Abstract

The production of cyclic lipopeptides (CLPs) with antifungal and biosurfactant properties by Pseudomonas fluorescens strains was investigated in bulk soil and in the sugar beet rhizosphere. Purified CLPs (viscosinamide, tensin, and amphisin) were first shown to remain highly stable and extractable (90%) when applied (ca. 5 μg g−1) to sterile soil, whereas all three compounds were degraded over 1 to 3 weeks in nonsterile soil. When a whole-cell inoculum of P. fluorescens strain DR54 containing a cell-bound pool of viscosinamide was added to the nonsterile soil, declining CLP concentrations were observed over a week. By comparison, addition of the strains 96.578 and DSS73 without cell-bound CLP pools did not result in detectable tensin or amphisin in the soil. In contrast, when sugar beet seeds were coated with the CLP-producing strains and subsequently germinated in nonsterile soil, strain DR54 maintained a high and constant viscosinamide level in the young rhizosphere for ∼2 days while strains 96.578 and DSS73 exhibited significant production (net accumulation) of tensin or amphisin, reaching a maximum level after 2 days. All three CLPs remained detectable for several days in the rhizosphere. Subsequent tests of five other CLP-producing P. fluorescens strains also demonstrated significant production in the young rhizosphere. The results thus provide evidence that production of different CLPs is a common trait among many P. fluorescens strains in the soil environment, and further, that the production is taking place only in specific habitats like the rhizosphere of germinating sugar beet seeds rather than in the bulk soil.

The use of microbial antagonists against plant-pathogenic microfungi in agricultural crops has been proposed as a supplement or alternative to chemical fungicide treatment. In the search for effective biocontrol organisms, the antagonistic traits of antibiotic-producing Pseudomonas strains have recently been studied intensively, including a strong focus on the regulation of antibiotic production (3, 15, 19, 20). For instance, nutrient limitation has been suggested to be a constraint of antibiotic production (25), and nutrient-rich microsites, such as the spermosphere surrounding germinating seeds or the rhizosphere surrounding seedling roots, are likely to support antibiotic production in natural soil (22, 25). Still, little is known about antibiotic production under complex in situ conditions in the rhizosphere. Variable production, chemical instability, and low detection sensitivity for the antibiotics have so far made the study of their in situ production in soil very difficult (22).

Thomashow et al. (22) first detected production of the antibiotic phenazine in soil inoculated with the Pseudomonas fluorescens biocontrol strain 2-79, thus demonstrating that suppression of take-all disease was directly related to antibiotic production in the natural rhizosphere. Similarly, the antibiotic diacetyl phloroglucinol (DAPG) was recently detected and quantified in the natural wheat rhizophere spiked with the P. fluorescens biocontrol strain Q2-87 (2), and indigenous production of DAPG was demonstrated to be important in soil suppressive of take-all disease (18). Production of iturin A and surfactin antibiotics by Bacillus subtilis RB14 was detected in a sterilized vermiculite-soil system (1), and xanthobaccin A was produced by Stenotrophomonas sp. strain SB-K88 in the sugar beet rhizosphere using a hydroponic system (12). The latter compounds represent cyclic lipopeptides (CLPs), and the reports have given evidence for their production in bulk soil and the rhizosphere.

During recent years, we have observed that fluorescent Pseudomonas spp. produce a number of different CLPs which may be useful for biological control. For instance, we have found that CLP production is a common trait among fluorescent Pseudomonas spp. isolated from the sugar beet rhizosphere in certain soils (16) and that all of the CLPs identified here contained either 9 or 11 amino acids in the peptide ring structure and a C10 fatty acid moiety at one of the amino acids (16). The P. fluorescens strains DR54, 96.578, and DSS73 studied in the present work produce three different CLPs, viscosinamide (16), tensin (5), and amphisin (21), all showing antagonistic activities against the important plant-pathogenic microfungi Pythium ultimum (13, 15, 23) and Rhizoctonia solani (16, 17). In other studies, it was shown that viscosinamide production is coupled to primary metabolism and cell proliferation in the producing bacteria and thus is controlled by growth substrate and nutrient conditions (14, 15). Viscosinamide has a strong cell-binding affinity to the producing cells of strain DR54 (15), while both tensin and amphisin, produced in strains 96.578 and DSS73, are largely released into the surrounding medium (reference 17 and unpublished data). In a recent study, it was shown that amphisin is produced when the cells enter stationary phase, and further, that the amphisin synthetase gene (amsY) is controlled by the two-component regulatory system GacA/GacS (8). The amphisin-producing strain DSS73 was originally isolated from the sugar beet rhizosphere, and pure-culture studies have shown that the GacA/GacS regulation of both amsY expression and amphisin production is significantly stimulated by an unidentified compound extractable from sugar beet seeds (8). To determine if CLP production by Pseudomonas sp. strains takes place in natural soil environments, we present here a study of CLP production (net accumulation) in bulk soil and the sugar beet rhizosphere using different strains of Pseudomonas spp.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microorganisms and soil.

