Abstract

Analysis of Cryptosporidium occurrence in six watersheds by method 1623 and the integrated cell culture-PCR (CC-PCR) technique provided an opportunity to evaluate these two methods. The average recovery efficiencies were 58.5% for the CC-PCR technique and 72% for method 1623, but the values were not significantly different (P = 0.06). Cryptosporidium oocysts were detected in 60 of 593 samples (10.1%) by method 1623. Infectious oocysts were detected in 22 of 560 samples (3.9%) by the CC-PCR technique. There was 87% agreement between the total numbers of samples positive as determined by method 1623 and CC-PCR for four of the sites. The other two sites had 16.3 and 24% correspondence between the methods. Infectious oocysts were detected in all of the watersheds. Overall, approximately 37% of the Cryptosporidium oocysts detected by the immunofluorescence method were viable and infectious. DNA sequence analysis of the Cryptosporidium parvum isolates detected by CC-PCR showed the presence of both the bovine and human genotypes. More than 90% of the C. parvum isolates were identified as having the bovine or bovine-like genotype. The estimates of the concentrations of infectious Cryptosporidium and the resulting daily and annual risks of infection compared well for the two methods. The results suggest that most surface water systems would require, on average, a 3-log reduction in source water Cryptosporidium levels to meet potable water goals.

The immunofluorescence assay (IFA), which is widely used for detection of Cryptosporidium in water samples, has been criticized as being time-consuming, labor-intensive, and expensive, and it requires a high degree of analytical expertise (1, 5, 11, 13). Moreover, the recovery efficiency of the procedure is low and variable, and it is subject to false-positive and -negative results. The antibodies used cross-react with species other than Cryptosporidium parvum (2), the causative agent of all waterborne cryptosporidiosis outbreaks (14). Importantly, the antibody-based microscopic methods do not provide information concerning the viability or infectivity of detected oocysts.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) has developed a refinement of the IFA, termed method 1622 for detection of Cryptosporidium or method 1623 for detection of Giardia and Cryptosporidium in water (32, 33). In these techniques a capsule filter and immunomagnetic separation (IMS) are used prior to analysis by immunofluorescence microscopy (4). Although the techniques generally have higher recovery efficiencies and greater precision, they still suffer from the limitations of an antibody-based method, principally the inability to assess the infectivity and public health significance of detected organisms (1, 6, 22).

Various cell culture lines have shown high levels of sensitivity to infection by low levels of Cryptosporidium oocysts (8, 21, 23, 24, 29). The human ileocecal adenocarcinoma HCT-18 cell line has the advantage of being a robust cell culture that is highly permissive to C. parvum infection (28-30). Detection of Cryptosporidium DNA by PCR has provided a high degree of specificity for detection of environmental oocysts (20, 35). The combination of cell culture and PCR (termed CC-PCR) provides the ability to specifically and accurately detect infectious Cryptosporidium in water samples (8, 9, 21). Di Giovanni et al. (8) used the CC-PCR method to examine 122 raw source water samples and 121 filter backwash samples and found infectious oocysts in 4.9 and 7.4% of the samples, respectively. Comparison of the detection rates for the CC-PCR and IFA methods (4.9 and 13.1%, respectively) suggested that, on average, 37% of the oocysts in the source waters examined were viable and infectious.

Although Cryptosporidium infection in cell culture can be detected by a variety of means, including enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and IFA techniques (23, 24, 36), there are advantages of using PCR. Analysis of PCR products can be used to confirm detection of Cryptosporidium oocysts and to determine the species and genotype of an isolate (8, 19, 25, 26, 35). In this regard, the hsp70 gene has proven to be useful as a reliable target for sequence analysis in order to determine genotypes of C. parvum and closely related species (27).

One objective of environmental monitoring is to estimate the risk of microbial exposure. Risk assessment requires accurate determinations of microbial occurrence, concentration, viability, and infectivity and human dose-response data. A meta-analysis of three human feeding studies by using the bovine genotype of C. parvum permitted estimation of the probability of infection by an unknown Cryptosporidium isolate (15). The purposes of this study were to collect data on Cryptosporidium occurrence, concentration, and infectivity from six different watersheds and to compare risk assessments by using the USEPA method 1623 and CC-PCR techniques. Determination of the risk of Cryptosporidium contamination in source water was used to estimate the degree of treatment required to meet public health goals for potable water supplies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Site selection.

The participating sites were chosen from a review of 20 watersheds to illustrate a range of watershed parameters. Consideration was given to the type of water body (whether the source water is a flowing stream, a reservoir, or a lake), the degree of vulnerability to pollution, and the variability (the expected frequency and amplitude of changes in water quality). Based on this evaluation, the following six locations were selected: Bull Run Reservoir; Allatoona Lake; Mianus River; the Mississippi River at Davenport, Iowa; Grand River; and the Tennessee River at Chattanooga, Tenn. The characteristics of these sites are shown in Table 1. Samples were collected at the intake of the participating water utility.

TABLE 1.

General watershed information for the selected sites

| Watershed | State or province | Source type | Principal source water | Watershed area (square miles) | Vulnerability | Point sourcesa | Nonpoint sources | Land use or land cover (%) | Soil type | % Impervious surfacef | Population | Precipi- tation (in./yr) | Slope (%) | Elevation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urbanb | Agricul- turalc | Range- landd | Forest | Othere | Water- shed | Served by water treatment plant | (ft) | m | ||||||||||||

| Bull Run Reservoir | Oregon | Reservoir | Bull Run River | 102 | Fully protected | No | Nof | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | Volcanic ash deposits, loess | 0 | None | 800,000 | 85.0 | <25 | 750-3,800 | 230-1,160 |

| Allatoona Lake | Georgia | Reservoir | Etowah River | 1,100 | Recreational, sewage, agricultural, combined sewer overflow | Yes, 2 upstream WWTPsg | Yes (cattle, hogs, chickens) | 8 | 15 | 4 | 73 | 0 | Sand and loam | 8 | 895,000 | 260,000 | 48.0 | <25 | 581-1,703 | 177-519 |

| Mianus River | Connecticut | River | Mianus River | 35 | Limited access, recreational, agricultural | No | Yes (ND)h | 29 | 2 | 0 | 69 | <1 | ND | 29 | 28,800 | 55,846 | 32.0 | 5-30 | 0 to 620 | 0-189 |

