies, composed of the small heat-shock protein, αΒ -crystallin, in astrocytes (Messing and Brenner, 2003). This disorder provides insights into the roles of abnormalities in structural proteins of astrocytes on myelin integrity and of heat shock proteins on inclusion-body formation. Moreover, neuronal loss in this disorder is either directly or indirectly attributable to mutations in a gene whose expression is restricted to astrocytes, which further emphasizes that, currently, we might underestimate the roles of glia in neurodegeneration.

Glial pathology in familial ALS

An example of the active role that glia can play in a neurodegenerative disease is given by familial ALS (FALS). Mutations in SOD1 are associated with autosomal dominant FALS, and a large number of mutations are scattered throughout this small but abundant cytoplasmic protein (see http://alsod.org). Since the initial discovery of mutations in this gene (Rosen et al., 1993), several theories have been proposed for the dramatic loss of motor neurons in the cerebral cortex, brainstem and spinal cord (reviewed by Cleveland and Rothstein, 2001). The pathology of FALS is characterized by the presence of intraneuronal inclusion bodies, which are composed of SOD1 (Rowland and Shneider, 2001). This has led to the suggestion that protein aggregation might be a facet of this disease, as it is in several other degenerative disorders (Ciechanover and Brundin, 2003; Taylor et al., 2002). The current predominant theory is that misfolding of mutant SOD1 contributes to neurotoxicity of motor neurons in FALS (Valentine and Hart, 2003). A recent example of this is the observation that an out of frame mutation (G127insTGGG) causes ALS with aggregate formation, even at low levels of expression of mutant SOD1 (Jonsson et al., 2003). Hyaline inclusions, which are similar to Lewy bodies, have been described recently in astrocytes in some families with FALS (Kato et al., 1997; Kato et al., 2000) and in transgenic animals bearing FALS mutations (Bruijn et al., 1997; Bruijn et al., 1998). Inclusions have been noted in oligodendroglia in one transgenic model (Stieber et al., 2000). Interestingly, inclusions can be present in both neurons and astrocytes in affected areas in humans (Jonsson et al., 2003) and transgenic mice (Bruijn et al., 1998), but whether this is causal or correlative cannot be distinguished. The time-course of formation of neuronal and glial inclusions has been reported in G93A-SOD1 transgenic mice (Stieber et al., 2000).

Experiments in vivo strongly support the idea that astrocytes play more than a correlative role in FALS. Expression of many variants of mutant human SOD1 in transgenic mice produces substantial loss of motor neurons in the spinal cord, clinically evident motor deficits and, eventually, death. One of the first examples was the generation of G93A mutant mice under control of the human SOD1 promoter (Gurney et al., 1994). Although G93A-SOD1 is expressed in most cell types of the body, it produces selective loss of motor neurons. Subsequent experiments using restricted promoters have shown that expression in either neurons or glial cells alone is insufficient to trigger toxicity. Expressing G37R-SOD1 using the low molecular weight neurofilament protein promoter, which expresses in most neuronal types (Pramatarova et al., 2001) does not cause disease, unlike previous reports using the same mutation (Wong et al., 1995) but less restrictive promoters. Similarly, expression of G86R-SOD1 in astrocytes using the GFAP promoter does not result in loss of motor neurons (Gong et al., 2000). Hence, expression of mutant SOD1 in non-neuronal cells is required, but not sufficient to induce motor neuron death.

The interpretation of some of these results might be clouded slightly by the use of different mouse strains in different experiments and the uncertainty of whether the absolute level of expression of the mutant proteins is equivalent with the different restrictive promoters. Some of these questions have been addressed more directly by Clement et al. in elegant experiments using chimeric mice (Clement et al., 2003). By injecting wild-type embryonic stem (ES) cells into blastocysts from mice that express one of two mutant SOD1 genes, chimeric animals with different numbers of cells expressing mutant SOD1 were created. The animals with fewer cells that expressed mutant SOD1 survived longer than those in which more cells expressed the mutant SOD1 transgene. The same group repeated these experiments using another technique; aggregation of morulae from wild-type and mutant mice. In this experiment, cellular identity (neurons versus glia) is beginning to be established in each of the morulae that are aggregated together, which leads to chimeras with different numbers of neuronal and non-neuronal cells that express mutant SOD1. Crucially, motor neurons expressing mutant SOD1 survived in some of these chimeric animals. If mutant-SOD1-mediated toxicity is purely a cell-autonomous event, then one would predict that all the neurons that express mutant SOD1 would be affected, but this was not the case. Furthermore, in some chimeras all the motor neurons were mutant, whereas non-neuronal cells were a mixture of mutant and wild type. In these animals, motor-neuron survival correlated with the proportion of non-neuronal cells that were wild type; thus expression of mutant SOD1 in non-neuronal cells provides a detrimental environment and promotes the damaging effects of mutant SOD1 in motor neurons.