Inocula of all P. fluorescens strains were prepared by overnight growth (28°C) in Luria broth containing (per liter) 10 g of Bacto Tryptone, 5 g of yeast extract, 10 g of NaCl, and 1 g of glucose, pH 7.2. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 7,000 × g (10 min; 4°C) and washed twice in sterile 0.9% NaCl. To determine the numbers of fluorescent Pseudomonas sp. bacteria in the bulk soil and rhizosphere systems, CFU counts were made on Pseudomonas-specific Gould's S1 plates containing (per liter) 10 g of sucrose, 10 ml of glycerol, 5 g of Casamino Acids, 1 g of NaHCO3, 1 g of MgSO4 · 7H2O, 2.3 g of K2HPO4, 1.2 g of Na-lauryl sarcosin, and 15 g of agar (4). After the medium was autoclaved, 5 ml of a trimethoprim solution liter−1 containing 100 mg of trimethoprim (T-7883; Sigma), 8.5 ml of methanol, and 16.5 ml of Milli-Q water was added.

In earlier work, two major groups of P. fluorescens strains producing different types of CLPs were identified among isolates from the sugar beet rhizosphere (16). The isolates were grouped according to their production of amphisin-like CLPs (group A), including amphisin (A1; represented in this work by P. fluorescens DSS73), lokisin (A2; represented by P. fluorescens CTS41), hodersin (A3; represented by P. fluorescens CTS17), and tensin (A4; represented by P. fluorescens 96.578), or of viscosinamide-like CLPs (group V), including viscosinamide (V1; represented by P. fluorescens DR54), an unnamed compound with an Mw of 1,125.0 (V2; represented by P. fluorescens CTS37), two unnamed compounds with Mws of 1,125.0 and 1,153.6 (V3; represented by P. fluorescens CTS38), and an unknown compound with an Mw of 1,139.2 (V4; represented by P. fluorescens DSS2). The CLP structures differ mainly in the peptide moieties, where A- and V-type compounds contain either 11 or 9 variable amino acids, respectively.

Soil was collected from a fallow field at the Højbakkegård experimental station (Tåstrup, near Copenhagen, Denmark) and kept at 5°C until it was used. The soil was homogenized through a 2-mm-mesh screen, and the water content of the soil was adjusted 2 days before experiments. In experiments where purified CLPs were added to the soil, the water content was adjusted to 12 to 13% (wt/wt) by spraying the soil with tap water and gently mixing it in a polyethylene bag. In experiments where CLP-producing strains were added to the soil, the water content was initially adjusted to 10% but subsequently reached 12% by addition of the bacterial inoculum. Finally, in control experiments, 0.5 kg of soil was autoclaved for 1 h during each of three consecutive days. The water content was also adjusted by spraying the soil with sterile water, and 5 g of soil (wet weight) was eventually transferred into 25-ml glass bottles with Teflon-lined screw caps and autoclaved again for 1 h.

Recovery of purified viscosinamide, tensin, and amphisin added to bulk soil system.

Purified viscosinamide, tensin, and amphisin were extracted from cultures of P. fluorescens DR54, 96.578, and DSS73 as described earlier (15, 17, 21). The extraction efficacy (recovery) for viscosinamide in soil was tested by adding 0.05, 0.08, 0.1, 0.5, and 1 μg of purified viscosinamide (∼90% purity) g of soil−1 in 10 μl of methanol solution to 5 g of sterile bulk soil (soil without plants); 10 μl of methanol was added to other soil samples for control. In parallel extraction experiments, the recovery of tensin and amphisin was tested by adding 0.06, 0, 11, 0.26, 0.30, 0.51, 0.93, and 1.14 μg of tensin (∼90% purity) g of soil−1 and 0.09, 0.15, 0.28, 0.33, 0.62, 0.86, and 1.10 μg of amphisin (∼90% purity) g of soil−1 in 10 μl of methanol solution to 5 g of sterile bulk soil; a control treated with 10 μl of methanol was again included for comparison. The soils were incubated for 1 h at 20°C. In other experiments, the long-term stabilities of viscosinamide, tensin, and amphisin during extended incubation were investigated in both sterile and nonsterile soil samples by applying 10 μl of methanol solution containing 25 μg of purified CLP to 5-g samples of soil; a control soil with 10 μl of methanol was included. These soils were then incubated for 2 weeks at 20°C, and samples were sacrificed and analyzed at intervals.