| Mississippi River at Davenport | Iowa | River | Mississippi River | 500 (study area) | Recreational, agricultural, sewage, combined sewer overflow, industrial | Yes, >10 upstream WWTPsi | Yes (cattle, hogs, corn, soybeans) | 25 | 56 | 0 | 14 | 5 | ND | 25 | ND | 135,000 | 36.0 | ND | 571 | 174 |

| Grand River at Kitchener, Ontario, Canada | Ontario | River | Grand River | 2,734 | Recreational, agricultural, sewage, industrial | Yes, 9 upstream WWTPsg | Yes (cattle, hogs, chickens, corn, small grlins, hay) | 7 | 78 | 0 | 14 | <2 | Sand and clay tills | 7 | 701,440 | 500,000 | 33.5-39.4 | 5-30 | 492-1,800 | 150-550 |

| Tennessee River at Chattanooga | Tennessee | River | Tennessee River | 1,875 (HUC area)j | Agricultural, sewage, combined sewer overflow, industrial | Yes, 3 to 5 upstream WWTPsi | Yes (cattle, wheat, soybean, corn) | 5 | 6 | 0 | 92 | 0 | Silt, silty clay loams, sandy loams | 5 | ND | 185,843 | 53.5 | 5-20 | 593-728 | 181-222 |

WWTP, wastewater treatment plant.

Urban or built-up land that is classified as residential, commercial, and industrial.

Agricultural land (crop and pasture).

Rangeland with grazing cattle.

Wetlands, barren land, and unimproved land.

Roads are not included.

Tertiary treatment.

ND, no data.

Secondary treatment.

HUC, hydrological unit catalog.

Water sample collection.

Approximately 100 samples were collected at each site. Samples were collected weekly, and additional samples were collected in series of daily or specific watershed event-based (typically rainfall-related) samplings. All source water samples were collected according to USEPA method 1623 (33) by using Gelman Envirochek filters (Pall-Gelman). At each site a minimum sample volume of 20 liters was collected (10 liters for direct IFA analyses and 10 liters for CC-PCR analyses), but at the Bull Run site, where the sample turbidity was particularly low, up to 100 liters was collected. All samples, regardless of the volume collected, were processed identically. Source water samples were collected through Gelman capsules at a flow rate of 2 liters per min and then transported on ice packs via overnight delivery to Clancy Environmental Consultants (CEC), Inc., for processing.

Method 1623.

Samples were processed as described in detail for method 1623 (33). Briefly, a 120-ml portion of Laureth-12 buffer was added to a capsule, and each filter was placed on a mechanical wrist action shaker (Labline model 3589; Fisher Scientific) and shaken with the inlet valve at the 12 o'clock position for 5 min. The eluate was transferred to a 250-ml conical centrifuge tube, and another 120 ml of elution buffer was added to the capsule, which was shaken again with the inlet valve at the 3 o'clock position for 5 min. The eluate from the second shaking step was pooled with the eluate generated from the first wash, the entire sample (approximately 250 ml) was centrifuged (1,050 × g, 10 min), and the supernatant was aspirated to 10 ml and subjected to IMS. When the pellet volume was greater than 1 ml, a packed pellet volume equivalent to 1 ml was resuspended in 10 ml.

The Dynal IMS procedure (Dynabeads G/C combo IMS kit; Dynal A.S., Oslo, Norway) was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions, with a few exceptions. Briefly, each 10-ml portion of a test sample was placed in a screw-cap Leighton tube, and 1 ml of 10× SL buffer A, 1 ml of 10× SL buffer B, 100 μl of the anti-Cryptosporidium bead conjugate, and 100 μl of an anti-Giardia bead conjugate were added. Each sample was allowed to rotate through 360o for 1 h (at room temperature), and the Leighton tube was placed in a magnetic particle concentrator 1 to separate the bead-oocyst complex from the contaminating debris. The beads were resuspended in 1 ml of 1× SL buffer A, transferred into an Eppendorf tube, and separated by using a magnetic particle concentrator M, and the supernatant was removed and discarded. The beads were resuspended in 200 μl of Hanks buffered saline solution (HBSS) with bromophenol blue (0.001%), and 50% of the sample (100 μl) was shipped to the Belleville Laboratory of American Water Works Service Company, Inc., for CC-PCR analysis. The remaining 100 μl of the sample, representing one-half of the original sample volume (i.e., 10 liters), was subjected to dissociation with 0.1 N HCl, and the neutralization procedure was performed on a microscope slide by using 10 μl of 1 N NaOH. Each sample concentrate was placed in an individual well of a three-well microscope slide, dried (42°C), labeled with anti-Cryptosporidium fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) monoclonal antibody (MAb)-anti-Giardia FITC MAb (Waterborne Inc., New Orleans, La.), and examined by epifluorescence microscopy.

Zeiss Axioskop fluorescence microscopes (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging Inc., Thornwood, N.Y.) equipped with blue filter block (excitation wavelength, 490 nm; emission wavelength, 510 nm) were used for detection of FITC MAb-labeled oocysts or cysts at a magnification of ×200. Confirmation of oocysts of cysts was achieved at a magnification of ×400 by using a UV filter block (excitation wavelength, 400 nm; emission wavelength, 420 nm) for visualization of 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), and the internal morphology of oocysts or cysts was observed by using Nomarski differential interference-contrast microscopy.

CC-PCR method.

Human ileocecal adenocarcinoma HCT-18 (ATCC CCL-1244) cells were cultivated as previously described (36). The cell culture maintenance medium consisted of RPMI 1640 supplemented with l-glutamine (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.), 5% fetal bovine serum (pH 7.2), 15 mM HEPES buffer, 100,000 U of penicillin G per liter, 100 mg of streptomycin per liter, 700 μg of amphotericin B per liter, and 12.5 mg of tetracycline per liter. The growth medium used for in vitro development of C. parvum contained 10% fetal bovine serum, 15 mM HEPES buffer, 50 mM glucose, 35 mg of ascorbic acid per liter, 1.0 mg of folic acid per liter, 4.0 mg of 4-aminobenzoic acid per liter, 2.0 mg of calcium pantothenate per liter, 100,000 U of penicillin G per liter, 100 mg of streptomycin per liter, 700 μg of amphotericin B per liter, and 12.5 mg of tetracycline per liter. Twenty-four hours prior to inoculation, 96-well cell culture microplates were seeded with 5 × 104 HCT-18 cells per well. The plates were then incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator to allow the development of 100% confluent monolayers.