What is the mechanism involved and what are the molecular targets of mutant SOD1 in non-neuronal cells? A large proportion of non-neuronal cells in the ventral horn of the spinal cord are astrocytes, which play key roles in maintaining a homeostatic environment. Shortly after the discovery of SOD1 mutations, Rothstein and colleagues reported a loss of glutamate transporter protein (either GLT1 or EAAT2) in glia from the spinal cord and cortex of patients with sporadic ALS (Rothstein et al., 1995). This provides one of several lines of evidence that indicate a possible role of glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity in this disease (Shaw and Eggett, 2000). Subsequently, some studies show a loss of glutamate transport in astrocytes from transgenic animals expressing mutant SOD1 (Howland et al., 2002). Mutant SOD1 reduces the activity of EAAT2 when co-expressed in oocytes (Trotti et al., 1999), indicating a direct effect. Therefore, a reasonable target for mutant SOD1 in non-neuronal cells is astrocytic transport of glutamate from the synaptic cleft. It should be emphasized that the primary evidence for altered EAAT2 expression comes from sporadic, not FALS (Rothstein et al., 1995). This might mean that failure of astrocyte-mediated glutamate transport is common to both forms of the disease and implies a central role of glial cells in neurodegeneration (Trotti et al., 1998).

Whether aggregated SOD1 is important in mediating loss of EAAT2 function in FALS or whether the mutant proteins have a more direct action is unclear. However, it is interesting that blocking glutamate-mediated Ca2+ entry through a subclass of AMPA receptors decreases both protein aggregation and cell death of motor neurons in vitro (Roy et al., 1998). Therefore, it is possible that stressors in the microenvironment surrounding motor neurons potentiate protein aggregation and cell death, and that damage to glia hampers their ability to prevent this stress-mediated effect. Whether similar mechanisms apply in other diseases is not yet clear, but the presence of inclusions in glial cells in several neurodegenerative conditions suggests that this is worth examining further.

Other models that include glial pathology

Are the observations of a contribution of glia to mutant SOD1 toxicity limited to ALS models, or are they more general phenomena in neurodegenerative diseases? Transgenic models expressing human tau sometimes have glial cell inclusions in addition to neuronal inclusions (Gotz et al., 2001; Lin et al., 2003) and, in one case, in the absence of obvious neuronal inclusions (Higuchi et al., 2002). Most of these animals (including those with glial but not neuronal lesions) develop motor problems (Higuchi et al., 2002). Thus, it is tempting to speculate that aggregation of tau in glial cells contributes to neuronal damage in a way that is similar to aggregation of SOD1 in glia. However, experiments to address whether expression of tau in glia alone, such as restricting to one cell type, is sufficient to trigger degeneration in surrounding neurons have not yet been performed.

The relatively restricted glial pathology in MSA might be indicative of similar glial-driven neuronal damage. This has been addressed, in part, using transgenic mice that overexpress α-synuclein. Overexpression of α-synuclein from a neuronal promoter does not result in GCI-like pathology (reviewed by Hashimoto et al., 2003). However, when α-synuclein is overexpressed exclusively in oligodendroglia via a proteolipid protein (PLP) promoter, GCI-like inclusions form in these cells (Kahle et al., 2002). Although PLP-α-synuclein mice do not have a behavioral phenotype, the inclusions resemble human GCIs. Moreover, α-synuclein is hyperphosphorylated at residue S129 in this mouse model, a modification that is found in human α-synucleinopathies. The accumulation of phosphorylated α-synuclein might be an early event in the pathology of MSA because this post-translational modification is known to enhance α-synuclein fibrillization (Fujiwara et al., 2002). As these PLP-α-synuclein mice demonstrate neither a behavioral phenotype nor argyrophilic inclusions, it is speculated that the α-synuclein-containing inclusions represent an early phase of GCI formation. Thus, ectopic expression of α-synuclein in oligodendroglia does not seem to be sufficient for the complete pathogenesis of MSA, but it might mimic early stages of cellular pathology. These experiments do not address directly the question of whether α-synuclein is expressed by oligodendrocytes in MSA or whether it is produced in neurons and exported to glia, as discussed previously.