Extraction of CLPs was done with 20 ml of acetonitrile (high-performance liquid chromatography [HPLC] grade; Labscan Ltd., Dublin, Ireland) containing 3.8 mM trifluoroacetic acid (4:1 [vol/vol]) as suggested by Asaka and Shoda (1). One hour of vigorous rotary shaking (200 rpm) was performed before the soil particles were allowed to settle for 15 min. The organic phase was then collected and weighed in Teflon centrifuge tubes before being evaporated to dryness by vacuum centrifugation. The residue was subsequently dissolved in methanol and frozen for later analysis. Before HPLC analysis, impurities were precipitated by centrifugation at 20,000 × g (10 min; 4°C). CLP concentrations were analyzed by HPLC using a Hewlett-Packard model 1100 with a diode array detector and a LiChroCART 250-4 HPLC cartridge containing a LiChrosphere 100 RP-18 (5-μm) column held at 40°C. For viscosinamide analysis, acetonitrile (HPLC grade) and 0.1% O-phosphoric acid were mixed in a multistep gradient protocol including 20 to 55% acetonitrile (0 to15 min), 55 to 99% acetonitrile (15 to 21 min), and 99% acetonitrile (21 to 26 min); the flow rate was 1 ml min−1. For tensin and amphisin analyses, acetonitrile (HPLC grade) and 0.1% O-phosphoric acid were mixed in a multistep gradient protocol including 50 to 65% acetonitrile (0 to 13 min), 65 to 99% acetonitrile (13 to 24 min), and 99% acetonitrile (24 to 26 min); the flow rate was 1 ml min−1. In both methods, absorbance was determined at 210 ± 8 nm, and chromatograms were analyzed by the HP Chemstation software package. Background signals from control soils without CLPs or inoculant bacteria added were subtracted, and CLP concentrations were calculated using purified compounds as standards.

Strains DR54, 96.578, and DSS73 added to bulk soil systems.

The strains DR54, 96.578, and DSS73 and their CLP production were followed after the addition of washed inoculum directly to sterile and nonsterile bulk soil samples. The inoculum density was adjusted to obtain ∼1 × 108 to 5 × 108 cells g of dry soil−1 and a final water content of 12 to 13%. Sterile soil samples were spiked by pipetting the inoculum directly into 5 g of soil in 25-ml glass bottles. Nonsterile soil was spiked with either of the strains by spraying the inoculum into a polyethylene bag with 500 g of soil while gently mixing them. NaCl solution (0.9%) was added to a control soil, and 5-g subsamples of the inoculated soil were subsequently weighed into 25-ml glass bottles. All soils were incubated for 1 to 2 weeks at 20°C.

On each sampling occasion, triplicate bottles with soil were extracted with 10 ml of 0.9% NaCl to determine the CFU counts on Gould's S1 plates (4). The bacterial-extraction protocol included 1 min of vortexing before the sample was submerged in an ultrasonic bath for 0.5 min. Among the colonies of fluorescent Pseudomonas spp. appearing after ∼48 h on the Gould's S1 plates, strain DR54 was identified using a colony-blotting protocol with a strain-specific antibody which targeted the lipopolysaccharide component of strain DR54 (9). Strain 96.578 was identified using a PCR fingerprint method (10) in which 10 colonies from a Gould's S1 plate containing >50 colonies were randomly isolated before their PCR profiles were determined (10). The percentage of isolates matching the PCR profile of strain 96.578 was used to calculate the CFU count for the strain in the soil. Strain DSS73 was marked with green fluorescent protein by a Tn7 insertion (7), allowing the DSS73 colonies to be spotted by green fluorescence or kanamycin resistance when randomly transferred onto kanamycin-amended (25 μg ml−1) Luria broth agar plates. Finally, the CLP concentrations in the soil samples were followed by triplicate sampling, extraction, and HPLC analysis as described above for experiments with purified CLPs.

Strains DR54, 96.578, and DSS73 added to sugar beet seeds.

In rhizosphere systems, 50 g of nonsterile soil with a preadjusted water content of 12% was weighed into a 50-ml centrifuge tube and compacted to a density of 1.1 g of soil cm−3 by gently tapping the tube. Approximately 1,500 sugar beet seeds were added to a suspension of bacterial inoculum (∼1010 cells ml−1 in 0.9% NaCl) and vigorously shaken for 30 min; the seeds shaken in sterile 0.9% NaCl solution were used as a control. Using sterile tweezers, three seeds were placed in each 50-ml polyethylene centrifuge tube filled with soil. The tubes were subsequently incubated uncapped in a transparent polyethylene bag to reduce evaporation while maintaining aeration. The samples were aerated daily by opening the bags. Incubation was for 1 week at 20°C, and cycles of 14 h in light and 10 h in darkness per day were applied.

