Immigrants and refugees are a vulnerable population in any country. Global migration has produced some 17 million “people of concern” worldwide, of whom well over half (10 million) are refugees. That there is a great potential for health problems in this population is evident: many have left countries that have limited health care resources and where diseases such as tuberculosis may be endemic. Further compounding their plight is the fact that many are not granted public health insurance in the countries that receive them and cannot afford to pay for health care expenses out of pocket. In this article, we discuss the mounting problem of medically uninsured immigrants, both globally and in Canada — an issue that gained prominence after the 2004 publication of a United Nations report.

In Europe, the problem is widespread. Between 1983 and 1997, 396 000 people entered the United Kingdom to seek refugee status or asylum. Most were granted temporary access to the National Health Services (NHS), pending determination of their claim. Typically, 75% of claims are subsequently refused, with an estimated 50%–75% staying, medically uninsured, in the country. Legislative plans in the UK to “close loopholes” and levy health care fees (including those for hospital, pregnancy and infant care) on failed asylum seekers threaten to worsen what has already been described as “patchy, belated and inappropriate” health care for this group (www.bma.org.uk/ap.nsf/Content/Asylumseekershealthdossier?OpenDocument&Highlight=2,asylum,seekers). Health concerns are readily apparent on both individual and public health levels: uninsured asylum seekers with HIV infection, for example, are not afforded NHS coverage, and over half of cases of tuberculosis occur among refugees and asylum seekers.

Similarly, in France, many immigrants and refugees otherwise entitled to national health insurance remain uninsured because they cannot surmount administrative barriers (e.g., the requirement for stable housing) and economic burdens (e.g., enrolment fees, substantial co-payments and insurance premiums). In France alone 1 million people, mostly immigrants and refugees, are estimated to be uninsured medically. Often in the lower socioeconomic strata, uninsured newcomers face greater difficulties than natives when they try to interact with the bureaucracies in the health system.1

In Canada, immigrants are admitted for their professional expertise and anticipated contribution to the workforce. In 2004 we admitted 204 000 landed immigrants and 31 000 refugees. Physicians in this country may be surprised to know that, despite Canada's universal health care system, many who reside here legally are never granted public health insurance. Other immigrants and refugees are granted coverage, but only after long delays: 4 provinces impose a mandatory 3-month waiting period — but in our experience, our patients' wait has averaged 2.1 years. Many others reside in limbo: between 1997 and 2004 Canada's Immigration and Refugee Board adjudicated 228 000 refugee claims, approving only 40%. Rejected refugee claimants who continue to reside in Canada while they pursue legal avenues of appeal lose their eligibility for public insurance, either provincial or federal. Up to 15% of the 29 000 claims backlogged during the same period are abandoned annually because of cost and delay (www.irb-cisr.gc.ca), which again leads to losses of Interim Federal Health Benefits.

What is the effect on immigrants and refugees of not having health insurance? The magnitude of the problem is difficult to appreciate because of the obstacles inherent to conducting research in this population. We were unable to find good data sources describing the size and demographics of this population in Canada. Nonetheless, there is some evidence that this vulnerable population experiences poor health outcomes. A study involving 1283 women from 10 European countries,2 for example, revealed that, compared with women born in their country of residence, foreign-born women were 3 times more likely to receive inadequate prenatal care; those without health insurance, however, were 19 times more likely. A study from Brussels3 found that of pregnant women who lacked health insurance, 46% received no antenatal care; moreover, perinatal deaths were increased 6-fold in this group: 58.4 (i.e., per 1000 births) versus 8.7, attributable primarily to a 7-fold increase in premature births.