Overall, these model systems only partly address whether glial pathology is a significant contributor to neuronal damage. However, it is tempting to speculate that glia make active contributions to neuronal cell death in diseases other than ALS, and experiments designed to address this hypothesis are eagerly awaited.

References

- Arima K, Ueda K, Sunohara N, Arakawa K, Hirai S, Nakamura M, et al. NACP/alpha-synuclein immunoreactivity in fibrillary components of neuronal and oligodendroglial cytoplasmic inclusions in the pontine nuclei in multiple system atrophy. Acta Neuropathologica. 1998;96:439–444. doi: 10.1007/s004010050917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder LI, Frankfurter A, Rebhun LI. The distribution of tau in the mammalian central nervous system. Journal of Cell Biology. 1985;101:1371–1378. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.4.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borghi R, Marchese R, Negro A, Marinelli L, Forloni G, Zaccheo D, et al. Full length alpha-synuclein is present in cerebrospinal fluid from Parkinson’s disease and normal subjects. Neuroscience Letters. 2000;287:65–67. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01153-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruijn LI, Becher MW, Lee MK, Anderson KL, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, et al. ALS-linked SOD1 mutant G85R mediates damage to astrocytes and promotes rapidly progressive disease with SOD1-containing inclusions. Neuron. 1997;18:327–338. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80272-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruijn LI, Houseweart MK, Kato S, Anderson KL, Anderson SD, Ohama E, et al. Aggregation and motor neuron toxicity of an ALS-linked SOD1 mutant independent from wild-type SOD1. Science. 1998;281:1851–1854. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5384.1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buee L, Bussiere T, Buee-Scherrer V, Delacourte A, Hof PR. Tau protein isoforms, phosphorylation and role in neurodegenerative disorders. Brain Research Reviews. 2000;33:95–130. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(00)00019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns NJ, Atkinson PF, Hanger DP, Anderton BH, Daniel SE, Lantos PL. Tau protein in the glial cytoplasmic inclusions of multiple system atrophy can be distinguished from abnormal tau in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience Letters. 1997;230:49–52. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00474-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin SS, Goldman JE. Glial inclusions in CNS degenerative diseases. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 1996;55:499–508. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199605000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciechanover A, Brundin P. The ubiquitin proteasome system in neurodegenerative diseases. Sometimes the chicken, sometimes the egg. Neuron. 2003;40:427–446. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00606-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement AM, Nguyen MD, Roberts EA, Garcia ML, Boillee S, Rule M, et al. Wild-type nonneuronal cells extend survival of SOD1 mutant motor neurons in ALS mice. Science. 2003;302:113–117. doi: 10.1126/science.1086071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland DW, Rothstein JD. From Charcot to Lou Gehrig: deciphering selective motor neuron death in ALS. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2001;2:806–819. doi: 10.1038/35097565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowther RA, Goedert M. Abnormal tau-containing filaments in neurodegenerative diseases. Journal of Structural Biology. 2000;130:271–279. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2000.4270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson D.W. (2004) Sporadic tauopathies: Pick’s disease, corticobasal degeneration, progressive supranuclear palsy and argyrophilic grain disease. In Esiri, M., Lee, V.M.-Y. and Trojanowski, J.Q. (eds) Neuropathology of Dementia, Second Edition Cambridge University Press, pp. 227–256.