Splits of IMS-purified (up to the dissociation step) water samples received from CEC were prepared for cell culture by adding 98 μl of HBSS containing 2% trypsin and 2.0 μl of 1 M HCl (designated acidified HBSS). Samples were then incubated at 37°C for 1 h with 10 s of vortexing every 15 min. Following separation of the samples with the magnetic particle concentrator, the supernatants containing the dissociated oocysts were transferred to Microfuge tubes. To ensure recovery of oocysts, a second wash of the IMS beads with 100 μl of acidified HBSS-1% trypsin was performed. Pooled dissociated samples were neutralized with 0.5 N NaOH (approximately 4.0 μl) and centrifuged at the maximum speed in a microcentrifuge for 2 min with no brake and aspirated down to 20 μl for CC-PCR. Just prior to inoculation of monolayers, 50 μl of maintenance medium was removed. Samples for CC-PCR were resuspended in 80 μl of prewarmed growth medium immediately following IMS dissociation and were used to inoculate an HCT-18 cell monolayer. Monolayers were inoculated and then incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator for 72 h prior to DNA extraction. Acidified HBSS-1% trypsin-treated viable C. parvum oocysts were used as CC-PCR positive controls (approximately 5 to 20 oocysts per cell monolayer, depending on the infectivity of the oocyst stock), and oocysts killed with a single freeze-thaw cycle were used as CC-PCR negative controls. After incubation, the cell monolayers were washed five times with 200 μl of phosphate-buffered saline to remove unexcysted oocysts.

DNA was purified from HCT-8 cells by using a QIAamp DNA mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.) and a modified extraction protocol. The modifications included incubation of the cell monolayers with lysis buffer for 15 min at 70 to 75°C and elution of DNA from the QIAamp DNA columns with 50 μl of 0.1× Tris-EDTA buffer (pH 8.0) at 70 to 75°C for 5 min. Oocyst DNA was prepared by using a rapid and simple freeze-thaw extraction procedure. Chelex 100 resin (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) was prepared as an equilibrated 1:1 (vol/vol) mixture of resin and 1× Tris-EDTA buffer (pH 8.0). For each sample an equal volume of prepared Chelex resin was added. Oocysts were lysed by eight cycles (1 min each) consisting of freezing in liquid nitrogen and thawing at 98°C.

PCR primers specific for the C. parvum hsp70 gene were used, which resulted in a 346-bp product. The primer sequences were as follows: forward primer CPHSPT2F, 5′ TCCTCTGCCGTACAGGATCTCTTA 3′; and reverse primer CPHSPT2R, 5′ TGCTGCTCTTACCAGTACTCTTATCA 3′. PCR was performed with a Perkin-Elmer model 9600 thermal cycler (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). The 100-μl PCR mixtures contained 10.0 μl of 10× amplification buffer with Mg (final concentration,1.5 mM; Roche Molecular, Branchburg, N.J.); 200 μM dATP, 200 μM dTTP, 200 μM dCTP, and 200 μM dGTP (al obtained from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.); 200 nM forward primer CPHSP2; 200 nM reverse primer CPHSP2; 2.5 μl of a 30-mg ml−1 solution of bovine serum albumin (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.); 5.0 U of AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase (Roche Molecular); and various amounts of C. parvum template DNA (up to 50 μl). Aliquots (up to 10% of the final PCR volume) of Chelex 100 freeze-thaw-prepared oocyst DNA equivalent to approximately 10 oocysts were used as PCR positive controls, and molecular grade water was used to prepare nontemplate negative PCR controls. The amplification conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min; 45 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s and annealing at 60°C for 1 min; and then a final extension at 72°C for 10 min and a 4°C hold. Amplification products were separated by horizontal gel electrophoresis on a 2.0% agarose gel (Amresco, Solon, Ohio) containing 0.5 μg of ethidium bromide (Sigma Chemical Co.) per ml and were visualized under UV light. Gel images were captured by using a gel documentation system (UVP, Inc., Upland, Calif.).

Quality assurance.

Additional quality control matrix samples for the purpose of spike recovery analysis were collected by the participating utilities. Replicate samples were sent to CEC, where a known number of C. parvum oocysts (approximately 500) were spiked directly by using the inlet port. These spiked samples were eluted from the capsule filters by method 1623 as previously described.

The Iowa isolate of C. parvum oocysts, originally obtained from Harley Moon (National Animal Disease Center, Ames, Iowa), was maintained at the Sterling Parasitology Laboratory (University of Arizona, Tucson) and used for evaluation of method performance for various source water matrices. Stock oocysts were received in deionized water containing 0.01% Tween 20 and an antibiotic solution (100 U of penicillin per ml and 100 μg of gentamicin per ml). Working suspensions were prepared and stored at 4°C in deionized water with no additional antibiotics added. The oocysts were less than 1 month old.

QSD.

Because the CC-PCR technique used in this study gave a presence-or-absence result, quantitative cell culture PCR with cell culture quantitative sequence detection (CC-QSD) and a PE Applied Biosystems 7700 sequence detector (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.) was performed to determine the cell culture recovery efficiency (7). The primers used were the same as those described above, and the CPHSP2P2 TaqMan probe sequence was as follows: 5′ TGTTGCTCCATTATCACTCGGTTTAGA 3′. Each 100-μl CC-QSD mixture contained 10.0 μl of 10× TaqMan A amplification buffer (Roche Molecular); 1.5 mM MgCl2; 200 μM dATP, 200 μM dTTP, 200 μM dCTP, and 200 μM dGTP (all obtained from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech); 200 nM forward and 200 nM reverse CPHSPT2 primer and CPHSP2P2 TaqMan probes (Synthegen, Houston, Tex.); 5.0 μl of a 30-mg ml−1 solution of bovine serum albumin (Sigma Chemical Co.); and 5.0 U of AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase (Roche Molecular). Purified cell culture DNA for each sample (50 μl) or aliquots of Chelex-treated oocyst DNA controls (up to 10 μl) were used as templates. Human β-actin gene DNA and appropriate primers and probes (Roche Molecular) were used as amplification standards. Molecular grade water was used to prepare no-template negative controls. The amplification conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min; 45 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s and annealing at 60°C for 1 min; and then a final extension at 72°C for 10 min and a 4°C hold.

Genotyping of C. parvum isolates.