Inoculant population densities (CFU per seed) were determined during the first week after sowing. The sample on day zero represented the initial population on the seeds before sowing. In the period before germination (days 1 and 2), 10 of the seeds retrieved were pooled for extraction in 5 ml of sterile 0.9% NaCl. After seed germination (days 4 and 6), 10 seedlings were gently removed from the soil, and pooled samples representing both seeds and roots together with adhering rhizosphere soil were extracted in 10 ml of 0.9% NaCl. On day 6, the seed cap was typically detached from the seedling, but if still attached to the root it was collected and included in the extraction. On each sampling occasion, triplicates of 10 seeds or seedlings were used. The standardized extraction and identification protocol for the added strains was the same as in the bulk soil experiment. Viscosinamide, tensin, and amphisin concentrations in the rhizosphere system were determined after extraction in a bulk sample of 50 seeds or seedlings, including roots with adhering rhizosphere soil.

CLP production by other P. fluorescens strains added to sugar beet seeds.

To compare CLP production by representatives of strains from the amphisin (A) and viscosinamide (V) groups, we performed a 2-day incubation in the rhizosphere system, using a simple setup with 80 g of soil (water content, 12%) weighed into a 9-cm-diameter petri dish and compacted to 1.1 g of soil cm−3. For each CLP-producing strain, ∼800 sugar beet seeds were coated as described above. Using sterile tweezers, 15 seeds were placed in a 9-cm-diameter petri dish filled with soil. The dishes were subsequently incubated in a transparent polyethylene bag to reduce evaporation while maintaining aeration. The incubation period was 2 days at 20°C, with cycles of 14 h in light and 10 h in darkness per day. Inoculant populations (CFU per seed) were determined on days 0 and 2 as described above for strains DR54, 96.578, and DSS73. CFU counts of the applied CLP-producing strains were obtained directly without any tagging procedure, since control seeds without CLP-producing strains had 100 to 1,000 times fewer CFU counts on Gould's S1 medium. CLP concentrations in the germinating seed environment were determined as described above.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Recovery of viscosinamide, tensin, and amphisin added to soil and rhizosphere systems.

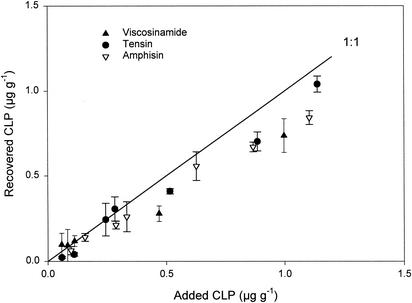

The production of CLPs with antibiotic and biosurfactant properties has been found in different microorganisms isolated from different environments (1, 6, 15). The most attention has been paid to studying CLP production under variable growth conditions in vitro (14, 15), and only a few studies (1, 12) have so far focused on the in situ production and stabilities of the CLP compounds in complex environments, such as bulk soil and the rhizosphere. When studying CLP production in such complex environments, a major concern is the reproducibility of the extraction and detection protocol. In this work, a number of protocols were tested, but extraction with acetonitrile in 3.8 mM trifluoroacetic acid (1) always gave the highest recovery for all CLPs in soil samples (data not shown), and it was therefore chosen for subsequent experiments. As seen in Fig. 1, extraction of viscosinamide, tensin, and amphisin added to sterile bulk soil gave a recovery of ∼80% for concentrations of 0.05 to 1 μg of CLP g of soil−1. Similar recoveries of 70 to 90% were observed by Asaka and Shoda (1) addressing the CLPs surfactin and iturin A in sterile vermiculite-soil systems. We also found detection limits for viscosinamide, tensin, and amphisin in bulk soil of ∼0.06, 0.05, and 0.09 μg g of dry soil−1, respectively, which are comparable to the detection limits for other microbial antibiotics in soil related to biological control, e.g., DAPG (2) and phenazine-1-carboxylic acid (22).

FIG. 1.

Extraction efficacies of different amounts of purified CLPs—viscosinamide, tensin, and amphisin—added to sterile soil. All data are means ± standard deviations (n = 3).

Stabilities of purified viscosinamide, tensin, and amphisin added to sterile and nonsterile bulk soil systems.