- Dickson DW, Lin W, Liu WK, Yen SH. Multiple system atrophy: a sporadic synucleinopathy. Brain Pathology. 1999;9:721–732. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1999.tb00553.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Agnaf OM, Salem SA, Paleologou KE, Cooper LJ, Fullwood NJ, Gibson MJ, et al. Alpha-synuclein implicated in Parkinson’s disease is present in extracellular biological fluids, including human plasma. FASEB Journal. 2003;17:1945–1947. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0098fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eng LF, Ghirnikar RS. GFAP and astrogliosis. Brain Pathology. 1994;4:229–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1994.tb00838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feany MB, Ksiezak-Reding H, Liu WK, Vincent I, Yen SH, Dickson DW. Epitope expression and hyperphosphorylation of tau protein in corticobasal degeneration: differentiation from progressive supranuclear palsy. Acta Neuropathologica. 1995;90:37–43. doi: 10.1007/BF00294457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara H, Hasegawa M, Dohmae N, Kawashima A, Masliah E, Goldberg MS, et al. alpha-synuclein is phosphorylated in synucleinopathy lesions. Nature Cell Biology. 2002;4:160–164. doi: 10.1038/ncb748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gai WP, Pountney DL, Power JH, Li QX, Culvenor JG, McLean CA, et al. alpha-synuclein fibrils constitute the central core of oligodendroglial inclusion filaments in multiple system atrophy. Experimental Neurology. 2003;181:68–78. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(03)00004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghetti B., Hutton M.L. and Wszolek Z.K. (2003) Frontotemporal dementia and Parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 associated with Tau gene mutations (FTDP-17T). In DW, D. (ed) Neurodegeneration: The Molecular Pathology of Dementia and Movement Disorders. ISN Neuropath Press, pp. 86–102.