CC-PCR products were cloned and sequenced to confirm homology to the C. parvum hsp70 gene. Products were cloned by using a TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cloned products were sequenced commercially (ACGT, Northbrook, Ill., and DNA Sequencing Service, University of Arizona, Tucson), and sequence homology to the C. parvum KSU-1 hsp70 gene (12) was confirmed by using Gene Runner, version 3.0 (Hastings Software, Inc., Hastings, N.Y.), or GeneBase, version 1 (Applied Maths, Kortrijk, Belgium). Sequences were aligned, and similarity dendrograms were generated by using the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic averages and GeneBase. Duplicate clones of each PCR product were sequenced and analyzed to identify potential sequencing errors. When possible, clones obtained from independent CC-PCR analyses of the same sample were analyzed to exclude random nucleotide misincorporation by Taq DNA polymerase.

Risk assessment.

To estimate the risk of infection from Cryptosporidium in source water, the mean infectious dose data of Messner et al. (15) were used. A value of 0.028 was used for the probability of infection from a single oocyst for an unknown strain. The daily and annual risks of infection were calculated as follows: daily risk = (1.2 liters/day)(oocysts/liter)(infection probability for unknown strain); annual risk = 1 − (1 − daily risk)350.

For method 1623 data, the average source water oocyst concentration for each site was adjusted for the average method recovery efficiency and an overall 37% infectivity factor. For the CC-PCR method, it was assumed that each positive CC-PCR sample was the result of a single infectious oocyst. The infectious oocyst concentration was determined by dividing the number of positive samples by the total equivalent volume analyzed (in liters) and adjusting the value for the average method recovery efficiency.

Statistical analysis.

All project data were coded by using a common coding system and were entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. All spreadsheets were reviewed for quality control and loaded into a Microsoft Access database. Data were transferred to SAS (Statistical Analysis System; SAS Institute Inc.) for further analyses. The statistical analyses included a t test, a test of normality, and logistic regression. Best-fit distribution and Monte Carlo simulations were performed by using Crystal Ball, version 4.0 (DECISIONEERING, Boulder, Colo.).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Spiked sample recovery.

To measure the efficiency of protozoan detection, 29 environmental samples were collected at the six sites and spiked at the CEC laboratory. The spiked samples were processed to the IMS stage, and splits were sent to American Water Works Service Company, Inc., where CC-QSD was performed on nine samples. The recovery efficiencies obtained in both laboratories are shown in Table 2. Two samples were not analyzed by CC-QSD due to failed PCRs. The average recovery efficiency ± standard deviation for Cryptosporidium when method 1623 was used was 72% ± 22%. The recovery efficiency of the CC-QSD method was 58.5% ± 13%. The recovery efficiencies were normally distributed. The Cryptosporidium recovery data from the CC-QSD method and method 1623 were not statistically different at the 95% confidence level (P = 0.06).

TABLE 2.

Recovery efficiencies for Cryptosporidium by method 1623 and CC-PCR (with QSD)

| Sample site | Sample |

Cryptosporidium recovery (%)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Method 1623 | CC-PCR with QSD | ||

| Mianus River, Connecticut | CT19399SP | 46.80 | |

| CT23599SP | 69.50 | ||

| CT34299SP | 71.00 | ||

| CT05500SP | 47.20 | 69.53 | |

| CT12200SP | 97.70 | 52.30 | |

| Allatoona Lake, Georgia | GA20099SP | 57.20 | |

| GA27299SP | 77.20 | ||

| GA29899SP | 57.80 | ||

| GA02400SP | 76.70 | ||

| GA13600SP | 38.60 | 37.30 | |

| Mississippi River, Iowa | IA16599SP | 110.20 | |

| IA28599SP | 93.50 | ||

| IA33399SP | 57.20 | ||

| IA04500SP | 106.90 | 62.57 | |

| Grand River, Ontario | ON16599SP | 59.90 | |

| ON25699SP | 85.70 | ||

| ON29899SP | 85.90 | ||

| ON04000SP | 83.00 | 56.08 | |

| ON08000SP | 89.80 | 79.00 | |

| Bull Run Reservoir, Oregon | OR17399SP | 64.30 | |

| OR22899SP | 57.70 | ||

| OR30599SP | 66.80 | ||

| OR05900SP | 87.40 | NRa | |

| OR10800SP | 92.50 | NR | |

| Tennessee River, Tennessee | TN21099SP | 88.20 | |

| TN27799SP | 5.90 | ||

| TN31299SP | 82.60 | ||

| TN01000SP | 67.30 | ||

| TN11500SP | 68.00 | 52.80 | |

NR, no result. The sample was lost due to failed PCR.

Occurrence of Cryptosporidium in the watersheds.

Method 1623 detects all Cryptosporidium oocysts, both viable and nonviable. Overall, Cryptosporidium oocysts were detected in 60 of 593 (10.1%) of the samples by method 1623. In the watersheds studied, the fractions of samples with detectable oocysts ranged from 0 to 36% (Table 3). The average concentrations of Cryptosporidium ranged from <0.001 to 0.069 oocyst/liter (Table 4). During peak events, the levels of Cryptosporidium could exceed 1.0 oocyst/liter.

TABLE 3.

Cryptosporidium results for method 1623 and CC-PCR by site

| Method | Site | No. of samples | No. of samples in which Cryptosporidium was detected | No. of samples in which Cryptosporidium concn was below the detection limit | No. of samples positive | No. of samples negative |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1623a | Georgia | 98 | 0 | 98 | ||

| Iowa | 101 | 7 | 94 | |||

| Connecticut | 98 | 7 | 91 | |||

| Ontario | 98 | 33 | 65 | |||

| Tennessee | 101 | 4 | 97 | |||

| Oregon | 97 | 9 | 88 | |||

| CC-PCRb | Georgia | 94 | 1 | 93 | ||

| Iowa | 96 | 4 | 92 | |||

| Connecticut | 91 | 5 | 86 | |||

| Ontario | 91 | 5 | 86 | |||

| Tennessee | 99 | 5 | 94 | |||

| Oregon | 89 | 2 | 87 |

A total of 593 samples were analyzed. Cryptosporidium was detected in 60 of these samples, and the Crytosporidium concentration was below the detection limit in 533 of them. Two nonevent samples were not received by the laboratory.

A total of 560 samples were analyzed. Twenty-two of these samples were positive, and 538 of them were negative. Four samples were not received by the laboratory, and 31 samples were lost due to cytotoxicity (14 samples) or failed PCR (17 samples).

TABLE 4.