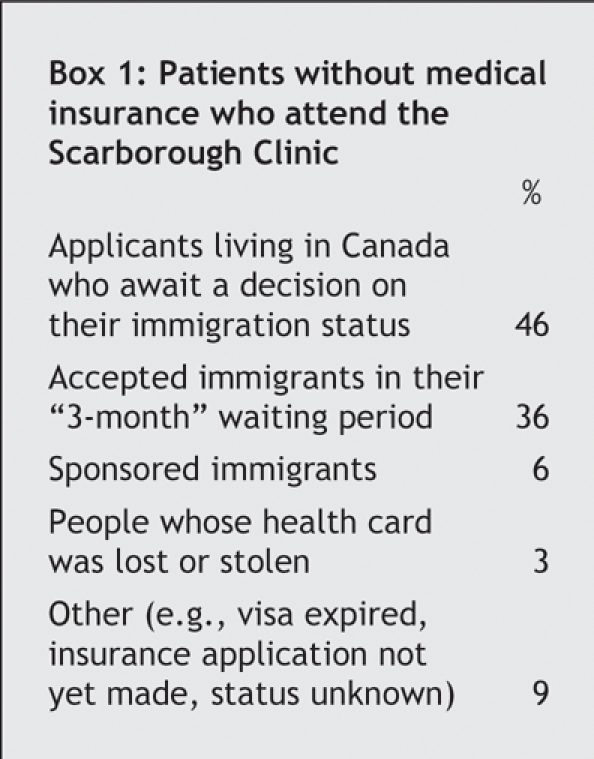

Our own experience of providing care for immigrants and refugees without health insurance is similar. In our clinic, where free health care is provided to all immigrants and refugees without health insurance (Box 1), the majority of attendees (66%) have been female; 17% of all patients sought maternity care. We found that 60% of pregnant women who have come to our clinic had deficiencies in prior antenatal care, having lacked adequate provider contact, pelvic examination, screening for diabetes or counselling about the use of folic acid. Mean gestational age at presentation is 23 weeks. Patients who present near term are delivered by a team of family doctors, midwives and obstetricians chosen according to the mother's risk factors.

Box 1.

It is unlikely that Canada's current policies on immigration and social and health care programs differ sufficiently from those of other countries to mitigate these poor health consequences for uninsured newcomers. Our patients regularly report being turned away by community health clinics because they do not meet enrolment requirements such as possession of identifying documents or evidence that they reside within the clinic's prescribed area. Such problems are common among people who are homeless or underhoused, or have lost their identifying documents or had them destroyed. In Toronto, many community health clinics have capacity restrictions that resulted in waiting lists to enrol. Some of our pregnant patients have reported being turned away when presenting at an advanced gestational age.

Delayed health care or denial of care at emergency departments because of inability to pay are also common themes. Our uninsured patients who require hospital care pose special challenges. Although our hospital has reduced fees and allows delayed payment from patients without health insurance, and our consultants donate their time, demand and costs nevertheless exceed our ability to respond, and some patients still do not receive medically necessary care. In some instances, uninsured immigrants have returned to their home country to access hospital care. Others who are entitled to health benefits lack the knowledge, documentation or means to secure them: 5% of our uninsured youth, mostly children born in Canada to uninsured newcomers, are in fact Canadian citizens.

Considerable numbers of immigrants and refugees reside legally in Canada without any entitlement to public health insurance. People in this population are much less likely to seek medical care.

More research is urgently needed to facilitate policy initiatives and solutions. Meanwhile, our preliminary research points to remedies that should be considered now. These include elimination of 3-month waiting periods in the provinces that require it; facilitation of health coverage for those who are eligible; improvements to the refugee claims process; implemention of emergency health insurance coverage for those in need while their claims are in process (pregnancy and newborn care, for example, are covered in Québec); and at community health clinics, increases in capacity and relaxion of enrolment criteria. If universal health insurance is a core Canadian value, we need to ensure that it is, indeed, universal.

Paul Caulford Department of Family Medicine and Community Services Medical Director Urban Outreach Family Medicine Centre Yasmin Vali Department of Family Medicine and Community Services The Scarborough Hospital Scarborough, Ont.

Acknowledgments

We thank Cathy Tersigni and Jennifer D'Andrade for their original and ongoing contributions to this research, as well as to the clinic. We also acknowledge contributions to this work by Neil Drummond (Calgary) and Drs. Richard Glazier, D'Arcy L. Little, Alan Li (Toronto) and Kevin Pottie (Ottawa). We also thank Linda Deng and Dr. Guilherme Coelho Dantas for their research support.

Footnotes

For supporting our clinical activities and research, we thank Community Care Access Centres Scarborough, Warden Woods Community Centre, Toronto Public Health, The Scarborough Hospital, the Department of Family and Community Medicine at the University of Toronto, the Canadian Institutes for Health Research and all our volunteers.

We helped found and continue to work in a clinic affiliated with the Department of Family Medicine and Community Services at The Scarborough Hospital that has provided free health care for medically uninsured immigrants and refugees since 2000. The clinic has recorded 7000 visits by 2000 patients from 85 countries of origin. All health care professionals at the clinic are volunteer workers.

Competing interests: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bollini P. Health policies for inmigrant populations in the 1990s: a comparative study in seven receiving countries. Int Migration Rev 1992;30: 103-19.

- 2.Delvaux T, Buekens P, Godin I, et al. Barriers to prenatal care in Europe. Am J Prev Med 2001;1:52-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Barlow P, Haumont D, Degueldre M. [Obstetrical and perinatal outcomes in patients not covered by medical insurance]. Rev Med Brux 1994;15: 366-70. [PubMed]