- Goldbaum O, Oppermann M, Handschuh M, Dabir D, Zhang B, Forman MS, et al. Proteasome inhibition stabilizes tau inclusions in oligodendroglial cells that occur after treatment with okadaic acid. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23:8872–8880. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-26-08872.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong YH, Parsadanian AS, Andreeva A, Snider WD, Elliott JL. Restricted expression of G86R Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase in astrocytes results in astrocytosis but does not cause motoneuron degeneration. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20:660–665. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-02-00660.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotz J, Tolnay M, Barmettler R, Chen F, Probst A, Nitsch RM. Oligodendroglial tau filament formation in transgenic mice expressing G272V tau. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;13:2131–2140. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurney ME, Pu H, Chiu AY, Dal Canto MC, Polchow CY, Alexander DD, et al. Motor neuron degeneration in mice that express a human Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase mutation. Science. 1994;264:1772–1775. doi: 10.1126/science.8209258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwinn-Hardy K, Mehta ND, Farrer M, Maraganore D, Muenter M, Yen SH, et al. Distinctive neuropathology revealed by alpha-synuclein antibodies in hereditary Parkinsonism and dementia linked to chromosome 4p. Acta Neuropathologica. 2000;99:663–672. doi: 10.1007/s004010051177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto M, Rockenstein E, Masliah E. Transgenic models of alpha-synuclein pathology: past, present, and future. Annals of the NY Academy of Sciences. 2003;991:171–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi M, Ishihara T, Zhang B, Hong M, Andreadis A, Trojanowski J, et al. Transgenic mouse model of tauopathies with glial pathology and nervous system degeneration. Neuron. 2002;35:433–446. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00789-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch EC, Breidert T, Rousselet E, Hunot S, Hartmann A, Michel PP. The role of glial reaction and inflammation in Parkinson’s disease. Annals of the NY Academy of Sciences. 2003;991:214–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honjyo Y, Kawamoto Y, Nakamura S, Nakano S, Akiguchi I. P39 immunoreactivity in glial cytoplasmic inclusions in brains with multiple system atrophy. Acta Neuropathologica. 2001;101:190–194. doi: 10.1007/s004010000246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howland DS, Liu J, She Y, Goad B, Maragakis NJ, Kim B, et al. Focal loss of the glutamate transporter EAAT2 in a transgenic rat model of SOD1 mutant-mediated amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2002;99:1604–1609. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032539299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda K, Akiyama H, Kondo H, Haga C, Tanno E, Tokuda T, et al. Thorn-shaped astrocytes: possibly secondarily induced tau-positive glial fibrillary tangles. Acta Neuropathologica. 1995;90:620–625. doi: 10.1007/BF00318575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irizarry MC, Kim TW, McNamara M, Tanzi RE, George JM, Clayton DF, et al. Characterization of the precursor protein of the non-A beta component of senile plaques (NACP) in the human central nervous system. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 1996;55:889–895. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199608000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irving EA, Yatsushiro K, McCulloch J, Dewar D. Rapid alteration of tau in oligodendrocytes after focal ischemic injury in the rat: involvement of free radicals. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 1997;17:612–622. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199706000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwai A, Yoshimoto M, Masliah E, Saitoh T. Non-A beta component of Alzheimer’s disease amyloid (NAC) is amyloidogenic. Biochemistry. 1995;34:10139–10145. doi: 10.1021/bi00032a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson PA, Ernhill K, Andersen PM, Bergemalm D, Brannstrom T, Gredal O, et al. Minute quantities of misfolded mutant superoxide dismutase-1 cause amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain. 2004;127:73–88. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahle PJ, Neumann M, Ozmen L, Muller V, Jacobsen H, Spooren W, et al. Hyperphosphorylation and insolubility of alpha-synuclein in transgenic mouse oligodendrocytes. EMBO Reports. 2002;3:583–588. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato S, Hayashi H, Nakashima K, Nanba E, Kato M, Hirano A, et al. Pathological characterization of astrocytic hyaline inclusions in familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. American Journal of Pathology. 1997;151:611–620. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato S, Takikawa M, Nakashima K, Hirano A, Cleveland DW, Kusaka H, et al. New consensus research on neuropathological aspects of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) gene mutations: inclusions containing SOD1 in neurons and astrocytes. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Other Motor Neuron Disorders. 2000;1:163–184. doi: 10.1080/14660820050515160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komori T. Tau-positive glial inclusions in progressive supra-nuclear palsy, corticobasal degeneration and Pick’s disease. Brain Pathology. 1999;9:663–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1999.tb00549.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komori T, Arai N, Oda M, Nakayama H, Mori H, Yagishita S, et al. Astrocytic plaques and tufts of abnormal fibers do not coexist in corticobasal degeneration and progressive supranuclear palsy. Acta Neuropathologica. 1998;96:401–408. doi: 10.1007/s004010050911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ksiezak-Reding H, Farooq M, Yang LS, Dickson DW, LoPresti P. Tau protein expression in adult bovine oligodendrocytes: functional and pathological significance. Neurochemical Research. 2003;28:1385–1392. doi: 10.1023/a:1024952600774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lantos PL. The definition of multiple system atrophy: a review of recent developments. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 1998;57:1099–1111. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199812000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin WL, Lewis J, Yen SH, Hutton M, Dickson DW. Filamentous tau in oligodendrocytes and astrocytes of transgenic mice expressing the human tau isoform with the P301L mutation. American Journal of Pathology. 