Concentrations of Cryptosporidium based on method 1623

| Watershed | No. of samples |

Cryptosporidium concn (oocysts/liter)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Avg | Range | ||

| Oregon | 97 | 0.004 | 0.0-0.08 |

| Georgia | 98 | <0.001 | |

| Connecticut | 98 | 0.012 | 0.0-0.50 |

| Iowa | 101 | 0.017 | 0.0-1.17 |

| Tennessee | 101 | 0.005 | 0.0-0.20 |

| Ontario | 98 | 0.069 | 0.0-1.00 |

The CC-PCR technique detects infectious C. parvum in a water sample. Of 560 samples tested, 22 (3.9%) were positive for Cryptosporidium as determined by the CC-PCR technique (Table 3). Thirty-one samples were not analyzed due to cytotoxicity from excessive carryover of trypsin during sample processing (14 samples) or failed PCRs (17 samples), and four samples were lost during shipping. Infectious oocysts were detected in all of the watersheds tested.

For four of the sites (those in Georgia, Tennessee, Iowa, and Connecticut) there was 87% correspondence between the total number of samples positive as determined by method 1623 and the total number of samples positive as determined by CC-PCR. For these four sites, oocysts were detected in 18 of 398 samples (4.52%) by using method 1623, compared to 15 positive results for 380 samples (3.95%) when the CC-PCR technique was used (0.0395/0.0452 × 100 = 87%). These results suggest that for some sites the majority of the oocysts detected may be viable and infectious.

Although the Grand River site (in Ontario, Canada) had the highest frequency of detection of oocysts (33.7%) when method 1623 was used, only 5.5% of the samples were positive as determined by CC-PCR. Oocysts were detected in 33 of 98 samples when method 1623 was used but in only 5 of 91 samples when the CC-PCR technique was used (0.0549/0.3367 × 100 = 16.3%). Similarly, for the pristine Oregon site we detected oocysts in 9 of 97 samples by method 1623 but in only 2 of 89 samples by CC-PCR, resulting in a 24% viability rate. The discrepancy between the immunofluorescence and cell culture techniques may be due to the detection of cross-reacting objects, nonviable isolates, or Cryptosporidium species that cannot infect HCT-8 cells or be detected with the CPHSPT2 primer set.

Seasonal distribution.

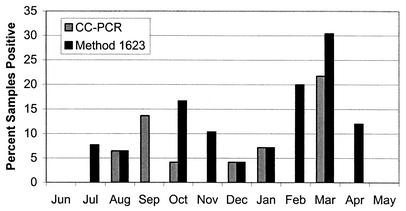

The seasonal distribution of method 1623 and CC-PCR results showed a biphasic pattern, with an increase in the frequency of oocyst detection in the fall and in the spring (Fig. 1). For this analysis, only paired weekly data were used in order to avoid any seasonal bias from the daily or event-based sampling program. The increase in March is notable; 30.4% of the 23 samples analyzed by method 1623 and 21.7% of the samples tested by CC-PCR were positive. During March, for all sites except the Georgia and Oregon sites there were samples that were positive as determined by the CC-PCR method, indicating that the infectious oocysts were distributed across multiple watersheds. Oocysts were detected in three of the watersheds (Tennessee, Ontario, and Iowa) by method 1623 during March. Other workers have observed similar seasonal distributions, in which protozoans were detected predominantly during the colder months of the year (3, 17, 18).

FIG. 1.

Seasonal distribution of Cryptosporidium oocysts as determined by method 1623 and CC-PCR. Only paired weekly data for method 1623 and CC-PCR are shown (n = 295).

Cryptosporidium infectivity.

Overall, 60 samples were positive as determined by method 1623 and 22 samples were positive as determined by CC-PCR (Table 3), suggesting that 37% of the detected Cryptosporidium oocysts were alive and infectious. In a previous study of 122 source water samples from 25 sites Di Giovanni et al. (8) detected Cryptosporidium in 16 (13.1%) of the samples when IFA was used and 6 (4.9%) of the samples when CC-PCR was used, resulting in a similar infectivity estimate (37%).

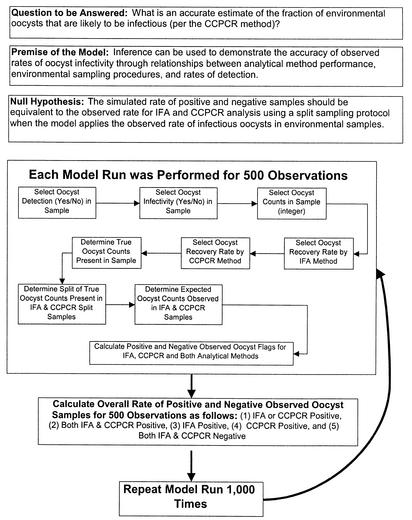

However, when we considered the entire population of samples analyzed by both CC-PCR and method 1623 (IFA), only 1 of 560 samples (0.2%) was positive as determined by both methods of analysis (Table 5). This very low probability of joint positive results appeared to bring into question our ability to compare the methods to determine Cryptosporidium infectivity. To test this conclusion, a Monte Carlo simulation model was developed by using the observed distributions of positive samples as determined by method 1623 and CC-PCR, the numbers of oocysts counted in environmental samples, and the recovery efficiencies for methods 1623 and CC-PCR (Table 6). The algorithm used in the Monte Carlo simulation involved a several-step process in which the defined distributions were sampled and used to calculate the likelihood that both method 1623 and CC-PCR would produce positive results (Fig. 2).

TABLE 5.

Comparative contingency table for Cryptosporidium detection methods

| IFA (method 1623) results | No. of samples with the following CC-PCR results:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | No result | Total | |

| Positive | 1 | 55 | 4 | 60 |

| Negative | 21 | 483 | 29 | 533 |

| No result | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Total | 22 | 538 | 35 | 595 |

TABLE 6.

Observations and assumptions for the Monte Carlo simulation model design

| No. | Observation or assumption used in the Monte Carlo simulation model |

|---|---|

| 1 | Cryptosporidium oocysts were detected in 10% of all environmental samples for this study by method 1623 (IFA). |

| 2 | 4% of all samples collected and analyzed by CC-PCR tested positive (infectious). This result implies that 40% (0.04/0.10 × 100) of all samples with detectable oocysts also have infectious oocysts present. |

| 3 | The recovery rate for Cryptosporidium by method 1623 (IFA) for this study was found to have the following best-fit distribution: Weibull (location, −197.38; scale, 279.16; shape, 15.00). The best-fit recovery rate for CC-PCR was found to be logistic (mean, 58.38; scale, 7.46). |

| 4 | For this study, the oocyst counts in environmental samples in which oocysts were detected had the following probability density: 5 = 3%, 4 = 5%, 3 = 8%, 2 = 17%, and 1 = 67%. |

| 5 | A binomial distribution was used to estimate the number of oocysts that would be split between the sample analyzed by method 1623 (IFA method) and the sample analyzed by CC-PCR. |

FIG. 2.