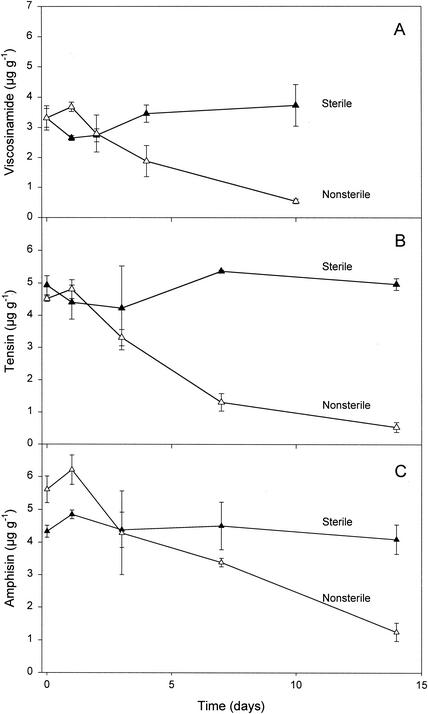

The long-term stabilities of CLPs were tested when purified compounds were added at ∼5 μg g−1 and incubated for 2 weeks in sterile and nonsterile bulk soils. As shown in Fig. 2, the viscosinamide, tensin, and amphisin concentrations remained nearly constant over 10 days in the sterile soil. However, in the nonsterile soil, the added viscosinamide concentration remained high for ∼2 days, while both the tensin and amphisin concentrations were constant for ∼1 day before they declined over the subsequent incubation period (Fig. 2B and C). Approximately 50% of the initial viscosinamide and tensin concentrations was left after 5 days, while ∼50% of the initial amphisin was left after 10 days, suggesting that CLPs were biodegraded by the indigenous microorganisms within a few weeks. In comparable experiments with sterile soil, Asaka and Shoda (1) found different adsorptive properties of the CLPs surfactin and iturin A. In these experiments, a B. subtilis strain produced both surfactin and iturin A in the sterile soil, but whereas surfactin levels remained high for several days, iturin A concentrations soon declined due to leaching, degradation, or chemical binding to the soil particles (1). To determine if chemical degradation or irreversible binding to soil particles also affected the stabilities of the P. fluorescens CLPs viscosinamide, tensin, and amphisin, all of the compounds were added to sterile bulk soil (Fig. 2). None of them were degraded chemically, however, and all remained fully extractable during a 2-week incubation period.

FIG. 2.

Stabilities of purified CLPs—viscosinamide (A), tensin (B), and amphisin (C)—added to sterile and nonsterile bulk soil. All data are means ± standard deviations (n = 3).

Lack of CLP production by whole-cell inocula in bulk soil systems.

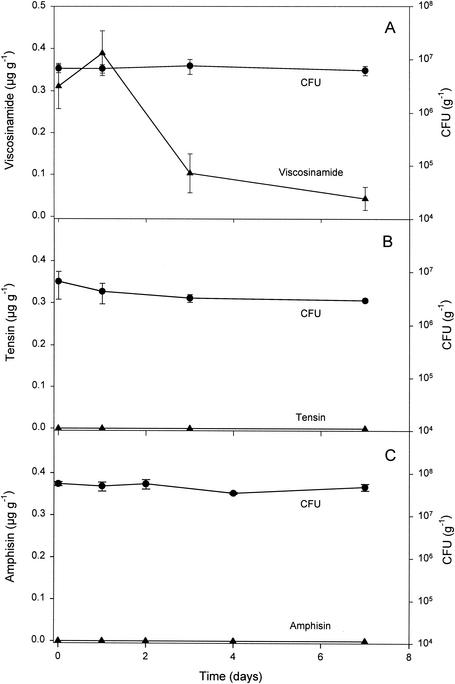

Immediately (day zero) after P. fluorescens DR54 inoculum was added to the bulk soil at a level of 6.3 × 107 CFU g−1, ∼30% of the added population was still extractable and culturable on Gould's S1 medium (Fig. 3A). During the 1-week incubation, ∼60% of the initial CFU remained viable after 1 week of incubation. The amount of viscosinamide in the inoculum was calculated to provide an initial viscosinamide concentration of 0.3 μg g of dry soil−1, which corresponded well to the measured concentration on the first sampling occasion (day zero). On day 1, the concentration still remained high in the soil, but then it declined to 17% over the next few days. The amount of viscosinamide expressed per CFU of strain DR54 only transiently remained high in the soil (until after day 1), again suggesting that rapid microbial degradation of the compound took place. From earlier studies in pure culture, we had no indications that viscosinamide was degraded by the producing strain per se, even after extended incubation periods (data not shown). We therefore concluded that indigenous soil microorganisms must have degraded the viscosinamide in the soil.

FIG. 3.

Population dynamics and CLP production in nonsterile bulk soil inoculated with P. fluorescens strains DR54 (A), 96.578 (B), and DSS73 (C). All data are means ± standard deviations (n = 3).

When P. fluorescens strains 96.578 and DSS73 were added to bulk soil, the CFU counts were nearly constant over a 1-week period, as shown in Fig. 3B and C. Unlike viscosinamide, the tensin and amphisin compounds produced by these strains show only limited binding to the producing cells (17), and washing the inocula before adding them to the soil therefore results in very low initial CLP concentrations. The calculated initial tensin concentration was thus 8 ng g of dry soil−1 on day zero, which was below the detection limit in the soil (∼60 ng g of dry soil−1). Figure 3B further shows that the tensin concentrations remained undetectable during the whole incubation period of ∼1 week, indicating that CLP production (if present) was too low to match degradation. Similarly, the addition of P. fluorescens strain DSS73 to the soil resulted in no detectable amphisin production (Fig. 3C). Even in a different batch of soil, where we observed increasing CFU for both 96.578 and DSS73, reaching ∼2 × 108 per g of soil on day 3, we found no detectable CLP production (data not shown).