2003;162:213–218. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63812-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Shafit-Zagardo B, Aquino DA, Zhao ML, Dickson DW, Brosnan CF, et al. Cytoskeletal alterations in human fetal astrocytes induced by interleukin-1 beta. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1994;63:1625–1634. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63051625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LoPresti P, Szuchet S, Papasozomenos SC, Zinkowski RP, Binder LI. Functional implications for the microtubule-associated protein tau: localization in oligodendrocytes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1995;92:10369–10373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.22.10369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maroteaux L, Campanelli JT, Scheller RH. Synuclein: a neuron-specific protein localized to the nucleus and presynaptic nerve terminal. Journal of Neuroscience. 1988;8:2804–2815. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-08-02804.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeer PL, McGeer EG. The possible role of complement activation in Alzheimer disease. Trends in Molecular Medicine. 2002a;8:519–523. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(02)02422-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeer PL, McGeer EG. Inflammatory processes in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve. 2002b;26:459–470. doi: 10.1002/mus.10191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messing A, Brenner M. GFAP: functional implications gleaned from studies of genetically engineered mice. Glia. 2003;43:87–90. doi: 10.1002/glia.10219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monsonego A, Weiner HL. Immunotherapeutic approaches to Alzheimer’s disease. Science. 2003;302:834–838. doi: 10.1126/science.1088469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori F, Tanji K, Yoshimoto M, Takahashi H, Wakabayashi K. Demonstration of alpha-synuclein immunoreactivity in neuronal and glial cytoplasm in normal human brain tissue using proteinase K and formic acid pretreatment. Experimental Neurology. 2002;176:98–104. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.7929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller R, Heinrich M, Heck S, Blohm D, Richter-Landsberg C. Expression of microtubule-associated proteins MAP2 and tau in cultured rat brain oligodendrocytes. Cell and Tissue Research. 1997;288:239–249. doi: 10.1007/s004410050809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura S, Kawamoto Y, Nakano S, Akiguchi I, Kimura J. Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 and mitogen-activated protein kinase in glial cytoplasmic inclusions in multiple system atrophy. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 1998;57:690–698. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199807000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson PT, Soma LA, Lavi E. Microglia in diseases of the central nervous system. Annals of Medicine. 2002;34:491–500. doi: 10.1080/078538902321117698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura T, Ikeda K, Akiyama H, Arai T, Kondo H, Okochi M, et al. Glial tau-positive structures lack the sequence encoded by exon 3 of the tau protein gene. Neuroscience Letters. 1997;224:169–172. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(97)00161-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okochi M, Walter J, Koyama A, Nakajo S, Baba M, Iwatsubo T, et al. Constitutive phosphorylation of the Parkinson’s disease associated alpha-synuclein. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:390–397. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.1.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyanagi K, Makifuchi T, Ohtoh T, Chen KM, Gajdusek DC, Chase TN. Distinct pathological features of the gallyas- and tau-positive glia in the Parkinsonism-dementia complex and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis of Guam. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 1997;56:308–316. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199703000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papp MI, Kahn JE, Lantos PL. Glial cytoplasmic inclusions in the CNS of patients with multiple system atrophy (striatonigral degeneration, olivopontocerebellar atrophy and Shy-Drager syndrome) Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 1989;94:79–100. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(89)90219-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pramatarova A, Laganiere J, Roussel J, Brisebois K, Rouleau GA. Neuron-specific expression of mutant superoxide dismutase 1 in transgenic mice does not lead to motor impairment. Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;21:3369–3374. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-10-03369.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pronin AN, Morris AJ, Surguchov A, Benovic JL. Synucleins are a novel class of substrates for G protein-coupled receptor kinases. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:26515–26522. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003542200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter-Landsberg C. Organization and functional roles of the cytoskeleton in oligodendrocytes. Microscopy Research and Technique. 2001;52:628–636. doi: 10.1002/jemt.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter-Landsberg C, Gorath M, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. alpha-synuclein is developmentally expressed in cultured rat brain oligodendrocytes. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2000;62:9–14. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20001001)62:1<9::AID-JNR2>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen DR, Siddique T, Patterson D, Figlewicz DA, Sapp P, Hentati A, et al. Mutations in Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase gene are associated with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature. 1993;362:59–62. doi: 10.1038/362059a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein JD, Van Kammen M, Levey AI, Martin LJ, Kuncl RW. Selective loss of glial glutamate transporter GLT-1 in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Annals of Neurology. 1995;38:73–84. doi: 10.1002/ana.410380114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland LP, Shneider NA. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;344:1688–1700. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105313442207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy J, Minotti S, Dong L, Figlewicz DA, Durham HD. Glutamate potentiates the toxicity of mutant Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase in motor neurons by postsynaptic calcium-dependent mechanisms. Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18:9673–9684. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-23-09673.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw PJ, Eggett CJ. Molecular factors underlying selective vulnerability of motor neurons to neurodegeneration in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Journal of Neurology 247 Suppl. 2000;1:I17–I27. doi: 10.1007/BF03161151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimura H, Schlossmacher MG, Hattori N, Frosch MP, Trockenbacher A, Schneider R, et al. Ubiquitination of a new form of alpha-synuclein by parkin from human brain: implications for Parkinson’s disease. Science. 2001;293:263–269. doi: 10.1126/science.1060627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton AB, Farrer M, Johnson J, Singleton A, Hague S, Kachergus J, et al. alpha-synuclein locus triplication causes Parkinson’s disease. Science. 2003;302:841. doi: 10.1126/science.1090278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solano SM, Miller DW, Augood SJ, Young AB, Penney JB., Jr Expression of alpha-synuclein, parkin, and ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase L1 mRNA in human brain: Genes associated with familial Parkinson’s disease. Annals of Neurology. 2000;47:201–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillantini MG, Crowther RA, Jakes R, Cairns NJ, Lantos PL, Goedert M. Filamentous alpha-synuclein inclusions link multiple system atrophy with Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Neuroscience Letters. 1998;251:205–208. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00504-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stieber A, Gonatas JO, Gonatas NK. Aggregates of mutant protein appear progressively in dendrites, in periaxonal processes of oligodendrocytes, and in neuronal and astrocytic perikarya of mice expressing the SOD1(G93A) mutation of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2000;177:114–123. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(00)00351-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung JY, Kim J, Paik SR, Park JH, Ahn YS, Chung KC. Induction of neuronal cell death by Rab5A-dependent endocytosis of alpha-synuclein. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:27441–27448. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101318200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanji K, Imaizumi T, Yoshida H, Mori F, Yoshimoto M, Satoh K, et al. Expression of alpha-synuclein in a human glioma cell line and its up-regulation by interleukin-1beta. Neuroreport. 2001;12:1909–1912. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200107030-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JP, Hardy J, Fischbeck KH. Toxic proteins in neurodegenerative disease. Science. 2002;296:1991–1995. doi: 10.1126/science.1067122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teismann P, Tieu K, Cohen O, Choi DK, Wu du C, Marks D, et al. Pathogenic role of glial cells in Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders. 2003;18:121–129. doi: 10.1002/mds.10332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trotti D, Danbolt NC, Volterra A. Glutamate transporters are oxidant-vulnerable: a molecular link between oxidative and excitotoxic neurodegeneration? Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 1998;19:328–334. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(98)01230-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trotti D, Rolfs A, Danbolt NC, Brown RH, Jr, Hediger MA. SOD1 mutants linked to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis selectively inactivate a glial glutamate transporter. Nature Neuroscience. 1999;2:427–433. doi: 10.1038/8091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentine JS, Hart PJ. Misfolded CuZnSOD and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2003;100:3617–3622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730423100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Warrenburg BP, Lammens M, Lucking CB, Denefle P, Wesseling P, Booij J, et al. Clinical and pathologic abnormalities in a family with Parkinsonism and parkin gene mutations. Neurology. 2001;56:555–557. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Herpen E, Rosso SM, Serverijnen LA, Yoshida H, Breedveld G, van de Graaf R, et al. Variable phenotypic expression and extensive tau pathology in two families with the novel tau mutation L315R. Annals of Neurology. 2003;54:573–581. doi: 10.1002/ana.10721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakabayashi K, Hayashi S, Yoshimoto M, Kudo H, Takahashi H. NACP/alpha-synuclein-positive filamentous inclusions in astrocytes and oligodendrocytes of Parkinson’s disease brains. Acta Neuropathologica. 2000;99:14–20. doi: 10.1007/pl00007400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakabayashi K, Yoshimoto M, Tsuji S, Takahashi H. Alpha-synuclein immunoreactivity in glial cytoplasmic inclusions in multiple system atrophy. Neuroscience Letters. 1998;249:180–182. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00407-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenning GK, Tison F, Ben Shlomo Y, Daniel SE, Quinn NP. Multiple system atrophy: A review of 203 pathologically proven cases. Movement Disorders. 1997;12:133–147. doi: 10.1002/mds.870120203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong PC, Pardo CA, Borchelt DR, Lee MK, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, et al. An adverse property of a familial ALS-linked SOD1 mutation causes motor neuron disease characterized by vacuolar degeneration of mitochondria. Neuron. 1995;14:1105–1116. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90259-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama T, Kusunoki JI, Hasegawa K, Sakai H, Yagishita S. Distribution and dynamic process of neuronal cytoplasmic inclusion (NCI) in MSA: correlation of the density of NCI and the degree of involvement of the pontine nuclei. Neuropathology. 2001;21:145–154. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1789.2001.00390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zientek GM, Herman MM, Katsetos CD, Frankfurter A. Absence of neuron-associated microtubule proteins in the rat C-6 glioma cell line. A comparative immunoblot and immunohistochemical study. Neuropathology and Applied Neurobiology. 1993;19:346–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1993.tb00450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]