Algorithm used for the Monte Carlo simulation model to test the likelihood that the observed rates of oocyst detection and infectivity reasonably represent an accurate assessment of occurrence in environmental samples. Table 6 shows the assumptions used in this model.

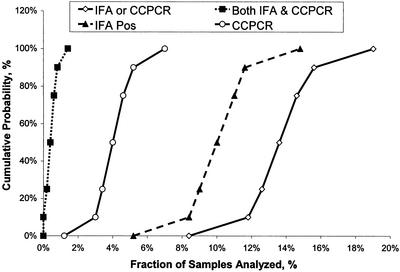

With the simulation model we used inference to test whether the observed results for the levels of Cryptosporidium detection and infectivity were reasonable. Since the observed rates for detection and infectivity were input into the model, the unknown parameter estimated was the joint probability of having both methods result in a positive outcome. The median probabilities of Cryptosporidium detection by either method 1623 (IFA) or CC-PCR ranged from 8 to 19% (Fig. 3). However, the probabilities of obtaining positive results with both methods ranged from 0 to 1.4%, and the median value was 0.4%. This result agreed well with the observed rate of 0.2% for the environmental samples collected in this study.

FIG. 3.

Predicted probability distribution of oocyst detection and infectivity levels when the Monte Carlo simulation model described in Fig. 2 was used. IFA, detection of oocysts by method 1623; CCPCR, infectivity results obtained by CC-PCR. Pos, positive.

This study highlights the limitations of using environmental samples to compare Cryptosporidium analytical techniques. The low frequency of occurrence, low oocyst concentrations, low recovery efficiencies (<90%), and errors in splitting samples all result in few samples with simultaneous detections. This results in problems with efforts to compare developing methods using realistic environmental samples. Options that include spiked samples or animal feces or sewage samples may limit the diversity of Cryptosporidium present. Understanding the specificities of the various analytical techniques, particularly method 1623, would greatly benefit the development of method comparison protocols.

Analysis of DNA sequences.

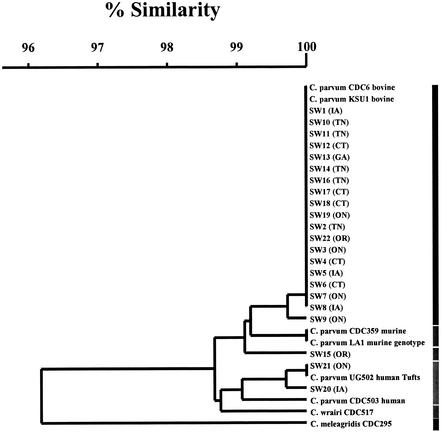

DNA sequence analysis of the 22 CC-PCR C. parvum isolates allowed identification of both bovine and human genotypes (Fig. 4). Similar to the results of a previous study in which the CC-PCR method was used (8), the C. parvum bovine genotype was the most commonly detected genotype. Two novel C. parvum hsp70 genotypes were detected, represented by single isolates, SW9 and SW15. SW9 was similar to the C. parvum bovine genotype, differing at only one nucleotide position.

FIG. 4.

Similarity dendrogram for CC-PCR C. parvum hsp70 genotypes obtained from this study and reference sequences from the Centers for Disease Control and C. parvum isolates. The origins are indicated in parentheses, as follows: CT, Connecticut; IA, Iowa; TN, Tennessee; GA, Georgia; OR, Oregon; and ON, Ontario, Canada.

Isolate SW15 was obtained from a sample collected at the Oregon site, which is fully protected from human impact. This isolate was different from the C. parvum bovine genotype at three nucleotide positions but clustered with the bovine and murine genotypes (Fig. 4). It is possible that this isolate represents a new genotype of C. parvum from a wild animal host. Another isolate (isolate SW22) was obtained from the Oregon site and was identified as the C. parvum bovine genotype.

Cryptosporidium meleagridis and Cryptosporidium wrairi, the two species of Cryptosporidium most closely related to C. parvum, were included in the analysis, and all CC-PCR isolates were found to cluster more closely with C. parvum. C. wrairi and C. meleagridis are amplified by the CPHSPT2 primer set (10), but it is not known if they can be propagated in the HCT-8 cell line. Five C. parvum (sub)genotypes were detected, including the bovine and human genotypes and one bovine-like genotype. The C. parvum bovine and bovine-like genotypes were found in 20 (90.9%) of the 22 isolates. This finding is not surprising since the bovine genotype is capable of infecting many mammals, including humans, livestock (especially calves), and wild animals.

The C. parvum human genotype was found in 2 (9.1%) of the 22 isolates. Until recently, this genotype was thought to be capable of infecting only humans. However, the C. parvum human genotype was recently found in an Australian dugong (an animal similar to a manatee) (16). The study showed that the animal was living in a body of water affected by a wastewater treatment plant. The C. parvum human genotype can be further divided into subgenotypes based on the hsp70 gene (27). Two different C. parvum human subgenotypes were detected in the present study, represented by SW21 and SW20. SW21 was found to be identical to two C. parvum human genotype clinical isolates obtained from colleagues at Murdoch University in Australia and Tufts University in Massachusetts. The SW21 genotype matched the genotype of an isolate recovered in a previous project in which filter backwash water was examined (8). Therefore, this C. parvum human subgenotype appears to be geographically diverse. It is not possible at this point to determine the significance of the distribution of C. parvum genotypes, but this information may be useful in the future to better understand the ecology and evolution of the organism in various watersheds.

Risk assessment.

To perform a risk assessment with CC-PCR data, it was assumed that each positive CC-PCR sample was the result of a single infectious oocyst. This assumption is supported by the low frequency of occurrence of Cryptosporidium in this study and the frequent detection of a single oocyst by microscopic evaluation (40 of 60 positive samples were due to a single oocyst). Data for method 1623 were adjusted by a 37% infectivity factor. Source water oocyst concentrations were adjusted for the method recovery efficiency (0.72 for method 1623 and 0.585 for the CC-PCR technique). Overall, the estimated concentrations of infectious Cryptosporidium and the resulting daily and annual risks of infection for consumption of untreated surface water were within a factor of 3 for the two methods for the various watersheds (Table 7). Given that the 80% credible interval for the risk of infection from a single oocyst is quite large (0.005 to 0.066) (15), the two methods estimate essentially the same risk.