Production and transient accumulation of CLPs in the sugar beet rhizosphere.

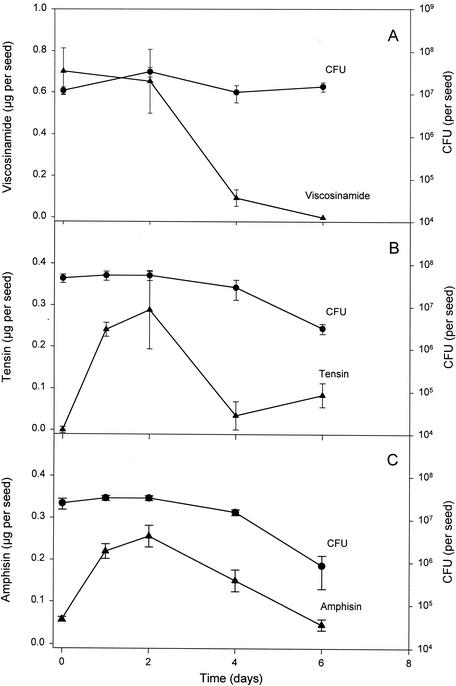

All three P. fluorescens strains, DR54, 96.578, and DSS73, were initially selected as being capable of antagonizing P. ultimum and R. solani on plates and during the early seed germination and root development of sugar beets (13, 15, 16, 17, 23, 24). When looking for antibiotics involved in this antagonistic activity in vitro, it has been shown that purified CLPs from these three strains have inhibitory activity toward both P. ultimum and R. solani (15, 16, 17). A prerequisite for CLP production to be involved in fungal inhibition in soils is that the P. fluorescens strains be active and produce the CLP compounds after sugar beet seeds are coated with the bacteria. Soil experiments were thus conducted to monitor both CFU counts and CLP production of P. fluorescens inocula on sugar beet seeds during a 6-day incubation period. During this period of initial seed germination, the CFU counts of strain DR54 remained nearly constant (Fig. 4A). These results are supported by CFU counts in an earlier study by Thrane et al. (23) showing that strain DR54 was able to colonize both the root base and the root tip when sugar beet seedlings were grown in soil microcosms. In addition, detailed confocal laser scanning microscopy images of the roots have revealed that a subpopulation of the inoculant strain DR54 may remain active for at least 3 weeks on the surfaces of young sugar beet roots (11). For CLP production, strain DR54 is unique in its high accumulation of the CLP viscosinamide in the cell wall (15). On day zero, the concentration of viscosinamide detected was ∼0.70 μg per seed, representing the significant pool of cell-bound CLP in the DR54 inoculum. This concentration was also found on the germinating seeds retrieved on day 2, but thereafter a decline in the viscosinamide concentration occurred as in the bulk soil, and the detection limit was reached on day 6.

FIG. 4.

Population dynamics and CLP production in nonsterile rhizosphere systems inoculated with P. fluorescens strains DR54 (A), 96.578 (B), and DSS73 (C). Inoculant populations were added to sugar beet seeds sown on day zero. All data are means ± standard deviations (n = 3).

When strains 96.578 and DSS73 were applied to the sugar beet seeds, both strains were found to have high viability both on the seeds and in the young rhizosphere (Fig. 4B and C). Initially, 2 × 107 to 5 × 107 CFU was inoculated per seed, and the two populations appeared constant for the first 2 days before a decline was observed. In contrast to viscosinamide, the CLPs tensin and amphisin show no significant binding to the producing cells, and the inoculant bacteria thus provide only a negligible increment of CLP on the seeds. The initial (day zero) tensin concentration was thus below the detection limit but soon increased to 0.29 μg per seed on day 2. Similarly, the amphisin concentration was initially only 0.06 μg per seed but increased to 0.26 μg per seed after 2 days. After these transient accumulations, both tensin and amphisin concentrations again declined and eventually reached ∼0.05 to 0.08 μg of CLP per seed on day 6. The results demonstrated an early phase of in situ production (net accumulation) of tensin and amphisin by the inoculated strains 96.578 and DSS73 when sugar beet seed germination took place and the viability of the inocula was high and constant. This important information confirms an earlier observation from in vitro studies in agar medium that strain 96.578 produces tensin during seed germination (17). This information also supports earlier in vitro studies in liquid medium showing that amphisin production may be significantly stimulated by a compound(s) released from the sugar beet seeds (8).

Survey of CLP production among P. fluorescens strains isolated from the sugar beet rhizosphere.

In some soils, the frequency of CLP-producing P. fluorescens strains is very high within the overall P. fluorescens population (16). In a recent survey of ∼170 CLP-producing strains, all demonstrated biosurfactant activity and a majority showed antagonistic activity against the two plant-pathogenic fungi P. ultimum and R. solani (16). When several representatives of these strains were tested by applying a panel of CLP-producing strains to sugar beet seeds, the CFU remained ∼5 × 107 per seed, and all strains produced CLP concentrations on the germinating seed of 0.2 to 0.6 μg per seed recorded on day 2 (Table 1). All strains except those representing groups V1 (producing viscosinamide) and V4 (producing a compound with an Mw of 1,139.2) (16) contained no or insignificant levels of cell-bound CLP in the inoculum (data not shown). The results therefore document that in situ production of the CLPs actually occurs on the germinating seed in soil, using several different P. fluorescens strains as inocula. These results further imply that the observed tensin and amphisin production on the germinating sugar beet seeds in soil was also valid for P. fluorescens strains producing other types of CLP compounds.

TABLE 1.

CLP concentrations on nonsterile sugar beet seeds after 2 days of incubation at 20°Ca

| P. fluorescens strain groupb | CLP compound | CLP concn (μg per seed) |

|---|---|---|

| A1 | Amphisin | 0.36 ± 0.10 |

| A2 | Lokisin | 0.22 ± 0.20 |

| A3 | Hodersin | 0.56 ± 0.05 |

| A4 | Tensin | 0.29 ± 0.09 |

| V1c | Viscosinamide | 0.65 ± 0.15 |

| V2 | Mw 1,125.0d | 0.52 ± 0.17 |

| V3 | Mw 1,125.0 | 0.38 ± 0.01 |

| Mw 1,153.6 | 0.30 ± 0.01 | |

| V4c | Mw 1,139.2 | 0.57 ± 0.12 |

Sugar beet seeds were inoculated with P. fluorescens strains on day zero. All data are means ± standard deviations (n = 3).

Strain groups were classified according to CLP production (2).

Strain containing cell-bound CLP.

Molecular weights are given for unnamed compounds.

Apart from fungal antagonism and reduction of surface tension detected in vitro (16), other possible functions of the CLPs for rhizosphere-inhabiting P. fluorescens strains remain speculative at this stage. Pure-culture studies of strain DSS73 have shown that a growth-inhibitory activity in sugar beet extract may be relieved by amphisin, indicating that this CLP may in some way protect the inoculant from growth arrest or improve nutrient availability in the rhizosphere (8). Based on these in vitro results, it may be speculated that the in situ production of CLPs on sugar beet seeds in soil is advantageous to the P. fluorescens inoculants during their growth activity in the rhizosphere.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Danish Agricultural and Veterinary Research Council (journal no. 9702796) and the Danish Ministry of Agriculture (contract no. 93S-2466-Å95-00788) in cooperation with Danisco Seeds A/S and NOVO-Nordisk A/S.

We thank Elisabeth Koluda, Kirsten Ploug, and Dorte Rasmussen for excellent technical assistance, Birgit Koch for providing strain DSS73 marked with Tn7, Ole Nybroe for providing protocols for immunodetection of strain DR54, and Peter Stephensen Lübeck for assistance in PCR fingerprinting analysis of strain 96.578.