TABLE 7.

Estimated risks of infection after consumption of untreated surface water

| Site | Estimated concn (no. of infectious oocysts/liter)

|

Daily risk of infection

|

Annual risk of infection (1/yr)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC-PCRa | Method 1623b | CC-PCR | Method 1623 | CC-PCR | Method 1623 | |

| Ontario | 0.0112 | 0.0355 | 0.00038 | 0.00119 | 8.1 | 2.9 |

| Connecticut | 0.0095 | 0.0062 | 0.00032 | 0.00021 | 9.5 | 14.3 |

| Tennessee | 0.0089 | 0.0026 | 0.00030 | 0.00009 | 10.1 | 33.6 |

| Iowa | 0.0084 | 0.0087 | 0.00028 | 0.00029 | 10.6 | 10.2 |

| Georgia | 0.0018 | <0.0005 | 0.00006 | <0.00002 | 47.9 | >166 |

| Oregon | 0.0009 | 0.0021 | 0.00003 | 0.00007 | 94.5 | 41.9 |

It was assumed that a positive CC-PCR sample resulted from a single infectious oocyst, adjusted for the averaged recovery efficiency (0.585).

Concentrations were adjusted for recovery efficiency (0.72) and for an overall 37% infectivity factor.

The USEPA has established an annual risk of infection of 1/10,000 as a reasonable goal for drinking water supplies (31). When the risk assessments for the watersheds examined in this study were compared, most systems would require, on average, an additional 1,000-fold (3-log) reduction in source water Cryptosporidium levels to meet potable water goals. During the spring months, treatment plants need to apply an additional 3.2-log treatment (data not shown). One of the watersheds examined is a pristine unfiltered system, and risk estimates for this supply suggest that an additional 2 to 2.5 logs of treatment is required. It should be noted that there are wide variations in infectious dose data (15), and additional dose-response data are needed for a variety of environmental isolates before more refined estimates of risk can be determined.

The practical application for water utilities is to assume that all source waters are potential risks for transmission of cryptosporidiosis, even if the occurrence and frequency of oocyst detection are low. At first, this conclusion may be thought to be at odds with the Long-Term II Enhanced Surface Water Treatment Rule that will require systems with high average source water Cryptosporidium levels (0.075 oocyst/liter) to provide additional levels of treatment beyond conventional filtration (34). In this study we did not discount the possibility that systems with high levels of source water contamination may benefit from advanced levels of treatment. However, systems with source water Cryptosporidium levels below the threshold limits of the LT2ESWTR should recognize that infectious oocysts are present in their watersheds and that they should always strive for the greatest level of treatment possible. In this study infectious oocysts were detected in all of the watersheds despite the fact that the average concentrations were below the LT2ESWTR threshold level.

Conclusions.

This study showed that there was good agreement between Cryptosporidium occurrence levels in six watersheds when method 1623 and the CC-PCR technique were used. The detection of infectious oocysts in all watersheds, including a very pristine site, demonstrates the important public health concerns with this organism. The 87% agreement between the total numbers of samples positive as determined by method 1623 and CC-PCR for a number of the sites suggests that an assumption that there is health risk based on immunofluorescence results may be reasonable for many locations. Estimates of the concentrations of infectious Cryptosporidium and the resulting daily and annual risks of infection compared well for the two methods. The results suggest that most systems would require, on average, a 3-log reduction in source water Cryptosporidium levels to meet potable water goals. Our evidence supports other research and epidemiological evidence that shows that the greatest risk for waterborne cryptosporidiosis is in the spring. The predominant detection of bovine or bovine-like C. parvum genotypes suggests that greater emphasis should be placed on understanding the human health significance of the organisms in water.

Acknowledgments

We thank Frank Blaha, project manager for the American Water Works Association Research Foundation, Denver, Colo., and the following members of the Project Advisory Committee for their guidance and suggestions: Khalil Atasi, Tetra Tech Engineers, Detroit, Mich.; Christopher Crocket, Philadelphia Water Department, Philadelphia, Pa.; Stephen Schaub, USEPA, Washington, D.C.; Helena Solo Gabriele, University of Miami, Coral Gables, Fla.; Melinda Rho, City of Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, Los Angeles, Calif.; Mark Knudson, Portland Water Bureau, Portland, Oreg.; and Mike Messner, USEPA, Washington, D.C. We thank Andrew Thompson and Giovanni Widmer for providing C. parvum human genotype oocysts. We also thank the participating utilities for their outstanding contributions and commitment to the project.

This project was funded by the American Water Works Association Research Foundation, the USEPA, and the utility subsidiaries of the American Water System, Voorhees, N.J.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen, M. J., J. L. Clancy, and E. W. Rice. 2000. The plain hard truth about pathogen monitoring. J. Am. Water Works Assoc. 92(9): 64-76. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arrowood, M. J. 1997. Diagnosis, p. 43-64. In R. Fayer (ed.), Cryptosporidium and cryptosporidiosis. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Fla.

- 3.Atherholt, T. B., M. W. LeChevallier, W. D. Norton, and J. S. Rosen. 1998. Effect of rainfall on Giardia and Crypto. J. Am. Water Works Assoc. 90(9):66-80. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clancy, J. L., Z. Bukhari, R. M. McCuin, Z. Matheson, and C. Fricker. 1999. USEPA method 1622. J. Am. Water Works Assoc. 91(9):60-68. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clancy, J. L., W. D. Gollnitz, and Z. Tabib. 1994. Commercial labs: how accurate are they? J. Am. Water Works Assoc. 86(5):89-97. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Connell, K., C. C. Rogers, H. L. Shank-Givens, J. Scheller, M. L. Pope, and K. Miller. 2000. Building a better protozoan data set. J. Am. Water Works Assoc. 92(10):20-43. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di Giovanni, G., M. Denhart, M. LeChevallier, and M. Abbaszadegan. 1999. Quantitation of intact and infectious Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts using quantitative sequence detection (QSD), p. 1-5. In Proceedings of the AWWA Water Quality Technology Conference. American Water Works Association, Denver, Colo. [On CD-ROM.]

- 8.Di Giovanni, G. D., F. H. Hashemi, N. J. Shaw, F. A. Abrams, M. W. LeChevallier, and M. Abbaszadegan. 1999. Detection of infectious Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts in surface and filter backwash water samples by immunomagnetic separation and integrated cell culture PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:3427-3432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di Giovanni, G. D., and M. W. LeChevallier. 2000. Development of a Cryptosporidium parvum viability and infectivity assay. A report to the American Water Works Service Company, Inc. American Water Works Service Company, Inc., Voorhees, N.J.