REFERENCES

- 1.Asaka, O., and M. Shoda. 1996. Biocontrol of Rhizoctonia solani damping-off of tomato with Bacillus subtilis RB14. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:4081-4085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonsall, R. F., D. M. Weller, and L. S. Thomashow. 1997. Quantification of 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol produced by fluorescent Pseudomonas spp. in vitro and in the rhizosphere of wheat. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:951-955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duffy, B. K., and G. Défago. 1999. Environmental factors modulating antibiotic and siderophore biosynthesis by Pseudomonas fluorescens biocontrol strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:2429-2438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gould, W. D., C. Hagedorn, T. R. Bardinelli, and R. M. Zablotowicz. 1985. New selective media for enumeration and recovery of fluorescent pseudomonads from various habitats. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 49:28-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henriksen, A., U. Anthoni, T. H. Nielsen, J. Sørensen, C. Christophersen, and M. Gajhede. 2000. Cyclic lipoundecapeptide Tensin from Pseudomonas fluorescens strain 96.578. Acta Crystallogr. C 56:113-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katz, E., and A. L. Demain. 1977. The peptide antibiotics of Bacillus: chemistry, biogenesis and possible functions. Bacteriol. Rev. 41:449-474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koch, B., E. J. Jensen, and O. Nybroe. 2001. A panel of TN7-based vectors for insertion of the gfp marker gene or for delivery of cloned DNA into Gram-negative bacteria at a neutral chromosomal site. J. Microbiol. Methods 45:187-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koch, B., T. H. Nielsen, D. Sørensen, J. B. Andersen, C. Christophersen, S. Molin, M. Givskov, J. Sørensen, and O. Nybroe. 2002. Lipopeptide production in Pseudomonas sp. strain DSS73 is regulated by components of sugar beet exudates via the Gac two-component regulatory system. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:4509-4516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kragelund, L., K. Leopold, and O. Nybroe. 1996. Outer membrane protein heterogeneity within Pseudomonas fluorescens and P. putida and use of an OprF antibody as a probe for rRNA homology group I pseudomonads. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:480-485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Lübeck, M., I. A. Alekhina, P. S. Lübeck, D. F. Jensen, and S. A. Bulat. 1999. Delineation of Tricoderma harzinaum into two different genotypic groups by a highly robust fingerprinting method, UP-PCR, and UP-PCR product cross hybridization. Mycol. Res. 103:289-298. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lübeck, P. S., M. Hansen, and J. Sørensen. 2000. Simultaneous detection of the establishment of seed-inoculated Pseudomonas fluorescens strain DR54 and native soil bacteria on sugar beet root surfaces using fluorescence antibody and in situ hybridization techniques. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 33:11-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakayama, T., Y. Homma, Y. Hashidoko, J. Mizutani, and S. Tahara. 1999. Possible role of xanthobaccins produced by Stenotrophomonas sp. strain SB-K88 in suppression of sugar beet damping-off disease. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:4334-4339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nielsen, M. N., J. Sørensen, J. Fels, and H. C. Pedersen. 1998. Secondary metabolite- and endochitinase-dependent antagonism toward plant-pathogenic microfungi of Pseudomonas fluorescens isolates from sugar beet rhizosphere. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:3563-3569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nielsen, T. H., C. Christophersen, U. Anthoni, and J. Sørensen. 1998. A promising new metabolite from Pseudomonas fluorescens for biocontrol of Pythium ultimum and Rhizoctonia solani. IOBC/WPRS Bull. 21:51-55.

- 15.Nielsen, T. H., C. Christophersen, U. Anthoni, and J. Sørensen. 1999. Viscosinamide, a new cyclic depsipeptide with surfactant and antifungal properties produced by Pseudomonas fluorescens DR54. J. Appl. Microbiol. 86:80-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nielsen, T. H., D. Sørensen, C. Tobiasen, J. B. Andersen, C. Christophersen, M. Givskov, and J. Sørensen. 2002. Antibiotic and biosurfactant properties of cyclic lipopeptides produced by fluorescent Pseudomonas spp. from the sugar beet rhizosphere. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:3416-3423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nielsen, T. H., C. Thrane, C. Christophersen, U. Anthoni, and J. Sørensen. 2000. Structure, production characteristics and fungal antagonism of tensin—a new antifungal cyclic lipopeptide from Pseudomonas fluorescens strain 96.578. J. Appl. Microbiol. 89:992-1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raaijmakers, J. M., R. F. Bonsall, and D. M. Weller. 1999. Effect of population density of Pseudomonas fluorescens on production of 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol in the rhizosphere of wheat. Biol. Control 89:470-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shanahan, P., D. J. O'Sullivan, P. Simpson, J. D. Glennon, and F. O'Gara. 1992. Isolation of 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol from a fluorescent pseudomonad and investigation of physiological parameters influencing its production. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:353-358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slininger, P. J., and M. A. Jackson. 1992. Nutritional factors regulating growth and accumulation of phenazine 1-carboxylic acid by Pseudomonas fluorescens 2-79. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 37:388-392. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sørensen, D., T. H. Nielsen, C. Christophersen, J. Sørensen, and M. Gajhede. 2001. Cyclic lipoundecapeptide amphisin from Pseudomonas sp. strain DSS73. Acta Crystallogr. C 57:1123-1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomashow, L. S., D. M. Weller, R. F. Bonsall, and L. S. Pierson III. 1990. Production of the antibiotic phenazine-1-carboxylic acid by fluorescent Pseudomonas species in the rhizosphere of wheat. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:908-912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thrane, C., T. H. Nielsen, M. N. Nielsen, S. Olsson, and J. Sørensen. 2000. Viscosinamide-producing Pseudomonas fluorescens DR54 exerts biocontrol effect on Pythium ultimum in sugar beet rhizosphere. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 33:139-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thrane, C., T. H. Nielsen, J. Sørensen, and S. Olsson. 2001. Pseudomonas fluorescens DR54 reduces sclerotia formation, biomass development, and disease incidence of Rhizoctonia solani causing damping-off in sugar beet. Microbiol. Ecol. 42:438-445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams, S. T. 1982. Are antibiotics produced in soil? Pedobiologia 23:427-435. [Google Scholar]