- 10.Di Giovanni, G. D., M. R. Karim, M. W. LeChevallier, J. R. Weihe, F. A. Abrams, M. L. Spinner, S. N. Boutros, and J. S. Chandler. 2002. Overcoming molecular sample processing limitations: quantitative PCR. Publication 00-HHE-2b. Water Environment Research Foundation, Alexandria, Va.

- 11.Jakubowski, W., S. Boutros, W. Faber, R. Fayer, W. Ghiorse, M. LeChevallier, J. Rose, S. Schaub, A. Singh, and M. Stewart. 1996. Environmental methods for Cryptosporidium. J. Am. Water Works Assoc. 87(9):107-121. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khramtsov, N. V., M. Tilley, D. S. Blunt, B. A. Montelone, and S. J. Upton. 1995. Cloning and analysis of a Cryptosporidium parvum gene encoding a protein with homology to cytoplasmic form Hsp70. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 42:416-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.LeChevallier, M. W., W. D. Norton, J. E. Siegel, and M. Abbaszadegan. 1995. Evaluation of the immunofluorescence procedure for detection of Giardia and Cryptosporidium in water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:690-697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McLauchlin, J., C. Amar, S. Pedraza-Diaz, and G. L. Nichols. 2000. Molecular epidemiological analysis of Cryptosporidium spp. in the United Kingdom: results of genotyping Cryptosporidium spp. in 1,705 fecal samples from humans and 105 fecal samples from livestock animals. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3984-3990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Messner, M. J., C. Chappell, and P. C. Okhuysen. 2001. Risk assessment for Cryptosporidium: a hierarchical Bayesian analysis of human dose response data. Water Res. 35:3934-3940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morgan, U. M., L. Xiao, D. B. Hill, P. O'Donoghue, J. Limor, A. Lal, and R. C. Thompson. 2000. Detection of the Cryptosporidium parvum “human” genotype in a dugong (Dugong dugon). J. Parasitol. 86:1352-1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ong, C. S. L., W. P. Morrehead, A. Ross, and J. L. Isaac-Renton. 1996. Studies of Giardia spp. and Cryptosporidium spp. in two adjacent watersheds. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:2798-2805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Payment, P., A. Berte, M. Prevost, B. Menard, and B. Barbeau. 2000. Occurrence of pathogenic microorganisms in the Saint Lawrence River (Canada) and comparison of health risks for populations using it as their source of drinking water. Can. J. Microbiol. 46:565-576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peng, M. M., L. Xiao, A. R. Freeman, M. J. Arrowood, A. A. Escalante, A. C. Weltman, C. S. L. Ong, W. R. MacKenzie, A. A. Lal, and C. B. Beard. 1997. Genetic polymorphism among Cryptosporidium parvum isolates: evidence of two distinct human transmission cycles. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 3:567-573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rochelle, P. A., R. De Leon, M. H. Stewart, and R. L. Wolfe. 1997. Comparison of primers and optimization of PCR for detection of Cryptosporidium and Giardia in water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:106-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rochelle, P. A., D. M. Ferguson, T. J. Handojo, R. De Leon, M. H. Stewart, and R. L. Wolfe. 1997. An assay combining cell culture with reverse transcriptase PCR to detect and determine infectivity of waterborne Cryptosporidium parvum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:2029-2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simmons, O. D., M. D. Sobsey, C. D. Heaney, F. W. Schaefer, and D. S. Francy. 2001. Concentration and detection of Cryptosporidium oocysts in surface water samples by method 1622 using ultrafiltration and capsule filtration. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:1123-1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Slifko, T. R., D. E. Friedman, and J. B. Rose. 1999. A most-probable-number assay for the enumeration of infectious Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:3936-3941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Slifko, T. R., D. E. Friedman, J. B. Rose, S. J. Upton, and W. Jakubowski. 1997. An in vitro method for detection of infectious Cryptosporidium oocysts using cell culture. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3669-3675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sulaiman, I. M., L. Xiao, and A. A. Lal. 1999. Evaluation of Cryptosporidium parvum genotyping techniques. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:4431-4435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sulaiman, I. M., L. Xiao, C. Yang, L. Escalante, A. Moore, C. B. Beard, M. J. Arrowood, and A. A. Lal. 1998. Differentiating human from animal isolates of Cryptosporidium parvum. Parasitology 120:237-244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sulaiman, I. M., U. M. Morgan, R. C. A. Thompson, A. A. Lal, and L. Xiao. 2000. Phylogenetic relationships of Cryptosporidium parasites based on the 70-kilodalton heat shock protein (HSP70) gene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:2385-2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Upton, S. J. 1997. In vitro cultivation, p. 181-201. In R. Fayer (ed.), Cryptosporidium and cryptosporidiosis. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Fla.

- 29.Upton, S. J., M. Tilley, and D. B. Brillhart. 1994. Comparative development of Cryptosporidium parvum (Apicomplexa) in 11 continuous host cell lines. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 118:233-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Upton, S. J., M. Tilley, M. V. Nesterenko, and D. B. Brillhart. 1994. A simple and reliable method of producing in-vitro infections of Cryptosporidium parvum (Apicomplexa). FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 118:45-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 1989. National primary drinking water regulations; filtration and disinfection; turbidity; Giardia lamblia, viruses, Legionella, and heterotrophic bacteria. Fed. Regist. 54:27486-27541. [Google Scholar]

- 32.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 1999. Method 1622: Cryptosporidium in water by filtration/IMS/FA. Publication EPA-821-R-99-001. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Water, Washington, D.C.

- 33.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 1999. Method 1623: Cryptosporidium and Giardia in water by filtration/IMS/FA. Publication EPA-821-R-99-006. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Water, Washington, D.C.

- 34.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 2000. Stage 2 Microbial and Disinfection Byproduct Federal Advisory Committee agreement in principle. Fed. Regist. 65:83015-83024. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wiedenmann, A., P. Kruger, and K. Botzenhart. 1998. PCR detection of Cryptosporidium parvum in environmental samples—a review of published protocols and current developments. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 21:150-166. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Woods, K. M., M. V. Nesterenko, and S. J. Upton. 1995. Development of a microtitre ELISA to quantify development of Cryptosporidium parvum in vitro. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 128:89-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]